Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Africa

View on Wikipedia

| Area | 30,370,000 km2 (11,730,000 sq mi) (2nd) |

|---|---|

| Population | |

| Population density | 46.1/km2 (119.4/sq mi) (2021) |

| GDP (PPP) | $10.77 trillion (2025 est; 4th)[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.82 trillion (2025 est; 5th)[4] |

| GDP per capita | $1,920 (Nominal; 2025 est; 6th)[5] |

| Religions |

|

| Demonym | African |

| Countries | 54 recognised states, 2 partially recognised states, 4 dependent territories |

| Dependencies | External (4) |

| Languages | 1250–3000 native languages |

| Time zones | UTC-1 to UTC+4 |

| Largest cities | Largest urban areas: |

| ^ A: African people often combine the practice of their traditional beliefs with the practice of Abrahamic religions.[7][8] | |

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surface area.[9] With nearly 1.4 billion people as of 2021, it accounts for about 18% of the world's human population. Africa's population is the youngest among all the continents;[10][11] the median age in 2012 was 19.7, when the worldwide median age was 30.4.[12] Based on 2024 projections, Africa's population will exceed 3.8 billion people by 2100.[13] Africa is the least wealthy inhabited continent per capita and second-least wealthy by total wealth, ahead of Oceania. Scholars have attributed this to different factors including geography, climate,[14] corruption,[14] colonialism, the Cold War,[15][16] and neocolonialism. Despite this low concentration of wealth, recent economic expansion and a large and young population make Africa an important economic market in the broader global context, and Africa has a large quantity of natural resources.

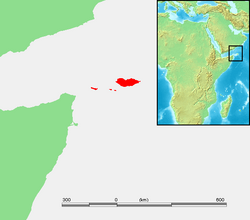

Africa straddles the equator and the prime meridian. The continent is surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Arabian Plate and the Gulf of Aqaba to the northeast, the Indian Ocean to the southeast and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Yemen have parts of their territories located on African geographical soil, mostly in the form of islands.

The continent includes Madagascar and various archipelagos. It contains 54 fully recognised sovereign states, eight cities and islands that are part of non-African states, and two de facto independent states with limited or no recognition. This count does not include Malta and Sicily, which are geologically part of the African continent. Algeria is Africa's largest country by area, and Nigeria is its largest by population. African nations cooperate through the establishment of the African Union, which is headquartered in Addis Ababa.

Africa is highly biodiverse;[17] it is the continent with the largest number of megafauna species, as it was least affected by the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna. However, Africa is also heavily affected by a wide range of environmental issues, including desertification, deforestation, water scarcity, and pollution. These entrenched environmental concerns are expected to worsen as climate change impacts Africa. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has identified Africa as the continent most vulnerable to climate change.[18][19]

The history of Africa is long, complex, and varied, and has often been under-appreciated by the global historical community.[20] In African societies the oral word is revered, and they have generally recorded their history via oral tradition, which has led anthropologists to term them "oral civilisations", contrasted with "literate civilisations" which pride the written word.[a][23]: 142–143 African culture is rich and diverse both within and between the continent's regions, encompassing art, cuisine, music and dance, religion, and dress.

Africa, particularly Eastern Africa, is widely accepted to be the place of origin of humans and the Hominidae clade, also known as the great apes. The earliest hominids and their ancestors have been dated to around 7 million years ago, and Homo sapiens (modern human) are believed to have originated in Africa 350,000 to 260,000 years ago.[b] In the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE Ancient Egypt, Kerma, Punt, and the Tichitt Tradition emerged in North, East and West Africa, while from 3000 BCE to 500 CE the Bantu expansion swept from modern-day Cameroon through Central, East, and Southern Africa, displacing or absorbing groups such as the Khoisan and Pygmies. Some African empires include Wagadu, Mali, Songhai, Sokoto, Ife, Benin, Asante, the Fatimids, Almoravids, Almohads, Ayyubids, Mamluks, Kongo, Mwene Muji, Luba, Lunda, Kitara, Aksum, Ethiopia, Adal, Ajuran, Kilwa, Sakalava, Imerina, Maravi, Mutapa, Rozvi, Mthwakazi, and Zulu. Despite the predominance of states, many societies were heterarchical and stateless.[c] Slave trades created various diasporas, especially in the Americas. From the late 19th century to early 20th century, driven by the Second Industrial Revolution, most of Africa was rapidly conquered and colonised by European nations, save for Ethiopia and Liberia.[32] European rule had significant impacts on Africa's societies, and colonies were maintained for the purpose of economic exploitation and extraction of natural resources. Most present states emerged from a process of decolonisation following World War II, and established the Organisation of African Unity in 1963, the predecessor to the African Union.[33] The nascent countries decided to keep their colonial borders, with traditional power structures used in governance to varying degrees.

Etymology

[edit]Afri was a Latin name used to refer to the inhabitants of what was then known as northern Africa, located west of the Nile river, and in its widest sense referring to all lands south of the Mediterranean, also known as Ancient Libya.[34][35] This name seems to have originally referred to a native Libyan tribe, an ancestor of modern Berbers;[36] see Terence for discussion. The name had usually been connected with the Phoenician word ʿafar meaning "dust",[37] but a 1981 hypothesis[38] has asserted that it stems from the Berber word ifri (plural ifran) meaning "cave", in reference to cave dwellers.[39] The same word[39] may be found in the name of the Banu Ifran from Algeria and Tripolitania, a Berber tribe originally from Yafran (also known as Ifrane) in northwestern Libya,[40] as well as the city of Ifrane in Morocco.

Under Roman rule, Carthage became the capital of the province then named Africa Proconsularis, following the Roman victory over the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War in 146 BC, which also included the coastal part of modern Libya.[41] The Latin suffix -ica can sometimes be used to denote a land (e.g., in Celtica from Celtae, as used by Julius Caesar). The later Muslim region of Ifriqiya, following its conquest of the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire's Exarchatus Africae, also preserved a form of the name.

According to the Romans, Africa lies to the west of Egypt, while "Asia" was used to refer to Anatolia and lands to the east. A definite line was drawn between the two continents by the geographer Ptolemy (85–165 CE), indicating Alexandria along the Prime Meridian and making the isthmus of Suez and the Red Sea the boundary between Asia and Africa. As Europeans came to understand the real extent of the continent, the idea of "Africa" expanded with their knowledge.

Other etymological hypotheses have been postulated for the ancient name "Africa":

- The 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (Ant. 1.15) asserted that it was named for Epher, grandson of Abraham according to Gen. 25:4, whose descendants, he claimed, had invaded Libya.

- Isidore of Seville in his 7th-century Etymologiae XIV.5.2. suggests "Africa" comes from the Latin aprica, meaning "sunny".

- Massey, in 1881, stated that Africa is derived from the Egyptian af-rui-ka, meaning "to turn toward the opening of the Ka." The Ka is the energetic double of every person and the "opening of the Ka" refers to a womb or birthplace. Africa would be, for the Egyptians, "the birthplace."[42]

- Michèle Fruyt in 1976 proposed[43] linking the Latin word with africus "south wind", which would be of Umbrian origin and mean originally "rainy wind".

- Robert R. Stieglitz of Rutgers University in 1984 proposed: "The name Africa, derived from the Latin *Aphir-ic-a, is cognate to Hebrew Ophir ['rich']."[44]

- Ibn Khallikan and some other historians claim that the name of Africa came from a Himyarite king called Afrikin ibn Kais ibn Saifi ("Afrikus son of Abraham") who subdued Ifriqiya.[45][46][47]

- Arabic afrīqā (feminine noun) and ifrīqiyā, now usually pronounced afrīqiyā (feminine) 'Africa', from 'afara [' = 'ain, not 'alif] 'to be dusty' from 'afar 'dust, powder' and 'afir 'dried, dried up by the sun, withered' and 'affara 'to dry in the sun on hot sand' or 'to sprinkle with dust'.[48]

- Possibly Phoenician faraqa in the sense of 'colony, separation'.[49]

History

[edit]History in Africa

[edit]In accordance with African cosmology, African historical consciousness viewed historical change and continuity, order and purpose within the framework of man and his environment, the gods, and his ancestors, and he believed himself part of a holistic spiritual entity.[50] In African societies, the historical process is largely a communal one, with eyewitness accounts, hearsay, reminiscences, and occasionally visions, dreams, and hallucinations crafted into narrative oral traditions which are performed and transmitted through generations.[51]: 12 : 48 In oral traditions time is sometimes mythical and social, and ancestors were considered historical actors.[d]: 43–53 Mind and memory shapes traditions, as events are condensed over time and crystallise into clichés.[53]: 11 Oral tradition can be exoteric or esoteric. It speaks to people according to their understanding, unveiling itself in accordance with their aptitudes.[54]: 168 In African epistemology, the epistemic subject "experiences the epistemic object in a sensuous, emotive, intuitive, abstractive understanding, rather than through abstraction alone, as is the case in Western epistemology" to arrive at a "complete knowledge", and as such oral traditions, music, proverbs, and the like were used in the preservation and transmission of knowledge.[55]

