Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cadaver

View on Wikipedia

A cadaver, often known as a corpse, is a dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Students in medical school study and dissect cadavers as a part of their education. Others who study cadavers include archaeologists and arts students.[1] In addition, a cadaver may be used in the development and evaluation of surgical instruments.[2]

The term cadaver is used in courts of law (and, to a lesser extent, also by media outlets such as newspapers) to refer to a dead body, as well as by recovery teams searching for bodies in natural disasters. The word comes from the Latin word cadere ("to fall"). Related terms include cadaverous (resembling a cadaver) and cadaveric spasm (a muscle spasm causing a dead body to twitch or jerk). A cadaver graft (also called “postmortem graft”) is the grafting of tissue from a dead body onto a living human to repair a defect or disfigurement. Cadavers can be observed for their stages of decomposition, helping to determine how long a body has been dead.[3]

Cadavers have been used in art to depict the human body in paintings and drawings more accurately.[4]

Human decay

[edit]

Observation of the various stages of decomposition can help determine how long a body has been dead.

Stages of decomposition

[edit]- The first stage is autolysis, more commonly known as self-digestion, during which the body's cells are destroyed through the action of their own digestive enzymes. However, these enzymes are released into the cells because of cessation of the active processes in the cells, not as an active process. In other words, though autolysis resembles the active process of digestion of nutrients by live cells, the dead cells are not actively digesting themselves as is often claimed in popular literature and as the synonym of autolysis – self-digestion – seems to imply. As a result of autolysis, liquid is created that seeps between the layers of skin and results in peeling of the skin. During this stage, flies (when present) begin to lay eggs in the openings of the body: eyes, nostrils, mouth, ears, open wounds, and other orifices. Hatched larvae (maggots) of blowflies subsequently get under the skin and begin to consume the body.

- The second stage of decomposition is bloating. Bacteria in the gut begin to break down the tissues of the body, releasing gas that accumulates in the intestines, which becomes trapped because of the early collapse of the small intestine. This bloating occurs largely in the abdomen, and sometimes in the mouth, tongue, and genitals. This usually happens around the second week of decomposition. Gas accumulation and bloating will continue until the body is decomposed sufficiently for the gas to escape.

- The third stage is putrefaction. It is the final and longest stage. Putrefaction is where the larger structures of the body break down, and tissues liquefy. The digestive organs, brain, and lungs are the first to disintegrate. Under normal conditions, the organs are unidentifiable after three weeks. The muscles may be eaten by bacteria or devoured by animals. Eventually, sometimes after several years, all that remains is the skeleton. In acid-rich soils, the skeleton will eventually dissolve into its base chemicals.

The rate of decomposition depends on many factors including temperature and the environment. The warmer and more humid the environment, the faster the body is broken down.[5] The presence of carrion-consuming animals will also result in exposure of the skeleton as they consume parts of the decomposing body.

History

[edit]The history of the use of cadavers is filled with controversy, scientific advancements, and new discoveries. Beginning in the 3rd century ancient Greece two physicians by the name of Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos[6] practiced the dissection of cadavers in Alexandria, and it was the dominant means of learning anatomy.[7] After both of these men died, the popularity of anatomical dissection decreased until it was not used at all. It was not revived until the 12th century and it became increasingly popular in the 17th century and has been used ever since.[6]

Even though both Herophilus and Erasistratus had permission to use cadavers for dissection, there was still a large amount of taboo surrounding the use of cadavers for anatomical purposes, and these feelings continued for hundreds of years. From the time that anatomical dissection gained its roots in the 3rd century to around the 18th century, it was associated with dishonor, immorality, and unethical behavior. Many of these notions were because of religious beliefs and esthetic taboos,[7] and were deeply entrenched in the beliefs of the public and the church. As mentioned above, the dissection of cadavers began to once again take hold around the 12th century. At this time dissection was still seen as dishonorable; however, it was not outright banned. Instead, the church put forth certain edicts for banning and allowing certain practices. One that was monumental for scientific advancement was issued by the Holy Roman emperor Frederick II in 1231.[7] This decree stated that a human body would be dissected once every five years for anatomical studies, and that attendance was required for all who were training to or currently practicing medicine or surgery.[7] This led to the first sanctioned human dissection since 300 B.C., which was performed publicly by Mondino de Liuzzi.[7] This time period created a great deal of enthusiasm in what human dissection could do for science and attracted students from all over Europe to begin studying medicine.

