Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wollo Province

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Wollo (Amharic: ወሎ) was a historical province of northern Ethiopia. During the Middle Ages this province name was Bete Amhara and it was the centre of the Solomonic emperors. Bete Amhara had an illustrious place in Ethiopian political and cultural history. It was the center of the Solomonic Dynasty established by Emperor Yekuno Amlak around Lake Hayq in 1270. Bete Amhara was bounded on the west by the Abbay, on the south by the river Wanchet, on the north by the Bashilo River and on the east by the Escarpment that separate it from the Afar Desert.[1]

The original Wollo province was mainly only the area of modern-day South Wollo. But in the 1940s, under Emperor Haile Selassie, administration changes were made and provinces such as Lasta, Angot (now known as Raya), and parts of Afar lands were incorporated into Wollo.

History

[edit]

Today's Wollo was long the center of Ethiopia (half under Agew/Zagwe and half under the Solomonic leadership). The people of Amhara and Zagwe Provinces (today's Wollo) were the strongest adherents of Christianity and both believed in Israelite Semitic Biblical Ancestry Zagwe claimed lineage from Moses while the Solomonids claimed lineage from Solomon, and the beliefs and customs of the Church from an essential part of tradition and culture to this area.[2] Evidence of Wollo's political importance to Ethiopia in the medieval era was that the region's rulers played a disproportionate role in the politics of the Ethiopian state. In the medieval era, the Tsahife Lam (ጻሕፈ ላም), governor of the Bete Amhara province, was the most senior military officer next to the Emperor. Along with that, the Jantirar of Ambassel (the center of Bete Amhara and lordship of Yekuno Amlak himself prior to his ascension as Emperor of Ethiopia), was tasked with protecting Amba Geshen. Believers contend that the monastic life is the highest stage of Christian life. Devout Christians hope to live their last years as monks or nuns, and many take monastic vows during old age. The Monastic school of Lake Hayq founded in 1248 by Aba Iyesus-Mo'a was the fundamental school to Saints, scholars and Christians. The Monasteries spread along with the Ethiopian Empire and Tekle-Haymanot (1215–1313) was trained at Hayq by Iyasus Mo'a and started the important Monastic community of Debre Asbo in Shewa Amhara Debre Libanos, Abune Hirute Amlak was also trained in this Monastery by Iyasus Mo'a and started the imperative Monastic community of Daga Estifanos in Lake Tsana and Aba Georgis Zegasecha trained and started the Monastic community of Gasecha.[3]

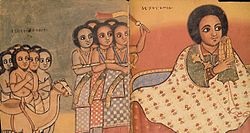

As a result of this, several Church works were performed and it was the land of Saints and Christian kings. Therefore, many famous Churches were built by Christian kings and Monasteries were established by great Saints and wonderful Rock Hewn Churches were carved out of rock. Furthermore, it was the center of Church Education. For example, from the Monastery of Hayq Estifanos the well-known Saints and Christian kings had learnt Church education. For this reason, literature, paintings and other heritages flourished throughout the land. In the region many Rock Hewn Churches were built by Saints like, King Abrha and Astbha. Most of them were in the place of Woleka Debresina but they destructed and hidden during the invasion of Ahmad Gragn. Aba Betselote Micheal, Aba Giorgis Zegasecha, Aba Tsegie Dengel, Abune Yaekob Zedebrekerbe and by King Lalibela, the rock Church builder - 1140-79 A.D. had a set of ten Rock Hewn Churches built in his capital of Roha, which was later renamed Lalibela. It is also said that he built the Gezaza Abune Gebre Menfes Kidus Church (Gezaza Abbo) in this region around Wegde. All these are rock hewn Churches carved in solid rock, deserve to be taken as few among wonders and are a remarkable monument to the skill and craftsmanship of the Ethiopians.

