Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

| Greater wing of sphenoid bone | |

|---|---|

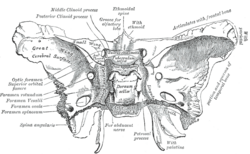

Figure 1: Sphenoid bone, upper surface. | |

Figure 2: Sphenoid bone, anterior and inferior surfaces. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ala major ossis sphenoidalis |

| TA98 | A02.1.05.024 |

| TA2 | 610 |

| FMA | 52868 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone, or alisphenoid, is a bony process of the sphenoid bone, positioned in the skull behind each eye. There is one on each side, extending from the side of the body of the sphenoid and curving upward, laterally, and backward.

Structure

[edit]The greater wings of the sphenoid are two strong processes of bone, which arise from the sides of the body, and are curved upward, laterally, and backward; the posterior part of each projects as a triangular process that fits into the angle between the squamous and the petrous part of the temporal bone and presents at its apex a downward-directed process, the spine of sphenoid bone.

Cerebral surface

[edit]The superior or cerebral surface of each greater wing [Fig. 1] forms part of the middle cranial fossa; it is deeply concave, and presents depressions for the convolutions of the temporal lobe of the brain. It has a number of foramina (holes) in it:

- The foramen rotundum is a circular aperture at its anterior and medial part; it transmits the maxillary nerve.

- The foramen ovale is behind and lateral to this; it transmits the mandibular nerve, the accessory meningeal artery, and sometimes the lesser petrosal nerve.

- The sphenoidal emissary foramen is occasionally present; it is a small aperture medial to the foramen ovale, opposite the root of the pterygoid process; it opens below near the scaphoid fossa, and transmits a small vein from the cavernous sinus.

- The foramen spinosum, in the posterior angle near to and in front of the spine; it is a short canal that transmits the middle meningeal vessels and a recurrent branch from the mandibular nerve.

- The foramen petrosum, a small occasional opening, between the foramen spinosum and foramen ovale, for transmission of the lesser petrosal nerve.

Lateral surface

[edit]The lateral surface [Fig. 2] is convex, and divided by a transverse ridge, the infratemporal crest, into two portions.

- The superior temporal surface, convex from above downward, concave from before backward, forms a part of the temporal fossa, and gives attachment to the temporalis;

- the inferior infratemporal surface, smaller in size and concave, enters into the formation of the infratemporal fossa, and, together with the infratemporal crest, serves as an attachment to the lateral pterygoid muscle.

It is pierced by the foramen ovale and foramen spinosum, and at its posterior part is the sphenoidal spine, which is frequently grooved on its medial surface for the chorda tympani nerve.

To the sphenoidal spine are attached the sphenomandibular ligament and the tensor veli palatini muscle.

Medial to the anterior extremity of the infratemporal crest is a triangular process that serves to increase the attachment of the lateral pterygoid muscle; extending downward and medialward from this process on to the front part of the lateral pterygoid plate is a ridge that forms the anterior limit of the infratemporal surface, and, in the articulated skull, the posterior boundary of the pterygomaxillary fissure.

Orbital surface

[edit]The orbital surface of the great wing [Fig. 2], smooth, and quadrilateral in shape, is directed forward and medially and forms the posterior part of the lateral wall of the orbit.

- Its upper serrated edge articulates with the orbital plate of the frontal bone.

- Its inferior rounded border forms the postero-lateral boundary of the inferior orbital fissure.

- Its medial sharp margin forms the lower boundary of the superior orbital fissure and has projecting from about its center a little tubercle that gives attachment to the inferior head of the lateral rectus muscle; at the upper part of this margin is a notch for the transmission of a recurrent branch of the lacrimal artery.

- Its lateral margin is serrated and articulates with the zygomatic bone.

- Below the medial end of the superior orbital fissure is a grooved surface, which forms the posterior wall of the pterygopalatine fossa, and is pierced by the foramen rotundum.

Margin

[edit]Commencing from behind [Fig. 2], that portion of the circumference of the great wing that extends from the body to the spine is irregular.

