Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tamils

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Tamiḻ | |

|---|---|

| People | Tamiḻar |

| Language | Tamiḻ |

| Country | Tamiḻ Nāṭu |

| Part of a series on |

| Tamils |

|---|

|

|

|

The Tamils (/ˈtæmɪlz, ˈtɑː-/ TAM-ilz, TAHM-), also known by their endonym Tamilar,[d] are a Dravidian ethnic group who natively speak the Tamil language and trace their ancestry mainly to the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. The Tamil language is one of the longest-surviving classical languages, with over two thousand years of written history, dating back to the Sangam period (between 300 BCE and 300 CE). Tamils constitute about 5.7% of the Indian population and form the majority in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu and the union territory of Puducherry. They also form significant proportions of the populations in Sri Lanka (15.3%), Malaysia (7%) and Singapore (5%). Tamils have migrated world-wide since the 19th century CE and a significant population exists in South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, as well as other regions such as the Southeast Asia, Middle East, Caribbean and parts of the Western World.

Archaeological evidence from Tamil Nadu indicates a continuous history of human occupation for more than 3,800 years. In the Sangam period, Tamilakam was ruled by the Three Crowned Kings of the Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas. Smaller Velir kings and chieftains ruled certain territories and maintained relationship with the larger kingdoms. Urbanisation and mercantile activity developed along the coasts during the later Sangam period with the Tamils influencing the regional trade in the Indian Ocean region. Artifacts obtained from excavations indicate the presence of early trade relations with the Romans. The major kingdoms to rule the region later were the Pallavas (3rd–9th century CE), and the Vijayanagara Empire (14th–17th century CE).

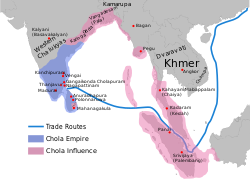

The island of Sri Lanka often saw attacks from the Indian mainland with the Cholas establishing their influence across the island and across several areas in Southeast Asia in the 10th century CE. This led to the spread of Tamil influence and contributed to the cultural Indianisation of the region. Scripts brought by Tamil traders like the Grantha and Pallava scripts, induced the development of many Southeast Asian scripts. The Jaffna Kingdom later controlled the Tamil territory in the north of the Sri Lanka from 13th to 17th century CE. European colonization began in the 17th century CE, and continued for two centuries until the middle of the 20th century.

Due to its long history, the Tamil culture has seen multiple influences over the years and have developed diversely. The Tamil visual art consists of a distinct style of architecture, sculpture and other art forms. Tamil sculpture ranges from stone sculptures in temples, to detailed bronze icons. The ancient Tamil country had its own system of music called Tamil Pannisai. Tamil performing arts include the theatre form Koothu, puppetry Bommalattam, classical dance Bharatanatyam, and various other traditional dance forms. Hinduism is the major religion followed by the Tamils and the religious practices include the veneration of various village deities and ancient Tamil gods. A smaller number are also Christians and Muslims, and a small percentage follow Jainism and Buddhism. Tamil cuisine consist of various vegetarian and meat items, usually spiced with locally available spices. Historian Michael Wood called the Tamils the last surviving classical civilization on Earth, because the Tamils have preserved substantial elements of their past regarding belief, culture, music, and literature despite the influence of globalization.[12]

Etymology

[edit]Tamil is derived from the name of the language.[13] The people are referred to as Tamiḻar in Tamil language, which is etymologically linked to the name of the language.[14] The origin and precise etymology of the word Tamil is unclear with multiple theories attested to it.[15] Kamil Zvelebil suggests that the term tamiz might have been derived from tam meaning "self" and "-iz" having the connotation of "unfolding sound". Alternatively, he suggests a derivation of tamiz < tam-iz < *tav-iz < *tak-iz, meaning "the proper process (of speaking)".[16] Franklin Southworth suggests that the name comes from tam-miz > tam-iz meaning "self-speak", or "our own speech".[17]

It is unknown whether the term Tamila and its equivalents in Prakrit such as Damela, Damila, or Tamira was first used as a self designation or by outsiders. The Hathigumpha inscription from Udayagiri in Eastern India dated to the second century BCE,[18][19] describes a T[r]amira samghata (Confederacy of Tamil rulers), which was in existence for the previous 113 years.[20] Epigraphical evidence from the second century BCE mentioning Damela or Dameda from ancient Sri Lanka have been found.[21] In the Buddhist Jataka texts, there is a mention of a Damila-rattha (Tamil dynasty).[22][23] Greek historian Strabo (first century BCE) mentions that the Roman Emperor Augustus received an ambassador from Pandyan of Dramira.[24] An inscription from Amaravati dated to third century CE refers to a Dhamila-vaniya (Tamil trader).[25]

History

[edit]In India

[edit]Pre-historic period (before 4th century BCE)

[edit]Archaeological evidence suggests the region was first inhabited by hominids over 400 millennia ago.[26][27] Artifacts recovered in Adichanallur by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) indicate megalithic urn burials, dating from back to 1500 BCE.,[28][29][30] which are also described in early Tamil literature.[31] Neolithic celts with the Indus script dated between 15th and 20th century BCE indicate the use of early Harappan language.[32][33] Excavations at Keezhadi have revealed a large urban settlement, with the earliest artefact dated to 580 BCE, during the time of urbanization in the Indo-Gangetic plain.[34] Further epigraphical inscriptions found at Adichanallur use Tamil Brahmi, a rudimentary script dated to 5th century BCE.[35] Potsherds uncovered from Keeladi indicate a script which might be a transition between the Indus Valley script and Tamil Brahmi script used later.[36]

Sangam period (3rd century BCE–3rd century CE)

[edit]

The Sangam period lasted from 3rd century BCE to 3rd century CE with the main source of history during the period coming from the various Sangam literature.[37][38] Ancient Tamilakam was ruled by a triumvirate of monarchical states, Cheras, Cholas and Pandyas.[39] These kings are referred to as Vāṉpukaḻ Mūvar (Three glorified by heaven) in the Sangam literature.[40] The Cheras controlled the western part of Tamilkam, the Pandyas controlled the south, and the Cholas had their base in the Kaveri delta.[41][42] They are mentioned in the inscriptions from the Mauryan Empire dated to third century BCE.[43] Kalinga inscriptions from the second century BCE refers to a confederacy of the Tamil kingdoms.[44] The three kings called Vendhar ruled over several hill tribes headed by the Velir chiefs and settlements headed by clan chiefs called Kizhar.[45] The rulers of smaller territories were referred to as Kurunilamannar, with Purananuru mentioning the names of many such chieftains.[46]

The Sangam period rulers patronized multiple religions including vedic religion, Buddhism and Jainism and sponsored some of the earliest Tamil literature with the oldest surviving work being Tolkāppiyam, a book of Tamil grammar.[47] Purananuru describes the public life and various unique cultural practices that existed during the period. The text talks about the Vedic Sacrifices performed by the kings as described in the Vedas and the rituals performed for the dead.[48][49]

Agriculture was an important occupation during the period, and there is evidence that networks of irrigation channels were built as early as the 3rd century BCE. The Sangam literature describe fertile lands and people organised into various occupational groups. The governance of the land was through hereditary monarchies, although the sphere of the state's activities and the extent of the ruler's powers were limited through the adherence to an established order.[50][51]

The kingdoms had significant diplomatic and trade contacts with other kingdoms to the north and with the Romans. Roman coins and other epigraphical evidence from South India and potsherds with Tamil writing found in excavations along the Red Sea indicate the presence of Roman commerce with the ancient Tamilakam.[52][53] Much of the commerce from the Romans and Han China were facilitated via seaports including Muziris and Korkai with spices being the most prized goods along with pearls and silk.[54][55] There is evidence of emissaries sent to the Roman Emperor Augustus by the Pandya kings.[24] An anonymous Greek traveler's account from first century CE, Periplus Maris Erytraei, describes the ports of the Pandya and Chera kingdoms in Damirica and their commercial activity in detail. It also describes that the chief exports of the ancient Tamils were pepper, malabathrum, pearls, ivory, silk, spikenard, diamonds, sapphires, and tortoiseshell.[56]

Medieval era (4th–13th century CE)

[edit]

