Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vertex figure

View on Wikipedia

In geometry, a vertex figure, broadly speaking, is the figure exposed when a corner of a general n-polytope is sliced off.

Definitions

[edit]

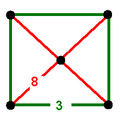

Take some corner or vertex of a polyhedron. Mark a point somewhere along each connected edge. Draw lines across the connected faces, joining adjacent points around the face. When done, these lines form a complete circuit, i.e. a polygon, around the vertex. This polygon is the vertex figure.

More precise formal definitions can vary quite widely, according to circumstance. For example Coxeter (e.g. 1948, 1954) varies his definition as convenient for the current area of discussion. Most of the following definitions of a vertex figure apply equally well to infinite tilings or, by extension, to space-filling tessellation with polytope cells and other higher-dimensional polytopes.

As a flat slice

[edit]Make a slice through the corner of the polyhedron, cutting through all the edges connected to the vertex. The cut surface is the vertex figure (a plane figure). This is perhaps the most common approach, and the most easily understood. Different authors make the slice in different places. Wenninger (2003) cuts each edge a unit distance from the vertex, as does Coxeter (1948). For uniform polyhedra the Dorman Luke construction cuts each connected edge at its midpoint. Other authors make the cut through the vertex at the other end of each edge.[1][2]

For an irregular polyhedron, cutting all edges incident to a given vertex at equal distances from the vertex may produce a figure that does not lie in a plane. A more general approach, valid for arbitrary convex polyhedra, is to make the cut along any plane which separates the given vertex from all the other vertices, but is otherwise arbitrary. This construction determines the combinatorial structure of the vertex figure, similar to a set of connected vertices (see below), but not its precise geometry; it may be generalized to convex polytopes in any dimension. However, for non-convex polyhedra, there may not exist a plane near the vertex that cuts all of the faces incident to the vertex.

As a spherical polygon

[edit]Cromwell (1999) forms the vertex figure by intersecting the polyhedron with a sphere centered at the vertex, small enough that it intersects only edges and faces incident to the vertex. This can be visualized as making a spherical cut or scoop, centered on the vertex. The cut surface or vertex figure is thus a spherical polygon marked on this sphere. One advantage of this method is that the shape of the vertex figure is fixed (up to the scale of the sphere), whereas the method of intersecting with a plane can produce different shapes depending on the angle of the plane. Additionally, this method works for non-convex polyhedra.

As the set of connected vertices

[edit]Many combinatorial and computational approaches (e.g. Skilling, 1975) treat a vertex figure as the ordered (or partially ordered) set of points of all the neighboring (connected via an edge) vertices to the given vertex.

Abstract definition

[edit]In the theory of abstract polytopes, the vertex figure at a given vertex V comprises all the elements which are incident on the vertex; edges, faces, etc. More formally it is the (n−1)-section Fn/V, where Fn is the greatest face.

This set of elements is elsewhere known as a vertex star. The geometrical vertex figure and the vertex star may be understood as distinct realizations of the same abstract section.

General properties

[edit]A vertex figure of an n-polytope is an (n−1)-polytope. For example, a vertex figure of a polyhedron is a polygon, and the vertex figure for a 4-polytope is a polyhedron.

In general a vertex figure need not be planar.

For nonconvex polyhedra, the vertex figure may also be nonconvex. Uniform polytopes, for instance, can have star polygons for faces and/or for vertex figures.

Isogonal figures

[edit]Vertex figures are especially significant for uniforms and other isogonal (vertex-transitive) polytopes because one vertex figure can define the entire polytope.

For polyhedra with regular faces, a vertex figure can be represented in vertex configuration notation, by listing the faces in sequence around the vertex. For example 3.4.4.4 is a vertex with one triangle and three squares, and it defines the uniform rhombicuboctahedron.

If the polytope is isogonal, the vertex figure will exist in a hyperplane surface of the n-space.

Constructions

[edit]From the adjacent vertices

[edit]By considering the connectivity of these neighboring vertices, a vertex figure can be constructed for each vertex of a polytope:

- Each vertex of the vertex figure coincides with a vertex of the original polytope.

- Each edge of the vertex figure exists on or inside of a face of the original polytope connecting two alternate vertices from an original face.

- Each face of the vertex figure exists on or inside a cell of the original n-polytope (for n > 3).

- ... and so on to higher order elements in higher order polytopes.

