Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Air navigation

View on WikipediaThe basic principles of air navigation are similar to those of general navigation, involving the planning, recording, and controlling of a craft’s movement from one location to another.[1] In aviation, navigation plays a critical role in ensuring that aircraft operate safely and efficiently within controlled airspace and along designated routes, in accordance with international standards.[2]

Successful air navigation involves piloting an aircraft from place to place without getting lost, not breaking the laws applying to aircraft, or endangering the safety of those on board or on the ground. Air navigation differs from the navigation of surface craft in several ways; aircraft travel at relatively high speeds, leaving less time to calculate their position en route. Aircraft normally cannot stop in mid-air to ascertain their position at leisure. Aircraft are safety-limited by the amount of fuel they can carry; a surface vehicle can usually get lost, run out of fuel, then simply await rescue. There is no in-flight rescue for most aircraft. Additionally, collisions with obstructions are usually fatal. Therefore, constant awareness of position is critical for aircraft pilots.

The techniques used for navigation in the air will depend on whether the aircraft is flying under visual flight rules (VFR) or instrument flight rules (IFR). In the latter case, the pilot will navigate exclusively using instruments and radio navigation aids such as beacons, or as directed under radar control by air traffic control. In the former case, a pilot will largely navigate using "dead reckoning" combined with visual observations (known as pilotage), with reference to appropriate maps. This may be supplemented using radio navigation aids or satellite based positioning systems.

Route planning

[edit]

The first step in navigation is deciding where one wishes to go. A private pilot planning a flight under VFR will usually use an aeronautical chart of the area which is published specifically for the use of pilots. This map will depict controlled airspace, radio navigation aids and airfields prominently, as well as hazards to flying such as mountains, tall radio masts, etc. It also includes sufficient ground detail – towns, roads, wooded areas – to aid visual navigation. In the UK, the CAA publishes a series of maps covering the whole of the UK at various scales, updated annually. The information is also updated in the notices to airmen, or NOTAMs.

The pilot will choose a route, taking care to avoid controlled airspace that is not permitted for the flight, restricted areas, danger areas and so on. The chosen route is plotted on the map, and the lines drawn are called the track. The aim of all subsequent navigation is to follow the chosen track as accurately as possible. Occasionally, the pilot may elect on one leg to follow a clearly visible feature on the ground such as a railway track, river, highway, or coast.

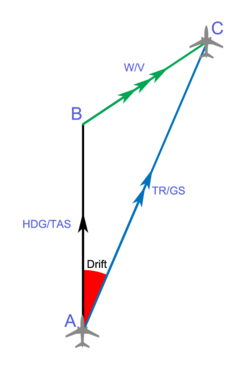

When an aircraft is in flight, it is moving relative to the body of air through which it is flying; therefore maintaining an accurate ground track is not as easy as it might appear, unless there is no wind at all—a very rare occurrence. The pilot must adjust heading to compensate for the wind, in order to follow the ground track. Initially the pilot will calculate headings to fly for each leg of the trip prior to departure, using the forecast wind directions and speeds supplied by the meteorological authorities for the purpose. These figures are generally accurate and updated several times per day, but the unpredictable nature of the weather means that the pilot must be prepared to make further adjustments in flight. A general aviation (GA) pilot will often make use of either a flight computer – a type of slide rule – or a purpose-designed electronic navigational computer to calculate initial headings.

The primary instrument of navigation is the magnetic compass. The needle or card aligns itself to magnetic north, which does not coincide with true north, so the pilot must also allow for this, called the magnetic variation (or declination). The variation that applies locally is also shown on the flight map. Once the pilot has calculated the actual headings required, the next step is to calculate the flight times for each leg. This is necessary to perform accurate dead reckoning. The pilot also needs to take into account the slower initial airspeed during climb to calculate the time to top of climb. It is also helpful to calculate the top of descent, or the point at which the pilot would plan to commence the descent for landing.

