Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Repeater

View on Wikipedia

In telecommunications, a repeater is an electronic device that receives a signal and retransmits it. Repeaters are used to extend transmissions so that the signal can cover longer distances or be received on the other side of an obstruction. Some types of repeaters broadcast an identical signal, but alter its method of transmission, for example, on another frequency or baud rate.

There are several different types of repeaters; a telephone repeater is an amplifier in a telephone line, an optical repeater is an optoelectronic circuit that amplifies the light beam in an optical fiber cable; and a radio repeater is a radio receiver and transmitter that retransmits a radio signal.

A broadcast relay station is a repeater used in broadcast radio and television.

Overview

[edit]When an information-bearing signal passes through a communication channel, it is progressively degraded due to loss of power. For example, when a telephone call passes through a wire telephone line, some of the power in the electric current which represents the audio signal is dissipated as heat in the resistance of the copper wire. The longer the wire, the more power is lost, and the smaller the amplitude of the signal at the far end. So with a long enough wire the call will not be audible at the other end. Similarly, the greater the distance between a radio station and a receiver, the weaker the radio signal, and the poorer the reception. A repeater is an electronic device in a communication channel that increases the power of a signal and retransmits it, allowing it to travel further. Since it amplifies the signal, it requires a source of electric power.

The term "repeater" originated with telegraphy in the 19th century, and referred to an electromechanical device (a relay) used to regenerate telegraph signals.[1][2]

Use of the term has continued in telephony and data communications.

In computer networking, because repeaters work with the actual physical signal, and do not attempt to interpret the data being transmitted, they operate on the physical layer, the first layer of the OSI model; a multiport Ethernet repeater is usually called a hub.

Types

[edit]Telephone repeater

[edit]This is used to increase the range of telephone signals in a telephone line.

- Land line repeater

They are most frequently used in trunklines that carry long distance calls. In an analog telephone line consisting of a pair of wires, it consists of an amplifier circuit made of transistors which use power from a DC current source to increase the power of the alternating current audio signal on the line. Since the telephone is a duplex (bidirectional) communication system, the wire pair carries two audio signals, one going in each direction. So telephone repeaters have to be bilateral, amplifying the signal in both directions without causing feedback, which complicates their design considerably. Telephone repeaters were the first type of repeater and were some of the first applications of amplification. The development of telephone repeaters between 1900 and 1915 made long-distance phone service possible. Now, most telecommunications cables are fiber-optic cables which use optical repeaters (below).

Before the invention of electronic amplifiers, mechanically coupled carbon microphones were used as amplifiers in telephone repeaters. After the turn of the 20th century it was found that negative resistance mercury lamps could amplify, and they were used.[3] The invention of audion tube repeaters around 1916 made transcontinental telephony practical. In the 1930s vacuum tube repeaters using hybrid coils became commonplace, allowing the use of thinner wires. In the 1950s negative impedance gain devices were more popular, and a transistorized version called the E6 repeater was the final major type used in the Bell System before the low cost of digital transmission made all voiceband repeaters obsolete. Frequency frogging repeaters were commonplace in frequency-division multiplexing systems from the middle to late 20th century.

- Submarine cable repeater

This is a type of telephone repeater used in underwater submarine telecommunications cables.

Optical communications repeater

[edit]This is used to increase the range of signals in a fiber-optic cable. Digital information travels through a fiber-optic cable in the form of short pulses of light. The light is made up of particles called photons, which can be absorbed or scattered in the fiber. An optical communications repeater usually consists of a phototransistor which converts the light pulses to an electrical signal, an amplifier to increase the power of the signal, an electronic filter which reshapes the pulses, and a laser which converts the electrical signal to light again and sends it out the other fiber. However, optical amplifiers are being developed for repeaters to amplify the light itself without the need of converting it to an electric signal first.

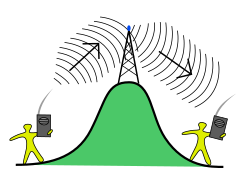

Radio repeater

[edit]

This is used to extend the range of coverage of a radio signal. The history of radio relay repeaters began in 1898 from the publication by Johann Mattausch in Austrian Journal Zeitschrift für Electrotechnik (v. 16, 35 - 36).[2][4] But his proposal "Translator" was primitive and not suitable for use. The first relay system with radio repeaters, which really functioned, was that invented in 1899 by Emile Guarini-Foresio.[2]

A radio repeater usually consists of a radio receiver connected to a radio transmitter. The received signal is amplified and retransmitted, often on another frequency, to provide coverage beyond the obstruction. Usage of a duplexer can allow the repeater to use one antenna for both receive and transmit at the same time.

- Broadcast relay station, rebroadcastor or translator: This is a repeater used to extend the coverage of a radio or television broadcasting station. It consists of a secondary radio or television transmitter. The signal from the main transmitter often comes over leased telephone lines or by microwave relay.

- Microwave relay: This is a specialized point-to-point telecommunications link, consisting of a microwave receiver that receives information over a beam of microwaves from another relay station in line-of-sight distance, and a microwave transmitter which passes the information on to the next station over another beam of microwaves. Networks of microwave relay stations transmit telephone calls, television programs, and computer data from one city to another over continent-wide areas.