Dorman Luke construction

[edit]For a uniform polyhedron, the face of the dual polyhedron may be found from the original polyhedron's vertex figure using the "Dorman Luke" construction.

Regular polytopes

[edit]

If a polytope is regular, it can be represented by a Schläfli symbol and both the cell and the vertex figure can be trivially extracted from this notation.

In general a regular polytope with Schläfli symbol {a,b,c,...,y,z} has cells as {a,b,c,...,y}, and vertex figures as {b,c,...,y,z}.

- For a regular polyhedron {p,q}, the vertex figure is {q}, a q-gon.

- Example, the vertex figure for a cube {4,3}, is the triangle {3}.

- For a regular 4-polytope or space-filling tessellation {p,q,r}, the vertex figure is {q,r}.

- Example, the vertex figure for a hypercube {4,3,3}, the vertex figure is a regular tetrahedron {3,3}.

- Also the vertex figure for a cubic honeycomb {4,3,4}, the vertex figure is a regular octahedron {3,4}.

Since the dual polytope of a regular polytope is also regular and represented by the Schläfli symbol indices reversed, it is easy to see the dual of the vertex figure is the cell of the dual polytope. For regular polyhedra, this is a special case of the Dorman Luke construction.

An example vertex figure of a honeycomb

[edit]

The vertex figure of a truncated cubic honeycomb is a nonuniform square pyramid. One octahedron and four truncated cubes meet at each vertex form a space-filling tessellation.

| Vertex figure: A nonuniform square pyramid |  Schlegel diagram |

Perspective |

| Created as a square base from an octahedron |  (3.3.3.3) | |

| And four isosceles triangle sides from truncated cubes |  (3.8.8) |

Edge figure

[edit]

Related to the vertex figure, an edge figure is the vertex figure of a vertex figure.[3] Edge figures are useful for expressing relations between the elements within regular and uniform polytopes.

An edge figure will be a (n−2)-polytope, representing the arrangement of facets around a given edge. Regular and single-ringed coxeter diagram uniform polytopes will have a single edge type. In general, a uniform polytope can have as many edge types as active mirrors in the construction, since each active mirror produces one edge in the fundamental domain.

Regular polytopes (and honeycombs) have a single edge figure which is also regular. For a regular polytope {p,q,r,s,...,z}, the edge figure is {r,s,...,z}.

In four dimensions, the edge figure of a 4-polytope or 3-honeycomb is a polygon representing the arrangement of a set of facets around an edge. For example, the edge figure for a regular cubic honeycomb {4,3,4} is a square, and for a regular 4-polytope {p,q,r} is the polygon {r}.

Less trivially, the truncated cubic honeycomb t0,1{4,3,4}, has a square pyramid vertex figure, with truncated cube and octahedron cells. Here there are two types of edge figures. One is a square edge figure at the apex of the pyramid. This represents the four truncated cubes around an edge. The other four edge figures are isosceles triangles on the base vertices of the pyramid. These represent the arrangement of two truncated cubes and one octahedron around the other edges.

See also

[edit]- Simplicial link - an abstract concept related to vertex figure.

- List of regular polytopes

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Coxeter, H. et al. (1954).

- ^ Skilling, J. (1975).

- ^ Klitzing: Vertex figures, etc.

Bibliography

[edit]- H. S. M. Coxeter, Regular Polytopes, Hbk (1948), ppbk (1973).

- H.S.M. Coxeter (et al.), Uniform Polyhedra, Phil. Trans. 246 A (1954) pp. 401–450.

- P. Cromwell, Polyhedra, CUP pbk. (1999).

- H.M. Cundy and A.P. Rollett, Mathematical Models, Oxford Univ. Press (1961).

- J. Skilling, The Complete Set of Uniform Polyhedra, Phil. Trans. 278 A (1975) pp. 111–135.

- M. Wenninger, Dual Models, CUP hbk (1983) ppbk (2003).

- The Symmetries of Things 2008, John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5, (p. 289 Vertex figures).

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Vertex figure". MathWorld.

