Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ampara

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

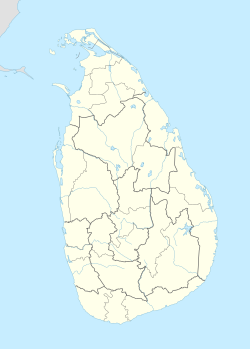

Ampara (Sinhala: අම්පාර, Tamil: அம்பாறை) is the main town of Ampara District, governed by an Urban Council.

Key Information

It is located in the Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, about 360 km (224 mi) east of Colombo and approximately 60 km (37 mi) south of Batticaloa.

History

[edit]This was a hunters' resting place during British colonial days (late 1890s and early 1900). During the development of the Gal Oya scheme from 1949 by the Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake, Ampara was transformed into a town.[2] Initially it was the residence for the construction workers of Inginiyagala Dam. Later it became the main administrative town of the Gal Oya Valley.

Religious composition in Ampara DS Division according to 2012 census data is as follows Buddhists 42,584-97.16%, Roman Catholics 537-1.23%, Islam 322-0.73%, Other Christian 237-0.54%, Hindus 145-0.33%, Others 4-0.01%.

References

[edit]- ^ "Statistical Information". Ampara District Secretriat. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 September 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Statistical Pocket Book of the Republic of Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Department of Census and Statistics. 1977. p. 137.

Ampara

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

Ampara District occupies the southeastern portion of Sri Lanka in the Eastern Province. It borders Polonnaruwa and Batticaloa districts to the north, the Indian Ocean to the east, Hambantota District to the south, and Monaragala, Badulla, and Matale districts to the west.[6] The district encompasses an area of approximately 4,495 square kilometers.[6] The administrative town of Ampara is positioned at coordinates 7°17′ N latitude and 81°40′ E longitude, with an average elevation of 45 meters above sea level.[7][8] The district's topography ranges from flat coastal plains to undulating inland terrain, with elevations from sea level up to 500 meters and isolated erosional remnants reaching 700 meters.[6] Physical features include eastern coastal plains fringed by the Indian Ocean, adjacent lagoons, and dry zone interiors marked by low-relief landscapes, inselbergs, and patches of dry evergreen forests.[9] Kumana National Park, located in the southeastern part of the district, exemplifies these natural elements with its wetland and forested habitats.[10]Climate and Environment

Ampara District exhibits a tropical monsoon climate typical of Sri Lanka's eastern dry and intermediate zones, with consistently warm temperatures and distinct seasonal rainfall patterns driven by monsoon winds. Average daily temperatures range from 27°C to 31°C annually, with highs often reaching 31–33°C and lows around 25–26°C, showing minimal fluctuation throughout the year due to the equatorial proximity.[11][12] Precipitation totals average 1,300–1,700 mm per year, concentrated during the northeast monsoon from October to February, which delivers the bulk of rainfall—up to 220–270 mm monthly in November and December—while the southwest monsoon from May to July contributes lesser amounts to coastal areas. Drier inter-monsoon periods from March to April and August to September see reduced totals, often below 50–70 mm monthly, heightening drought risks in inland regions.[11][10][13] Environmental conditions are shaped by the Indian Ocean's influence, promoting coastal biodiversity in mangroves, lagoons, and wetlands that harbor species such as migratory birds and marine life, though these ecosystems face erosion and salinization. Occasional cyclones, like those forming in the Bay of Bengal, pose threats of storm surges, while the 2004 tsunami inflicted widespread coastal habitat destruction in Ampara, eroding beaches and damaging reefs. Recent droughts, including severe episodes in 2017 and 2023, have intensified water scarcity and land degradation, underscoring the district's vulnerability to rainfall variability.[9][14][15][16]Demographics

Population and Growth

The Ampara District had a population of 649,402 according to Sri Lanka's 2012 Census of Population and Housing.[17] This figure marked an increase from 592,997 in the 2001 census, yielding an annual growth rate of 0.85% over the intercensal period.[18] The district spans 4,415 square kilometers, resulting in a population density of 147.1 persons per square kilometer in 2012.[18] Ampara town, serving as the district's administrative center and governed by the Ampara Urban Council, recorded 22,511 residents in the 2012 census.[17] This urban population constituted approximately 3.5% of the district total, highlighting the area's predominantly rural composition with limited urbanization.[19] Density in the urban council area reached higher levels than the district average, supporting its role in drawing administrative and service-related migration.[20] Provisional data from the 2024 census estimate the district population at 744,150, implying an annual growth rate of 1.1% from 2012 onward, exceeding the national average of 0.5% for the same period.[21][22] These trends reflect steady expansion, with urban-rural distributions maintaining the district's low overall density of around 169 persons per square kilometer by 2024.Ethnic and Religious Composition