Mekane Silasse Church was established before 485 years in 1513 E.C. The foundation was started by Atse Naod (1489–1500) and it was finished by his son Atse Lebna Dengel (1500–1513). This Church is different from other Churches because it took 25 years to construct it. Atse Naod worked on it for 13 years but he died before finishing it. So, his son Lebna Dengel finished it after 12 years by constructing a great Church and more beautiful than his father. At the inauguration of the Church in 1513 many famous persons were present. Among them, the Portuguese priest and historian writer, Francisco Alvarez was the one who recorded the ceremonies of the Church inauguration at that time. He admired and writes about the Church's architectural design.

The Church was constructed from Geha stone and it had a Mekdes, Kidist and Kine Mahilet. The four sides of the Mekdes and Kidist were equal in size and shape but the shape of the Kine Mahlet was circular. The Church was also much wider and bigger than other Churches of the time found around Wesel.[4] The Portuguese priest and historian writer, Francisco Alvaraze said the following about its architectural design: “the wall of this Church was made from systematically carved stones and it was designed by a graphic decoration …..the door of the main entrance was covered by gold and silver. Inside the gold and silver there were some precious stones. The roof was laid down on the six columns of the Church and the outer part of the roof was supported by 61 long columns. There were also sixteen curtains made of golden cotton cloth.[citation needed]

On the other hand, the historical writer of Ahmad Gragn, Arab Faqeh, recorded about its architectural design before the destruction of the Church. He admired its construction and architectural design and said that the following: “there was one church in Bete Amhara which no church could imitate in Habesha land".[5] It was constructed by the father of Lebene Dengel, King Naod. Its work and ornament had taken 13 years but king Naod died before finishing it. His son Lebna Dengel finished it after 25 years. He finished the Church by covering all part of it with gold above what his father had done. So the Church reflects like a fire, because, it was covered by gold and all the church holy treasures liturgical objects) were made from gold and silver. The width of the Church was more than a hundred yards and the height was also more than fifty yards ... Christians called the Church Mekane Silasse..... In this Church, the tomb of Emperor Na'od who is the grand son of Zera Yacob and the son of Be’ede Mariam is found.”[citation needed]

Although the presence of Muslim communities in Wollo is dated to at least the 8th century[6] the province was chiefly inhabit by Christians Amhara.[7] The Jihad of Ahmad Gran and the Oromo expansion latter on brought a significant cultural change in /Wollo. A province which was once a centre of Christianity and Christian culture have become the centre of Islam and Islamic studies.[8]

The Oromo clans that invaded Wollo in the late 16th century adopted Islam during their expansion process. And when they arrived in the province they committed various atrocities against its local Christian Amhara population; they burnt churches in every district which they invade, killed the clergy and sold Christians into slavery. Emperor Tekle Giyorgis I decided to punish the Oromo over the atrocities that they committed against the Christian population of Bete Amhara but failed to completely operate it due to internal problems that he faced.[9] The Amhara were pushed into the western districts of Sayint, Delanta and Wadla. Whereas part of them remain isolated and clustered in highland areas of wollo; especially in Warra Himano and Ambassel. Christianity virtually disappeared in much of what was the medieval province of Amhara.[10][11]

After occupying and settling in the province, the Oromos changed the original names of many districts in Bete Amhara and named them after their clans and sub-clans, such as: Borona, Qallu, Bati, Wuchale, Worra Himano, Lagga Ghora, Tehuladere, Laggambo, and Lagga-Hidda.[12][13][14] According to J. Spencer Trimingham it become regular among foreign travellers to call all the Muslim population of the region “Wollo Galla” but many of the Wollo do not belong to the Oromo ethnic group at all. That is especially the case with the population in the highland regions of Wollo; such as the massifs of Legambo and Legahida and the Were Ilu Plateau. These from ethnical point of view are Abyssinians whom their only common link with Oromo is the Islam religion.[15]

With the adoption of the 1995 constitution & the establishment of ethnic federalism system in Ethiopia, parts of the expanded Wollo province, which were mostly inhabited by Afar people were given to the new Afar Region. The new Amhara Region absorbed the remainder of the province in the Ethiopian Highlands and kept the name Wollo for its two new zones (South Wollo Zone & North Wollo Zone). Wollo is known to be the origin of the four melodic-modes (kignits) of Ethiopia.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 46–47.

