Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Photodiode

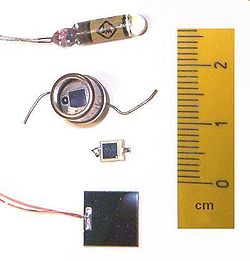

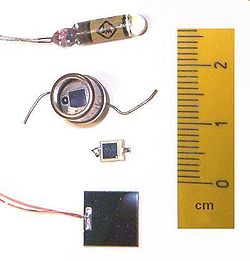

View on Wikipedia One Ge (top) and three Si (bottom) photodiodes | |

| Component type | Passive, diode |

|---|---|

| Working principle | Converts light into current |

| Pin names | anode and cathode |

| Electronic symbol | |

A photodiode is a semiconductor diode sensitive to photon radiation, such as visible light, infrared or ultraviolet radiation, X-rays and gamma rays.[1] It produces an electrical current when it absorbs photons. This can be used for detection and measurement applications, or for the generation of electrical power in solar cells. Photodiodes are used in a wide range of applications throughout the electromagnetic spectrum from visible light photocells to gamma ray spectrometers.

Principle of operation

[edit]A photodiode is a PIN structure or p–n junction. When a photon of sufficient energy strikes the diode, it creates an electron–hole pair. This mechanism is also known as the inner photoelectric effect. If the absorption occurs in the junction's depletion region, or one diffusion length away from it, these carriers are swept from the junction by the built-in electric field of the depletion region. Thus holes move toward the anode, and electrons toward the cathode, and a photocurrent is produced. The total current through the photodiode is the sum of the dark current (current that is passed in the absence of light) and the photocurrent, so the dark current must be minimized to maximize the sensitivity of the device.[2] Therefore, photodiodes operate most ideally in reverse bias.

To first order, for a given spectral distribution, the photocurrent is linearly proportional to the irradiance.[3]

Photovoltaic mode

[edit]

In photovoltaic mode (zero bias), photocurrent flows into the anode through a short circuit to the cathode. If the circuit is opened or has a load impedance, restricting the photocurrent out of the device, a voltage builds up in the direction that forward biases the diode, that is, anode positive with respect to cathode. If the circuit is shorted or the impedance is low, a forward current will consume all or some of the photocurrent. This mode exploits the photovoltaic effect, which is the basis for solar cells – a traditional solar cell is just a large area photodiode. For optimum power output, the photovoltaic cell will be operated at a voltage that causes only a small forward current compared to the photocurrent.[3]

Photoconductive mode

[edit]In photoconductive mode the diode is reverse biased, that is, with the cathode driven positive with respect to the anode. This reduces the response time because the additional reverse bias increases the width of the depletion layer, which decreases the junction's capacitance and increases the region with an electric field that will cause electrons to be quickly collected. The reverse bias also creates dark current without much change in the photocurrent.

Although this mode is faster, the photoconductive mode can exhibit more electronic noise due to dark current or avalanche effects.[4] The leakage current of a good PIN diode is so low (<1 nA) that the Johnson–Nyquist noise of the load resistance in a typical circuit often dominates.

Related devices

[edit]Avalanche photodiodes are photodiodes with structure optimized for operating with high reverse bias, approaching the reverse breakdown voltage. This allows each photo-generated carrier to be multiplied by avalanche breakdown, resulting in internal gain within the photodiode, which increases the effective responsivity of the device.[5]

A phototransistor is a light-sensitive transistor. A common type of phototransistor, the bipolar phototransistor, is in essence a bipolar transistor encased in a transparent case so that light can reach the base–collector junction. It was invented by John N. Shive at Bell Labs in 1948[6]: 205 but it was not announced until 1950.[7] The electrons that are generated by photons in the base–collector junction are injected into the base, and this photodiode current is amplified by the transistor's current gain β (or hfe). If the base and collector leads are used and the emitter is left unconnected, the phototransistor becomes a photodiode. While phototransistors have a higher responsivity for light they are not able to detect low levels of light any better than photodiodes.[citation needed] Phototransistors also have significantly longer response times. Another type of phototransistor, the field-effect phototransistor (also known as photoFET), is a light-sensitive field-effect transistor. Unlike photobipolar transistors, photoFETs control drain-source current by creating a gate voltage.

A solaristor is a two-terminal gate-less phototransistor. A compact class of such solaristors was demonstrated in 2018 by ICN2 researchers. The novel concept is a two-in-one power source plus transistor device that runs on solar energy by exploiting a memresistive effect in the flow of photogenerated carriers.[8]

Materials

[edit]The material used to make a photodiode is critical to defining its properties, because only photons with sufficient energy to excite electrons across the material's bandgap will produce significant photocurrents.

Materials commonly used to produce photodiodes are listed in the table below.[9]

| Material | Electromagnetic spectrum wavelength range (nm) |

|---|---|

| Silicon | 190–1100 |

| Germanium | 400–1700 |

| Indium gallium arsenide | 800–2600 |

| Lead(II) sulfide | <1000–3500 |

| Mercury cadmium telluride | 400–14000 |

Because of their greater bandgap, silicon-based photodiodes generate less noise than germanium-based photodiodes.

Binary materials, such as MoS2, and graphene emerged as new materials for the production of photodiodes.[10]

Unwanted and wanted photodiode effects

[edit]Any p–n junction, if illuminated, is potentially a photodiode. Semiconductor devices such as diodes, transistors and ICs contain p–n junctions, and will not function correctly if they are illuminated by unwanted light.[11][12] This is avoided by encapsulating devices in opaque housings. If these housings are not completely opaque to high-energy radiation (ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays), diodes, transistors and ICs can malfunction[13] due to induced photo-currents. Background radiation from the packaging is also significant.[14] Radiation hardening mitigates these effects.

In some cases, the effect is actually wanted, for example to use LEDs as light-sensitive devices (see LED as light sensor) or even for energy harvesting, then sometimes called light-emitting and light-absorbing diodes (LEADs).[15]

Features

[edit]

Critical performance parameters of a photodiode include spectral responsivity, dark current, response time and noise-equivalent power.

- Spectral responsivity

- The spectral responsivity is a ratio of the generated photocurrent to incident light power, expressed in A/W when used in photoconductive mode. The wavelength-dependence may also be expressed as a quantum efficiency or the ratio of the number of photogenerated carriers to incident photons which is a unitless quantity.

- Dark current

- The dark current is the current through the photodiode in the absence of light, when it is operated in photoconductive mode. The dark current includes photocurrent generated by background radiation and the saturation current of the semiconductor junction. Dark current must be accounted for by calibration if a photodiode is used to make an accurate optical power measurement, and it is also a source of noise when a photodiode is used in an optical communication system.

- Response time

- The response time is the time required for the detector to respond to an optical input. A photon absorbed by the semiconducting material will generate an electron–hole pair which will in turn start moving in the material under the effect of the electric field and thus generate a current. The finite duration of this current is known as the transit-time spread and can be evaluated by using Ramo's theorem. One can also show with this theorem that the total charge generated in the external circuit is e and not 2e as one might expect by the presence of the two carriers. Indeed, the integral of the current due to both electron and hole over time must be equal to e. The resistance and capacitance of the photodiode and the external circuitry give rise to another response time known as RC time constant (). This combination of R and C integrates the photoresponse over time and thus lengthens the impulse response of the photodiode. When used in an optical communication system, the response time determines the bandwidth available for signal modulation and thus data transmission.

- Noise-equivalent power

- Noise-equivalent power (NEP) is the minimum input optical power to generate photocurrent, equal to the rms noise current in a 1 hertz bandwidth. NEP is essentially the minimum detectable power. The related characteristic detectivity () is the inverse of NEP (1/NEP) and the specific detectivity () is the detectivity multiplied by the square root of the area () of the photodetector () for a 1 Hz bandwidth. The specific detectivity allows different systems to be compared independent of sensor area and system bandwidth; a higher detectivity value indicates a low-noise device or system.[16] Although it is traditional to give () in many catalogues as a measure of the diode's quality, in practice, it is hardly ever the key parameter.

