Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Duoprism

View on Wikipedia| Set of uniform p-q duoprisms | |

| Type | Prismatic uniform 4-polytopes |

| Schläfli symbol | {p}×{q} |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Cells | p q-gonal prisms, q p-gonal prisms |

| Faces | pq squares, p q-gons, q p-gons |

| Edges | 2pq |

| Vertices | pq |

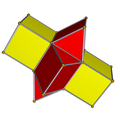

| Vertex figure |  disphenoid |

| Symmetry | [p,2,q], order 4pq |

| Dual | p-q duopyramid |

| Properties | convex, vertex-uniform |

| Set of uniform p-p duoprisms | |

| Type | Prismatic uniform 4-polytope |

| Schläfli symbol | {p}×{p} |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Cells | 2p p-gonal prisms |

| Faces | p2 squares, 2p p-gons |

| Edges | 2p2 |

| Vertices | p2 |

| Symmetry | [p,2,p] = [2p,2+,2p], order 8p2 |

| Dual | p-p duopyramid |

| Properties | convex, vertex-uniform, Facet-transitive |

In geometry of 4 dimensions or higher, a double prism[1] or duoprism is a polytope resulting from the Cartesian product of two polytopes, each of two dimensions or higher. The Cartesian product of an n-polytope and an m-polytope is an (n+m)-polytope, where n and m are dimensions of 2 (polygon) or higher.

The lowest-dimensional duoprisms exist in 4-dimensional space as 4-polytopes being the Cartesian product of two polygons in 2-dimensional Euclidean space. More precisely, it is the set of points:

where P1 and P2 are the sets of the points contained in the respective polygons. Such a duoprism is convex if both bases are convex, and is bounded by prismatic cells.

Nomenclature

[edit]Four-dimensional duoprisms are considered to be prismatic 4-polytopes. A duoprism constructed from two regular polygons of the same edge length is a uniform duoprism.

A duoprism made of n-polygons and m-polygons is named by prefixing 'duoprism' with the names of the base polygons, for example: a triangular-pentagonal duoprism is the Cartesian product of a triangle and a pentagon.

An alternative, more concise way of specifying a particular duoprism is by prefixing with numbers denoting the base polygons, for example: 3,5-duoprism for the triangular-pentagonal duoprism.

Other alternative names:

- q-gonal-p-gonal prism

- q-gonal-p-gonal double prism

- q-gonal-p-gonal hyperprism

The term duoprism is coined by George Olshevsky, shortened from double prism. John Horton Conway proposed a similar name proprism for product prism, a Cartesian product of two or more polytopes of dimension at least two. The duoprisms are proprisms formed from exactly two polytopes.

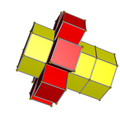

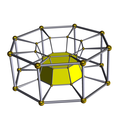

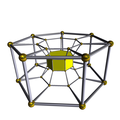

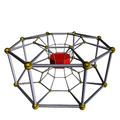

Example 16-16 duoprism

[edit]Schlegel diagram Projection from the center of one 16-gonal prism, and all but one of the opposite 16-gonal prisms are shown. |

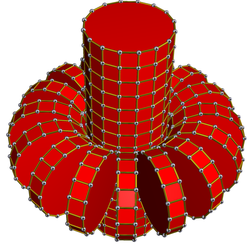

net The two sets of 16-gonal prisms are shown. The top and bottom faces of the vertical cylinder are connected when folded together in 4D. |

Geometry of 4-dimensional duoprisms

[edit]A 4-dimensional uniform duoprism is created by the product of a regular n-sided polygon and a regular m-sided polygon with the same edge length. It is bounded by n m-gonal prisms and m n-gonal prisms. For example, the Cartesian product of a triangle and a hexagon is a duoprism bounded by 6 triangular prisms and 3 hexagonal prisms.

- When m and n are identical, the resulting duoprism is bounded by 2n identical n-gonal prisms. For example, the Cartesian product of two triangles is a duoprism bounded by 6 triangular prisms.

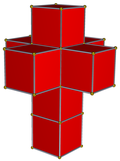

- When m and n are identically 4, the resulting duoprism is bounded by 8 square prisms (cubes), and is identical to the tesseract.

