Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alpine orogeny

View on Wikipedia

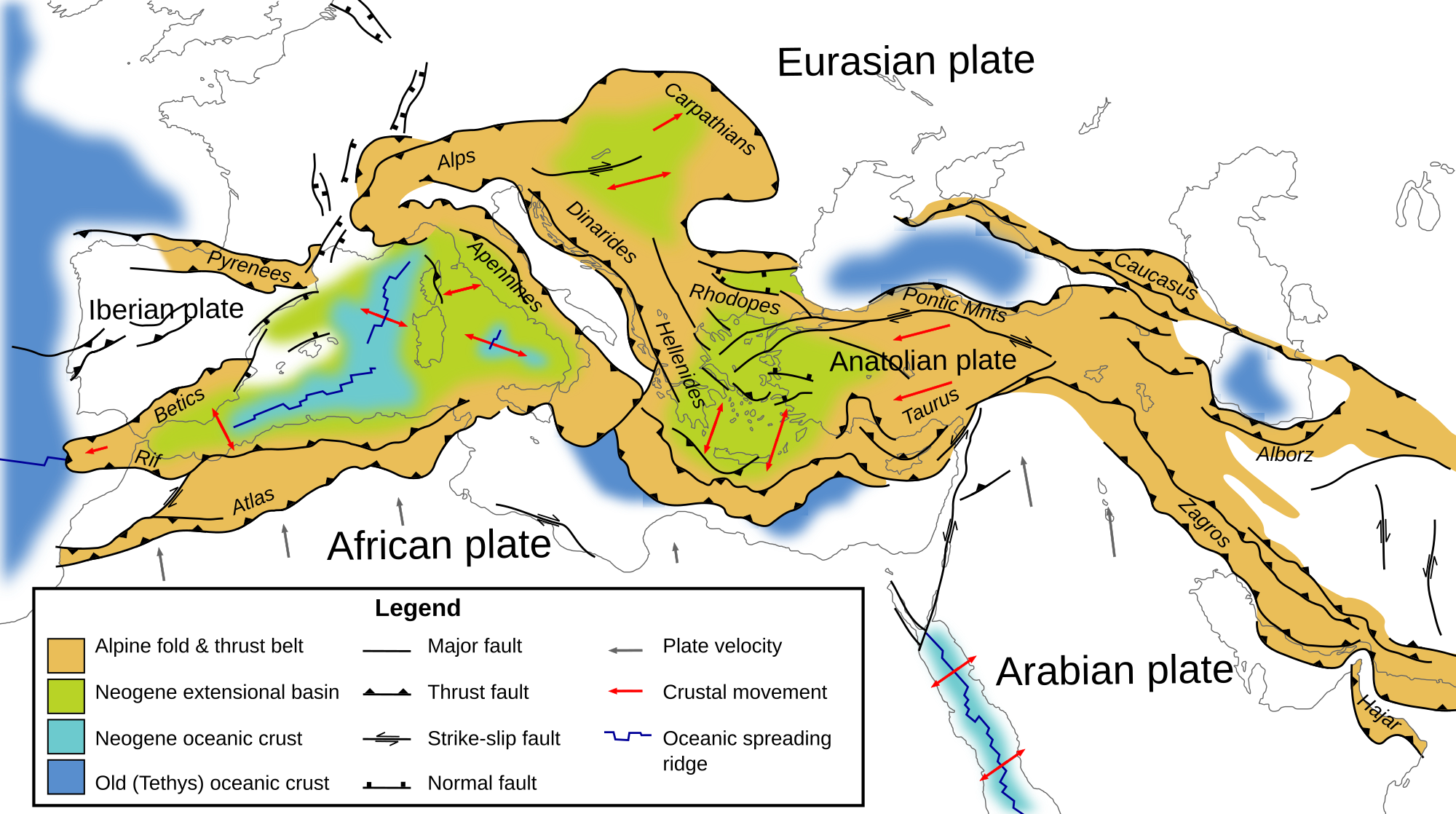

The Alpine orogeny, sometimes referred to as the Alpide orogeny, is an orogenic phase in the Late Mesozoic[1] and the current Cenozoic which has formed the mountain ranges of the Alpide belt.

