Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tanager

View on Wikipedia

| Tanagers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Superfamily: | Emberizoidea |

| Family: | Thraupidae Cabanis, 1847 |

| Type genus | |

| Thraupis Boie, F., 1826

| |

| Genera | |

|

Many: see text | |

| |

The tanagers (singular /ˈtænədʒər/) comprise the bird family Thraupidae, in the order Passeriformes. The family has a Neotropical distribution and is the second-largest family of birds. It represents about 4% of all avian species and 12% of the Neotropical birds.[1]

Traditionally, the family contained around 240 species of mostly brightly colored fruit-eating birds.[2] As more of these birds were studied using modern molecular techniques, it became apparent that the traditional families were not monophyletic. Euphonia and Chlorophonia, which were once considered part of the tanager family, are now treated as members of the Fringillidae, in their own subfamily (Euphoniinae). Likewise, the genera Piranga (which includes the scarlet tanager, summer tanager, and western tanager), Chlorothraupis, and Habia appear to be members of the family Cardinalidae,[3] and have been reassigned to that family by the American Ornithological Society.[4]

Description

[edit]Tanagers are small to medium-sized birds. The shortest-bodied species, the white-eared conebill, is 9 cm (4 in) long and weighs 6 g (0.2 oz), barely smaller than the short-billed honeycreeper. The longest, the magpie tanager is 28 cm (11 in) and weighs 76 g (2.7 oz). The heaviest is the white-capped tanager, which weighs 114 g (4.02 oz) and measures about 24 cm (9.4 in). Both sexes are usually the same size and weight.

Tanagers are often brightly colored, but some species are black and white. Males are typically more brightly colored than females and juveniles. Most tanagers have short, rounded wings. The shape of the bill seems to be linked to the species' foraging habits.

Distribution

[edit]Tanagers are restricted to the Western Hemisphere and mainly to the tropics. About 60% of tanagers live in South America, and 30% of these species live in the Andes. Most species are endemic to a relatively small area.

Behavior

[edit]Most tanagers live in pairs or in small groups of three to five individuals. These groups may consist simply of parents and their offspring. These birds may also be seen in single-species or mixed flocks. Many tanagers are thought to have dull songs, though some are elaborate.[citation needed]

Diet

[edit]Tanagers are omnivorous, and their diets vary by genus. They have been seen eating fruits, seeds, nectar, flower parts, and insects. Many pick insects off branches or from holes in the wood. Other species look for insects on the undersides of leaves. Yet others wait on branches until they see a flying insect and catch it in the air. Many of these particular species inhabit the same areas, but these specializations alleviate competition.

Breeding

[edit]The breeding season is March through June in temperate areas and in September through October in South America. Some species are territorial, while others build their nests closer together. Little information is available on tanager breeding behavior. Males show off their brightest feathers to potential mates and rival males. Some species' courtship rituals involve bowing and tail lifting.

Most tanagers build cup nests on branches in trees. Some nests are almost globular. Entrances are usually built on the side of the nest. The nests can be shallow or deep. The species of the tree in which they choose to build their nests and the nests' positions vary among genera. Most species nest in an area hidden by very dense vegetation. No information is yet known regarding the nests of some species.

The clutch size is three to five eggs. The female incubates the eggs and builds the nest, but the male may feed the female while she incubates. Both sexes feed the young. Five species have helpers assist in feeding the young. These helpers are thought to be the previous year's nestlings.

Taxonomy

[edit]The family Thraupidae was introduced (as the subfamily Thraupinae) in 1847 by German ornithologist Jean Cabanis. The type genus is Thraupis.[5][6]

The family Thraupidae is a member of an assemblage of over 800 birds known as the New World, nine-primaried oscines. The traditional pre-molecular classification was largely based on the different feeding specializations. Nectar-feeders were placed in Coerebidae (honeycreepers), large-billed seed-eaters in Cardinalidae (cardinals and grosbeaks), smaller-billed seed-eaters in Emberizidae (New World finches and sparrows), ground-foraging insect-eaters in Icteridae (blackbirds) and fruit-eaters in Thraupidae.[1] This classification was known to be problematic as analyses using other morphological characteristics often produced conflicting phylogenies.[7] Beginning in the last decade of the 20th century, a series of molecular phylogenetic studies led to a complete reorganization of the traditional families. Thraupidae now includes large-billed seed eaters, thin-billed nectar feeders, and foliage gleaners as well as fruit-eaters.[1]

One consequence of redefining the family boundaries is that for many species their common names are no longer congruent with the families in which they are placed. As of July 2020 there are 39 species with "tanager" in the common name that are not placed in Thraupidae. These include the widely distributed scarlet tanager and western tanager, which are both now placed in Cardinalidae. There are also 106 species within Thraupidae that have "finch" in their common name.[8]

A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2014 revealed that many of the traditional genera were not monophyletic.[1] In the resulting reorganization six new genera were introduced, eleven genera were resurrected, and seven genera were abandoned.[9][8]

As of March 2025 the family contains 393 species which are divided into 15 subfamilies and 105 genera.[1][8] For a complete list, see the article List of tanager species.