The flight time will depend on both the desired cruising speed of the aircraft, and the wind – a tailwind will shorten flight times, a headwind will increase them. The flight computer has scales to help pilots compute these easily.

The point of no return, sometimes referred to as the PNR, is the point on a flight at which a plane has just enough fuel, plus any mandatory reserve, to return to the airfield from which it departed. Beyond this point that option is closed, and the plane must proceed to some other destination. Alternatively, with respect to a large region without airfields, e.g. an ocean, it can mean the point before which it is closer to turn around and after which it is closer to continue. Similarly, the Equal time point, referred to as the ETP (also critical point), is the point in the flight where it would take the same time to continue flying straight, or track back to the departure aerodrome. The ETP is not dependent on fuel, but wind, giving a change in ground speed out from, and back to the departure aerodrome. In Nil wind conditions, the ETP is located halfway between the two aerodromes, but in reality it is shifted depending on the windspeed and direction.

The aircraft that is flying across the Ocean for example, would be required to calculate ETPs for one engine inoperative, depressurization, and a normal ETP; all of which could actually be different points along the route. For example, in one engine inoperative and depressurization situations the aircraft would be forced to lower operational altitudes, which would affect its fuel consumption, cruise speed and ground speed. Each situation therefore would have a different ETP.

Commercial aircraft are not allowed to operate along a route that is out of range of a suitable place to land if an emergency such as an engine failure occurs. The ETP calculations serve as a planning strategy, so flight crews always have an 'out' in an emergency event, allowing a safe diversion to their chosen alternate.

The final stage is to note which areas the route will pass through or over, and to make a note of all of the things to be done – which ATC units to contact, the appropriate frequencies, visual reporting points, and so on. It is also important to note which pressure setting regions will be entered, so that the pilot can ask for the QNH (air pressure) of those regions. Finally, the pilot should have in mind some alternative plans in case the route cannot be flown for some reason – unexpected weather conditions being the most common. At times the pilot may be required to file a flight plan for an alternate destination and to carry adequate fuel for this. The more work a pilot can do on the ground prior to departure, the easier it will be in the air.

IFR planning

[edit]Instrument flight rules (IFR) navigation is similar to visual flight rules (VFR) flight planning except that the task is generally made simpler by the use of special charts that show IFR routes from beacon to beacon with the lowest safe altitude (LSALT), bearings (in both directions), and distance marked for each route. IFR pilots may fly on other routes but they then must perform all such calculations themselves; the LSALT calculation is the most difficult. The pilot then needs to look at the weather and minimum specifications for landing at the destination airport and the alternate requirements. Pilots must also comply with all the rules including their legal ability to use a particular instrument approach depending on how recently they last performed one.

In recent years, strict beacon-to-beacon flight paths have started to be replaced by routes derived through performance-based navigation (PBN) techniques. When operators develop flight plans for their aircraft, the PBN approach encourages them to assess the overall accuracy, integrity, availability, continuity, and functionality of the aggregate navigation aids present within the applicable airspace. Once these determinations have been made, the operator develops a route that is the most time and fuel efficient while respecting all applicable safety concerns—thereby maximizing both the aircraft's and the airspace's overall performance capabilities.

Under the PBN approach, technologies evolve over time (e.g., ground beacons become satellite beacons) without requiring the underlying aircraft operation to be recalculated. Also, navigation specifications used to assess the sensors and equipment that are available in an airspace can be cataloged and shared to inform equipment upgrade decisions and the ongoing harmonization of the world's various air navigation systems.