From the fourth century CE, the region was ruled by the Kalabhras, warriors belonging to the Vellalar community, who were once feudatories of the three ancient Tamil kingdoms.[57] The Kalabhra era is referred to as the "dark period" of Tamil history, and information about it is generally inferred from any mentions in the literature and inscriptions that are dated many centuries after their era ended.[58] Around the seventh century CE, the Kalabhras were overthrown by the Pandyas and Cholas.[59][60] Though they existed previously, the period saw the rise of the Pallavas in the sixth century CE under Mahendravarman I, who ruled parts of South India with Kanchipuram as their capital.[61] The Pallavas were noted for their patronage of architecture.[62] Throughout their reign, the Pallavas remained in constant conflict with the Cholas, the Pandyas and other kingdoms of Chalukyas of Badami and the Rashtrakutas.[63] The Pandyas were revived by Kadungon towards the end of the sixth century CE and with the Cholas in obscurity in Uraiyur, the Tamil country was divided between the Pallavas and the Pandyas.[64] The area west of the Western Ghats became increasingly distinct from the eastern parts.[65] A new language Malayalam evolved from Tamil in the region and the socio-cultural transformation was altered further by the migration of Sanskrit-speaking Indo-Aryans from Northern India in the eighth century CE.[66][67]

The Cholas were revived in the ninth century CE by Vijayalaya Chola and the last Pallavas ruler Aparajitavarman was defeated by the Chola prince Aditya I.[68] After the defeat of the Pallavas, the Cholas became the dominant kingdom with the capital at Thanjavur. The Chola influence expanded subsequently with Rajaraja I conquering the entire Southern India and parts of present-day Sri Lanka and Maldives, and increased Chola influence across the Indian Ocean in the eleventh century CE.[69][70] Rajaraja brought in administrative reforms including the reorganisation of Tamil country into individual administrative units.[71] Under his son Rajendra Chola I, the Chola empire reached its zenith and stretched as far as Bengal in the north and across the Indian Ocean.[72] He defeated the Eastern Chalukyas and the Chola navy invaded the Srivijaya Empire in South East Asia.[73] The Cholas had trade links with the Chinese Song Dynasty and across Southeast Asia.[74][75] The Cholas built many temples with the most notable being the Brihadisvara Temple at Thanjavur.[76] The latter half of the eleventh century saw the union of Chola and Vengi kingdoms under Kulottunga I.[77] The Cholas repulsed attacks from the Western Chalukyas and maintained its influence over the various kingdoms of Southeast Asia.[78][79] According to historian Nilakanta Sastri, Kulottunga avoided unnecessary wars and had a long and prosperous reign characterized by unparalleled success that laid the foundations of the empire for the next 150 years.[80]

The eventual decline of Chola power began towards the end of Kulottunga III's reign in the thirteenth century CE.[73] The Pandyas again reigned supreme under Maravarman Sundara I and defeated the Cholas under Rajaraja III.[81] Though the Cholas were revived briefly with the aid of Hoysalas, civil war between Rajaraja and Rajendra III weakened them further.[82] With the Hoysalas later siding with the Pandyas, the Pandyas consolidated control over the region.[83] The Pandya empire reached its zenith in the thirteenth century CE under Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan I after he defeated the Hoysalas, the Kakatiyas and captured parts of Sri Lanka. The Pandyas ruled from their capital of Madurai and expanded trade links with other maritime empires.[84] Venetian explorer Marco Polo mentioned the Pandyas as the richest empire in existence.[85] The Pandyas also built a number of temples including the Meenakshi Amman Temple at Madurai.[86] In the fourteenth century CE, the Pandyan empire was engulfed in a civil war and also faced repeated invasions by the Delhi Sultanate.[87] In 1335, the Pandyan capital was conquered by Jalaluddin Ahsan Khan and the short-lived Madurai Sultanate was established.[88][89]

Vijayanagar and Nayak period (14th–17th century CE)

[edit]The Vijayanagara kingdom was founded in 1336 CE.[90] The Vijayanagara empire eventually conquered the entire Tamil country by c. 1370 and ruled for almost two centuries.[91] In the sixteenth century, Vijaynagara king Krishnadeva Raya was forced to intervene in the conflict between their vassals, the Cholas and the Pandyas.[92][93] The Nayak governor under Raya briefly took control of Madurai before it was restored to the empire.[94] The Vijayanagara empire was defeated in the Battle of Talikota in 1565 by a confederacy of Deccan sultanates.[95] The Nayaks, who were the military governors in the Vijaynagara empire, took control of the region amongst whom the Nayaks of Madurai and Nayaks of Thanjavur were the most prominent.[96][97][98] They introduced the palayakkararar system and re-constructed some of the temples in Tamil Nadu including the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai.[99]

Later conflicts and European colonization (17th to 20th century CE)

[edit]

In the 18th century, the Mughal Empire administered the region through the Nawab of the Carnatic with his seat at Arcot, who defeated the Madurai Nayaks.[100] The Marathas attacked several times and defeated the Nawab after the Siege of Trichinopoly (1751-1752).[101][102][103] This led to a short-lived Thanjavur Maratha kingdom.[104] Europeans started to establish trade centres from the 16th century along the eastern coast. The Portuguese arrived in 1522 followed by the Dutch and the Danes.[105][106][107] In 1639, the British East India Company obtained a grant for land from the Vijayanager emperor and the French established trading posts at Pondichéry in 1693.[108][109][110] After several conflicts between the British and the French, the British established themselves as the major power in the eighteenth century CE.[111] The British regained control of Madras in 1749 through the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle and resisted a French siege attempt in 1759.[112][113][114]

The British East India Company demanded tax collection rights, which led to constant conflicts with the local Palaiyakkarars and resulted in the Polygar Wars. Puli Thevar was one of the earliest opponents, joined later by Rani Velu Nachiyar and Kattabomman in the first series of Polygar wars.[115][116] The Maruthu brothers along with Oomaithurai, formed a coalition with Dheeran Chinnamalai and Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja, which fought the British in the Second Polygar War.[117] In the later 18th century, the Mysore kingdom captured parts of the region and engaged in constant fighting with the British which culminated in the four Anglo-Mysore Wars.[118] By the late eighteenth century CE, the British had conquered most of the region and established the Madras Presidency with Madras as the capital.[119][120] On 10 July 1806, the Vellore mutiny, which was the first instance of a large-scale mutiny by Indian sepoys against the British East India Company, took place in Vellore Fort.[121] After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British Parliament passed the Government of India Act 1858, which transferred the governance of India from the East India Company to the British crown, forming the British Raj.[122][123]

Failure of the summer monsoons and administrative shortcomings of the Ryotwari system resulted in two severe famines in the Madras Presidency, the Great Famine of 1876–78 and the Indian famine of 1896–97 which killed millions and the migration of many Tamils as bonded laborers to other British countries eventually forming the present Tamil diaspora.[124] The Indian Independence movement gathered momentum in the early 20th century with the formation of the Indian National Congress, which was based on an idea propagated by the members of the Theosophical Society movement after a Theosophical convention held in Madras in December 1884.[125][126] Various Tamils were contributors to the Independence movement including V. O. Chidambaram Pillai, Subramaniya Siva and Bharatiyar.[127] The Tamils formed a significant percentage of the members of the Indian National Army (INA), founded by Subhas Chandra Bose.[128][129]

Post Indian Independence (1947–present)

[edit]After the Independence of India in 1947, the Madras Presidency became Madras state, comprising present-day Tamil Nadu and parts of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala. The state was further re-organised as a state for Tamils when the boundaries were redrawn linguistically in 1956 into the current shape.[130][131] On 14 January 1969, Madras state was renamed Tamil Nadu, meaning "Tamil country".[132][133] In 1965, Tamils agitated against the imposition of Hindi and in support of continuing English as a medium of communication which eventually led to English being retained as an official language of India alongside Hindi.[134] After experiencing fluctuations in the decades immediately after Indian independence, the Human Development Index of the Tamils have consistently improved due to reform-oriented economic policies and in the 2000s, the region has become one of the most urbanized states in the country.[135][136]

In Sri Lanka

[edit]Pre-Anuradhapura period (before fifth century CE)

[edit]