List of genera

[edit]Catamblyrhynchinae

[edit]The plushcap has no close relatives and is now placed in its own subfamily. It was previously placed either in the subfamily Catamblyrhynchinae within the Emberizidae or in its own family Catamblyrhynchidae.[1]

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Catamblyrhynchus Lafresnaye, 1842 |

|

Charitospizinae

[edit]The coal-crested finch is endemic to the grasslands of Brazil and has no close relatives. It is unusual in that both sexes have a crest. It was formerly placed in Emberizidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Charitospiza Oberholser, 1905 |

|

Orchesticinae

[edit]Two species with large thick bills. Parkerthraustes was formerly placed in Cardinalidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Orchesticus Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Parkerthraustes Remsen, 1997 |

|

Nemosiinae

[edit]Brightly colored, sexually dichromatic birds. Most form single-species flocks.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Nemosia Vieillot, 1816 |

|

|

Cyanicterus Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

|

Sericossypha Lesson, 1844 |

|

|

Compsothraupis Richmond, 1915 |

|

Emberizoidinae

[edit]Grassland dwelling birds that were formerly placed in Emberizidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Coryphaspiza G.R. Gray, 1840 |

|

|

Embernagra Lesson, 1831 |

|

|

Emberizoides Temminck, 1822 |

|

Porphyrospizinae

[edit]Yellow billed birds. The blue finch (Rhopospina caerulescens) was formerly placed in Cardinalidae; the other species were formerly placed in Emberizidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Incaspiza Ridgway, 1898 |

|

|

Rhopospina Cabanis, 1851 |

|

Hemithraupinae

[edit]These species are sexually dichromatic and many have yellow and black plumage. Except for Heterospingus, they have slender bills.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Chlorophanes Reichenbach, 1853 |

|

|

Iridophanes Ridgway, 1901 |

|

|

Chrysothlypis Berlepsch, 1912 |

|

|

Heterospingus Ridgway, 1898 |

|

|

Hemithraupis Cabanis, 1850 |

|

Dacninae

[edit]Sexually dichromatic species—males have blue plumage and females are green.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Tersina Vieillot, 1819 |

|

|

Cyanerpes Oberholser, 1899 |

|

|

Dacnis Cuvier, 1816 |

|

Saltatorinae

[edit]Mainly arboreal with long tails and thick bills. Formerly placed in Cardinalidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Saltatricula Burmeister, 1861 |

|

|

Saltator Vieillot, 1816 |

|

Coerebinae

[edit]

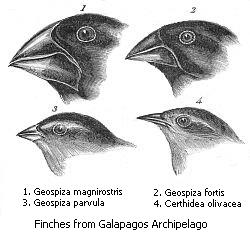

This subfamily includes Darwin's finches, of which all but the Cocos finch are endemic to the Galápagos Islands. Most Coerebinae species were formerly placed in Emberizidae; the exceptions are the bananaquit that was placed in Parulidae and the orangequit that was placed in Thraupidae. These species build domed or covered nests with side entrances. They have evolved a variety of foraging techniques, including nectar-feeding (Coereba, Euneornis), seed-eating (Geospiza, Loxigilla, Tiaris), and insect gleaning (Certhidea).[1]

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Coereba Vieillot, 1809 |

|

|

Tiaris Swainson, 1827 |

|

|

Euneornis Fitzinger, 1856 |

|

|

Melopyrrha Bonaparte, 1853 |

|

|

Loxipasser Bryant, 1866 |

|

|

Phonipara Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

|

Loxigilla Lesson, 1831 |

|

|

Melanospiza Ridgway, 1897 |

|

|

Asemospiza Burns, Unitt, & Mason, 2016 |

|

| Darwin's finches: | ||

|

Certhidea Gould, 1837 |

|

|

Platyspiza Ridgway, 1897 |

|

|

Pinaroloxias Sharpe, 1885 |

|

|

Camarhynchus Gould, 1837 |

|

|

Geospiza Gould, 1837 |

|

Tachyphoninae

[edit]Most of these are lowland species. Many have ornamental features such as crests, and many have sexually dichromatic plumage.[1]

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Volatinia Reichenbach, 1850 |

|

|

Conothraupis Sclater, PL, 1880 |

|

|

Creurgops Sclater, PL, 1858 |

|

|

Eucometis Sclater, PL, 1856 |

|

|

Trichothraupis Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Heliothraupis Lane et al., 2021 |

|

|

Loriotus Jarocki, 1821 |

|

|

Coryphospingus Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Tachyphonus Vieillot, 1816 |

|

|

Rhodospingus Sharpe, 1888 |

|

|

Lanio Vieillot, 1816 |

|

|

Ramphocelus Desmarest, 1805 |

|

Sporophilinae

[edit]These species were formerly placed in Emberizidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Sporophila Cabanis, 1844 |