Prehistory

[edit]

Africa is considered by most paleoanthropologists to be the oldest inhabited territory on Earth, with the Human species originating from the continent.[56] During the mid-20th century, anthropologists discovered many fossils and evidence of human occupation perhaps as early as seven million years ago (Before present, BP). Fossil remains of several species of early apelike humans thought to have evolved into modern humans, such as Australopithecus afarensis radiometrically dated to approximately 3.9–3.0 million years BP,[57] Paranthropus boisei (c. 2.3–1.4 million years BP)[58] and Homo ergaster (c. 1.9 million–600,000 years BP) have been discovered.[9]

After the evolution of Homo sapiens approximately 350,000 to 260,000 years BP in Africa,[25][26][27][28] the continent was mainly populated by groups of hunter-gatherers.[59][60] These first modern humans left Africa and populated the rest of the globe during the Out of Africa II migration dated to approximately 50,000 years BP, exiting the continent either across Bab-el-Mandeb over the Red Sea,[61][62] the Strait of Gibraltar in Morocco,[63][64] or the Isthmus of Suez in Egypt.[65]

Other migrations of modern humans within the African continent have been dated to that time, with evidence of early human settlement found in Southern Africa, Southeast Africa, North Africa, and the Sahara.[66]

Emergence of civilisation

[edit]

The size of the Sahara has historically been extremely variable, with its area rapidly fluctuating and at times disappearing depending on global climatic conditions.[67] At the end of the Ice ages, estimated to have been around 10,500 BC, the Sahara had again become a green fertile valley, and its African populations returned from the interior and coastal highlands in Africa, with rock art paintings depicting a fertile Sahara and large populations discovered in Tassili n'Ajjer dating back perhaps 10 millennia.[68] However, the warming and drying climate meant that by 5,000 BC, the Sahara region was becoming increasingly dry and hostile. Around 3500 BC, due to a tilt in the Earth's orbit, the Sahara experienced a period of rapid desertification.[69] The population trekked out of the Sahara region towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract where they made permanent or semi-permanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in Central and Eastern Africa. Since this time, dry conditions have prevailed in Eastern Africa and, increasingly during the last 200 years, in Ethiopia.

The domestication of cattle in Africa preceded agriculture and seems to have existed alongside hunter-gatherer cultures. It is speculated that by 6,000 BC, cattle were domesticated in North Africa.[70] In the Sahara-Nile complex, people domesticated many animals, including the donkey and a small screw-horned goat that was common from Algeria to Nubia. Between 10,000 and 9,000 BC, pottery was independently invented in the region of Mali in the savannah of West Africa.[71][72] In the steppes and savannahs of the Sahara and Sahel in Northern West Africa, people possibly ancestral to modern Nilo-Saharan and Mandé cultures started to collect wild millet,[73] around 8,000 to 6,000 BC. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton were also collected.[74]: 64–75 Sorghum was first domesticated in Eastern Sudan around 4,000 BC, in one of the earliest instances of agriculture in human history. Its cultivation would gradually spread across Africa, before spreading to India around 2000 BC.[75][76]

People around modern-day Mauritania started making pottery and built stone settlements (e.g., Tichitt, Oualata). Fishing, using bone-tipped harpoons, became a major activity in the numerous streams and lakes formed from the increased rains.[77] In West Africa, the wet phase ushered in an expanding rainforest and wooded savanna from Senegal to Cameroon. Between 9,000 and 5,000 BC, Niger–Congo speakers domesticated the oil palm and raffia palm. Black-eyed peas and voandzeia (African groundnuts), were domesticated, followed by okra and kola nuts. Since most of the plants grew in the forest, the Niger–Congo speakers invented polished stone axes for clearing forest.[74]

Around 4,000 BC, the Saharan climate started to become drier at an exceedingly fast pace.[78] This climate change caused lakes and rivers to shrink significantly and caused increasing desertification. This, in turn, decreased the amount of land conducive to settlements and encouraged migrations of farming communities to the more tropical climate of West Africa.[78] During the first millennium BC, a reduction in wild grain populations related to changing climate conditions facilitated the expansion of farming communities and the rapid adoption of rice cultivation around the Niger River.[79][80]

By the first millennium BC, ironworking had been introduced in Northern Africa. Around that time it also became established in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, either through independent invention there or diffusion from the north[81][82] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 AD, having lasted approximately 2,000 years,[83] and by 500 BC, metalworking began to become commonplace in West Africa. Ironworking was fully established by roughly 500 BC in many areas of East and West Africa, although other regions did not begin ironworking until the early centuries AD. Copper objects from Egypt, North Africa, Nubia, and Ethiopia dating from around 500 BC have been excavated in West Africa, suggesting that Trans-Saharan trade networks had been established by this date.[78]

4th millennium BC – 6th century AD

[edit]Northeast Africa

[edit]

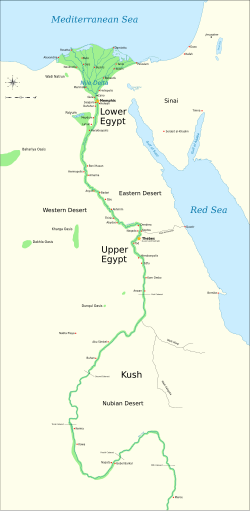

From 3500 BC, nomes (ruled by nomarchs) coalesced to form the kingdoms of Lower Egypt and Upper Egypt in northeast Africa. Around 3100 BC Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egypt to unify Egypt under the 1st dynasty, with the process of consolidation and assimilation completed by the time of the 3rd dynasty who formed the Old Kingdom of Egypt in 2686 BC.[84]: 62–63 The Kingdom of Kerma emerged around this time to become the dominant force in Nubia, controlling territory as large as Egypt between the 1st and 4th cataracts of the Nile.[85][86]

The 4th dynasty oversaw the height of the Old Kingdom, and constructed many great pyramids. Under the 6th dynasty power gradually decentralised to the nomarchs, culminating in the disintegration of the kingdom, exacerbated by drought and famine, thus commencing the First Intermediate Period in 2200 BC. This shattered state would last until 2055 BC when the 11th dynasty, based in Thebes, conquered the others to form the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, with the 12th dynasty expanding into Lower Nubia at the expense of Kerma.[84]: 68–71 In 1700 BC, the Middle Kingdom fractured in two, ushering in the Second Intermediate Period. The Hyksos, a militaristic people from Palestine, invaded and conquered Lower Egypt, while Kerma coordinated invasions deep into Egypt to reach its greatest extent.[87]

In 1550 BC, the 18th dynasty expelled the Hyksos, and established the New Kingdom of Egypt. Using the advanced military technology the Hyksos had brought, the New Kingdom conquered the Levant from the Canaanites, Mittani, Amorites, and Hittites, and extinguished Kerma, incorporating Nubia into the empire, and sending the Egyptian empire into its golden age.[84]: 73 Internal struggles, drought, famine, and invasions by a confederation of seafaring peoples contributed to the New Kingdom's collapse in 1069 BC, commencing the Third Intermediate Period.[84]: 76–77

Egypt's collapse liberated the more Egyptianised Kingdom of Kush in Nubia, who manoeuvred into power in Upper Egypt and conquered Lower Egypt in 754 BC to form the Kushite Empire. The Kushites ruled for a century and oversaw a revival in pyramid building, until they were driven out of Egypt by the Assyrians in 663 BC in reprisal for their expansion towards the Assyrian Empire.[88] The Assyrians installed a puppet dynasty that later gained independence and once more unified Egypt, until they were conquered by the Achaemenid Empire in 525 BC.[84]: 77 Egypt regained independence under the 28th dynasty in 404 BC but they were reconquered by the Achaemenids in 343 BC. The conquest of Achaemenid Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 BC marked the beginning of Hellenistic rule and the installation of the Macedonian Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt.[89]: 119

The Ptolemaics lost their holdings outside of Africa to the Seleucids in the Syrian Wars, expanded into Cyrenaica and subjugated Kush in the 3rd century BC. In the 1st century BC, Ptolemaic Egypt became entangled in a Roman civil war, leading to its conquest by the Romans in 30 BC. The Crisis of the Third Century in the Roman Empire freed the Levantine city state of Palmyra, which conquered Egypt; their brief rule ended when they were reconquered by the Romans. In the midst of this, Kush regained independence from Egypt, and they would persist as a major regional power until, having been weakened from internal rebellion amid worsening climatic conditions, invasions by Aksum and the Noba caused their disintegration into Makuria, Alodia, and Nobatia in the 5th century AD. The Romans managed to hold on to Egypt for the rest of the ancient period.