The m-gonal prisms are attached to each other via their m-gonal faces, and form a closed loop. Similarly, the n-gonal prisms are attached to each other via their n-gonal faces, and form a second loop perpendicular to the first. These two loops are attached to each other via their square faces, and are mutually perpendicular.

As m and n approach infinity, the corresponding duoprisms approach the duocylinder. As such, duoprisms are useful as non-quadric approximations of the duocylinder.

Nets

[edit] 3-3 | |||||||

3-4 |

4-4 | ||||||

3-5 |

4-5 |

5-5 | |||||

3-6 |

4-6 |

5-6 |

6-6 | ||||

3-7 |

4-7 |

5-7 |

6-7 |

7-7 | |||

3-8 |

4-8 |

5-8 |

6-8 |

7-8 |

8-8 | ||

3-9 |

4-9 |

5-9 |

6-9 |

7-9 |

8-9 |

9-9 | |

3-10 |

4-10 |

5-10 |

6-10 |

7-10 |

8-10 |

9-10 |

10-10 |

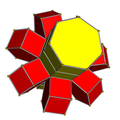

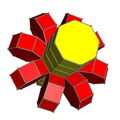

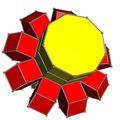

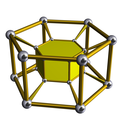

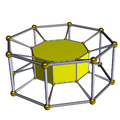

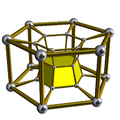

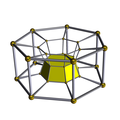

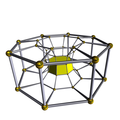

Perspective projections

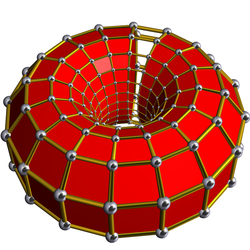

[edit]A cell-centered perspective projection makes a duoprism look like a torus, with two sets of orthogonal cells, p-gonal and q-gonal prisms.

|

|

| 6-prism | 6-6 duoprism |

|---|---|

| A hexagonal prism, projected into the plane by perspective, centered on a hexagonal face, looks like a double hexagon connected by (distorted) squares. Similarly a 6-6 duoprism projected into 3D approximates a torus, hexagonal both in plan and in section. | |

The p-q duoprisms are identical to the q-p duoprisms, but look different in these projections because they are projected in the center of different cells.

3-3 |

3-4 |

3-5 |

3-6 |

3-7 |

3-8 |

4-3 |

4-4 |

4-5 |

4-6 |

4-7 |

4-8 |

5-3 |

5-4 |

5-5 |

5-6 |

5-7 |

5-8 |

6-3 |

6-4 |

6-5 |

6-6 |

6-7 |

6-8 |

7-3 |

7-4 |

7-5 |

7-6 |

7-7 |

7-8 |

8-3 |

8-4 |

8-5 |

8-6 |

8-7 |

8-8 |

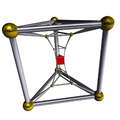

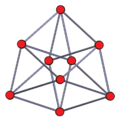

Orthogonal projections

[edit]Vertex-centered orthogonal projections of p-p duoprisms project into [2n] symmetry for odd degrees, and [n] for even degrees. There are n vertices projected into the center. For 4,4, it represents the A3 Coxeter plane of the tesseract. The 5,5 projection is identical to the 3D rhombic triacontahedron.

| Odd | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-3 | 5-5 | 7-7 | 9-9 | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [3] | [6] | [5] | [10] | [7] | [14] | [9] | [18] | ||||

| Even | |||||||||||

| 4-4 (tesseract) | 6-6 | 8-8 | 10-10 | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| [4] | [8] | [6] | [12] | [8] | [16] | [10] | [20] | ||||

Related polytopes

[edit]

The regular skew polyhedron, {4,4|n}, exists in 4-space as the n2 square faces of a n-n duoprism, using all 2n2 edges and n2 vertices. The 2n n-gonal faces can be seen as removed. (skew polyhedra can be seen in the same way by a n-m duoprism, but these are not regular.)

Duoantiprism

[edit]

Like the antiprisms as alternated prisms, there is a set of 4-dimensional duoantiprisms: 4-polytopes that can be created by an alternation operation applied to a duoprism. The alternated vertices create nonregular tetrahedral cells, except for the special case, the 4-4 duoprism (tesseract) which creates the uniform (and regular) 16-cell. The 16-cell is the only convex uniform duoantiprism.

