Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

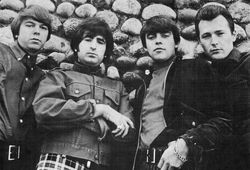

The Standells

View on Wikipedia

The Standells are an American garage rock band from Los Angeles, California, formed in the 1960s, who have been referred to as a "punk band of the 1960s", and are said to have inspired such groups as the Sex Pistols and Ramones.[1] They recorded the 1966 hit "Dirty Water", written by their producer, Ed Cobb. (Ed Cobb also wrote "Tainted Love", a Gloria Jones song which became world famous when Soft Cell covered it.) "Dirty Water" is the anthem of several Boston sports teams and is played following every Boston Red Sox and Boston Bruins home win.

Key Information

History

[edit]Formation

[edit]The Standells band was formed in 1962 by lead vocalist and keyboard player Larry Tamblyn (born Lawrence Arnold Tamblyn; February 5, 1943 – March 21, 2025),[2] guitarist Tony Valentino (born Emilio Bellissimo, May 24, 1941),[2] bass guitarist Jody Rich, and drummer Benny King (aka Hernandez).[3] Tamblyn had previously been a solo performer, recording several 45 singles in the late 1950s and early 1960s including "Dearest", "Patty Ann", "This Is The Night", "My Bride To Be" and "Destiny" for Faro and Linda Records. He was the brother of actor Russ Tamblyn and the uncle of actor Amber Tamblyn.

The Standells band name was created by Larry Tamblyn,[4] derived from standing around booking agents' offices trying to get work.[2] In early 1962, drummer Benny King joined the group, and as "the Standels", their first major performance was in Honolulu at the Oasis Club. After several months, Rich and King departed. Tamblyn then assumed leadership of the group. He and Valentino re-formed the Standels, adding bass guitarist Gary Lane (September 18, 1938 – November 5, 2014)[5] and drummer Gary Leeds, later known as Gary Walker of The Walker Brothers. Later that year, the band lengthened its name to "Larry Tamblyn & the Standels". In 1963 an extra "L" was added, and as "Larry Tamblyn and the Standells" the group made its first recording "You'll Be Mine Someday/Girl In My Heart" for Linda Records (released in 1964).[6] In the latter part of the year, the band permanently shortened its name to "The Standells".[2] After the Standells signed with Liberty in 1964, Leeds left the group, and was replaced by lead vocalist and drummer Dick Dodd.[7] Dodd was a former Mouseketeer[8] who had been the original drummer for The Bel-Airs, known for the surf rock song "Mr. Moto", and eventually became the singer who sang lead on all of the Standells hit songs.

First album

[edit]In 1964, Liberty Records released three Standells singles and an album, The Standells in Person at P.J.s. The album was later re-issued as The Standells Live and Out of Sight. The band also appeared on The Munsters TV show, as themselves in the episode "Far Out Munsters," performing "Come On and Ringo" and a version of The Beatles' "I Want to Hold Your Hand".[9] In late 1964, they signed with Vee Jay and released two singles in 1965. Later in the year they signed with MGM for one single.

The group appeared in several low-budget films of the 1960s, including Get Yourself a College Girl (1964) and cult classic Riot on Sunset Strip (1967). The Standells performed incidental music in the 1963 Connie Francis movie Follow the Boys, which coincidentally co-starred Larry Tamblyn's brother, Russ Tamblyn. The Standells played the part of the fictional rock group the "Love Bugs" on the television sitcom Bing Crosby Show in the January 18, 1965, episode "Bugged by the Love Bugs". In addition to appearing in the aforementioned The Munsters episode as themselves, they also appeared performing an instrumental in the background in the March 29, 1965 Ben Casey series episode, "Three 'Lil Lambs." The band also performed the title song for the 1965 children's movie, Zebra in the Kitchen.

Some reports state that early versions of the band had a relatively clean image and performed only cover songs.[9] However, early 1964 photos counter that notion, showing the Standells with long hair, making them one of the first American rock groups to adopt that style. In order to work in conservative nightclubs like P.J.'s, the group members were forced to cut their shaggy locks.[10] Like the Beatles, early rock groups did mostly cover songs in nightclubs.

Dirty Water

[edit]In 1965, the group – Dodd, Tamblyn, Valentino and Lane – signed with Capitol Records' label Tower, teaming up with producer Ed Cobb. Cobb wrote the group's most popular song, "Dirty Water", which the band recorded in late 1965. The song's references to the city of Boston are owed to Cobb's experiences with a mugger in Boston. The song also makes reference to the Boston Strangler and the dorm curfews for college women in those days.[11]

"Dirty Water" reached No. 11 on the Billboard charts on July 9 - 16, 1966, No. 8 on the Cashbox charts on July 9 - 16, 1966, and No. 1 on the Record World charts. "Dirty Water" was on the WLS playlist for eighteen total weeks, just ahead of "California Dreamin'" by a week, for most weeks on that playlist during the 1960s. Though the song is credited solely to Cobb, band members Dodd, Valentino and Tamblyn have claimed substantial material-of-fact song composition copyright contributions to it as well as contributing to its arrangement.[12] Tamblyn has stated that Cobb's version was a "standard blues song", adding: "We took the song with the condition that we could arrange in any way we want; we added the guitar riff into it and all of the wonderful vocal asides like, 'I'm gonna tell you a story, It's all about my town, I'm going to tell you a big fat story'...that was all written by us."[12]

According to critic Richie Unterberger,

"Dirty Water" [was] an archetypal garage rock hit with its Stones-ish riff, lecherous vocal, and combination of raunchy guitar and organ. While they never again reached the Top 40, they cut a number of strong, similar tunes in the 1966–1967 era that have belatedly been recognized as 1960s punk classics. "Garage rock" may not have been a really accurate term for them in the first place, as the production on their best material was full and polished, with some imaginative touches of period psychedelia and pop.[9]

"Dirty Water" is listed in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's "500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll."[13]

Dodd briefly left the Standells in early 1966, and was replaced by Dewey Martin, who became a member of Buffalo Springfield. Dodd returned to the group a few months later, as the "Dirty Water" song began to climb the charts.[10] The band recorded additional songs for their first full studio album Dirty Water in April 1966. Another popular track on the album was "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White", which would later be recorded by Washington, D.C. hardcore band Minor Threat, New York City punk band The Cramps, and Swedish garage band The Nomads.