Horn of Africa

[edit]

In the Horn of Africa, there was the Land of Punt, a kingdom on the Red Sea, likely located in modern-day Eritrea or northern Somaliland.[90] The Ancient Egyptians initially traded via middle-men with Punt until in 2350 BC when they established direct relations. They would become close trading partners for over a millennium. Towards the end of the ancient period, northern Ethiopia and Eritrea bore the Kingdom of D'mt beginning in 980 BC. In modern-day Somalia and Djibouti there was the Macrobian Kingdom, with archaeological discoveries indicating the possibility of other unknown sophisticated civilisations at this time.[91][92] After D'mt's fall in the 5th century BC the Ethiopian Plateau came to be ruled by numerous smaller unknown kingdoms who experienced strong south Arabian influence, until the growth and expansion of Aksum in the 1st century BC.[93] Along the Horn's coast there were many ancient Somali city-states that thrived off of the wider Red Sea trade and transported their cargo via beden, exporting myrrh, frankincense, spices, gum, incense, and ivory, with freedom from Roman interference causing Indians to give the cities a lucrative monopoly on cinnamon from ancient India.[94]

The Kingdom of Aksum grew from a principality into a major power on the trade route between Rome and India through conquering its unfortunately unknown neighbours, gaining a monopoly on Indian Ocean trade in the region. Aksum's rise had them rule over much of the regions from Lake Tana to the valley of the Nile, and they further conquered parts of the ailing Kingdom of Kush, led campaigns against the Noba and Beja peoples, and expanded into South Arabia.[95][96][97] This led the Persian prophet Mani to consider Aksum as one of the four great powers of the 3rd century AD alongside Persia, Rome, and China.[98] In the 4th century AD Aksum's king converted to Christianity and Aksum's population, who had followed syncretic mixes of local beliefs, slowly followed. The end of the 5th century saw Aksum allied with the Byzantine Empire, who viewed themselves as defenders of Christendom, balanced against the Sassanid Empire and the Himyarite Kingdom in Arabia.

Northwest Africa

[edit]

The Maghreb and Ifriqiya were mostly cut off from the cradle of civilisation in Egypt by the Libyan desert, exacerbated by Egyptian boats being tailored to the Nile and not coping well in the open Mediterranean Sea. This caused its societies to develop contiguous to those of Southern Europe, until Phoenician settlements came to dominate the most lucrative trading locations in the Gulf of Tunis.[99]: 247 Phoenician settlements subsequently grew into Ancient Carthage after gaining independence from Phoenicia in the 6th century BC, and they would build an extensive empire and a strict mercantile network, all secured by one of the largest and most powerful navies in the ancient Mediterranean.[99]: 251–253 Carthage would meet its demise in the Punic Wars against the expansionary Roman Republic, however momentum in these wars was not linear, with Carthage initially experiencing considerable success in the Second Punic War following Hannibal's infamous crossing of the alps into northern Italy.[99]: 256–257 Their defeat and subsequent collapse of their empire would produce two further polities in the Maghreb; Numidia, which had assisted the Romans in the Second Punic War, Mauretania, a Mauri tribal kingdom and home of the legendary King Atlas, and various tribes such as Garamantes, Musulamii, and Bavares. The Third Punic War would result in Carthage's total defeat in 146 BC and the Romans established the province of Africa, with Numidia assuming control of many of Carthage's African ports. Towards the end of the 2nd century BC Mauretania fought alongside Numidia's Jugurtha in the Jugurthine War against the Romans after he had usurped the Numidian throne from a Roman ally. Together they inflicted heavy casualties that quaked the Roman Senate, with the war only ending inconclusively when Mauretania's Bocchus I sold out Jugurtha to the Romans.[99]: 258

At the turn of the millennium, they both would face the same fate as Carthage and be conquered by the Romans who established Mauretania and Numidia as provinces of their empire, while Musulamii, led by Tacfarinas, and Garamantes were eventually defeated in war in the 1st century AD however weren't conquered.[100]: 261–262 In the 5th century AD the Vandals conquered north Africa precipitating the fall of Rome. Swathes of indigenous peoples would regain self-governance in the Mauro-Roman Kingdom and its numerous successor polities in the Maghreb, namely the kingdoms of Ouarsenis, Aurès, and Altava. The Vandals ruled Ifriqiya for a century until Byzantine reconquest in the early 6th century AD. The Byzantines and the Berber kingdoms fought minor inconsequential conflicts, such as in the case of Garmul, however largely coexisted.[100]: 284 Further inland to the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa were the Sanhaja in modern-day Algeria, a broad grouping of three groupings of tribal confederations, one of which is the Masmuda grouping in modern-day Morocco, along with the nomadic Zenata; their composite tribes would later go onto shape much of North African history.

West Africa

[edit]

In the western Sahel the rise of settled communities occurred largely as a result of the domestication of millet and of sorghum. Archaeology points to sizable urban populations in West Africa beginning in the 4th millennium BC, which had crucially developed iron metallurgy by 1200 BC, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons.[101] Extensive east-west belts of deserts, grasslands, and forests from north to south were crucial for the moulding of their respective societies and meant that prior to the accession of trans-Saharan trade routes, symbiotic trade relations developed in response to the opportunities afforded by north–south diversity in ecosystems.[102] Various civilisations prospered in this period. From 4000 BC, the Tichitt culture in modern-day Mauritania and Mali was the oldest known complexly organised society in West Africa, with a four tiered hierarchical social structure.[103] Other civilisations include the Kintampo culture from 2500 BC in modern-day Ghana,[104] the Nok culture from 1500 BC in modern-day Nigeria,[105] the Daima culture around Lake Chad from 550 BC, Djenné-Djenno from 250 BC in modern-day Mali, and the Serer civilisation in modern-day Senegal, which built the Senegambian stone circles from the 3rd century BC. There is also detailed record[106] of Igodomigodo, a small kingdom founded presumably in 40 BC, which would later go on to form the Benin Empire.[107]

Towards the end of the 3rd century AD, a wet period in the Sahel created areas for human habitation and exploitation that had not been habitable for the best part of a millennium, with the Kingdom of Wagadu, the local name of the Ghana Empire, rising out of the Tichitt culture, growing wealthy following the introduction of the camel to the western Sahel, revolutionising the trans-Saharan trade that linked their capital and Aoudaghost with Tahert and Sijilmasa in North Africa.[108] Soninke traditions likely contain content from prehistory, mentioning four previous foundings of Wagadu, and holds that the final founding of Wagadu occurred after their first king did a deal with Bida, a serpent deity who was guarding a well, to sacrifice one maiden a year in exchange for assurance regarding plenty of rainfall and gold supply.[109] Wagadu's core traversed modern-day southern Mauritania and western Mali, and Soninke tradition portrays early Ghana as warlike, with horse-mounted warriors key to increasing its territory and population, although details of their expansion are extremely scarce.[108] Wagadu made its profits from maintaining a monopoly on gold heading north and salt heading south, despite not controlling the gold fields themselves, located in the forest regions.[110] It is probable that Wagadu's dominance on trade allowed for the gradual consolidation of many polities into a confederated state, whose composites stood in varying relations to the core, from fully administered to nominal tribute-paying parity.[111] Based on large tumuli scattered across West Africa dating to this period, it has been stipulated that relative to Wagadu, there were further simultaneous and preceding kingdoms that have unfortunately been lost to time.[112][103]

Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa

[edit]

1 = 2000–1500 BC origin

2 = c. 1500 BC first dispersal

2.a = Eastern Bantu

2.b = Western Bantu

3 = 1000–500 BC Urewe nucleus of Eastern Bantu

4–7 = southward advance

9 = 500–1 BC Congo nucleus

10 = AD 1–1000 last phase[113][114][115]

At the 4th millennium BC the Congo Basin was inhabited by the Bambenga, Bayaka, Bakoya, and Babongo in the west, the Bambuti in the east, and the Batwa who were widely scattered and also present in the Great Lakes region; together they are grouped as Pygmies.[116] On the later-named Swahili coast there were Cushitic-speaking peoples, and the Khoisan (a neologism for the Khoekhoe and San) in the continent's south.

The Bantu expansion constituted a major series of migrations of Bantu peoples from central Africa to eastern and southern Africa and was substantial in the settling of the continent.[117] Commencing in the 2nd millennium BC, the Bantu began to migrate from Cameroon to central, eastern, and southern Africa, laying the foundations for future states such as the Kingdom of Kongo in the Congo Basin, the Empire of Kitara in the African Great Lakes, the Luba Empire in the Upemba Depression, the Kilwa Sultanate in the Swahili coast by crowding out Azania, with Rhapta being its last stronghold by the 1st century AD.[118] These migrations also prefaced the Kingdom of Mapungubwe in the Zambezi basin. After reaching the Zambezi, the Bantu continued southward, with eastern groups continuing to modern-day Mozambique and reaching Maputo in the 2nd century AD. Further to the south, settlements of Bantu peoples who were iron-using agriculturists and herdsmen were well established south of the Limpopo River by the 4th century AD, displacing and absorbing the Khoisan.

