Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hypercube

View on WikipediaIn geometry, a hypercube is an n-dimensional analogue of a square (n = 2) and a cube (n = 3); the special case for n = 4 is known as a tesseract. It is a closed, compact, convex figure whose 1-skeleton consists of groups of opposite parallel line segments aligned in each of the space's dimensions, perpendicular to each other and of the same length. A unit hypercube's longest diagonal in n dimensions is equal to .

An n-dimensional hypercube is more commonly referred to as an n-cube or sometimes as an n-dimensional cube.[1][2] The term measure polytope (originally from Elte, 1912)[3] is also used, notably in the work of H. S. M. Coxeter who also labels the hypercubes the γn polytopes.[4]

The hypercube is the special case of a hyperrectangle (also called an n-orthotope).

A unit hypercube is a hypercube whose side has length one unit. Often, the hypercube whose corners (or vertices) are the 2n points in Rn with each coordinate equal to 0 or 1 is called the unit hypercube.

Construction

[edit]By the number of dimensions

[edit]

A hypercube can be defined by increasing the numbers of dimensions of a shape:

- 0 – A point is a hypercube of dimension zero.

- 1 – If one moves this point one unit length, it will sweep out a line segment, which is a unit hypercube of dimension one.

- 2 – If one moves this line segment its length in a perpendicular direction from itself; it sweeps out a 2-dimensional square.

- 3 – If one moves the square one unit length in the direction perpendicular to the plane it lies on, it will generate a 3-dimensional cube.

- 4 – If one moves the cube one unit length into the fourth dimension, it generates a 4-dimensional unit hypercube (a unit tesseract).

This can be generalized to any number of dimensions. This process of sweeping out volumes can be formalized mathematically as a Minkowski sum: the d-dimensional hypercube is the Minkowski sum of d mutually perpendicular unit-length line segments, and is therefore an example of a zonotope.

The 1-skeleton of a hypercube is a hypercube graph.

Vertex coordinates

[edit]

A unit hypercube of dimension is the convex hull of all the points whose Cartesian coordinates are each equal to either or . These points are its vertices. The hypercube with these coordinates is also the cartesian product of copies of the unit interval . Another unit hypercube, centered at the origin of the ambient space, can be obtained from this one by a translation. It is the convex hull of the points whose vectors of Cartesian coordinates are

Here the symbol means that each coordinate is either equal to or to . This unit hypercube is also the cartesian product . Any unit hypercube has an edge length of and an -dimensional volume of .

The -dimensional hypercube obtained as the convex hull of the points with coordinates or, equivalently as the Cartesian product is also often considered due to the simpler form of its vertex coordinates. Its edge length is , and its -dimensional volume is .

Faces

[edit]Every hypercube admits, as its faces, hypercubes of a lower dimension contained in its boundary. A hypercube of dimension admits facets, or faces of dimension : a (-dimensional) line segment has endpoints; a (-dimensional) square has sides or edges; a -dimensional cube has square faces; a (-dimensional) tesseract has three-dimensional cubes as its facets. The number of vertices of a hypercube of dimension is (a usual, -dimensional cube has vertices, for instance).[5]

The number of the -dimensional hypercubes (just referred to as -cubes from here on) contained in the boundary of an -cube is

For example, the boundary of a -cube () contains cubes (-cubes), squares (-cubes), line segments (-cubes) and vertices (-cubes). This identity can be proven by a simple combinatorial argument: for each of the vertices of the hypercube, there are ways to choose a collection of edges incident to that vertex. Each of these collections defines one of the -dimensional faces incident to the considered vertex. Doing this for all the vertices of the hypercube, each of the -dimensional faces of the hypercube is counted times since it has that many vertices, and we need to divide by this number.

The number of facets of the hypercube can be used to compute the -dimensional volume of its boundary: that volume is times the volume of a -dimensional hypercube; that is, where is the length of the edges of the hypercube.

These numbers can also be generated by the linear recurrence relation.

- , with , and when , , or .

For example, extending a square via its 4 vertices adds one extra line segment (edge) per vertex. Adding the opposite square to form a cube provides line segments.