Second and subsequent albums

[edit]The follow-up studio album, Why Pick on Me — Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White, was released in November 1966 and included the single "Why Pick on Me", which peaked at No. 54 on the Billboard chart. Gary Lane left the Standells in 1966, and was replaced by bass guitarist Dave Burke. John Fleck (born John William Fleckenstein; in Los Angeles, August 2, 1946 – October 18, 2017),[14][15] formerly of Love, soon replaced Burke in early 1967. The band then released their third album, The Hot Ones! In early 1967. It was simply a selection of popular songs that they covered. The band's fourth studio album, Try It, released in October 1967, contained the song "Riot on Sunset Strip", which had been released earlier in 1967 to support the soundtrack for the movie of the same name. The title track "Try It" was later recorded by Ohio Express and Cobra Killer. Picked by Billboard magazine to be the Standells' next hit, "Try It" was banned by Texas radio mogul Gordon McLendon, who deemed the record to have sexually suggestive lyrics.[16] The Standells were asked by Art Linkletter to debate with McLendon on his House Party TV show in 1967. By most accounts, McLendon was handily defeated,[4][17] but, by then, most radio stations had followed McLendon's lead and would not play the record. A third single released from this album, "Can't Help But Love You", would be the Standells last entry into the Billboard Hot 100, reaching No. 78, while also peaking at No. 9 in the Cashbox charts.

In 1968, Dick Dodd left the band to pursue a solo career. The Standells continued to perform with a varying line-up thereafter, briefly including guitarist Lowell George who went on to play with Little Feat.[9]

Later reformations and versions of the band

[edit]

In the 1980s, Dodd, Tamblyn and Valentino performed at a few shows with The Fleshtones. In 1984 the Standells played at the Club Lingerie on Sunset in Los Angeles and did some casino shows in Reno, Nevada. In the late 1980s, the Standells, with Tamblyn and Valentino, recorded and released an independent single featuring Tamblyn singing "60's Band"[2] In 1999, the Standells, featuring Dodd, Valentino and Tamblyn, along with bass player Peter Stuart,[18] appeared at the Cavestomp festival in New York, and their performance was subsequently released as an album called Ban THIS! As the title suggests, the Standells were thumbing their noses at McLendon. In 2000, bassist Gary Lane re-joined the Standells to perform at Las Vegas Grind. Between 2004 and 2007 the band was called upon to reform to make several appearances at major Boston sporting events. In 2006 the band sued Anheuser Busch for over $1 million after the company used "Dirty Water" in sports-related beer commercials without permission.[19]

After a show at the Cannery Casino and Hotel in Las Vegas in May 2009, The Standells reformed with Tamblyn and former bassist John Fleck, along with guitarist Paul Downing and veteran drummer Greg Burnham. The group went on to make appearances at Los Angeles venues Amoeba Records, Echoplex and the Whisky a Go Go. In 2010 they toured in Europe, performing in several countries, including their first ever UK show at 229 The Venue in London on June 19, 2010. In late 2010, Downing was replaced by guitarist Adam Marsland. In 2011, the band decided to record their first new album in over 40 years. Through Kickstarter, the Standells raised money towards the cost of the album.[20] Marsland left the group shortly thereafter. He was replaced by singer/guitarist Mark Adrian, a former member of the rock group Artica. In March 2012, the Standells performed at the SXSW Festival.[21]

In September 2012, Dick Dodd briefly rejoined the group, and they appeared at the Monterey Summer of Love "45 Years On" Festival that month.[22][23][24] On August 9, 2013, they released a new album, Bump, on GRA Records.[25] Dodd did not participate in the album. In June, Dodd again departed from the Standells for personal reasons. The group (without Dodd) headlined at the Satellite Club in Los Angeles, California, August 9,[26] the Adams Ave. St. Fair, San Diego, California on September 28,[26] and at the Ponderosa Stomp in New Orleans, Louisiana, October 5, 2013.[27]

Dick Dodd died of cancer on November 29, 2013.[28]

The Standells completed an extensive national tour from April 27 through May 21, 2014. It was their first major U.S. tour since the 1960s.[29] The group performed in Parma, Italy, on July 5 for the Festival Beat, and returned to California for the Tiki Oasis on August 17, 2014.[30]

Former band member, Gary Lane (Gary McMillan) died on November 5, 2014, from lung cancer aged 76.[31]

John "Fleck" Fleckenstein died October 18, 2017, of complications of AML Leukemia.[32] He was also a noted cinematographer.[33]

On October 22, 2022, the Standells biography From Squeaky Clean to Dirty Water, written by Larry Tamblyn, was published by Bear Manor Media. On December 23, 2023, Larry Tamblyn was inducted into the California Music Hall of Fame, introduced and officially inducted by his brother, actor Russ Tamblyn.

Larry Tamblyn died on March 21, 2025, at age 82.[34]

Boston connection

[edit]Despite the references to Boston and the Charles River in "Dirty Water," the Standells are not from Massachusetts. Tower Records producer Ed Cobb wrote the song after a visit to Boston, during which he was robbed on a bridge over the Charles River. None of the Standells had been to Boston before the song was released.[35]

In 1997, "Dirty Water" was decreed the "official victory anthem" of the Red Sox, and is played after every home victory won by the Boston Red Sox.[35] Also, in 1997 two Boston area music-related chain stores celebrated their joint 25th anniversary by assembling over 1500 guitarists, plus a handful of singers and drummers, to perform "Dirty Water" for over 76 minutes at the Hatch Shell adjacent to the Charles River.[36] At short notice, at the invitation of the Red Sox, The Standells played "Dirty Water" before the second game of the 2004 World Series at Fenway Park.[37] The band played at Fenway Park again in 2005 and 2006. In 2007, the Standells performed the national anthem at the first game of the 2007 American League Division Series, also at Fenway Park;[38] the Red Sox swept the Division Series and later the 2007 World Series.

In 2007, "Dirty Water, as sung by the Standells" was honored by official decree of The Massachusetts General Court. The song is now played not only at Red Sox games, but also those of the Boston Celtics, the Boston Bruins, and the Northeastern Huskies' hockey games. A book Love That Dirty Water: The Standells and the Improbable Red Sox Victory Anthem was published.[39]

In April 2019, Liverpool F.C., a club in the English Premier League, began playing "Dirty Water" after home matches, due to the fact that the club is owned by Fenway Sports Group, the same owners as the Boston Red Sox.[40][41]

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]| Year | Album details | Peak chart positions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| US |

US C/B | ||

| 1966 | Dirty Water

|

52 | 39 |

Why Pick on Me — Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White

|

— | — | |

| 1967 | The Hot Ones!

|

— | — |

Try It

|

— | — | |

| 2013 | Bump

|

— | — |

| "—" denotes a release that did not chart. | |||

Live albums

[edit]| Year | Album details |

|---|---|

| 1964 | The Standells in Person at P.J.s.

|

| 1966 | "Live" and Out of Sight

|

| 2000 | Ban This!

|

| 2001 | The Live Ones

|

| 2015 | Live on Tour - 1966

|

Compilation albums

[edit]| Year | Album details |

|---|---|

| 1983 | The Best of the Standells

|

| 1984 | Rarities

|

| 1998 | The Very Best of the Standells

|

| 1993 | Hot Hits & Hot Ones - Is This the Way You Get Your High?

