Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

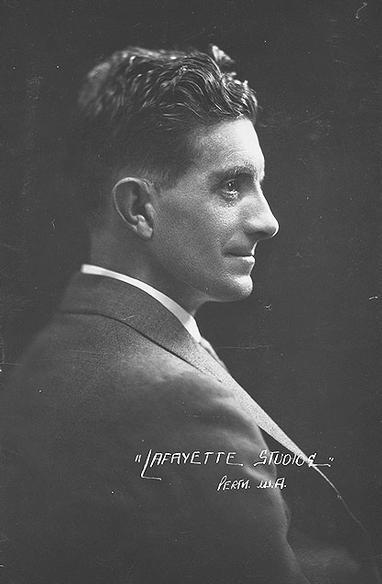

Arthur Upfield

View on Wikipedia

Arthur William Upfield (1 September 1890 – 12 February 1964) was an English-Australian writer, best known for his works of detective fiction featuring Detective Inspector Napoleon "Bony" Bonaparte of the Queensland Police Force, a mixed-race Indigenous Australian. His books were the basis for a 1970s Australian television series entitled Boney, as well as a 1990 telemovie and a 1992 spin-off TV series.

Key Information

Born in England, Upfield moved to Australia in 1911 and fought for the Australian military during the First World War. Following his war service, he travelled extensively throughout Australia, obtaining a knowledge of Australian Aboriginal culture that he would later use in his written works. In addition to writing detective fiction, Upfield was a member of the Australian Geological Society and was involved in numerous scientific expeditions.

In The Sands of Windee, a story about a "perfect murder", Upfield invented a method to destroy carefully all evidence of the crime. Upfield's "Windee method" was used in the Murchison Murders, and because Upfield had discussed the plot with friends, including the man accused of the murders, he was called to give evidence in court.[1] The episode is dramatised in the film 3 Acts of Murder, starring Robert Menzies.

Early life

[edit]The son of a draper, Upfield was born in Gosport, Hampshire, England, on 1 September 1890.[2] In 1911, after he did poorly in examinations towards becoming a real estate agent, Upfield's father sent him to Australia.[3]

With the outbreak of the First World War in the summer of 1914, he joined the First Australian Imperial Force on 23 August 1914.[4] He sailed from Brisbane on 24 September 1914 to Melbourne. At the time of sailing he had the rank of Driver and was with the Australian 1st Light Horse Brigade Train (5 Company ASC [Army Service Corps]).[5] In Melbourne he was at a camp for several weeks before sailing to Egypt.[6] He fought at Gallipoli and in France and married an Australian nurse, Ann Douglass, in Egypt in 1915. He was discharged in England on 15 October 1919. Before returning to Australia, Ann gave birth to their only child, James Arthur, born 8 February 1920.[7]

For most of the next 20 years he travelled throughout the outback, working at a number of jobs and learning about Aboriginal cultures. A contributor of an article 'Coming Down with Cattle' to the first edition of Walkabout magazine, he later used the knowledge and material he had gathered in his books.

Career

[edit]Upfield created the character of Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, based on a man known as "Tracker Leon", whom he said he had met in his travels. Leon was supposedly a half-caste employed as a tracker by the Queensland Police.[2] He was also said to have read Shakespeare and a biography of Napoleon, and to have received a university education. However, there is no evidence that any such person ever existed.[8] The novels featuring Bony, as the detective was also known, were far more successful than any other writings by Upfield.

Late in life Upfield became a member of the Australian Geological Society, involved in scientific expeditions.[7] He led a major expedition in 1948 to northern and western parts of Australia, including the Wolfe Creek Crater, which was a setting for his novel The Will of the Tribe published in 1962.[10]

After living at Bermagui, New South Wales, Upfield moved to Bowral.[9] Upfield died at Bowral on 12 February 1964.[9] His last work, The Lake Frome Monster, published in 1966, was completed by J.L. Price and Dorothy Stange.