The extended f-vector for an n-cube can also be computed by expanding (concisely, (2,1)n), and reading off the coefficients of the resulting polynomial. For example, the elements of a tesseract is (2,1)4 = (4,4,1)2 = (16,32,24,8,1).

| m | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n-cube | Names | Schläfli Coxeter |

Vertex 0-face |

Edge 1-face |

Face 2-face |

Cell 3-face |

4-face |

5-face |

6-face |

7-face |

8-face |

9-face |

10-face |

| 0 | 0-cube | Point Monon |

( ) |

1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1-cube | Line segment Dion[7] |

{} |

2 | 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | 2-cube | Square Tetragon |

{4} |

4 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3-cube | Cube Hexahedron |

{4,3} |

8 | 12 | 6 | 1 | |||||||

| 4 | 4-cube | Tesseract Octachoron |

{4,3,3} |

16 | 32 | 24 | 8 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | 5-cube | Penteract Deca-5-tope |

{4,3,3,3} |

32 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| 6 | 6-cube | Hexeract Dodeca-6-tope |

{4,3,3,3,3} |

64 | 192 | 240 | 160 | 60 | 12 | 1 | ||||

| 7 | 7-cube | Hepteract Tetradeca-7-tope |

{4,3,3,3,3,3} |

128 | 448 | 672 | 560 | 280 | 84 | 14 | 1 | |||

| 8 | 8-cube | Octeract Hexadeca-8-tope |

{4,3,3,3,3,3,3} |

256 | 1024 | 1792 | 1792 | 1120 | 448 | 112 | 16 | 1 | ||

| 9 | 9-cube | Enneract Octadeca-9-tope |

{4,3,3,3,3,3,3,3} |

512 | 2304 | 4608 | 5376 | 4032 | 2016 | 672 | 144 | 18 | 1 | |

| 10 | 10-cube | Dekeract Icosa-10-tope |

{4,3,3,3,3,3,3,3,3} |

1024 | 5120 | 11520 | 15360 | 13440 | 8064 | 3360 | 960 | 180 | 20 | 1 |

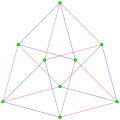

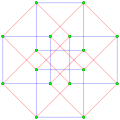

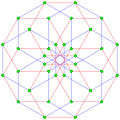

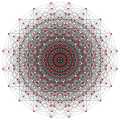

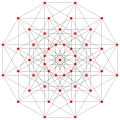

Graphs

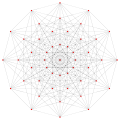

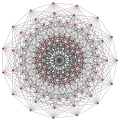

[edit]An n-cube can be projected inside a regular 2n-gonal polygon by a skew orthogonal projection, shown here from the line segment to the 15-cube.

Line segment |

Square |

Cube |

Tesseract |

5-cube |

6-cube |

7-cube |

8-cube |

9-cube |

10-cube |

11-cube |

12-cube |

13-cube |

14-cube |

15-cube |

Related families of polytopes

[edit]The hypercubes are one of the few families of regular polytopes that are represented in any number of dimensions.[8]

The hypercube family is one of three regular polytope families, labeled by Coxeter as γn. The other two are the hypercube dual family, the cross-polytopes, labeled as βn, and the simplices, labeled as αn. A fourth family, the infinite tessellations of hypercubes, is labeled as δn.

Another related family of semiregular and uniform polytopes is the demihypercubes, which are constructed from hypercubes with alternate vertices deleted and simplex facets added in the gaps, labeled as hγn.

n-cubes can be combined with their duals (the cross-polytopes) to form compound polytopes:

- In two dimensions, we obtain the octagrammic star figure {8/2},

- In three dimensions we obtain the compound of cube and octahedron,

- In four dimensions we obtain the compound of tesseract and 16-cell.

Relation to (n−1)-simplices

[edit]The graph of the n-hypercube's edges is isomorphic to the Hasse diagram of the (n−1)-simplex's face lattice. This can be seen by orienting the n-hypercube so that two opposite vertices lie vertically, corresponding to the (n−1)-simplex itself and the null polytope, respectively. Each vertex connected to the top vertex then uniquely maps to one of the (n−1)-simplex's facets (n−2 faces), and each vertex connected to those vertices maps to one of the simplex's n−3 faces, and so forth, and the vertices connected to the bottom vertex map to the simplex's vertices.

This relation may be used to generate the face lattice of an (n−1)-simplex efficiently, since face lattice enumeration algorithms applicable to general polytopes are more computationally expensive.

Generalized hypercubes

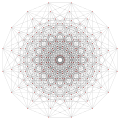

[edit]Regular complex polytopes can be defined in complex Hilbert space called generalized hypercubes, γp

n = p{4}2{3}...2{3}2, or ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ..