The duoprisms ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , t0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, can be alternated into

, t0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, can be alternated into ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , ht0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, the "duoantiprisms", which cannot be made uniform in general. The only convex uniform solution is the trivial case of p=q=2, which is a lower symmetry construction of the tesseract

, ht0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, the "duoantiprisms", which cannot be made uniform in general. The only convex uniform solution is the trivial case of p=q=2, which is a lower symmetry construction of the tesseract ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , t0,1,2,3{2,2,2}, with its alternation as the 16-cell,

, t0,1,2,3{2,2,2}, with its alternation as the 16-cell, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , s{2}s{2}.

, s{2}s{2}.

The only nonconvex uniform solution is p=5, q=5/3, ht0,1,2,3{5,2,5/3}, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , constructed from 10 pentagonal antiprisms, 10 pentagrammic crossed-antiprisms, and 50 tetrahedra, known as the great duoantiprism (gudap).[2][3]

, constructed from 10 pentagonal antiprisms, 10 pentagrammic crossed-antiprisms, and 50 tetrahedra, known as the great duoantiprism (gudap).[2][3]

Ditetragoltriates

[edit]Also related are the ditetragoltriates or octagoltriates, formed by taking the octagon (considered to be a ditetragon or a truncated square) to a p-gon. The octagon of a p-gon can be clearly defined if one assumes that the octagon is the convex hull of two perpendicular rectangles; then the p-gonal ditetragoltriate is the convex hull of two p-p duoprisms (where the p-gons are similar but not congruent, having different sizes) in perpendicular orientations. The resulting polychoron is isogonal and has 2p p-gonal prisms and p2 rectangular trapezoprisms (a cube with D2d symmetry) but cannot be made uniform. The vertex figure is a triangular bipyramid.

Double antiprismoids

[edit]Like the duoantiprisms as alternated duoprisms, there is a set of p-gonal double antiprismoids created by alternating the 2p-gonal ditetragoltriates, creating p-gonal antiprisms and tetrahedra while reinterpreting the non-corealmic triangular bipyramidal spaces as two tetrahedra. The resulting figure is generally not uniform except for two cases: the grand antiprism and its conjugate, the pentagrammic double antiprismoid (with p = 5 and 5/3 respectively), represented as the alternation of a decagonal or decagrammic ditetragoltriate. The vertex figure is a variant of the sphenocorona.

k22 polytopes

[edit]The 3-3 duoprism, -122, is first in a dimensional series of uniform polytopes, expressed by Coxeter as k22 series. The 3-3 duoprism is the vertex figure for the second, the birectified 5-simplex. The fourth figure is a Euclidean honeycomb, 222, and the final is a paracompact hyperbolic honeycomb, 322, with Coxeter group [32,2,3], . Each progressive uniform polytope is constructed from the previous as its vertex figure.

| Space | Finite | Euclidean | Hyperbolic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Coxeter group |

A2A2 | E6 | =E6+ | =E6++ | |

| Coxeter diagram |

|||||

| Symmetry | [[32,2,-1]] | [[32,2,0]] | [[32,2,1]] | [[32,2,2]] | [[32,2,3]] |

| Order | 72 | 1440 | 103,680 | ∞ | |

| Graph |

|

|

|

∞ | ∞ |

| Name | −122 | 022 | 122 | 222 | 322 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained, Henry P. Manning, Munn & Company, 1910, New York. Available from the University of Virginia library. Also accessible online: The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained—contains a description of duoprisms (double prisms) and duocylinders (double cylinders). Googlebook

- ^ Jonathan Bowers - Miscellaneous Uniform Polychora 965. Gudap

- ^ http://www.polychora.com/12GudapsMovie.gif Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Animation of cross sections

References

[edit]- Regular Polytopes, H. S. M. Coxeter, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973, New York, p. 124.