- Its medial half forms the anterior boundary of the foramen lacerum, and presents the posterior aperture of the pterygoid canal for the passage of the corresponding nerve and artery.

- Its lateral half articulates, by means of a synchondrosis, with the petrous portion of the temporal, and between the two bones on the under surface of the skull, is a furrow, the sulcus of the auditory tube, for the lodgement of the cartilaginous part of the auditory tube.

In front of the spine the circumference presents a concave, serrated edge, bevelled at the expense of the inner table below, and of the outer table above, for articulation with the squamous part of the temporal bone.

At the tip of the great wing is a triangular portion, bevelled at the expense of the internal surface, for articulation with the sphenoidal angle of the parietal bone; this region is named the pterion.

Medial to this is a triangular, serrated surface, for articulation with the frontal bone; this surface is continuous medially with the sharp edge that forms the lower boundary of the superior orbital fissure, and laterally with the serrated margin for articulation with the zygomatic bone.

Development

[edit]The greater wing of the sphenoid bone starts as a separate bone, and is still separate at birth in humans.

Function

[edit]The sphenoid bone assists with the formation of the base and the sides of the skull, and the floors and walls of the orbits. It is the site of attachment for most of the muscles of mastication. Many foramina and fissures are located in the sphenoid that carry nerves and blood vessels of the head and neck, such as the superior orbital fissure (with ophthalmic nerve), foramen rotundum (with maxillary nerve) and foramen ovale (with mandibular nerve).[1]

Clinical significance

[edit]In patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, malformation of the sphenoid bone wings may occur, due to aberrant cell development. This can ultimately lead to blindness if left untreated.

In other animals

[edit]In many mammals, e.g. the dog, the greater wing of the sphenoid bone stays through life a separate bone called the alisphenoid.

Additional images

[edit]-

The seven bones that articulate to form the orbit.

-

Base of skull. Inferior surface.

-

Left infratemporal fossa.

-

The skull from the front.

-

Articulation of the mandible. Medial aspect.

-

Muscles of the right orbit.

-

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

-

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

-

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

-

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

-

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

External links

[edit]- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.

- "Anatomy diagram: 34257.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22.

References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 149 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 149 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Fehrenbach; Herring (2012). Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck. Elsevier. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4377-2419-6.

Greater wing of sphenoid bone

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Location and relations

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone is a triangular, plate-like projection that arises posterolaterally from the body of the sphenoid bone and extends laterally, superiorly, and posteriorly in a curved manner, resembling a bat wing.[3][4][5] It forms key components of the skull's architecture, including the floor of the middle cranial fossa, the posterolateral wall of the orbit, and the lateral wall of the infratemporal fossa (also contributing to the temporal fossa).[3][1][4] In terms of spatial relations, the greater wing articulates anteriorly with the frontal bone and laterally with the zygomatic bone as part of the orbital wall, posteriorly with the temporal bone, and superiorly with the parietal bone.[4][1] These relations position the greater wing centrally within the skull base, bridging the neurocranium and viscerocranium while contributing to the lateral side walls of the cranium.[3][5] The orientation of the greater wing projects upward, outward, and posteriorly from the sphenoid body, integrating into the skull base and side walls to provide structural continuity.[3][4] Its cerebral surface indirectly aids in delineating the middle cranial fossa from the anterior cranial fossa by forming the inferior boundary of the middle fossa, in conjunction with the lesser wings superiorly.[1][6]Borders and articulations