..![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() . Real solutions exist with p = 2, i.e. γ2

. Real solutions exist with p = 2, i.e. γ2

n = γn = 2{4}2{3}...2{3}2 = {4,3,..,3}. For p > 2, they exist in . The facets are generalized (n−1)-cube and the vertex figure are regular simplexes.

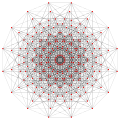

The regular polygon perimeter seen in these orthogonal projections is called a Petrie polygon. The generalized squares (n = 2) are shown with edges outlined as red and blue alternating color p-edges, while the higher n-cubes are drawn with black outlined p-edges.

The number of m-face elements in a p-generalized n-cube are: . This is pn vertices and pn facets.[9]

| p=2 | p=3 | p=4 | p=5 | p=6 | p=7 | p=8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

γ2 2 = {4} = 4 vertices |

γ3 2 = 9 vertices |

γ4 2 = 16 vertices |

γ5 2 = 25 vertices |

γ6 2 = 36 vertices |

γ7 2 = 49 vertices |

γ8 2 = 64 vertices | ||

γ2 3 = {4,3} = 8 vertices |

γ3 3 = 27 vertices |

γ4 3 = 64 vertices |

γ5 3 = 125 vertices |

γ6 3 = 216 vertices |

γ7 3 = 343 vertices |

γ8 3 = 512 vertices | ||

γ2 4 = {4,3,3} = 16 vertices |

γ3 4 = 81 vertices |

γ4 4 = 256 vertices |

γ5 4 = 625 vertices |

γ6 4 = 1296 vertices |

γ7 4 = 2401 vertices |

γ8 4 = 4096 vertices | ||

γ2 5 = {4,3,3,3} = 32 vertices |

γ3 5 = 243 vertices |

γ4 5 = 1024 vertices |

γ5 5 = 3125 vertices |

γ6 5 = 7776 vertices |

γ7 5 = 16,807 vertices |

γ8 5 = 32,768 vertices | ||

γ2 6 = {4,3,3,3,3} = 64 vertices |

γ3 6 = 729 vertices |

γ4 6 = 4096 vertices |

γ5 6 = 15,625 vertices |

γ6 6 = 46,656 vertices |

γ7 6 = 117,649 vertices |

γ8 6 = 262,144 vertices | ||

γ2 7 = {4,3,3,3,3,3} = 128 vertices |

γ3 7 = 2187 vertices |

γ4 7 = 16,384 vertices |

γ5 7 = 78,125 vertices |

γ6 7 = 279,936 vertices |

γ7 7 = 823,543 vertices |

γ8 7 = 2,097,152 vertices | ||

γ2 8 = {4,3,3,3,3,3,3} = 256 vertices |

γ3 8 = 6561 vertices |

γ4 8 = 65,536 vertices |

γ5 8 = 390,625 vertices |

γ6 8 = 1,679,616 vertices |

γ7 8 = 5,764,801 vertices |

γ8 8 = 16,777,216 vertices |

Relation to exponentiation

[edit]Any positive integer raised to another positive integer power will yield a third integer, with this third integer being a specific type of figurate number corresponding to an n-cube with a number of dimensions corresponding to the exponential. For example, the exponent 2 will yield a square number or "perfect square", which can be arranged into a square shape with a side length corresponding to that of the base. Similarly, the exponent 3 will yield a perfect cube, an integer which can be arranged into a cube shape with a side length of the base. As a result, the act of raising a number to 2 or 3 is more commonly referred to as "squaring" and "cubing", respectively. However, the names of higher-order hypercubes do not appear to be in common use for higher powers.

See also

[edit]- Hypercube interconnection network of computer architecture

- Hyperoctahedral group, the symmetry group of the hypercube

- Hypersphere

- Simplex

- Parallelotope

- Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), a painting by Salvador Dalí featuring an unfolded 4-cube

Notes

[edit]- ^ Paul Dooren; Luc Ridder (1976). "An adaptive algorithm for numerical integration over an n-dimensional cube". Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics. 2 (3): 207–217. doi:10.1016/0771-050X(76)90005-X.

- ^ Xiaofan Yang; Yuan Tang (15 April 2007). "A (4n − 9)/3 diagnosis algorithm on n-dimensional cube network". Information Sciences. 177 (8): 1771–1781. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2006.10.002.