- Coxeter, The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays, Dover Publications, 1999, ISBN 0-486-40919-8 (Chapter 5: Regular Skew Polyhedra in three and four dimensions and their topological analogues)

- Coxeter, H. S. M. Regular Skew Polyhedra in Three and Four Dimensions. Proc. London Math. Soc. 43, 33-62, 1937.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 26)

- N.W. Johnson: The Theory of Uniform Polytopes and Honeycombs, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1966

Duoprism

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Construction

Cartesian Product Basis

A duoprism is a 4-polytope constructed as the Cartesian product of two polygons and embedded in 4-dimensional Euclidean space. This product combines every point of the first polygon with every point of the second, forming a higher-dimensional analogue of prismatic figures. The term "duoprism" was introduced by H.S.M. Coxeter to describe such products of polygonal bases.[5][6] The explicit construction is given by the set where lies in the -plane and in the orthogonal -plane. This embedding ensures the resulting figure inherits the geometric structure from both components, with vertices corresponding to pairwise products of the polygons' vertices.[7][5] The Cartesian product serves as a fundamental operation in polytope geometry, extending lower-dimensional examples such as the product of a triangle and a line interval, which yields a triangular prism in 3-dimensional space. In general, the duoprism occupies 4 dimensions, though it degenerates to 3 dimensions if one polygon is a digon (a degenerate 2-gon equivalent to a line segment).[6][5] The resulting duoprism is convex if and only if both constituent polygons are convex, as the Cartesian product preserves convexity from its factors.[8]Elemental Composition

A duoprism, formed as the Cartesian product of an m-gon and an n-gon, consists of m n vertices, each corresponding to a unique pairing of a vertex from the m-gon with a vertex from the n-gon.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] The edges total 2 m n, comprising two sets: m n edges from the edges of the m-gon paired with vertices of the n-gon, and m n edges from the edges of the n-gon paired with vertices of the m-gon.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] The faces are of three types: n copies of the m-gon, arising from the full m-gon paired with each vertex of the n-gon; m copies of the n-gon, from the full n-gon paired with each vertex of the m-gon; and m n quadrilaterals, generated from each edge of the m-gon paired with each edge of the n-gon.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] Thus, the total number of faces is m + n + m n.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] The cells consist of n prisms with m-gonal bases, obtained by extruding the m-gon along each edge of the n-gon, and m prisms with n-gonal bases, from extruding the n-gon along each edge of the m-gon.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] The total number of cells is therefore m + n.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.] These counts satisfy the Euler characteristic for a convex 4-polytope, χ = V − E + F − C = 0. For instance, in the 3-3 duoprism, V = 9, E = 18, F = 15 (6 triangles and 9 quadrilaterals), and C = 6, yielding 9 − 18 + 15 − 6 = 0.[Coxeter, H.S.M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, p. 124.]Convexity and Uniformity

A duoprism, formed as the Cartesian product of two polygons and in orthogonal planes, inherits convexity from its base polygons. Specifically, the duoprism is convex if and only if both and are convex polygons, as the Cartesian product of convex sets in Euclidean space preserves convexity.[9] Uniform duoprisms arise when both base polygons are regular and share the same edge length, rendering the resulting 4-polytope vertex-transitive with uniform prismatic cells. In this case, the cells consist of 3-dimensional prisms, where each cell is formed by extruding one base polygon along the edges of the other, ensuring all cells are uniform polyhedra. If the base polygons are irregular, the duoprism remains well-defined and convex (provided the bases are convex) but loses uniformity, as the symmetry and transitivity properties degrade.[9][10] The symmetry group of a uniform duoprism is the direct product of the dihedral groups of the base polygons, acting independently on each 2-dimensional plane, with order . When , an additional symmetry arises from interchanging the identical factors, doubling the order to . Uniform duoprisms are vertex-transitive by construction but are cell-transitive (facet-transitive) only when , as the two types of prismatic cells become indistinguishable; otherwise, the distinct cell types prevent full cell-transitivity. They are not face-transitive in general, as there are distinct types of faces: the polygonal faces from the bases and the quadrilateral faces from edge products. Only in the special case m = n = 4, where the duoprism is the tesseract with all square faces, is it face-transitive.[9]Nomenclature and History