In light of the new discoveries and advancements that were being made, religious moderation of dissection relaxed significantly; however, the public perception of it was still negative. Because of this perception, the only legal source of cadavers was the corpses of criminals who were executed, usually by hanging.[6] Many of the offenders whose crimes “warranted” dissection and their families even considered dissection to be more terrifying and demeaning than the crime or death penalty itself.[6] There were many fights and sometimes even riots when relatives and friends of the deceased and soon to be dissected tried to stop the delivery of corpses from the place of hanging to the anatomists.[8] The government at the time (17th century) took advantage of these qualms by using dissection as a threat against committing serious crimes. They even increased the number of crimes that were punished by hanging to over 200 offenses.[8] Nevertheless, as dissection of cadavers became even more popular, anatomists were forced to find other ways to obtain cadavers.

As demand increased for cadavers from universities across the world, people began grave-robbing. These corpses were transported and put on sale for local anatomy professors to take back to their students.[6] The public tended to look the other way when it came to grave-robbing because the affected was usually poor or a part of a marginalized society.[6] There was more out-cry if the affluent or prominent members of society were affected, and this led to a riot in New York most commonly referred to as the Resurrection Riot of 1788. It all started when a doctor waved the arm of a cadaver at a young boy looking through the window, who then went home and told his father. Worrying that his recently deceased wife's grave had been robbed, he went to check on it and realized that it had been.[6] This story spread and people accused local physicians and anatomists. The riot grew to 5,000 people and by the end medical students and doctors were beaten and six people were killed.[6] This led to many legal adjustments such as the Anatomy Acts put forth by the U.S. government. These acts opened up other avenues to obtaining corpses for scientific purposes with Massachusetts being the first to do so. In 1830 and 1833, they allowed unclaimed bodies to be used for dissection.[6] Laws in almost every state were subsequently passed and grave-robbing was essentially eradicated.

Although dissection became increasingly accepted throughout the years, it was still very much disapproved by the American public in the beginning of the 20th century. The disapproval mostly came from religious objections and dissection being associated with unclaimed bodies and therefore a mark of poverty.[6] There were many people that attempted to display dissection in a positive light, for example 200 prominent New York physicians publicly said they would donate their bodies after their death.[6] This and other efforts only helped in minor ways, and public opinion was much more affected by the exposure of the corrupt funeral industry.[6] It was found that the cost of dying was incredibly high and a large amount of funeral homes were scamming people into paying more than they had to.[6] These exposures did not necessarily remove stigma but created fear that a person and their families would be victimized by scheming funeral directors, therefore making people reconsider body donation.[6]

In art

[edit]Since early history, the instances of inclusion and representation of corpses in art have been numerous; for instance, as in Neo-Assyrian sculpted reliefs of floating corpses on a river (c. 640 BCE), and in Aristophanes's comedy The Frogs (405 BCE), to memento mori and cadaver monuments.