|

Singles

[edit]| Year | Title (A-side, B-side) Both sides from same album except where indicated |

Label | Peak chart positions | Album | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [43] |

US C/B |

CAN RPM | ||||

| 1963 | "You'll Be Mine Someday" (Larry Tamblyn and the Standels) b/w "The Girl in My Heart" |

Linda (112) | — | — | — | Non-album tracks |

| 1964 | "The Shake" b/w "Peppermint Beatle” |

Liberty (55680) | — | — | — | "Live" and Out of Sight |

| "Help Yourself" b/w "I'll Go Crazy" |

Liberty (55722) | — | — | — | In Person at P.J.s | |

| "Linda Lou" b/w "So Fine |

Liberty (55743) | — | — | — | ||

| 1965 | "The Boy Next Door" b/w "B.J. Quetzal |

Vee-Jay (VJ 643) | 102 | — | — | Non-album tracks |

| "Don't Say Goodbye" b/w "Big Boss Man" |

Vee-Jay (VJ 679) | — | — | — | ||

| "Zebra in the Kitchen" b/w "Someday You'll Cry" |

MGM Records (K 13350) | — | — | — | ||

| "Dirty Water" b/w "Rari" |

Tower (185) | 11 | 8 | 11 | Dirty Water | |

| 1966 | "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White" b/w "Why Did You Hurt Me" |

Tower (257) | 43 | 59 | 21 | |

| "Ooh Poo Pah Doo" b/w "Help Yourself" | Sunset (61000) | — | — | — | In Person at P.J.s | |

| "Why Pick On Me" b/w 'Mr. Nobody |

Tower (282) | 54 | 68 | 34 | Why Pick on Me – Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White | |

| 1967 | "Don't Tell Me What to Do" (as "The Sllednats") b/w "When I Was a Cowboy" |

Tower (312) | — | — | — | Non-album tracks |

| "Riot on Sunset Strip" b/w "Black Hearted Woman" (from Why Pick on Me) |

Tower (314) | 133 | — | — | Riot on Sunset Strip soundtrack / Try It | |

| "Try It" b/w "Poor Shell of a Man" |

Tower (310) | — | — | — | Try It | |

| "Can't Help But Love You" b/w "Ninety-Nine and A Half" |

Tower (348) | 78 | 9 | — | ||

| 1968 | "Animal Girl" b/w "Soul Drippin'" |

Tower (398) | — | — | — | Non-album tracks |

| 1986 | "60's Band" b/w "Try It II" | Telco (101) | — | — | — | |

| "—" denotes a release that did not chart. | ||||||

References

[edit]- ^ "The Standells @ pHinnWeb". Phinnweb.org. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Burgess, Chuck (2007). Love That Dirty Water! The Standells and an Improbable Red Sox Victory Anthem. Rounder Books. ISBN 978-1-57940-146-7.

- ^ Hans Kesteloo. "Beyond The Beat Generation – The Standells Interview". Home.uni-one.nl. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Pore-Lee-Dunn Productions. "The Standells". Classicbands.com. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ "Passings: Gary (Lane) McMillan, Bass Player for the Standells (1938 - 2014)". VVN Music. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- ^ Joyson, Vernon (1998). Fuzz Acid & Flowers. Borderline Productions. ISBN 978-1899855063.

- ^ Dick Dodd at Charlie Gillett.com. Some sources give a date of October 25, and/or a birth year of 1943.

- ^ "Dickie Dodd (Oct 27, 1945)". The Original Mickey Mouse Club Show. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "The Standells | Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Nick Warburton (September 5, 2010). "The Standells". Garage Hangover. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ O'Nan, Stewart, and Stephen King. Faithful: Two Diehard Boston Red Sox Fans Chronicle the Historic 2004 Season. (Note that this book incorrectly refers to The Standells as a Boston proto-punk group, rather than a California garage band.)

- ^ a b "Gary James' Interview With Larry Tamblyn Of The Standells". classicbands.com. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ "Experience The Music: One Hit Wonders and The Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll | The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum". Rockhall.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "John Fleckenstein". IMDb.com. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ "Daniel Coston". Facebook.com.

- ^ [1] Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Standells". garage hangover. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Buckley, Peter (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock – Google Books. Rough Guides. p. 1001. ISBN 9781843531050. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Andrew Ryan (June 12, 2006). "Standells rock group says Budweiser plays 'Dirty'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Garage/Punk Legends, The Standells, to Record New Album by The Standells – Kickstarter". Kickstarter.com. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ "Standells". Schedule.sxsw.com. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "The Standells – index". Summer67.com. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "Dick Dodd Joins The Standells". Standells.wix.com. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "Standells". Facebook. Retrieved September 23, 2012.

- ^ "Standells Record Release Party & Concert". Last.fm. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ a b "The Satellite-live music venue in Los Angeles » The Blackeyed Soul Club presents a rare performance with The Standells with special guest Johnny Echols of Love – Tickets – The Satellite – Los Angeles, CA – August 9th, 2013". Thesatellitela.com. August 9, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ "Ponderosa Stomp announces lineup for 2013 concert, at Rock n'Bowl Oct. 3-5". NOLA.com. March 11, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Lee, Chris (November 30, 2013). "Dick Dodd dies at 68; Mouseketeer and musician". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ^ "Standells USA Tour". Standells.wix.com. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Standells EPK". Standells-official.com. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Dead Rock Stars Club : 2014 July To December". Thedeadrockstarsclub.com. Retrieved November 9, 2014.

- ^ Larry Tamblyn Facebook page Retrieved 2017-10-23

- ^ IMDB page for John Fleckenstein Retrieved 2017-10-23

- ^ Brodsky, Greg (March 2025). "Larry Tamblyn, Founder of The Standells ('Dirty Water'), Dies". Best Classic Bands. Archived from the original on March 21, 2025. Retrieved March 21, 2025.

- ^ a b "Red Sox Fans Love Their Dirty Water". Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Larry Katz (September 10, 1997). "Mass. entrepreneurs banking on world record down by the River Charles; Love that 'Dirty Water'". Boston Herald. Retrieved August 15, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Bill Plaschke (October 31, 2004). "Coming Through With the Big Hit at Fenway – Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Dan Shaughnessy (October 3, 2007). "Beckett pumps up Boston – Sparkling shutout gives Sox a big first step in playoffs". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Burgess, Chuck; Nowlin, Bill (2007). Love That Dirty Water: The Standells and the Improbable Red Sox Victory Anthem. Rounder Books. ISBN 9781579401467.