- Olshevsky, George. "Vertex figure". Glossary for Hyperspace. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

- Vertex Figures

- Consistent Vertex Descriptions

Vertex figure

View on GrokipediaDefinitions

Planar slice definition

The planar slice definition of the vertex figure for a polytope describes it as the cross-section obtained by intersecting the polytope with a hyperplane positioned close to but not passing through the specified vertex. For a convex polytope in Euclidean space, this hyperplane is typically chosen parallel to the supporting hyperplane at the vertex , which touches only at and separates from all other vertices, then offset slightly inward by a small positive to ensure the intersection avoids degeneracy and captures the adjacent structure.[3][4] In cases where is centered at the origin, the supporting hyperplane can be taken perpendicular to the radius vector from the center to , providing a symmetric slice that reflects the local radial geometry.[5] Mathematically, if is an -dimensional polytope and is the supporting hyperplane at with , the vertex figure is the intersection for sufficiently small . This yields an -dimensional polytope whose face lattice is isomorphic to the interval in the face lattice of , effectively encoding the combinatorial types of faces incident to .[3] The resulting does not include itself, thereby highlighting the local geometry surrounding the vertex through the arrangement of edges, faces, and higher-dimensional elements emanating from it.[4] In two dimensions, for a convex polygon, the vertex figure at a vertex reduces to the line segment formed by the intersection points on the two adjacent edges, akin to the link of those edges and representing the angular span at the vertex. For example, in a square, this segment has length equal to the side length times , illustrating the 45-degree dihedral contribution.[2] In three dimensions, for a polyhedron, the slice intersects the faces meeting at the vertex, producing a polygon whose sides correspond to the intersections with those faces and vertices to the intersections with the edges from the original vertex; for a cube, this yields an equilateral triangle reflecting the three perpendicular faces.[3] This approach provides a direct Euclidean visualization of the vertex configuration, distinct from alternatives like the stereographic projection onto a sphere.[5]Spherical polygon definition

The spherical polygon definition of the vertex figure arises from intersecting the unit sphere centered at a given vertex of the polytope with rays emanating from that vertex along each incident edge. These intersection points serve as the vertices of a spherical polygon on the unit sphere, with the sides consisting of great circle arcs that connect consecutive points in the cyclic order determined by the arrangement of edges around the vertex. Each such arc corresponds to the plane angle (face angle) at the vertex within the polyhedral face bounded by the two edges. The length θ of each great circle arc, representing a side of the spherical polygon, equals the angle between the directions of the two adjacent edges defining that face angle. If u and v are unit vectors along these adjacent edges, then θ is given by the equation which follows directly from the geometric definition of the dot product as the cosine of the angle between two unit vectors. To arrive at this, normalize the edge direction vectors to unit length (dividing by their magnitudes), then compute the dot product; the inverse cosine yields θ in radians, ensuring the spherical side length reflects the intrinsic angular measure independent of edge lengths. A key aspect of this construction is that the interior angles of the spherical polygon equal the dihedral angles between consecutive faces meeting at the vertex, thereby encoding the polytope's local metric structure—specifically, the angles between adjacent face planes—directly into the polygon's geometry. This intrinsic representation on the sphere facilitates analysis of angular deficits or excesses, which relate to curvature properties at the vertex in both Euclidean and non-Euclidean embeddings of polytopes. This spherical definition remains independent of the overall size of the polytope, as scaling the polytope scales the sphere proportionally but the unit normalization preserves all angular measures. It extends to non-convex polytopes where the local star at the vertex is simply connected, maintaining the topological structure of the vertex link while capturing potentially re-entrant angular configurations without altering the fundamental spherical topology.Graph-theoretic definition

In graph-theoretic terms, the vertex figure at a vertex of a polytope is defined as the induced subgraph of the 1-skeleton (edge graph) of on the set of vertices adjacent to .[6] This induced subgraph constitutes the 1-skeleton of the combinatorial vertex figure, capturing the local connectivity among the neighbors of .[6] In general, for a -dimensional polytope, this graph is isomorphic to the 1-skeleton of a -dimensional polytope.[6] For a 3-dimensional polyhedron, the vertex figure at a vertex of degree is a -gon, and its graph is the cycle graph , obtained by connecting the neighboring vertices in the cyclic order determined by the faces incident to . This cycle reflects the link of edges surrounding the vertex, with no additional edges (chords) in the induced subgraph for convex polyhedra. In higher dimensions, the structure extends accordingly: for simple polytopes, where each vertex has degree , the vertex figure is a -simplex, and its 1-skeleton is the complete graph on the neighboring vertices. More complex polytopes may yield non-simplicial vertex figures with graphs that are not complete or cyclic.[6] A representative example is the cube, a 3-dimensional simple polyhedron where each vertex has degree 3; the induced subgraph on its three neighbors forms a triangle, isomorphic to the cycle graph .Abstract definition

