Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Five-dimensional space

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A five-dimensional (5D) space is a mathematical or physical concept referring to a space that has five independent dimensions. In physics and geometry, such a space extends the familiar three spatial dimensions plus time (4D spacetime) by introducing an additional degree of freedom, which is often used to model advanced theories such as higher-dimensional gravity, extra spatial directions, or connections between different points in spacetime.

Concepts

[edit]Concepts related to five-dimensional spaces include super-dimensional or hyper-dimensional spaces, which generally refer to any space with more than four dimensions. These ideas appear in theoretical physics, cosmology, and science fiction to explore phenomena beyond ordinary perception.

Important related topics include:

- 5-manifold — a generalization of a surface or volume to five dimensions.

- 5-cube — also called a penteract, a specific five-dimensional hypercube.

- Hypersphere — the generalization of a sphere to higher dimensions, including five-dimensional space.

- List of regular 5-polytopes — regular geometric shapes that exist in five-dimensional space.

- Four-dimensional space — a foundational step to understanding five-dimensional extensions.

Five-dimensional Euclidean geometry

[edit]5D Euclidean geometry designated by the mathematical sign: 5[1] is dimensions beyond two (planar) and three (solid). Shapes studied in five dimensions include counterparts of regular polyhedra and of the sphere.

Polytopes

[edit]In five or more dimensions, only three regular polytopes exist. In five dimensions, they are:

- The 5-simplex of the simplex family, {3,3,3,3}, with 6 vertices, 15 edges, 20 faces (each an equilateral triangle), 15 cells (each a regular tetrahedron), and 6 hypercells (each a 5-cell).

- The 5-cube of the hypercube family, {4,3,3,3}, with 32 vertices, 80 edges, 80 faces (each a square), 40 cells (each a cube), and 10 hypercells (each a tesseract).

- The 5-orthoplex of the cross polytope family, {3,3,3,4}, with 10 vertices, 40 edges, 80 faces (each a triangle), 80 cells (each a tetrahedron), and 32 hypercells (each a 5-cell).

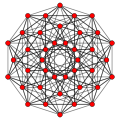

An important uniform 5-polytope is the 5-demicube, h{4,3,3,3} has half the vertices of the 5-cube (16), bounded by alternating 5-cell and 16-cell hypercells. The expanded or stericated 5-simplex is the vertex figure of the A5 lattice, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . It and has a doubled symmetry from its symmetric Coxeter diagram. The kissing number of the lattice, 30, is represented in its vertices.[2] The rectified 5-orthoplex is the vertex figure of the D5 lattice,

. It and has a doubled symmetry from its symmetric Coxeter diagram. The kissing number of the lattice, 30, is represented in its vertices.[2] The rectified 5-orthoplex is the vertex figure of the D5 lattice, ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . Its 40 vertices represent the kissing number of the lattice and the highest for dimension 5.[3]

. Its 40 vertices represent the kissing number of the lattice and the highest for dimension 5.[3]

| A5 | Aut(A5) | B5 | D5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5-simplex {3,3,3,3} |

Stericated 5-simplex |

5-cube {4,3,3,3} |

5-orthoplex {3,3,3,4} |

Rectified 5-orthoplex r{3,3,3,4} |

5-demicube h{4,3,3,3} |

Other five-dimensional geometries

[edit]The theory of special relativity makes use of Minkowski spacetime, a type of geometry that locates events in both space and time. The time dimension is mathematically distinguished from the spatial dimensions by a modification in the formula for computing the "distance" between events. Ordinary Minkowski spacetime has four dimensions in all, three of space and one of time. However, higher-dimensional generalizations of the concept have been employed in various proposals. Kaluza–Klein theory, a speculative attempt to develop a unified theory of gravity and electromagnetism, relied upon a spacetime with four dimensions of space and one of time.[4]

Geometries can also be constructed in which the coordinates are something other than real numbers. For example, one can define a space in which the points are labeled by tuples of 5 complex numbers. This is often denoted . In quantum information theory, quantum systems described by quantum states belonging to are sometimes called ququints.[5][6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Güler, Erhan (2024). "A helicoidal hypersurfaces family in five-dimensional euclidean space". Filomat. 38 (11). Bartın University: 3814 (4th para.;1st sent.). doi:10.2298/FIL2411813G.

- ^ "The Lattice A5". www.math.rwth-aachen.de.