- ^ Henry, Linda Pizzuti (April 13, 2014). "Thanks for playing "Dirty Water" by the Standells after the win today! Fun touch!pic.twitter.com/Uhedda0fPa". @linda_pizzuti. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Explained: Why you hear the same song after every Anfield win". Liverpool FC. March 31, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ Burgess, Charles D.; Nowlin, Bill; Cobb, Ed (2007). Love That Dirty Water: The Standells and the Improbable Red Sox Victory Anthem. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books. ISBN 978-1-57940-146-7 – via the Internet Archive.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2003). Top Pop Singles 1955–2002 (1st ed.). Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. p. 671. ISBN 0-89820-155-1.

External links

[edit]The Standells

View on GrokipediaHistory

Formation and early years (1962–1963)

The Standells were formed in 1962 in Los Angeles by keyboardist and lead vocalist Larry Tamblyn, guitarist Tony Valentino, bassist Jody Rich, and drummer Benny King.[5] Tamblyn, born February 5, 1943, in Inglewood, California, drew on his family's Hollywood ties—his brother was actor Russ Tamblyn, known for roles in West Side Story—to help establish early connections in the entertainment industry.[4][5] The band named themselves "The Standells" after frequently standing around while waiting at booking agents' offices during auditions.[4] In their initial phase, the group operated as a cover band focused on R&B and surf music, performing at local high school dances and Los Angeles-area clubs.[6] Their first major engagement came in 1962 with a multi-month residency at the Oasis Club in Honolulu, Hawaii, followed by a gig at the Club Esquire in Eureka, California, in January 1963.[5] As the British Invasion took hold in late 1963, the Standells transitioned from a clean-cut, surf-oriented image to a rougher rock aesthetic, drawing inspiration from bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.[4][6] This evolution positioned them for broader appeal in the evolving garage rock scene, though they remained active in local performances during this formative period.[5]Initial recordings and lineup changes (1964–1965)

In early 1964, the Standells signed a recording contract with Liberty Records after submitting demo tapes that caught the attention of label executives, marking their entry into the major label scene following earlier independent releases. This deal facilitated their first significant output, including a series of singles and a live album captured during performances at the popular Hollywood nightclub P.J.'s. The band's evolving personnel during this period reflected the fluid nature of early garage rock groups, as they navigated club circuits and studio opportunities while refining their high-energy R&B-influenced sound.[5] The debut album, In Person at P.J.'s, was released in September 1964 on Liberty Records (LRP-3384), featuring live recordings of cover songs that showcased their raw, energetic style drawn from R&B and British Invasion hits. Tracks included "Help Yourself," "So Fine" (a cover of The Fiestas' doo-wop classic), "You Can't Do That" by The Beatles, "Money (That's What I Want)" by Barrett Strong, "Bony Moronie" by Larry Williams, and "Ooh Poo Pah Doo" by Jessie Hill, emphasizing their role as a dynamic live act rather than originators of material at this stage. The album, produced without overdubs to preserve the club's atmosphere, highlighted keyboardist Larry Tamblyn's lead vocals and organ work alongside guitarist Tony Valentino's riffing, though it received limited commercial attention and did not chart.[7][5] Lineup instability persisted into mid-1964, with original drummer Gary Leeds departing in May to pursue opportunities with Johnny Rivers and later co-founding The Walker Brothers, prompting the addition of Dick Dodd as his replacement. Dodd, born August 14, 1945, in Los Angeles and a former Mouseketeer from The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–1958), brought vocal versatility and showmanship to the drums, contributing backing and occasional lead vocals. Bassist Gary Lane, who had joined in late 1962 replacing founding member Jody Rich, remained a steady presence, helping solidify the core quartet of Tamblyn, Valentino, Lane, and Dodd by the end of the year—this configuration would underpin their shift toward greater prominence.[5][8] The band's early Liberty singles, such as "I'll Go Crazy" b/w "Love Is All I Have" (July 1964, Liberty 55709) and "So Fine" b/w "Big Brother" (October 1964, Liberty 55800), failed to chart but demonstrated their growing confidence in adapting covers for a rock audience. In late 1964, they briefly signed with Vee-Jay Records, releasing "The Boy Next Door" b/w "B.J. Quetzal" (VJ 643), which bubbled under at #102 on the Billboard Hot 100 in early 1965. Additional work included contributing "Bony Moronie" and "The Swim" to the soundtrack of the MGM film Get Yourself a College Girl (released December 1964), signaling an initial foray into original-leaning material and media tie-ins that foreshadowed their evolution beyond covers. By late 1965, after a short stint with MGM for the single "Zebra in the Kitchen," they transitioned to Capitol's Tower subsidiary, where producer Ed Cobb would guide their breakthrough.[5][9][10]Breakthrough with "Dirty Water" (1966)

In 1966, producer Ed Cobb penned "Dirty Water" after a personal encounter in Boston, where he was mugged near the notoriously polluted Charles River, inspiring lyrics that mockingly celebrated the city's underbelly of industrial waste, crime, and social frustrations.[11][12] The Standells, featuring their lineup of vocalist/keyboardist Larry Tamblyn, guitarist Tony Valentino, bassist Gary Lane, and drummer Dick Dodd, recorded the single in Los Angeles at Western Recorders, delivering it with a raw, aggressive garage rock edge—marked by snarling vocals, a gritty organ riff, and pounding rhythm that captured the era's youthful rebellion.[13][14][15] Issued as a single on Tower Records in May 1966, "Dirty Water" defied expectations by peaking at No. 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, even as some radio stations banned it for lyrics deemed too suggestive, including references to "lovers, muggers, and thieves" and "frustrated women" bound by dorm curfews.[6][16] The track's success marked the band's commercial breakthrough, propelling them into national tours across the U.S. and high-profile television appearances that amplified their notoriety. Media coverage hailed the Standells as early proto-punk innovators, praising the song's unpolished aggression and anti-establishment vibe as a departure from polished pop.[17][18] The full-length album Dirty Water, released on Tower in 1966, capitalized on the single's momentum and peaked at No. 52 on the Billboard 200, showcasing the band's high-octane sound through tracks like the snarling title song and "Medusa," which exemplified their gritty energy and thematic edge.[16][19] In Boston, where the song's subject matter hit close to home, audiences embraced "Dirty Water" during the Standells' live shows that year, chanting along and cementing its role as an impromptu local anthem amid the city's infatuation with its grimy charm.[20]Later albums and commercial decline (1967–1968)