By the Chari River south of Lake Chad the Sao civilisation flourished for over a millennium beginning in the 6th century BC, in territory that later became part of present-day Cameroon and Chad. Sao artifacts show that they were skilled workers in bronze, copper, and iron,[119]: 19 with finds including bronze sculptures, terracotta statues of human and animal figures, coins, funerary urns, household utensils, jewellery, highly decorated pottery, and spears.[119]: 19 [120]: 1051 Nearby, around Lake Ejagham in south-west Cameroon, the Ekoi civilisation rose circa 2nd century AD, and are most notable for constructing the Ikom monoliths and developing the Nsibidi script.[121]

9th to 18th centuries

[edit]

Pre-colonial Africa possessed as many as 10,000 different states and polities.[123] These included small family groups of hunter-gatherers such as the San people of southern Africa; larger, more structured groups such as the family clan groupings of the Bantu peoples of central, southern, and eastern Africa; heavily structured clan groups in the Horn of Africa; the large Sahelian kingdoms; and autonomous city-states and kingdoms, such as those of the Akan; Edo, Yoruba, and Igbo people in West Africa; and the Swahili coastal trading towns of Southeast Africa.

By the 9th century AD, a string of dynastic states, including the earliest Hausa states, stretched across the sub-Saharan savannah from the western regions to central Sudan. The most powerful of these states were Ghana, Gao, and the Kanem-Bornu Empire. Ghana declined in the eleventh century, but was succeeded by the Mali Empire, which consolidated much of western Sudan in the thirteenth century. Kanem accepted Islam in the eleventh century.

In the forested regions of the West African coast, independent kingdoms grew with little influence from the Muslim north. The Kingdom of Nri, which was ruled by the Eze Nri, was established around the ninth century, making it one of the oldest kingdoms in present-day Nigeri. The Nri kingdom is famous for its elaborate bronzes, found at the town of Igbo-Ukwu.[124]

The Kingdom of Ife, historically the first of these Yoruba city-states or kingdoms, established government under a priestly oba ('king' or 'ruler' in the Yoruba language), called the Ooni of Ife. Ife was noted as a major religious and cultural centre in West Africa and for its unique naturalistic tradition of bronze sculpture. The Ife model of government was adapted by the Oyo Empire, whose obas, called the Alaafins of Oyo, controlled many other Yoruba and non-Yoruba city-states and kingdoms including the Fon Kingdom of Dahomey.

The Almoravids were a Berber dynasty from the Sahara that spread over northwestern Africa and the Iberian peninsula during the eleventh century.[125] The Banu Hilal and Banu Ma'qil were a collection of Arab Bedouin tribes from the Arabian Peninsula who migrated westwards via Egypt between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries. Their migration resulted in the fusion of the Arabs and Berbers, where the locals were arabised,[126] and Arab culture absorbed elements of the local culture, under the unifying framework of Islam.[127]

Following the breakup of Mali, a local leader named Sonni Ali (1464–1492) founded the Songhai Empire in the region of middle Niger and the western Sudan and took control of the trans-Saharan trade. Sonni Ali seized Timbuktu in 1468 and Jenne in 1473, building his regime on trade revenues and the cooperation of Muslim merchants. His successor Askia Mohammad I (1493–1528) made Islam the official religion, built mosques, and brought to Gao Muslim scholars, including al-Maghili (d.1504), the founder of an important tradition of Sudanic African Muslim scholarship.[128] By the eleventh century, some Hausa states – such as Kano, Jigawa, Katsina, and Gobir – had developed into walled towns engaging in trade, servicing caravans, and the manufacture of goods. Until the fifteenth century, these small states were on the periphery of the major Sudanic empires of the era, paying tribute to Songhai to the west and Kanem-Borno to the east.

Height of the slave trade

[edit]

Slavery had long been practiced in Africa.[129][130] Between the 15th and the 19th centuries, the Atlantic slave trade took an estimated 7–12 million slaves to the New World.[131][132][133] In addition, more than 1 million Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates and sold as slaves in North Africa between the 16th and 19th centuries.[134]

In West Africa, the decline of the Atlantic slave trade in the 1820s caused dramatic economic shifts in local polities. The gradual decline of slave-trading, prompted by a lack of demand for slaves in the New World, increasing anti-slavery legislation in Europe and America, and the British Royal Navy's increasing presence off the West African coast, obliged African states to adopt new economies. Between 1808 and 1860, the British West Africa Squadron seized approximately 1,600 slave ships and freed 150,000 Africans who were aboard.[135]

Action was also taken against African leaders who refused to agree to British treaties to outlaw the trade, for example against "the usurping King of Lagos", deposed in 1851. Anti-slavery treaties were signed with over 50 African rulers.[136] The largest powers of West Africa (the Asante Confederacy, the Kingdom of Dahomey, and the Oyo Empire) adopted different ways of adapting to the shift. Asante and Dahomey concentrated on the development of "legitimate commerce" in the form of palm oil, cocoa, timber and gold, forming the bedrock of West Africa's modern export trade. The Oyo Empire, unable to adapt, collapsed into civil wars.[137]

Colonialism

[edit]The Scramble for Africa[e] was the invasion, conquest, and colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of "New Imperialism". Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom were the contending powers.

In 1870, 10% of the continent was formally under European control. By 1914, this figure had risen to almost 90%; the only states retaining sovereignty were Liberia, Ethiopia, Egba,[f] Aussa, Senusiyya,[139] Mbunda,[140] Ogaden/Haud,[141][142] the Dervish State, the Darfur Sultanate,[143] and the Ovambo kingdoms,[144][145] most of which were later conquered.

The 1884 Berlin Conference regulated European colonisation and trade in Africa, and is seen as emblematic of the "scramble".[146] In the last quarter of the 19th century, there were considerable political rivalries between the European empires, which provided the impetus for the colonisation.[147] The later years of the 19th century saw a transition from "informal imperialism" – military influence and economic dominance – to direct rule.[148][149]

With the decline of the European colonial empires in the wake of the two world wars, most African colonies gained independence during the Cold War, and decided to keep their colonial borders in the Organisation of African Unity conference of 1964 due to fears of civil wars and regional instability, placing emphasis on pan-Africanism.[150]Independence struggles

[edit]

Imperial rule by Europeans continued until after the conclusion of World War II, when almost all remaining colonial territories gradually obtained formal independence. Independence movements in Africa gained momentum following World War II, which left the major European powers weakened. In 1951, Libya, a former Italian colony, gained independence. In 1956, Tunisia and Morocco won their independence from France.[151] Ghana followed suit the next year (March 1957),[152] becoming the first of the sub-Saharan colonies to be granted independence. Over the next decade, waves of decolonisation took place across the continent, culminating in the 1960 Year of Africa and the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity in 1963.[33]

Portugal's overseas presence in sub-Saharan Africa (most notably in Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, and São Tomé and Príncipe) lasted from the 16th century to 1975, after the Estado Novo regime was overthrown in a military coup in Lisbon. Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence from the United Kingdom in 1965, under the white minority government of Ian Smith, but was not internationally recognised as an independent state (as Zimbabwe) until 1980, when black nationalists gained power after a bitter guerrilla war. Although South Africa was one of the first African countries to gain independence, the state remained under the control of the country's white minority, initially through qualified voting rights and from 1956 by a system of racial segregation known as apartheid, until 1994.

Post-colonial Africa

[edit]Today, Africa contains 54 sovereign countries.[citation needed] Since independence, African states have frequently been hampered by instability, corruption, violence, and authoritarianism. The vast majority of African states are republics that operate under some form of the presidential system of rule. However, few of them have been able to sustain democratic governments on a permanent basis—per the criteria laid out by Lührmann et al. (2018), only Botswana and Mauritius have been consistently democratic for the entirety of their post-colonial history. Most African countries have experienced several coups or periods of military dictatorship. Between 1990 and 2018, though, the continent as a whole has trended towards more democratic governance.[153]

Upon independence an overwhelming majority of Africans lived in extreme poverty. The continent suffered from the lack of infrastructural or industrial development under colonial rule, along with political instability. With limited financial resources or access to global markets, relatively stable countries such as Kenya still experienced only very slow economic development. Only a handful of African countries succeeded in obtaining rapid economic growth prior to 1990. Exceptions include Libya and Equatorial Guinea, both of which possess large oil reserves.

Instability throughout the continent after decolonisation resulted primarily from marginalisation of ethnic groups, and corruption. In pursuit of personal political gain, many leaders deliberately promoted ethnic conflicts, some of which had originated during the colonial period, such as from the grouping of multiple unrelated ethnic groups into a single colony, the splitting of a distinct ethnic group between multiple colonies, or existing conflicts being exacerbated by colonial rule (for instance, the preferential treatment given to ethnic Hutus over Tutsis in Rwanda during German and Belgian rule).