When a photodiode is used in an optical communication system, all these parameters contribute to the sensitivity of the optical receiver which is the minimum input power required for the receiver to achieve a specified bit error rate.

Applications

[edit]P–n photodiodes are used in similar applications to other photodetectors, such as photoconductors, charge-coupled devices (CCD), and photomultiplier tubes. They may be used to generate an output which is dependent upon the illumination (analog for measurement), or to change the state of circuitry (digital, either for control and switching or for digital signal processing).

Photodiodes are used in consumer electronics devices such as compact disc players, smoke detectors, medical devices[17] and the receivers for infrared remote control devices used to control equipment from televisions to air conditioners. For many applications either photodiodes or photoconductors may be used. Either type of photosensor may be used for light measurement, as in camera light meters, or to respond to light levels, as in switching on street lighting after dark.

Photosensors of all types may be used to respond to incident light or to a source of light which is part of the same circuit or system. A photodiode is often combined into a single component with an emitter of light, usually a light-emitting diode (LED), either to detect the presence of a mechanical obstruction to the beam (slotted optical switch) or to couple two digital or analog circuits while maintaining extremely high electrical isolation between them, often for safety (optocoupler). The combination of LED and photodiode is also used in many sensor systems to characterize different types of products based on their optical absorbance.

Photodiodes are often used for accurate measurement of light intensity in science and industry. They generally have a more linear response than photoconductors.

They are also widely used in various medical applications, such as detectors for computed tomography (coupled with scintillators), instruments to analyze samples (immunoassay), and pulse oximeters.

PIN diodes are much faster and more sensitive than p–n junction diodes, and hence are often used for optical communications and in lighting regulation.

P–n photodiodes are not used to measure extremely low light intensities. Instead, if high sensitivity is needed, avalanche photodiodes, intensified charge-coupled devices or photomultiplier tubes are used for applications such as astronomy, spectroscopy, night vision equipment and laser rangefinding.

Comparison with photomultipliers

[edit]Advantages compared to photomultipliers:[18]

- Excellent linearity of output current as a function of incident light

- Spectral response from 190 nm to 1100 nm (silicon), longer wavelengths with other semiconductor materials

- Low noise

- Ruggedized to mechanical stress

- Low cost

- Compact and light weight

- Long lifetime

- High quantum efficiency, typically 60–80%[19]

- No high voltage required

Disadvantages compared to photomultipliers:

- Small area

- No internal gain (except avalanche photodiodes, but their gain is typically 102–103 compared to 105-108 for the photomultiplier)

- Much lower overall sensitivity

- Photon counting only possible with specially designed, usually cooled photodiodes, with special electronic circuits

- Response time for many designs is slower

- Latent effect

Pinned photodiode

[edit]The pinned photodiode (PPD) has a shallow implant (P+ or N+) in N-type or P-type diffusion layer, respectively, over a P-type or N-type (respectively) substrate layer, such that the intermediate diffusion layer can be fully depleted of majority carriers, like the base region of a bipolar junction transistor. The PPD (usually PNP) is used in CMOS active-pixel sensors; a precursor NPNP triple junction variant with the MOS buffer capacitor and the back-light illumination scheme with complete charge transfer and no image lag was invented by Sony in 1975. This scheme was widely used in many applications of charge transfer devices.

Early charge-coupled device image sensors suffered from shutter lag. This was largely explained with the re-invention of the pinned photodiode.[20] It was developed by Nobukazu Teranishi, Hiromitsu Shiraki and Yasuo Ishihara at NEC in 1980.[20][21] Sony in 1975 recognized that lag can be eliminated if the signal carriers could be transferred from the photodiode to the CCD. This led to their invention of the pinned photodiode, a photodetector structure with low lag, low noise, high quantum efficiency and low dark current.[20] It was first publicly reported by Teranishi and Ishihara with A. Kohono, E. Oda and K. Arai in 1982, with the addition of an anti-blooming structure.[20][22] The new photodetector structure invented by Sony in 1975, developed by NEC in 1982 by Kodak in 1984 was given the name "pinned photodiode" (PPD) by B.C. Burkey at Kodak in 1984. In 1987, the PPD began to be incorporated into most CCD sensors, becoming a fixture in consumer electronic video cameras and then digital still cameras.[20]

A CMOS image sensor with a low-voltage-PPD technology was first fabricated in 1995 by a joint JPL and Kodak team. The CMOS sensor with PPD technology was further advanced and refined by R.M. Guidash in 1997, K. Yonemoto and H. Sumi in 2000, and I. Inoue in 2003. This led to CMOS sensors achieve imaging performance on par with CCD sensors, and later exceeding CCD sensors.

Photodiode array

[edit]

A one-dimensional array of hundreds or thousands of photodiodes can be used as a position sensor, for example as part of an angle sensor.[23] A two-dimensional array is used in image sensors and optical mice.

In some applications, photodiode arrays allow for high-speed parallel readout, as opposed to integrating scanning electronics as in a charge-coupled device (CCD) or CMOS sensor. The optical mouse chip shown in the photo has parallel (not multiplexed) access to all 16 photodiodes in its 4 × 4 array.

Passive-pixel image sensor

[edit]The passive-pixel sensor (PPS) is a type of photodiode array. It was the precursor to the active-pixel sensor (APS).[20] A passive-pixel sensor consists of passive pixels which are read out without amplification, with each pixel consisting of a photodiode and a MOSFET switch.[24] In a photodiode array, pixels contain a p–n junction, integrated capacitor, and MOSFETs as selection transistors. A photodiode array was proposed by G. Weckler in 1968, predating the CCD.[25] This was the basis for the PPS.[20]

The noise of photodiode arrays is sometimes a limitation to performance. It was not possible to fabricate active pixel sensors with a practical pixel size in the 1970s, due to limited microlithography technology at the time.[25]

See also

[edit]- Electronics

- Band gap

- Infrared

- Optoelectronics

- Optical interconnect

- Light Peak

- Interconnect bottleneck

- Optical fiber cable

- Optical communication

- Parallel optical interface

- Opto-isolator

- Semiconductor device

- Solar cell

- Avalanche photodiode

- Transducer

- LEDs as photodiode light sensors

- Light meter

- Image sensor

- Transimpedance amplifier

- Photoelectric sensor

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on 2022-01-22.

- ^ Pearsall, Thomas (2010). Photonics Essentials, 2nd edition. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-162935-5. Archived from the original on 2021-08-17. Retrieved 2021-02-25.

- ^ Tavernier, Filip and Steyaert, Michiel (2011) High-Speed Optical Receivers with Integrated Photodiode in Nanoscale CMOS. Springer. ISBN 1-4419-9924-8. Chapter 3 From Light to Electric Current – The Photodiode

- ^ a b Häberlin, Heinrich (2012). Photovoltaics: System Design and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. pp. SA3–PA11–14. ISBN 978-1-119-97838-1. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ "Photodiode Application Notes – Excelitas – see note 4" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-13. Retrieved 2014-11-13.

- ^ Pearsall, Thomas; Pollack, Martin (1985). Compound Semiconductor Photodiodes, Semiconductors and Semimetals, Vol 22D. Elsevier. pp. 173–245. doi:10.1016/S0080-8784(08)62953-1.

- ^ Riordan, Michael; Hoddeson, Lillian (1998). Crystal Fire: The Invention of the Transistor and the Birth of the Information Age. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31851-7.