There are various theories from scholars over the presence of Tamil people in Sri Lanka. Historian K. Indrapala states that Tamil replaced a previous language of an indigenous mesolithic population, who later became the Eelam Tamils and the cultural diffusion happened well before the arrival of Sinhalese people in Sri Lanka.[138] Eelam Tamils consider themselves lineal descendants of the aboriginal Naga and Yaksha people of Sri Lanka. A cobra totem known as Nakam in the Tamil language is still part of the Tamil tradition in Sri Lanka.[139] Remains of settlements and megalithic burial sites of people culturally similar to those of present-day Sri Lanka and Tamil Nadu in modern India have been excavated at Pomparippu on the west coast and in Kathiraveli on the east coast of the island. These epigraphical evidence have been dated to a period between fifth century BCE and second century CE.[140][141] Cultural similarities in burial practices in South India and Sri Lanka were dated by archeologists to the beginning of the Iron Age in the region around twelfth century BCE. There were specific migration routes that extended from South India to the island. These people moved further to the South of the island, and intermingled with the existent people.[142]

Anuradhapura period (4th century BCE to 10th century CE)

[edit]Black and red ware potsherds found in Sri Lanka from the early reign of Anuradhapura kingdom, indicate a similar cultural connection with the people of South India.[143] The Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on them indicate Tamil clan names such as Parumakal, Ay, Vel, Utiyan, Ticaiyan, Cuda and Naka, which points to the presence of Tamils in the region.[144] Excavations in Poonakari in the north of the island have yielded several inscriptions including the mention of vela, a name related to velirs of the ancient Tamil country.[145] Epigraphical evidence of people identified as Damelas (the Prakrit word for Tamil people) from the second century CE have been found in Anuradhapura, the capital city of the northern Rajarata region.[146]

Historical records mention that the three Tamil kingdoms were involved in the island's affairs from second century BCE.[147][148] Chola king Ellalan captured the Anuradhapura Kingdom from 205 BCE to 161 BCE.[149] Tamil soldiers from Tamilakam came to Anuradhapura in large numbers in the seventh century CE with the local chiefs and kings relying on them.[150] In the eighth century CE, various Tamil villages collectively known as Demel-kaballa (Tamil allotment), Demelat-valademin (Tamil villages), and Demel-gam-bim (Tamil villages and lands) were established.[151] In the ninth and tenth centuries CE, Pandya and Chola incursions started in the island which culminated with the Chola annexation of the island.[150]

Polonnaruwa and Jaffna kingdom (11th–15th century CE)

[edit]

The Chola influence lasted until the latter half of the eleventh century CE and the Chola decline was followed by the restoration of the Polonnaruwa monarchy.[150][152] In 1215, following Pandya invasions, the Tamil-dominant Aryacakravarti dynasty established the Jaffna Kingdom on the Jaffna peninsula and in parts of northern Sri Lanka.[153] In the fourteenth century CE, the Aryacakaravarthi expansion into the south of the island was halted by Alagakkonara, who belonged to a feudal family from Kanchipuram that migrated to Sri Lanka in the previous century and converted to Buddhism.[154] He served as the chief minister of the Sinhalese king Parakramabahu V (1344–59 CE) and his descendant Vira Alakeshwara briefly became the king later before the Ming admiral Zheng He overthrew him in 1409 CE after which the influence of his family declined.[155] The caste structure of the Sinhalese also accommodated Hindu immigrants from South India, which led to the emergence of new Sinhalese caste groups such as the Radala, the Salagama, the Durava and the Karava.[156][157]

Later conflicts and European colonization (16th–20th century CE)

[edit]The Aryachakaravarthi dynasty continued to rule over large parts of northeast Sri Lanka until arrival of the Europeans on the island in the sixteenth century CE. Portuguese traders reached Sri Lanka by 1505 CE and the Jaffna kingdom came to the attention of Portuguese due to its presence as a logistical and strategic base for accessing the interior ruled by the Kandyan kingdom.[158] King Cankili I resisted contacts with the Portuguese and repelled Parava Catholics who were brought from India to the Mannar Island to take over the lucrative pearl fisheries from the Jaffna kings.[159][160] The wrested Mannar during the first invasion in 1560 and killed king Puvirasa Pandaram during the second expedition in 1591.[161] After the conflicts, the Portuguese secured the kingdom in 1619 from the unpopular Cankili II, who was helped by the Thanjavur Nayaks.[162][163] English sailor Robert Knox arrived in the island in 1669 and described the Tamil settlements in the An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon published in 1681.[164]

The Dutch captured the island later and ruled for more than a century. Following the 1795 invasion of the British and the Kandyan Wars, the island came to the control of the British in the early nineteenth century CE.[165] Upon arrival in June 1799, Hugh Cleghorn, the island's first British colonial secretary, wrote to the British government: "Two different nations from a very ancient period have divided between them the possession of the island. First the Sinhalese, inhabiting the interior in its Southern and Western parts, and secondly the Tamils who possess the Northern and Eastern districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religion, language, and manners."[166] Irrespective of the ethnic differences, the British imposed a unitary state structure in British Ceylon for better administration.[167] During the British colonial rule, Tamils held higher positions in the government and were favoured by the British for their qualification in English education. In the northern highlands, the lands of the Sinhalese were seized by the British and Indian Tamils were settled there as plantation workers.[168] Tamils who migrated in the nineteenth century CE to work on tea plantations were later termed as the Indian Tamils.[169]

Post Sri Lankan independence (1948–present)

[edit]

Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948 and after the colonial rule ended, ethnic tension rose between the Sinhalese, who constituted a majority, and the Tamils.[170] In 1956, the Sinhala Only Act designated Sinhala as the only official language of Sri Lanka, which forced many Tamils to resign as civil servants because they were not fluent in the language. The Tamils saw the act as linguistic, cultural and economic discrimination against them.[143] Anti-Tamil pogroms in 1956 and 1958 resulted in deaths of many Tamils and further escalated the conflict.[171][172][173] More than a million Indian Tamil plantation workers were made stateless after Sri Lanka refused citizenship to them. In 1964, the Sri Lankan and Indian governments entered into an agreement, based on which, about 300,000 would be granted Sri Lankan citizenship and about 975,000 Tamils would be repatriated to India over a period of fifteen years.[170][174]

A new Constitution enacted in the 1970s further discriminated against the Tamils and various state-sponsored schemes led Sinhalese settlers into Tamil populated areas. The 1977 anti-Tamil pogrom was followed by a crackdown against the Tamils, which curtailed their rights. Following the declaration of state of emergency in 1981, state-backed Sinhalese mobs turned on Tamils, which led many Tamils to leave the country as refugees resulting in an exodus more than half a million to India and other countries.[170] By the 1970s, initial non-violent political struggle for an independent Tamil state in the north and east of Sri Lanka, developed into a violent secessionist insurgency.[175][176] This led to the bloody Sri Lankan Civil War for more than three decades.[177][178] The conflict resulted in the deaths of at least 100,000 Tamils in the island and led to the flight of over 800,000 refugees.[179][180][181][182] The war ended after the Sri Lankan military offensive in 2009.[183] Since the end of the civil war, the Sri Lankan state has been subject to much global criticism for violating human rights as a result of committing war crimes through bombing civilian targets, usage of heavy weaponry, the abduction and massacres of Sri Lankan Tamils and sexual violence.[184][185][186][187]

Geographic distribution

[edit]India

[edit]

As per the 2011 Census, there were 69 million Tamil speakers, constituting about 5.7% of the Indian population. Tamils formed the majority in the South Indian state of Tamil Nadu (63.8 million) and the union territory of Puducherry (1.1 million).[2] There were also significant Tamil population in other states of India such as Karnataka (2.1 million), Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (0.7 million), Maharashtra (0.5 million), and Kerala (0.5 million).[188]

Sri Lanka

[edit]Tamils in Sri Lanka are classified into two ethnic groups by the Sri Lankan government: Sri Lankan Tamils, also known as Eelam Tamils, and Indian Origin Tamils, who accounted for 11.2%, and 4.1% of the country's population, respectively, in 2011.[4] The Sri Lankan Tamils (or Ceylon Tamils) are the descendants of the Tamils of the old Jaffna Kingdom and east coast chieftainships called Vannimais. The Indian Tamils (or Hill Country Tamils) are descendants of laborers who migrated from Tamil Nadu to Sri Lanka in the 19th century to work on tea plantations.[169] Most Sri Lankan Tamils live in the Northern and Eastern provinces and around Colombo, whereas most Indian Tamils live in the central highlands.[189] Historically, both the Tamil ethnic groups have identified themselves as separate communities, although there has been a greater sense of unity since the 1980s.[190]