Faced with increasingly frequent and severe violence, military rule was widely accepted by the population of many countries as means to maintain order, and during the 1970s and 1980s a majority of African countries were controlled by military dictatorships. Territorial disputes between nations and rebellions by groups seeking independence were also common in independent African states. The most devastating of these was the Nigerian Civil War, fought between government forces and an Igbo separatist republic, which resulted in a famine that killed 1–2 million people. Two civil wars in Sudan, the first lasting from 1955 to 1972 and the second from 1983 to 2005, collectively killed around 3 million. Both were fought primarily on ethnic and religious lines.

Cold War conflicts between the United States and the Soviet Union also contributed to instability. Both the Soviet Union and the United States offered considerable incentives to African political and military leaders who aligned themselves with the superpowers' foreign policy. As an example, during the Angolan Civil War, the Soviet and Cuban aligned MPLA and the American aligned UNITA received the vast majority of their military and political support from these countries. Many African countries became highly dependent on foreign aid. The sudden loss of both Soviet and American aid at the end of the Cold War and fall of the USSR resulted in severe economic and political turmoil in the countries most dependent on foreign support.

There was a major famine in Ethiopia between 1983 and 1985, killing up to 1.2 million people, which most historians attribute primarily to the forced relocation of farmworkers and seizure of grain by the communist Derg government, further exacerbated by the civil war.[154][155][156][157] In 1994 a genocide in Rwanda resulted in up to 800,000 deaths, added to a severe refugee crisis and fueled the rise of militia groups in neighbouring countries. This contributed to the outbreak of the first and second Congo Wars, which were the most devastating military conflicts in modern Africa, with up to 5.5 million deaths,[158] making it by far the deadliest conflict in modern African history and one of the costliest wars in human history.[159]

-

An animated map shows the order of independence of African nations, 1950–2011.

-

Africa's wars and conflicts, 1980–96Major wars/conflicts (>100,000 casualties)Minor wars/conflictsOther conflicts

-

Political map of Africa in 2021

Various conflicts between various insurgent groups and governments continue. Since 2003, there has been an ongoing conflict in Darfur (Sudan), which peaked in intensity from 2003 to 2005 with notable spikes in violence in 2007 and 2013–15, killing around 300,000 people total. The Boko Haram Insurgency primarily within Nigeria (with considerable fighting in Niger, Chad, and Cameroon as well) has killed around 350,000 people since 2009. Most African conflicts have been reduced to low-intensity conflicts as of 2022. However, the Tigray War from 2020 to 2022 killed an estimated 300,000–500,000 people, primarily due to famine.

Overall though, violence across Africa has greatly declined in the 21st century, with the end of civil wars in Angola, Sierra Leone, and Algeria in 2002, Liberia in 2003, and Sudan and Burundi in 2005. The Second Congo War, which involved 9 countries and several insurgent groups, ended in 2003. This decline in violence coincided with many countries abandoning communist-style command economies and opening up for market reforms, which over the course of the 1990s and 2000s promoted the establishment of permanent, peaceful trade between neighbouring countries (see Capitalist peace).

Improved stability and economic reforms have led to a great increase in foreign investment into many African nations, mainly from China,[160] which further spurred economic growth. Between 2000 and 2014, annual GDP growth in sub-Saharan Africa averaged 5.02%, doubling its total GDP from $811 billion to $1.63 trillion (constant 2015 USD).[161] North Africa experienced comparable growth rates.[162] A significant part of this growth can also be attributed to the facilitated diffusion of information technologies and specifically the mobile telephone.[163] While several individual countries have maintained high growth rates, since 2014 overall growth has considerably slowed, primarily as a result of falling commodity prices, continued lack of industrialisation, and epidemics of Ebola and COVID-19.[164][165]

Geography

[edit]

Africa is the largest of the three great southward projections from the largest landmass of the Earth. Separated from Europe by the Mediterranean Sea, it is joined to Asia at its northeast extremity by the Isthmus of Suez (transected by the Suez Canal), 163 km (101 mi) wide.[166] Geopolitically, Egypt's Sinai Peninsula east of the Suez Canal is often considered part of Africa as well.[167]

The coastline is 26,000 km (16,000 mi) long, and the absence of deep indentations of the shore is illustrated by the fact that Europe, which covers only 10,400,000 km2 (4,000,000 sq mi) – about a third of the surface of Africa – has a coastline of 32,000 km (20,000 mi).[168] From the most northerly point, Ras ben Sakka in Tunisia (37°21' N), to the most southerly point, Cape Agulhas in South Africa (34°51'15" S), is a distance of approximately 8,000 km (5,000 mi).[169] Cape Verde, 17°33'22" W, the westernmost point, is a distance of approximately 7,400 km (4,600 mi) to Ras Hafun, 51°27'52" E, the most easterly projection that neighbours Cape Guardafui, the tip of the Horn of Africa.[168]

Africa's largest country is Algeria, and its smallest country is Seychelles, an archipelago off the east coast.[170] The smallest nation on the continental mainland is The Gambia.

African plate

[edit]

The African plate, also known as the Nubian plate, is a major tectonic plate that includes most of the continent of Africa (except for its easternmost part) and the adjacent oceanic crust to the west and south. It also includes a narrow strip of Western Asia along the Mediterranean Sea, including much of Israel and Lebanon. It is bounded by the North American plate and South American plate to the west (separated by the Mid-Atlantic Ridge); the Arabian plate and Somali plate to the east; the Eurasian plate, Aegean Sea plate and Anatolian plate to the north; and the Antarctic plate to the south.

Between 60 million years ago and 10 million years ago, the Somali plate began rifting from the African plate along the East African Rift.[171] Since the continent of Africa consists of crust from both the African and the Somali plates, some literature refers to the African plate as the Nubian plate to distinguish it from the continent as a whole.[172]Climate

[edit]The climate of Africa ranges from tropical to subarctic on its highest peaks. Its northern half is primarily desert, or arid, while its central and southern areas contain both savanna plains and dense jungle (rainforest) regions. In between, there is a convergence, where vegetation patterns such as sahel and steppe dominate. Africa is the hottest continent on Earth and 60% of the entire land surface consists of drylands and deserts.[173] The record for the highest-ever recorded temperature, in Libya in 1922 (58 °C (136 °F)), was discredited in 2013.[174][175]

Climate change

[edit]

Climate change in Africa is a serious threat as Africa is one of the most vulnerable regions to the effects of climate change, despite contributing the least to causing it. Climate change is causing increasingly erratic rainfall patterns, more frequent extreme weather events including droughts, floods, and rising sea surface temperatures in Africa. These changes threaten food and water security, biodiversity, public health, and economic development.[176][177] Africa is currently warming faster than the rest of the world on average.[178]

Climate change intensifies existing socioeconomic vulnerabilities. Large segments of the African population depend on climate-sensitive livelihoods such as agriculture (55 - 62% of the workforce in sub-Saharan Africa)[179] and already live in poverty, heightening their exposure to shocks. Health outcomes worsen as heat stress, vector-borne diseases (such as malaria and dengue), and malnutrition become more prevalent. Over half (56%) of the over 2,000 recorded public health incidents in Africa between 2001 and 2021 were connected to climate change.[180] Resource scarcity contributes to displacement and conflict, particularly in fragile regions. Urban areas, often characterized by informal settlements, face heightened risks from flooding and extreme heat.[176]Ecology and biodiversity

[edit]

Africa has over 3,000 protected areas, with 198 marine protected areas, 50 biosphere reserves, and 80 wetlands reserves. Significant habitat destruction, increases in human population and poaching are reducing Africa's biological diversity and arable land. Human encroachment, civil unrest and the introduction of non-native species threaten biodiversity in Africa. This has been exacerbated by administrative problems, inadequate personnel and funding problems.[173]

Deforestation is affecting Africa at twice the world rate, according to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).[181] According to the University of Pennsylvania African Studies Center, 31% of Africa's pasture lands and 19% of its forests and woodlands are classified as degraded, and Africa is losing over four million hectares of forest per year, which is twice the average deforestation rate for the rest of the world.[173] Some sources claim that approximately 90% of the original, virgin forests in West Africa have been destroyed.[182] Over 90% of Madagascar's original forests have been destroyed since the arrival of humans 2000 years ago.[183] About 65% of Africa's agricultural land suffers from soil degradation.[184]

Fauna

[edit]

Africa boasts perhaps the world's largest combination of density and "range of freedom" of wild animal populations and diversity, with wild populations of large carnivores (such as lions, hyenas, and cheetahs) and herbivores (such as buffalo, elephants, camels, and giraffes) ranging freely on primarily open non-private plains. It is also home to a variety of "jungle" animals including snakes and primates and aquatic life such as crocodiles and amphibians. In addition, Africa has the largest number of megafauna species, as it was least affected by the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna.

Environmental issues

[edit]Politics

[edit]African Union

[edit]

Northern Region , Southern Region , Eastern Region , Western Regions A and B , Central Region

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of 55 member states. The union was formed, with Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, as its headquarters, on 26 June 2001. The union was officially established on 9 July 2002[187] as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). In July 2004, the African Union's Pan-African Parliament (PAP) was relocated to Midrand, in South Africa, but the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights remained in Addis Ababa.

