Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Region of Southern Denmark

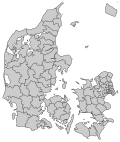

View on WikipediaThe Region of Southern Denmark[5] (Danish: Region Syddanmark, pronounced [ʁekiˈoˀn ˈsyðˌtænmɑk]; German: Region Süddänemark, pronounced [ʁeˈɡi̯oːn zyːtˈdɛːnəˌmaʁk]; North Frisian: Regiuun Syddanmark) is an administrative region of Denmark established on Monday 1 January 2007 as part of the 2007 Danish Municipal Reform, which abolished the traditional counties ("amter") and set up five larger regions. At the same time, smaller municipalities were merged into larger units, cutting the number of municipalities from 270 (271 before 2006) before 1 January 2007 to 98. The reform diminished the power of the regional level dramatically in favor of the local level and the central government in Copenhagen. The Region of Southern Denmark has 22 municipalities. The reform was implemented in Denmark on 1 January 2007, although the merger of the Funish municipalities of Ærøskøbing and Marstal, being a part of the reform, was given the go-ahead to be implemented on Sunday 1 January 2006, one year before the main reform. It borders Schleswig-Holstein (Germany) to the south and Central Denmark Region to the north and is connected to Region Zealand via the Great Belt Fixed Link.

Key Information

The regional capital is Vejle but Odense is the region's largest city and home to the main campus of the University of Southern Denmark with branch campuses in Esbjerg, Kolding and Sønderborg. The responsibilities of the regional administration include hospitals and regional public transport, which is divided between two operators, Sydtrafik on the mainland and Als, and Fynbus on Funen and adjacent islands. On the island municipalities of Ærø (since 2016)[6][7] and Fanø (since 2018),[8][9] the municipalities themselves are responsible for public transport. Billund Airport is region's main airport, it is the second-busiest airport in Denmark behind Copenhagen Airport and one of the busiest air cargo centres. It handes an average of more than three million passengers a year, and millions of pounds of cargo.

Geography

[edit]The Region of Southern Denmark is the westernmost of the Danish administrative regions (Region Zealand being the southernmost).

It consists of the former counties of Funen, Ribe and South Jutland, adding ten municipalities from the former Vejle County. The territories formerly belonging to Vejle County consist of the new municipalities of Fredericia (unchanged by the reform), Vejle (a merger of Vejle, Børkop, parts of Egtved, Give, and Jelling) and Kolding (a merger of Kolding, parts of Lunderskov, Vamdrup, and parts of both Egtved and Christiansfeld - the latter from South Jutland County). A total of 78 municipalities were combined to a total of 22 new entities.

Municipalities

[edit]

The region is subdivided into 22 municipalities:

GDP

[edit]The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 57.3 billion € in 2018, accounting for 19.0% of Denmark's economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 35,100 € or 116% of the EU27 average in the same year.[10]

North Schleswig Germans

[edit]The Region of Southern Denmark is home to the only officially recognised ethno-linguistic minority of Denmark proper, the North Schleswig Germans of North Schleswig. This minority makes up about 6% of the total population of the municipalities of Aabenraa/Apenrade, Haderslev/Hadersleben, Sønderborg/Sonderburg and Tønder/Tondern. In these four municipalities, the German minority enjoys certain linguistic rights in accordance with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[11]

Regional Council

[edit]The five regions of Denmark each have a regional council of 41 members. These are elected every four years, during the local elections.

| Election | Party | Total seats |

Elected chairman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | F | I | O | V | Ø | ... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2005 | 14 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 41 | Carl Holst (V) (1 January 2007 – 22 June 2015) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2009 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2017 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 14 | 2 | Stephanie Lose (V)(22 June 2015 – 14 March 2023;31 July – 27 November 2023) Bo Libergren (V)(14 March – 31 July 2023; 27 November 2023 – ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2021 | 12 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 17 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current | 11 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 17 | 2 | ... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Data from Kmdvalg.dk | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Carl Holst was a member of the central government of Denmark from 28 June 2015 – 30 September 2015. From 2023 Stephanie Lose became a part of the central government of Denmark.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ FOLK1: Population 1 October database from Statistics Denmark

- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". www.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Denmark Country Codes". codesofcountry.com. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 2018-09-13.