The study and teaching of anatomy through the ages would not have been possible without sketches and detailed drawings of discoveries when working with human corpses. The artistic depiction of the placement of body parts plays a crucial role in studying anatomy and in assisting those working with the human body. These images serve as the only glance into the body that most will never witness in person.[9]

Da Vinci collaborated with Andreas Vesalius who also worked with many young artists to illustrate Vesalius’ book "De Humani Corporis Fabrica" and this launched the use of labelling anatomical features to better describe them. It is believed that Vesalius used cadavers of executed criminals in his work due to the inability to secure bodies for this type of work and dissection. He also went to great measures to utilize a spirit of art appreciation in his drawings and also employed other artists to assist in these illustrations.[9]

The study of the human body was not isolated to only medical doctors and students, as many artists reflected their expertise through masterful drawings and paintings. The detailed study of human and animal anatomy, as well as the dissection of corpses, was utilized by early Italian renaissance man Leonardo da Vinci in an effort to more accurately depict the human figure through his work. He studied the anatomy from an exterior perspective as an apprentice under Andrea del Verrocchio that started in 1466.[10] During his apprenticeship, Leonardo mastered drawing detailed versions of anatomical structures such as muscles and tendons by 1472.[10]

His approach to the depiction of the human body was much like that of the study of architecture, providing multiple views and three-dimensional perspectives of what he witnessed in person. One of the first examples of this is using the three dimensional perspectives to draw a skull in 1489.[11] Further study under Verrocchio, some of Leonardo da Vinci's anatomical work was published in his book A Treatise on Painting.[12][self-published source?] A few years later, in 1516, he partnered with professor and anatomist Marcantonio della Torre in Florence, Italy to take his study further. The two began to conduct dissections on human corpses at the Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova and later at hospitals in Milan and Rome. Through his study, da Vinci was perhaps the first to accurately draw the natural position of the human fetus in the womb, via cadaver of a late mother and her unborn child.[13] It is speculated that he conducted approximately 30 dissections total.[14] His work with cadavers allowed him to portray the first drawings of the umbilical cord, uterus, cervix and vagina and ultimately dispute beliefs that the uterus had multiple chambers in the case of multiple births.[13] It is reported that between 1504 and 1507, he experimented with the brain of an ox by injecting a tube into the ventricular cavities, injecting hot wax, and scraping off the brain leaving a cast of the ventricles. Da Vinci's efforts proved to be very helpful in the study of the brain's ventricular system.[15] Da Vinci gained an understanding of what was happening mechanically under the skin to better portray the body through art.[14] For example, he removed the facial skin of the cadaver to more closely observe and draw the detailed muscles that move the lips to obtain a holistic understanding of that system.[16] He also conducted a thorough study of the foot and ankle that continues to be consistent with current clinical theories and practice.[14] His work with the shoulder also mirrors modern understanding of its movement and functions, utilizing a mechanical description likening it to ropes and pulleys.[14] He also was one of the first to study neuroanatomy and made great advances regarding the understanding of the anatomy of the eye, optic nerves and the spine, but unfortunately his later discovered notes were disorganized and difficult to decipher due to his practice of reverse script writing (mirror writing).[17]

For centuries artists have used their knowledge gleaned from the study of anatomy and the use of cadavers to better present a more accurate and lively representation of the human body in their artwork and mostly in paintings. It is thought that Michelangelo and/or Raphael may have also conducted dissections.[9]

Importance in science

[edit]Cadavers are used in many different facets throughout the scientific community. One important aspect of cadavers' use for science is that they have provided science with a vast amount of information dealing with the anatomy of the human body. Cadavers allowed scientists to investigate the human body on a deeper level which resulted in identification of certain body parts and organs. Two Greek scientists, Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos were the first to use cadavers in the third century B.C.[18] Through the dissection of cadavers, Herophilus made multiple discoveries concerning the anatomy of the human body, including the difference between the four ventricles within the brain, identification of seven pairs of cranial nerves, the difference between sensory and motor nerves, and the discovery of the cornea, retina and choroid coat within the eye. Herophilus also discovered the valves within a human heart while Erasistratus identified their function by testing the irreversibility of the blood flow through the valves. Erasistratus also discovered and distinguished between many details within the veins and arteries of the human body. Herophilus later provides descriptions of the human liver, the pancreas, and the male and female reproductive systems due to the dissection of the human body. Cadavers allowed Herophilus to determine that the womb in which fetus’ grow and develop in is not bicameral. This goes against the original notion of the womb in which was thought to have two chambers; however, Herophilus discovered the womb to only have one chamber. Herophilus also discovered the ovaries, the broad ligaments and the tubes within the female reproductive system.[18] During this time period, cadavers were one of the only ways to develop an understanding of the anatomy of the human body.