Ampara District exhibits a diverse ethnic composition, with Sri Lankan Moors forming the largest group at 43.4% of the population (281,702 individuals), followed by Sinhalese at 38.9% (252,458), and Sri Lankan Tamils at 17.3% (112,457), alongside smaller numbers of Indian Tamils and other minorities totaling about 0.3% (1,939), according to the 2012 Census of Population and Housing conducted by Sri Lanka's Department of Census and Statistics.[23][21] This distribution reflects a Muslim-majority demographic in many coastal and interior areas, with Sinhalese concentrations increasing through post-independence colonization schemes that resettled farmers from the central highlands, elevating their share from around 20% in earlier censuses to nearly 39% by 2012.[24] While all major ethnic groups—Sinhalese, Tamils, and Moors—maintain longstanding ties to the region's arable lands and coastal resources based on pre-modern settlement patterns, these policies shifted balances without negating prior multicultural habitation. Religiously, the district aligns closely with ethnic lines: Islam predominates among Moors at 43.5% (281,987 adherents), Buddhism among Sinhalese at 38.7% (251,427), and Hinduism among Tamils at 15.9% (102,829), with Christians comprising a small 2.0% minority (13,129) and negligible others.[21][4] This pluralism, rooted in the Eastern Province's historical role as a crossroads of trade and migration, has sustained inter-community interactions amid periodic resource competitions, though census data underscores stable proportions post-civil war without evidence of disproportionate shifts favoring any single faith.[24]| Ethnic Group | Population (2012) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sri Lankan Moors | 281,702 | 43.4% |

| Sinhalese | 252,458 | 38.9% |

| Sri Lankan Tamils | 112,457 | 17.3% |

| Others (incl. Indian Tamils, Burghers, Malays) | 2,785 | 0.4% |

| Total | 649,402 | 100% |

| Religion | Population (2012) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Islam | 281,987 | 43.5% |

| Buddhism | 251,427 | 38.7% |

| Hinduism | 102,829 | 15.9% |

| Christianity | 13,129 | 2.0% |

| Others/Not stated | 30 | <0.1% |

| Total | 649,402 | 100% |

History

Pre-Colonial and Ancient Periods

Archaeological excavations in the Ampara district reveal evidence of early human habitation dating back to at least the 2nd century BCE, primarily through cave sites and monastic complexes associated with Buddhist civilization. Sites such as Rajagala, featuring drip-ledged caves, inscriptions, and faunal remains indicating settled activity, suggest proto-urban monastic communities supported by local resources.[26] Similarly, the Samangala Buddhist Monastery ruins, unearthed in recent digs, include structural remnants of viharas and stupas, pointing to organized religious and possibly agrarian settlements in the hinterlands.[28] The region formed part of the ancient Ruhuna (or Digamadulla) principality, a Sinhalese polity emerging around the 3rd century BCE and enduring until the 13th century CE, centered in the southeastern dry zone. Ruhuna served as a strategic refuge and power base during conflicts with northern kingdoms like Anuradhapura, with Ampara's terrain hosting defensive monastic outposts and agricultural hinterlands.[29] Epigraphic and structural evidence from sites like Thiruwaliwarpuram corroborates ties to this kingdom's Buddhist infrastructure, including ruins of stupas and assembly halls indicative of royal patronage under kings such as Dutugemunu.[30] Prominent Buddhist monuments, such as the Deeghawapi stupa constructed circa 161 BCE by King Dutugemunu, underscore the area's role in early Theravada networks, with brick foundations and relic chambers evidencing large-scale construction for rice-surplus supporting populations.[31] The Neelagiriseya stupa in nearby Lahugala, the largest in the Eastern Province, similarly dates to pre-1st century CE layers, reflecting hydraulic engineering for monastic sustenance.[32] Ancient irrigation networks, inferred from regional dry-zone systems documented in lithic inscriptions and chronicles, facilitated rice cultivation in Ampara's alluvial plains, with tanks and canals enabling wet-rice agriculture by the Anuradhapura period (circa 377 BCE–1017 CE).[33] However, direct epigraphic records specific to Ampara remain limited, with most evidence extrapolated from broader Ruhuna hydrology, emphasizing causal links between water control and demographic stability rather than mythic attributions.[34] Claims of pre-Buddhist Vedic influences lack robust local artifacts, appearing more as generalized Indo-Sri Lankan trade contacts without site-specific corroboration.[35]Colonial and Early Modern Era