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone possesses four primary borders that enable its articulations with neighboring cranial and facial bones, primarily through fibrous sutures that confer rigidity to the skull while permitting growth during development. These borders form immovable syndesmotic joints, characterized by dense connective tissue that interdigitates the bone edges for enhanced stability. The anterior border articulates with the orbital plate of the frontal bone via the sphenofrontal suture, delineating the posterior limit of the superior orbital fissure and contributing to the lateral orbital rim.[4][3][1] The posterior border connects with the squamous portion of the temporal bone through the sphenosquamosal suture, a vertically oriented seam located lateral to the foramen spinosum, which helps bound the posterior aspect of the middle cranial fossa and the infratemporal fossa. The superior border joins the anteroinferior angle of the parietal bone at the sphenoparietal suture, forming part of the pterion—a key junction where four bones meet—and supporting the lateral wall of the cranial vault. The lateral or inferior border articulates with the frontal process of the zygomatic bone via the sphenozygomatic suture, reinforcing the zygomatic arch and the inferior boundary of the temporal fossa, with occasional minor involvement in the sphenopalatine suture adjacent to the palatine bone.[7][8][9][10] These sutures typically feature serrated, interlocking margins that increase tensile strength and resist shear forces across the skull. They play a role in accommodating brain growth through gradual remodeling, with synostosis (bony fusion) generally commencing in late childhood and completing by adolescence, often around 8–15 years of age depending on the specific suture, after which further expansion is limited.[9][11][12] Anatomical variations in these borders and articulations include the occasional presence of accessory sutures or sutural (wormian) bones, particularly along the sphenozygomatic or sphenoparietal margins, which may arise from irregular ossification patterns. Incomplete fusions or anomalous suture configurations can also occur in congenital conditions, such as isolated craniosynostoses, potentially altering skull morphology and requiring clinical evaluation.[13][14]Surfaces

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone features four primary surfaces—cerebral, temporal, orbital, and infratemporal—each exhibiting unique contours, markings, and structural adaptations that interface with adjacent cranial and facial cavities. These surfaces vary in thickness, generally becoming thinner toward the orbital margin and thicker in the temporal region, with distinctive vascular grooves and muscular ridges tailored to their respective functions.[15][5] The cerebral surface, oriented superiorly, is deeply concave and constitutes a significant portion of the floor of the middle cranial fossa. This surface bears digitate impressions (impressiones digitatae) and cerebral ridges (juga cerebralia) that correspond to the gyri and sulci of the temporal and meningeal lobes of the brain, providing a molded interface for cerebral support. Additionally, it includes shallow sulci that accommodate branches of the middle meningeal vessels, enhancing the vascular accommodation within the cranial vault.[15][3] The temporal surface, also referred to as the lateral surface, presents a convex contour and contributes to the lateral walls of both the temporal and infratemporal fossae. Divided by the infratemporal crest—a prominent ridge running anteroposteriorly—it provides attachment sites for the deep fibers of the temporalis muscle on its superior portion, facilitating masticatory mechanics. The temporal crest itself serves as a key landmark, separating the temporal fossa above from the infratemporal region below, with subtle ridges reinforcing muscle origins.[16][17] The orbital surface is a smooth, quadrilateral thin plate that forms the posterior and lateral wall of the orbit, articulating anteriorly with the zygomatic bone and superiorly with the orbital plate of the frontal bone. Its gently curved contour includes an arcuate line along the superomedial margin, which indirectly borders the superior orbital fissure by separating it from the lesser wing. This surface's minimal markings ensure a streamlined contribution to the orbital cavity, maintaining structural integrity without prominent protrusions.[18][5] The infratemporal surface, directed inferiorly and oriented largely horizontally, forms the roof of the infratemporal fossa in conjunction with the squamous temporal bone. It features the infratemporal crest posteriorly and provides attachment for the superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle, with shallow grooves and ridges accommodating these fibers and facilitating their insertion toward the mandibular condyle. These markings, including subtle vascular impressions, underscore its role in supporting pterygoid muscle dynamics within the deep facial space.[1][19]Foramina and fissures