Seedeaters and seed finches (includes species previously assigned to Dolospingus and Oryzoborus) 41 species:

|

Poospizinae

[edit]Some of these species were formerly placed in Emberizidae.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Piezorina Lafresnaye, 1843 |

|

|

Xenospingus Cabanis, 1867 |

|

|

Cnemoscopus Bangs & Penard, 1919 |

|

|

Pseudospingus Berlepsch & Stolzmann, 1896 |

|

|

Poospiza Cabanis, 1847 |

|

|

Kleinothraupis Burns, Unitt, & Mason, 2016 |

|

|

Sphenopsis Sclater, 1862 |

|

|

Thlypopsis Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Castanozoster Burns, Unitt, & Mason, 2016 |

|

|

Donacospiza Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Cypsnagra Lesson, R, 1831 |

|

|

Poospizopsis Berlepsch, 1893 |

|

|

Urothraupis Taczanowski & Berlepsch, 1885 |

|

|

Nephelornis Lowery & Tallman, 1976 |

|

|

Microspingus Taczanowski, 1874 |

|

Diglossinae

[edit]This is a morphologically diverse group that includes seed-eaters (Nesospiza, Sicalis, Catamenia, Haplospiza), arthropod feeders (Conirostrum), a bamboo specialist (Acanthidops), an aphid feeder (Xenodacnis), and boulder field specialists (Idiopsar). Many species live at high altitudes. Conirostrum was previously placed in Parulidae, Diglossa was placed in Thraupidae, and the remaining genera were placed in Emberizidae.[1]

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Conirostrum d'Orbigny & Lafresnaye, 1838 |

|

|

Sicalis F. Boie, 1828 |

13 species

|

|

Phrygilus Cabanis, 1844 |

|

|

Nesospiza Cabanis, 1873 |

|

|

Rowettia Lowe, 1923 |

|

|

Melanodera Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

|

Geospizopsis Bonaparte, 1856 |

|

|

Haplospiza Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Acanthidops Ridgway, 1882 |

|

|

Xenodacnis Cabanis, 1873 |

|

|

Idiopsar Cassin, 1867 |

|

|

Catamenia Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

|

Diglossa Wagler, 1832 |

18 species

|

Thraupinae

[edit]Typical tanagers.

| Image | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|

|

Calochaetes Sclater, PL, 1879 |

|

|

Iridosornis Lesson, 1844 |

|

|

Rauenia Wolters, 1980 |

|

|

Pipraeidea Swainson, 1827 |

|

|

Pseudosaltator K.J. Burns, Unitt & N.A. Mason, 2016 |

|

|

Dubusia Bonaparte, 1850 |

|

|

Buthraupis Cabanis, 1851 |

|

|

Sporathraupis Ridgway, 1898 |

|

|

Tephrophilus R. T. Moore, 1934 |

|

|

Chlorornis Reichenbach, 1850 |

|

|

Cnemathraupis Penard, 1919 |

|

|

Anisognathus Reichenbach, 1850 |

|

|

Chlorochrysa Bonaparte, 1851 |

|

|

Wetmorethraupis Lowery & O'Neill, 1964 |

|

|

Bangsia Penard, 1919 |

|

|

Lophospingus Cabanis, 1878 |

|

|

Neothraupis Hellmayr, 1936 |

|

|

Diuca Reichenbach, 1850 |

|

|

Gubernatrix Lesson, 1837 |

|

|

Stephanophorus Strickland, 1841 |

|

|

Cissopis Vieillot, 1816 |

|

|

Schistochlamys Reichenbach, 1850 |

|

|

Paroaria Bonaparte, 1832 |

|

|

Ixothraupis Bonaparte, 1851 |

|

|

Chalcothraupis Bonaparte, 1851 |

|

|

Poecilostreptus Burns, KJ, Unitt, & Mason, NA, 2016 |

|

|

Thraupis F. Boie, 1826 |

|

|

Stilpnia Burns, KJ, Unitt, & Mason, NA, 2016 |

15 species

|

|

Tangara Brisson, 1760 |

28 species

|

Genera formerly placed in Thraupidae

[edit]Passerellidae – New World sparrows[10]

- Chlorospingus – eight species - bush-tanagers

- Oreothraupis – tanager finch

Cardinalidae – cardinals[11][7]

- Piranga – 9 species - northern tanagers

- Habia – five species - ant-tanagers or habias

- Chlorothraupis – three species

- Amaurospiza – four species

Fringillidae – subfamily Euphoniinae

- Euphonia – 27 species

- Chlorophonia – five species

Phaenicophilidae – Hispaniolan tanagers[10][12]

- Microligea – green-tailed warbler

- Xenoligea – white-winged warbler

- Phaenicophilus – two species

Mitrospingidae – Mitrospingid tanagers[10]

- Mitrospingus – two species

- Orthogonys – olive-green tanager

- Lamprospiza – red-billed pied tanager

- Nesospingus – Puerto Rican tanager[10][12]

- Calyptophilus – two species - chat-tanagers[10][12]

- Rhodinocichla – rosy thrush-tanager[10][12]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Burns, K.J.; Shultz, A.J.; Title, P.O.; Mason, N.A.; Barker, F.K.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2014). "Phylogenetics and diversification of tanagers (Passeriformes: Thraupidae), the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 75: 41–77. Bibcode:2014MolPE..75...41B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.02.006. PMID 24583021.

- ^ Storer, Robert W. (1970). "Subfamily Thraupinae". In Paynter, Raymond A. Jr (ed.). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 13. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. pp. 246–408.