Galen (130–201 AD) connected the famous works of Aristotle and other Greek physicians to his understanding of the human body.[19] Galenic anatomy and physiology were considered to be the most prominent methods to teach when dealing with the study of the human body during this time period.[20] Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), known as the father of modern human anatomy, based his knowledge off of Galen's findings and his own dissection of human cadavers.[20][21] Vesalius performed multiple dissections on cadavers for medical students to recognize and understand how the interior body parts of a human being worked. Cadavers also helped Vesalius discredit previous notions of work published by the Greek physician Galen dealing with certain functions of the brain and human body.[22] Vesalius concluded that Galen never did use cadavers in order to gain a proper understanding of human anatomy but instead used previous knowledge from his predecessors.[20]

Importance in medical field

[edit]In the present day, cadavers are used within medicine and surgery to further knowledge on human gross anatomy.[23] Surgeons have dissected and examined cadavers before surgical procedures on living patients to identify any possible deviations within the surgical area of interest.[24] New types of surgical procedures can lead to numerous obstacles involved within the procedure which can be eliminated through prior knowledge from the dissection of a cadaver.[25]

Cadavers not only provide medical students and doctors knowledge about the different functions of the human body, but they also provide multiple causes of malfunction within the human body. Galen (250 AD), a Greek physician, was one of the first to associate events that occurred during a human's life with the internal ramifications found later after death. A simple autopsy of a cadaver can help determine origins of deadly diseases or disorders. Autopsies also can provide information on how certain drugs or procedures have been effective within the cadaver and how humans respond to certain injuries.[26]

Appendectomies, the removal of the appendix, are performed 28,000 times a year in the United States and are still practiced on human cadavers and not with technology simulations.[27] Gross anatomy, a common course in medical school studying the visual structures of the body, gives students the opportunity to have a hands-on learning environment. The need for cadavers has also grown outside of academic programs for research. Organizations like Science Care and the Anatomy Gifts Registry help send bodies where they are needed most.[27]

Preserving for use in dissection

[edit]For a cadaver to be viable and ideal for anatomical study and dissection, the body must be refrigerated or the preservation process must begin within 24 hours of death.[28] This preservation may be accomplished by embalming using a mixture of embalming fluids, or with a relatively new method called plastination. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages in regards to preparing bodies for anatomical dissection in the educational setting.

Embalming with fluids

[edit]

The practice of embalming via chemical fluids has been used for centuries. The main objectives of this form of preservation are to keep the body from decomposing, help the tissues retain their color and softness, prevent both biological and environmental hazards, and preserve the anatomical structures in their natural forms.[31] This is accomplished with a variety of chemical substances that can be separated generally into groups by their purposes. Disinfectants are used to kill any potential microbes. Preservatives are used to halt the action of decomposing organisms, deprive these organisms of nutrition, and alter chemical structures in the body to prevent decomposition. Various modifying agents are used to maintain the moisture, pH, and osmotic properties of the tissues along with anticoagulants to keep blood from clotting within the cardiovascular system. Other chemicals may also be used to keep the tissue from carrying displeasing odors or particularly unnatural colors.[31]

Embalming practice has changed a great deal in the last few hundred years. Modern embalming for anatomical purposes no longer includes evisceration, as this disrupts the organs in ways that would be disadvantageous for the study of anatomy.[31] As with the mixtures of chemicals, embalmers practicing today can use different methods for introducing fluids into the cadaver. Fluid can be injected into the arterial system (typically through the carotid or femoral arteries), the main body cavities, under the skin, or the cadaver can be introduced to fluids at the outer surface of the skin via immersion.[32]

Different embalming services use different types and ratios of fluids, but typical embalming chemicals include formaldehyde, phenol, methanol, and glycerin.[33] These fluids are combined in varying ratios depending on the source, but are generally also mixed with large amounts of water.