In 1957, Jessica Hawke published a biography of the author entitled Follow My Dust!. It is generally held, however, that this was written by Upfield himself.[3]

Works

[edit]Upfield's novels were held in high regard by some fellow writers. In 1987, H. R. F. Keating included The Sands of Windee in his list of the 100 best crime and mystery books ever published.[2] J. B. Priestley wrote of Upfield: "If you like detective stories that are something more than puzzles, that have solid characters and backgrounds, that avoid familiar patterns of crime and detection, then Mr Upfield is your man."[2] His grandson, William Arthur Upfield holds his grandfather's copyright, and the trademark 'Bony', keeping the works in print.[citation needed]

The American mystery novelist Tony Hillerman praised Upfield's works. In his introduction to the posthumous 1984 reprint of Upfield's A Royal Abduction, he described the seduction in his youth of Upfield's descriptions of both the harsh outback areas, and "the people who somehow survived upon them ... When my own Jim Chee of the Navaho Tribal Police unravels a mystery because he understands the ways of his people, when he reads the signs in the sandy bottom of a reservation arroyo, he is walking in the tracks Bony made 50 years ago."[11]

His Bony books were translated into German for the Goldmanns Taschenkrimi Series in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They were widely read and quite successful.[citation needed]

Books

[edit]| Title of book | Setting | Publication[12] |

|---|---|---|

| The House of Cain | Melbourne and NE of South Australia | Serialised: Perth Sunday Times (1928)

Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1928]; 1st US Edition: Dorrance, Philadelphia, 1929; 2nd US Edition: (pirated) Dennis McMillan, San Francisco, 1983. |

| The Barrakee Mystery | Near Wilcannia, New South Wales

First book to feature Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte |

Serialised: Melbourne Herald (1932)

Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1929]; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1965; 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1965 – as The Lure of the Bush. |

| The Beach of Atonement | Dongara, Western Australia[13] | Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1930]. |

| The Sands of Windee | 'Windee' is a fictional sheep station near Milparinka, a 150 miles (240 km) north of Broken Hill. Windee covered 1,300,000 acres (5,300 km2) of land and ran 70 000 sheep. | Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1931];

1st Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1958; 2nd UK Edition: Angus & Robertson, London, 1959. |

| A Royal Abduction | Cook and Eucla, on the Nullarbor Plain | Serialised: Melbourne Herald (1932) Hutchinson, London, [1932];

1st US Edition: (pirated) Dennis McMillan, Miami Beach, 1984. |

| Gripped by Drought | The fictional Atlas Station near Pooncarie, NSW | Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1932] |

| The Murchison Murders | Upfield's own account of the murders in the Murchison region | Midget Masterpiece Publishing, Sydney, n.d. [1934];

1st US Edition: (pirated) Dennis McMillan, Miami Beach, 1987. |

| Wings Above the Diamantina | In the region of the Diamantina River, which flows from Western Queensland into northern South Australia | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1936; 2nd Australian edition Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1940

1st UK Edition: Hamilton, London, n.d. [1937] – as Winged Mystery 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1943 – as Wings Above the Claypan. Serialised in Australian newspapers as When Wings are Clipped (1935). |

| Mr. Jelly's Business | Takes place at Burracoppin and Merredin east of Perth in the Wheat Belt of Western Australia along the rabbit-proof fence. The railway station in the story map and the water pipe have changed little since Upfield's day (he worked clearing brush in Burracoppin). | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1937; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1964

1st UK Edition: Hamilton, London, 1938 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1943 – as Murder Down Under. |

| Winds of Evil | Silverton, New South Wales, and the nearby Barrier Range, which is north and east of Broken Hill | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1937; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961

1st UK Edition Hutchinson, London, n.d. [1939] 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1944 |

| The Bone is Pointed | "Opal Town" or Opalton, Queensland, in the Channel Country of the Diamantina River | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1938; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1966

1st UK Edition: Hamilton, London, 1939 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1947; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, New York, 1946. Serialised in Australian newspapers as Murder on the Station (1938). |

| The Mystery of Swordfish Reef | Takes place from Bermagui, New South Wales; the reef extends from Montague Island. The plot is based on the 1880 disappearance of the geologist Lamont Young near Mystery Bay, New South Wales.[14] | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1939; Aust. Book Club Edition:Readers Book Club, Melbourne, 1963

1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1960; UK Book Club Edition: The Companion Book Club, London, 1963; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1971 1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1943 |

| Bushranger of the Skies | "McPherson's Station", 80 miles northwest of Shaw's Lagoon, South Australia. | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1940; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1963

1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Book Club, New York, 1944 – as No Footprints in the Bush |

| Death of a Swagman | Walls of China now in Mungo National Park, north-east of Buronga, far south-western NSW | 1st Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1947; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1962