The Portuguese initiated European involvement in Sri Lanka's eastern regions in the early 17th century, constructing the Batticaloa Fort in 1628 to safeguard maritime trade routes and extract resources such as elephants and spices from inland areas, including territories adjacent to present-day Ampara district.[36] This fortification facilitated control over local settlements, imposing tribute systems that disrupted traditional inland economies reliant on subsistence agriculture and herding.[37] The Dutch captured the fort in 1638, reconstructing and using it as a key outpost until 1796, when British forces assumed control amid the Napoleonic Wars' fallout.[38] Dutch administration emphasized coastal trade monopolies, with limited direct penetration into the arid interior of Ampara, though their policies of land grants to loyalists and suppression of local irrigation maintenance contributed to demographic stagnation and population dispersal in the region.[39] British rule, solidified after the 1815 Kandyan Convention granting full island control, shifted focus to systematic resource exploitation in the dry zone.[40] In Ampara, colonial authorities initiated irrigation restorations post-1818, rehabilitating ancient tanks and channels to enable rice cultivation and attract seasonal labor, marking early precursors to large-scale settlement schemes.[41] These efforts, coupled with the 1931 Land Settlement Ordinance, prompted modest demographic inflows of Sinhalese farmers from the wet zone and Tamil laborers, altering local land use from sparse pastoralism to proto-agricultural colonies without precipitating major ethnic shifts until post-independence.[42] Plantations remained peripheral, prioritizing export crops elsewhere, while Ampara served initially as a rest stop for colonial hunters exploiting its wildlife reserves.[1]Post-Independence Developments

The Gal Oya scheme, initiated in 1949 under Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake, represented Sri Lanka's inaugural large-scale post-independence development initiative, encompassing irrigation infrastructure, hydroelectric power, and agricultural colonization in the eastern dry zone encompassing Ampara. The project centered on damming the Gal Oya River to irrigate approximately 100,000 acres of arid land previously unsuitable for intensive farming, while resettling over 20,000 primarily Sinhalese families from densely populated wet-zone areas to establish paddy fields and reduce urban land pressure. This state-directed effort causally expanded cultivable acreage by channeling river flows into ancient tank systems, yielding empirical gains in rice output that contributed to national food self-sufficiency goals amid post-war shortages.[43][10] Agricultural productivity in the scheme's subdivisions demonstrably rose, with farmer-reported rice yields averaging 95 bushels per acre—about 10% above contemporaneous government benchmarks for similar dry-zone plots—attributable to reliable water supply and mechanized inputs like fertilizers introduced via extension services. However, implementation flaws, including top-down planning that sidelined local farmer input and uneven water distribution across blocks, hampered full potential, as evidenced by variable harvest recoveries during early drought cycles. The resettlement prioritized Sinhalese allottees under colonization policy, empirically intensifying land competition with indigenous Tamil and Muslim communities who held customary claims, thereby seeding disputes over tenure rights without formal adjudication mechanisms.[44][45] Administrative consolidation advanced in April 1961 with Ampara's designation as a distinct district headquarters, carved from Batticaloa's southern divisions including areas like Dehiattakandiya and Padiyatalawa, to streamline oversight of expanding settlements and irrigation networks. This restructuring accommodated population surges from ongoing dry-zone inflows, where colonists cleared malarial scrub for farms, doubling inhabited extents in project zones by the mid-1960s through targeted health campaigns and road linkages. Such growth empirically amplified regional output, with Gal Oya blocks accounting for measurable upticks in national paddy harvests—rising from under 1 million metric tons island-wide in 1950 to over 1.5 million by 1960—though sustained inefficiencies in maintenance persisted due to centralized bureaucracy over local governance.[41][46]Civil War and Aftermath

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a terrorist group seeking to establish a separate Tamil state, established a significant presence in Ampara district during the 1980s and 1990s as part of their insurgency in Sri Lanka's Eastern Province.[47] The LTTE conducted numerous attacks, including the September 17, 1999, Gonagala massacre, where militants killed 54 Sinhalese villagers, primarily women and children, in a targeted ethnic cleansing operation.[48] Government forces responded with counter-insurgency operations, leading to intense fighting that displaced thousands of civilians, particularly Tamils and Muslims, amid LTTE efforts to control eastern territories.[49] Clashes escalated in the 2000s, with LTTE bombings such as the April 2, 2007, bus attack in Ampara that killed 16 civilians, mostly women and children.[50] The district's multi-ethnic population suffered heavy human costs, including forced recruitment of child soldiers by the LTTE and widespread internal displacement, exacerbating ethnic tensions between Tamils, Muslims, and Sinhalese.[51] The December 26, 2004, Indian Ocean tsunami compounded the devastation in Ampara, where coastal areas saw significant loss of life and infrastructure damage, followed by aid distribution marred by ethnic favoritism, political interference, and harassment of aid workers, with resources often skewed toward government-controlled areas over LTTE-held zones.[52][53] The Sri Lankan military's decisive offensive in the Eastern Province from 2006 to 2007 recaptured LTTE strongholds, weakening their control over Ampara and setting the stage for the group's final defeat on May 18, 2009.[54] In the aftermath, the government initiated resettlement programs, facilitating the return of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to Ampara; by July 2, 2009, over 1,000 IDPs were resettled with UNHCR support, followed by thousands more to areas including Thirukovil and Kanchkudicharu, backed by allocations exceeding 314 million Sri Lankan rupees for rehabilitation.[55][56] While many returned, challenges persisted, including land disputes and incomplete infrastructure recovery, though empirical data indicate substantial progress in stabilizing the district post-victory.[57]Government and Politics