Chemicals and their roles in embalming

[edit]

Formaldehyde is very widely used in the process of embalming. It is a fixative, and kills bacteria, fungus, and insects. It prevents decay by keeping decomposing microorganisms from surviving on and in the cadaver. It also cures the tissues it is used in so that they cannot serve as nutrients for these organisms. While formaldehyde is a good antiseptic, it has certain disadvantages as well. When used in embalming, it causes blood to clot and tissues to harden, it turns the skin gray, and its fumes are both malodorous and toxic if inhaled. However, its abilities to prevent decay and tan tissue without ruining its structural integrity have led to its continued widespread use to this day.[31]

Phenol is a disinfectant that functions as an antibacterial and antifungal agent. It prevents the growth of mold in its liquefied form. Its disinfectant qualities rely on its ability to denature proteins and dismantle cell walls, but this unfortunately has the added side effect of drying tissues and occasionally results in a degree of discoloration.[31]

Methanol is an additive with disinfectant properties. It helps regulate the osmotic balance of the embalming fluid, and it is a decent anti-refrigerant. It has been noted to be acutely toxic to humans.[31]

Glycerin is a wetting agent that preserves liquid in the tissues of the cadaver. While it is not itself a true disinfectant, mixing it with formaldehyde greatly increases the effectiveness of formaldehyde's disinfectant properties.[31]

Advantages and disadvantages of using traditionally embalmed cadavers

[edit]The use of traditionally embalmed cadavers is and has been the standard for medical education. Many medical and dental institutions still show a preference for these today, even with the advent of more advanced technology like digital models or synthetic cadavers.[34] Cadavers embalmed with fluid do present a greater health risk to anatomists than these other methods as some of the chemicals used in the embalming process are toxic, and imperfectly embalmed cadavers may carry a risk of infection.[33]

Plastination

[edit]Gunther von Hagens invented plastination at Heidelberg University in Heidelberg, Germany in 1977.[35] This method of cadaver preservation involves the replacement of fluid and soluble lipids in a body with plastics.[35] The resulting preserved bodies are called plastinates.

Whole-body plastination begins with much the same method as traditional embalming; a mixture of embalming fluids and water are pumped through the cadaver via arterial injection. After this step is complete, the anatomist may choose to dissect parts of the body to expose particular anatomical structures for study. After any desired dissection is completed, the cadaver is submerged in acetone. The acetone draws the moisture and soluble fats from the body and flows in to replace them. The cadaver is then placed in a bath of the plastic or resin of the practitioner's choice and the step known as forced impregnation begins. The bath generates a vacuum that causes acetone to vaporize, drawing the plastic or resin into the cells as it leaves. Once this is done the cadaver is positioned, the plastic inside it is cured, and the specimen is ready for use.[36]

Advantages and disadvantages of using plastinates

[edit]Plastinates are advantageous in the study of anatomy as they provide durable, non-toxic specimens that are easy to store. However, they still have not truly gained ground against the traditionally embalmed cadaver. Plastinated cadavers are not accessible for some institutions, some educators believe the experience gained during embalmed cadaver dissection is more valuable, and some simply do not have the resources to acquire or use plastinates.[34]

Body snatching

[edit]

While many cadavers were murderers provided by the state, few of these corpses were available for everyone to dissect. The first recorded body snatching was performed by four medical students who were arrested in 1319[citation needed] for grave-robbing. In the 1700s most body snatchers were doctors, anatomy professors or their students. By 1828, some anatomists were paying others to perform the exhumation. People in this profession were commonly known in the medical community as "resurrection men".[37]

The London Borough Gang was a group of resurrection men that worked from 1802 to 1825. These men provided a number of schools with cadavers, and members of the schools would use influence to keep these men out of jail. Members of rival gangs would often report members of other gangs, or desecrate a graveyard in order to cause a public upset, making it so that rival gangs would not be able to operate.[37]

Selling murder victims

[edit]From 1827 to 1828 in Scotland, a number of people were murdered, and the bodies were sold to medical schools for research purposes, known as the West Port murders. The Anatomy Act 1832 was created to ensure that relatives of the deceased submitted to the use of their kin in dissection and other scientific processes.[clarification needed] Public response to the West Port murders was a factor in the passage of this bill, as well as the acts committed by the London Burkers.