Following the success of "Dirty Water," the Standells released their third studio album, Try It, in October 1967 on Tower Records, incorporating psychedelic influences into their raw garage rock style with tracks like "All Fall Down" and a cover of "St. James Infirmary."[21] The album's title track, issued as a single alongside "Poor Shell of a Man," faced widespread radio bans due to its perceived suggestive lyrics about drug use and promiscuity, severely limiting airplay and chart performance.[22] In May 1966, bassist Gary Lane departed during the band's first major concert tour, reportedly due to personal challenges, and was temporarily replaced by Dave Burke; John Fleckenstein (later known as John Fleck), who had previously played with the band Love, joined as bassist in November 1966.[5] Fleckenstein contributed to the band's sound on subsequent recordings, including co-writing efforts, but the lineup change coincided with growing internal tensions.[23] The band's final Tower single, "Animal Girl" b/w "Soul Drippin'," arrived in early 1968 but failed to chart, reflecting diminished commercial momentum.[9] Tower's inadequate promotion and failure to counter the radio bans exemplified label mismanagement, while the broader rock landscape shifted toward full-fledged psychedelia, marginalizing the Standells' aggressive garage aesthetic.[24] These factors, compounded by escalating drug use among members that strained band dynamics, led to declining sales and fewer opportunities.[17] Despite the setbacks, the Standells maintained a rigorous touring schedule through 1968, performing at venues like the Fillmore Auditorium and supporting acts such as The Doors, but these efforts could not reverse their fading visibility, marking the close of their most active 1960s phase.[5]Disbandment and hiatus (1969–1999)

Post-1968 activities and solo endeavors

Following the release of their final album in 1968, the Standells effectively disbanded in 1969 amid lineup changes and a departure from their longtime manager Ed Cobb.[5] Keyboardist and co-founder Larry Tamblyn transitioned to solo endeavors shortly after, releasing the single "Summer Clothes" on the Sunburst label in 1969.[5] In the early 1980s, he produced a children's album that blended music with entertainment, marking a shift toward family-oriented projects.[25] Guitarist Tony Valentino managed Tamblyn's short-lived band Chakras in 1969 before stepping back from full-time music; he recorded solo demos in 1982 and maintained occasional involvement in the garage rock scene.[5] Drummer Dick Dodd, who had already begun solo pursuits in 1968 with the single "Guilty" on Square Root Records and the album The First Evolution of Dick Dodd, joined the band Joshua in 1975 for further recording and performances.[5] Dodd continued sporadic musical appearances until his death from cancer in 2013 at age 68.[26] Bassist John Fleck departed the group in 1968 to pursue film work, eventually establishing a career as a cinematographer on notable productions including Jaws 2.[5] Original bassist Gary Lane, who had left the band in 1966, lived a low-profile life outside of music during this period.[15] Although the core group ended regular activity, the Standells persisted in a diminished form with rotating lineups into the early 1970s, including performances at venues like the Beach House in July 1970, but without new recordings or full-band commitments.[5]Cultural persistence during inactivity

During the band's hiatus from 1969 to 1999, "Dirty Water" achieved cult status amid the garage rock revival of the 1970s and 1980s, as collectors and enthusiasts rediscovered the Standells' raw sound through reissues and compilations. Rhino Records' 1983 compilation The Best of the Standells collected key tracks including the hit single, introducing the band's aggressive garage punk to a new generation and sustaining interest in their proto-punk edge.[27] A follow-up archival release, Rarities in 1984, further preserved lesser-known material, highlighting their influence on subsequent rock scenes and contributing to renewed appreciation among fans of 1960s underground music.[28] The song's recognition extended into punk and pub rock circles, exemplified by The Inmates' cover on their 1979 debut album First Offence, which peaked at No. 51 on the Billboard Hot 100 and bridged the Standells' original with late-1970s energy. This adaptation underscored "Dirty Water"'s enduring appeal in punk-adjacent scenes, where its gritty lyrics and snarling delivery resonated with performers drawing from garage rock roots. Media coverage in books and articles on proto-punk and rock history reinforced the Standells' reputation, positioning them as precursors to punk aggression despite their inactivity.[29] In Boston sports culture, "Dirty Water" emerged as an unofficial anthem by the late 1980s, played at Fenway Park after Red Sox victories starting in 1997 but gaining traction earlier through local radio and fan traditions tied to the city's gritty identity.[30] Fan-driven efforts, including bootleg tapes and fanzine features on garage rock obscurities, helped maintain the band's visibility through the 1990s, culminating in heightened interest that paved the way for archival explorations and eventual reunions.[31] These grassroots preservations emphasized the Standells' role in rock's raw underbelly, ensuring "Dirty Water" remained a touchstone for enthusiasts beyond commercial channels.[32]Reformation and later career (2000–present)

1999 reunion and touring revival

In 1999, original members Larry Tamblyn (keyboards and vocals), Tony Valentino (guitar and vocals), and Dick Dodd (drums and vocals) reunited for a performance at the Cavestomp! Festival in New York City, marking the band's first major live appearance in nearly three decades.[5] The show, held on November 7 at the Westbeth Theatre, featured a setlist heavy on their 1960s garage rock classics, including "Riot on Sunset Strip," "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White," and "Dirty Water," and was recorded for posterity. This event revitalized interest in the band, leading to the release of the live album Ban This! Live from Cavestomp! in 2000 on Varèse Sarabande Records, which captured their raw, high-energy style and served as a direct retort to a 1966 radio ban on their music by broadcaster Gordon McLendon.[33] The reunion spurred a touring revival in the early 2000s, with the core trio augmented by bassist Gary Lane, who rejoined for select dates. In 2000, they performed at the Las Vegas Grind festival, emphasizing their proto-punk aggression through blistering renditions of hits that drew enthusiastic crowds nostalgic for the garage rock era.[5] By 2004, the lineup—Tamblyn, Valentino, Dodd, and Lane—took the stage for Game 2 of the World Series at Fenway Park in Boston, performing "Dirty Water" before 50,000 fans and cementing the song's status as a local anthem; they returned to Fenway in 2005 for additional shows on April 11 and September 8.[6] These appearances, along with club gigs across the U.S., showcased the band's enduring ability to deliver visceral, feedback-laden performances despite the passage of time. Lineup stability proved challenging in the mid-2000s as aging affected the original members' touring capacity, though the group maintained a consistent core until 2009, when Valentino, Dodd, and Lane stepped back due to health and scheduling constraints.[6] The revival period highlighted the Standells' focus on live energy over new material, reissuing select tracks via compilations like Rhino Records' earlier Best of the Standells (1983, with ongoing availability) to support their renewed visibility, but no major new studio releases emerged during this era.2010s performances and Larry Tamblyn's death (2025)