- ^ Elte, E. L. (1912). "IV, Five dimensional semiregular polytope". The Semiregular Polytopes of the Hyperspaces. Netherlands: University of Groningen. ISBN 141817968X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Coxeter 1973, pp. 122–123, §7.2 see illustration Fig 7.2C.

- ^ Miroslav Vořechovský; Jan Mašek; Jan Eliáš (November 2019). "Distance-based optimal sampling in a hypercube: Analogies to N-body systems". Advances in Engineering Software. 137 102709. doi:10.1016/j.advengsoft.2019.102709. ISSN 0965-9978.

- ^ Coxeter 1973, p. 122, §7·25.

- ^ Johnson, Norman W.; Geometries and Transformations, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p.224.

- ^ Noga Alon (1992). "Transmitting in the n-dimensional cube". Discrete Applied Mathematics. 37–38: 9–11. doi:10.1016/0166-218X(92)90121-P.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1974), Regular complex polytopes, London & New York: Cambridge University Press, p. 180, MR 0370328.

References

[edit]- Bowen, J. P. (April 1982). "Hypercube". Practical Computing. 5 (4): 97–99. Archived from the original on 2008-06-30. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973). "§7.2. see illustration Fig. 7-2c". Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). Dover. pp. 122-123. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. p. 296, Table I (iii): Regular Polytopes, three regular polytopes in n dimensions (n ≥ 5)

- Hill, Frederick J.; Gerald R. Peterson (1974). Introduction to Switching Theory and Logical Design: Second Edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-39882-9. Cf Chapter 7.1 "Cubical Representation of Boolean Functions" wherein the notion of "hypercube" is introduced as a means of demonstrating a distance-1 code (Gray code) as the vertices of a hypercube, and then the hypercube with its vertices so labelled is squashed into two dimensions to form either a Veitch diagram or Karnaugh map.

External links

[edit]- Weisstein, Eric W. "Hypercube". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Hypercube graphs". MathWorld.

- Rotating a Hypercube by Enrique Zeleny, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Rudy Rucker and Farideh Dormishian's Hypercube Downloads

- A001787 Number of edges in an n-dimensional hypercube. at OEIS

Hypercube

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A hypercube, also known as an n-cube, is the n-dimensional analog of a square in two dimensions and a cube in three dimensions. It is a convex polytope embedded in n-dimensional Euclidean space , formed as the convex hull of its vertices, which are all points with coordinates in the set .[2] This structure generalizes the familiar lower-dimensional cases, such as the square as the 2-cube.[2] The edges of a hypercube connect pairs of vertices that differ in exactly one coordinate, corresponding to a Hamming distance of 1 between their binary representations.[2] In graph theory, the hypercube is often denoted as , where the vertices represent binary strings of length n, and edges represent single-bit flips.[5] To understand the hypercube, prerequisite concepts include polytopes, dimensions, and convexity. A polytope is a bounded geometric figure in n-dimensional space defined by the intersection of half-spaces, generalizing polygons and polyhedra to higher dimensions.[6] The dimension n refers to the number of independent coordinates needed to specify points in the ambient space . Convexity ensures that the line segment joining any two points within the hypercube lies entirely within it, making it a convex set.Low-Dimensional Examples

The concept of a hypercube begins with its lowest-dimensional manifestations, providing intuition for higher dimensions. The 0-cube, or zeroth-dimensional hypercube, is simply a single point with no extent in any direction, possessing 1 vertex and no edges or faces.[2] Progressing to the 1-cube, this takes the form of a line segment connecting two vertices at its endpoints, featuring 2 vertices and 1 edge, with no faces.[2] In two dimensions, the 2-cube appears as a square, which has 4 vertices, 4 edges, and 1 square face consisting of the square itself.[2] The familiar 3-cube, or cube, extends this to three dimensions with 8 vertices, 12 edges, 6 square faces, and 1 cubic cell that encloses the volume.[2] Each of these builds upon the previous by introducing a new perpendicular direction, effectively duplicating the lower-dimensional figure and connecting corresponding elements with edges or higher facets.[2] The 4-cube, known as the tesseract, further generalizes this pattern in four dimensions, comprising 16 vertices, 32 edges, 24 square faces, 8 cubic cells, and 1 tesseractic cell.[4] To visualize the tesseract in three-dimensional space, projections such as the Schlegel diagram are employed, where one cubic cell is represented as an outer cube, and the remaining seven cells are projected inward as smaller cubes connected by edges, preserving the topological structure.[4] This progression illustrates how each additional dimension duplicates the (n-1)-cube and links the copies along the new axis, fostering an intuitive grasp of hypercubic geometry.[2]Construction