Administrative Structure

Ampara District is administered by a District Secretary, a central government appointee who coordinates policy implementation, resource allocation, and inter-agency collaboration across the district's 4,415 square kilometers. This office oversees development projects, disaster management, and statistical reporting, serving a population estimated at 744,150 as of 2024.[58][21] The district comprises 20 Divisional Secretariats, each managed by a Divisional Secretary responsible for local-level functions such as civil registration, welfare programs, and land administration. These divisions are subdivided into 503 Grama Niladhari units, the foundational administrative tier handling community-level services like identity documentation and grievance resolution.[59] The urban center of Ampara falls under the Ampara Urban Council, a local authority tasked with municipal governance including public sanitation, street lighting, and market regulation within its eight wards. As part of Sri Lanka's Eastern Province, the district integrates with the Eastern Provincial Council, which holds devolved authority over sectors like health and education, while remaining accountable to central ministries for fiscal and regulatory compliance.[60][61]Political Dynamics and Ethnic Influences

Ampara District's politics are shaped by its ethnic diversity, with Sinhalese comprising approximately 38.5% of the population, Sri Lankan Moors around 43.7%, and Sri Lankan Tamils about 15.4% as of the 2012 census, fostering a landscape of alliances and competition among ethnic-based voting blocs.[62] This composition drives electoral strategies where Sinhalese voters predominantly support national parties emphasizing unitary governance and post-war reconstruction, while Moors often back the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) or form tactical alliances, and Tamils align with the Tamil National Alliance (TNA).[63] Voter turnout in the district's Digamadulla electoral area averaged over 70% in recent national polls, reflecting high ethnic mobilization but also pragmatic cross-group coalitions to counterbalance dominance by any single community.[64] The party landscape features dominance by Sinhalese-majority parties such as the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) and United National Party (UNP), which secured the bulk of seats in the 2020 parliamentary elections for Digamadulla, with SLPP winning 5 of 7 seats on 58.93% of votes (423,529 ballots), compared to TNA's single seat on 10.62% and SLMC's on 9.5%.[64] These outcomes underscore empirical voting patterns where Sinhalese preferences for centralized authority prevail, often marginalizing separatist-leaning Tamil demands, while Muslim alliances with SLPP or UNP provide representation without fracturing the unitary framework.[65] Ethnic politics manifests in debates over devolution under the 13th Amendment, which grants limited provincial powers but faces resistance in Ampara due to fears of territorial fragmentation; proponents argue it enables local power-sharing, yet critics, including Sinhalese nationalists, contend it perpetuates division akin to LTTE-era separatism, which empirically stalled infrastructure and economic growth by prioritizing armed conflict over integration.[66] Post-2019 developments, following Gotabaya Rajapaksa's presidential victory and SLPP's parliamentary sweep, highlighted shifts amid national economic crises, with Ampara voters prioritizing stability and anti-corruption over ethnic concessions—evident in sustained SLPP support despite 2022 unrest.[67] LTTE separatism's legacy, including disrupted agriculture and displacement, is cited as a causal factor in the district's relative underdevelopment, with post-2009 reconstruction under unitary policies yielding measurable gains in roads and irrigation, though ethnic alliances remain fluid to navigate power-sharing without devolving into irredentist claims.[63] This dynamic favors pragmatic representation over grievance-based narratives, as turnout data shows cross-ethnic voting for development-focused platforms rather than rigid ethnic silos.[68]Economy