- ^ "The phototransistor". Bell Laboratories Record. May 1950. Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- ^ Pérez-Tomás, Amador; Lima, Anderson; Billon, Quentin; Shirley, Ian; Catalan, Gustau; Lira-Cantú, Mónica (2018). "A Solar Transistor and Photoferroelectric Memory". Advanced Functional Materials. 28 (17) 1707099. doi:10.1002/adfm.201707099. hdl:10261/199048. ISSN 1616-3028. S2CID 102819292.

- ^ Held. G, Introduction to Light Emitting Diode Technology and Applications, CRC Press, (Worldwide, 2008). Ch. 5 p. 116. ISBN 1-4200-7662-0

- ^ Yin, Zongyou; Li, Hai; Li, Hong; Jiang, Lin; Shi, Yumeng; Sun, Yinghui; Lu, Gang; Zhang, Qing; Chen, Xiaodong; Zhang, Hua (21 December 2011). "Single-Layer MoS Phototransistors". ACS Nano. 6 (1): 74–80. arXiv:1310.8066. doi:10.1021/nn2024557. PMID 22165908. S2CID 27038582.

- ^ Shanfield, Z. et al (1988) Investigation of radiation effects on semiconductor devices and integrated circuits[dead link], DNA-TR-88-221

- ^ Iniewski, Krzysztof (ed.) (2010), Radiation Effects in Semiconductors, CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4398-2694-2

- ^ Zeller, H.R. (1995). "Cosmic ray induced failures in high power semiconductor devices". Solid-State Electronics. 38 (12): 2041–2046. Bibcode:1995SSEle..38.2041Z. doi:10.1016/0038-1101(95)00082-5.

- ^ May, T.C.; Woods, M.H. (1979). "Alpha-particle-induced soft errors in dynamic memories". IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices. 26 (1): 2–9. Bibcode:1979ITED...26....2M. doi:10.1109/T-ED.1979.19370. S2CID 43748644. Cited in Baumann, R. C. (2004). "Soft errors in commercial integrated circuits". International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems. 14 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1142/S0129156404002363.

alpha particles emitted from the natural radioactive decay of uranium, thorium, and daughter isotopes present as impurities in packaging materials were found to be the dominant cause of [soft error rate] in [dynamic random-access memories].

- ^ Erzberger, Arno (2016-06-21). "Halbleitertechnik Der LED fehlt der Doppelpfeil". Elektronik (in German). Archived from the original on 2017-02-14. Retrieved 2017-02-14.

- ^ Brooker, Graham (2009) Introduction to Sensors for Ranging and Imaging, ScitTech Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 9781891121746

- ^ E. Aguilar Pelaez et al., "LED power reduction trade-offs for ambulatory pulse oximetry," 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, Lyon, 2007, pp. 2296–2299. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4352784, URL: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=4352784&isnumber=4352185

- ^ Photodiode Technical Guide Archived 2007-01-04 at the Wayback Machine on Hamamatsu website

- ^ Knoll, F.G. (2010). Radiation detection and measurement, 4th ed. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-470-13148-0

- ^ a b c d e f g Fossum, Eric R.; Hondongwa, D. B. (2014). "A Review of the Pinned Photodiode for CCD and CMOS Image Sensors". IEEE Journal of the Electron Devices Society. 2 (3): 33–43. Bibcode:2014IJEDS...2...33F. doi:10.1109/JEDS.2014.2306412.

- ^ U.S. Patent 4,484,210, which was a floating-surface type buried photodioe with the similar structure of the 1975 Philips invention. Solid-state imaging device having a reduced image lag

- ^ Teranishi, Nobuzaku; Kohono, A.; Ishihara, Yasuo; Oda, E.; Arai, K. (December 1982). "No image lag photodiode structure in the interline CCD image sensor". 1982 International Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 324–327. doi:10.1109/IEDM.1982.190285. S2CID 44669969.

- ^ Gao, Wei (2010). Precision Nanometrology: Sensors and Measuring Systems for Nanomanufacturing. Springer. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-84996-253-7.

- ^ Kozlowski, L. J.; Luo, J.; Kleinhans, W. E.; Liu, T. (14 September 1998). Pain, Bedabrata; Lomheim, Terrence S. (eds.). "Comparison of passive and active pixel schemes for CMOS visible imagers". Infrared Readout Electronics IV. 3360. International Society for Optics and Photonics: 101–110. Bibcode:1998SPIE.3360..101K. doi:10.1117/12.584474. S2CID 123351913.

- ^ a b Fossum, Eric R. (12 July 1993). "Active pixel sensors: Are CCDS dinosaurs?". In Blouke, Morley M. (ed.). Charge-Coupled Devices and Solid State Optical Sensors III. Vol. 1900. International Society for Optics and Photonics. pp. 2–14. Bibcode:1993SPIE.1900....2F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.408.6558. doi:10.1117/12.148585. S2CID 10556755.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

External links

[edit]- Photodiode I–V characteristics Archived 2022-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Using the Photodiode to convert the PC to a Light Intensity Logger

- Design Fundamentals for Phototransistor Circuits (archived on February 5, 2005)

- Working principles of photodiodes Archived 2009-02-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Excelitas Application Notes on Pacer Website (archived on March 4, 2016)

Photodiode

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Operation

A photodiode is a p-n junction semiconductor device that converts incident light into electrical current by generating charge carriers through photon absorption, with the resulting photocurrent being proportional to the light intensity.[7][8] The core structure consists of a p-type semiconductor region doped with acceptors, an n-type region doped with donors, forming the p-n junction, along with a depletion region at the interface where mobile charges are scarce, and terminals designated as the anode (connected to the p-side) and cathode (connected to the n-side).[8][9] In its basic operation, light photons with energy greater than the semiconductor's bandgap are absorbed, primarily in or near the depletion region, exciting electrons from the valence band to the conduction band and creating electron-hole pairs.[7] The built-in electric field across the depletion region separates these carriers, with electrons drifting toward the n-side and holes toward the p-side, producing a measurable photocurrent in an external circuit.[8][10] This process relies on the photovoltaic effect inherent to the p-n junction, enabling the device to function as an optical detector without external amplification in simple configurations.[11] Under zero bias, where no external voltage is applied across the terminals, the photodiode's current-voltage (I-V) characteristic shifts due to illumination, generating an open-circuit voltage proportional to the logarithm of the light intensity as the photocurrent flows through the device's internal resistance.[11][12] This voltage buildup occurs because the generated photocurrent is restricted by the forward-biased junction, creating a potential difference that can power low-current loads directly.[8] A key performance metric is the quantum efficiency (η), defined as the ratio of the number of charge carriers collected at the electrodes to the number of incident photons: This parameter quantifies the device's efficiency in converting photons to electrical signal, typically expressed as a percentage, and depends on factors like absorption coefficient and carrier collection probability within the active region.[9][8][11]Historical Development