- ^ Conway, John Horton; Sloane, Neil James Alexander (1999). Sphere Packings, Lattices and Groups (3rd ed.). p. 19. ISBN 978-0-387-98585-5.

- ^ Zwiebach, Barton (2004). A First Course in String Theory. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–16, 399. ISBN 0-521-83143-1.

- ^ Jain, Akalank; Shiroman, Prakash (2020). "Qutrit and ququint magic states". Physical Review A. 102 (4) 042409. arXiv:2003.07164. Bibcode:2020PhRvA.102d2409J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.102.042409.

- ^ Castelvecchi, Davide (2025-03-25). "Meet 'qudits': more complex cousins of qubits boost quantum computing". Nature. 640 (8057): 14–15. Bibcode:2025Natur.640...14C. doi:10.1038/d41586-025-00939-x. PMID 40133452. Retrieved 2025-05-11.

Further reading

[edit]- Wesson, Paul S. (1999). Space-Time-Matter, Modern Kaluza-Klein Theory. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-3588-7.

- Wesson, Paul S. (2006). Five-Dimensional Physics: Classical and Quantum Consequences of Kaluza-Klein Cosmology. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-256-661-9.

- Weyl, Hermann, Raum, Zeit, Materie, 1918. 5 edns. to 1922 ed. with notes by Jūrgen Ehlers, 1980. trans. 4th edn. Henry Brose, 1922 Space Time Matter, Methuen, rept. 1952 Dover. ISBN 0-486-60267-2.

External links

[edit]Five-dimensional space

View on GrokipediaFundamental Concepts

Definition and Generalization from Lower Dimensions

Five-dimensional space, denoted , is defined as the five-dimensional Euclidean vector space over the real numbers, comprising all ordered 5-tuples of real numbers that satisfy the axioms of a vector space under component-wise addition and scalar multiplication.[4] This structure generalizes the familiar lower-dimensional cases: one-dimensional space corresponds to the real line, to the Euclidean plane, and to three-dimensional space, each built upon the same algebraic foundation of vectors that can be added and scaled.[2] Extending this pattern, four-dimensional space introduces analogs like the tesseract (a four-dimensional hypercube), while five-dimensional space features the penteract as its hypercube counterpart, maintaining the core properties of closure under vector operations despite the increasing abstractness. These higher-dimensional spaces adhere to identical linear algebra rules as their lower-dimensional predecessors, allowing for consistent mathematical treatment, though they surpass direct human perceptual intuition rooted in three dimensions.[5] The axiomatic basis of ensures it forms a finite-dimensional vector space over the reals, which is complete as a normed space under the Euclidean metric, where every element is a linear combination of basis vectors, enabling the extension of geometric and analytical concepts from lower dimensions without alteration to the underlying operations.[4] A notable early popularization of higher-dimensional ideas appeared in Edwin Abbott's 1884 novella Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, which illustrates dimensional analogies through a two-dimensional society encountering the third dimension, a framework readily extendable to conceptualize five-dimensional space.[6]Coordinates and Basis Vectors

In five-dimensional Euclidean space, denoted , points are represented using Cartesian coordinates as ordered quintuples , where each is a real number specifying the position along the corresponding axis.[7] This coordinate system generalizes the familiar representations in lower dimensions, providing a direct means to locate any point in the space.[8] The standard orthonormal basis for consists of the vectors , , , , and .[9] These basis vectors are mutually orthogonal and each has unit length, forming a complete set that spans .[7] Due to their linear independence, any vector in can be uniquely expressed as a linear combination , where the coefficients are precisely the Cartesian coordinates of .[9] To represent points or vectors in bases other than the standard orthonormal one, a change of basis transformation is required, which can be effected via an invertible matrix relating the coordinates in the two systems.[8] For instance, oblique coordinates employ a basis where the vectors are linearly independent but not necessarily orthogonal, allowing for skewed axes while still spanning . A specific example arises in rotations, where the special orthogonal group SO(5) parameterizes all orientation-preserving linear transformations that preserve the standard basis structure up to rotation, represented by 5×5 orthogonal matrices with determinant 1.[10]Euclidean Geometry in Five Dimensions