There also exists a significant Tamil Muslim population in Sri Lanka. However, they are listed as a separate entity under the Moors by the government.[191][189] However, genealogical evidence suggests that most of the Sri Lankan Moor community are of Tamil ethnicity, and that the majority of their ancestors were also Tamils who had lived in the country for generations, and had converted to Islam from other faiths.[5][6]

Tamil diaspora

[edit]

Significant emigration from Indian subcontinent began in the late 18th century, when the Tamils went as indentured labourers and established businesses in other territories under the control of the British empire such as Malaya, Burma, South Africa, Fiji, Mauritius, and the Caribbean.[192] The descendants of these Tamils continued to live in these countries, and practice their original culture, tradition and language. They form significant proportion of the population in Malaysia (7%) and Singapore (5%).[11] A significant population also exists in South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji, as well as other regions such as the Southeast Asia and the Caribbean.[193] However, subsequent generations might not speak the language as a mother tongue, but instead as a second or third language.[194]

There is a small Tamil community in Pakistan, notably settled since the partition in 1947.[195] Since the 20th century, Tamils have migrated to other regions such as Middle East and the Western World for employment.[193][196][197] A large emigration of Sri Lankan Tamils began in the 1980s, as they sought to escape the ethnic conflict there.[170] The largest concentration of Eelam Tamils outside Sri Lanka is found in Canada.[198]

Culture

[edit]Language

[edit]

Tamil people speak Tamil, which belongs to the Dravidian languages and is one of the oldest classical languages.[199][200][201] According to epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan, the rudimentary Tamil Brahmi script originated in South India in the 3rd century BCE.[145][202] Though the old Tamil preserved features of Proto-Dravidian language,[203] modern-day spoken Tamil uses loanwords from other languages such as English.[204][205] The existent Tamil grammar is largely based on the grammar book Naṉṉūl which incorporates facets from the old Tamil literary work Tolkāppiyam.[206] Since the later part of the 19th century, Tamils made the language as a key part of the Tamil identity and the language is personified in the form of Tamil̲taay ("Tamil mother").[207] Various varieties of Tamil is spoken by the Tamils across regions such as Madras Bashai, Kongu Tamil, Madurai Tamil, Nellai Tamil, Kumari Tamil and various Sri Lankan Tamil dialects such as Batticaloa Tamil, Jaffna Tamil and Negombo Tamil in Sri Lanka.[208][209]

Literature

[edit]

Tamil literature is of considerable antiquity compared to the contemporary literature from other Indian languages and represents one of the oldest bodies of literature in South Asia.[210][211] The earliest epigraphic records have been dated to around the 3rd century BCE.[212] Early Tamil literature was composed in three successive poetic assemblies known as Tamil Sangams, the earliest of which destroyed by floods.[213][214][215] The Sangam literature was broadly classified into three divisions: iyal (poetry), isai (music) and nadagam (drama).[216][217] The early Tamil literature was compiled and classified into two categories: Patinenmelkanakku ("Eighteen Greater Texts") consisting of the Ettuttokai ("Eight Anthologies") and the Pattuppattu ("Ten Idylls"), and the Patinenkilkanakku ("Eighteen Lesser Texts").[218][219]

The Tamil literature that followed in the next 300 years after the Sangam period is generally called the "post-Sangam" literature which included the Five Great Epics.[215][219][220][221] Another book of the post Sangam era is the Tirukkural, a book on ethics, by Thiruvalluvar.[222] In the beginning of the Middle Ages, Vaishnava and Saiva literature became prominent following the Bhakti movement in 7th century CE with hymns composed by Alwars and Nayanmars.[223][224][225] Notable work from the post-Bhakti period included Ramavataram by Kambar in 12th century CE and Tiruppugal by Arunagirinathar in 15th century CE.[226][227] In 1578, the Portuguese published a Tamil book in old Tamil script named Thambiraan Vanakkam, thus making Tamil the first Indian language to be printed and published.[228] Tamil Lexicon, published by the University of Madras between 1924 and 1939, was amongst the first comprehensive dictionaries published in the language.[229][230] The 19th century gave rise to Tamil Renaissance and writings and poems by authors such as Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, U.V.Swaminatha Iyer, Damodaram Pillai, V. Kanakasabhai and others.[231][232][233] During the Indian Independence Movement, many Tamil poets and writers sought to provoke national spirit, notably Bharathiar and Bharathidasan.[234][235]

Art and architecture

[edit]According to Tamil literature, there are 64 art forms called aayakalaigal.[236][237] The art is classified into two broad categories: kavin kalaigal (beautiful art forms) which include architecture, sculpture, painting and poetry and nun kalaigal (fine art forms) which include dance, music and drama.[238]

Architecture

[edit]

Dravidian architecture is the distinct style of architecture of the Tamils. The large gopurams, which are monumental ornate towers at the entrance of the temples form a prominent feature of Hindu temples of the Dravidian style.[239][240][241][242] They are topped by kalasams (finials) and function as gateways through the walls that surround the temple complex.[243] There are a number of early rock-cut cave-temples established by the various Tamil kingdoms.[244][245][246] The Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram, built by the Pallavas in the 7th and 8th centuries has more than forty rock-cut temples, monoliths and rock reliefs.[62][247][248] The Pallavas, who built the group of monuments in Mahabalipuram and Kanchipuram, were one of the earliest patronisers of the Dravidian architectural style.[62][249] These gateways became regular features in the Cholas and the Pandya architecture, was later expanded by the Vijayanagara and the Nayaks and spread to other parts such as Sri Lanka.[250][251][252] There are more than 34,000 temples in Tamil Nadu built across various periods some of which are several centuries old.[253] The influence of Tamil culture had led to the construction of various temples outside India by the Tamil dispora.[254][255] The Mugal influence in medieval times and the British influence later gave rise to a blend of Hindu, Islamic and Gothic Revival styles, resulting in the distinct Indo-Saracenic architecture with several institutions during the British era following the style.[256][257][258] By the early 20th century, the Art Deco made its entry upon in the urban landscape.[259] In the later part of the century, the architecture witnessed a rise in the modern concrete buildings.[260][261]

Sculpture and paintings

[edit]

Tamil sculpture ranges from stone sculptures in temples, to detailed bronze icons.[263] The bronze statues of the Cholas are considered to be one of the greatest contributions of Tamil art.[264] Models made of a special mixture of beeswax and sal tree resin were encased in clay and fired to melt the wax leaving a hollow mould, which would then be filled with molten metal and cooled to produce bronze statues.[265] Tamil paintings are usually centered around natural, religious or aesthetic themes.[266] Sittanavasal is a rock-cut monastery and temple attributed to Pandyas and Pallavas which consist of frescoes and murals from the 7th century CE, painted with vegetable and mineral dyes in over a thin wet surface of lime plaster.[267][268][269] Similar murals are found in temple walls, the most notable examples are the murals on the Ranganathaswamy Temple at Srirangam and the Brihadeeswarar temple at Thanjavur.[270][271][272] One of the major forms of Tamil painting is Thanjavur painting, which originated in the 16th century CE where a base made of cloth and coated with zinc oxide is painted using dyes and then decorated with semi-precious stones, as well as silver or gold threads.[273][274]

Music

[edit]

The ancient Tamil country had its own system of music called Tamil Pannisai.[275] Sangam literature such as the Silappatikaram from 2nd century CE describes music notes and instruments.[276][277] A Pallava inscription dated to the 7th century CE has one of the earliest surviving examples of Indian music in notation.[278][279] The Pallava inscriptions from the period describe the playing of string instrument veena as a form of exercise for the fingers and the practice of singing musical hymns (Thirupadigam) in temples. From the 9th century CE, Shaivite hymns Thevaram and Vaishnavite hymns (Tiruvaymoli) were sung along with playing of musical instruments. Carnatic music originated later which included rhythmic and structured music by composers such Thyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Shyama Shastri.[280][281] Villu Paatu is an ancient form of musical story-telling method where narration is interspersed with music played from a string bow and accompanying instruments.[282][283] Gaana, a combination of various folk musics is sung mainly in Chennai.[284]