1st UK Edition: Aldor, London, 1946 Doubleday/Crime Book Club, New York, 1945; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, New York, 1946 |

| The Devil's Steps | Set in a fictional mountain resort called Mount Chalmers, similar to the Dandenong Ranges on the eastern edge of Melbourne, Victoria (most probably in the vicinity of Mt Dandenong, but with some similarities to One Tree Hill in Ferny Creek), and also in Melbourne City and its suburbs South Yarra and Coburg. | 1st Australian Edition: Invincible Press, Sydney, n.d. [1950–1953]; 2nd Australian Edition: Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1965

1st UK Edition: Aldor, London, 1948 Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1946; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, New York, 1946 |

| An Author Bites the Dust | Set in the fictional town of Yarrabo, in the valley of the real Yarra River. | Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1948

1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1948; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, New York, 1948 |

| The Mountains Have a Secret | Set mostly in the Grampians mountain range in western Victoria. | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1952; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1948; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, New York, 1948 |

| The Widows of Broome | Set in Broome, Western Australia | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1951; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1967

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1950; US Book Club Edition: Dollar Mystery Guild, New York, 1950 |

| The Bachelors of Broken Hill | Broken Hill, New South Wales | 1st Australian Edition: Invincible Press, Sydney, between 1950 and 1953

1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1958; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified); Large Print Edition: Ulverscroft, Leicester, 1974 Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1950; US Book Club Edition: Detective Book Club, New York, 1951 |

| The New Shoe | Aireys Inlet; specifically, Split Point Lighthouse and Broken Rock[15] | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1952; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1968

Doubleday/Crime Book Club, New York, 1951 |

| Venom House | Set in and around "Edison", the real-life Elston, on the swampy coast south of Brisbane.(The name was later changed as Surfers Paradise) long before it became a tourist resort. | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1953; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1970

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1952; US Book Club Edition: Unicorn Mystery Club, New York, 1952 |

| Murder Must Wait | "Mitford", New South Wales, which is approximately where real-life Wentworth is located. Various references indicate far west of New South Wales. | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1953; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1953; US Book Club Edition: Detective Book Club, New York, 1953 |

| Death of a Lake | East of Menindee. Said to be Victoria Lake (not Lake Victoria), an ephemeral lake that fills occasionally in massive River Darling floods. | Heinemann, London, 1954

1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1954 |

| Cake in the Hat Box; also published as Sinister Stones | Kimberley region of Western Australia "Agar's Lagoon" is Hall's Creek. | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1955 ; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1954 as Sinister Stones |

| The Battling Prophet | The Cowdry River, a fictional river south of Mount Gambier. | Heinemann, London, 1956; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified) |

| The Man of Two Tribes | Nullarbor Plain | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1956 – as Man of Two Tribes; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1956 |

| Bony Buys a Woman; also published as The Bushman Who Came Back | Lake Eyre region | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1957

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1957 - as The Bushman Who Came Back |

| Follow My Dust! | Heinemann, London, 1957 | |

| Bony and the Black Virgin; also published as The Torn Branch | "Lake Jane", a fictional lake in the Murray–Darling Basin[16] | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1959; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified) |

| Bony and the Mouse; also published as Journey to the Hangman | "Daybreak", a fictional mining town 150 miles (240 km) from Laverton, Western Australia | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1959 – as Bony and the Mouse; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York. 1959 as Journey to the Hangman |

| Bony and the Kelly Gang; also published as Valley of Smugglers | Possibly set in a town and valley similar to Kangaroo Valley, New South Wales, not far from Bowral where Upfield lived for the last years of his life.[17] However, Robertson on the top of the escarpment, which is known for its potatoes, is also possible.

The waterfall may be Fitzroy Falls in Morton National Park.[16] Narrates some episodes of the Ned Kelly true history. |

1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1960; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1960; US Book Club Edition: Detective Book Club, New York, n.d. [1960] – as Valley of the Smugglers |

| The White Savage | Timbertown is a light disguise of Pemberton, a timber town in the south-west of Western Australia. | 1st UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1961 – as Bony and the White Savage; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified)

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1961 |

| The Will of the Tribe | Wolfe Creek Crater[16] | First UK Edition: Heinemann, London, 1962

Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1962 |

| Madman's Bend | Hard to tell along which stretch of the Darling River this was. Upfield spent time around Menindee where some large, dense, river redgum forests fit the bill that are within Kinchega National Park. A section of river near here is called Lunatic Bend just south of the township. | Heinemann, London, 1963