In flight

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2021) |

Once in flight, the pilot must take pains to stick to plan, otherwise getting lost is all too easy. This is especially true if flying in the dark or over featureless terrain. This means that the pilot must stick to the calculated headings, heights and speeds as accurately as possible, unless flying under visual flight rules. The visual pilot must regularly compare the ground with the map, (pilotage) to ensure that the track is being followed although adjustments are generally calculated and planned. Usually, the pilot will fly for some time as planned to a point where features on the ground are easily recognised. If the wind is different from that expected, the pilot must adjust heading accordingly, but this is not done by guesswork, but by mental calculation – often using the 1 in 60 rule. For example, a two degree error at the halfway stage can be corrected by adjusting heading by four degrees the other way to arrive in position at the end of the leg. This is also a point to reassess the estimated time for the leg. A good pilot will become adept at applying a variety of techniques to stay on track.

While the compass is the primary instrument used to determine one's heading, pilots will usually refer instead to the direction indicator (DI), a gyroscopically driven device which is much more stable than a compass. The compass reading will be used to correct for any drift (precession) of the DI periodically. The compass itself will only show a steady reading when the aircraft has been in straight and level flight long enough to allow it to settle.

Should the pilot be unable to complete a leg – for example bad weather arises, or the visibility falls below the minima permitted by the pilot's license, the pilot must divert to another route. Since this is an unplanned leg, the pilot must be able to mentally calculate suitable headings to give the desired new track. Using the flight computer in flight is usually impractical, so mental techniques to give rough and ready results are used. The wind is usually allowed for by assuming that sine A = A, for angles less than 60° (when expressed in terms of a fraction of 60° – e.g. 30° is 1/2 of 60°, and sine 30° = 0.5), which is adequately accurate. A method for computing this mentally is the clock code. However the pilot must be extra vigilant when flying diversions to maintain awareness of position.

Some diversions can be temporary – for example to skirt around a local storm cloud. In such cases, the pilot can turn 60 degrees away his desired heading for a given period of time. Once clear of the storm, he can then turn back in the opposite direction 120 degrees, and fly this heading for the same length of time. This is a 'wind-star' maneuver and, with no winds aloft, will place him back on his original track with his trip time increased by the length of one diversion leg.

Another reason for not relying on the magnetic compass during flight, apart from calibrating the Heading indicator from time to time, is because magnetic compasses are subject to errors caused by flight conditions and other internal and external interferences on the magnet system.[3]

Navigation aids

[edit]

Many GA aircraft are fitted with a variety of navigation aids, such as Automatic direction finder (ADF), inertial navigation, compasses, radar navigation, VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) and Global navigation satellite system (GNSS).

ADF uses non-directional beacons (NDBs) on the ground to drive a display which shows the direction of the beacon from the aircraft. The pilot may use this bearing to draw a line on the map to show the bearing from the beacon. By using a second beacon, two lines may be drawn to locate the aircraft at the intersection of the lines. This is called a cross-cut. Alternatively, if the track takes the flight directly overhead a beacon, the pilot can use the ADF instrument to maintain heading relative to the beacon, though "following the needle" is bad practice, especially in the presence of a strong cross wind – the pilot's actual track will spiral in towards the beacon, not what was intended. NDBs also can give erroneous readings because they use very long wavelengths, which are easily bent and reflected by ground features and the atmosphere. NDBs continue to be used as a common form of navigation in some countries with relatively few navigational aids.

VOR is a more sophisticated system, and is still the primary air navigation system established for aircraft flying under IFR in those countries with many navigational aids. In this system, a beacon emits a specially modulated signal which consists of two sine waves which are out of phase. The phase difference corresponds to the actual bearing relative to magnetic north (in some cases true north) that the receiver is from the station. The upshot is that the receiver can determine with certainty the exact bearing from the station. Again, a cross-cut is used to pinpoint the location. Many VOR stations also have additional equipment called DME (distance measuring equipment) which will allow a suitable receiver to determine the exact distance from the station. Together with the bearing, this allows an exact position to be determined from a single beacon alone. For convenience, some VOR stations also transmit local weather information which the pilot can listen in to, perhaps generated by an Automated Surface Observing System. A VOR which is co-located with a DME is usually a component of a TACAN.