Agricultural Sector

The agricultural sector forms the economic foundation of Ampara District, with rice as the dominant crop, cultivated across extensive irrigated lowlands. The Gal Oya River Basin, spanning much of the district, accounts for nearly 25% of Sri Lanka's national paddy production, benefiting from the post-independence Gal Oya irrigation scheme that supports multiple cropping seasons through reservoirs and canal networks.[69] Paddy yields in Ampara have averaged around 4.5 metric tons per hectare during the Yala season in recent assessments, enabling the district to rank among Sri Lanka's leading producers despite its dry zone conditions.[70] Sugarcane and vegetables, including drought-resistant varieties like onions and chilies, supplement rice farming, with sugarcane directed toward local processing amid national production shortfalls. Over 50% of Ampara's employed population engages in agriculture, reflecting the sector's labor-intensive nature and reliance on smallholder operations.[71] [72] Irrigation advancements have driven output gains, yet vulnerabilities persist: recurrent droughts, exacerbated by erratic monsoons, have prompted adaptive measures such as early sowing and reduced water-intensive varieties among Ampara farmers. Post-civil war recovery since 2009 has boosted cultivated extents and total production, with agricultural output rising as displaced farmers resumed operations, though lingering land disputes and war-damaged infrastructure initially constrained productivity.[73] [74]Industry, Trade, and Emerging Sectors

Ampara District's non-agricultural economy remains underdeveloped, characterized by small-scale fishing and limited agro-processing activities rather than large-scale industrialization. The district's coastal areas support marine fishing, with annual production showing a positive trend, reaching approximately 53,505 metric tons as reported in recent fisheries assessments, primarily through artisanal methods using mechanized boats and gillnets. These operations contribute to local trade, with fish products often transported to nearby ports like Batticaloa for processing and export, though infrastructure constraints limit efficiency. Agro-processing is nascent, focusing on value addition to local produce such as drying and packaging fish, but lacks significant investment due to historical disruptions.[75] Trade in Ampara serves as a regional linkage, facilitating the movement of goods between inland agricultural zones and eastern ports, yet volumes are modest owing to poor connectivity and past conflict damage to roads and markets. The district's economy experienced setbacks from the Sri Lankan Civil War (1983–2009), which destroyed fishing infrastructure, displaced communities, and deterred investment in non-agricultural sectors, leading to persistent underutilization of coastal resources.[76] Post-war recovery has been uneven, with fishing and trade rebounding modestly but constrained by war legacies like asset destruction rather than ongoing systemic barriers.[77] Emerging sectors hold potential in rural tourism, leveraging Ampara's beaches and wildlife reserves. Areas like Arugam Bay attract surfing enthusiasts, while national parks such as Kumana and Gal Oya offer safaris for observing elephants, birds, and other fauna, with visitor interest growing post-2009.[78] However, the 2022 economic crisis exacerbated challenges, causing fuel and import shortages that disrupted fishing operations and tourism logistics, contributing to a national contraction that rippled to local GDP through reduced trade and visitor numbers.[79] Development efforts emphasize eco-tourism to capitalize on biodiversity, but realization depends on infrastructure improvements to overcome war-induced lags.[80]Infrastructure and Transportation

Road and Rail Networks

The primary road connecting Ampara District to major urban centers is the A15 trunk road, which links Batticaloa to Trincomalee and passes through key areas in the district such as Valachchenai, facilitating regional travel and goods transport.[81] Access to Colombo, approximately 300 kilometers west, occurs via interconnecting national highways including segments of the A11 and A6 through Polonnaruwa, though these routes traverse varied terrain prone to seasonal flooding.[82] District-level roads, including B-class routes like B017 (Ampara Town Roads), form a network of over 1,000 kilometers supporting local agriculture and settlements, with upgrades emphasizing resurfacing and bridge reconstruction to enhance all-weather access.[81] Post-2009, following the Sri Lankan Civil War, international funding drove significant rehabilitations; the Asian Development Bank supported improvements to 200 kilometers of rural roads in Ampara to boost connectivity for 150,000 residents, while World Bank initiatives targeted provincial roads with resurfacing in flood-vulnerable zones.[82][10] Rail infrastructure remains limited, with Ampara lacking operational stations; the nearest line is the Batticaloa Railway, terminating 60 kilometers north at Batticaloa station, which handles modest passenger volumes of around 500 daily commuters and freight primarily for coastal trade. Extensions from Batticaloa southward to Ampara and further to Pottuvil have been proposed since the early 2010s, with land acquisition completed by 2019, aiming to integrate the district into the national rail grid for freight hauling of agricultural outputs like rice, though construction delays persist due to funding and environmental assessments.[83] Post-2009 investments focused more on roads than rail, reflecting priorities for immediate post-conflict mobility over long-term line development.[82]Utilities and Public Services