There are many traditional instruments from the region dating back to the Sangam period such as parai,[285] tharai,[286] yazh,[287] and murasu.[288][289] Nadaswaram, a reed instrument that is often accompanied by the thavil, a type of drum instrument are the major musical instruments used in temples and weddings.[290] Melam is from a group of percussion instruments from the ancient Tamilakam which are played during events and functions.[291][292][293]

Performance arts

[edit]

Bharatanatyam is a major genre of Indian classical dance that originated from the Tamils.[294][295][296][297] It is one of the oldest classical dance forms of India.[298][299] There are many folk dance forms that originated and are practiced in the region. Major folk dance forms include Karakattam and Kavadiattam which involve dancers balancing decorated pot(s) on their heads and arch shaped wooden sticks on their shoulders respectively while making dance movements with the body.[300][301][302][303] Kolattam and Kummi are usually performed by women while singing songs.[304][305][306][307] In dances like Mayilattam, Puravaiattam, and Puliyattam, dancers dress like peacocks, horses and tigers respectively and headdresses perform movements imitating the animals.[308][309][310][311][312][313] Other traditional dance forms include the war dance Oyilattam and Paraiattam.[314][315][316]

Koothu is a form of street theater that consists of a play performance which consists of dance along with music, narration and singing.[317][318] Bommalattam is a type of puppetry that uses various doll marionettes manipulated by rods and strings attached to them.[319][320][321]

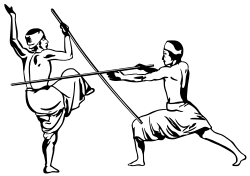

Martial arts

[edit]

Silambam is a martial art involving the usage of a long staff of about 168 cm (66 in) in length, often made of wood such as bamboo.[322][323] It was used for self-defense and to ward off animals and later evolved into a martial art and dance form.[324] Adimurai (or Kuttu varisai) is a martial art specializing in empty-hand techniques and application on vital points of the body.[325][326][327] Varma kalai is a Tamil traditional art of vital points which combines alternative medicine and martial arts, attributed to sage Agastiyar and might form part of the training of other martial arts such as silambattam, adimurai or kalari.[328] Malyutham is the traditional form of combat-wrestling.[325][329]

Tamil martial arts uses various types of weapons such as valari (iron sickle), maduvu (deer horns), vaal (sword) and kedayam (shield), surul vaal (curling blade), itti or vel (spear), savuku (whip), kattari (fist blade), aruval (machete), silambam (bamboo staff), kuttu katai (spiked knuckleduster), kathi (dagger), vil ambu (bow and arrow), tantayutam (mace), soolam (trident), valari (boomerang), chakaram (discus) and theepandam (flaming baton).[330][331] Wootz steel used to make weapons, originated in the mid-1st millennium BCE in South India.[332][333][334][335] Locals in Sri Lanka adopted the production methods of creating wootz steel from the Cheras and the later trade introduced it to other parts of the world.[336][337] Since the early Sangam age, war was regarded as an honourable sacrifice and fallen heroes and kings were worshipped with hero stones and heroic martyrdom was glorified in ancient Tamil literature.[338] Defeated kings committed Vatakkiruttal, a form of ritual suicide.[339]

Modern arts

[edit]The Tamil film industry nicknamed as Kollywood and is one of the largest industries of film production in India.[340][341] Independent Tamil film production have also originated outside India in Sri Lanka, Singapore, Canada, and western Europe.[342] The concept of "Tent Cinema" was introduced in the early 1900s, in which a tent was erected on a stretch of open land close to a town or village to screen the films.[343][344][345] The first silent film in South India was produced in Tamil in 1916 and the first Tamil talkie film was Kalidas, which released on 31 October 1931, barely seven months after the release of India's first talking picture Alam Ara.[346][347]

Clothing

[edit]

Ancient literature and epigraphical records describe the various types of dresses worn by Tamil people.[349][350] Tamil women traditionally wear a sari, a garment that consists of a drape varying from 4.6 m (15 ft) to 8.2 m (27 ft) in length and 0.61 m (2 ft) to 1.2 m (4 ft) in breadth that is typically wrapped around the waist, with one end draped over the shoulder, baring the midriff.[351][352][353] Women wear colourful silk sarees on traditional occasions.[354][355] Young girls wear a long skirt called pavaadai along with a shorter length sari called dhavani.[350] The men wear a dhoti, a 1.9 m (6 ft 3 in) long, white rectangular piece of non-stitched cloth often bordered in brightly coloured stripes which is usually wrapped around the waist and the legs and knotted at the waist.[350][353][356] A colourful lungi with typical batik patterns is the most common form of male attire in the countryside.[350][357] People in urban areas generally wear tailored clothing, and western dress is popular. Western-style school uniforms are worn by both boys and girls in schools, even in rural areas.[357]

Calendar

[edit]The Tamil calendar is a sidereal solar calendar.[358] The Tamil Panchangam is based on the same and is generally used in contemporary times to check auspicious times for cultural and religious events.[359] The calendar follows a 60-year cycle.[360] There are 12 months in a year starting with Chithirai when the Sun enters the first Rāśi and the number of days in a month varies between 29 and 32.[361] The new year starts following the March equinox in the middle of April.[362] The days of week (kiḻamai) in the Tamil calendar relate to the celestial bodies in the Solar System: Sun, Moon, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn, in that order.[363]

Food and hospitality

[edit]

Hospitality is a major feature of Tamil culture.[364] It was considered as a social obligation and offering food to guests was regarded as one of the highest virtues.[365][366] Rice is the diet staple and is served with sambar, rasam, and poriyal as a part of a Tamil meal.[367][368] Bananas find mention in the Sangam literature and the traditional way of eating a meal involves having the food served on a banana leaf, which is discarded after the meal. Eating on banana leaves imparts a unique flavor to the food, and is considered healthy.[369][370][371] Food is usually eaten seated on the floor and the finger tips of the right hand is used to take the food to the mouth.[372]

There are regional sub-varieties namely Chettinadu, Kongunadu, Nanjilnadu, Pandiyanadu and Sri Lankan Tamil cuisines.[373][374] There are both vegetarian and meat dishes with fish traditionally consumed across the coast and other meat preferred in the interiors. The Chettinadu cuisine is popular for its meat based dishes and generous usage of spices.[375] The Kongunadu cuisine uses less spices and are generally cooked fresh. It uses coconut, sesame seeds, groundnut, and turmeric to go with various cereals and pulses grown in the region.[375][376] Nanjilnadu cuisine is milder and is usually based on fish and vegetables.[375] Sri Lankan Tamil cuisine uses gingelly oil and jaggery along with coconut and spices, which differentiates it from the other culinary traditions in the island.[374] Biryani is a popular dish with several different versions prepared across various regions.[376] Idli, and dosa are popular breakfast dishes and other dishes cooked by to the Tamil people include upma,[377] idiappam,[378] pongal,[379] paniyaram,[380] and parotta.[381]

Medicine

[edit]Siddha medicine is a form of traditional medicine originating from the Tamils and is one of the oldest systems of medicine in India.[382] The word literally means perfection in Tamil and the system focuses on wholesome treatment based on various factors. As per Tamil tradition, the knowledge of Siddha medicine came from Shiva, which was passed on to 18 holy men known as Siddhar led by Agastya. The knowledge was then passed on orally and through palm leaf manuscripts to the later generations.[383] Siddha practitioners believe that all objects including the human body is composed of five basic elements – earth, water, fire, air, sky which are present in food and other compounds, which is used as the basis for the drugs and other therapies.[384]

Festivals

[edit]Pongal is a major and multi-day harvest festival celebrated by Tamils in the month of Thai according to the Tamil solar calendar (usually falls on 14 or 15 January).[386][387][388][389] Puthandu is known as Tamil New Year which marks the first day of year on the Tamil calendar and falls on in April every year on the Gregorian calendar.[390] Other major festivals include Karthikai Deepam,[391][392] Thaipusam,[393][394] Panguni Uthiram,[395][396] and Vaikasi Visakam.[397] Aadi Perukku is a Tamil cultural festival celebrated in the Tamil month of Adi and the worship of Amman and Ayyanar deities are organized during the month in temples across Tamil Nadu with much fanfare.[293] Other festivals celebrated include Ganesh Chaturthi, Navarathri, Deepavali, Eid al-Fitr and Christmas.[398][399][400]