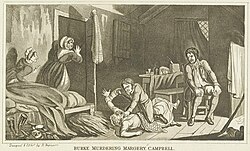

Stories appeared of people murdering and selling the cadaver. Two of the well-known cases are that of Burke and Hare, and that of Bishop, May, and Williams.

- Burke and Hare – Burke and Hare ran a boarding house. When one of their tenants died, they brought him to Robert Knox's anatomy classroom in Edinburgh, where they were paid seven pounds for the body. Realizing the possible profit, they murdered 16 people by asphyxiation over the next year and sold their bodies to Knox. They were eventually caught when a tenant returned to her bed only to encounter a corpse. Hare testified against Burke in exchange for amnesty and Burke was found guilty, hanged, and publicly dissected.[38]

- London Burkers, Bishop, May and Williams – These body snatchers killed three boys, ages 10, 11 and 14 years old. The anatomist that they sold the cadavers to was suspicious. To delay their departure, the anatomist stated that he needed to break a 50-pound note and sent for the police who then arrested the men. In his confession Bishop claimed to have body-snatched 500 to 1000 bodies in his career.[39]

Motor vehicle safety

[edit]Prior to the development of crash test dummies, cadavers were used to make motor vehicles safer.[40] Cadavers have helped set guidelines on the safety features of vehicles ranging from laminated windshields to seat belt airbags. The first recorded use of cadaver crash test dummies was performed by Lawrence Patrick, in the 1930s, after using his own body, and of his students, to test the limits of the human body. His first cadaver use was when he tossed a cadaver down an elevator shaft. He learned that the human skull can withstand up to one and a half tons for one second before experiencing any type of damage.[41]

In a 1995 study, it was approximated that improvements made to cars since cadaver testing have prevented 143,000 injuries and 4250 deaths. Miniature accelerometers are placed on the bone of the tested area of the cadaver. Damage is then inflicted on the cadaver with different tools including; linear impactors, pendulums, or falling weights. The cadaver may also be placed on an impact sled, simulating a crash. After these tests are completed, the cadaver is examined with an x-ray, looking for any damage, and returned to the Anatomy Department.[42] Cadaver use contributed to Ford's inflatable rear seat belts introduced in the 2011 Explorer.[43]

Public view of cadaver crash test dummies

[edit]After a New York Times article published in 1993, the public became aware of the use of cadavers in crash testing. The article focused on Heidelberg University's use of approximately 200 adult and children cadavers.[44] After public outcry, the university was ordered to prove that the families of the cadavers approved their use in testing.[45]

See also

[edit]- Anatomy Act 1832

- Andreas Vesalius

- Autopsy

- Body farm

- Cadaverine, a foul-smelling chemical released during decomposition

- Conservation and restoration of human remains

- Dissection

- Eloise Cemetery

- Kadaververwertungsanstalt

- Morgue

- Necroviolence, abuse of corpses

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of Cadaver". RxList. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ van den Haak, Lukas; Alleblas, Chantal; Rhemrev, Johann P.; Scheltes, Jules; Nieboer, Theodoor Elbert; Jansen, Frank Willem. National Institutes for Health - National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information: December 4, 2017 "Human cadavers to evaluate prototypes of minimally invasive surgical instruments: A feasibility study". Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ "Cadaver". Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ^ New Oxford Dictionary of English, 1999. cadaver Medicine: or poetic/literary: a cait.