In the theory of abstract polytopes, the vertex figure at a vertex of an -polytope is the abstract -polytope whose elements are derived from those of incident to , specifically the quotient . The vertices (0-faces) of this vertex figure are the edges (1-faces) of incident to ; its edges (1-faces) are the 2-faces of containing ; its 2-faces are the 3-faces of containing ; and, in general, its -faces are the -faces of containing , for , with incidences preserved by inclusion in .[7] This structure is isomorphic to the facet of the dual polytope corresponding to the face of opposite to (when such an opposite face exists, as in centrally symmetric polytopes), or more generally to the quotient of by the vertex , capturing the local combinatorial neighborhood around in the face lattice. In the context of Coxeter groups, where is a regular abstract polytope realized as the orbit polytope of a Coxeter group generated by reflections , the automorphism group of the vertex figure at is the parabolic subgroup generated by the reflections in corresponding to the hyperplanes (or walls) meeting at .[8] The mathematical structure of the vertex figure can be represented via the incidence matrix of the poset consisting of all faces of strictly containing , ranked relative to (the vertex's star in the face poset, with ranks shifted by -1), or equivalently as the link of in the order complex of . Its 1-skeleton is the graph-theoretic vertex figure, connecting incident edges that lie in a common 2-face.[7]Properties

Isogonal conjugates

A vertex figure is isogonal if its symmetry group acts transitively on its vertices, meaning all vertices of the figure are equivalent under the symmetries of the polytope. This vertex-transitivity ensures a high degree of uniformity in how the figure connects the adjacent faces of the original polytope. Such isogonal vertex figures are a hallmark of uniform polytopes, where the same arrangement of regular faces meets at every vertex, allowing the symmetry group to map any vertex of the vertex figure to any other.[9] The polar reciprocal of a vertex figure refers to its polar reciprocal representation on the sphere, which interchanges the roles of vertices and edges while preserving the incidence relations with the faces of the polytope. In this transformation, the vertices of the reciprocal correspond to the edges of the original vertex figure, and the edges of the reciprocal correspond to the original vertices, resulting in a new spherical polygon whose arc lengths (edge lengths) differ from those of the original unless the figure is self-dual. This reciprocation maintains the overall topological structure but adjusts the metric properties to reflect the reciprocal geometry, providing insight into the dual relationships within the polytope. For uniform polytopes, this process highlights how symmetry is redistributed between primal and dual forms.[10] In Archimedean solids, a subset of uniform polyhedra characterized by regular faces and identical vertex configurations, the vertex figures are regular polygons, inherently ensuring isogonality through full edge- and vertex-transitivity. These regular vertex figures, such as equilateral triangles or squares, simplify the analysis of local symmetry at each vertex.[9] The terminology "isogonal" for vertex-transitive figures, including their edge-transitive vertex figures, was introduced by H.S.M. Coxeter in his foundational work during the 1930s, building on earlier enumerations of polyhedra but providing a more complete symmetry framework that older sources lacked.[9]Dihedral angle relations

In the spherical vertex figure of a polytope, the side lengths of the polygon correspond to the planar angles at the vertex formed by the edges of the adjacent faces, while the interior vertex angles of the figure equal the dihedral angles between those faces.[11] This duality arises from the geometry of the unit sphere centered at the vertex, where great-circle arcs represent the intersections with the face planes, preserving the angular measures from the original polytope.[11] For a dihedral angle between two adjacent faces meeting at an edge from the vertex, is precisely the interior angle at the corresponding vertex of the spherical polygon, where the two arcs (sides) associated with those faces intersect.[11] This direct mapping holds for both convex and star polytopes, provided the vertex figure remains a well-defined spherical polygon without self-intersections that obscure the angles.[11] The encoding of dihedral angles within the vertex figure enables their computation solely from the figure's geometry, independent of the full polytope structure, which proves valuable for irregular or higher-dimensional cases where explicit coordinate-based methods are cumbersome.[11] In regular polytopes, uniformity ensures all dihedral angles are identical, yielding a regular spherical vertex figure with equal sides and angles.[11]Dimensionality and homology