The photovoltaic effect, foundational to photodiode operation, was first observed in 1839 by French physicist Edmond Becquerel, who noted that certain materials exposed to light in an electrolytic solution generated a voltage.[13] This discovery laid the groundwork for light-sensitive devices, though practical applications remained elusive for decades. In 1873, English engineer Willoughby Smith reported the photoconductivity of selenium, demonstrating that the material's electrical resistance decreased under illumination, enabling the creation of early selenium-based photodetectors used in telegraphy and light measurement.[14] The modern era of photodiodes began in the mid-20th century with advancements in semiconductor technology at Bell Laboratories. In 1941, Russell Ohl accidentally discovered a p-n junction in a silicon crystal that produced a photovoltaic response to light, patenting the concept and paving the way for the first practical silicon p-n junction photodiodes by the early 1950s.[14] This breakthrough shifted focus from brittle selenium cells to more robust silicon devices, improving sensitivity and reliability for applications like solar energy and optical sensing. Concurrently, Japanese researcher Jun-ichi Nishizawa invented the PIN diode structure in 1950 and extended it to the PIN photodiode in 1952, introducing an intrinsic layer between p- and n-regions to enhance light absorption and reduce capacitance.[15] Key milestones in the 1960s and 1970s advanced photodiode performance for specialized uses. PIN photodiodes gained prominence in the 1960s for telecommunications, supporting early fiber-optic systems with their low noise and high-speed response.[16] Avalanche photodiodes, also pioneered by Nishizawa in 1952, saw practical development in the 1970s for low-light detection, leveraging internal gain mechanisms to amplify signals in applications like lidar and scientific instrumentation.[17] In 1975, Sony's Yoshiaki Hagiwara invented the pinned photodiode, which facilitated integration into charge-coupled devices (CCDs) and later CMOS sensors in the 1980s, revolutionizing imaging in consumer electronics such as cameras.[18] Entering the 21st century, photodiodes evolved toward advanced materials for broader spectral coverage and efficiency. Post-2000 developments emphasized III-V compound semiconductors like InGaAs for infrared detection, enabling high-performance devices in telecom and sensing.[19] Recent advances up to 2025 include perovskite-based photodiodes, with significant progress since the 2010s yielding fast, stable detectors for imaging and optoelectronics through solution-processable fabrication.[20] Similarly, two-dimensional materials such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides have driven innovations in flexible, high-efficiency photodiodes, addressing limitations in traditional silicon for wearable and broadband applications.[21] These shifts have transformed photodiodes from discrete components into integral parts of integrated circuits, powering modern consumer electronics and optical systems.Operating Principles

Photovoltaic Mode

In photovoltaic mode, a photodiode operates without any external bias voltage, relying on the built-in potential difference across the p-n junction to separate photogenerated charge carriers. When photons with energy greater than the semiconductor bandgap are absorbed, they create electron-hole pairs primarily in or near the depletion region. These carriers are separated by the internal electric field: electrons drift toward the n-side and holes toward the p-side, generating a photocurrent that can produce a measurable voltage across the device terminals. This mode leverages the photovoltaic effect, similar to that in solar cells, but is tailored for light detection rather than efficient power conversion.[22] The carrier dynamics in this mode involve both diffusion and drift processes. Generated electron-hole pairs in the neutral regions diffuse randomly until reaching the depletion region, where the strong built-in field sweeps them apart efficiently, minimizing recombination. Under short-circuit conditions (zero voltage across the device), the resulting current flows freely, while in open-circuit conditions, carrier accumulation builds up a voltage opposing further separation. The short-circuit current is expressed as where is the elementary charge, is the quantum efficiency, is the incident optical power, is the active area, and is the photon energy. The open-circuit voltage is approximated by the diode equation where is Boltzmann's constant, is the absolute temperature, and is the dark saturation current.[22][12] This operating mode offers distinct advantages, including very low noise due to negligible dark current and the ability to function in a self-powered manner without external circuitry. However, it has limitations such as slower response times compared to biased modes, as the absence of an external field reduces carrier collection efficiency and increases transit times. Photodiodes in photovoltaic mode are optimized for precise light detection with linear response to intensity, differing from solar cells which prioritize maximizing power output through larger areas and specific material choices.[23][12]Photoconductive Mode

In photoconductive mode, a reverse bias voltage is applied across the photodiode, widening the depletion region compared to zero-bias operation and thereby improving the separation and collection efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs while reducing junction capacitance.[24] This bias configuration causes the device to function as a light-dependent resistor, where the generated current varies directly with the intensity of incident light, enabling precise measurement of optical power.[25] The photocurrent in this mode is expressed as , where is the responsivity (typically in A/W) and is the incident optical power; the total current is then , with the dark current increasing under the applied reverse bias voltage .[24] The 3 dB bandwidth, which determines the frequency response, is influenced by the junction capacitance and is commonly limited by the RC time constant, approximated as , where is the load resistance; higher reverse bias reduces , extending the bandwidth for faster operation.[24] Linearity in photoconductive mode is a key feature, with the output current maintaining a proportional relationship to light intensity across several orders of magnitude until saturation occurs, and the applied bias voltage enhances this by minimizing carrier recombination and diffusion effects that could introduce nonlinearity.[8] This mode offers advantages such as superior speed and reduced capacitance relative to unbiased operation, rendering it ideal for high-frequency applications like fiber-optic communications and laser ranging systems.[26]Materials and Fabrication

Semiconductor Materials

Silicon is the most widely used semiconductor material for photodiodes operating in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectrum, with a bandgap energy of 1.12 eV that enables efficient absorption of photons up to approximately 1100 nm.[27] Germanium, featuring a narrower bandgap of 0.67 eV, extends sensitivity into the infrared region up to about 1700 nm, making it suitable for mid-IR detection. Gallium arsenide (GaAs) photodiodes, with a bandgap of 1.43 eV, target NIR applications around 870 nm, offering higher electron mobility compared to silicon for faster response times.[25] Indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs), tunable with a bandgap around 0.75 eV, provides extended NIR coverage up to 1.7 μm, ideal for telecommunications wavelengths.[25] Key material properties influencing photodiode performance include the wavelength-dependent absorption coefficient α(λ), which quantifies how strongly light is absorbed; the penetration depth, given by 1/α, determines the optimal placement of the p-n junction to maximize carrier collection efficiency.[27] For instance, silicon exhibits α values on the order of 10^4 cm⁻¹ at 800 nm, leading to shallow penetration depths of about 1 μm, while germanium's lower α in the IR necessitates thicker absorption layers.[28] Carrier mobility, measuring charge transport speed, and minority carrier lifetime, affecting recombination rates, directly impact response time; high-mobility materials like GaAs (electron mobility ~8500 cm²/V·s) enable bandwidths exceeding 10 GHz.[29] Material selection for photodiodes hinges on the target wavelength range from ultraviolet to infrared, with silicon dominating UV-visible applications due to its broad absorption and temperature stability up to 150°C.[25] Temperature stability is critical, as bandgap energies decrease with rising temperature, shifting absorption edges; III-V compounds like InGaAs maintain performance better in harsh environments than germanium. Cost-performance trade-offs favor silicon for low-cost, high-volume visible detectors, while III-V materials such as GaAs and InGaAs are preferred for high-speed telecom despite higher fabrication expenses.[25] Emerging materials as of 2025 include halide perovskites, which offer broadband absorption and high quantum efficiencies, often approaching 90% in optimized visible-NIR devices, though stability issues under humidity and heat limit commercial adoption.[30] Two-dimensional materials like graphene enable ultrafast detection with response times on the order of picoseconds to nanoseconds, benefiting from high carrier mobilities exceeding 10,000 cm²/V·s at room temperature, but challenges in bandgap engineering and integration persist.[21] Doping levels in these materials form the p-n junction essential for carrier separation; in silicon, p-type doping typically uses boron at concentrations of 10^{15}-10^{18} cm^{-3} to create acceptor sites, while n-type doping employs phosphorus at similar levels to provide donor electrons.[31]| Material | Bandgap (eV) | Wavelength Range (nm) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon (Si) | 1.12 | 300-1100 | Visible-NIR detection |

| Germanium (Ge) | 0.67 | 400-1700 | Mid-IR sensing |

| Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) | 1.43 | 200-870 | High-speed NIR |

| Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) | ~0.75 | 900-1700 | Telecom wavelengths |