- Passive repeater: This is a microwave relay that simply consists of a flat metal surface to reflect the microwave beam in another direction. It is used to get microwave relay signals over hills and mountains when it is not necessary to amplify the signal.

- Cellular repeater: This is a radio repeater for boosting cell phone reception in a limited area. The device functions like a small cellular base station, with a directional antenna to receive the signal from the nearest cell tower, an amplifier, and a local antenna to rebroadcast the signal to nearby cell phones. It is often used in downtown office buildings.

- Digipeater: A repeater node in a packet radio network. It performs a store and forward function, passing on packets of information from one node to another.

- Amateur radio repeater: Used by amateur radio operators to enable two-way communication across an area which would otherwise be difficult by point-to-point on VHF and UHF. These repeaters are set up and maintained by individual operators or clubs, and are generally available for any licensed amateur to use. A hill or mountaintop location is a preferable location to construct a repeater, as it will maximize the usability across a large area.

Radio repeaters improve communication coverage in systems using frequencies that typically have line-of-sight propagation. Without a repeater, these systems are limited in range by the curvature of the Earth and the blocking effect of terrain or high buildings. A repeater on a hilltop or tall building can allow stations that are out of each other's line-of-sight range to communicate reliably.[5]

Radio repeaters may also allow translation from one set of radio frequencies to another, for example to allow two different public service agencies to interoperate (say, police and fire services of a city, or neighboring police departments). They may provide links to the public switched telephone network as well,[6][7] or satellite network (BGAN, INMARSAT, MSAT) as an alternative path from source to the destination.[8]

Typically a repeater station listens on one frequency, A, and transmits on a second, B. All mobile stations listen for signals on channel B and transmit on channel A. The difference between the two frequencies may be relatively small compared to the frequency of operation, say 1%. Often the repeater station will use the same antenna for transmission and reception; highly selective filters called "duplexers" separate the faint incoming received signal from the billions of times more powerful outbound transmitted signal. Sometimes separate transmitting and receiving locations are used, connected by a wire line or a radio link. While the repeater station is designed for simultaneous reception and transmission, mobile units need not be equipped with the bulky and costly duplexers, as they only transmit or receive at any time.

Mobile units in a repeater system may be provided with a "talkaround" channel that allows direct mobile-to-mobile operation on a single channel. This may be used if out of reach of the repeater system, or for communications not requiring the attention of all mobiles. The "talkaround" channel may be the repeater output frequency; the repeater will not retransmit any signals on its output frequency.[9]

An engineered radio communication system designer will analyze the coverage area desired and select repeater locations, elevations, antennas, operating frequencies and power levels to permit a predictable level of reliable communication over the designed coverage area.

Data handling

[edit]Repeaters can be divided into two types depending on the type of data they handle:

Analog repeater

[edit]This type is used in channels that transmit data in the form of an analog signal in which the voltage or current is proportional to the amplitude of the signal, as in an audio signal. They are also used in trunklines that transmit multiple signals using frequency division multiplexing (FDM). Analog repeaters are composed of a linear amplifier, and may include electronic filters to compensate for frequency and phase distortion in the line.

Digital repeater

[edit]The digital repeater is used in channels that transmit data by binary digital signals, in which the data is in the form of pulses with only two possible values, representing the binary digits 1 and 0. A digital repeater amplifies the signal, and it also may retime, resynchronize, and reshape the pulses. A repeater that performs the retiming or resynchronizing functions may be called a regenerator.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Loring, A. E.E (1878). A Hand-book of the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph. New York: D. Van Nostrand. pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c Slyusar, Vadym (2015). "First Antennas for Relay Stations" (PDF). International Conference on Antenna Theory and Techniques, 21–24 April 2015. Kharkiv, Ukraine. pp. 254–255. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Sungook, Hong (2001). Wireless: From Marconi's Black-Box to the Audion. MIT Press. p. 165. ISBN 0262082985.

- ^ Mattausch J. Telegraphie ohne Draht. Eine Studie. // Zeitschrift für Elektrotechnik. Organ des Elektrotechnischen Vereines in Wien.- Heft 3, 16. Jänner 1898. - XVI. Jahrgang. - S. 35–36.[1] Archived 2017-08-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Radio Awareness about Communications Systems - HOW DO REPEATER SYSTEMS WORK?". .taitradioacademy.com/. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Radio Interoperability Communications Systems -". basecampconnect.com. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Radio Interoperability - TELEPHONE INTERCONNECT-". codanradio.com/. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ "Tactical Voice Communications Solutions for HLD/HLS" (PDF). c-at.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2017-08-23.

- ^ Land mobile radio systems - 2nd ed. Improving and Extending Area Coverage (Englewood Cliffs, NJ : PTR Prentice Hall, 1994) ISBN 0131231596, p. 67-75.

External links

[edit]- The Bell system technical journal: Repeaters and Equalizers for the SD Submarine Cable System

- Amateur Radio Repeaters in India Archived 2017-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Amateur Radio Repeaters in Europe