Cause

[edit]The Alpine orogeny was caused by the African continent, the Arabian Peninsula, the Indian subcontinent, and the Cimmerian plate colliding with Eurasia in the north. Convergent movements between the African, Arabian and Indian plates from the south, and the Eurasian plate and the Anatolian sub-plate from the north – as well as many smaller (micro)plates – had already begun during the early Cretaceous, but the major phases of mountain building began during the Paleocene to the Eocene. The process continues currently in some of the Alpide mountain ranges.[citation needed]

The Alpine orogeny is considered one of the three major phases of orogeny in Europe that define the geology of that continent, along with the Caledonian orogeny that formed the Old Red Sandstone Continent when the continents Baltica and Laurentia collided in the early Paleozoic, and the Hercynian or Variscan orogeny that formed Pangaea when Gondwana and the Old Red Sandstone Continent collided in the middle to late Paleozoic.[citation needed]

Mountain ranges

[edit]From west to east, mountains include the Atlas, the Rif, the Baetic Cordillera, the Cantabrian Mountains, the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Apennines, the Dinaric Alps, the Albanides, the Pindus, the Carpathians, the Balkanides (the Balkan Mountains and Rila-Rhodope massifs), the Pontic Mountains, the Taurus, the Antitaurus, the Armenian Highlands, the Caucasus Mountains, the Alborz, the Zagros Mountains, the Hajar, the Hindu Kush, the Pamir, the Karakoram, and the Himalayas.[2]

Sometimes other names occur to describe the formation of separate mountain ranges: e.g., "Carpathian orogeny" for the Carpathians, "Hellenic orogeny" for the Pindus, "Altai orogeny" for the Altai Mountains, and "Himalayan orogeny" for the Himalayas.

Formation of geological features

[edit]The Alpine orogeny has also led to the formation of more distant and smaller geological features such as the Weald–Artois Anticline in Southern England and northern France, the remains of which can be seen in the chalk ridges of the North and South Downs in Southern England. Its effects are particularly visible on the Isle of Wight, where the Chalk Group and overlying Eocene strata are folded to near-vertical, as seen in exposures at Alum Bay and Whitecliff Bay, and on the Dorset coast near Lulworth Cove.[3] Stresses arising from the Alpine orogeny caused the Cenozoic uplift of the Sudetes mountain range[4] and possibly faulted rocks as far away as Öland in southern Sweden during the Paleocene.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Moores, E.M., Fairbridge, R.W. (Editors), 1998: Encyclopedia of European and Asian Regional Geology. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series, London, 825 pp.

- ^ Petrović, Dragutin; Manojlović, Predrag (2003). Geomorfologija (in Serbian). Belgrade: University of Belgrade Faculty of Geography. p. 60. ISBN 86-82657-32-5.

- ^ Parrish, Randall R.; Parrish, Claire M.; Lasalle, Stephanie (May 2018). "Vein calcite dating reveals Pyrenean orogen as cause of Paleogene deformation in southern England". Journal of the Geological Society. 175 (3): 425–442. Bibcode:2018JGSoc.175..425P. doi:10.1144/jgs2017-107. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 134690307.

- ^ Migoń, Piotr (2011). "Geomorphic Diversity of the Sudetes - Effects of the structure and global change superimposed". Geographia Polonica. 2: 93–105.

- ^ Goodfellow B.W.; Viola G.; Bingen B.; Nuriel P.; Kylander-Clark A. (2017). "Palaeocene faulting in SE Sweden from U–Pb dating of slickenfibre calcite". Terra Nova. 29 (5): 321–328. Bibcode:2017TeNov..29..321G. doi:10.1111/ter.12280. S2CID 134545534.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Alpine orogeny at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alpine orogeny at Wikimedia Commons