Following the 2009 performance at the Cannery Casino and Hotel in Las Vegas, the Standells reformed with a stable lineup centered on founding keyboardist and vocalist Larry Tamblyn and bassist John Fleck, who had originally joined in 1967.[6] Guitarist Mark Adrian and drummer Greg Burnham completed the group, enabling consistent touring through the 2010s.[34] This configuration allowed the band to maintain an active schedule, including a prominent appearance at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Festival in Austin, Texas, in March 2012, where they delivered high-energy sets drawing on their garage rock catalog.[35] The Standells sustained international momentum during the decade, embarking on European tours in 2010 that spanned cities such as Madrid, Paris, London, Berlin, and Athens, where they connected with enthusiastic audiences appreciative of their proto-punk roots.[6] Domestically, they performed at key events like the Monterey Summer of Love Festival in September 2012, briefly reuniting with original drummer Dick Dodd for select shows before his death from cancer on November 29, 2013, at age 68.[36] These outings highlighted Tamblyn's enduring role as the band's creative leader and unofficial historian, preserving their legacy through anecdotes and faithful renditions of classics like "Dirty Water."[37] Bassist John Fleck died on October 18, 2017, from leukemia at age 71.[38] Amid their live commitments, the 2010s saw renewed interest in the Standells' catalog, with several archival releases amplifying their influence. In 2015, a live album titled Live on Tour 1966! was issued, capturing raw performances from their mid-1960s peak and underscoring their snarling stage presence.[39] Digital reissues and expanded editions of core albums like Dirty Water (1966) followed in 2017, making their music more accessible via streaming platforms and introducing it to younger listeners within the garage rock revival scene.[40] Larry Tamblyn, the Standells' co-founder and driving force, died on March 21, 2025, at the age of 82 from a blood disorder.[41] His passing marked a poignant chapter's close for the band, as Tamblyn had not only anchored their sound with his Farfisa organ and vocals but also served as its steadfast guardian, advocating for their place in rock history through interviews and reunions.[2] Tributes poured in from family, including niece Amber Tamblyn, who highlighted his "everlasting cool" and punk-godfather status, while the music community mourned the loss of a garage rock pioneer.[42] As of November 2025, surviving members including Mark Adrian have expressed intentions to honor Tamblyn's legacy through potential tribute performances, though no formal band continuation has been announced.[4]Musical style and influences

Garage rock foundations

The Standells emerged from the vibrant Los Angeles garage rock scene in the early 1960s, where they blended elements of R&B, surf music, and the British Invasion to craft their distinctive sound.[3] Formed in 1962 by keyboardist Larry Tamblyn and guitarist Tony Valentino, the band drew from the raw energy of local clubs and the DIY ethos prevalent in Southern California's burgeoning rock underground, initially performing as a high-energy cover act before honing their original style.[5] Central to their garage rock identity were the unrefined sonic characteristics that defined the genre's gritty appeal: Valentino's raw, distorted guitar riffs provided a jagged edge, complemented by the pounding, relentless drums—especially after Dick Dodd joined in 1964, bringing a propulsive rhythm influenced by his prior R&B experiences—and Tamblyn's swirling organ lines that added a haunting, atmospheric layer to their tracks.[3] This combination evoked the chaotic intensity of teenage garage jams, with simple chord progressions and overdriven amplification capturing the era's amateurish yet fervent spirit.[5] The band's influences were rooted in contemporaries like The Kingsmen, whose 1963 hit "Louie Louie" inspired their own early covers and the sloppily energetic vocal delivery that became a hallmark, as well as local Los Angeles acts such as The Seeds, whose psychedelic-tinged garage sound reinforced the regional emphasis on distorted, feedback-laden performances.[5] These inspirations aligned the Standells with the Nuggets-era garage rock movement of the mid-1960s, a compilation-curated wave of American bands that celebrated a DIY attitude, limited recording resources, and themes of youthful rebellion against societal norms.[2] Over time, the Standells evolved from primarily covering R&B and rock standards—such as tracks by James Brown and The Beatles—to developing originals that amplified their garage foundations, exemplified by "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White" from their 1966 album Why Pick on Me. This shift highlighted their energetic, unpolished production style, recorded with minimal overdubs to preserve the live-wire feel of their club performances, marking a maturation within the garage rock framework while retaining its core rebellion.[3]Proto-punk aggression and innovations

The Standells' sound was characterized by aggressive vocals and instrumentation that prefigured the intensity of 1970s punk rock, with lead singer Dick Dodd's snarling delivery adding a raw, confrontational edge to tracks like "Dirty Water" (1966) and "Riot on Sunset Strip" (1967).[3][43] Dodd's forceful, almost shouted phrasing, combined with the band's driving rhythm section, created a sense of urgency and rebellion that distinguished them from more melodic garage contemporaries.[44] This proto-punk aggression was evident in their live performances, where the group's high-energy style often led to chaotic crowd responses.[3] Lyrically, the Standells explored themes of urban grit, frustration, and anti-authority sentiments, capturing the disillusionment of mid-1960s youth culture. In "Dirty Water," songwriter Ed Cobb depicted Boston's polluted Charles River and prevalent street crime as symbols of societal decay, blending sardonic humor with a gritty portrayal of city life.[44] Similarly, "Riot on Sunset Strip" addressed youth unrest and clashes with authorities during Los Angeles riots, reflecting broader frustrations with establishment control and serving as the theme for a film about teenage rebellion.[45] These themes contributed to the band's reputation for provocative content that resonated with alienated listeners.[46] The band's innovations included feedback-heavy guitars and fast tempos that amplified their raw sound, influencing later proto-punk acts such as the Stooges and MC5. Guitarist Tony Valentino's use of distorted, overdriven tones on a Fender Telecaster through a Vox AC30 amp produced a gritty, abrasive texture, while tracks like "Dirty Water" maintained relentless pacing around 140 beats per minute.[3][47] This approach marked a departure from the era's emerging psychedelic trends, as seen in their 1967 albums Why Pick on Me and Try It, where they preserved a garage rock edge with snarling vocals and fuzz-laden riffs amid occasional experimental flourishes.[3][46] Songs like "Try It" from the latter album exemplified this persistence, featuring punkier elements that were deemed too risqué for airplay due to suggestive lyrics.[48] Critically, the Standells were perceived in the 1960s as a "dangerous" band, with their rowdy shows—marked by smashed equipment and inciting moshes—leading to bans from several venues across the U.S.[3] This notoriety underscored their role as garage rock outliers, earning them inclusion in influential compilations like Lenny Kaye's Nuggets (1972), which highlighted their rough-hewn style as foundational to punk's evolution.[46]Cultural significance

Boston connection and "Dirty Water" as anthem

Although the Standells were formed in Los Angeles and had never visited Boston when "Dirty Water" was recorded in 1965, the song—written by producer Ed Cobb and inspired by news reports of the polluted Charles River—quickly resonated with the city it depicted. Released in 1966, it reached No. 11 on the Billboard Hot 100 and found particular favor in Boston, where audiences sang along enthusiastically during the band's early live performances there, including a riot-torn opening slot for the Rolling Stones that highlighted the track's raw energy. The lyrics' ironic ode to the city's "dirty water," referencing lovers, muggers, and the Fenway Park underpass, captured Boston's tough, unpolished spirit despite its California origins.[49][17] By the mid-1990s, "Dirty Water" had evolved into a staple at Boston Bruins games, and in 1997, the Red Sox officially adopted it as their post-victory anthem at Fenway Park, played after every home win to celebrate triumphs and unite fans. The song's popularity surged during the 1970s, amid the city's busing crises and sporting successes, transforming it from a novelty hit into a symbol of Boston's resilience and pride. Standells keyboardist Larry Tamblyn later reflected on its organic growth, stating, "We had literally no control over it; it just grew naturally," and embraced its status by calling it "Boston's theme song" during visits.[50][49][20] The band's connection deepened through repeated performances at Boston events, earning them honorary status in the city. They played "Dirty Water" at Fenway during the 2004 World Series celebration, accompanying a jet flyover and a cappella national anthem, and the song served as a tribute following the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, with President Obama referencing it in a memorial address as a nod to the city's enduring spirit. Local acts have perpetuated its legacy, notably the Dropkick Murphys, who covered it on their 2002 live album Live on St. Patrick's Day from Boston, MA and frequently perform it to raucous crowds.[49][51][52]Broader impact on rock and punk scenes