Electricity supply in Ampara district is managed primarily through the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), with the national grid achieving nearly 100% household coverage across Sri Lanka by 2016, including rural areas in Ampara.[84] Specific initiatives, such as the Asian Development Bank's Sustainable Power Project, have electrified over 12,200 remote households in Ampara's Eastern Province villages, enhancing supply reliability.[85] Recent infrastructure developments include the completion of a 12-kilometer 33kV distribution line from Ampara to Uhana in 2024, improving access in underserved eastern areas, and the grid connection of a 5MW solar plant in Ampara in 2025, contributing to renewable integration.[86][87] Water supply infrastructure has expanded significantly via the National Water Supply and Drainage Board (NWSDB), with a major turnkey project delivering piped treated drinking water to 300,000 residents in Ampara district, and plans to extend coverage to an additional 350,000, reaching a total of 611,000 people.[88] The Ampara District Water Supply Scheme, initiated post-independence and augmented through international contracts like Outotec's €70 million delivery in the early 2010s, focuses on urban and rural piped systems sourced from local reservoirs.[89][90] However, the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami severely contaminated coastal groundwater aquifers in Ampara, the most affected eastern district with over 10,000 deaths and widespread infrastructure damage, necessitating extensive post-disaster rehabilitation.[91][92] Public services face ongoing challenges, including repairs from civil war disruptions to utilities and the national economic crisis of 2022, which imposed rolling power cuts of up to three hours daily across Sri Lanka due to fuel shortages, impacting Ampara's grid-dependent systems.[93] Waste management remains strained, particularly in urban centers like Ampara town, where municipal solid waste practices are in crisis amid rising generation rates projected to reach 1 kg per person daily by 2025; efforts include UNOPS-supported integrated programs and EU-funded remediation in Ampara district since 2012.[94] Telecommunications coverage is robust, with 3G, 4G, and emerging 5G networks from providers like Airtel, which expanded 4G sites in Ampara in recent years, alongside Dialog, Hutch, and Mobitel offering broad mobile and broadband access throughout the district.[95][96]Culture and Society

Cultural Heritage and Traditions

Ampara District's cultural heritage reflects its multi-ethnic composition, encompassing Sinhalese Buddhist, Tamil Hindu, and Moor Muslim communities, manifested through ancient religious sites and shared agricultural traditions. Predominant among these are Buddhist archaeological monuments, such as the Deegavapi Stupa in Ninthavur, an ancient structure dating to the 2nd century BCE and traditionally associated with visits by the Buddha during his third visit to Sri Lanka, underscoring early monastic settlements in the region.[5] Similarly, the Buddhangala Monastery, a rock temple located 7 kilometers north of Ampara town, houses a dagoba containing relics attributed to the Buddha and features cliffside hermitages used by meditating monks, with inscriptions evidencing its use from the 2nd century BCE onward.[97][98] Other significant Buddhist sites include the Muhudu Maha Vihara at Pottuvil, constructed over 2,000 years ago adjacent to a coastal beach, and the Rajagala Archaeological Reserve, which preserves the ancient Ariyakara Viharaya amid mountain ruins from the pre-Christian era, highlighting Ampara's role in early Sri Lankan Buddhist history.[99][100] Tamil Hindu kovils and Moor mosques, while integral to local worship, are less prominently documented in archaeological records for the district, though they support community-specific rituals amid the Sinhalese-majority Buddhist landscape.[101] Traditional practices emphasize agricultural cycles, with the Tamil harvest festival Thai Pongal, observed annually in mid-January, involving rituals of gratitude to the sun, earth, and livestock through offerings of boiled rice and jaggery, reflecting Ampara's agrarian economy reliant on paddy cultivation.[102] Buddhist Vesak, marking the Buddha's birth, enlightenment, and death, features district-wide illuminations, processions, and almsgiving, fostering inter-community participation in areas like Uhana.[103] These multi-faith observances, including Moor Eid celebrations, promote harmonious expressions of devotion without documented ethnic exclusivity in routine practice. Post-2004 tsunami restorations, coordinated through national heritage bodies, have aided recovery of coastal sites like Muhudu Maha Vihara, though primary efforts focused on structural rebuilding rather than expansive intangible heritage programs.[104]Education and Healthcare