Naming Conventions

The standard nomenclature for duoprisms designates them as p-q duoprisms, where p and q (p ≤ q) denote the number of sides of the two regular polygons whose Cartesian product forms the polytope. This convention ensures uniqueness by ordering the factors, avoiding redundancy in naming isomorphic structures. For instance, the 3-4 duoprism arises from the product of a regular triangle and a square.[9] In symbolic notation, duoprisms employ the extended Schläfli symbol {p} × {q}, reflecting their construction as the product of two regular p-gons and q-gons; this differs from the standard Schläfli symbols for prisms ({p,3}) and antiprisms ({p,3/2}), which incorporate a triangular factor for extrusion along a line. The term "duoprism" itself, a contraction of "double prism," was coined by George Olshevsky in the 1990s during his compilation of a catalog of uniform polychora.[11] An alternative designation, "proprism," was introduced by John Horton Conway to describe the more general Cartesian product of two or more polytopes each of dimension at least two, encompassing duoprisms as a special case. Some notations occasionally conflate duoprisms with duopyramids, but the latter are the duals of duoprisms, formed instead by connecting corresponding vertices of the base polygons with edges.[9]Origins and Terminology Evolution

The roots of duoprism concepts trace back to 19th-century advancements in higher-dimensional geometry, particularly Ludwig Schläfli's work from 1850 to 1852, where he introduced the notion of polytopes (termed "polyschemes") as generalizations of polyhedra to n dimensions and developed Schläfli symbols for their classification.[12] Although Schläfli's contributions laid foundational groundwork for multidimensional polytopes, including the identification of six regular 4-polytopes, he did not explicitly address Cartesian products in the context of duoprisms.[12] In the 20th century, H. S. M. Coxeter's Regular Polytopes (first edition 1948, third edition 1973) explored prismatic constructions and Cartesian products of polytopes in higher dimensions, providing early theoretical support for such structures, though duoprisms as uniform 4-polytopes were not yet formalized.[5] Related early enumeration efforts included Norman W. Johnson's 1966 Ph.D. dissertation, The Theory of Uniform Polytopes and Honeycombs, which classified 75 non-prismatic uniform 4-polytopes under advisor Coxeter, while duoprisms form part of the infinite prismatic families explored in the broader theory.[13] The term "duoprism" was coined by George Olshevsky in the late 1990s, specifically during his 1997–2000 development of an online catalog of uniform polychora, where it denoted the Cartesian product of two polygons as a shorthand for "double prism."[14] In 2008, John H. Conway, in The Symmetries of Things, proposed the alternative term "proprism" for general Cartesian products of polytopes, emphasizing their isogonal (vertex-transitive) properties and integrating them into broader symmetry discussions.[15] Post-2000, duoprisms gained practical visibility through integration into visualization software such as Stella4D, which supports the generation and rendering of uniform duoprisms and antiduoprisms.[16] Duoprisms continue to hold potential applications within abstract polytope theory, particularly in studies of products and symmetries.Geometric Properties

Vertex, Edge, and Face Counts

In a uniform p-q duoprism, formed as the Cartesian product of regular p-gons and q-gons, the number of vertices is given by , as each vertex arises from pairing one vertex of the p-gon with one of the q-gon.[5] The number of edges is , consisting of edges from the p-gon directions (each vertex of the q-gon connected along the p-gon's edges) and from the q-gon directions.[5] The faces comprise three types: regular p-gonal faces (one for each vertex of the q-gon, spanning the full p-gon), regular q-gonal faces (one for each vertex of the p-gon, spanning the full q-gon), and square faces (arising from each edge of the p-gon paired with each edge of the q-gon, forming rectangular products that are squares in the uniform case).[5] Thus, the total number of faces is . The cells number , with q-gonal prisms (each q-gonal face extruded along the p-gon's edges) and p-gonal prisms (each p-gonal face extruded along the q-gon's edges); each such cell is uniform with square lateral faces.[5] These counts satisfy the Euler characteristic for 4-polytopes, . For instance, in the 3-3 duoprism, , , (6 triangles and 9 squares), and triangular prisms, yielding .[5] The 4-4 duoprism is the tesseract, with , , squares, and cubes.[5] The following table summarizes the element counts for a uniform p-q duoprism:| Element | Count | Components/Details |

|---|---|---|

| Vertices (V) | Product of vertices from each polygon | |

| Edges (E) | in p-direction + in q-direction | |

| Faces (F) | p-gons + q-gons + squares | |

| Cells (C) | q-gonal prisms + p-gonal prisms |