Coordinate Representation

The vertices of an n-dimensional hypercube are represented as the set of all points in with coordinates , where each .[2] This binary coordinate system embeds the hypercube directly in Euclidean space, with adjacent vertices connected by edges when their coordinate vectors differ in exactly one position.[2] The standard edge length in this representation is 1, as the Euclidean distance between adjacent vertices and satisfies .[2] For low dimensions, the vertex coordinates are as follows:- For : , .

- For : , , , .

- For : , , , , , , , .[2]

Recursive Construction

The recursive construction of an n-dimensional hypercube, denoted , builds upon lower-dimensional hypercubes by starting with two disjoint copies of the (n-1)-dimensional hypercube and connecting corresponding vertices between them with edges along the new dimension.[8] This method defines recursively as the Cartesian product , where is the complete graph on two vertices (a line segment), for , with the base case being a single vertex.[9] Geometrically, this corresponds to extruding the along a direction perpendicular to its embedding in (n-1)-dimensional space, creating parallel "slices" connected by the new edges.[8] The vertex set of is formed as the union , where the two factors represent the two copies of distinguished by the new coordinate.[9] The edges of consist of the edges within each slice (identical to those of ) and the new edges connecting vertices that differ only in the nth coordinate (i.e., pairs and for each ).[8] This construction admits an inductive proof that is indeed an n-dimensional hypercube with the expected combinatorial structure. The base case for is the line segment , which has 2 vertices and 1 edge.[9] Assuming has vertices and edges, the inductive step adds new vertices (from the second copy) and new edges (the connections between copies), yielding and total edges, matching the defining properties of the n-hypercube.[8] For visualization, applying this recursion to produces the tesseract from two disjoint 3-cubes (ordinary cubes), where each vertex of one cube connects to its counterpart in the other via edges in the fourth dimension, forming the 8 cubic cells of the tesseract.[8]Structural Elements

Vertices, Edges, and Faces

The faces of an n-dimensional hypercube, also known as an n-cube, consist of all its k-dimensional sub-hypercubes for , where a k-face is itself a k-cube embedded in the n-cube. The total number of k-faces is given by the formula , which arises combinatorially from selecting the k dimensions that vary freely between 0 and 1, while fixing each of the remaining n-k dimensions to either 0 or 1.[2][3] For k=0, this yields vertices; for k=1, edges; and for k=n, a single n-dimensional cell comprising the entire hypercube itself.[2] Each k-face can be explicitly constructed by choosing a subset of k coordinates from the n-dimensional space to vary over [0,1], with the orthogonal n-k coordinates held constant at specific binary values (0 or 1), thereby determining its position within the hypercube.[3] This coordinate-based representation highlights the hypercube's regularity, as reflected in its Schläfli symbol for , which encodes the fact that it is a regular polytope with square 2-faces and successive vertex figures that are (n-2)-simplices for n ≥ 3.[2] In terms of incidence relations within the face lattice, each k-face is contained in exactly (n - k) distinct (k+1)-faces, obtained by selecting one of the n-k fixed coordinates and allowing it to vary while keeping the others fixed.[3] Conversely, each (k+1)-face contains k-faces as its boundary elements, following the general face-counting formula applied to a standalone (k+1)-cube; for instance, the 3-dimensional cube (a single cell of the 3-cube) is bounded by 6 square (2-dimensional) faces.[2]| Dimension n | Vertices (k=0) | Edges (k=1) | 2-Faces | ... | (n-1)-Faces | n-Cell (k=n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (square) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 3 (cube) | 8 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 1 | |

| 4 (tesseract) | 16 | 32 | 24 | 8 | 8 | 1 |

![{\displaystyle [0,1]^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/40160923273b7109968df994dca832b91d957bf2)

![{\displaystyle [0,1]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)

![{\displaystyle [-1/2,1/2]^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/98cea6b9a196dae533439e1146656e8c29dd732d)

![{\displaystyle [-1,1]^{n}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6a008254b1bf6d63ac3b13548c4c31180bcd43de)