Fabrication Techniques

The fabrication of photodiodes begins with wafer preparation, where high-purity semiconductor substrates are produced to ensure minimal defects and uniform electrical properties. For silicon-based photodiodes, the Czochralski process is widely employed to grow single-crystal ingots from a molten silicon source, followed by slicing into wafers that serve as the foundation for device layers. Doping of these wafers to create n-type or p-type regions is achieved through diffusion, where dopant atoms like phosphorus or boron are introduced via thermal processes, or ion implantation, which accelerates dopant ions into the lattice for precise control over concentration profiles.[32] These steps are critical for establishing the base conductivity and junction characteristics essential to photodiode functionality. Junction formation follows wafer preparation, particularly for PIN structures that require an intrinsic region to minimize capacitance and enhance speed. Epitaxial growth techniques such as metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD) or molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) are used to deposit the intrinsic layer with atomic-level precision on the doped substrate, enabling low-defect interfaces and tailored bandgap properties. For instance, MOCVD facilitates uniform deposition of III-V materials like InGaAs for near-infrared detection, while MBE offers superior control for lattice-matched heterostructures in advanced devices.[33] These methods ensure the p-i-n junction's abrupt doping transitions, which are vital for efficient carrier collection. Metallization and passivation steps protect the device and optimize optical coupling. Ohmic contacts, typically formed using titanium-aluminum (Ti/Al) stacks for n-type regions, are evaporated or sputtered onto the semiconductor surface followed by annealing to achieve low-resistance interfaces without rectification.[34] Passivation layers, such as silicon dioxide (SiO₂), are then deposited via plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition to encapsulate the junction and prevent surface recombination, while anti-reflective coatings like SiO₂ or multilayer stacks reduce reflection losses at the light-entry surface, improving quantum efficiency by up to 20-30% in silicon photodiodes.[35] Packaging completes the fabrication by ensuring environmental stability and optical performance. Hermetic sealing, often in TO-can or ceramic packages, uses metal lids welded or soldered to the base to exclude moisture and contaminants, thereby enhancing long-term reliability in harsh conditions.[36] Integration with optics, such as aspheric lenses or windows, is incorporated during assembly to focus incident light onto the active area, minimizing divergence and maximizing coupling efficiency for applications like fiber-optic receivers.[37] Yield considerations in photodiode fabrication emphasize defect density control to achieve high uniformity across wafers. Techniques like gettering during epitaxial growth remove impurities, targeting defect densities below 10⁸ cm⁻², while CMOS-compatible processes enable scaling to large arrays by leveraging standard lithography and backend steps for monolithic integration. This compatibility supports fabrication yields exceeding 90% for focal plane arrays in imaging systems. Modern advances as of 2025 include wafer-scale integration of hybrid III-V on silicon platforms, where heterogeneous bonding transfers epitaxial III-V layers onto CMOS-processed silicon wafers, enabling compact, high-performance photodiodes for datacom with bandwidths over 100 GHz.[38] Additionally, 3D printing techniques have emerged for custom structures, such as facet-attached microlenses, allowing rapid prototyping and precise optical alignment in photonic integrated circuits.[39]Device Structures and Types

PIN Photodiode

The PIN photodiode features a layered structure consisting of a p-type semiconductor region, an intrinsic (undoped or lightly doped) semiconductor region, and an n-type semiconductor region, denoted as p-i-n.[40] The intrinsic region, typically several micrometers thick, separates the heavily doped p and n layers and expands significantly under reverse bias to form a wide depletion zone.[12] This design contrasts with standard p-n photodiodes by minimizing carrier diffusion and enhancing the electric field uniformity across the absorption area.[22] A primary advantage of the PIN structure is the reduced junction capacitance due to the extended depletion width, which lowers the RC time constant and improves high-frequency performance. The capacitance is approximated by the formula where is the permittivity of the semiconductor material, is the active area, is the intrinsic region width, and represents the depletion widths in the p and n regions (often negligible in heavily doped layers).[7] The wider depletion region also enables higher quantum efficiency across a broad spectral range from ultraviolet to infrared wavelengths, as more photogenerated carriers are collected before recombination.[4] Compared to p-n diodes, PIN photodiodes exhibit lower noise levels, primarily from reduced thermal noise associated with the lower capacitance and minimized dark current.[12] In operation, particularly in photoconductive mode under reverse bias, the strong electric field in the intrinsic region sweeps photogenerated electron-hole pairs toward the respective contacts with minimal recombination, enabling efficient carrier collection.[11] This configuration supports high-speed applications, with typical bandwidths ranging from 10 to 100 GHz depending on the intrinsic layer thickness and material.[41] PIN photodiodes are briefly referenced here for their enhanced performance in reverse-biased photoconductive operation, as detailed in broader mode discussions. Commonly employed in telecommunications receivers for optical signal detection, PIN photodiodes benefit from their balance of speed and sensitivity in fiber-optic systems.[22] However, they require higher reverse bias voltages—often tens of volts—to fully deplete the intrinsic region and achieve optimal performance, which can increase power consumption and circuit complexity.[42] Additionally, the multi-layer structure introduces greater fabrication challenges, including precise control of the intrinsic region's doping and thickness uniformity during epitaxial growth or diffusion processes.[43]Avalanche Photodiode

Avalanche photodiodes (APDs) are specialized photodiodes that achieve internal current gain through carrier multiplication, enabling enhanced sensitivity for low-light detection in optical systems. Unlike standard photodiodes, APDs operate under high reverse bias to trigger impact ionization, amplifying the photocurrent while introducing specific noise characteristics. This gain mechanism makes APDs particularly valuable for applications requiring high signal-to-noise ratios, such as fiber-optic communications and photon counting.[19][44] The structure of an APD typically incorporates a high-field multiplication region within a p-i-n configuration or utilizes separate absorption and multiplication layers to separate photon absorption from carrier multiplication, optimizing quantum efficiency and reducing noise. In the p-i-n based design, the intrinsic region is divided such that photogeneration occurs in a lower-field absorption zone, while multiplication happens in a narrower, high-field avalanche region under reverse bias exceeding 100 V. Separate absorption-multiplication structures, often denoted as SAM or SACM (separate absorption, charge, and multiplication), further enhance performance by tailoring material properties for specific wavelengths, such as InGaAs absorption layers paired with InP multiplication regions for near-infrared detection.[44][4][19] The gain in APDs arises from impact ionization, where photogenerated carriers gain sufficient kinetic energy in the high electric field to ionize additional atoms, creating secondary electron-hole pairs that further multiply. This process yields a multiplication gain , where is the output current and is the primary photocurrent, with typical values ranging from 100 to 1000 depending on bias and material. The total output current can be expressed as where accounts for thermally generated carriers. However, the stochastic nature of ionization leads to excess noise, quantified by the noise factor , with as the excess noise index (typically 0.2–0.8 for optimized designs), which degrades the signal-to-noise ratio at high gains.[45][46] APDs are classified by the initiating carrier and multiplication dynamics: electron-initiated types, common in InP-based devices, leverage higher electron ionization coefficients for lower noise, while hole-initiated variants in silicon exploit hole multiplication for visible-light applications. Reach-through APDs extend the depletion region to fully deplete the absorption layer, ensuring uniform field penetration and higher efficiency, whereas electron-hole APDs allow both carriers to contribute to multiplication, though this often increases noise due to mixed ionization rates. Silicon APDs favor electron initiation through doping profiles that prioritize electron avalanches, achieving gains up to 1000 with moderate noise.[47] Despite their advantages, APDs face limitations from excess noise, which scales with gain and limits usable to avoid signal degradation, as well as the risk of premature breakdown from field nonuniformities or defects. High operating voltages also necessitate precise bias control and often thermoelectric cooling to suppress thermal generation of dark current and maintain gain stability, particularly in arrays or high-temperature environments.[46][44] Advances through 2025 have focused on low-noise superlattice APDs, incorporating type-II superlattices like InGaAs/GaAsSb for absorption and AlGaAsSb for multiplication, achieving gains over 100 with excess noise factors below 2 and gain-quantum efficiency products exceeding 3500% at 2 μm wavelengths, ideal for quantum sensing in mid-infrared regimes.[48][49] In 2025, further advancements include digital alloy AlAsSb/GaAsSb APDs demonstrating low dark current and noise for optical communications, and thin absorber AlInAsSb SACM APDs with suppressed dark currents at 2 μm.[50][51] These structures mitigate noise via engineered band alignments that favor single-carrier multiplication, enabling single-photon-level detection with reduced cooling requirements.Performance Characteristics