The African Union, not to be confused with the AU Commission, is formed by the Constitutive Act of the African Union, which aims to transform the African Economic Community, a federated commonwealth, into a state under established international conventions. The African Union has a parliamentary government, known as the African Union Government, consisting of legislative, judicial and executive organs. It is led by the African Union President and Head of State, who is also the President of the Pan-African Parliament. A person becomes AU President by being elected to the PAP, and subsequently gaining majority support in the PAP. The powers and authority of the President of the African Parliament derive from the Constitutive Act and the Protocol of the Pan-African Parliament, as well as the inheritance of presidential authority stipulated by African treaties and by international treaties, including those subordinating the Secretary General of the OAU Secretariat (AU Commission) to the PAP. The government of the AU consists of all-union, regional, state, and municipal authorities, as well as hundreds of institutions, that together manage the day-to-day affairs of the institution.

Extensive human rights abuses still occur in several parts of Africa, often under the oversight of the state. Most of such violations occur for political reasons, often as a side effect of civil war. Countries where major human rights violations have been reported in recent times include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Sudan, Zimbabwe, and Ivory Coast.

Boundary conflicts

[edit]List of states and territories

[edit]The countries in this table are categorised according to the scheme for geographic subregions used by the United Nations, and data included are per sources in cross-referenced articles. Where they differ, provisos are clearly indicated.

| Arms | Flag | Name of region[g] and territory, with flag |

Area (km2) |

Population[192] | Year | Density (per km2) |

Capital | Name(s) in official language(s) | ISO 3166-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Africa | |||||||||

| Algeria | 2,381,740 | 46,731,000 | 2022 | 17.7 | Algiers | الجزائر (al-Jazāʾir)/Algérie | DZA | ||

| Egypt[h] | 1,001,450 | 82,868,000 | 2012 | 83 | Cairo | مِصر (Miṣr) | EGY | ||

| Libya | 1,759,540 | 6,310,434 | 2009 | 4 | Tripoli | ليبيا (Lībiyā) | LBY | ||

| Morocco | 446,550 | 35,740,000 | 2017 | 78 | Rabat | المغرب (al-maḡrib)/ⵍⵎⵖⵔⵉⴱ (lmeɣrib)/Maroc | MAR | ||

| Sudan | 1,861,484 | 30,894,000 | 2008 | 17 | Khartoum | Sudan/السودان (as-Sūdān) | SDN | ||

| Tunisia | 163,610 | 10,486,339 | 2009 | 64 | Tunis | تونس (Tūnis)/Tunest/Tunisie | TUN | ||

| Western Sahara[i] | 266,000 | 405,210 | 2009 | 2 | El Aaiún | الصحراء الغربية (aṣ-Ṣaḥrā' al-Gharbiyyah)/Taneẓroft Tutrimt/Sáhara Occidental | ESH | ||

| East Africa | |||||||||

| Burundi | 27,830 | 8,988,091 | 2009 | 323 | Gitega | Uburundi/Burundi/Burundi | BDI | ||

| Comoros | 2,170 | 752,438 | 2009 | 347 | Moroni | Komori/Comores/جزر القمر (Juzur al-Qumur) | COM | ||

| Djibouti | 23,000 | 828,324 | 2015 | 22 | Djibouti | Yibuuti/جيبوتي (Jībūtī)/Djibouti/Jabuuti | DJI | ||

| Eritrea | 121,320 | 5,647,168 | 2009 | 47 | Asmara | Eritrea | ERI | ||

| Ethiopia | 1,127,127 | 84,320,987 | 2012 | 75 | Addis Ababa | ኢትዮጵያ (Ītyōṗṗyā)/Itiyoophiyaa/ኢትዮጵያ/Itoophiyaa/Itoobiya/ኢትዮጵያ | ETH | ||

| French Southern Territories (France) | 439,781 | 100 | 2019 | — | Saint Pierre | Terres australes et antarctiques françaises | FRA-TF | ||

| Kenya | 582,650 | 39,002,772 | 2009 | 66 | Nairobi | Kenya | KEN | ||

| Madagascar | 587,040 | 20,653,556 | 2009 | 35 | Antananarivo | Madagasikara/Madagascar | MDG | ||

| Malawi | 118,480 | 14,268,711 | 2009 | 120 | Lilongwe | Malaŵi/Malaŵi | MWI | ||

| Mauritius | 2,040 | 1,284,264 | 2009 | 630 | Port Louis | Mauritius/Maurice/Moris | MUS | ||

| Mayotte (France) | 374 | 223,765 | 2009 | 490 | Mamoudzou | Mayotte/Maore/Maiôty | MYT | ||

| Mozambique | 801,590 | 21,669,278 | 2009 | 27 | Maputo | Moçambique/Mozambiki/Msumbiji/Muzambhiki | MOZ | ||

| Réunion (France) | 2,512 | 743,981 | 2002 | 296 | Saint Denis | La Réunion | FRA-RE | ||

| Rwanda | 26,338 | 10,473,282 | 2009 | 398 | Kigali | Rwanda | RWA | ||

| Seychelles | 455 | 87,476 | 2009 | 192 | Victoria | Seychelles/Sesel | SYC | ||

| Somalia | 637,657 | 9,832,017 | 2009 | 15 | Mogadishu | 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖 (Soomaaliya) /الصومال (aṣ-Ṣūmāl) | SOM | ||

| Somaliland | 176,120 | 5,708,180 | 2021 | 25 | Hargeisa | Soomaaliland/صوماليلاند (Ṣūmālīlānd) | |||

| South Sudan | 619,745 | 8,260,490 | 2008 | 13 | Juba | South Sudan | SSD | ||

| Tanzania | 945,087 | 44,929,002 | 2009 | 43 | Dodoma | Tanzania/Tanzania | TZA | ||

| Uganda | 236,040 | 32,369,558 | 2009 | 137 | Kampala | Uganda/Yuganda | UGA | ||

| Zambia | 752,614 | 11,862,740 | 2009 | 16 | Lusaka | Zambia | ZMB | ||

| Zimbabwe | 390,580 | 11,392,629 | 2009 | 29 | Harare | Zimbabwe | ZWE | ||

| Central Africa | |||||||||

| Angola | 1,246,700 | 12,799,293 | 2009 | 10 | Luanda | Angola | AGO | ||

| Cameroon | 475,440 | 18,879,301 | 2009 | 40 | Yaoundé | Cameroun/Kamerun | CMR | ||

| Central African Republic | 622,984 | 4,511,488 | 2009 | 7 | Bangui | Ködörösêse tî Bêafrîka/République centrafricaine | CAF | ||

| Chad | 1,284,000 | 10,329,208 | 2009 | 8 | N'Djamena | تشاد (Tšād)/Tchad | TCD | ||

| Republic of the Congo | 342,000 | 4,012,809 | 2009 | 12 | Brazzaville | Congo/Kôngo/Kongó | COG | ||

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2,345,410 | 69,575,000 | 2012 | 30 | Kinshasa | République démocratique du Congo | COD | ||

| Equatorial Guinea | 28,051 | 633,441 | 2009 | 23 | Malabo | Guinea Ecuatorial/Guinée Équatoriale/Guiné Equatorial | GNQ | ||

| Gabon | 267,667 | 1,514,993 | 2009 | 6 | Libreville | Gabon | GAB | ||

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 1,001 | 212,679 | 2009 | 212 | São Tomé | São Tomé e Príncipe | STP | ||

| Southern Africa | |||||||||

| Botswana | 600,370 | 1,990,876 | 2009 | 3 | Gaborone | Botswana/Botswana | BWA | ||

| Eswatini | 17,363 | 1,123,913 | 2009 | 65 | Mbabane | eSwatini/Eswatini | SWZ | ||

| Lesotho | 30,355 | 2,130,819 | 2009 | 70 | Maseru | Lesotho/Lesotho | LSO | ||

| Namibia | 825,418 | 2,108,665 | 2009 | 3 | Windhoek | Namibia | NAM | ||

| South Africa | 1,219,912 | 51,770,560 | 2011 | 42 | Bloemfontein, Cape Town, Pretoria[j] | yaseNingizimu Afrika/yoMzantsi-Afrika/Suid-Afrika/Afrika-Borwa/Aforika Borwa/Afrika Borwa/Afrika Dzonga/yeNingizimu Afrika/Afurika Tshipembe/yeSewula Afrika | ZAF | ||

| West Africa | |||||||||

| Benin | 112,620 | 8,791,832 | 2009 | 78 | Porto-Novo | Bénin | BEN | ||

| Burkina Faso | 274,200 | 15,746,232 | 2009 | 57 | Ouagadougou | Burkina Faso | BFA | ||

| Cape Verde | 4,033 | 429,474 | 2009 | 107 | Praia | Cabo Verde/Kabu Verdi | CPV | ||