Ampara District maintains a network of government schools, with 437 public institutions reported as of 2016, serving primary through secondary levels across Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim mediums of instruction.[105] Higher education is anchored by the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, established in 1995 in Oluvil, offering undergraduate and postgraduate programs in fields such as management, arts, and applied sciences to regional students.[106] The Open University of Sri Lanka operates an Ampara Study Centre, providing distance learning options for adult and working learners.[107] Literacy rates for individuals aged 10 and above in Ampara stood at 90.6% in 2021, below the national average of 93.3%, with males at 93.8% and females at 87.8%, indicating persistent gender disparities potentially linked to cultural factors in the district's diverse ethnic composition, including significant Muslim communities.[108] These gaps persist despite national efforts to expand access, as Ampara's rural and post-conflict context contributes to uneven enrollment and completion rates compared to urban districts.[108] Healthcare infrastructure includes the District General Hospital Ampara, a tertiary facility serving the district's approximately 744,000 residents as of 2022, alongside base hospitals in Akkaraipattu and Dehiattakandiya, and specialized institutions like Ashraff Memorial Hospital in Kalmunai.[109][110] Infant mortality rates in Ampara have remained low post-civil war, averaging 2.0–4.2 per 1,000 live births from 2012 to 2019, reflecting improvements in maternal and child health services amid national declines, though resource allocation faces pressures from population growth exceeding 20% since 2007.[111][112][113] These outcomes suggest effective basic interventions, yet disparities in access persist in remote areas, straining facilities amid rising demand.[111]Social Challenges and Ethnic Relations

Ampara district contends with persistent poverty, particularly in rural and coastal areas, where the headcount index stood at approximately 11% in 2016, exceeding the national average amid structural economic vulnerabilities.[114] The 2022 economic crisis amplified these pressures nationwide, doubling poverty rates to around 25%, with Eastern Province districts like Ampara facing compounded risks due to dependence on agriculture and limited diversification.[115] Youth unemployment represents another acute challenge, with national rates reaching 26.3% in 2023, disproportionately affecting post-war regions like Ampara where skill mismatches and limited industrial opportunities persist.[116] In the Eastern Province, youth comprise a significant share of total unemployment, driven by inadequate vocational training and migration constraints following the 2009 conflict resolution.[117] Inter-ethnic relations in Ampara, home to Sinhalese, Tamil, and Muslim communities, exhibit a mix of coexistence and underlying tensions post-2009. Empirical studies in the district's southeastern coastal regions document functional relationships among groups, facilitated by shared economic activities like fishing, though historical animosities occasionally resurface in Sinhalese-Muslim interactions due to perceived cultural encroachments.[118] [119] Government-led initiatives, including the Office for National Unity and Reconciliation's programs in the Eastern Province since 2024, promote dialogue and community events to foster integration, emphasizing national unity over devolved autonomies favored by some minority advocates.[120] Non-governmental efforts, such as peacebuilding projects in multi-ethnic divisions, aim to build trust through joint economic ventures, though surveys reveal persistent suspicions tied to wartime displacements rather than outright hostility.[121]Controversies and Conflicts

Role in Sri Lankan Civil War

Ampara District, situated in Sri Lanka's Eastern Province with its ethnically diverse population of Sinhalese, Tamils, and Muslims, became a strategic battleground during the Sri Lankan Civil War (1983–2009), as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) sought to incorporate the area into their envisioned independent Tamil state of Eelam, while the government forces aimed to maintain national unification. The LTTE, designated a terrorist organization by over 30 countries for tactics including suicide bombings and child soldier recruitment, conducted incursions and attacks targeting security forces and civilians to assert control, prompting robust countermeasures from the Sri Lankan military, including the Special Task Force (STF). These operations exacerbated ethnic tensions, leading to mass displacements and high civilian casualties.[122] In the late 1980s, LTTE militants began establishing presence in Ampara through guerrilla incursions, clashing with rival Tamil groups like the Tamil National Army (TNA) and exploiting local support amid Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) operations. By early 1990, escalating violence culminated on June 11, 1990, when LTTE cadres overran the Pottuvil police station, massacring over 120 surrendered policemen—sparing Tamils but executing Sinhalese and Muslim officers—to provoke a broader conflict and eliminate state outposts. This atrocity triggered war resumption, with LTTE withdrawing from urban centers by mid-June but launching retaliatory strikes, including the killing of four Muslims in Oddaimavadi who had welcomed advancing army troops. Government forces responded with arrests and cordon operations, but LTTE tactics shifted to civilian targeting, contributing to over 3,000–5,000 Tamil deaths in the district within months.[122] LTTE's ethnic cleansing efforts intensified against the Muslim population in 1990, aiming to homogenize claimed Eelam territories; between July and August, militants massacred around 700 Muslims in sites like Kurukkalmadam, Kattankudy, and Eravur, using mosque attacks and summary executions to force compliance or flight. These pogroms, coupled with LTTE demands for Muslims to vacate Tamil-majority areas, displaced tens of thousands across the Eastern Province, including over half of Ampara's approximately 60,000 Tamils by late 1990, with refugees crowding camps in Thirukkovil and Thambiluvil. An August 12, 1990, LTTE incursion into Veeramunai further inflamed retaliatory violence by Muslim home guards against Tamil refugees, killing hundreds in a Pillayar temple, underscoring the LTTE's role in igniting inter-communal strife through calculated terror.[122][123] Mid-1990s clashes highlighted Ampara's frontline status, with LTTE overrunning the STF camp at Pulukunawa on December 11, 1996, killing dozens of police in a coordinated assault that demonstrated their ambush expertise against isolated outposts. Civilian massacres persisted, exemplified by the September 18, 1999, Gonagala attack, where LTTE cadres hacked to death 54 Sinhalese villagers—including 10 children and 14 from one family—using machetes and axes to terrorize border settlements and disrupt government-held areas. Such incidents, part of LTTE's pattern of displacing non-Tamils via atrocities, resulted in thousands more internally displaced in Ampara, with naval skirmishes along the district's coast amplifying supply interdictions by Sea Tigers against government patrols. Sri Lankan forces countered with STF offensives and aerial support, reclaiming territory but at the cost of further civilian hardship amid LTTE's indiscriminate tactics.[124][122]Land Disputes and Post-War Tensions