- ^ Yuri, T.; Mindell, D. P. (May 2002). "Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Fringillidae, "New World nine-primaried oscines" (Aves: Passeriformes)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 23 (2): 229–243. Bibcode:2002MolPE..23..229Y. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00012-X. PMID 12069553.

- ^ "Family: Cardinalidae". American Ornithological Society. Retrieved Feb 1, 2019.

- ^ Cabanis, Jean (1847). "Ornithologische Notizen". Archiv für Naturgeschichte (in German). 13: 186–256, 308–352 [316].

- ^ Melville, R.V. (1977). "Opinion 1069 Correction of entry in official list of family-group names in zoology for name number 428 (Thraupidae)". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 33 (3/4): 162–164.

- ^ a b Klicka, J.; Burns, K.; Spellman, G. M. (2007). "Defining a monophyletic Cardinalini: A molecular perspective". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (3): 1014–1032. Bibcode:2007MolPE..45.1014K. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.07.006. PMID 17920298.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (February 2025). "Tanagers and allies". IOC World Bird List Version 15.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 23 March 2025.

- ^ Burns, K.J.; Unitt, P.; Mason, N.A. (2016). "A genus-level classification of the family Thraupidae (Class Aves: Order Passeriformes)". Zootaxa. 4088 (3): 329–354. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4088.3.2. PMID 27394344.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2013). "Going to extremes: contrasting rates of diversification in a recent radiation of New World passerine birds". Systematic Biology. 62 (2): 298–320. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys094. PMID 23229025.

- ^ Burns, K.J.; Hackett, S.J.; Klein, N.K. (2003). "Phylogenetic relationships of Neotropical honeycreepers and the evolution of feeding morphology". Journal of Avian Biology. 34 (4): 360–370. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2003.03171.x.

- ^ a b c d e Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Lovette, I.J. (2015). "New insights into New World biogeography: An integrated view from the phylogeny of blackbirds, cardinals, sparrows, tanagers, warblers, and allies". The Auk. 132 (2): 333–348. doi:10.1642/AUK-14-110.1.

Further reading

[edit]- Remsen, J. V. Jr. (2016). "Proposal 730: Revise generic limits in the Thraupidae". South American Classification Committee, American Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jungle-walk.com tanager pictures

- Tanager videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- . . 1914.

Tanager

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and systematics

Etymology and nomenclature

The name "tanager" originates from the Old Tupi word tangara, referring to a small, colorful bird, which was borrowed into Portuguese as tangará and entered European scientific literature in the mid-18th century.[10][11] Carl Linnaeus first applied it formally in 1766 to the scarlet tanager (Piranga olivacea), describing the species as Tanagra olivacea in the 12th edition of Systema Naturae, based on specimens from North America.[12] The genus name Piranga itself derives from Tupi tijepiranga, denoting an unidentified small bird, highlighting the influence of Indigenous Brazilian languages on ornithological nomenclature for Neotropical species.[13] The family name Thraupidae stems from the type genus Thraupis, which is based on the Ancient Greek term thraupis (θραυπίς), used by Aristotle to describe an unidentified small bird, possibly a finch-like species. This classical root was adopted in the early 19th century as ornithologists formalized passerine families, with Thraupidae established to encompass the diverse New World tanagers.[14] Nomenclature for tanagers has evolved significantly since the 19th century, reflecting advances in comparative anatomy and systematics. For instance, the genus Piranga—encompassing North American species like the scarlet tanager—was initially placed within the broad family Emberizidae (then including many finch-like birds) by early classifiers such as Georges Cuvier and William Swainson, before being segregated into Thraupidae and, more recently, transferred to Cardinalidae based on molecular and morphological evidence.[15][16] Common names within the family often evoke plumage characteristics, such as "honeycreeper" for vibrant genera like Cyanerpes, which are small tanagers in Thraupidae specialized for nectar-feeding but phylogenetically unrelated to the Old World honeyeaters of Meliphagidae.[17]Phylogenetic position

The family Thraupidae belongs to the superfamily Emberizoidea within the Passerida clade of oscine passerines, representing the second-largest family among the nine-primaried songbirds with 392 species. Phylogenetic analyses place Thraupidae as sister to Cardinalidae, with Emberizidae sister to this combined clade, a relationship supported by multi-locus molecular data encompassing nuclear and mitochondrial markers across Passeriformes. Key molecular studies have solidified the monophyly of Thraupidae and refined its internal structure. Barker et al. (2013) first delineated a monophyletic Thraupidae using genus-level sampling and six genetic loci, excluding several taxa previously included based on morphology. This was expanded in Burns et al. (2014), which provided the first comprehensive species-level phylogeny sampling 353 of 371 recognized tanager species, identifying 13 major clades and confirming Thraupidae's diversification as the largest radiation of Neotropical songbirds.[18] Recent updates have incorporated newly described species into established clades, enhancing resolution within Thraupidae. For instance, Lane et al. (2021) described Heliothraupis oneilli, a new genus and species from the Andean foothills, with phylogenetic analysis embedding it within the Ramphocelus clade alongside genera such as Coryphospingus and Tachyphonus.[19] Historical classifications of Thraupidae included several groups now recognized as distinct, reflecting advances in molecular systematics. Darwin's finches (genera Geospiza, Camarhynchus, and Certhidea), once placed in Emberizidae or as a separate subfamily within Thraupidae, are now firmly integrated into Thraupidae as the subfamily Coerebinae per the IOC World Bird List v15.1 (2025).[20] Further refinements address paraphyly in related taxa previously associated with Thraupidae. The 2024 IOC World Bird List update introduced the genus Driophlox for four ant-tanager species formerly in Habia (now in Cardinalidae), resolving paraphyly by separating them from the core Thraupidae radiation based on updated phylogenies.[21]Subfamilies and genera