Responsivity and Sensitivity

Responsivity is a fundamental performance metric for photodiodes, defined as the ratio of the generated photocurrent to the incident optical power , expressed as .[52] This yields units of amperes per watt (A/W), quantifying the device's efficiency in converting light to electrical signal. The responsivity is wavelength-dependent, , and follows the relation , where is the elementary charge, is the wavelength, is the quantum efficiency, is Planck's constant, and is the speed of light; this equation highlights the linear scaling with photon energy and efficiency.[52] Spectral response curves, plotting versus , typically peak near the material's bandgap and drop sharply beyond the cutoff wavelength, such as for silicon photodiodes where maximum responsivity occurs around 900 nm.[52] Quantum efficiency is a key factor in responsivity, representing the ratio of charge carriers collected to incident photons, often reaching 70-90% in optimized devices.[53] External quantum efficiency accounts for losses like surface reflection, while internal quantum efficiency excludes these, focusing on absorption and collection within the active region. Material selection influences , with silicon offering high values in the visible to near-infrared due to its 1.12 eV bandgap, though broader spectra require materials like InGaAs for extended response.[52] Sensitivity metrics extend beyond responsivity to characterize minimum detectable signals. The noise equivalent power (NEP) is the incident power yielding a signal-to-noise ratio of 1 in a 1 Hz bandwidth, typically in W/√Hz.[54] Specific detectivity , a normalized figure of merit, is given by , with units cm √Hz/W, where is the active area and is the bandwidth; higher indicates superior low-light performance, often exceeding 10^{12} cm √Hz/W for silicon photodiodes.[54] Responsivity and sensitivity are measured using calibrated monochromatic light sources, such as lasers or tunable lamps, to illuminate the device while monitoring photocurrent with a transimpedance amplifier under controlled bias.[24] Temperature affects these metrics, with responsivity varying with wavelength, typically decreasing by about 0.2-0.4% per °C in the visible and near-infrared regions due to bandgap widening, though it can be positive in the infrared.[55] Optimization strategies enhance performance, including anti-reflective (AR) coatings that minimize Fresnel losses to boost external up to 90% across target wavelengths.[57] Tailoring the absorption layer thickness and doping profiles further improves internal efficiency, while selecting materials matched to application wavelengths ensures peak responsivity, as in silicon for telecom bands near 850 nm.[58]Speed and Noise Considerations

The speed of a photodiode is fundamentally limited by two primary factors: the RC time constant associated with the device's capacitance and load resistance, and the carrier transit time across the depletion region. The rise time is approximated by , where is the load resistance and includes the junction capacitance and any parasitic capacitances, determining the temporal response in low-frequency applications. For high-speed operation, the bandwidth is further constrained by the carrier transit time , where is the depletion layer width and is the saturation velocity of charge carriers (typically around cm/s in silicon), as carriers must traverse the absorption region before collection.[59] These limits often result in 3 dB bandwidths ranging from GHz for optimized PIN structures to lower values in larger-area devices, with the junction capacitance scaling with active area and reverse bias reducing it by widening the depletion region.[25] Noise in photodiodes arises from multiple sources that degrade the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly in low-light or high-speed scenarios. Shot noise, originating from the discrete nature of photocurrent and dark current, has a root-mean-square (rms) value given by , where is the electron charge, is the total current, and is the bandwidth; this Poisson-limited noise dominates under illumination and sets the fundamental quantum limit for detection.[60] Thermal (Johnson) noise, due to random thermal motion of charge carriers, contributes an rms current of , with as Boltzmann's constant, the temperature, and the shunt or load resistance, becoming prominent in high-impedance circuits.[61] Additionally, 1/f (flicker) noise, which follows a power spectral density () at low frequencies, stems from surface traps and material defects in semiconductors like InGaAs, significantly impacting baseband signals below 1 kHz.[62] A key figure of merit for evaluating photodiode performance under noise constraints is the noise-equivalent bandwidth, which quantifies the effective frequency range where the integrated noise equals the shot noise in a 1 Hz band, guiding trade-offs such as increasing reverse bias to enhance speed (by reducing capacitance) at the cost of higher dark current and thus amplified shot noise.[25] For instance, higher bias voltages can achieve bandwidths exceeding 10 GHz but elevate thermal and shot noise densities, necessitating careful circuit design to maintain SNR above 20 dB in communication systems.[63] Mitigation strategies include reducing the active area to minimize junction capacitance (lowering RC limits and thermal noise) and employing transimpedance amplifiers (TIAs), which convert photocurrent to voltage with low-noise op-amps, achieving noise floors as low as 10 fA/√Hz while preserving bandwidth up to several GHz.[64][65] Recent advancements in 2D materials, such as graphene and black phosphorus integrated into photodiode structures, have pushed response speeds into the terahertz regime, with devices demonstrating responsivities over 5 A/W and response times below 2 μs at frequencies up to 0.29 THz, enabled by ultrafast carrier dynamics and reduced transit times in atomically thin layers.[66] These configurations offer a pathway to overcome traditional bandwidth-noise trade-offs, with NEP values as low as ~100 pW/√Hz at cryogenic temperatures for black phosphorus devices in the THz range, though challenges like 1/f noise from interfaces persist.[19]Effects and Phenomena

Desired Photodiode Effects

In photodiodes, photogeneration occurs when incident photons with energy greater than the semiconductor bandgap are absorbed, primarily in the depletion region, creating electron-hole pairs or excitons that contribute to the photocurrent. This process is most efficient in the intrinsic or lightly doped regions where the built-in electric field separates the carriers before recombination, enabling high quantum efficiency in reverse-biased operation.[67] Carrier collection in photodiodes relies on both drift and diffusion mechanisms, where the strong electric field in the depletion region accelerates minority carriers toward the contacts via drift, while diffusion aids in collecting carriers generated near the edges of the region. This field-assisted transport minimizes recombination losses, achieving quantum yields approaching unity and supporting fast response times in well-designed structures.[67] Wavelength selectivity in photodiodes arises from the material's bandgap, which determines the cutoff wavelength beyond which absorption is negligible, allowing tailored sensitivity to specific spectral ranges.[68] The relationship is given by the equation where is the bandgap energy, is Planck's constant, is the speed of light, and is the cutoff wavelength; for example, silicon photodiodes exhibit a sharp response drop around 1100 nm corresponding to eV.[68] This intrinsic filtering enhances applications requiring discrimination against longer wavelengths, such as in visible-light sensing. Non-avalanche photoconductive gain in certain photodiodes, particularly those with trap states, results from carrier trapping that prolongs the lifetime of one carrier type, allowing the other to recirculate and amplify the photocurrent beyond unity gain. In wide-bandgap semiconductors like β-Ga₂O₃ used in Schottky photodiodes, this trapping by self-trapped holes enables gains exceeding 50 while maintaining reasonable linearity, beneficial for low-light detection without high-voltage operation.[69] Thermal effects can positively influence photodiode stability through temperature-compensated bias designs, where controlled heating or circuit adjustments counteract variations in dark current and responsivity, ensuring consistent performance across operating ranges.Unwanted Photodiode Effects