The Standells' raw energy and proto-punk attitude significantly influenced 1970s punk bands, with The Ramones explicitly citing them as a key inspiration for their fast-paced, aggressive style. Founding member Larry Tamblyn noted that the Ramones drew from the Standells' sound, which helped shape the New York punk scene's emphasis on short, visceral songs. Similarly, British punk acts like The Damned echoed the Standells' rebellious garage rock ethos, contributing to the genre's transatlantic development as godfathers of punk.[53][54][55] In the 1980s garage revival, Rhino Records' reissues of the Standells' material, such as the 1984 compilation Rarities, played a pivotal role in reintroducing their catalog to new audiences and fueling the neo-garage movement. These efforts directly impacted bands like The Lyres, whose Boston-based sound perpetuated the proto-punk garage tradition pioneered by the Standells, blending organ-driven riffs with high-energy performances. Likewise, The Chesterfield Kings drew from the Standells' aggressive edge, incorporating similar raw instrumentation and attitude into their revivalist sets, helping solidify the decade's underground rock resurgence.[37][5][56] During the 1990s and 2000s, the Standells' proto-punk energy resonated in indie rock, with acts like The White Stripes channeling their stripped-down intensity and garage roots into minimalist, high-impact tracks. This influence extended through broader nods in the alternative scene, where the band's snarling vocals and distorted guitars informed a renewed focus on authenticity over polish. Academic works on garage rock history, such as Garage Rock and Its Roots: Musical Rebels and the Drive for Individuality by Alec Ferrier, recognize the Standells as foundational figures in the genre's evolution toward punk and indie forms.[57][58] Following their 1999 reformation, the Standells experienced a surge in modern relevance, with "Dirty Water" amassing over 12 million streams on Spotify by 2025 and the band maintaining around 70,000 monthly listeners. Their post-reunion touring, including European dates in 2010 and a performance at the SXSW Festival in 2012, integrated them into contemporary festival lineups, bridging classic garage with ongoing punk and alternative scenes.[59][60]Band members

Core and original lineup

The Standells were formed in 1962 in Los Angeles by keyboardist and lead vocalist Larry Tamblyn and guitarist Tony Valentino, initially as a surf and R&B-oriented group performing in clubs.[5] The earliest lineup featured Tamblyn on keyboards and vocals, Valentino on lead guitar, bassist Jody Rich, and drummer Benny King, with the band drawing early influences from British Invasion acts and American R&B.[5] Rich provided the foundational bass lines during the group's initial five-month stint together, while King handled the drumming for their debut performances, including a residency at the Oasis club in Honolulu, Hawaii.[5] This configuration laid the groundwork for the band's raw, energetic style before evolving into its more recognized garage rock sound.[61] By 1963, the lineup shifted with bassist Gary Lane (born Gary McMillan, September 18, 1938, in St. Paul, Minnesota) joining to replace Rich, bringing a steady groove that anchored the band's rhythm section through their mid-1960s recordings.[5][62] Drummer Gary Leeds (born March 9, 1942, in Glendale, California) followed in early 1963, succeeding King and contributing to the group's tightening live performances until his departure in May 1964 to join Johnny Rivers' band.[5] Lane's bass work became integral to the propulsive drive behind hits like "Dirty Water," emphasizing the band's shift toward riff-heavy, aggressive garage rock.[63] The core lineup that defined the Standells' signature 1960s sound solidified in May 1964 with the addition of drummer and vocalist Dick Dodd (born Joseph Richard Dodd Jr., October 27, 1945, in Hermosa Beach, California), a former Mouseketeer whose charismatic stage presence and snarling vocals elevated the band from club act to proto-punk pioneers.[50] Dodd, who served until 1969, handled drums while often taking lead vocal duties, infusing performances with high-energy showmanship and raw aggression that captivated audiences.[36] His contributions were pivotal in the band's live dynamism, complementing the instrumental foundation.[64] Larry Tamblyn (born Lawrence Arnold Tamblyn, February 5, 1943, in Inglewood, California), the brother of actor Russ Tamblyn, remained the band's steadfast leader and creative force, handling keyboards, vocals, and arrangements throughout the 1960s.[4] As co-founder, he composed key melodies and shaped the group's evolution from surf roots to gritty garage rock, writing songs like "Summer Clothes" and overseeing the band's musical direction.[5][65] His organ-driven arrangements added melodic depth to the band's aggressive edge.[2] Tony Valentino (born May 24, 1941, in Longi, Sicily, Italy), an Italian-American immigrant who arrived in the U.S. in 1958, served as the longest-tenured member on lead guitar and occasional vocals from 1962 to 1969.[5][61] His riff-heavy style, played on a Fender Telecaster through a Vox AC30 amp, injected a punk-like intensity into the band's sound, drawing from early rock influences and defining their guitar-driven proto-punk aggression.[47] Valentino's stable presence and technical contributions were essential to the core quartet's cohesion during their peak years.[66]Reformation and supporting members

Following the initial 1999 reunion featuring original members Larry Tamblyn, Tony Valentino, and Dick Dodd, bassist Gary Lane, an original member from the mid-1960s, rejoined the group in 2000 for performances including the Las Vegas Grind event.[5] In 2009, after a performance at the Cannery Casino and Hotel in Las Vegas, the band reformed with Tamblyn on keyboards and vocals, John Fleck on bass—a role he had held from 1966 to 1969 after his time as an original member of the band Love—alongside guitarist Paul Downing and veteran drummer Greg Burnham.[37][6] Fleck provided continuity and creative input during this phase, contributing songs like "All Fall Down" and maintaining the band's raw energy through his established rock experience.[65] The lineup evolved further in the early 2010s, with singer/guitarist Mark Adrian, formerly of the rock group Artica, replacing Paul Downing around 2011; the group performed at the SXSW Festival in March 2012 with this configuration. Adam Marsland briefly joined on guitar and vocals in the mid-2000s alongside Burnham, supporting European tours including stops in Madrid and Bordeaux in 2010.[6] After the deaths of Dodd in 2013 and Lane in 2014, as well as Fleck in 2017, the band adjusted its supporting roster while Tamblyn remained the anchor until his death on March 21, 2025, at age 82 from complications of myelodysplastic syndrome; Burnham continued on drums for high-energy live sets, and Adrian handled co-lead vocals and guitar to adapt the original garage rock style.[4][6] Following Tamblyn's death, the band's future activities remain uncertain, with original member Tony Valentino as the sole surviving core member from the 1960s. This period emphasized stability through veteran players like Fleck during his tenure, ensuring the band's proto-punk aggression persisted in touring revivals.Discography