The vertex figure of an n-polytope is itself an (n-1)-polytope, thereby reducing the dimensionality by one relative to the original polytope. This follows from the standard construction, where the vertex figure arises as the intersection of the n-polytope with a supporting hyperplane that separates the chosen vertex from the rest of the polytope, yielding a convex body of one lower dimension.[12] In the abstract poset sense, the vertex figure corresponds to the open interval in the face lattice from the vertex to the facets incident to it, preserving the combinatorial structure while lowering the rank by one.[3] Homologically, the vertex figure can be understood as the boundary of the link of the vertex within the cell complex of the polytope. The link itself is combinatorially equivalent to the vertex figure, and for convex polytopes, this link is a homology (n-2)-sphere, reflecting the local topology around the vertex. The Euler characteristic of this link is given by , which is independent of the specific degree of the vertex but constrains the overall face counts; the degree of the vertex, equal to the number of incident edges, corresponds to the number of vertices in the vertex figure, influencing higher face numbers through relations like the Dehn-Sommerville equations.[3][12] For simply connected polytopes, the vertex figure exhibits strong connectivity properties, being (n-3)-connected, meaning its homotopy groups vanish up to dimension n-3. In three dimensions, the vertex figure takes the form of a spherical polygon, which is homotopy equivalent to a circle . This spherical realization underscores its role as a model for in higher dimensions.[13] In modern algebraic topology, vertex figures connect to broader constructions such as the Davis-Januszkiewicz spaces associated to simple polytopes, where the homology of the vertex figure's boundary complex informs the cohomology of moment-angle complexes built over the polytope's face lattice. These spaces generalize toric varieties and reveal torsion-free cohomology rings isomorphic to Stanley-Reisner rings, linking local vertex topology to global invariants.[14]Constructions

Adjacent vertices method

The adjacent vertices method provides a straightforward geometric approach to constructing the vertex figure of a polytope embedded in Euclidean space. Begin by selecting a vertex and identifying all vertices adjacent to it, meaning those connected directly by an edge. These adjacent vertices serve as the vertices of the vertex figure. Next, determine the cyclic order of these adjacent vertices around , which is dictated by their sequence in the faces incident to or equivalently by the link in the 1-skeleton of the polytope. Connect consecutive vertices in this cyclic order with straight-line segments to form the edges of the figure, yielding a polygonal boundary in three dimensions or a higher-dimensional analogue in greater dimensions.[15] This construction relies on the Euclidean realization of the polytope, where the lengths of the vertex figure's edges are precisely the Euclidean distances between pairs of consecutive adjacent vertices in the original embedding. For instance, in a polyhedron, each such edge lies within one of the faces incident to , capturing the local geometry around the vertex. In higher dimensions, the resulting figure is the boundary complex formed by these connections, often realized as the convex hull of the adjacent vertices.[16] In the case of polyhedra, the method produces a polygon whose vertices coincide with the adjacent vertices of the original polyhedron. If the vertex is "small"—typically meaning the edges incident to are short relative to the scale of the incident faces, rendering the adjacent vertices nearly coplanar—the resulting polygon is approximately planar without further adjustment. However, for vertices where the incident solid angle is larger, the polygon may be skew (non-planar), necessitating an orthogonal projection onto a suitable plane, such as one perpendicular to the inward normal at , to obtain a planar representation that preserves angles and connectivity.[15] The positions of the vertex figure's vertices can be expressed relative to using vector notation: if is translated to the origin, each adjacent vertex has position vector . These may be adjusted via affine linear combinations, such as scaling along rays from (e.g., for small ) to simulate a cross-section near , or normalized using barycentric coordinates within the star of to embed the figure in a standard (n-1)-dimensional affine subspace. For example, in barycentric terms with respect to the facets incident to , the coordinates emphasize the combinatorial weights around .[16]Dorman-Luke construction

The Dorman-Luke construction is a geometric method for deriving the facets of a dual polytope from the vertex figure of the original polytope, particularly suited for uniform polytopes and honeycombs. It applies to polyhedra with a midsphere (intersphere tangent to all edges) where the vertex figure is cyclic, allowing the construction of tangential polygons that form the faces of the dual. This approach is valuable for uniform cases, as described in Cundy and Rollett (1989).[10][17] For uniform polyhedra, the vertex figure is formed by connecting the midpoints of the edges incident to the vertex. The dual face is then obtained by constructing the tangential polygon circumscribing this vertex figure, with vertices corresponding to the points of tangency on the midsphere. This method extends to higher dimensions for uniform polytopes, facilitating the derivation of dual structures without direct spherical computations, though it relies on first obtaining the vertex figure coordinates via other means, such as the adjacent vertices method.[10]Coxeter-Dynkin diagram derivation