Sports

[edit]

Jallikattu is a traditional event held during the period attracting huge crowds in which a bull is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull's back with both arms and hang on to it while the bull attempts to escape.[401][402] It has been practised since Sangam period with the aim of keeping people fit. Proficiency in the sport was considered a virtue while untamable bulls were held as a pride of the owner.[403][404] Kabaddi is a traditional contact sport that originated from the Tamils.[405][406] Chess is a popular board game which originated as Sathurangam in the 7th century CE.[407] Traditional games like Pallanguzhi,[408] Uriyadi,[409] Gillidanda,[410] Dhaayam are played across the region.[411] In modern times, Cricket is the most popular sport.[412]

Religion

[edit]

As per the Sangam literature, the Sangam landscape was classified into five categories known as thinais, which were associated with a Hindu deity: Murugan in kurinji (hills), Thirumal in mullai (forests), Indiran in marutham (plains), Varunan in the neithal (coasts) and Kotravai in palai (desert).[413] Thirumal is indicated as a deity during the Sangam era, who was regarded as Paramporul ("the suprement one") and is also known as Māyavan, Māmiyon, Netiyōn, and Māl in various Sangam literature.[414][415] While Shiva worship existed in the Shaivite culture as a part of the Tamil pantheon, Murugan became regarded as the Tamil kadavul ("God of the Tamils").[416][417][418] In Tamil tradition, Murugan is the youngest son of Shiva and Parvati and Pillayar is regarded as the eldest son, who is venerated as the Mudanmudar kadavul ("foremost god").[419]

The cult of the mother goddess is treated as an indication of a society which venerated femininity. The worship of Amman, also called Mariamman, is thought to have been derived from an ancient mother goddess, and is also very common.[420][421][422] Kannagi, the heroine of the Cilappatikaram is worshipped as a goddess by many Tamils, particularly in Sri Lanka.[423] In the Sangam literature, there is a description of the rites performed by the priestesses in temples.[424] Among the ancient Tamils, the practice of erecting memorial stones (natukal) was prevalent and it continued till the Middle ages.[425] It was customary for people who sought victory in war to worship these hero stones to bless them with victory.[426] In rural areas, local deities called Aiyyan̲ār (also known as Karuppan, Karrupasami, Muniandi), are worshipped who are thought to protect the villages from harm.[420][427][428] Their worship probably emanated from the hero stone worship and appears to be the surviving remnants of an ancient Tamil tradition.[429] Idol worship forms a part of the Tamil Hindu culture similar to the Hindu traditions.[430][431]

During the Sangam period, Ashivakam, Jainism and Buddhism also had a significant following.[432] Jainism existed from the Sangam period with inscriptions and drip-ledges from 1st century BCE to 6th century CE describing the same.[433][434] The Kalabhra dynasty, who were patrons of Jainism, ruled over the ancient Tamil country in the 3rd–7th century CE.[435][436] Buddhism had an influence in Tamil Nadu before the later Middle Ages with ancient texts referring to a Vihāra in Nākappaṭṭinam from the time of Ashoka in 3rd century BCE and Buddhist relics from 4th century CE found in Kaveripattinam.[437][438][439] Around the 7th century CE, the Pandyas and Pallavas, who patronized Buddhism and Jainism, became patrons of Hinduism following the revival of Saivism and Vaishnavism during the Bhakti movement led by Alwars and Nayanmars.[59][223]

The Christian apostle, St. Thomas, is believed to have preached Christianity to the Tamils between 52 and 70 CE.[440] Rowthers were Tamils who were converted to Islam by the Turkish preacher Nathar Shah in the tenth century CE and follow the Hanafi school.[441][442][443][444] Other Muslim clans such as Marakkayar, Labbai, and Kayalar originated as a result of the trade with the Arab world.[445][446][447] Majority of the Tamil Muslims speak Tamil rather than Urdu, which is spoken by Muslims in other parts of the Indian subcontinent.[448][449][450] Mercantile groups introduced Cholapauttam, a syncretic form of Buddhism and Shaivism in northern Sri Lanka and Southern India. The religion lost its importance in the 14th century when conditions changed for the benefit of Sinhala and Pali traditions.[451]

As of the 21st century, majority of the Tamils are adherents of Hinduism.[452] The migration of Tamils to other countries resulted in new Hindu temples being constructed in places with significant population of Tamil people and people of Tamil origin, and countries with significant Tamil migrants.[453] Sri Lankan Tamils predominantly worship Murugan with numerous temples existing throughout the island.[454][455] There are also followers of Ayyavazhi in Tamil Nadu, mainly in the southern districts.[456] Atheist, rationalist, and humanist philosophies are also adhered by sizeable minorities, as a result of Tamil cultural revivalism in the 20th century, and its antipathy to what it saw as Brahminical Hinduism.[457]

Notable people

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tamils in Sri Lanka are classified into three ethnicities by the Sri Lankan government, namely Sri Lankan Tamils, Indian Origin Tamils and Sri Lankan Moors who accounted for 11.2%, 4.1% and 9.3% respectively of the country's population in 2011.[4] Indian Origin Tamils were separately classified from the 1911 census onwards and the Sri Lankan government lists a substantial Tamil-speaking Muslim population under the distinct ethnicity of Moors. However, genealogical evidence suggests that most of the Sri Lankan Moor community are of Tamil ethnicity, and that the majority of their ancestors were also Tamils who had lived in the country for generations, and had converted to Islam from other faiths.[5][6]

- ^ Includes all speakers of the Tamil language including multi-generation individuals do not speak the language as a mother tongue, but instead as a second or third language.

- ^ Includes 88,000 primary Tamil speakers and 86,708 speakers of English language who speak Tamil as secondary language.

- ^ Tamil: தமிழர், romanized: Tamiḻar pronounced [t̪amiɻaɾ] in the singular or தமிழர்கள், Tamiḻarkaḷ [t̪amiɻaɾɡaɭ] in the plural

References

[edit]- ^ "Tamil". World data. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ a b Census of India 2011 - Language Atlas (PDF). Government of India (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Census of Population and Housing of Sri Lanka, 2012 – Table A3: Population by district, ethnic group and sex (PDF). Government of Sri Lanka (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ a b "A2: Population by ethnic group according to districts, 2012". Government of Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ a b Mohan, Vasundhara (1987). Identity Crisis of Sri Lankan Muslims. Delhi: Mittal Publications. pp. 9–14, 27–30, 67–74, 113–18.

- ^ a b "Analysis: Tamil-Muslim divide". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ Tamil at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ Jeyaraj, D.B.S. (31 August 2013), "Navaneetham Pillay The most famous South African Tamil of our times", Daily Mirror, Colombo, archived from the original on 21 October 2019, retrieved 16 September 2025

- ^ "Commuting Times, Median Rents and Language other than English Use". Government of United States (Press release). 7 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 October 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Knowledge of languages by age and gender: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts. Government of Canada (Report). 17 August 2022. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ a b Singapore Census of Population 2020, Statistical Release 1: Demographic Characteristics, Education, Language and Religion. Government of Singapore (Report). Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Wood, Michael (2 August 2007). A South Indian Journey: The Smile of Murugan. Penguin UK. pp. x, xiii, xvi. ISBN 978-0-14193-527-0. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Tamil, n. and adj". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Frank Rennie, Robin Mason, ed. (December 2008). Bhutan: Ways of Knowing. Information Age Publishing. p. 247. ISBN 978-1-60752-824-1. Archived from the original on 18 September 2023. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

Tamilians, a group living in the southern state of Tamil Nadu.

- ^ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The smile of Murugan: on Tamil literature of South India. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-3-447-01582-0.

- ^ Zvelebil 1992, p. 10-16.

- ^ Southworth, Franklin (1998). "On the Origin of the word tamiz". International Journal of Dravidial Linguistics. 27 (1): 129–32.

- ^ Alain Daniélou (11 February 2003). A Brief History of India. Inner Traditions. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3.