| The Gambia | 11,300 | 1,782,893 | 2009 | 158 | Banjul | The Gambia | GMB | ||

| Ghana | 239,460 | 23,832,495 | 2009 | 100 | Accra | Ghana | GHA | ||

| Guinea | 245,857 | 10,057,975 | 2009 | 41 | Conakry | Guinée | GIN | ||

| Guinea-Bissau | 36,120 | 1,533,964 | 2009 | 43 | Bissau | Guiné-Bissau | GNB | ||

| Ivory Coast | 322,460 | 20,617,068 | 2009 | 64 | Abidjan,[k] Yamoussoukro | Côte d'Ivoire | CIV | ||

| Liberia | 111,370 | 3,441,790 | 2009 | 31 | Monrovia | Liberia | LBR | ||

| Mali | 1,240,000 | 12,666,987 | 2009 | 10 | Bamako | Mali/Maali/مالي (Mālī)/𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Maali)/ߡߊߟߌ (Mali) | MLI | ||

| Mauritania | 1,030,700 | 3,129,486 | 2009 | 3 | Nouakchott | موريتانيا (Mūrītānyā) | MRT | ||

| Niger | 1,267,000 | 15,306,252 | 2009 | 12 | Niamey | Niger | NER | ||

| Nigeria | 923,768 | 166,629,000 | 2012 | 180 | Abuja | Nigeria | NGA | ||

| Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha (United Kingdom) | 420 | 7,728 | 2012 | 13 | Jamestown | Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha | SHN | ||

| Senegal | 196,190 | 13,711,597 | 2009 | 70 | Dakar | Sénégal | SEN | ||

| Sierra Leone | 71,740 | 6,440,053 | 2009 | 90 | Freetown | Sierra Leone | SLE | ||

| Togo | 56,785 | 6,019,877 | 2009 | 106 | Lomé | Togo | TGO | ||

| Africa Total | 30,368,609 | 1,001,320,281 | 2009 | 33 | |||||

Other territories

[edit]This list contains nine territories that are administered as incorporated areas of a primarily non-African country but that belong geographically to the African continent.

| Flag | Map | English short, formal names, and ISO | Ruling power | Status[citation needed] | Domestic short name(s) and formal name(s) |

Capital | Population | Area[citation needed] | Currency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Canary Islands Autonomous Region of the Canary Islands ES-CN |

Autonomous community of Spain | Spanish: Islas Canarias | Santa Cruz and Las Palmas[193] Spanish: Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria |

2,207,225 | 7,447 km2 (2,875 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Ceuta Autonomous City of Ceuta ES-CE |

Autonomous city of Spain | Spanish: Ceuta—Ciudad autónoma de Ceuta | Ceuta Spanish: Ceuta |

84,843 | 28 km2 (11 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Madeira Autonomous Region of Madeira PT-30 |

Autonomous Region of Portugal | Portuguese: Madeira—Região Autónoma da Madeira | Funchal Portuguese: Funchal |

267,785 | 828 km2 (320 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Mayotte Mayotte Region YT |

Overseas region and constituent part of the French Republic | French: Mayotte—Région Mayotte | Mamoudzou French: Mamoudzou |

266,380 | 374 km2 (144 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Melilla Autonomous City of Melilla ES-ML |

Autonomous city of Spain | Spanish: Melilla—Ciudad autónoma de Melilla | Melilla Spanish: Melilla |

84,714 | 20 km2 (8 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Pelagie Islands |

Archipelago of Italy | Italian: Isole Pelagie Sicilian: Ìsuli Pilaggî |

Lampedusa e Linosa[l] Italian: Lampedusa e Linosa Sicilian: Lampidusa e Linusa[194] |

6,304 | 21.4 km2 (8 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Plazas de soberanía |

Overseas territory of Spain | Spanish: Plazas de soberanía | N/A | 74 | 0.59 km2 (0.23 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Réunion Réunion Region RE |

Overseas region and constituent part of the French Republic | French: Réunion—Région Réunion | Saint-Denis French: Saint-Denis |

889,918 | 2,512 km2 (970 sq mi) | euro | |

|

|

Socotra Archipelago |

Governorate of Yemen | Arabic: أرخبيل سقطرى (ʾArḫabīl Suquṭrā) |

Hadibu Arabic: اديبو (Ḥādībū) |

60,550 | 3,974.64 km2 (1,535 sq mi) | Yemeni rial |

Economy

[edit]

Although it has abundant natural resources, Africa remains the world's poorest and least-developed continent (other than Antarctica), the result of a variety of causes that may include corrupt governments that have often committed serious human rights violations, failed central planning, high levels of illiteracy, low self-esteem, lack of access to foreign capital, legacies of colonialism, the slave trade, the Cold War, and frequent tribal and military conflict (ranging from guerrilla warfare to genocide).[195] Its total nominal GDP remains behind that of the United States, China, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, India and France. According to the United Nations' Human Development Report in 2003, the bottom 24 ranked nations (151st to 175th) were all African.[196]

Poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition, inadequate water supply and sanitation, and poor health affect a large proportion of the people who reside on the African continent. In August 2008, the World Bank[197] announced revised global poverty estimates based on a new international poverty line of $1.25 per day (versus the previous measure of $1.00). Eighty-one percent of the sub-Saharan African population was living on less than $2.50 (PPP) per day in 2005, compared with 86% for India.[198]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the least successful region of the world in reducing poverty ($1.25 per day); some 50% of the population living in poverty in 1981 (200 million people), a figure that rose to 58% in 1996 before dropping to 50% in 2005 (380 million people). The average poor person in sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to live on only 70 cents per day, and was poorer in 2003 than in 1973,[199] indicating increasing poverty in some areas. Some of it is attributed to unsuccessful economic liberalisation programmes spearheaded by foreign companies and governments, but other studies have cited bad domestic government policies more than external factors.[200][201]

Africa is now at risk of being in debt once again, particularly in sub-Saharan African countries. The last debt crisis in 2005 was resolved with help from the heavily indebted poor countries scheme (HIPC). The HIPC resulted in some positive and negative effects on the economy in Africa. About ten years after the 2005 debt crisis in sub-Saharan Africa was resolved, Zambia fell back into debt. A small reason was due to the fall in copper prices in 2011, but the bigger reason was that a large amount of the money Zambia borrowed was wasted or pocketed by the elite.[202]

From 1995 to 2005, Africa's rate of economic growth increased, averaging 5% in 2005. Some countries experienced still higher growth rates, notably Angola, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea, all of which had recently begun extracting their petroleum reserves or had expanded their oil extraction capacity.

In a recently published analysis based on World Values Survey data, the Austrian political scientist Arno Tausch maintained that several African countries, most notably Ghana, perform quite well on scales of mass support for democracy and the market economy.[203]

The following table shows the projected nominal GDP and GDP per capita (at Purchasing Power Parity) in 2025 by the IMF.[204]

| Rank | Country | GDP (nominal, in 2025) millions of USD |

GDP per capita (PPP, in 2025) in international dollars |

|---|---|---|---|

| — | 2,834,002 | 7,373 | |

| 1 | 410,338 | 15,989 | |

| 2 | 347,342 | 21,668 | |

| 3 | 268,885 | 18,525 | |

| 4 | 188,271 | 6,792 | |

| 5 | 165,835 | 11,266 | |

| 6 | 131,673 | 7,534 | |

| 7 | 117,457 | 4,398 | |

| 8 | 113,343 | 10,234 | |

| 9 | 94,483 | 8,111 | |

| 10 | 88,332 | 8,417 | |

| 11 | 85,977 | 4,371 | |

| 12 | 79,119 | 1,884 | |

| 13 | 64,277 | 3,896 | |

| 14 | 56,291 | 14,779 | |

| 15 | 56,011 | 5,760 |

Tausch's global value comparison based on the World Values Survey derived the following factor analytical scales: 1. The non-violent and law-abiding society 2. Democracy movement 3. Climate of personal non-violence 4. Trust in institutions 5. Happiness, good health 6. No redistributive religious fundamentalism 7. Accepting the market 8. Feminism 9. Involvement in politics 10. Optimism and engagement 11. No welfare mentality, acceptancy of the Calvinist work ethics. The spread in the performance of African countries with complete data, Tausch concluded "is really amazing". While one should be especially hopeful about the development of future democracy and the market economy in Ghana, the article suggests pessimistic tendencies for Egypt and Algeria, and especially for Africa's leading economy, South Africa. High human inequality, as measured by the UNDP's Human Development Report's Index of Human Inequality, impairs the development of human security. Tausch also maintains that the certain recent optimism, corresponding to economic and human rights data, emerging from Africa, is reflected in the development of a civil society.