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone features several key foramina and fissures that serve as passages for neurovascular structures between the cranial cavity and extracranial regions. These openings are primarily located on the infratemporal surface and the margins of the wing, facilitating the transmission of cranial nerves and associated vessels while contributing to the compartmentalization of the skull base.[1] The foramen rotundum is situated at the medial aspect of the greater wing, at its junction with the body of the sphenoid bone, connecting the middle cranial fossa to the pterygopalatine fossa. It transmits the maxillary nerve (CN V2), the artery of the foramen rotundum (a branch of the internal maxillary artery), and occasional emissary veins. This foramen's position underscores its role in directing sensory innervation from the trigeminal ganglion to the midface.[20][21] Positioned posterior to the foramen rotundum on the greater wing, the foramen ovale lies within the floor of the middle cranial fossa and opens into the infratemporal fossa. It conveys the mandibular nerve (CN V3), the accessory meningeal artery, the lesser petrosal nerve, and sometimes an emissary vein. This opening is essential for the passage of motor and sensory fibers supplying the lower face, jaw, and meninges.[20][22] The foramen spinosum, located posterolateral to the foramen ovale in the greater wing, also communicates between the middle cranial fossa and the infratemporal fossa. It transmits the middle meningeal artery and vein, along with the meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve (nervus spinosus). This foramen's vascular contents are clinically notable for their potential involvement in epidural hematomas following trauma.[23][20] The foramen Vesalius, a variable and often inconstant opening, is typically found medial to the foramen ovale within the greater wing of the sphenoid, near the base of the medial pterygoid plate. When present, it transmits emissary veins connecting the cavernous sinus to the pterygoid venous plexus, aiding in venous drainage from the cranial cavity. Its presence occurs in approximately 80% of cases, though it may be absent or asymmetrical without pathological implication.[24][20] The superior orbital fissure forms a cleft between the greater and lesser wings of the sphenoid, at the apex of the orbit, linking the middle cranial fossa to the orbital cavity. It transmits the oculomotor nerve (CN III), trochlear nerve (CN IV), abducens nerve (CN VI), ophthalmic nerve (CN V1), and the superior ophthalmic vein, with additional sympathetic fibers and branches of the inferior ophthalmic vein. This fissure's contents are critical for orbital innervation and venous outflow.[20][25] Inferiorly, the pterygomaxillary fissure arises between the posterior aspect of the maxilla and the greater wing of the sphenoid (specifically the lateral pterygoid plate), connecting the infratemporal fossa to the pterygopalatine fossa. It provides passage for branches of the maxillary artery and associated neurovascular elements, supporting blood supply and innervation to the deep face.[26]Development

Ossification process

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone undergoes a dual ossification process, primarily intramembranous from mesenchymal tissue derived from the lateral plate mesenchyme, with endochondral components contributing at the junction with the sphenoid body.[5][27] Intramembranous ossification begins in the ala temporalis and alar process regions, where mesenchymal cells differentiate directly into osteoblasts to form bone matrix without a cartilaginous intermediate.[27] The endochondral aspect involves prior cartilage formation that calcifies at the medial root near the body.[28] Ossification centers for the greater wing appear during the 8th to 10th gestational week, with the initial center emerging at the root below the future foramen rotundum.[27] Two primary centers develop in the greater wing anlage—one in the ala temporalis laterally and another in the alar process medially—fusing by approximately 12 weeks gestation to form a cohesive structure.[27] Rapid ossification proceeds through the second trimester, with the wing largely formed by membranous bone by late gestation.[27] Postnatally, the greater wings integrate with the sphenoid body, fusing soon after birth with complete consolidation by the end of the first year.[28] Sutures with adjacent bones, such as the temporal and frontal, remain patent for growth and close progressively by puberty.[4] The wing expands laterally through appositional growth at its borders, driven by periosteal deposition influenced by expanding brain volume and masticatory muscle forces.[29]Embryological origins