- ^ "The Region of Southern Denmark". regionsyddanmark.dk. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ^ Dalgaard Nielsen, Kirstine (8 January 2016). "Nu kører Ærø selv bussen". Fyns Amts Avis (in Danish). Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Jørgensen, Sune (7 November 2017). "Langeland vil fyre Fynbus og gøre busserne gratis". TV 2/Fyn (in Danish). Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ "Kollektiv Trafik - Bus 2018". fanoe.dk (in Danish). Fanø Municipality. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ Bjerre-Christensen, Heidi (28 April 2017). "Skilsmisse mellem Fanø og Sydtrafik en realitet". JydskeVestkysten (in Danish). Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- ^ "Germans of South Jutland in Denmark".

External links

[edit]Region of Southern Denmark

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Geography and Municipalities

The Region of Southern Denmark covers an area of 12,256 km² and geographically extends from approximately 40 km northwest of Vejle to Padborg in the south, and from Esbjerg in the west to Nyborg and surrounding islands in the east.[1] It encompasses the southern part of the Jutland peninsula, the island of Funen (Denmark's third-largest island), and smaller islands in the Little Belt and Baltic Sea regions, such as Ærø, Langeland, Tåsinge, and Lyø. The landscape consists primarily of low-lying plains and gentle hills, with Jutland's southern terrain featuring glacial moraines, sandy soils, heathlands, and dunes along the North Sea coast, while Funen exhibits more varied topography including rolling hills up to 175 m at Søhøjlandet and forested areas covering about 15% of the island.[4][5] Coastal features dominate, with over 1,000 km of shoreline including tidal flats of the Wadden Sea in the southwest (a UNESCO site spanning Denmark, Germany, and Netherlands, valued for its ecological role in bird migration and marine habitats), fjords like Odense Fjord, and sandy beaches supporting tourism and fisheries. Inland, rivers such as the Vejle River and Kongeå form valleys conducive to agriculture, with the region's fertile soils enabling dairy production and crop cultivation across 60% arable land. Elevations remain modest, averaging under 50 m above sea level, reflecting Denmark's post-glacial formation with minimal mountainous relief.[6][7] The region is subdivided into 22 municipalities, established under the 2007 administrative reform, which merged smaller units for efficiency in local governance and service delivery.[8] These range from densely populated urban centers to rural island communes, with Odense Municipality (population 196,000 as of recent estimates) serving as the largest and economic hub, and Fanø Municipality (3,300 residents) the smallest, known for its dune landscapes and ferry-dependent isolation.[1] Key municipalities include Esbjerg (major port and offshore energy base), Vejle (inland transport node), Kolding (historical trade center), and Svendborg (maritime gateway on Funen), collectively managing local infrastructure, education, and welfare under regional oversight. The full list comprises Aabenraa, Ærø, Assens, Billund, Esbjerg, Faaborg-Midtfyn, Fanø, Fredericia, Haderslev, Kerteminde, Kolding, Langeland, Middelfart, Nyborg, Nordfyn, Odense, Sønderborg, Svendborg, Tønder, Vejle, and additional units reflecting post-reform consolidations in former counties of Funen, Ribe, South Jutland, and parts of Vejle.[9][8]Climate, Environment, and Natural Resources

