Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Time–frequency analysis

View on WikipediaIn signal processing, time–frequency analysis comprises those techniques that study a signal in both the time and frequency domains simultaneously, using various time–frequency representations. Rather than viewing a 1-dimensional signal (a function, real or complex-valued, whose domain is the real line) and some transform (another function whose domain is the real line, obtained from the original via some transform), time–frequency analysis studies a two-dimensional signal – a function whose domain is the two-dimensional real plane, obtained from the signal via a time–frequency transform.[1][2]

The mathematical motivation for this study is that functions and their transform representation are tightly connected, and they can be understood better by studying them jointly, as a two-dimensional object, rather than separately. A simple example is that the 4-fold periodicity of the Fourier transform – and the fact that two-fold Fourier transform reverses direction – can be interpreted by considering the Fourier transform as a 90° rotation in the associated time–frequency plane: 4 such rotations yield the identity, and 2 such rotations simply reverse direction (reflection through the origin).

The practical motivation for time–frequency analysis is that classical Fourier analysis assumes that signals are infinite in time or periodic, while many signals in practice are of short duration, and change substantially over their duration. For example, traditional musical instruments do not produce infinite duration sinusoids, but instead begin with an attack, then gradually decay. This is poorly represented by traditional methods, which motivates time–frequency analysis.

One of the most basic forms of time–frequency analysis is the short-time Fourier transform (STFT), but more sophisticated techniques have been developed, notably wavelets and least-squares spectral analysis methods for unevenly spaced data.

Motivation

[edit]In signal processing, time–frequency analysis[3] is a body of techniques and methods used for characterizing and manipulating signals whose statistics vary in time, such as transient signals.

It is a generalization and refinement of Fourier analysis, for the case when the signal frequency characteristics are varying with time. Since many signals of interest – such as speech, music, images, and medical signals – have changing frequency characteristics, time–frequency analysis has broad scope of applications.

Whereas the technique of the Fourier transform can be extended to obtain the frequency spectrum of any slowly growing locally integrable signal, this approach requires a complete description of the signal's behavior over all time. Indeed, one can think of points in the (spectral) frequency domain as smearing together information from across the entire time domain. While mathematically elegant, such a technique is not appropriate for analyzing a signal with indeterminate future behavior. For instance, one must presuppose some degree of indeterminate future behavior in any telecommunications systems to achieve non-zero entropy (if one already knows what the other person will say one cannot learn anything).

To harness the power of a frequency representation without the need of a complete characterization in the time domain, one first obtains a time–frequency distribution of the signal, which represents the signal in both the time and frequency domains simultaneously. In such a representation the frequency domain will only reflect the behavior of a temporally localized version of the signal. This enables one to talk sensibly about signals whose component frequencies vary in time.

For instance rather than using tempered distributions to globally transform the following function into the frequency domain one could instead use these methods to describe it as a signal with a time varying frequency.

Once such a representation has been generated other techniques in time–frequency analysis may then be applied to the signal in order to extract information from the signal, to separate the signal from noise or interfering signals, etc.

Time–frequency distribution functions

[edit]Formulations

[edit]There are several different ways to formulate a valid time–frequency distribution function, resulting in several well-known time–frequency distributions, such as:

- Short-time Fourier transform (including the Gabor transform),

- Wavelet transform,

- Bilinear time–frequency distribution function (Wigner distribution function, or WDF),

- Modified Wigner distribution function, Gabor–Wigner distribution function, and so on (see Gabor–Wigner transform).

- Hilbert–Huang transform

More information about the history and the motivation of development of time–frequency distribution can be found in the entry Time–frequency representation.

Ideal TF distribution function

[edit]A time–frequency distribution function ideally has the following properties:[citation needed]

- High resolution in both time and frequency, to make it easier to be analyzed and interpreted.

- No cross-term to avoid confusing real components from artifacts or noise.

- A list of desirable mathematical properties to ensure such methods benefit real-life application.

- Lower computational complexity to ensure the time needed to represent and process a signal on a time–frequency plane allows real-time implementations.

Below is a brief comparison of some selected time–frequency distribution functions.[4]

| Clarity | Cross-term | Good mathematical properties[clarification needed] | Computational complexity | |

| Gabor transform | Worst | No | Worst | Low |

| Wigner distribution function | Best | Yes | Best | High |

| Gabor–Wigner distribution function | Good | Almost eliminated | Good | High |

| Cone-shape distribution function | Good | No (eliminated, in time) | Good | Medium (if recursively defined) |

To analyze the signals well, choosing an appropriate time–frequency distribution function is important. Which time–frequency distribution function should be used depends on the application being considered, as shown by reviewing a list of applications.[5] The high clarity of the Wigner distribution function (WDF) obtained for some signals is due to the auto-correlation function inherent in its formulation; however, the latter also causes the cross-term problem. Therefore, if we want to analyze a single-term signal, using the WDF may be the best approach; if the signal is composed of multiple components, some other methods like the Gabor transform, Gabor-Wigner distribution or Modified B-Distribution functions may be better choices.