- ^ "Decomposition – The Forensics Library". aboutforensics.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2020-10-10. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Hulkower, Raphael (2011). From sacrilege to privilege: "the tale of body procurement for anatomical dissection in the United States". Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

- ^ a b c d e Ghosh SK (September 2015). "Human cadaveric dissection: a historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 48 (3): 153–69. doi:10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.153. PMC 4582158. PMID 26417475.

- ^ a b Mitchell PD, Boston C, Chamberlain AT, Chaplin S, Chauhan V, Evans J, et al. (August 2011). "The study of anatomy in England from 1700 to the early 20th century". Journal of Anatomy. 219 (2): 91–99. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2011.01381.x. PMC 3162231. PMID 21496014.

- ^ a b c Mavrodi A, Paraskevas G (December 2013). "Evolution of the paranasal sinuses' anatomy through the ages". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 46 (4): 235–38. doi:10.5115/acb.2013.46.4.235. PMC 3875840. PMID 24386595.

- ^ a b "Leonardo Da Vinci – The Complete Works – Biography". leonardodavinci.net. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- ^ "Anatomy in the Renaissance". metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- ^ Da Vinci L (1967). The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1105310164.

- ^ a b Wilkins DG (2001). "Review of The Writings and Drawings of : Order and Chaos in Early Modern Thought". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 32 (2): 509–11. doi:10.2307/2671780. JSTOR 2671780.

- ^ a b c d Jastifer JR, Toledo-Pereyra LH (October 2012). "Leonardo da Vinci's foot: historical evidence of concept". Journal of Investigative Surgery. 25 (5): 281–85. doi:10.3109/08941939.2012.725011. PMID 23020268. S2CID 19186635.

- ^ Paluzzi A, Belli A, Bain P, Viva L (December 2007). "Brain 'imaging' in the Renaissance". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 100 (12): 540–43. doi:10.1177/014107680710001209. PMC 2121627. PMID 18065703.

- ^ Pater W (2011), "Leonardo da Vinci", The Works of Walter Pater, Cambridge University Press, pp. 98–129, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139062213.007, ISBN 978-1139062213

- ^ Nanda A, Khan IS, Apuzzo ML (March 2016). "Renaissance Neurosurgery: Italy's Iconic Contributions". World Neurosurgery. 87: 647–55. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.11.016. PMID 26585723.

- ^ a b von Staden H (1992). "The discovery of the body: human dissection and its cultural contexts in ancient Greece". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 65 (3): 223–41. PMC 2589595. PMID 1285450.

- ^ "Comparative Anatomy: Andreas Vesalius". evolution.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ a b c Zampieri F, ElMaghawry M, Zanatta A, Thiene G (2015-12-22). "Andreas Vesalius: Celebrating 500 years of dissecting nature". Global Cardiology Science & Practice. 2015 (5): 66. doi:10.5339/gcsp.2015.66. PMC 4762440. PMID 28127546.

- ^ Leslie, Mitch (2003-08-08). "Lesson From the Anatomy Master". Science. 301 (5634): 741. doi:10.1126/science.301.5634.741a. S2CID 220091493.

- ^ Simpkins CA, Simpkins AM (2013). "The Birth of a New Science". Neuroscience for Clinicians. New York: Springer. pp. 3–24. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4842-6_1. ISBN 978-1-4614-4841-9.

- ^ Cornwall J, Stringer MD (October 2009). "The wider importance of cadavers: educational and research diversity from a body bequest program". Anatomical Sciences Education. 2 (5): 234–47. doi:10.1002/ase.103. PMID 19728368. S2CID 21914260.

- ^ Prakash KG, Saniya K (January 2014). "A study on radial artery in cadavers and its clinical importance" (PDF). International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 3 (2): 254–62. doi:10.5958/j.2319-5886.3.2.056.

- ^ Eizenberg N (2015-12-30). "Anatomy and its impact on medicine: Will it continue?". The Australasian Medical Journal. 8 (12): 373–77. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2015.2550. PMC 4701898. PMID 26759611.