- ^ Abbink, Jon (2016-07-07). "In memoriam Donald Nathan Levine (1931–2015)". Aethiopica. 18: 213–222. doi:10.15460/aethiopica.18.1.936. ISSN 2194-4024.

- ^ Blackhurst, Hector (October 1974). "Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270–1527. By Taddesse Tamrat. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972. Pp. xv + 327, bibl., ill., maps. £5·50". Africa. 44 (4): 427–428. doi:10.2307/1159069. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1159069. S2CID 146979138.

- ^ Beckingham, C.F.; Huntingford, G.W.B., eds. (2017-05-15). The Prester John of the Indies. doi:10.4324/9781315554013. ISBN 9781315554013.

- ^ "Futūḥ al-Ḥabasha". Christian-Muslim Relations 1500 - 1900. doi:10.1163/2451-9537_cmrii_com_26077. Retrieved 2020-12-15.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 64–65.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham (1952). Islam in Ethiopia. Oxford University Press. p. 193.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 77–78.

- ^ Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1975-09-18). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 572–573. ISBN 978-0-521-20413-2.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 75.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 95.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 76–77.

- ^ Levine, Donald N. (1974). Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-226-22967-6.

- ^ Melaku, Misganaw Tadesse (2020). "Social and political history of Wollo Province in Ethiopia: 1769-1916". University of the Western Cape: 82–83.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham (1952). Islam in Ethiopia. Oxford University Press. p. 196.

Wollo Province

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Administrative Divisions

![Map of Wollo Province in Ethiopia (1943-1987)][float-right] Wollo Province historically occupied a central position in northern Ethiopia, extending across terrains that now primarily fall within the Amhara Region, with portions overlapping into contemporary Afar and Tigray regions.[1] Its boundaries bordered Tigre to the north, the Awash River valley areas to the east, Shoa and Gojjam to the south and west, encompassing diverse highland and lowland landscapes.[1] In the late imperial period, the province spanned approximately 75,780 square kilometers, ranking as Ethiopia's third-largest administrative unit after Hararghe and Sidamo.[1] Following the 1991 overthrow of the Derg regime and the adoption of ethnic federalism, Wollo was dissolved and reorganized into North Wollo and South Wollo Zones within the Amhara National Regional State, reflecting a shift to ethnically delineated boundaries.[9] This restructuring, formalized in the 1994 constitution, aimed to align administrative units with predominant ethnic groups but has contributed to inter-regional disputes, including claims over border areas in North Wollo such as Welkait with the Tigray Region, as ethnic federalism redefined territorial concepts and intensified local conflicts.[10] [9] North Wollo Zone borders South Wollo to the south, South Gondar Zone to the west, Tigray Region to the north, and Afar Region to the east, with Weldiya serving as its administrative center.[11] South Wollo Zone adjoins North Shewa and Oromia Special Zone to the south, East Gojjam to the west, South Gondar to the northwest, North Wollo to the north, Afar to the northeast, and Oromia Region to the east, featuring major urban centers including Dessie and Kombolcha.[12] These zones together represent the core of former Wollo territory in the modern federal structure, though historical extents included additional adjacent areas now administered separately.[3]Topography, Climate, and Natural Resources

Wollo Province features a diverse topography characterized by highland plateaus, steep escarpments descending into the Rift Valley, and semi-arid lowlands toward the east. Elevations vary significantly, ranging from approximately 1,500 meters in the eastern lowlands to over 4,200 meters in the central and northern highlands, as observed in areas like the Abune Yosef mountain range. This relief includes dissected plateaus and volcanic highlands in the west, transitioning to arid depressions influenced by proximity to the Afar region.[13] The climate of Wollo is predominantly semi-arid to sub-humid, with bimodal rainfall patterns typical of the Ethiopian highlands, though distributions are erratic and highly variable. Annual precipitation in North Wollo reaches a maximum of about 1,058 mm, concentrated in the main rainy season (June-September) and a shorter secondary season (February-May), but inter-annual variability exacerbates drought risks. Average temperatures decrease with elevation, from warmer lowlands around 25°C to cooler highlands below 15°C, contributing to frost in higher altitudes. The region has historically experienced severe droughts, such as those in the 1970s and 1980s, linked to prolonged rainfall deficits and poor distribution.[14][15] Natural resources include fertile volcanic soils in the highlands suitable for crops like teff and barley, though these are fragile and prone to erosion. Water resources feature rivers such as the Borkena, a tributary of the Awash River originating in South Wollo's uplands and flowing eastward for about 300 km. Mineral deposits are limited compared to neighboring regions, with no major exploitable reserves prominently documented in Wollo itself. Environmental challenges, including deforestation from fuelwood collection and overgrazing, have accelerated soil erosion, reducing land productivity and increasing vulnerability to climate variability.[16][17][18]History