Distance and Inner Product

In five-dimensional Euclidean space, denoted , the inner product provides the fundamental bilinear form that induces the standard metric structure. For two vectors and expressed in Cartesian coordinates, the Euclidean inner product is defined as This definition generalizes the dot product from lower dimensions and satisfies key properties: it is symmetric (), linear in the first argument, and positive definite (, with equality if and only if ).[11][12] The inner product induces a norm on , measuring the length of a vector from the origin, given by This Euclidean norm is positive definite and homogeneous ( for scalar ), enabling the definition of distance between any two points as the norm of their difference: The resulting metric satisfies the triangle inequality () and symmetry (), confirming as a metric space.[13][14] A significant consequence is the generalization of the Pythagorean theorem: if and are orthogonal (i.e., ), then This holds in as in lower dimensions, underpinning orthogonality in higher-dimensional geometry. An orthonormal basis for satisfies , where is the Kronecker delta (1 if , 0 otherwise), ensuring the coordinates align with the standard inner product.[15]Volumes and Hypersurface Areas

In five-dimensional Euclidean space, the volume (or 5-dimensional content) of a bounded region is defined as the Lebesgue measure which generalizes the familiar triple integral for 3D volumes. A fundamental example is the 5-simplex, the 5D analog of a tetrahedron, formed by six vertices in . Its volume is where is the matrix whose columns are the vectors . This formula arises from the fact that the simplex occupies of the parallelepiped spanned by those vectors, whose content is .[16] For the 5-dimensional unit ball, defined as using the Euclidean norm from the inner product, the volume is This follows from the general formula for the volume of an -ball of radius , derived via Gaussian integrals or recursive integration in hyperspherical coordinates, with the gamma function providing the dimensional generalization. For , .[17] The hypersurface area, or 4-dimensional content of the boundary of the 5-ball (the 4-sphere), is obtained from the general -dimensional surface area formula which relates to the ball volume by differentiation: . For , .[17] Cavalieri's principle extends to five dimensions, stating that if two regions in lie between parallel hyperplanes and have equal 4-dimensional cross-sectional measures at every position along the perpendicular direction, then they have equal 5-dimensional volumes; this aids in computing volumes by integrating lower-dimensional slices.[18]Regular Polytopes

In five-dimensional Euclidean space, there are exactly three regular convex 5-polytopes, generalizing the Platonic solids to higher dimensions. These consist of the infinite families that exist in all dimensions greater than or equal to five: the simplex, the hypercube, and the cross-polytope (orthoplex). This classification was established by Ludwig Schläfli in his 1852 work on higher-dimensional continuous manifolds and rigorously detailed by H. S. M. Coxeter, who showed that no additional regular convex polytopes exist beyond these families in five or more dimensions due to constraints on the dihedral angles and vertex figures satisfying the necessary inequalities for convexity. The 5-simplex, also known as the hexateron or 6-cell, has Schläfli symbol {3,3,3,3}. It is the convex hull of six mutually orthogonal points (or more generally, six points in general position with no four coplanar) and serves as the higher-dimensional analog of the tetrahedron. Its facets are five 4-simplices (5-cells). The 5-cube, or penteract, has Schläfli symbol {4,3,3,3} and extends the cube by adding a fifth dimension, with cubic 3-cells and tesseract 4-facets. The 5-orthoplex, or pentacross, has Schläfli symbol {3,3,3,4} and generalizes the octahedron, featuring tetrahedral 3-cells and 4-simplex 4-facets. The element counts for these polytopes can be derived systematically from their Schläfli symbols using Euler's formula for polytopes, (where is the number of -faces, including for the polytope itself), combined with incidence relations from the symbol (e.g., each edge shared by a fixed number of higher elements). For the 5-simplex, the counts follow binomial coefficients since it is the complete graph on six vertices generalized to higher faces. For the hypercube and orthoplex, the counts arise from choosing coordinate directions and sign combinations in the standard realizations. The following table summarizes the key elements:| Polytope | Schläfli Symbol | Vertices () | Edges () | 2-Faces () | 3-Cells () | 4-Facets () |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-Simplex | {3,3,3,3} | 6 | 15 | 20 (triangles) | 15 (tetrahedra) | 6 (5-cells) |

| 5-Cube | {4,3,3,3} | 32 | 80 | 80 (squares) | 40 (cubes) | 10 (tesseracts) |

| 5-Orthoplex | {3,3,3,4} | 10 | 40 | 80 (triangles) | 80 (tetrahedra) | 32 (5-cells) |