Studio albums

The band's breakthrough album, Dirty Water, arrived in 1966 on Tower Records, peaking at number 52 on the Billboard 200 chart. Featuring raw garage rock energy, it included the signature hit single "Dirty Water" (which reached number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100) and "Riot on Sunset Strip," both produced by Ed Cobb and capturing the era's youthful rebellion.[67][68] In late 1966, Tower issued Why Pick on Me, a collection of recent singles emphasizing the band's aggressive sound, with standout tracks like the title song and "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White." The album reflected their growing proto-punk edge but saw diminishing chart performance compared to their prior release. The Standells' final 1960s studio effort, Try It, came out in 1967 on Tower Records, incorporating psychedelic elements amid garage rock foundations, highlighted by the controversial title track (banned on some radio stations for its suggestive lyrics) and "All Fall Down." Commercial momentum waned, with no significant chart placement, signaling the end of their active recording phase.[69][70] In 2013, during their reformation, the band released Bump on GRA Records, marking their first original studio album since the 1960s.Live and compilation albums

The Standells' early live album, titled The Standells (also known as In Person at P.J.'s), was released in 1964 by Liberty Records. This album primarily consisted of covers of R&B and rock standards, including tracks like "Big Brother" and "You Can't Do That," and garnered moderate local success in the Los Angeles music scene as the band established itself as a live act. It was later reissued in 1966 as "Live" And Out Of Sight" by Tower Records, which captured performances from their early tours and showcased their raw garage rock energy with tracks like covers of "Gloria" and originals such as "Mr. Nobody."[71][72] This recording, made during a period of intense touring, highlighted the band's aggressive stage presence and instrumental interplay between guitarist Tony Valentino and organist Gary Lane. An early compilation, "The Hot Ones!" (1967, Tower), gathered their singles from the mid-1960s, including hits like "Dirty Water" and "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White," providing a snapshot of their evolution from R&B influences to proto-punk aggression. This release served as a promotional tool amid their rising popularity, emphasizing their Capitol/Tower era output without new material. Following the band's 1969 disbandment, compilations played a crucial role in their revival during the punk and garage rock resurgence of the 1970s and beyond. Their inclusion of "Dirty Water" on the seminal "Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1957-1966" (1972, Elektra), compiled by Lenny Kaye and Jac Holzman, introduced their music to new generations and cemented their status as garage rock pioneers. Rhino Records further amplified this with "The Best of the Standells" (1983), a 12-track overview of their Tower singles and album cuts, and "Rarities" (1984), which unearthed previously unreleased demos and alternate takes from the 1960s.[73][28] In the late 1990s, as the band reformed for occasional performances, live recordings documented their renewed vigor. "Ban This!" (2000, Varèse Sarabande/Cavestomp! Records), featuring 1999 live tracks from New York's Cavestomp! festival, revived their confrontational style with high-energy renditions of classics like "Riot on Sunset Strip," serving as a bridge between their original era and modern audiences. The 1998 Rhino compilation "The Very Best of the Standells" expanded on earlier efforts with 17 tracks spanning their career, including rarities, and helped sustain interest leading into the 21st century. Later releases included the archival live album "Live On Tour - 1966!" (2015, RockBeat Records), a digital and CD edition of previously unreleased 1966 tour recordings that preserved the band's youthful ferocity from shows in Washington state, featuring extended jams on songs like "Good Lovin'" and "Sunny Afternoon."[74] These posthumous and reformation-era projects, alongside festival bootlegs from events like the 2000s Cavestomp series, underscored the enduring appeal of the Standells' live dynamism, contributing significantly to their cult status in garage and punk circles.Singles and EPs

The Standells issued more than a dozen singles between 1963 and 1967, primarily through labels like Liberty, Vee-Jay, and Tower, with several achieving moderate national success on the Billboard Hot 100 during their peak garage rock period.[9] Early releases focused on R&B-inflected rock and roll covers, gaining traction in Los Angeles clubs but limited broader airplay. Their shift to original proto-punk material under Tower Records in 1966 marked their commercial breakthrough, though subsequent singles reflected a brief experimentation with poppier sounds before the band's decline. Key early singles included "The Shake" b/w "Peppermint Beatle" (Liberty, 1964), which became a local hit in Southern California surf and teen scenes, and "Help Yourself" b/w "I'll Go Crazy" (Liberty, 1964), both drawing from British Invasion influences.[75] Another 1964 effort, "The Boy Next Door" (Vee-Jay), showcased their raw energy but failed to chart nationally. In 1965, "Zebra in the Kitchen" b/w "Someday You'll Cry" (MGM) did not chart nationally. The band's signature breakthrough arrived with "Dirty Water" b/w "Rari" (Tower, 1966), a gritty anthem penned by Ed Cobb that peaked at #11 on the Billboard Hot 100 and reportedly sold over one million copies, earning gold certification from the RIAA. Follow-up "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White" b/w "Coming from the Heart" (Tower, 1966) climbed to #43 on the same chart, reinforcing their snarling, rebellious style with organ-driven aggression.[76] Later singles like "Why Pick on Me" b/w "Mr. Nobody" (Tower, 1966) reached #54, while "Try It (The M.F.)" b/w "Poor Shell of a Man" (Tower, 1967) hit #63, signaling a rawer edge amid label pressures. The Standells released a handful of EPs, often as imports or live captures. Notable was the UK-only "Dirty Water" EP (Capitol, 1966), featuring their hit alongside album tracks for European fans. An earlier live EP, "In Person at P.J.'s" (Liberty, 1965), documented club performances and highlighted their high-energy stage presence. In the 2000s, Rhino Records oversaw digital reissues of many singles through compilations like The Best of the Standells (2002), making tracks accessible on platforms like iTunes.| Year | A-Side / B-Side | Label | US Chart Peak (Billboard Hot 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | The Shake / Peppermint Beatle | Liberty | - |

| 1965 | Zebra in the Kitchen / Someday You'll Cry | MGM | - |

| 1966 | Dirty Water / Rari | Tower | 11 |

| 1966 | Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White / Coming from the Heart | Tower | 43 |

| 1966 | Why Pick on Me / Mr. Nobody | Tower | 54 |

| 1967 | Try It (The M.F.) / Poor Shell of a Man | Tower | 63 |