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone, also known as the alisphenoid or ala temporalis, derives primarily from neural crest cells, with contributions from paraxial mesoderm in the overall sphenoid complex.[1][30] The anlage of the greater wing forms from mesenchymal condensations associated with the presphenoid primordium and mesencephalic mesenchyme, where neural crest cells migrate to populate the lateral aspects of the developing cranial base.[31][30] During the fourth to sixth weeks of embryonic development (Carnegie stages 17–23), the greater wing emerges as lateral outgrowths from the sphenoid body primordium, driven by proliferation of mesenchymal cells surrounding emerging neural structures.[31] This process is influenced by induction from the neural tube, particularly through interactions with the trigeminal and optic nerves, which guide the formation of foramina and shape the mesenchymal condensations.[31] Initial connections to the sphenoid complex form in utero, but fusion of the greater wing to the sphenoid body occurs postnatally, typically soon after birth, with full consolidation by the end of the first year. The patterning of these elements, including anterior-posterior identity along the cranial base, is regulated by HOX genes, which orchestrate the differentiation and positional specification of neural crest-derived mesenchyme.[32] Disruptions in the embryological origins, such as incomplete migration of neural crest cells, can result in anomalies like craniosynostosis due to aberrant suture formation or aplasia/hypoplasia of the greater wing, altering cranial base architecture.[33][34]Function

Structural support

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone forms a significant portion of the floor of the middle cranial fossa, providing essential support for the weight of the temporal lobe of the brain and helping to resist the mechanical stresses imposed by intracranial pressure.[1] This concave cerebral surface, positioned laterally to the sphenoid body, creates a stable platform that accommodates the temporal lobe while maintaining the integrity of the cranial cavity against internal forces generated by cerebrospinal fluid and brain tissue.[35] In addition to its role in the cranial base, the greater wing reinforces the lateral walls of the skull by articulating with the frontal, parietal, and temporal bones through sutures, thereby distributing masticatory forces originating from the temporal fossa across the skull base.[1] Its triangular, winged morphology acts as a structural buttress, linking the orbit to the cranium and preventing collapse under lateral impacts or compressive loads, enhancing its capacity for load-bearing.[35] The greater wing integrates seamlessly with the sphenoid body, contributing to the overall rigidity of the cranium by forming part of its central keystone structure that interconnects multiple cranial elements for enhanced mechanical stability.[1]Attachments and passages

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone serves as a key site for muscular attachments that facilitate mandibular movements essential for mastication. The temporalis muscle attaches to its temporal surface, contributing to the elevation of the mandible during jaw closure.[1] The superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle originates from the infratemporal surface and infratemporal crest of the greater wing, enabling protrusion, depression, and lateral deviation of the mandible to support chewing and grinding motions.[36] Ligamentous attachments on the greater wing provide stability to the temporomandibular joint. The sphenomandibular ligament arises from the angular spine (spina angularis) at the posterior angle of the greater wing and extends to the lingula of the mandible, limiting excessive forward protrusion of the mandible and aiding in joint stabilization during mastication.[37] Several foramina in the greater wing transmit neurovascular structures critical for sensory and motor innervation of the face and oral cavity, as well as vascular supply to intracranial structures. The foramen rotundum transmits the maxillary nerve (CN V2), providing sensory innervation to the midface, nasal cavity, palate, and upper teeth.[3] The foramen ovale conveys the mandibular nerve (CN V3), which supplies sensory innervation to the lower face, tongue, and lower teeth while providing motor innervation to the muscles of mastication; it also transmits the accessory meningeal artery and the lesser petrosal nerve for parasympathetic supply to the parotid gland.[1] The foramen spinosum, posterior to ovale, transmits the middle meningeal artery and vein, which supply arterial blood to the dura mater and drain venous blood from the meninges, along with a meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve.[1] Additionally, emissary veins pass through the variably present foramen of Vesalius (sphenoidal emissary foramen) in the greater wing, facilitating venous drainage from the cavernous sinus to the pterygoid venous plexus and potentially aiding in pressure equalization between intracranial and extracranial venous systems.[38] These passages collectively support trigeminal nerve-mediated sensation and motor control for facial and oral functions, while ensuring vascular nourishment to the dura and meninges.[1]Clinical significance