Prior to the advent of GNSS, Celestial Navigation was also used by trained navigators.[4] This was especially true on military bombers and transport aircraft in the event of all electronic navigational aids being turned off in time of war. Originally navigators used an astrodome and regular sextant or bubble octant but the more streamlined periscopic sextant was used from the 1940s to the 1990s. From the 1970s airliners used inertial navigation systems, especially on inter-continental routes, until the shooting down of Korean Air Lines Flight 007 in 1983 prompted the US government to make GPS available for civilian use.

Finally, an aircraft may be supervised from the ground using surveillance information from e.g. radar or multilateration. ATC can then feed back information to the pilot to help establish position, or can actually tell the pilot the position of the aircraft, depending on the level of ATC service the pilot is receiving.

The use of GNSS in aircraft is becoming increasingly common. GNSS provides very precise aircraft position, altitude, heading and ground speed information. GNSS makes navigation precision once reserved to large RNAV-equipped aircraft available to the GA pilot. Recently, many airports include GNSS instrument approaches. GNSS approaches consist of either overlays to existing precision and non-precision approaches or stand-alone GNSS approaches. Approaches having the lowest decision heights generally require that GNSS be augmented by a second system—e.g., the FAA's Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS).

Flight navigator

[edit]Civilian flight navigators (a mostly redundant aircrew position, also called 'air navigator' or 'flight navigator'), were employed on older aircraft, typically between the late-1910s and the 1970s. The crew member, occasionally two navigation crew members for some flights, was responsible for the trip navigation, including its dead reckoning and celestial navigation. This was especially essential when trips were flown over oceans or other large bodies of water, where radio navigation aids were not originally available. (Satellite coverage is now provided worldwide). As sophisticated electronic and GNSS systems came online, the navigator's position was discontinued and its function was assumed by dual-licensed pilot-navigators, and still later by the flight's primary pilots (Captain and First Officer), resulting in a downsizing in the number of aircrew positions for commercial flights. As the installation of electronic navigation systems into the Captain's and FO's instrument panels was relatively straight forward, the navigator's position in commercial aviation (but not necessarily military aviation) became redundant. (Some countries task their air forces to fly without navigation aids during wartime, thus still requiring a navigator's position). Most civilian air navigators were retired or made redundant by the early 1980s.[5]

See also

[edit]- Aeronautical chart

- Air navigation service provider

- Air traffic control

- Air traffic obstacle

- Aircraft

- Aircrew

- Automatic dependent surveillance – broadcast

- Aviation safety

- Drift meter

- ETOPS

- Flight computer

- Flight instruments

- Flight management system

- Great-circle distance

- Guidance, navigation and control

- Instrument landing system

- Radio navigation

- Receiver autonomous integrity monitoring

- Spherical trigonometry

- Transatlantic flight

- Wind triangle

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Bowditch, Nathaniel (1995). "Glossary". The American Practical Navigator (PDF). Vol. 9. Bethesda, Maryland: National Imagery and Mapping Agency. p. 815. ISBN 978-0-939837-54-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-20. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- ^ "Annex 1 — Personnel Licensing". International Civil Aviation Organization. Retrieved 20 August 2025.

- ^ Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge, 2016, U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Aviation Administration, pp. 8-24, 8-25, 8-26, 8-27

- ^ Wolper, James S. (2001-06-13). Understanding Mathematics for Aircraft Navigation. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 109-150. ISBN 978-0-07-163879-1.

- ^ Grierson, Mike. Aviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator, FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

Bibliography

- Grierson, Mike. Aviation History–Demise of the Flight Navigator, FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

- FAA Handbook FAA-H-8083-18: Flight Navigator Handbook; 2011; retrieved October 7, 2017; https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/media/FAA-H-8083-18.pdf.

- Richards, Stu. Remember The Airline Navigator, Props, Pistons, Old Jets And the Good Ole Days of Flying website, January 7, 2009. Retrieved August 31, 2014.