Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

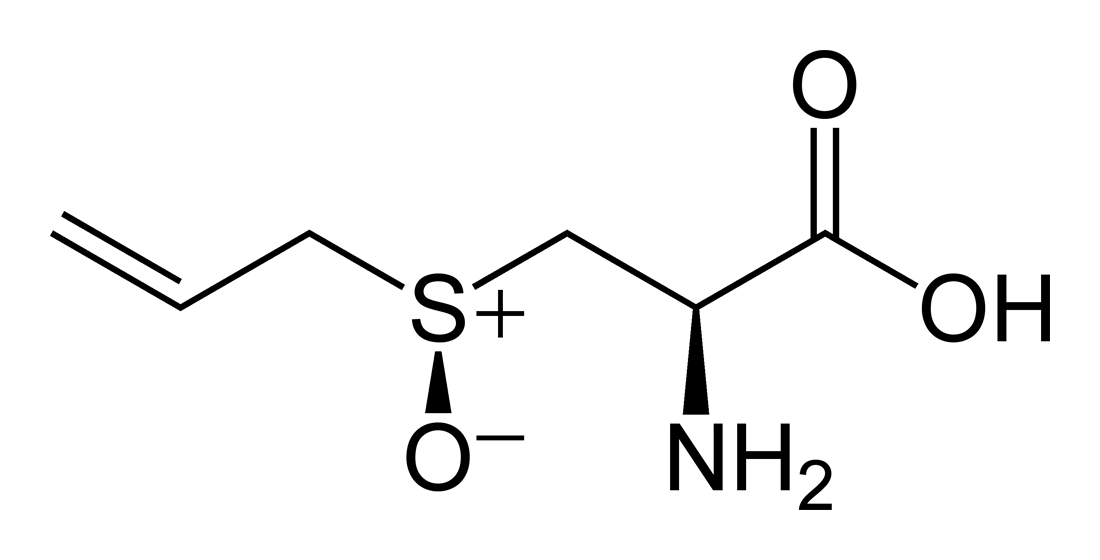

Alliin

View on Wikipedia | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R)-2-Amino-3-[(S)-(prop-2-ene-1-sulfinyl)]propanoic acid | |

| Other names

3-(2-Propenylsulfinyl)alanine

(S)-3-(2-Propenylsulfinyl)-L-alanine 3-[(S)-Allylsulfinyl]-L-alanine S-Allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.008.291 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H11NO3S | |

| Molar mass | 177.22 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White to off white crystalline powder |

| Melting point | 163–165 °C (325–329 °F) |

| Soluble | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H315, H319, H335 | |

| P261, P264, P271, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Alliin /ˈæli.ɪn/ is a sulfoxide that is a natural constituent of fresh garlic.[1] It is a derivative of the amino acid cysteine. When fresh garlic is chopped or crushed, the enzyme alliinase converts alliin into allicin, which is responsible for the aroma of fresh garlic. Allicin and other thiosulfinates in garlic are unstable and form a number of other compounds, such as diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (DADS) and diallyl trisulfide (DAT), dithiins and ajoene.[2] Garlic powder is not a source of alliin, nor is fresh garlic upon maceration, since the enzymatic conversion to allicin takes place in the order of seconds.

Alliin was the first natural product found to have both carbon- and sulfur-centered stereochemistry.[3]

Chemical synthesis

[edit]The first reported synthesis, by Stoll and Seebeck in 1951,[4] begins the alkylation of L-cysteine with allyl bromide to form deoxyalliin. Oxidation of this sulfide with hydrogen peroxide gives both diastereomers of L-alliin, differing in the orientation of the oxygen atom on the sulfur stereocenter.

A newer route, reported by Koch and Keusgen in 1998,[5] allows stereospecific oxidation using conditions similar to the Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation. The chiral catalyst is produced from diethyl tartrate and titanium isopropoxide.

Medical exploration

[edit]This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (July 2024) |

Garlic has been used since antiquity for conditions now associated with oxidative stress (production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)).[citation needed] In an in vitro test, garlic powder showed antioxidant properties, and alliin showed good hydroxyl radical-scavenging effect.[6] Alliin has also been found to affect immune responses in blood cells in vitro.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ Iberl, B; Winkler, G; Müller, B; Knobloch, K (1990). "Quantitative Determination of Allicin and Alliin from Garlic by HPLC". Planta Med. 56 (3): 320–326. Bibcode:1990PlMed..56..320I. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960969. PMID 17221429. S2CID 30268881.

- ^ Amagase, Harunobu; Petesch, Brenda L.; Matsuura, Hiromichi; Kasuga, Shigeo; Itakura, Yoichi (2001). "Intake of Garlic and Its Bioactive Components". The Journal of Nutrition. 131 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 955S – 962S. doi:10.1093/jn/131.3.955s. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 11238796.

- ^ Block, E (2009). Garlic and Other Alliums: The lore and the science. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 100–106.

- ^ Stoll, A; Seeback, E (1951). Chemical investigations on alliin, the specific principle of garlic. Advances in Enzymology and Related Subjects of Biochemistry. Vol. 11. pp. 377–400. doi:10.1002/9780470122563.ch8. ISBN 9780470122563. PMID 24540596.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Koch; Keusgen (1998). "Diastereoselective synthesis of alliin by an asymmetric sulfur oxidation". Pharmazie. 53 (668–671). doi:10.1002/chin.199904184.

- ^ Kourounakis, PN; Rekka, EA (November 1991). "Effect on active oxygen species of alliin and Allium sativum (garlic) powder". Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 74 (2): 249–252. PMID 1667340.

- ^ Salman, H; Bergman, M; Bessler, H; Punsky, I; Djaldetti, M (September 1999). "Effect of a garlic derivative (alliin) on peripheral blood cell immune responses". Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 21 (9): 589–597. doi:10.1016/S0192-0561(99)00038-7. PMID 10501628.