The classification of the Thraupidae family into subfamilies is based on a comprehensive molecular phylogeny that identified 15 distinct clades supported by strong statistical evidence, as detailed in Burns et al. (2014).[22] This framework expanded the family to include taxa previously classified in other groups, such as certain finches and honeycreepers, totaling approximately 371 species at the time. Subsequent studies have transferred several taxa, including the genus Piranga and ant-tanagers (formerly Habia, now partly Driophlox), to the family Cardinalidae, reducing the species count. A subsequent genus-level revision by Burns et al. (2016) recognized 111 genera across these subfamilies, addressing widespread polyphyly in traditional groupings by proposing 11 new genera and reassigning species to better reflect monophyletic lineages. The current IOC World Bird List v15.1 (2025) recognizes 107 genera and 392 species, incorporating new discoveries, splits, and the aforementioned reclassifications. For instance, Lane et al. (2021) described the monotypic genus Heliothraupis for the Inti Tanager (H. oneilli), a vibrant species from the Andean foothills of southeastern Peru and western Bolivia, placing it within Thraupinae based on phylogenetic analyses. Resolutions to polyphyly have been particularly notable in former broad genera; for example, the traditional Thraupis (including the Blue-and-yellow Tanager) was split, with species reassigned to genera such as Pipraeidea, Thraupis (restricted), and others to ensure monophyly, as recommended in Burns et al. (2016). Similarly, emberizoid-like taxa were consolidated into Emberizoidinae, distinguishing them from true emberizids in Passerellidae. The subfamilies vary greatly in size and composition, from monotypic groups to large radiations encompassing diverse feeding guilds. The following table summarizes the 15 subfamilies, highlighting key genera (with representative examples where subfamilies include many) and approximate species counts derived from the 2014 phylogeny and subsequent updates adjusted for major reclassifications such as the transfer of ant-tanagers to Cardinalidae; the current total is 392 species per IOC World Bird List v15.1 (2025).[22]| Subfamily | Key Genera (Examples) | Approximate Species Count |

|---|---|---|

| Catamblyrhynchinae | Catamblyrhynchus (plushcap tanager) | 1 |

| Charitospizinae | Charitospiza (siskin-like tanager) | 1 |

| Orchesticinae | Orchesticus, Parkerthraustes (grosbeak-tanagers) | 2 |

| Nemosiinae | Nemosia, Cyanicterus, Sericossypha, Compsothraupis | 5 |

| Emberizoidinae | Emberizoides, Embernagra, Coryphaspiza (longspurs and grass-tanagers) | 6 |

| Porphyrospizinae | Porphyrospiza, Incaspiza, Phrygilus (inca finches) | 9 |

| Hemithraupinae | Hemithraupis, Heterospingus, Chlorophanes (honey-tanagers and allies) | 9 |

| Dacninae | Dacnis, Cyanerpes, Tersina (honeycreepers) | 14 |

| Saltatorinae | Saltator (including former Saltatricula; saltators and grosbeaks) | 16 |

| Coerebinae | Coereba (bananaquit), Geospiza, Certhidea (Darwin's finches and allies; 12 genera total) | 29 |

| Tachyphoninae | Tachyphonus, Ramphocelus, Eucometis (caciques and allies; 10 genera total) | 26 |

| Sporophilinae | Sporophila, Oryzoborus, Dolospingus (grass-finches and seedeaters) | 39 |

| Poospizinae | Poospiza, Hemispingus, Thlypopsis (bush-tanagers and allies; 12 genera total) | 44 |

| Diglossinae | Diglossa, Conirostrum, Sicalis (flowerpiercers, conebills, and yellow-finches; 14 genera total) | 64 |

| Thraupinae | Tangara (mountain-tanagers), Thraupis (restricted; palm-tanagers); 22 genera total, including new Heliothraupis) | 102 |

Physical description

Morphology and size

Tanagers in the family Thraupidae are small to medium-sized passerine birds, typically measuring 10 to 20 cm in length and weighing between 7 and 60 g, though extremes range from the diminutive white-eared conebill (Conirostrum leucogenys) at about 9 cm long and 7 g to the elongated magpie tanager (Cissopis leverianus) at 25–30 cm long and 69–76 g, or the heaviest white-capped tanager (Sericossypha albocristata) at around 24 cm and 114 g.[1][1] Shared morphological traits include short, rounded wings suited for maneuverability in dense forest environments and robust bills that vary widely in shape, from conical and finch-like in seed-eating species to slender and decurved in nectar-feeding members of the subfamily Dacninae.[1] Strong legs adapted for perching support their primarily arboreal lifestyle, enabling them to forage among branches and foliage.[1] Sexual dimorphism is prevalent, with males often exhibiting more vibrant plumage than females, though some species in the subfamily Thraupinae display monomorphic coloration where both sexes are similarly dull. Plumage variation, including these dimorphic patterns, is closely tied to underlying morphological structures like feather arrangement, but detailed coloration is addressed elsewhere.Plumage variation