One significant unwanted effect in photodiodes is dark current, which refers to the small electric current that flows through the device in the complete absence of incident light. This current arises primarily from thermal generation of electron-hole pairs within the semiconductor material, particularly in the depletion region and adjacent quasi-neutral regions. The magnitude of the dark current can be approximated by the formula , where is the elementary charge, is the intrinsic carrier concentration, is the junction area, and are the diffusion lengths for holes and electrons, and are the corresponding minority carrier lifetimes, and is the donor concentration on the n-side (assuming an asymmetric junction).[70] Dark current exhibits strong temperature dependence, typically doubling for every 10°C increase in temperature due to the exponential rise in intrinsic carrier concentration with thermal energy.[23] At high light intensities, photodiodes can experience saturation, where the output photocurrent no longer increases linearly with input optical power. This occurs due to gain compression mechanisms, such as space charge effects that slow carrier transport, and increased recombination losses in the active region, which reduce the collection efficiency of photogenerated carriers. In photodiode arrays, crosstalk represents another adverse effect, manifesting as unintended signal interference between adjacent elements. Optical crosstalk arises from light scattering or diffraction into neighboring pixels, while electrical crosstalk stems from capacitive coupling or substrate currents that propagate signals laterally through the shared semiconductor structure.[71] Photodiodes are also susceptible to aging and long-term degradation, which can compromise performance over time. Exposure to radiation, such as in space environments, induces defects in the crystal lattice that increase dark current and reduce responsivity; for instance, silicon-based devices show significant degradation after proton irradiation doses equivalent to years in low-Earth orbit.[72] Humidity accelerates degradation by promoting moisture ingress, leading to corrosion at contacts or passivation layers and elevated leakage currents. These factors contribute to a reduced mean time between failures (MTBF), often estimated using accelerated life testing models that account for environmental stressors to predict operational reliability. To mitigate these unwanted effects, several strategies are employed. Cooling the photodiode, such as through thermoelectric coolers, suppresses thermal generation and thus lowers dark current by factors of 10 or more per 30-50°C reduction.[73] Guard rings—doped regions surrounding the active junction—help alleviate edge effects by distributing the electric field more uniformly, preventing premature breakdown and reducing surface-related leakage currents.[74] For space applications, where radiation hardness is critical, gallium nitride (GaN)-based photodiodes offer superior tolerance; GaN's wide bandgap and defect-resistant structure provide better performance compared to silicon counterparts.[75]Applications

Optical Sensing and Communication

Photodiodes play a pivotal role in optical sensing and communication systems, where they convert incident light into electrical signals for high-fidelity data transmission and environmental monitoring. In fiber optic receivers, indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) PIN and avalanche photodiodes (APDs) are widely employed due to their sensitivity in the near-infrared range (900–1700 nm), enabling detection of modulated optical signals in telecommunications infrastructure. These devices support data rates from 10 Gbps to 400 Gbps in Ethernet applications, such as data center interconnects and long-haul networks, by providing low-noise amplification and high bandwidth exceeding 30 GHz. For instance, InGaAs APDs achieve a gain-bandwidth product of over 400 GHz, facilitating error-free operation in dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) systems. Bit error rates (BER) below 10^{-12} are routinely maintained through forward error correction (FEC) techniques, which correct pre-FEC BERs up to 10^{-3} by adding parity bits, ensuring reliable performance over distances exceeding 100 km without regeneration. In visible-range applications like barcode scanners and light detection and ranging (LIDAR) systems, silicon photodiodes dominate owing to their cost-effectiveness, fast response times (rise times under 1 ns), and broad sensitivity from 400 nm to 1100 nm. Barcode scanners utilize silicon PIN photodiodes to detect reflected laser pulses from bar patterns, converting intensity variations into electrical signals for decoding at speeds up to thousands of scans per second. In LIDAR, silicon APDs or PIN photodiodes enable pulse detection by measuring the time-of-flight of short laser pulses (typically 10–100 ns duration), achieving sub-millimeter resolution in automotive and surveying applications through precise timing of photon arrival. These photodiodes offer quantum efficiencies above 80% in the visible spectrum, minimizing crosstalk and enabling compact, low-power designs. Environmental sensing leverages specialized photodiodes for non-contact monitoring of atmospheric conditions. Gallium nitride (GaN) photodiodes excel in ultraviolet (UV) monitors, exhibiting solar-blind operation (cutoff below 365 nm) and high responsivity (up to 0.2 A/W at 254 nm), making them ideal for detecting ozone levels or solar UV index without interference from visible light. These devices operate in photovoltaic mode for low-power, real-time measurement in outdoor stations, with detectivities exceeding 10^{12} Jones for trace UV flux monitoring. For gas detection, photodiodes integrated into absorption spectroscopy systems quantify species like methane or CO2 by measuring light attenuation at specific wavelengths; silicon or InGaAs photodiodes paired with tunable diode lasers achieve parts-per-billion sensitivity through differential detection, reducing noise from ambient light. Integration of photodiodes with vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs) in optical transceivers enhances efficiency for short-reach links in 5G and emerging 6G networks. InGaAs or silicon photodiodes are co-packaged with 850 nm or 1310 nm VCSELs in pluggable modules (e.g., QSFP-DD), supporting bidirectional data rates up to 400 Gbps over multimode fiber with power consumption below 10 W per channel. In 5G fronthaul, these transceivers transport digitized radio signals between baseband units and remote radio heads, achieving latencies under 100 μs via time-division duplexing. For 6G prototypes, hybrid integration on silicon photonics platforms incorporates PIN photodiodes for analog fronthaul, enabling terabit-per-second aggregate capacity while meeting power-over-fiber requirements for remote units. A notable case study is the deployment of photodiodes in submarine fiber optic cables, which underpin over 99% of global internet traffic. At cable landing stations, high-sensitivity InGaAs APDs serve as receivers in terminal equipment, demodulating wavelength-multiplexed signals at rates up to 400 Gbps per channel across transoceanic spans exceeding 10,000 km. While modern repeaters primarily use erbium-doped fiber amplifiers (EDFAs) for all-optical regeneration every 50–80 km, legacy systems and monitoring nodes incorporate PIN/APD pairs for fault detection and performance verification, ensuring BER below 10^{-12} with FEC to support seamless intercontinental connectivity. This infrastructure, exemplified by systems like the MAREA cable (Microsoft/Facebook, 2018), relies on photodiode arrays for multiplexing up to 256 channels, facilitating petabit-scale throughput for cloud services and real-time applications.Imaging and Scientific Instrumentation

In imaging applications, complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) image sensors employ active pixel sensors (APS) that integrate photodiodes as the primary light-detecting elements, enabling compact and cost-effective designs for consumer cameras such as those in smartphones and digital cameras. Each pixel in a CMOS APS consists of a photodiode paired with one or more transistors for amplification and readout, allowing for on-chip signal processing that reduces the need for external circuitry and improves power efficiency compared to traditional charge-coupled devices (CCDs).[76][77] These sensors dominate consumer markets due to their ability to capture high-resolution images at video rates, with fill factors often exceeding 60% through microlens arrays that direct light onto the photodiode active area.[78] In scientific instrumentation, photodiode arrays play a crucial role in spectroscopy, particularly in monochromators where silicon (Si) and germanium (Ge) arrays enable precise material analysis across visible and infrared spectra. Si photodiode arrays detect wavelengths from ultraviolet to near-infrared (approximately 200–1100 nm), while Ge variants extend sensitivity into the mid-infrared (up to 1800 nm), facilitating applications like Raman spectroscopy and environmental monitoring by dispersing light through a monochromator and measuring intensity at multiple channels simultaneously.[79][80] These arrays provide high spatial resolution and low crosstalk, essential for resolving spectral lines in chemical composition studies, with quantum efficiencies often reaching 80–90% in optimized Si configurations.[81] Medical applications leverage photodiodes for non-invasive diagnostics, such as in pulse oximeters operating in transmission mode, where red and near-infrared light passes through tissue like a fingertip, and the transmitted intensity is detected by a photodiode to calculate blood oxygen saturation via the ratio of absorbed light at dual wavelengths (typically 660 nm and 940 nm).[82][83] In fluorescence microscopy, photodiodes, including avalanche variants, detect emitted light from fluorophores excited by lasers, enabling high-sensitivity imaging of cellular structures with sub-micron resolution; for instance, single-photon avalanche diodes (SPADs) integrated into arrays achieve picosecond timing for fluorescence lifetime measurements.[84][85] In particle physics, silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs)—compact arrays of avalanche photodiodes—serve as key detectors in experiments at CERN, such as the CMS upgrade at the Large Hadron Collider, where they couple to scintillating fibers or crystals to timestamp particle interactions with sub-nanosecond precision and detect low-light yields from high-energy collisions.[86][87] SiPMs offer photon detection efficiencies up to 50%, magnetic field insensitivity, and robustness in radiation environments, outperforming traditional photomultiplier tubes in calorimetry and tracking systems.[88][89] Recent advances as of 2025 include quantum dot-enhanced photodiodes for hyperspectral imaging, where colloidal quantum dots (e.g., lead-free InAs or HgTe variants) are integrated with Si substrates to extend spectral coverage into the shortwave infrared (up to 1700 nm) while maintaining CMOS compatibility, enabling single-pixel or array-based systems for material identification in remote sensing and biomedical analysis with resolutions exceeding 100 spectral bands.[90][91] Additionally, AI integration in photodiode instrumentation has emerged for real-time data processing, such as machine learning algorithms embedded in array readouts to enhance noise reduction and spectral unmixing in hyperspectral setups, addressing limitations in traditional processing pipelines.[92][93]Advanced Configurations