Origins and Early Settlement

Archaeological surveys in South Wollo, such as those conducted in the Dessie Zurya Woreda from 2018 to 2021, reveal evidence of early human settlements linked to pre-Aksumite cultural phases, with artifacts indicating occupation by agro-pastoral communities in the highlands by the first millennium BCE. These findings include traces of metallurgical activities and basic agrarian infrastructure, suggesting initial exploitation of the region's volcanic soils for farming and herding. The causal logic of settlement patterns favors such elevated terrains due to their moderate climate, which supports crop cultivation like teff and barley precursors, and defenses against lowland raids, drawing migrants from surrounding arid zones.[19] Rock art and lithic tools scattered across Wollo's escarpments, dated tentatively to around 1000 BCE through comparative analysis with northern Ethiopian sites, point to hunter-gatherer transitions toward sedentism, potentially influenced by broader Horn of Africa dynamics. These motifs depict pastoral scenes and rudimentary symbolism, aligning with pre-Aksumite traditions observed in adjacent regions, though direct attribution remains provisional due to limited excavation. Empirical data from regional surveys underscore a substrate of indigenous Cushitic-speaking groups, including proto-Agaw populations, who likely formed the core early settlers, adapting to the terrain's biodiversity for mixed economies.[20] By the early first millennium CE, the emergence of Agaw communities—evidenced by linguistic remnants and oral traditions corroborated by ethnographic studies—marked a consolidation of highland societies, predating significant Semitic overlays. These groups, as original north-central Ethiopian inhabitants, leveraged Wollo's plateaus for terrace farming innovations, fostering demographic growth amid ecological stability. Early Amhara precursors, arising from Semitic linguistic shifts around this era via Arabian Peninsula migrations and local admixture, began integrating into the cultural fabric, though archaeological primacy rests with Agaw agrarian foundations rather than migratory elites.[21][19]Medieval Period and Christian-Amhara Core

In the medieval period, the region encompassing modern Wollo Province was known as Bete Amhara, serving as a central hub for Amharic-speaking Christian communities and the political heartland of Ethiopian highland governance.[1] This area fostered a robust continuity of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity, with local populations maintaining deep-rooted adherence to the faith amid the Zagwe Dynasty's rule from approximately 1137 to 1270 CE.[22] The dynasty, originating from the Agaw people of Lasta in northern Wollo, established its capital at Roha (later renamed Lalibela), emphasizing religious devotion through monumental architecture and centralized administration that integrated Christian traditions.[23] The Zagwe rulers, despite their non-Semitic Agaw ethnic background, upheld and expanded Orthodox Christian practices, countering any notion of the region as peripheral by demonstrating sophisticated statecraft and cultural patronage.[22] King Lalibela, reigning around 1200 CE, commissioned the excavation of eleven monolithic rock-hewn churches at the site, symbolizing a "New Jerusalem" and exemplifying engineering feats that involved carving entire structures from single basalt outcrops, complete with trenches, tunnels, and drainage systems.[24] These churches, including Bete Maryam, not only served liturgical purposes but also reinforced communal identity tied to biblical narratives, with Amhara inhabitants tracing their ancestry to ancient Israelites through the legendary Queen of Sheba and King Solomon lineage preserved in Orthodox lore.[25] Bete Amhara's Christian-Amhara core manifested in governance structures that prioritized ecclesiastical alliances, monastic education, and defense against external threats, laying foundations for subsequent Solomonic restoration under Yekuno Amlak, an Amhara prince from the province who defeated the last Zagwe king in 1270 CE.[26] This era's achievements in rock architecture and religious scholarship underscored Wollo's integral role in sustaining Ethiopia's highland Christian civilization, with enduring monasteries and liturgical centers evidencing a resilient cultural continuum.[25]Islamic Expansion and Ottoman Influences