Tanagers (family Thraupidae) exhibit remarkable plumage diversity, with males of many species displaying vibrant hues such as iridescent blues, reds, and yellows that serve as key identifiers within the family. These bright colors arise primarily from a combination of carotenoid pigments and structural coloration mechanisms in the feathers. Structural elements, including oblong feather barbs and dihedral barbules, enhance color saturation and create effects like iridescence or "super black" appearances by manipulating light through scattering and absorption; for instance, male tanagers often have wider barbs compared to females, amplifying pigment signals.[23][23] Plumage variation is pronounced between sexes and age classes, with males typically showing more saturated and contrasting colors than females, a pattern driven by differences in feather microstructures rather than pigments alone. Females often exhibit duller versions of these hues, such as pale yellows or olive tones, due to simpler cylindrical barbules that reduce brightness. Juveniles across species display cryptic brown or olive-streaked plumage, providing camouflage during early development. Some species undergo seasonal plumage shifts, where breeding males molt from bright to yellow-green non-breeding plumage in fall.[23][23] Subfamily-specific patterns further highlight tanager plumage diversity. Species in the genus Tangara, such as the speckled tanager (Ixothraupis guttata, formerly placed in Tangara), feature greenish upperparts with white underparts densely marked by black spots or chevrons, creating a speckled appearance that varies slightly by sex and age. In contrast, genera like Sporophila (seedeaters) often display stark black-and-white contrasts, as seen in the black-and-white seedeater (Sporophila luctuosa), where males have bold black crowns, wings, and tails against white underparts. The paradise tanager (Tangara paradisea) exemplifies complex patterning through its multicolored plumage—combining black, blue, green, red, and yellow patches—which may involve mimicry of other flock species to facilitate social integration in mixed groups.[24] Molting processes underpin these variations, with most tanagers undergoing a single annual pre-basic molt after breeding to replace worn feathers and acquire fresh plumage. This complete molt typically occurs in the non-breeding season, restoring bright colors for the subsequent breeding period. Some species exhibit delayed plumage maturation, where young males retain subadult plumage for one or more cycles before achieving full definitive coloration; for instance, in Sporophila seedeaters like the lined seedeater (Sporophila lineola), males attain adult plumage during their second pre-basic molt, allowing gradual development of black-and-white patterns.[25][26][27]Distribution and habitat

Geographic range

Tanagers, belonging to the family Thraupidae, are predominantly distributed across the Neotropical region, extending from northern Mexico southward to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, with the vast majority of their approximately 384 species occurring in South America.[28][29] Over 300 species are found in Central and South America combined, representing a significant portion of the region's avian diversity.[30] While the core range is Neotropical, Thraupidae species occur in North America primarily as vagrants or established introduced populations, such as the saffron finch (Sicalis flaveola) breeding in southern Florida, with no native breeding populations north of Mexico.[31] Vagrants occasionally appear outside the Americas, though records are rare. Endemism is particularly concentrated in biodiversity hotspots like the Andes, where about 30% of tanager species occur, and Colombia alone hosts more than 50 species, many restricted to montane regions such as the multicolored tanager (Chlorochrysa nitidissima) in the Western and Central Andes.[32][33] The Atlantic Forest of Brazil is another key area of endemism, supporting species like the critically endangered cherry-throated tanager (Nemosia rourei), confined to small montane patches.[34] Islands such as Trinidad feature unique subspecies forms, including those of the blue-gray tanager (Thraupis episcopus).[35] Historical distribution patterns reflect post-Pleistocene expansions, with older lineages primarily along the Andes and Brazil's coastal regions, though no widespread recent contractions have occurred beyond localized extinctions in fragmented habitats.[36]Habitat preferences

Tanagers, as a family (Thraupidae), exhibit a broad range of habitat preferences across the Neotropics, with the majority of species favoring forested environments, particularly humid tropical and subtropical forests. Predominantly, these birds occupy lowland rainforests, montane cloud forests, and associated woodland edges, where genera such as Tangara are commonly found in the upper canopy layers of dense, humid vegetation, foraging among epiphytes and fruiting trees.[37][28] Altitudinal variation is notable within the family, spanning from sea level in lowland Amazonian forests to high-elevation Andean habitats exceeding 3,000 m. For instance, species in the genus Buthraupis, such as the hooded mountain-tanager (Buthraupis montana), prefer montane cloud forests and elfin woodlands at elevations between 2,200 and 3,500 m, while others like certain Saltator species inhabit drier savannas and scrublands. A smaller subset utilizes coastal mangroves and riverine forests, including the hooded tanager (Nemosia pileata) in gallery and mangrove settings.[38][39] Microhabitat use often involves flocking in fruiting trees for frugivores or concentrating in flowering epiphyte zones for nectar-feeding species, enhancing their access to resources in stratified forest layers. Many tanager species demonstrate adaptability to disturbed environments, thriving in secondary growth, forest edges, and fragmented landscapes—exemplified by edge-tolerant genera like Thraupis in regrowth areas—yet they generally avoid highly urbanized zones, preferring semi-natural or rural settings with vegetative cover.[28]Behavior and ecology