Non-Euclidean Geometries in Five Dimensions

Hyperbolic Five-space

Hyperbolic five-space, denoted , is the simply connected complete Riemannian manifold of dimension 5 with constant sectional curvature . This negative curvature distinguishes it from Euclidean five-space, where , leading to fundamentally different geometric properties such as the existence of infinitely many geodesics between points and exponential divergence of parallel geodesics. The space is non-compact and has infinite volume, enabling tessellations and structures impossible in positively curved or flat spaces. A common representation is the Poincaré ball model, where is realized as the open unit ball equipped with the Riemannian metric with . This conformal metric induces the constant curvature , and geodesics appear as circular arcs orthogonal to the boundary sphere. Another equivalent model is the hyperboloid model, embedding as the upper sheet of the two-sheeted hyperboloid in Minkowski space with the Lorentzian metric of signature (1,5). The hyperbolic metric is the restriction of this indefinite metric to the hyperboloid, preserving the curvature . These models are isometrically equivalent and facilitate computations in different contexts.[19] The negative curvature implies exponential volume growth: the volume of geodesic balls in satisfies as , contrasting with the polynomial growth in Euclidean space. Horoballs, bounded by horospheres (Euclidean null hypersurfaces at infinity), exhibit even faster divergence, with volumes between parallel horospheres growing exponentially in the distance between them, reflecting the space's hyperbolic divergence. This rapid expansion underpins applications in geometry and dynamics.[19] The geometry of supports a richer variety of regular polytopes than Euclidean space, where only three convex regular 5-polytopes exist. Negative curvature allows infinite tessellations, yielding more than six types of regular hyperbolic 5-polytopes, including ideal ones with vertices at infinity. These are classified by Schläfli symbols for which the associated Coxeter group is hyperbolic, enabling infinite families beyond the finite spherical and Euclidean cases. Examples include order-5 and order-6 apeirotope honeycombs, facilitating compactifications and orbifold constructions.Elliptic Five-space

Elliptic five-space refers to the five-dimensional manifold of constant positive curvature, modeled as the real projective space , which arises as the quotient of the five-sphere under the antipodal identification. Points in correspond to one-dimensional subspaces (lines through the origin) of , providing a projective interpretation where opposite points on are identified. This construction endows elliptic five-space with a compact topology without boundary, distinguishing it from the infinite extent of Euclidean or hyperbolic spaces.[20] The Riemannian metric on elliptic five-space is induced from the round metric on the unit sphere , defined by the line element subject to the constraint , quotiented by the antipodal map . This yields a metric of constant sectional curvature , ensuring uniform positive curvature throughout the space and resulting in finite total volume equal to half that of , specifically . Geodesics in this geometry are projections of great circles on , which close upon themselves after a length of , reflecting the identification that halves the periodicity of spherical geodesics.[21][22] Due to its compactness and positive curvature, elliptic five-space admits fewer regular tessellations than its hyperbolic counterpart, limited to finite configurations analogous to hemispherical polytopes on the sphere. These include the regular 5-simplex and cross-polytope, governed by finite reflection groups, serving as "hemispherical analogs" of Euclidean regulars like the hypercube, though the latter do not tessellate fully in this setting without adjustment. Seminal classifications highlight that only three convex regular polytopes exist in five dimensions and higher, with elliptic tessellations inheriting these via the quotient, emphasizing symmetry under the orthogonal group .[23][24]Visualizations and Projections