Islam arrived in Wollo Province through gradual processes linked to trans-Saharan and Red Sea trade routes beginning as early as the 8th century CE, with Muslim merchants and migrants establishing small communities in lowland areas such as Wore-Himano district.[27] These early settlements facilitated peaceful conversions among local Argobba and other Semitic-speaking groups via economic incentives and intermarriage, though the Muslim population remained a minority compared to the Christian highlands until the 16th century.[28] The pace of Islamization accelerated dramatically during the Adal Sultanate's invasions from 1529 to 1543, led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad Gragn), who targeted Christian centers in the Ethiopian highlands, including Wollo's strategic passes and settlements.[29] Gragn's forces, bolstered by Ottoman-supplied firearms, matchlocks, and artillery—estimated at up to 2,000 musketeers and 900 specialist troops—enabled conquests that overran much of Wollo by the mid-1530s, destroying churches, monasteries, and royal chronicles while imposing Islamic governance.[30] This military superiority, including the first widespread use of gunpowder weapons against Ethiopian armies, caused significant demographic shifts as Muslim Somali, Harla, and Afar fighters settled in eastern and lowland Wollo, displacing or assimilating Christian populations.[3] While mosque construction and veneration of Sufi saints, such as at sites like Tiru Sina, later served as mechanisms for cultural integration and voluntary adherence in Wollo's mixed communities, Gragn's campaigns involved coercive elements, including the execution of resistant clergy and forced relocations that pressured conversions amid widespread devastation.[31] Local resistance persisted, with highland militias and Christian nobles mounting guerrilla opposition, contributing to Gragn's eventual defeat at the Battle of Wayna Daga in 1543 by a coalition of Ethiopian and Portuguese forces, which halted further entrenchment but left enduring Muslim majorities in Wollo's lowlands. These events underscore conquest and demographic engineering as primary causal drivers over purely pacific diffusion, with Ottoman logistical aid tipping the balance toward rapid territorial gains.[32]Imperial Consolidation and 19th-20th Century Governance

During the mid-19th century, Emperor Tewodros II (r. 1855–1868) initiated efforts to centralize imperial authority over Wollo, a region experiencing renewed Islamic influence and semi-autonomous Muslim principalities, as part of broader campaigns to unify fragmented Ethiopian territories.[1] His successor, Yohannes IV (r. 1872–1889), continued these reconquests, launching military expeditions against Wollo's Muslim leaders to reassert Christian imperial dominance and curb the expansion of Islam, which had gained ground through local dynasties and trade networks.[1] These actions reflected a strategic imperative to secure the empire's northern frontiers amid external threats from Egyptian and Sudanese forces, though full consolidation remained elusive until later rulers. The late 19th century saw decisive integration under Emperor Menelik II (r. 1889–1913), who empowered Ras Mikael (1850–1918), originally named Mohammed Ali, as the key governor of Wollo after Mikael's annexation of rival territories around 1881.[33] A convert to Orthodox Christianity, Ras Mikael founded Dessie as Wollo's administrative capital and led its cavalry in the pivotal Battle of Adwa in 1896, contributing significantly to the imperial victory against Italian invaders.[34] His loyalty exemplified how the Solomonic dynasty maintained control in religiously diverse areas by co-opting capable local elites, fostering stability through a blend of coercion and patronage rather than uniform religious enforcement. In the 20th century under Emperor Haile Selassie (r. 1930–1974), Wollo functioned as a formal province with Dessie as its seat, governed through appointed ras and nazirates within the enduring feudal land tenure system of gult grants to nobles, which concentrated control among imperial loyalists while exacerbating peasant obligations and inequities.[35] Infrastructure development lagged behind central highlands, with limited road networks hindering integration despite national initiatives like railway extensions; this peripheral status preserved local customs but perpetuated economic disparities tied to subsistence agriculture.[36] The centralized monarchy's approach—appointing overseers attuned to Wollo's Muslim-Christian mosaic—sustained governance amid diversity, prioritizing imperial cohesion over radical reforms that might provoke unrest.Post-Imperial Era and Dissolution