The continent is believed to hold 90% of the world's cobalt, 90% of its platinum, 50% of its gold, 98% of its chromium, 70% of its tantalite,[205] 64% of its manganese and one-third of its uranium.[206] The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has 70% of the world's coltan, a mineral used in the production of tantalum capacitors for electronic devices such as cell phones. The DRC also has more than 30% of the world's diamond reserves.[207] Guinea is the world's largest exporter of bauxite.[208] As the growth in Africa has been driven mainly by services and not manufacturing or agriculture, it has been growth without jobs and without reduction in poverty levels. In fact, the food security crisis of 2008, which took place on the heels of the global financial crisis, pushed 100 million people into food insecurity.[209]

In recent years, China has built increasingly stronger ties with African nations and is Africa's largest trading partner. In 2007, Chinese companies invested a total of US$1 billion in Africa.[160]

A Harvard University study led by professor Calestous Juma showed that Africa could feed itself by making the transition from importer to self-sufficiency. "African agriculture is at the crossroads; we have come to the end of a century of policies that favoured Africa's export of raw materials and importation of food. Africa is starting to focus on agricultural innovation as its new engine for regional trade and prosperity."[210]

Electricity generation

[edit]The main source of electricity is hydropower, which contributes significantly to the current installed capacity for energy.[211] The Kainji Dam is a typical hydropower resource generating electricity for all the large cities in Nigeria as well as their neighbouring country, Niger.[212] Hence, the continuous investment in the last decade, which has increased the amount of power generated.[211]

Infrastructure

[edit]Water resources

[edit]Water development and management are complex in Africa due to the multiplicity of trans-boundary water resources (rivers, lakes and aquifers).[211] Around 75% of sub-Saharan Africa falls within 53 international river basin catchments that traverse multiple borders.[213][211] This particular constraint can also be converted into an opportunity if the potential for trans-boundary cooperation is harnessed in the development of the area's water resources.[211] A multi-sectoral analysis of the Zambezi River, for example, shows that riparian cooperation could lead to a 23% increase in firm energy production without any additional investments.[213][211] A number of institutional and legal frameworks for transboundary cooperation exist, such as the Zambezi River Authority, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol, Volta River Authority and the Nile Basin Commission.[211] However, additional efforts are required to further develop political will, as well as the financial capacities and institutional frameworks needed for win-win multilateral cooperative actions and optimal solutions for all riparians.[211]

Demographics

[edit]- Nigeria (15.4%)

- Ethiopia (8.37%)

- Egypt (7.65%)

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (6.57%)

- Tanzania (4.55%)

- South Africa (4.47%)

- Kenya (3.88%)

- Uganda (3.38%)

- Algeria (3.36%)

- Other (42.4%)

Africa is considered by anthropologists to be the most genetically diverse continent as a result of being the longest inhabited.[214][215][216] Africa's population has rapidly increased over the last 40 years, and is consequently relatively young. In some African states, more than half the population is under 25 years of age.[217] The total number of people in Africa increased from 229 million in 1950 to 630 million in 1990.[218] As of 2021, the population of Africa is estimated at 1.4 billion.[1][2] Africa's total population surpassing other continents is fairly recent; African population surpassed Europe in the 1990s, while the Americas was overtaken sometime around the year 2000.[219] This increase in number of babies born in Africa compared to the rest of the world is expected to reach approximately 37% in the year 2050; while in 1990 sub-Saharan Africa accounted for only 16% of the world's births.[220]

The total fertility rate (children per woman) for Sub-Saharan Africa is 4.7 as of 2018, the highest in the world.[221] All countries in sub-Saharan Africa had TFRs (average number of children) above replacement level in 2019 and accounted for 27.1% of global livebirths.[222] In 2021, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 29% of global births.[223]

Speakers of Bantu languages (part of the Niger–Congo family) are the majority in southern, central and southeast Africa. The Bantu-speaking peoples from the Sahel progressively expanded over most of sub-Saharan Africa.[224] But there are also several Nilotic groups in South Sudan and East Africa, the mixed Swahili people on the Swahili Coast, and a few remaining indigenous Khoisan ("San" or "Bushmen") and Pygmy peoples in Southern and Central Africa, respectively. Bantu-speaking Africans also predominate in Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, and are found in parts of southern Cameroon. In the Kalahari Desert of Southern Africa, the distinct people known as the Bushmen (also "San", closely related to, but distinct from "Hottentots") have long been present. The San are physically distinct from other Africans and are the indigenous people of southern Africa.[citation needed] Pygmies are the pre-Bantu indigenous peoples of central Africa.[225]

The peoples of West Africa primarily speak Niger–Congo languages, belonging mostly to its non-Bantu branches, though some Nilo-Saharan and Afro-Asiatic speaking groups are also found. The Niger–Congo-speaking Yoruba, Igbo, Fulani, Akan, and Wolof ethnic groups are the largest and most influential. In the central Sahara, Mandinka or Mande groups are most significant. Chadic-speaking groups, including the Hausa, are found in more northerly parts of the region nearest to the Sahara, and Nilo-Saharan communities, such as the Songhai, Kanuri and Zarma, are found in the eastern parts of West Africa bordering Central Africa.

| Map of Africa indicating Human Development Index (2018). | ||

|

The peoples of North Africa consist of three main indigenous groups: Berbers in the northwest, Egyptians in the northeast, and Nilo-Saharan-speaking peoples in the east. The Arabs who arrived in the 7th century AD introduced the Arabic language and Islam to North Africa. The Semitic Phoenicians (who founded Carthage) and Hyksos, the Indo-Iranian Alans, the Indo-European Greeks, Romans, and Vandals settled in North Africa as well. Significant Berber communities remain within Morocco and Algeria in the 21st century, while, to a lesser extent, Berber speakers are also present in some regions of Tunisia and Libya.[226] The Berber-speaking Tuareg and other often-nomadic peoples are the principal inhabitants of the Saharan interior of North Africa. In Mauritania, there is a small but near-extinct Berber community in the north and Niger–Congo-speaking peoples in the south, though in both regions Arabic and Arab culture predominates. In Sudan, although Arabic and Arab culture predominate, it is mostly inhabited by groups that originally spoke Nilo-Saharan, such as the Nubians, Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa, who, over the centuries, have variously intermixed with migrants from the Arabian peninsula. Small communities of Afro-Asiatic-speaking Beja nomads can also be found in Egypt and Sudan.[227]

In the Horn of Africa, some Ethiopian and Eritrean groups (like the Amhara and Tigrayans, collectively known as Habesha) speak languages from the Semitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, while the Oromo and Somali speak languages from the Cushitic branch of Afro-Asiatic.

Prior to the decolonisation movements of the post-World War II era, Europeans were represented in every part of Africa.[228] Decolonization during the 1960s and 1970s often resulted in the mass emigration of white settlers—especially from Algeria and Morocco (1.6 million pieds-noirs in North Africa),[229] Kenya, Congo,[230] Rhodesia, Mozambique and Angola.[231] Between 1975 and 1977, over a million colonials returned to Portugal alone.[232] Nevertheless, white Africans remain an important minority in many African states, particularly Zimbabwe, Namibia, Réunion, and South Africa.[233] The country with the largest white African population is South Africa.[234] Dutch and British diasporas represent the largest communities of European ancestry on the continent today.[235]

European colonisation also brought sizable groups of Asians, particularly from the Indian subcontinent, to British colonies. Large Indian communities are found in South Africa, and smaller ones are present in Kenya, Tanzania, and some other southern and southeast African countries. The large Indian community in Uganda was expelled by the dictator Idi Amin in 1972, though many have since returned. The islands in the Indian Ocean are also populated primarily by people of Asian origin, often mixed with Africans and Europeans. The Malagasy people of Madagascar are an Austronesian people, but those along the coast are generally mixed with Bantu, Arab, Indian and European origins. Malay and Indian ancestries are also important components in the group of people known in South Africa as Cape Coloureds (people with origins in two or more races and continents). During the 20th century, small but economically important communities of Lebanese[160] have also developed in the larger coastal cities of West and East Africa, respectively.[236]

Alternative estimates of African population, 1–2018 AD (in thousands)

[edit]Source: Maddison and others (University of Groningen)[237]

| Year[237] | 1 | 1000 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | 1820 | 1870 | 1913 | 1950 | 1973 | 1998 | 2018 | 2100 (projected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 16 500 | 33 000 | 46 000 | 55 000 | 61 000 | 74 208 | 90 466 | 124 697 | 228 342 | 387 645 | 759 954 | 1 321 000[238] | 3 924 421[239] |

| World | 230 820 | 268 273 | 437 818 | 555 828 | 603 410 | 1 041 092 | 1 270 014 | 1 791 020 | 2 524 531 | 3 913 482 | 5 907 680 | 7 500 000[240] | 10 349 323[239] |

Shares of Africa and world population, 1–2020 AD (% of world total)

[edit]Source: Maddison and others (University of Groningen)[237]

| Year[237] | 1 | 1000 | 1500 | 1600 | 1700 | 1820 | 1870 | 1913 | 1950 | 1973 | 1998 | 2020 | 2100 (projected) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 7.1 | 12.3 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 12.9 | 18.2[238] | 39.4[241] |

Religion

[edit]