The Region of Southern Denmark exhibits a temperate maritime climate moderated by the North Atlantic Drift, resulting in mild, wet conditions year-round with limited temperature extremes. Average annual temperatures hover around 8–9°C, with winter lows in January and February typically 1–2°C and summer highs in July and August reaching 17–18°C; coastal areas in the west experience slightly higher precipitation due to prevailing westerly winds, averaging 750–800 mm annually, often in frequent light showers rather than heavy downpours.[10][11] These patterns align with Denmark's broader climatology, though the region's southern exposure to the Baltic Sea contributes marginally warmer summers in insular areas like Funen compared to the national average.[12] Environmentally, the region encompasses varied habitats shaped by glacial history, including sandy coasts, heathlands, and estuarine wetlands, with approximately 10% of Denmark's land under national protection, including Natura 2000 sites covering about 9% of terrestrial area for biodiversity conservation. The Wadden Sea National Park, designated in 2008 and spanning the southwest Jutland coast, protects over 1,000 km² of intertidal zones as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site recognized for its undisturbed natural processes and role as a critical stopover for millions of migratory birds, seals, and marine invertebrates.[13][14][15] This park, the largest in continental Denmark, highlights the region's ecological significance amid pressures from agriculture and sea-level rise, with ongoing management emphasizing habitat restoration over expansive development.[16] Natural resources center on agriculture, leveraging fertile post-glacial soils across roughly 60% of Denmark's land classified as cropland, with the Region of Southern Denmark producing key outputs in cereals (barley and wheat), root vegetables, and livestock such as dairy cattle and pigs, supported by intensive farming practices that account for a substantial share of national exports.[17] Coastal fisheries exploit North Sea stocks, particularly shellfish and flatfish in the Wadden Sea, though regulated to sustain populations amid EU quotas. Renewable energy resources, driven by consistent coastal winds averaging 7–9 m/s, underpin offshore wind installations like Vesterhav Nord (180 MW, operational since 2009) and Vesterhav Syd (90 MW), which contribute to the region's role in Denmark's 50%+ wind-derived electricity generation as of 2023.[18][19] These assets reflect a resource base oriented toward sustainable extraction rather than extractive minerals, with policy prioritizing integration of farming and renewables to mitigate environmental degradation.[20]History

Early and Medieval History

The region exhibits evidence of continuous human settlement from the Mesolithic era, with archaeological sites indicating hunter-gatherer communities exploiting coastal resources in southern Jutland and Funen as early as 8000 BCE, transitioning to Neolithic farming communities by approximately 4000 BCE that constructed megalithic tombs and passage graves across Jutland.[21] Iron Age settlements from around 500 BCE featured fortified villages and trade networks, particularly in southern Jutland, where Germanic tribes including Angles, Jutes, and Saxons predominated, engaging in migrations such as the Jutish movements to Britain in the 5th century CE amid the collapse of Roman influence in northern Europe.[22] The advent of the Viking Age, beginning around 725 CE with the establishment of Ribe as a proto-urban trading hub in southern Jutland, marked intensified maritime activity, commerce with Frisian and Frankish merchants, and shipbuilding innovations that facilitated raids and expeditions across the North Sea.[23] By the 9th century, the area formed the core of emerging Danish polities, with power centers like those near Jelling in south Jutland supporting chieftains who coordinated fleets for ventures into England, Francia, and the Baltic, while local economies relied on agriculture, animal husbandry, and amber trade.[24] Christianization accelerated under King Harald Bluetooth (r. c. 958–986 CE), who around 965 CE proclaimed the conversion of the Danes and unification of the realm on the larger Jelling Stone in south Jutland, building on prior missionary efforts from Christian neighbors in southern Jutland and Holstein; this shift introduced stone churches, such as those at Jelling, and suppressed pagan practices like ship burials by the late 10th century.[25] [26] In the early medieval period (c. 1000–1250 CE), the region saw consolidation under Danish kings, with assembly sites (things) in south Jutland serving as political hubs for aristocratic families managing estates and fortifications, as evidenced by excavations at sites like Nonnebakken on Funen, which reveal ring fortresses akin to Trelleborg used for royal control.[27] Southern Jutland's border dynamics with the Holy Roman Empire fostered hybrid cultural influences, culminating in the formalization of the Duchy of Schleswig by the 1230s as a semi-autonomous entity under Danish overlordship, while Funen developed ecclesiastical centers like Odense, tied to Saint Canute's martyrdom in 1086 CE, promoting pilgrimage and monastic foundations.[28]19th-20th Century Border Conflicts and Integration