Social behavior

Tanagers exhibit varied flocking tendencies across the family Thraupidae, with many species, particularly in the genus Tangara, commonly forming or joining mixed-species flocks that provide anti-predator benefits through increased vigilance and predator dilution. These flocks often consist of 20-50 birds in Neotropical forests, where multiple Tangara species contribute to group cohesion and foraging efficiency while reducing individual predation risk.[40][41][42] In contrast, genera like Euphonia tend toward smaller, more solitary or pair-based groups, rarely participating in large mixed flocks and instead maintaining loose associations of 4-10 individuals for localized activities.[43][44] Territoriality in tanagers is typically seasonal and pronounced during breeding, with males defending patches of habitat or leks through song and aggressive displays to secure resources and mates. In monogamous species, which comprise the majority of the family, strong pair bonds form, often persisting beyond the breeding season and involving coordinated defense of shared territories.[45][46][28] Helpers in cooperative species like the White-banded Tanager (Neothraupis fasciata) assist in territorial defense, enhancing group protection against intruders.[47] Tanagers are diurnal birds, active primarily during daylight hours for most behaviors, though some exhibit crepuscular singing at dawn and dusk to communicate territory or group cohesion. They roost communally in dense foliage at night, selecting sheltered sites in the forest canopy or understory to minimize exposure to predators.[48] Interspecific interactions among tanagers include vocal mimicry, where some species imitate the calls of other birds to facilitate group signaling or deception in mixed flocks. Occasional hybridizations occur, particularly between closely related Ramphocelus species such as the Flame-rumped Tanager (Ramphocelus flammigerus) subspecies, resulting in stable hybrid zones driven by ecological overlap and gene flow over millennia.[49][50]Diet and foraging

Tanagers (family Thraupidae) exhibit an omnivorous diet, with frugivory predominant across approximately 60% of species, supplemented by arthropods, nectar, and seeds depending on the taxon. Fruits from trees and shrubs, such as berries of Cecropia and Myrcia species, form the core of their intake, comprising up to 61% of observed foraging events in some Neotropical communities. Arthropods, including insects like beetles, caterpillars, and spiders, account for 20–70% of the diet in various genera, often obtained through active searching. Nectar consumption is less common but notable in certain subfamilies, while seeds are a primary resource for granivorous groups.[51] Foraging techniques vary by food type and microhabitat, emphasizing efficiency in diverse forest strata. For fruits, tanagers commonly glean items while perched, reach downward from branches, or hang upside down to access clusters, with hovering occasionally used to peck at distant resources. Arthropod foraging involves foliage gleaning on leaves and branches (over 65% of events in some studies), sally strikes into the air for flying insects, or probing moss and epiphytes along limbs. Ground probing occurs in seed-specialized taxa like those in Poospizinae, where individuals sift through leaf litter or grass. Some mixed-species flocks display cooperative defense of fruiting trees, with vocalizations and displays deterring competitors to maintain access. Bill morphology, such as stout conical shapes in seed-eaters or curved forms in nectar-feeders, facilitates these methods without compromising generalist capabilities.[51] Dietary composition shifts seasonally to meet nutritional demands, with increased insectivory during breeding periods to provide protein for egg production and nestling growth. Neotropical residents similarly emphasize protein-rich arthropods during reproduction, while dry periods may heighten nectar or fruit dependence for hydration and energy. These adjustments underscore the family's adaptability to fluctuating resources.[52][53] Subfamily specializations reflect evolutionary adaptations to specific resources, enhancing niche partitioning. In Coerebinae (honeycreepers, including bananaquits), species like Coereba flaveola consume up to 76% nectar using brush-tipped tongues for capillary action, though they are not true pollinators and supplement with fruits and insects from diverse flowers. Dacninae taxa, such as Dacnis and Cyanerpes, feature tubular tongues and curved bills suited for nectar extraction from tubular corollas (12–29% of diet), alongside fruits and arthropods gleaned from foliage. Sporophilinae, encompassing seedeaters like Sporophila, specialize in grass and bamboo seeds via conical bills for husking, with granivory comprising the majority of intake and minimal frugivory or insectivory. These traits highlight how dietary convergence and divergence drive Thraupidae diversity.[51]Reproduction

Tanagers primarily exhibit monogamous breeding systems, with pairs forming bonds for the duration of the breeding season and providing biparental care to offspring.[28] In some genera, such as Ramphocelus, rare instances of polygyny have been documented, where a single male mates with multiple females.[28] Clutch sizes typically range from 2 to 4 eggs, though this varies by species and region.[54] Nests are predominantly open and cup-shaped, constructed by the female from dry grass, moss, rootlets, and other plant fibers, and placed in trees or shrubs 2 to 10 meters above ground.[28] These nests are often woven into forks or supported by branches for stability.[55] Cavity nesting is uncommon within the family but occurs in certain Euphonia species, which may repurpose natural tree holes or old woodpecker cavities for domed nests with side entrances.[56] Incubation duties are handled solely by the female and last 12 to 14 days in most species. Following hatching, both parents feed the altricial nestlings, which remain in the nest for 11 to 15 days before fledging; fledglings achieve independence approximately 2 to 3 weeks later.[57] Breeding in tropical tanager populations often aligns with the rainy season, from November to March in some regions, to coincide with peaks in insect and fruit availability that support nestling growth.[58] Certain habitat-edge species face brood parasitism by cowbirds such as the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) or shiny cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis), which can reduce nesting success by laying eggs in host nests.[59]Conservation status