The Derg regime, which seized power in September 1974, initiated sweeping land reforms across Ethiopia, including Wollo Province. On March 20, 1975, Proclamation No. 31 nationalized all rural land, declaring it the property of the state and distributing usufruct rights to peasant associations while abolishing tenancy, large holdings over 10 hectares, and feudal landlordism.[37] These measures aimed to dismantle the imperial feudal system but disrupted traditional farming practices and local power structures in Wollo's agrarian economy.[38] Subsequent Derg policies shifted toward collectivization, establishing producer cooperatives and state farms to boost output, yet these efforts largely failed due to peasant resistance, poor implementation, and coercive villagization programs that relocated rural populations into consolidated settlements.[39] In Wollo, such interventions compounded vulnerabilities from earlier droughts, like the 1973 crisis, by undermining incentives for individual production and exacerbating food shortages into the 1980s through administrative inefficiencies and forced relocations.[40] Empirical assessments indicate these socialist experiments yielded declining per capita agricultural output, with collectivized areas underperforming private holdings by up to 30% in yield.[41] The EPRDF's victory in May 1991 ended the Derg and introduced ethnic federalism via the 1995 Constitution, restructuring Ethiopia into nine (later twelve) ethnic-based regions to devolve power along linguistic lines. Wollo Province was dissolved, its territories fragmented into the Amhara Region's North Wollo, South Wollo, and Wag Hemra zones, severing historical administrative unity.[42] This system, modeled on Soviet precedents and led by Tigrayan-dominated EPRDF, prioritized ethnic self-determination but causally incentivized irredentism by tying governance to fluid ethnic claims, evidenced by post-1991 surges in boundary disputes—such as Amhara assertions over Welkait and Raya areas historically linked to Wollo—and over 200 documented ethnic conflicts by 2016.[43][44] In the 2020s, rising Amhara nationalism has fueled demands to restore Wollo's distinct administrative identity within or beyond the Amhara Region, framing federal fragmentation as eroding cultural cohesion and historical entitlements. Advocacy groups and regional movements, including Fano militias, assert control over Wollo-linked territories to counter perceived marginalization under ethnic federalism, reflecting broader empirical patterns of provincial revivalism amid federalism's destabilizing effects on multi-ethnic unity.[45][46] These pushes underscore federalism's causal role in amplifying sub-regional identities over integrated provincial legacies, with data showing heightened intra-Amhara zonal tensions paralleling inter-regional clashes.[47]Demographics and Ethnicity

Population Statistics and Distribution

In the 1980s, prior to administrative restructuring, Wollo Province had an estimated population of 2-3 million, heavily impacted by recurrent droughts and famines that led to significant mortality and displacement.[48] The 1973-74 and 1984-85 famines particularly devastated northern areas, reducing local populations through death and out-migration while highlighting vulnerabilities in highland subsistence communities.[49] The 2007 Ethiopian Population and Housing Census, conducted by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA), recorded 1,500,303 residents in North Wollo Zone and 2,518,862 in South Wollo Zone, totaling approximately 4.02 million across the core successor areas of former Wollo Province.[50] These figures reflected an average annual growth rate of about 2.6% nationally, driven by high fertility and declining mortality, with rural densities exceeding 100 persons per square kilometer in fertile highland kebeles.[51] By the 2016-2017 census period, preliminary data and projections indicated expansion to roughly 5-6 million, though exact zone-level enumerations faced delays due to logistical challenges; South Wollo alone approached 3.5 million by recent estimates.[52] Projections for 2025, based on sustained 2.5-3% annual growth amid improving healthcare access, suggest a total exceeding 6.5 million, concentrated in agrarian highland districts.[53] Population distribution remains predominantly rural, with over 85% residing in dispersed highland villages supported by enset and cereal cultivation, fostering dense settlements in elevations above 2,000 meters.[54] Urbanization is limited but centers on Dessie, the principal hub with an estimated 270,000 inhabitants as of recent projections, serving as a commercial and administrative node for surrounding woredas.[55] Migration patterns, documented in UN and IOM assessments, show outflows from drought-prone lowlands and conflict zones, with seasonal labor movements to urban areas or eastern regions exacerbating rural depopulation; conflicts since 2020 have displaced hundreds of thousands internally, while recurrent dry spells prompt livestock and human mobility southward.[56][14]Ethnic Composition and Linguistic Patterns