The Gal Oya irrigation and settlement scheme, launched in the late 1940s and expanded in the 1950s, resettled thousands of primarily Sinhalese farmers on state lands in Ampara district, areas previously used by Tamil and Moor communities for paddy cultivation and pastoralism under customary arrangements.[125] This state-sponsored colonization, governed by the Land Development Ordinance, significantly increased the Sinhalese population share in Ampara from negligible levels pre-independence to over 40% by the 1980s, fostering enduring grievances over historical land access and contributing to ethnic polarization that intensified during the civil war.[126] Post-2009, war-related destructions and displacements—displacing over 1 million in the Eastern Province, including Ampara—exacerbated these claims as returning internally displaced persons (IDPs) confronted competing entitlements, with Tamil and Moor returnees often alleging encroachment by Sinhalese settlers or state reallocation.[127] Military occupations persisted after the war's end, delaying civilian returns; in Ashraf Nagar, Ampara, the army evicted 69 Muslim families from their lands on November 5, 2011, for unspecified security and commercial uses, leaving them displaced without compensation or restitution as of 2017.[127] Similarly, in Panama, Ampara, security forces seized approximately 665 acres from Sinhalese villagers in July 2010 for tourism developments like resorts and conference centers; a February 2015 cabinet decision ordered release of most land except 25 acres, and a March 2016 court ruling favored residents after their forcible re-entry, yet air force and navy presence continued amid overlapping claims by forest and archaeology departments for an additional 591 acres.[127] In Wattamadu, a 2010 central government declaration of 4,000 acres as a forest reserve invalidated prior legal permits held by Tamil and Muslim paddy farmers and herders, prompting ongoing court challenges despite multi-ethnic organizations' protests over disrupted livelihoods.[126] State declarations for heritage sites have fueled further disputes in Muslim-majority areas; at Muhudu Maha Viharaya in Pottuvil, a 2020 survey claimed 72 acres as a sacred Buddhist site—supported by presidential task forces and military—opposed by 300 affected Muslim families with ownership documents, culminating in a 2023 gazette notification under the Town and Country Planning Ordinance that restricted access.[128] Analogous cases include Manikkamadu Mayakkalli Hill in Irakkamam, where a 2014 archaeology gazette and 2016-2018 Buddhist statue and temple constructions on private land displaced Muslim cultivators, and Mullikulam Malai in Addalaichenai, where a 1999 archaeological reserve claim led to halted 2022 temple work amid local resistance.[128] These actions, often rationalized by government agencies for cultural preservation or development, have been critiqued by NGOs for enabling demographic shifts via "Sinhalisation," though officials maintain they address legal encroachments or public interest without ethnic targeting.[128][127] Nationally, the government asserted by 2018 that 80-85% of wartime-occupied lands in the north and east had been returned, yet Ampara-specific returns remain opaque, with reports indicating at least 1,406 Muslim farming families still affected by non-restitution in 2017.[127][129] Uncoordinated state interventions—such as post-2009 pressures on multi-ethnic smallholders in sugarcane zones to revert from paddy amid Hingurana factory revival—have compounded economic insecurities, linking directly to war-induced tenure uncertainties and sustaining inter-ethnic mistrust through protests and litigation rather than resolution.[126] Such tensions manifest in localized clashes, as underlying land scarcities amplify communal frictions in a district where ethnic groups compete for arable resources amid incomplete post-war reconstruction.[128]References

- https://whc.[unesco](/page/UNESCO).org/en/tentativelists/6454/