Major threats

Habitat loss represents the most significant threat to tanager populations worldwide, primarily driven by deforestation and agricultural expansion in their Neotropical ranges. In the Amazon basin, approximately 20% of the original forest cover has been lost since the 1980s, severely impacting endemic species in the genus Tangara, such as the paradise tanager (Tangara chilensis), which relies on contiguous forest habitats for survival.[60][61] In the Andean regions, expanding agriculture has fragmented high-elevation forests, threatening species like the masked mountain-tanager (Buthraupis cucullata) by reducing available breeding and foraging areas.[62] Climate change exacerbates these pressures through altitudinal range shifts and disruptions to ecological interactions. High-elevation tanagers, including the hooded mountain-tanager (Buthraupis montana), are experiencing habitat loss as warming temperatures force upward migrations, compressing their ranges against montane summits with limited suitable area.[63][64] Additionally, altered fruiting cycles due to changing precipitation and temperature patterns mismatch the timing of fruit availability with the frugivorous diets of many tanager species, potentially reducing reproductive success.[65] Other anthropogenic threats include illegal trapping for the pet trade, pesticide use, and invasive species competition. Colorful species like the red-legged honeycreeper (Cyanerpes cyaneus) are heavily targeted for the international pet market, leading to population declines in accessible lowland forests.[66] Pesticides applied in agricultural areas diminish insect prey populations, affecting insectivorous and omnivorous tanagers that depend on arthropods during breeding seasons.[67] On Caribbean islands, invasive birds such as the shining cowbird (Molothrus bonariensis) compete with and parasitize island-endemic tanagers, further stressing small populations.[68] According to the IUCN Red List, approximately 16% of the 384 tanager species (61 total) are threatened with extinction as of 2024, including 5 critically endangered species such as the cherry-throated tanager (Nemosia rourei), whose population is estimated at 20 or fewer mature individuals confined to fragmented Atlantic Forest remnants as of 2025.[28][69][70]Protected species and efforts

Several protected areas in the Neotropics play a crucial role in safeguarding tanager populations, particularly in biodiversity hotspots. Yasuní National Park in Ecuador encompasses over 1 million hectares of Amazonian rainforest, providing essential habitat for numerous Amazonian tanager species, including the paradise tanager (Tangara chilensis) and speckled tanager (Ixothraupis guttata), through community-led preservation efforts by indigenous groups like the Kichwa Añangu.[71][72][73] In Brazil's Atlantic Forest, reserves such as those managed under the National Action Plan for Conservation of Birds protect endemic species like the critically endangered cherry-throated tanager (Nemosia rourei) and the vulnerable black-backed tanager (Tangara peruviana), where fragmented forests are maintained to support small, isolated populations.[74][75][76] Conservation initiatives targeting tanagers emphasize international collaboration and habitat restoration. BirdLife International's Preventing Extinctions Programme has supported recovery actions for over 25 critically endangered bird species since 2000, including targeted monitoring and habitat protection for tanagers like the seven-colored tanager (Tangara fastuosa) through expanded restoration in Brazil's Atlantic Forest.[77][78][79] The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) regulates trade in vulnerable tanager genera, with species like the large-billed seed-finch (Sporophila crassirostris) listed under Appendix II to curb illegal pet trade, and ongoing proposals for additional Sporophila species such as the great-billed seed-finch (Sporophila maximiliani) discussed at CoP20 in 2025.[80][81] Reforestation projects further aid frugivorous tanagers by enhancing seed dispersal and carbon storage in regenerating tropical forests, as demonstrated in studies from Costa Rica and Panama where bird-mediated restoration increased forest recovery by up to 38%.[82][83] Notable success stories highlight the effectiveness of targeted interventions. The yellow cardinal (Gubernatrix cristata), recently reclassified within Thraupidae, has benefited from captive-breeding programs in Brazil and Uruguay, where confiscated individuals from the illegal trade have produced offspring for reintroduction and translocation efforts, including three releases in 2023 that bolster wild populations.[84][85][86] Monitoring via platforms like eBird has enabled citizen science contributions to track tanager distributions and population trends, supporting adaptive management in regions like the Atlantic Forest and Amazon.[77] Despite these advances, research gaps persist in tanager conservation. Updated phylogenetic analyses are needed to refine ex-situ breeding strategies, as current trees reveal ongoing uncertainties in evolutionary relationships within Thraupidae, potentially affecting prioritization of distinct lineages for protection.[87][88] Community-based ecotourism in hotspots, such as Audubon's Central Andes Birding Trail in Colombia, promotes sustainable income while conserving habitats for species like the multicolored tanager (Chlorochrysa nitidissima), though broader implementation is required to address funding and local engagement challenges.[89][90]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/tanager