Wollo Province was ethnically dominated by the Amhara people, who formed over 95% of the population, with small minorities of Argobba, Afar, and Oromo groups concentrated in peripheral areas.[4] [57] The Argobba, a Semitic-speaking minority, historically resided in northern pockets, while Afar communities occupied eastern lowlands bordering their namesake region, and Oromo settlements appeared sporadically near southern and western boundaries.[58] This demographic structure underscored Amhara predominance, reinforced by cultural and administrative integration under imperial and post-imperial governance. Linguistically, Amharic served as the dominant lingua franca across Wollo, fostering cohesion amid ethnic minorities and acting as a counterweight to fragmenting forces like Ethiopia's ethnic federalism.[59] The local Wollo variety of Amharic exhibited distinct phonological traits, such as variations in vowel harmony and consonant clusters influenced by regional substrates, yet remained mutually intelligible with central dialects like those of Shewa.[60] Historical assimilation of Agaw populations into the Amhara fold, beginning around 1270, accelerated the shift to Amharic as the primary language, with Agaw linguistic elements largely supplanted through intermarriage and Christianization processes.[61] This linguistic unification helped mitigate divisions, contrasting with federal policies that amplified minority assertions and sparked territorial disputes over Wollo's borders, particularly from adjacent Oromo claims.[42]Religion

Pre-Islamic Religious Landscape

The pre-Islamic religious landscape of Wollo Province centered on the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, established through the Aksumite Kingdom's adoption of Christianity under King Ezana around 330 AD.[62] Aksumite expansion into the central highlands, including Wollo, promoted Christian settlement via church foundations and military outposts, fostering a network of Orthodox communities by the 5th-6th centuries.[63] This era marked Wollo as a Christian stronghold, with the church exerting influence over land tenure and social order prior to the 16th century.[64] Monasteries emerged as key institutions, embodying clerical authority in governance; abbots and priests advised rulers on policy and mediated disputes, while serving as repositories for Ge'ez manuscripts and theological scholarship.[65] Sites like Hayk Estifanos Monastery, founded circa 850-900 AD on Lake Hayq in northern Wollo, highlight this monastic tradition, with structures dating to the 9th-10th centuries evidencing sustained investment in religious infrastructure.[66] Archaeological surveys in South Wollo, such as the ruined Church of Qirqos at Kǝmǝrdǝngay, reveal basilical layouts and cross motifs consistent with early Aksumite-derived Christian architecture from the 6th-9th centuries.[67] Syncretic elements persisted, integrating pre-Christian indigenous animism and Judaic influences—such as Sabbath observances and ark veneration—with Orthodox liturgy, reflecting gradual conversion processes in highland Agaw and Semitic populations before widespread Islamization.[28] Empirical continuity is evident in preserved sites like the 12th-century rock-hewn churches of Lalibela, which embody Solomonic-era Orthodox symbolism and demonstrate Wollo's role as a pilgrimage hub rooted in pre-Islamic foundations.[68] These features underscore the region's foundational Orthodox identity, sustained through clerical land grants and ritual practices amid localized pagan residues.

.svg/250px-Wello_in_Ethiopia_(1943-1987).svg.png)

.svg/1980px-Wello_in_Ethiopia_(1943-1987).svg.png)