- ^ Rama Shankar Tripathi (1942). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-8-12080-018-2.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ K. P. Jayaswal; R. D. Banerji (1920). Epigraphia Indica Volume XX. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 86–89.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Mabel Haynes Bode (1909). The Pali Literature of Burma. p. 39.

- ^ Dines Andersen (1992). The Jātaka: together with its commentary, being tales of the anterior births of Gotama Buddha. University of California. p. 66.

- ^ a b Tomás Morales y Durán (2020). Jesus of Nazareth: The Deep State of Rome. Amazon Digital Services. p. 27. ISBN 979-8-56272-624-7.

- ^ Lal, Mohan, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot. Sahitya Akademi. p. 4283.

- ^ "Science News : Archaeology – Anthropology : Sharp stones found in India signal surprisingly early toolmaking advances". 31 January 2018. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Very old, very sophisticated tools found in India. The question is: Who made them?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ "Skeletons dating back 3,800 years throw light on evolution". The Times of India. 1 January 2006. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ^ John, Vino (27 January 2006). "Reading the past in a more inclusive way: Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

But Indian/south Indian history/archaeology has pushed the date back to 1500 B.C., and in Sri Lanka, there are definitely good radiometric dates coming from Anuradhapura that the non-Brahmi symbol-bearing black and red ware occur at least around 900 B.C. or 1000 B.C.

- ^ Sastri 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Codrington, K. De B. (October 1930). "Indian Cairn- and Urn-Burials". Man. 30 (30): 190–196. doi:10.2307/2790468. JSTOR 2790468.

It is necessary to draw attention to certain passages in early Tamil literature which throw a great deal of light upon this strange burial ceremonial ...

- ^ T, Saravanan (22 February 2018). "How a recent archaeological discovery throws light on the history of Tamil script". Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ "the eternal harappan script". Open magazine. 27 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^ Shekar, Anjana (21 August 2020). "Keezhadi sixth phase: What do the findings so far tell us?". The News Minute. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "A rare inscription". Frontline. 1 July 2009. Archived from the original on 22 September 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Artifacts unearthed at Keeladi to find a special place in museum". The Hindu. 19 February 2023. Archived from the original on 14 November 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Jesudasan, Dennis S. (20 September 2019). "Keezhadi excavations: Sangam era older than previously thought, finds study". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Joshi, Anjali (2017). Social and Cultural History of Ancient India. Online Gatha. pp. 123–136. ISBN 978-9-386-35269-9.

- ^ "Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 24 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ A. Kiruṭṭin̲an̲ (2000). Tamil culture: religion, culture, and literature. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. p. 17.

- ^ Sastri 2002, p. 109.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 425.

- ^ "The Edicts of King Ashoka". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

Everywhere within Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi's domain, and among the people beyond the borders, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Satyaputras, the Keralaputras, as far as Tamraparni

- ^ "Hathigumpha Inscription". Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XX (1929–1930). Delhi, 1933, pp. 86–89. Missouri Southern State University. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ P.J. Cherian (ed.). Perspectives on Kerala History. Kerala Council for Historical Research. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2006.

There were three levels of redistribution corresponding to the three categories of chieftains, namely: the Ventar, Velir and Kilar in descending order. Ventar were the chieftains of the three major lineages, viz Cera, Cola and Pandya. Velir were mostly hill chieftains, while Kilar were the headmen of settlements ...

- ^ Sivathamby, K. (December 1974). "Early South Indian Society and Economy: The Tinai Concept". Social Scientist. 3 (5): 20–37. doi:10.2307/3516448. JSTOR 3516448.

Those who ruled over small territories were called Kurunilamannar. The area ruled by such a small ruler usually corresponded to a geographical unit. In Purananuru a number of such chieftains are mentioned;..

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1991). "Comments on the Tolkappiyam Theory of Literature". Archiv Orientální. 59: 345–359.

- ^ "Poem: Purananuru - Part 224 by George L. III Hart". Poetrynook. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Poem: Purananuru - Part 231 by George L. III Hart". Poetrynook. Archived from the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. (September 1988). "The Role of Peasants in the Early History of Tamilakam in South India". Social Scientist. 16 (9): 17–34. doi:10.2307/3517170. JSTOR 3517170.

- ^ "Grand Anaicut". Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2006.

- ^ William Dalrymple (23 September 2023). "The ancient history behind the maritime trade route between India and Europe". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "On the Roman Trail". The Hindu. 21 January 2008. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- ^ Sastri 2002, p. 125-127.

- ^ "The Medieval Spice Trade and the Diffusion of the Chile". Gastronomica. 7. 26 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ W.H. Schoff (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ Chakrabarty, D.K. (2010). The Geopolitical Orbits of Ancient India: The Geographical Frames of the Ancient Indian Dynasties. Oxford. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-199-08832-4. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ T.V. Mahalingam (1981). Proceedings of the Second Annual Conference. South Indian History Congress. pp. 28–34.

- ^ a b Sastri 2002, p. 333.

- ^ Hirsh, Marilyn (1987). "Mahendravarman I Pallava: Artist and Patron of Mamallapuram". Artibus Asiae. 48 (1/2): 109–130. doi:10.2307/3249854. JSTOR 3249854.

- ^ Francis, Emmanuel (28 October 2021). "Pallavas". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1002/9781119399919.eahaa00499. ISBN 978-1-119-39991-9. S2CID 240189630. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "Group of Monuments at Mahabalipuram". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Sastri 2002, p. 135-140.

- ^ "Pandya dynasty". Britannica. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Freeman, Rich (February 1998). "Rubies and Coral: The Lapidary Crafting of Language in Kerala". The Journal of Asian Studies. 57 (1): 38–65. doi:10.2307/2659023. JSTOR 2659023. S2CID 162294036.

- ^ Subrahmanian, N. (1993). Social and cultural history of Tamilnad. Ennes. p. 209.

- ^ Paniker, K. Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-8-12600-365-5.

- ^ Jouveau-Dubreuil, Gabriel (1995). "The Pallavas". Asian Educational Services: 83.

- ^ Biddulph, Charles Hubert (1964). Coins of the Cholas. Numismatic Society of India. p. 34.

- ^ John Man (1999). Atlas of the year 1000. Harvard University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-674-54187-0.

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 590.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2003) [2002]. The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. Penguin Books. pp. 364–365. ISBN 978-0-143-02989-2. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904). The Early History of India. Clarendon Press. pp. 336–358. ISBN 978-8-17156-618-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Srivastava, Balram (1973). Rajendra Chola. National Book Trust. p. 80.

The mission which Rajendra sent to China was essentially a trade mission, ...

- ^ Curtin, Philip D. (1984). Cross-Cultural Trade in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-521-26931-5.

- ^ "Great Living Chola Temples". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ John Allan; Wolseley Haig; Henry Dodwell (1934). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 191.

- ^ Sen 1999, p. 485.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay, eds. (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Nilakanta Sastri (1955). The Cōḷas. University of Madras. p. 301. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- ^ Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (1921). South India and her Muhammadan Invaders. Oxford University Press. p. 44.

- ^ S. Jeyaseela Stephen, ed. (2008). The Land, Peasantry, and Peasant Life in India New Direction, Renewed Debate. Manak Publications. p. 87.

- ^ Sen 1999, p. 487.

- ^ Sen 1999, p. 459.

- ^ Nick Collins (2024). The Millennium Maritime Trade Revolution, 700–1700: How Asia Lost Maritime Supremacy. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-39906-016-5.

- ^ "Meenakshi Amman Temple". Britannica. 30 November 2023. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot (2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-198-03123-9.

- ^ Kenneth McPherson · (2012). 'How Best Do We Survive?' A Modern Political History of the Tamil Muslims. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-13619-833-5. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Medieval India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 82. ISBN 978-8-17141-683-7. Archived from the original on 26 May 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Gilmartin, David; Lawrence, Bruce B. (2000). Beyond Turk and Hindu: Rethinking Religious Identities in Islamicate South Asia. University Press of Florida. pp. 300–306, 321–322. ISBN 978-0-813-03099-9.

- ^ Srivastava, Kanhaiya L (1980). The position of Hindus under the Delhi Sultanate, 1206–1526. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 202. ISBN 978-8-12150-224-5.

- ^ Burton Stein (1990). The New Cambridge History of India Vijayanagara Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 57.