As an illustration, magnitudes from non-localized Fourier analysis cannot distinguish the signals:

But time–frequency analysis can.

For a random process x(t), we cannot find the explicit value of x(t).

The value of x(t) is expressed as a probability function.

General random processes

[edit]- Auto-covariance function (ACF)

- In usual, we suppose that for any t,

- (alternative definition of the auto-covariance function)

- Power spectral density (PSD)

- Relation between the WDF (Wigner Distribution Function) and the PSD

- Relation between the ambiguity function and the ACF

Stationary random processes

[edit]- Stationary random process: the statistical properties do not change with t. Its auto-covariance function:

for any , Therefore, PSD, White noise:

, where is some constant.

- When x(t) is stationary,

, (invariant with )

, (nonzero only when )

Additive white noise

[edit]- For additive white noise (AWN),

- Filter Design for a signal in additive white noise

: energy of the signal

: area of the time frequency distribution of the signal

The PSD of the white noise is

Non-stationary random processes

[edit]- If varies with and is nonzero when , then is a non-stationary random process.

- If

- 's have zero mean for all 's

- 's are mutually independent for all 's and 's

- then:

- if , then

Short-time Fourier transform

[edit]- Random process for STFT (Short Time Fourier Transform)

should be satisfied. Otherwise, for zero-mean random process,

- Decompose by the AF and the FRFT. Any non-stationary random process can be expressed as a summation of the fractional Fourier transform (or chirp multiplication) of stationary random process.

Applications

[edit]The following applications need not only the time–frequency distribution functions but also some operations to the signal. The Linear canonical transform (LCT) is really helpful. By LCTs, the shape and location on the time–frequency plane of a signal can be in the arbitrary form that we want it to be. For example, the LCTs can shift the time–frequency distribution to any location, dilate it in the horizontal and vertical direction without changing its area on the plane, shear (or twist) it, and rotate it (Fractional Fourier transform). This powerful operation, LCT, make it more flexible to analyze and apply the time–frequency distributions. The time-frequency analysis have been applied in various applications like, disease detection from biomedical signals and images, vital sign extraction from physiological signals, brain-computer interface from brain signals, machinery fault diagnosis from vibration signals, interference mitigation in spread spectrum communication systems.[7][8]

Instantaneous frequency estimation

[edit]The definition of instantaneous frequency is the time rate of change of phase, or

where is the instantaneous phase of a signal. We can know the instantaneous frequency from the time–frequency plane directly if the image is clear enough. Because the high clarity is critical, we often use WDF to analyze it.

TF filtering and signal decomposition

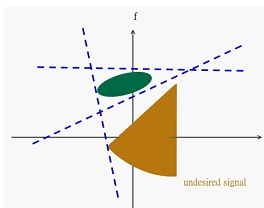

[edit]The goal of filter design is to remove the undesired component of a signal. Conventionally, we can just filter in the time domain or in the frequency domain individually as shown below.

The filtering methods mentioned above can't work well for every signal which may overlap in the time domain or in the frequency domain. By using the time–frequency distribution function, we can filter in the Euclidean time–frequency domain or in the fractional domain by employing the fractional Fourier transform. An example is shown below.

Filter design in time–frequency analysis always deals with signals composed of multiple components, so one cannot use WDF due to cross-term. The Gabor transform, Gabor–Wigner distribution function, or Cohen's class distribution function may be better choices.

The concept of signal decomposition relates to the need to separate one component from the others in a signal; this can be achieved through a filtering operation which require a filter design stage. Such filtering is traditionally done in the time domain or in the frequency domain; however, this may not be possible in the case of non-stationary signals that are multicomponent as such components could overlap in both the time domain and also in the frequency domain; as a consequence, the only possible way to achieve component separation and therefore a signal decomposition is to implement a time–frequency filter.

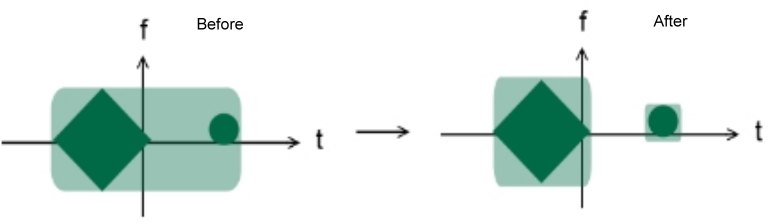

Sampling theory

[edit]By the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, we can conclude that the minimum number of sampling points without aliasing is equivalent to the area of the time–frequency distribution of a signal. (This is actually just an approximation, because the TF area of any signal is infinite.) Below is an example before and after we combine the sampling theory with the time–frequency distribution:

It is noticeable that the number of sampling points decreases after we apply the time–frequency distribution.