Trauma and fractures

Fractures of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone typically result from high-impact trauma to the temporal or orbital regions, such as motor vehicle accidents, falls from height, or assaults, which account for the majority of cases. These injuries often occur as part of complex skull base fractures, including Le Fort III patterns that involve separation of the midface from the cranium and extend through the sphenoid. High-energy mechanisms are particularly associated with such fractures, with motor vehicle accidents being a leading cause in up to 50% of instances.[39][40] Common fracture patterns include linear fractures along the junction of the greater wing and sphenoid body, often propagating transversely or obliquely through the orbital surface, and comminuted fractures in severe trauma. Due to the proximity of the carotid canal, these fractures carry a risk of vascular injury, with disruptions to the canal observed in a significant subset of cases. The thin orbital surface of the greater wing contributes to its vulnerability in lateral impacts.[41][42] Immediate consequences encompass cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks through foramina such as the foramen rotundum or ovale, cranial nerve palsies (notably involving the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve, CN V2), and formation of epidural hematomas from venous injury to the sphenoparietal sinus. These effects arise from dural tears and direct compression at the superior orbital fissure or orbital apex. Diagnosis relies on computed tomography (CT) imaging, which demonstrates bony discontinuity and associated soft tissue injuries; such fractures occur in approximately 7-16% of nonpenetrating head injuries, with higher incidence in motor vehicle accidents comprising 10-20% of skull base fractures.[43][41][44]Pathologies and malformations

The greater wing of the sphenoid bone is susceptible to congenital malformations, particularly in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the NF1 gene on chromosome 17.[45] In 4%–11% of NF1 cases, hypoplasia or dysplasia of the greater wing occurs, resulting in temporal lobe herniation into the orbit and subsequent orbital dystopia, often manifesting as pulsatile proptosis and restricted extraocular movements such as esotropia and hypotropia.[45] This malformation arises from dysplastic bone development and can lead to compressive effects on orbital structures without associated optic pathway gliomas in many instances.[45] Additionally, craniosynostosis syndromes like Apert syndrome, driven by FGFR2 mutations, involve premature fusion of the inter-sphenoid synchondrosis around 3 weeks postnatally, restricting anteroventral facial growth and altering the position of the greater wing, contributing to brachycephaly and midface hypoplasia.[46] Fibrous dysplasia is another common benign condition affecting the greater wing, occurring in 10-25% of cases involving the skull and facial bones. It involves replacement of normal bone with fibro-osseous tissue, leading to bony expansion, proptosis, and potential compression of orbital structures or cranial nerves.[47] Tumors affecting the greater wing include sphenoid wing meningiomas, which are typically slow-growing, dural-based lesions classified as WHO grade I in approximately 85% of cases.[48] These benign tumors often invade the bone, causing hyperostosis of the sphenoid wing with irregular edges and extension into the orbit, leading to proptosis in about 74% of patients and restriction of extraocular movements.[48] The hyperostosis results in volumetric bone overgrowth, with surgical resection often removing a median of 86% of affected bone to alleviate symptoms.[48] Other non-traumatic pathologies include erosive lesions from cholesteatoma, a cystic squamous epithelium-lined mass filled with keratin debris that can develop in the sphenoid wing, causing bony remodeling and orbital mass effect with proptosis and diplopia.[49] Metastatic lesions from primaries such as breast, prostate, or lung cancer may also erode the greater wing, presenting as osteolytic defects on imaging.[50] Infections like osteomyelitis, often secondary to invasive fungal sinusitis such as mucormycosis in immunocompromised patients, can involve the greater wing through osteolysis and abnormal enhancement, with spread facilitated via skull base foramina like the foramen lacerum.[51] Surgical management of these pathologies frequently employs the pterional craniotomy approach for tumor resection or malformation reconstruction, allowing access to the sphenoid wing while minimizing brain retraction.[48] Key risks include optic nerve damage from compression or manipulation during optic canal decompression, potentially leading to persistent visual deficits in up to 5% of cases, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula, with complication rates ranging from 5% to 10% across supratentorial craniotomies.[52][53] Postoperative visual stabilization is more likely with proactive optic nerve decompression, though recurrence rates for meningiomas remain around 22% despite gross-total resection in 20%–43% of attempts.[48]Comparative anatomy