- ^ Cantor N (2010). After We Die: The Life and Times of the Human Cadaver. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- ^ a b McCall M (July 29, 2016). "The Secret Lives of Cadavers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016.

- ^ McCall M (2016-07-29). "The Secret Lives of Cadavers". National Geographic. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ Besouchet 1993, p. 603.

- ^ Rezzutti 2019, pp. 498–499.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brenner E (March 2014). "Human body preservation – old and new techniques". Journal of Anatomy. 224 (3): 316–44. doi:10.1111/joa.12160. PMC 3931544. PMID 24438435.

- ^ Batra AP, Khurana BS, Mahajan A, Kaur N (2010). "Embalming and Other Methods of Dead Body Preservation". International Journal of Medical Toxicology & Legal Medicine. 12 (3): 15–19.

- ^ a b "Training for Anatomy Students". Environmental Health & Safety. Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2018-11-25. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ a b Klaus RM, Royer DF, Stabio ME (March 2018). "Use and perceptions of plastination among medical anatomy educators in the United States". Clinical Anatomy. 31 (2): 282–92. doi:10.1002/ca.23025. PMID 29178370. S2CID 46860561.

- ^ a b Pashaei S (December 2010). "A Brief Review on the History, Methods and Applications of Plastination". International Journal of Morphology. 28 (4): 1075–79. doi:10.4067/s0717-95022010000400014.

- ^ "Plastination Technique". Körperwelten. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ a b Waite FC (July 1945). "Grave Robbing in New England". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association. 33 (3): 272–94. PMC 194496. PMID 16016694.

- ^ Rosner L (2011). The Anatomy Murders. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812203554.

Being the True and Spectacular History of Edinburgh's Notorious Burke and Hare and of the Man of Science Who Abetted Them in the Commission of Their Most Heinous Crimes

- ^ Kelly T (1832). The history of the London Burkers. London: Wellcome Library.

Containing a faithful and authentic account of the horrid acts of the noted Resurrectionists, Bishop, Williams, May, etc., etc., and their trial and condemnation at the Old Bailey for the wilful murder of Carlo Ferrari, with the criminals' confessions after trial. Including also the life, character, and behaviour of the atrocious Eliza Ross. The murderer of Mrs. Walsh, etc., etc

- ^ Fox M (18 February 2005). "Samuel Alderson, Crash-Test Dummy Inventor, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- ^ "The Driving Dead: Human Cadavers Still Used In Car Crash Testing". Autoblog. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- ^ King AI, Viano DC, Mizeres N, States JD (April 1995). "Humanitarian benefits of cadaver research on injury prevention". The Journal of Trauma. 38 (4): 564–69. doi:10.1097/00005373-199504000-00016. PMID 7723096.

- ^ "How Cadavers Made Your Car Safer". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- ^ "German University Said to Use Corpses in Auto Crash Tests". The New York Times. The Associated Press. 24 November 1993. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- ^ "German university must prove families ok'd tests on cadaver". DeseretNews.com. 1993-11-24. Archived from the original on October 5, 2014. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Jones DG (2000). Speaking for the Dead: Cadavers in Biology and Medicine. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-2073-0.

- Roach M (2003). Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers. New York: W. W. Norton and Company Inc.

- Shultz S (1992). Body Snatching: the Robbing of Graves for the Education of Physicians. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company Inc.

- Wright-St Clair RE (February 1961). "Murder For Anatomy". New Zealand Medical Journal. 60: 64–69.

- Besouchet, Lídia (1993). Pedro II e o Século XIX (in Portuguese) (2nd ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. ISBN 978-85-209-0494-7.

- Rezzutti, Paulo (2019). D. Pedro II: a história não contada: O último imperador do Novo Mundo revelado por cartas e documentos inéditos (in Portuguese). Leya; 2019. ISBN 978-85-7734-677-6.