The Schleswig-Holstein Question emerged in the mid-19th century from the intertwined status of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, where Schleswig was a Danish fief with a mixed Danish-German population, while Holstein was oriented toward German principalities and part of the German Confederation.[29] Tensions escalated in 1848 amid liberal revolutions across Europe, leading to an uprising in the duchies demanding separation from Denmark; this sparked the First Schleswig War (1848–1851), in which Danish forces, supported by a national-liberal movement, repelled Prussian-led German Confederation troops, culminating in an armistice on July 10, 1850, and the London Protocol of 1852, which reaffirmed Schleswig's indivisibility from Denmark while preserving Holstein's autonomy.[29] However, Danish King Christian IX's November Constitution of 1863, which extended Danish laws to Schleswig and violated prior agreements by separating it from Holstein, provoked German backlash.[30] This triggered the Second Schleswig War (1864), as Prussia and Austria, invoking treaty rights, invaded Schleswig on February 1, 1864, overwhelming Danish defenses through superior numbers—approximately 60,000 Prussian-Austrian troops against Denmark's 40,000—and strategic maneuvers like the capture of Düppel fortress in April.[31] Denmark capitulated on October 30, 1864, via the Treaty of Vienna, ceding both duchies to Prussian-Austrian condominium, which Prussia soon consolidated by annexing them outright in 1866 after defeating Austria.[30] The duchies remained under German administration through the German Empire's formation in 1871, with policies favoring Germanization, including suppression of Danish-language schools and cultural institutions in northern Schleswig (Sønderjylland), where ethnic Danes comprised a majority north of the Flensburg Fjord based on linguistic surveys.[32] World War I's outcome shifted the dynamics, as the Treaty of Versailles (June 28, 1919) mandated plebiscites in northern Schleswig to determine its fate, dividing the territory into three zones to reflect ethnic distributions without prior expulsions.[33] The first plebiscite on February 10, 1920, in the northern zone (encompassing Tønder, Haderslev, and Aabenraa areas, with 163,635 voters) resulted in 74.9% favoring reunion with Denmark, driven by Danish-majority rural and coastal communities.[32] The second on March 14, 1920, in the central zone around Flensburg (with 79,099 voters) yielded 51,000 votes (about 65%) for Germany, reflecting its urban German population, while a third southern zone was tacitly awarded to Germany without voting due to clear majorities there.[32] Consequently, the northern territory—approximately 3,938 square kilometers with 150,000 residents—was transferred to Denmark effective July 1, 1920, establishing the current border along the 1920 line, with Flensburg remaining German.[34] Integration of the reclaimed Sønderjylland proceeded methodically to balance reunification with minority protections, avoiding mass displacements despite wartime resentments. Danish administration was introduced starting April 1920, with troops entering on May 5, Danish krone currency on May 20, and full civil governance by July 10, followed by elections to local councils.[34] A 1922 language law designated Danish as the official language but permitted German minority schools (serving about 25,000 ethnic Germans, roughly 15% of the population), churches, and associations, reflecting pragmatic recognition of binational demographics to prevent irredentism.[35] Economic recovery emphasized agriculture and light industry, with Danish investment in infrastructure like roads and railways to foster loyalty, though cultural "re-Danishization" campaigns promoted Danish education and media, reducing German speakers from 25% in 1925 to under 10% by 1950 through voluntary assimilation and emigration.[36] Border stability endured through the interwar period and World War II occupation, solidified by the 1955 Bonn-Copenhagen Declarations affirming minority rights and mutual non-aggression, which quelled lingering revanchist sentiments on both sides.[35]Post-2007 Administrative Reforms