The derivation of a vertex figure using Coxeter-Dynkin diagrams relies on the structure of the underlying Coxeter group, which encodes the symmetries of the polytope or tiling as a reflection group. In this approach, the diagram's nodes represent the generating reflections, with edges labeled by the orders of products of adjacent reflections. To obtain the vertex figure at a specific vertex, identify the node corresponding to the reflection hyperplane through that vertex (often marked as the "ringed" node in uniform polytope notations). Removing this node and its incident edges yields the Coxeter-Dynkin diagram of the parabolic subgroup generated by the remaining reflections, which is the stabilizer of the vertex in the Coxeter group action. This parabolic subgroup's diagram describes the symmetry group of the vertex figure, realized as a spherical polytope on the unit sphere centered at the vertex.[18] For irreducible Coxeter groups, the vertex figure corresponds precisely to the spherical polytope associated with this parabolic subgroup, as the link of the vertex in the Coxeter complex is the complex of the stabilizer. The removal of the node reduces the rank by one, producing a diagram for an (n-1)-dimensional spherical polytope, where n is the original dimension. This method highlights the recursive nature of polytope symmetries, where subdiagrams govern local structures like faces and edges. In the context of root systems underlying these groups, the vertex figure at a vertex corresponding to a simple root α_i is combinatorially equivalent to the polytope defined by the reduced root system excluding α_i, confirming the node-removal process.[18] A concrete illustration arises in regular polytopes, denoted by Schläfli symbols {p, q, r, ..., s}. The full symbol {p_1, p_2, ..., p_n} describes an n-dimensional regular polytope, and its vertex figure is the regular (n-1)-polytope {p_2, p_3, ..., p_n}, obtained by truncating the first entry in the corresponding linear Coxeter-Dynkin diagram (a path graph). For instance, the 4-dimensional 120-cell {5,3,3} has vertex figure the tetrahedron {3,3}. This recursive property holds because the stabilizer of a vertex excludes the initial reflection, leaving the subgroup for the remaining symbol.[19] The distinction between finite and affine Coxeter groups is particularly relevant for tilings and honeycombs. Finite irreducible Coxeter groups yield spherical vertex figures, as all parabolic subgroups are also finite and act on spheres. In contrast, affine Coxeter groups, which govern Euclidean tilings and honeycombs, are infinite but virtually abelian; removing a node typically produces a finite (spherical) parabolic subgroup, ensuring the vertex figure is a compact spherical polytope despite the ambient space being flat. For example, in the affine diagram for the square tiling (affine A_3, a square with nodes), excising the vertex node results in a finite dihedral subgroup diagram, corresponding to a spherical digon vertex figure, though realized as a line segment in the link. This ensures vertex figures remain finite and bounded even in infinite constructions.[18]Examples

In uniform polyhedra

In uniform polyhedra, which include the Platonic solids, Archimedean solids, prisms, antiprisms, and certain star polyhedra, the vertex figure is identical at every vertex due to vertex-transitivity, and it takes the form of an equilateral polygon whose number of sides equals the number of edges incident to the vertex. This polygon arises from connecting the midpoints of those incident edges, providing a cross-section of the solid angle at the vertex. The specific shape and properties of the vertex figure reflect the arrangement of regular faces meeting at the vertex, as captured in the polyhedron's vertex configuration notation (e.g., 3.4.3.4 for the cuboctahedron).[20][9] For the Platonic solids, the vertex figures are regular polygons, directly linked to the second parameter q in their Schläfli symbol {p, q}, where p denotes the number of sides per face and q the number of faces meeting at each vertex. A representative example is the cube {4,3}, where three square faces meet at each vertex; the vertex figure is thus a regular equilateral triangle, with each side length equal to the cube's edge length divided by √2. Similarly, the regular dodecahedron {5,3} has a regular triangular vertex figure, arising from three pentagonal faces per vertex. These figures are planar and convex, illustrating the uniformity and symmetry of Platonic solids.[21][22][23] Among the Archimedean solids, vertex figures are equilateral but generally not equiangular, resulting in irregular polygons that still maintain equal edge lengths due to the uniform edge structure. For instance, in the truncated tetrahedron (Schläfli symbol t{3,3} or vertex configuration 3.6.6), one triangular face and two hexagonal faces meet at each vertex of degree 3; the vertex figure is an isosceles triangle with side lengths in the ratio 1 : √3 : √3 (assuming unit edge length), where the unequal angles correspond to the differing face types adjacent to each edge from the vertex. Visual diagrams of such figures for Platonic and Archimedean solids often depict these polygons inscribed in a circle or superimposed on the polyhedron to highlight their role in determining local geometry and overall symmetry.[24][25][26] In non-convex uniform polyhedra, such as the Kepler-Poinsot solids, the density (winding number) of the face arrangement around a vertex can cause the vertex figure to be a star polygon rather than a simple planar one, affecting its embedding and intersection properties; however, for convex uniform polyhedra, the figures remain simple and planar. This connection to Schläfli symbols and vertex configurations underscores how vertex figures encode the combinatorial and metric structure of uniform polyhedra.[9][20]In tilings and honeycombs