Photodiode Arrays

Photodiode arrays integrate multiple photodiodes into structured arrangements to enable parallel light detection across spatial dimensions, facilitating applications such as scanning and imaging. Linear one-dimensional (1D) arrays typically consist of 512 to 1024 silicon photodiodes, each approximately 25 μm wide and 2 mm high, arranged in a row for tasks like spectrophotometry where spectral dispersion is captured along a single axis.[94][95] Two-dimensional (2D) arrays expand this to grids with M rows and N columns, often using charge-coupled device (CCD) or complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) architectures to form imaging planes in cameras, where horizontally oriented CCD lines or pixel matrices collect light for full-frame capture.[96][97] Readout mechanisms in photodiode arrays vary by architecture to transfer accumulated charge efficiently. In CCD-based arrays, charge is serially shifted through the array via coupled gates, enabling low-noise transfer but requiring global clocking that can limit speed in large formats.[98] In contrast, CMOS active pixel sensor (APS) arrays incorporate amplifiers and addressing circuitry at each pixel, allowing random access readout for higher speed and integration of on-chip processing, though with potentially higher noise from transistor variability.[77][99] Passive-pixel sensors (PPS), an earlier CMOS variant, rely on shared column gates for readout, offering simpler fabrication but suffering from higher fixed-pattern noise compared to APS due to the lack of per-pixel amplification.[100] Scalability of photodiode arrays has advanced to support resolutions exceeding 100 megapixels in CMOS implementations, driven by shrinking pixel pitches down to 2-4 μm while maintaining performance.[101] Fill factors, the ratio of active light-sensitive area to total pixel area, routinely surpass 90% through the integration of microlens arrays that focus incident light onto the photodiode, minimizing losses from surrounding circuitry.[102] This enhancement is particularly critical in APS designs where transistor overhead reduces intrinsic photosensitive area. Key challenges in photodiode arrays include achieving uniformity across elements and preventing blooming. Pixel-to-pixel gain variations are typically held below 10% in CCD arrays through precise fabrication, but CMOS APS can exhibit higher fixed-pattern noise from threshold mismatches, necessitating calibration techniques like correlated double sampling.[103] Blooming, the overflow of excess charge into adjacent pixels during high illumination, is mitigated by anti-blooming gates or vertical overflow drains in CCD structures, limiting spillover to neighboring diodes and preserving image fidelity.[104][105] Recent advances through 2025 have focused on stacked architectures and back-side illumination (BSI) to overcome traditional limitations. Three-wafer stacked CMOS sensors with BSI photodiodes enable global shutter operation by separating charge collection from readout circuitry, achieving shutter efficiencies over 99.9% without rolling artifacts in high-speed imaging.[106] BSI configurations illuminate the photodiode from the backside, bypassing front-side wiring shadows to boost quantum efficiency (QE) to above 90% in the visible spectrum, particularly for small pixels in megapixel arrays.[107] These innovations, including 2.2 μm pixel stacked BSI global shutter sensors, support compact, high-dynamic-range modules for demanding environments like machine vision.[108]Pinned Photodiode

The pinned photodiode (PPD) is a buried photodiode structure essential to modern charge-coupled device (CCD) and complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) image sensors, featuring a p⁺/n/p configuration that pins the surface potential to minimize noise and defects.[109] The n-type region serves as the charge collection volume within a p-type epitaxial layer or substrate, while the shallow p⁺ pinning layer at the surface accumulates holes to prevent depletion and isolate the active area from interface traps at the silicon-oxide boundary.[110] This design enables efficient photoelectron accumulation and transfer, distinguishing it from simpler p-n junction photodiodes.[111] Developed in the early 1980s by Nobukazu Teranishi and colleagues at NEC Corporation, the PPD was initially introduced for interline-transfer CCDs to suppress vertical smear and reduce dark current generation, marking a pivotal advancement over surface-channel photodiodes.[18] Its adaptation to CMOS active pixel sensors in the mid-1990s, led by Eric Fossum at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, revolutionized consumer and scientific imaging by integrating low-noise detection with on-chip amplification.[109] The structure's physics relies on the pinned potential maintaining a stable electric field, which confines photogenerated electrons in the n-well during exposure while allowing complete depletion for charge transfer.[112] In typical operation within a four-transistor (4T) CMOS pixel, the PPD integrates photocharge under reverse bias from the substrate contact, with electrons collected in the n-region potential pocket as light absorption creates electron-hole pairs—holes drifting to the p-substrate and electrons to the n-buried layer.[111] Readout involves pulsing the n⁺-implanted transfer gate to form a channel under the gate oxide, rapidly transferring the charge packet to an adjacent floating diffusion node without residual lag, followed by source-follower buffering and correlated double sampling to subtract reset noise.[110] The pinning layer's hole accumulation suppresses trap-assisted generation, yielding dark current densities as low as 0.1–1 e⁻/pixel/s at room temperature in optimized processes.[112] Key advantages include near-complete charge transfer efficiency (>99.99%), eliminating image lag seen in partially depleted diodes, and inherently low read noise (down to sub-electron levels with CDS), which supports high dynamic range exceeding 70 dB in back-illuminated implementations.[109] The shallow p⁺ layer enhances blue-light sensitivity by reducing absorption losses near the surface, while compatibility with standard CMOS fabrication enables cost-effective scaling to megapixel arrays.[110] Limitations involve potential pinning voltage variability affecting full well capacity (typically 10,000–50,000 electrons), addressed in advanced variants through epitaxial thickness optimization.[111] Recent innovations extend PPDs to non-traditional substrates, such as thin-film polycrystalline silicon on glass, where a stacked p⁺/i/n/p structure preserves pinning benefits for flexible sensors, achieving conversion gains of 50–100 μV/e⁻ and dark currents below 10 fA/cm² while enabling full charge transfer for noise suppression.[113] Fully depleted PPDs, biased via substrate reverse voltage in high-resistivity silicon, further improve near-infrared quantum efficiency (>80%) and crosstalk reduction in time-of-flight applications.[114] These configurations underscore the PPD's enduring impact, powering over 90% of commercial image sensors as of 2020.[109]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/figure/Temperature-coefficient-of-silicon-photodiode-photosensitivity-given-by-UDT-Sensors-Inc_fig12_332422592