The Danish structural reform of 2007, effective from January 1, 2007, marked the most significant administrative reconfiguration in the region's modern history, abolishing the prior county system and establishing the current regional framework.[37] This nationwide initiative reduced the number of administrative counties from 14 to five regions, with the Region of Southern Denmark (Syddanmark) created through the amalgamation of three former counties: Funen County (Fyns Amt), Ribe County (Ribe Amt), and South Jutland County (Sønderjyllands Amt).[38] The reform aimed to foster larger, more efficient governance units capable of handling specialized tasks, particularly by concentrating regional responsibilities on healthcare provision, which constitutes approximately 86% of regional budgets.[39] Concurrently, the reform streamlined municipal governance by merging 271 municipalities into 98, yielding 22 municipalities within the Region of Southern Denmark to enhance local service delivery in areas such as social welfare, primary education, and elderly care.[40] Regions, including Southern Denmark, were stripped of tax-raising powers and direct democratic elections for councils were replaced with indirect selection by municipal councils, reflecting a centralization of fiscal control at the national level while delegating operational autonomy to municipalities.[41] Funding for regions derives from state block grants and municipal contributions via an equalization scheme, designed to equalize service capacities across varying local economic bases.[39] Implementation involved transitional preparations from 2005 onward, including legislative passage in June 2005 under the Liberal-Conservative coalition government, with evaluations post-2007 confirming improved economies of scale in healthcare but highlighting challenges in regional-municipal coordination.[39] Since the reform's enactment, no major structural overhauls have occurred; the regional boundaries and municipal count have persisted, underscoring the reform's enduring design amid periodic discussions of further efficiencies without substantive changes.[42] Minor adjustments, such as localized municipal boundary tweaks, have been addressed through ad hoc agreements rather than systemic redesign.[40] ![Municipalities of Region of Southern Denmark][center] The reform's legacy includes a shift toward centralized oversight of hospitals and specialized treatments, with the region overseeing five regional hospitals and aligning with national standards for patient access and resource allocation.[41] This structure has supported sustained investment in infrastructure, though critiques from local stakeholders have noted reduced regional influence over broader development policies compared to the pre-2007 county era.[39]Demographics

Population Trends and Urban Centers

The population of the Region of Southern Denmark reached 1,223,000 inhabitants as of 2020, marking a 1.5% increase from 2015, driven primarily by net positive migration and a slight excess of births over deaths.[43] By 2024, this figure had risen to 1,238,406, reflecting continued but subdued annual growth of roughly 0.3% in the intervening period.[44] These trends align with broader Danish patterns of demographic stagnation in peripheral regions, where fertility rates below replacement level—around 1.5 children per woman nationally—and an aging population structure contribute to slower expansion compared to the Copenhagen area.[45] Projections from Statistics Denmark indicate potential stabilization or marginal increases through 2040, contingent on sustained immigration inflows, as domestic out-migration to employment hubs in eastern Denmark persists.[46] Rural municipalities within the region have experienced relative depopulation, exacerbating urban-rural divides, while coastal and island areas benefit from tourism-related settlement. Overall, the region's share of Denmark's total population hovers near 20-21%, underscoring its secondary role in national demographic dynamics.[47] Key urban centers anchor the region's economic and cultural activity. Odense, the largest city and located on the island of Funen, serves as the regional hub with an urban population of approximately 180,863 residents, functioning as a center for education, manufacturing, and services.[48] Esbjerg, a major port city in western Jutland, supports around 72,000 inhabitants and drives fisheries, offshore energy, and logistics.[49] Other significant centers include Vejle (urban population circa 62,000), focused on trade and transport, and Kolding (about 61,000), known for textiles and retail. These cities collectively house over half the region's population, with Odense alone accounting for nearly 15%.[49]| Urban Center | Approximate Population (Recent Estimate) | Key Role |

|---|---|---|

| Odense | 180,863 [48] | Administrative, educational, industrial hub |

| Esbjerg | 72,000 [49] | Port, energy, fisheries |

| Vejle | 62,000 [49] | Trade, transport |

| Kolding | 61,000 [49] | Manufacturing, retail |