When we use the WDF, there might be the cross-term problem (also called interference). On the other hand, using Gabor transform causes an improvement in the clarity and readability of the representation, therefore improving its interpretation and application to practical problems.

Consequently, when the signal we tend to sample is composed of single component, we use the WDF; however, if the signal consists of more than one component, using the Gabor transform, Gabor-Wigner distribution function, or other reduced interference TFDs may achieve better results.

The Balian–Low theorem formalizes this, and provides a bound on the minimum number of time–frequency samples needed.

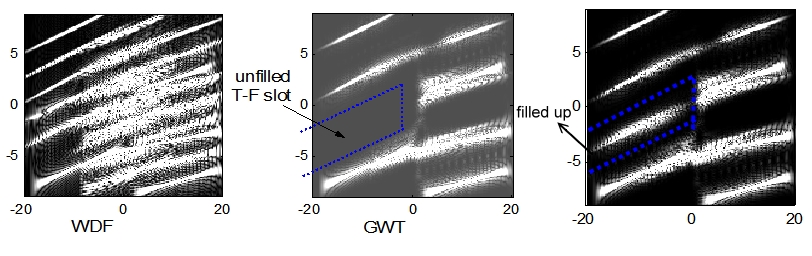

Modulation and multiplexing

[edit]Conventionally, the operation of modulation and multiplexing concentrates in time or in frequency, separately. By taking advantage of the time–frequency distribution, we can make it more efficient to modulate and multiplex. All we have to do is to fill up the time–frequency plane. We present an example as below.

As illustrated in the upper example, using the WDF is not smart since the serious cross-term problem make it difficult to multiplex and modulate.

Electromagnetic wave propagation

[edit]We can represent an electromagnetic wave in the form of a 2 by 1 matrix

which is similar to the time–frequency plane. When electromagnetic wave propagates through free-space, the Fresnel diffraction occurs. We can operate with the 2 by 1 matrix

by LCT with parameter matrix

where z is the propagation distance and is the wavelength. When electromagnetic wave pass through a spherical lens or be reflected by a disk, the parameter matrix should be

and

respectively, where ƒ is the focal length of the lens and R is the radius of the disk. These corresponding results can be obtained from

Optics, acoustics, and biomedicine

[edit]Light is an electromagnetic wave, so time–frequency analysis applies to optics in the same way as for general electromagnetic wave propagation.

Similarly, it is a characteristic of acoustic signals, that their frequency components undergo abrupt variations in time and would hence be not well represented by a single frequency component analysis covering their entire durations.

As acoustic signals are used as speech in communication between the human-sender and -receiver, their undelayedly transmission in technical communication systems is crucial, which makes the use of simpler TFDs, such as the Gabor transform, suitable to analyze these signals in real-time by reducing computational complexity.

If frequency analysis speed is not a limitation, a detailed feature comparison with well defined criteria should be made before selecting a particular TFD. Another approach is to define a signal dependent TFD that is adapted to the data. In biomedicine, one can use time–frequency distribution to analyze the electromyography (EMG), electroencephalography (EEG), electrocardiogram (ECG) or otoacoustic emissions (OAEs).

History

[edit]Early work in time–frequency analysis can be seen in the Haar wavelets (1909) of Alfréd Haar, though these were not significantly applied to signal processing. More substantial work was undertaken by Dennis Gabor, such as Gabor atoms (1947), an early form of wavelets, and the Gabor transform, a modified short-time Fourier transform. The Wigner–Ville distribution (Ville 1948, in a signal processing context) was another foundational step.

Particularly in the 1930s and 1940s, early time–frequency analysis developed in concert with quantum mechanics (Wigner developed the Wigner–Ville distribution in 1932 in quantum mechanics, and Gabor was influenced by quantum mechanics – see Gabor atom); this is reflected in the shared mathematics of the position-momentum plane and the time–frequency plane – as in the Heisenberg uncertainty principle (quantum mechanics) and the Gabor limit (time–frequency analysis), ultimately both reflecting a symplectic structure.

An early practical motivation for time–frequency analysis was the development of radar – see ambiguity function.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ L. Cohen, "Time–Frequency Analysis," Prentice-Hall, New York, 1995. ISBN 978-0135945322

- ^ E. Sejdić, I. Djurović, J. Jiang, "Time-frequency feature representation using energy concentration: An overview of recent advances," Digital Signal Processing, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 153-183, January 2009.

- ^ P. Flandrin, "Time–frequency/Time–Scale Analysis," Wavelet Analysis and its Applications, Vol. 10 Academic Press, San Diego, 1999.