- ^ Ē. Kē Cēṣāttiri (1998). Sri Brihadisvara, the Great Temple of Thanjavur. Nile Books. p. 24.

- ^ P. K. S. Raja (1966). Mediaeval Kerala. Navakerala Co-op Publishing House. p. 47.

- ^ "Rama Raya (1484–1565): élite mobility in a Persianized world". A Social History of the Deccan, 1300–1761. 2005. pp. 78–104. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521254847.006. ISBN 978-0-52125-484-7.

- ^ Eugene F. Irschick (1969). Politics and Social Conflict in South India. University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-520-00596-9.

- ^ Balendu Sekaram, Kandavalli (1975). The Nayaks of Madurai. Andhra Pradesh Sahithya Akademi. OCLC 4910527.

- ^ Heather Elgood (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 162.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700–1900 (Reprinted ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-52189-103-5.

- ^ Naravane, M.S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company. A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 151, 154–158. ISBN 978-8-131-30034-3.

- ^ Ramaswami, N. S. (1984). Political history of Carnatic under the Nawabs. Abhinav Publications. pp. 43–79. ISBN 978-0-836-41262-8.

- ^ Tony Jaques (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Greenwood. pp. 1034–1035. ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Subramanian, K. R. (1928). The Maratha Rajas of Tanjore. Madras: K. R. Subramanian. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Bhosle, Pratap Sinh Serfoji Raje (2017). Contributions of Thanjavur Maratha Kings. Notion press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-948-23095-7.

- ^ "Rhythms of the Portuguese presence in the Bay of Bengal". Indian Institute of Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Origin of the Name Madras". Corporation of Madras. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "Danish flavour". Frontline. India. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Rao, Velcheru Narayana; Shulman, David; Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1998). Symbols of substance : court and state in Nayaka period Tamilnadu. Oxford University Press, Delhi. p. xix, 349 p., [16] p. of plates : ill., maps; 22 cm. ISBN 978-0-195-64399-2.

- ^ Thilakavathy, M.; Maya, R. K. (5 June 2019). Facets of Contemporary history. MJP Publisher. p. 583. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Frykenberg, Robert Eric (26 June 2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-198-26377-7. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Keay, John (1993). The Honourable Company: A History of the English East India Company. Harper Collins. pp. 31–36.

- ^ S., Muthiah (21 November 2010). "Madras Miscellany: When Pondy was wasted". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 May 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2010). A global chronology of conflict. ABC—CLIO. p. 756. ISBN 978-1-851-09667-1. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Seven Years' War: Battle of Wandiwash". History Net: Where History Comes Alive – World & US History Online. 21 August 2006. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Velu Nachiyar, India's Joan of Arc" (Press release). Government of India. Archived from the original on 27 July 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ Yang, Anand A (2007). "Bandits and Kings:Moral Authority and Resistance in Early Colonial India". The Journal of Asian Studies. 66 (4): 881–896. doi:10.1017/S0021911807001234. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 20203235.

- ^ Caldwell, Robert (1881). A Political and General History of the District of Tinnevelly, in the Presidency of Madras. Government Press. pp. 195–222.

- ^ Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of Modern India:1707 A.D. to 2000 A.D. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 94. ISBN 978-8-126-90085-5. Archived from the original on 3 June 2024. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Madras Presidency". Britannica. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- ^ Naravane, M. S. (2014). Battles of the Honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj. New Delhi: A.P.H. Publishing Corporation. pp. 172–181. ISBN 978-8-131-30034-3.

- ^ "July, 1806 Vellore". Outlook. 17 July 2006. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Pletcher, Kenneth. "Vellore Mutiny". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Adcock, C.S. (2013). The Limits of Tolerance: Indian Secularism and the Politics of Religious Freedom. Oxford University Press. pp. 23–25. ISBN 978-0-199-99543-1.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (22 August 2013). "The great famine of Madras and the men who made it". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Sitaramayya, Pattabhi (1935). The History of the Indian National Congress. Working Committee of the Congress. p. 11.

- ^ Bevir, Mark (2003). "Theosophy and the Origins of the Indian National Congress". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 7 (1–3). University of California: 14–18. doi:10.1007/s11407-003-0005-4. S2CID 54542458. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

Theosophical Society provided the framework for action within which some of its Indian and British members worked to form the Indian National Congress.

- ^ "Subramania Bharati: The poet and the patriot". The Hindu. 9 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ "An inspiring saga of the Tamil diaspora's contribution to India's freedom struggle". The Hindu. 7 November 2023. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Bose, Sugata (2011). His Majesty's Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India's Struggle against Empire. Harvard University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-674-04754-9.

At least eighteen thousand civilians, mostly Tamils from southern India, enlisted in the Indian National Army.

- ^ Andhra State Act, 1953 (PDF). Madras Legislative Assembly. 14 September 1953. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ States Reorganisation Act, 1956 (PDF). Parliament of India. 14 September 1953. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ "Tracing the demand to rename Madras State as Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. 6 July 2023. Archived from the original on 28 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Sundari, S. (2007). Migrant women and urban labour market: concepts and case studies. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 105. ISBN 978-8-176-29966-4. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ V. Shoba (14 August 2011). "Chennai says it in Hindi". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Demography of Tamil Nadu. Government of India (Report). Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ Krishna, K.L. (September 2004). Economic Growth in Indian States (PDF) (Report). Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Vijitha Yapa. p. 129. ISBN 978-9-55809-592-8.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 53–54.

- ^ South Asia Bulletin: Volumes 7–8. University of California. 1987. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 129.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Subramanian, T.S. (27 January 2006). "Reading the past in a more inclusive way: Interview with Dr. Sudharshan Seneviratne". Frontline. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ a b Tambiah, Stanley Jeyaraja (1986). Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. I.B.Tauris. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85043-026-1.

- ^ Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna. p. 223.

- ^ a b Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy From The Earliest Times To The Sixth Century A. D. Harvard University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-67401-227-1.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 157.

- ^ de Silva 1997, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Mendis, G.C. Ceylon Today and Yesterday. Associated Newspapers of Ceylon. pp. 24–25.

- ^ Allen, C. (2017). Coromandel: A Personal History of South India. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-40870-540-7. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

A later chapter of the 'Great Chronicle' describes how the Chola prince Elara (Ellalan) of Thiruvarur invaded and captured the throne of Lanka in about 205 BCE but was later killed in battle by the Sinhala prince Dutugamunu in about 161

- ^ a b c Spencer, George W (1976). "The politics of plunder: The Cholas in eleventh century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3): 405–419. doi:10.2307/2053272. JSTOR 2053272. S2CID 154741845.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 214–215.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 76.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 100–102.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 102–04.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 104.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 121.

- ^ Indrapala 2007, p. 275.

- ^ Abeysinghe, Tikiri (1986). Jaffna Under the Portuguese. Lake House Investments. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-9-55552-000-3.

- ^ Kunaraca, Kantaiya (2003). The Jaffna Dynasty: Vijayakalingan to Narasinghan. Dynasty of Jaffna Kings' Historical Society. pp. 82–84. ISBN 978-9-55845-500-5.

- ^ Gnanaprakasar, S. (2020). A critical history of Jaffna: the Tamil era. Gyan. pp. 113–117. ISBN 978-8-12122-063-7.

- ^ de Silva 1997, p. 166.

- ^ Vriddhagirisan, V. (1942). The Nayaks of Tanjore. Annamalai University. p. 80. ISBN 978-8-12060-996-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ de Silva, Chandra (1972). The Portuguese in Ceylon, 1617–1638. University of London. p. 96. Archived from the original on 14 September 2024. Retrieved 14 September 2024.

- ^ Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. Robert Chiswell. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-40691-141-1. 2596825.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Christie, Nikki (2016). Britain: losing and gaining an empire, 1763–1914. Pearson Education. p. 53.

- ^ Ponnambalam, Satchi (1983). Sri Lanka: National Conflict and the Tamil Liberation Struggle. Tamil Information Centre. ISBN 978-0-86232-198-7.

- ^ Horowitz, Donald (2001). Ethnic Groups in Conflict. University of California Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-52092-631-8.

- ^ Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-59033-573-4.

- ^ a b de Silva 1997, pp. 177, 181.

- ^ a b c d "Tamils". Minority Rights. 16 October 2023. Archived from the original on 4 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.