In Euclidean plane tilings, the vertex figure of the regular square tiling {4,4} is a square {4}, illustrating how four squares meet at each vertex to form a local configuration that itself tessellates the plane periodically. This structure arises from the affine Coxeter group , where the vertex figure captures the isogonal symmetry around each point. In three-dimensional Euclidean space, the cubic honeycomb {4,3,4} provides a contrasting example, with its vertex figure being the regular octahedron {3,4}, reflecting the arrangement of three squares around each edge and four such edges meeting at a vertex. This vertex figure, governed by the affine Coxeter group , emphasizes the periodic filling without gaps or overlaps in the ambient space.[27] Hyperbolic tilings extend these concepts to non-Euclidean geometries, where vertex figures manifest as hyperbolic polygons when the Schläfli parameters {p,q} satisfy . In such cases, the excess angle allows for more polygons around a vertex, resulting in curved vertex figures that embed within the hyperbolic plane; affine Coxeter groups no longer apply directly, giving way to hyperbolic Coxeter groups that generate these infinite, aperiodic-in-the-large configurations. For instance, the {7,3} tiling features a hyperbolic triangular vertex figure with angles determined by the geometry's negative curvature.[28] Paracompact honeycombs in hyperbolic three-space introduce further complexity, particularly those constructed via kaleidoscopic reflections analogous to the 24-cell's symmetry in higher dimensions, where vertices lie at infinity on horospheres. These structures, such as the square tiling honeycomb {4,3,}, possess vertex figures that are infinite Euclidean tilings, like the regular triangular tiling {3,6}, enabling unbounded cells while maintaining uniformity. Such honeycombs, classified under certain hyperbolic Coxeter groups with infinite branches in their diagrams, fill space with ideal polyhedra approaching asymptotic boundaries.[28]In higher-dimensional polytopes

In higher dimensions, the vertex figure of an n-dimensional polytope is itself an (n-1)-dimensional polytope that encodes the local arrangement of edges, faces, and higher cells meeting at a vertex, effectively reducing the dimensionality by one. For uniform polytopes, which are vertex-transitive with uniform facets, the vertex figure is likewise a uniform (n-1)-polytope, often described using generalized Wythoff symbols that specify the branching of mirrors in the symmetry group's Coxeter diagram. These symbols facilitate the enumeration of uniform polytopes in dimensions up to 6, a large number of which have been enumerated, though a complete list remains unfeasible.[29][30] Representative examples illustrate this dimensional reduction for regular 4-polytopes. The 4-simplex, or 5-cell, with Schläfli symbol {3,3,3}, has a vertex figure that is a regular tetrahedron {3,3}, reflecting the tetrahedral cells meeting four at each vertex. The 24-cell {3,4,3} has a cube {4,3} as its vertex figure, corresponding to the octahedral cells arranged cubically around each vertex. Similarly, the tesseract {4,3,3} features a regular tetrahedron {3,3} as vertex figure, arising from the cubic cells meeting tetrahedrally at each vertex. For infinite regular 4D honeycombs like the cubic honeycomb {4,3,3,4}, the vertex figure is the alternated cubic honeycomb {3,3,4}, a 3D tessellation of regular tetrahedra and octahedra.[31][32][33] In dimensions 5 and higher, vertex figures play a role in analyzing the combinatorial and geometric properties of polytopes relevant to theoretical physics, particularly reflexive polytopes used in string theory to construct Calabi-Yau manifolds for compactification. These structures, where vertices lie on lattice points and the origin is interior, rely on vertex figures to dissect local symmetries and dualities, aiding computations of Hodge numbers and mirror symmetry pairs essential for model-building in 10-dimensional string theories.[34][35]Related concepts