- ^ Shafi, Imran; Ahmad, Jamil; Shah, Syed Ismail; Kashif, F. M. (2009-06-09). "Techniques to Obtain Good Resolution and Concentrated Time-Frequency Distributions: A Review". EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing. 2009 (1) 673539. Bibcode:2009EJASP2009..109S. doi:10.1155/2009/673539. hdl:1721.1/50243. ISSN 1687-6180.

- ^ A. Papandreou-Suppappola, Applications in Time–Frequency Signal Processing (CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla., 2002)

- ^ Ding, Jian-Jiun (2022). Time frequency analysis and wavelet transform class notes. Taipei, Taiwan: Graduate Institute of Communication Engineering, National Taiwan University (NTU).

- ^ Pachori, Ram Bilas. Time-Frequency Analysis Techniques and Their Applications. CRC Press.

- ^ Boashash, Boualem. Time-Frequency Signal Analysis and Processing: A Comprehensive Reference. Elsevier.

![{\displaystyle R_{x}(t,\tau )=E[x(t+\tau /2)x^{*}(t-\tau /2)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dba97ced837f177268653e6108416583a6146411)

![{\displaystyle E[x(t)]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4f7f586f428b9c2f6d38f6ddd862a5379485c8f0)

![{\displaystyle E[x(t+\tau /2)x^{*}(t-\tau /2)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d1e4e44402416a9c66beb12946d6d9a98031808d)

![{\displaystyle {\overset {\land }{R_{x}}}(t,\tau )=E[x(t)x(t+\tau )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/88e31df0436c04b90d7270838345630147ed4b28)

![{\displaystyle E[W_{x}(t,f)]=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }E[x(t+\tau /2)x^{*}(t-\tau /2)]\cdot e^{-j2\pi f\tau }\cdot d\tau }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/403669072db5e6b603d38f2342d458fe9c2ffd62)

![{\displaystyle E[A_{X}(\eta ,\tau )]=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }E[x(t+\tau /2)x^{*}(t-\tau /2)]e^{-j2\pi t\eta }dt}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2f7855543c99b2734b0976e4afaa436e2cdf91ed)

![{\displaystyle R_{x}(\tau )=E[x(\tau /2)x^{*}(-\tau /2)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/32bbb23856db67fa4496549bed6e8bedbae228ef)

![{\displaystyle E[W_{x}(t,f)]=S_{x}(f)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9e93a2bf9ba460d2f30da477d016356ff59e21ec)

![{\displaystyle E[A_{x}(\eta ,\tau )]=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }R_{x}(\tau )\cdot e^{-j2\pi t\eta }\cdot dt}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5b64bd68fb318ca6cc5e6f6e639c9d64aeeb7be7)

![{\displaystyle E[W_{g}(t,f)]=\sigma }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f7efa3126af03af9f7f7f60d17b4e16602f3994)

![{\displaystyle E[A_{x}(\eta ,\tau )]=\sigma \delta (\tau )\delta (\eta )}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5882e628b0b6e4eef34d4985f583a3c8bef44800)

![{\displaystyle E[W_{x}(t,f)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2e82af0d314bb32b72a40af9acf5b08af5c4baa)

![{\displaystyle E[A_{x}(\eta ,\tau )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9fa5f52be40791b38a55fec2fa9e888ddb8d9833)

![{\displaystyle E[x_{m}(t+\tau /2)x_{n}^{*}(t-\tau /2)]=E[x_{m}(t+\tau /2)]E[x_{n}^{*}(t-\tau /2)]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed2c03fff86d1d9769a67f16544ebf7f881617b7)

![{\displaystyle E[W_{h}(t,f)]=\sum _{n=1}^{k}E[W_{x_{n}}(t,f)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7f48363e2b835b2be2f0519e7d9b66ca7a862810)

![{\displaystyle E[A_{h}(\eta ,\tau )]=\sum _{n=1}^{k}E[A_{x_{n}}(\eta ,\tau )]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e10bcea52301c98919f93f9342640c4a1537eb05)

![{\displaystyle E[x(t)]\neq 0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3a78a42a18ea8067b8166d625b72f1135a267279)

![{\displaystyle E[X(t,f)]=E[\int _{t-B}^{t+B}x(\tau )w(t-\tau )e^{-j2\pi f\tau }d\tau ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3830241043666becce3d587b7023a4b9430ceed9)

![{\displaystyle =\int _{t-B}^{t+B}E[x(\tau )]w(t-\tau )e^{-j2\pi f\tau }d\tau }](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5bc111c58a3fe7c36b60a43d6efa23f1685c66d)

![{\displaystyle E[X(t,f)]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1639afad7896fa3fc66c95039c5b6f3b58a1260d)