In mammals

In therian mammals, the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, known as the alisphenoid, manifests as broad lateral expansions arising from the sphenoid body, which collectively form the floor of the middle cranial fossa and contribute to the lateral walls of the orbit.[54] These wing-like structures are a conserved feature across all therian mammals, providing essential structural integrity to the neurocranium while enclosing critical neurovascular elements.[55] Variations in the alisphenoid's form reflect adaptations to diverse cranial architectures and lifestyles among mammals. In carnivores, such as dogs, the alisphenoid is notably robust and expansive, extending to form a significant portion of the temporal fossa and offering enhanced attachment sites for powerful masticatory muscles like the temporalis and masseter, which support the biomechanical demands of predation and bone-crushing.[54] Conversely, in rodents, the alisphenoid remains prominent within their compact skulls, facilitating attachments for pterygoid muscles essential for gnawing, though its relative proportions are scaled to accommodate the streamlined cranial design typical of these species.[54] In primates, the alisphenoid is comparatively enlarged, accommodating the expanded braincase by broadening the middle cranial fossa and enhancing orbital support.[56] Functionally, the alisphenoid exhibits strong conservation across mammals, consistently featuring foramina such as the rotundum and ovale that transmit branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) and associated meningeal vessels, ensuring reliable sensory innervation and vascular supply to the face and meninges.[54] This arrangement underscores its role in protecting and facilitating neural pathways amid varying cranial sizes. Evolutionarily, ossification patterns of the alisphenoid are similarly conserved, predominantly intramembranous within the membrane surrounding the cranial cavity, though incorporating cartilaginous elements in some regions, which fuse with adjacent bones during development.[55][54]In other vertebrates

In reptiles, the epipterygoid serves as the primary homologue to the mammalian alisphenoid (greater wing of the sphenoid), contributing to the formation of the lateral wall of the braincase.[57] It ossifies separately from the prootic and is less expanded compared to the mammalian condition, reflecting a more primitive configuration adapted for supporting the temporal region and jaw musculature.[58] In squamates, for instance, the epipterygoid ossifies to enclose the braincase laterally, with membrane bone development occurring deep to the masticatory muscles.[59] In birds, equivalents to the greater wing are incorporated into the fused cranium through the orbital cartilages and basal plate elements of the chondrocranium, which undergo extensive reduction to facilitate a lightweight skull optimized for flight.[60] The posterior orbital cartilage, derived from the pila antotica, fuses with surrounding structures but contributes minimally to the orbital wall, often resorbing or persisting only as a narrow strip in species like ostriches or penguins.[60] This reduction eliminates many discrete bony elements, resulting in a kinetically flexible yet compact cranium with fenestrated interorbital septa.[61] In amphibians and fish, structures homologous to the greater wing are rudimentary or absent, with sphenoid-like elements primarily existing as cartilaginous components of the chondrocranium rather than fully ossified bones.[62] The parasphenoid, a dermal bone along the ventral skull base, acts as an evolutionary precursor in these groups, providing midline support but lacking the lateral expansions seen in higher vertebrates; in fish, it ossifies intramembranously without cartilaginous intermediaries, while in amphibians like urodeles, prootic extensions form partial alisphenoid laminae from cartilage.[63] This cartilaginous foundation underscores the primitive state of the neurocranium in aquatic forms. Key differences between these vertebrate groups and mammals include fewer foramina perforating the lateral braincase walls in lower vertebrates, such as the absence of distinct separations for cranial nerves V2 and V3 in amphibians, which simplifies neural passages compared to the multiple openings in the mammalian greater wing.[62] Adaptations also diverge based on locomotion: aquatic species like fish rely on a flexible, cartilaginous chondrocranium for buoyancy and minimal structural demands, whereas terrestrial reptiles show enhanced ossification for robust jaw support, contrasting with the mammalian emphasis on encephalization and orbital protection.[64]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Osteology_of_the_Reptiles/Chapter_1