Edge figure

The edge figure of a polytope at a given edge is defined as the intersection of the polytope with an affine hyperplane parallel to the edge that separates the edge from the other vertices and another affine hyperplane orthogonal to the edge that separates its two endpoints, resulting in an -dimensional convex polytope for an -dimensional original polytope. This construction captures the local structure around the edge, analogous to how the vertex figure captures the structure around a vertex, and its face lattice is isomorphic to the link of the edge in the boundary complex of the polytope. More precisely, the edge figure can be viewed as the vertex figure of the link of , which consists of the facets incident to , forming a spherical -polytope when intersected with a small sphere centered at a point on the edge. In three dimensions, where an edge is incident to exactly two faces, the edge figure is a digon (or lune) on the unit sphere centered at the midpoint of the edge, bounded by the two great circles corresponding to the planes of the incident faces, with the angular measure of the lune equal to the dihedral angle between those faces. In higher dimensions, the edge figure generalizes to an -polytope reflecting the arrangement of multiple facets meeting at the edge. For a regular polytope with Schläfli symbol , the edge figure is a regular polytope given by the trailing symbols starting from the third entry, such as (a regular -gon) for a 4-polytope , where indicates the number of cells meeting at each edge. In three dimensions, this corresponds implicitly to , the digon, consistent with two faces meeting at each edge. The edge figure relates to other figures through iterative construction: specifically, the composition of the vertex figure and the edge figure reconstructs the face figure, as the face figure emerges from the edge figures within the vertex figure or vice versa in the symbolic derivation.Face figure

The face figure of a k-face in an -dimensional polytope is the -polytope formed from the link of in the face lattice of , excluding itself. This link consists of all faces of that are incident to but do not intersect its interior, capturing the local structure around . Geometrically, can be realized by intersecting with a supporting hyperplane near such that becomes a facet of the intersection, yielding a polytope of the appropriate dimension. In the case of polyhedra (, ), the face figure of a face is equivalent to the vertex figure of the dual polyhedron at the vertex corresponding to , which encodes the co-dihedral angles between and its adjacent faces. For example, in the regular icosahedron, the face figure of a triangular face is a triangle derived from the three adjacent triangular faces meeting along its edges. This construction extends recursively: for a -face with , select a vertex , compute the vertex figure , identify the corresponding -face in , and set . The dimension remains , and the empty face and full polytope serve as boundary cases with and . In abstract polytopes, the face figure at a rank- face is the section of the partially ordered set from that face to the maximal element, forming a ranked poset of rank where is the rank of the full polytope.Vertex normal figure

The vertex normal figure at a vertex of a polytope is constructed by taking the unit outward normals to the facets incident to that vertex and forming their convex hull on the unit sphere centered at the origin, resulting in a dual spherical polytope known as the spherical image of the vertex. This figure represents the intersection of the normal cone at the vertex with the unit sphere, where the normal cone is the conical hull generated by those unit normals. In three dimensions, for a polyhedral vertex where k facets meet, the vertex normal figure is a spherical (k-1)-gon whose vertices lie at the normal directions and whose edges are great circle arcs connecting normals of adjacent facets. The geometry of the vertex normal figure is intimately related to the polar reciprocal of the standard vertex figure. Specifically, the vertices of the normal figure correspond to the incident facets, and the lengths of its edges—which are the angular separations between adjacent unit normals—equal π minus the internal dihedral angle between the corresponding pair of facets, providing an inverse correspondence to the dihedral angles of the polyhedron. The interior angles of this spherical polytope, in turn, relate to the planar angles at the original vertex. For a regular polyhedron, the vertex normal figure coincides with the vertex figure of its dual polyhedron, reflecting the reciprocal symmetry inherent in Platonic solids. This construction is particularly useful in computational geometry for analyzing and generating offset surfaces of polytopes, where the normal cone at a vertex determines the spherical cap that appears in the parallel body at distance r from the original polyhedron, ensuring proper rounding at vertices without singularities. In mesh processing applications, such as those in 3D printing, vertex normal figures facilitate the creation of robust, watertight offset meshes for shelling models, preserving sharp features and avoiding self-intersections during additive manufacturing workflows. For instance, methods leverage these spherical polytopes to approximate normal cones for high-fidelity reconstructions in complex geometries.References

- https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/5-cell