Dimensional Analogy and Intuition

To develop intuition for five-dimensional space, one can extend analogies from lower dimensions, much like the classic depiction in Edwin Abbott's Flatland, where two-dimensional beings inhabit a plane and perceive three-dimensional objects as fleeting lines or shapes crossing their world, representing an incomprehensible "up/down" direction orthogonal to their flat existence.[25] This progression continues to four dimensions, where three-dimensional observers might experience a fourth spatial direction as "ana" (toward) or "kata" (from), terms coined by Charles Howard Hinton to describe motion along this extra axis, analogous to how height extends beyond length and width.[26] Extending further, five-dimensional space introduces yet another orthogonal direction, which a four-dimensional entity would perceive as an additional perpendicular axis, building on the same hierarchical intuition of successive orthogonal extensions. A useful way to grasp five-dimensional structures is through cross-sections and shadows, where intersecting a higher-dimensional object with a lower-dimensional hyperplane yields familiar lower-dimensional forms, similar to how slicing a four-dimensional tesseract (hypercube) produces varying three-dimensional cubes or polyhedra, or casting its shadow onto a two-dimensional plane results in distorted, unfolding squares.[27] In five dimensions, such a hyperslice might reveal four-dimensional polytopes, while projections or shadows could appear as evolving three-dimensional solids to human observers, emphasizing how partial intersections obscure the full structure, much like a three-dimensional sphere passing through a two-dimensional plane appears as a circle that grows and shrinks.[28] From an intrinsic perspective, inhabitants of five-dimensional space would experience their environment seamlessly within those dimensions, unaware of any "extra" unless encountering phenomena from even higher realms, akin to how Flatland's residents navigate their plane without sensing depth until disrupted by a three-dimensional intruder.[25] Extrinsically, however, lower-dimensional observers like humans might only access slices or projections, highlighting the disconnect between full dimensionality and reduced perceptions.[27] Human cognition faces significant challenges in visualizing five-dimensional space, as our brains are evolutionarily tuned to three spatial dimensions, limiting direct mental imagery beyond this and relying on abstract metaphors, such as treating time as a fourth dimension in relativity, though pure spatial five-dimensionality lacks such a temporal proxy and remains counterintuitive.[29] This perceptual boundary often leads to reliance on analogies and computational aids rather than innate comprehension, underscoring the abstract nature of higher geometry.[30]Orthogonal and Perspective Projections

Orthogonal projections provide a method to map points from five-dimensional Euclidean space onto a three-dimensional subspace , preserving lengths and angles within the target subspace. For a point , the projection is computed using a matrix whose rows form an orthonormal basis for the target subspace, yielding the projected point . This ensures the projection is orthogonal, meaning the vector is perpendicular to the subspace spanned by the rows of . A simple example is the coordinate projection onto the first three axes, where , ignoring and while retaining . Such projections are linear transformations that minimize the Euclidean distance to the subspace and are widely used in computational geometry for dimensionality reduction.[31] Perspective projections, in contrast, introduce depth-dependent scaling to simulate viewing from a central point, mapping five-dimensional points to a three-dimensional hyperplane through central projection. In projective space , points are represented in homogeneous coordinates as , where the six components allow for the projective equivalence for . The projection onto a hyperplane, say defined by (with center of projection at the origin), dehomogenizes by dividing by the last coordinate, yielding affine coordinates in the chosen subspace after embedding into . This is achieved via a transformation matrix in homogeneous coordinates, generalizing the three-dimensional case where a matrix incorporates the perspective divide. Perspective projections preserve straight lines but distort sizes based on distance from the center, with farther points appearing smaller.[32] Shadow projections analogize these techniques to casting "shadows" of five-dimensional objects onto lower-dimensional screens. Orthogonal shadow projections use parallel rays perpendicular to the projection hyperplane, equivalent to the matrix-based orthogonal method and producing minimal distortion for objects aligned with the viewing axes. Perspective shadow projections employ converging rays from a point source, mimicking central projection and introducing foreshortening that emphasizes depth but can warp structures, particularly for convex five-dimensional polytopes like the penteract (five-dimensional hypercube). For the penteract, orthogonal projections yield symmetric but collapsed wireframes in , while perspective versions distort edges near the "horizon," creating illusory depth and highlighting rotational symmetries, as seen in stereographic variants that map from a hypersphere to preserve angles. These distortions aid in revealing internal connectivity but require careful viewpoint selection to avoid self-intersections in the projected image.[33] Software tools facilitate rendering these projections for five-dimensional objects. Mathematica supports high-dimensional visualizations through functions likeProjection and ListPointPlot3D applied to projected coordinates, enabling interactive 5D-to-3D mappings via Manipulate for exploring rotations and viewpoints. Similarly, POV-Ray, a ray-tracing engine, generates photorealistic renders of projected 5D polytopes by scripting orthogonal or perspective transformations in its scene description language. These tools often combine with unfolding techniques for comprehensive views.[34][35]

Unfolding provides an alternative visualization by "nets" that lay out the boundary of a five-dimensional polytope onto lower-dimensional flats without overlap. Analogous to nets of three-dimensional polyhedra like the cube, a 5D net decomposes the 4D facets (cells) along ridges into a connected 4D "sheet," which can then be further projected or sliced into 3D or 2D for display. For the penteract, such unfoldings reveal its 10 tesseract cells arranged without crossing, though ensuring non-overlapping embeddings in 4D remains computationally intensive due to the polytope's symmetry. These nets preserve metric properties locally and are useful for verifying topological structure in projections.[36]