1st US Edition: Doubleday/Crime Club, New York, 1963 – as The Body at Madman's Bend |

| The Lake Frome Monster

[Note: This posthumously published work was based on an unfinished manuscript and detailed notes left by Upfield. It was completed by J L Price and Mrs Dorothy Strange.] |

Lake Frome, South Australia | Heinemann, London, 1966; 2nd UK Edition: Heinemann, London, (date not identified) |

| Breakaway House | Serialised: Perth Daily News (1932)

Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1987 | |

| The Great Melbourne Cup Mystery | Serialised: Melbourne Herald (1933)[18]

ETT Imprint, Watson's Bay, Sydney, 1996 | |

| The Gifts of Frank Cobbold | The Cobbold Family History Trust, written in 1935 and expanded from a short story ‘The Mysterious Notes’, published anonymously in the Fitzroy City Press on 23 May 1914; the manuscript was edited and revised by Sandra Berry in 2008 |

Radio

[edit]Wings Above the Diamantina was adapted for radio in 1939 starring Ron Randell as Boney.[19]

The Bone is Pointed was serialised in 1948.[20]

There was a radio series in the 1950s Man of Two Tribes starring Frank Thring as Boney.

Novels would be read out in serial form on the radio, including:

Television series

[edit]From 1972 to 1973, Fauna Productions produced a 26-episode television series based on the books. Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte was played by New Zealand actor James Laurenson. The series was called Boney. Most of the episodes were based directly on one of the novels, but there were some adaptations. Two original scripts were not directly based on any novel; five novels were not adapted for television, effectively "reserving" them in case a third series was produced. At the time, many of the books were reprinted with the spelling altered to "Boney" on the covers (although retaining the original in the text), and featuring a photo from the relevant episode.[25]

Bony was also a 1990 telemovie and later a 1992 spin-off TV series (using the original "Bony" spelling). However, the series was criticised for casting Bony as a white man (played by Cameron Daddo), under the tutelage of "Uncle Albert", an elderly Aboriginal man played by Burnum Burnum.

Short stories

[edit]- His Last Holiday. Brisbane Daily Standard, 14 January 1916

- The Man Who Liked Work. Life, January 1928

- Laffer's Gold. Western Mail, 22 December 1932

- Rainbow Gold. Perth Sunday Times, 29 January 1933

- [Title Unknown]. Jarrah Leaves, 30 November 1933

- [Title Unknown]. Australian Journal, January 1934

- [Title Unknown]. Australian Journal, October 1935

- Henry's Last Job. Melbourne Herald, 14 February 1939

- A Mover of Mountains. Melbourne Herald, 14 October 1939

- Henry's Little Lamb. Melbourne Herald, 5 December 1939

- Joseph Henry's Christmas Party. Melbourne Herald, 23 December 1939

- Pinky Dick's Elixir. Melbourne Herald, 18 January 1940

- Vital Clue. Melbourne Herald, 19 January 1940

- Why Did the Devil Shoot a Pig?. Melbourne Herald, 29 January 1940

- That Cow Maggie!! Melbourne Herald, 11 April 1940

- The Great Rabbit Lure. Melbourne Herald, 19 April 1940

- The Colonel's Horse. ABC Weekly, 5 January 1941

- The Cairo Spy. ABC Weekly, 5 July 1941

- Through Flood and Desert for Twopence. ABC Weekly, 26 October 1941

- White Quartz. Adelaide Chronicle, 21 November 1946

- M-U-R-D-E-R at Split Point. Melbourne Argus, 27 December 1952 to 2 January 1953. (Heavily edited version of The New Shoe)

Non-fiction

[edit]- All Must Pay: Reflections on Outpost. Melbourne Argus, 8 January 1916

- Little Stories of Gallipoli. Melbourne Argus, 10, 14, 19 and 21 January 1916

- The Blight. Barrier Miner, 4, 11, 18 and 25 October 1924

- ’’At School Today and Forty Years Ago’’. West Australian, 10 March 1928

- ’’The Loneliest Job on Earth’’. Wide World Magazine, December 1928

- Reynard the Killer: A Growing Menace to Pastoralists: Bush Life Becoming Extinct. Perth Sunday Times, 31 August 1930

- Aboriginal Philosophy. West Australian, 20 September 1930

- Face and Clothes. West Australian, 22 November 1930

- ’’Eucla - An Abandoned Township and it’s Ghost’’. Empire Review, December 1930

- Sep-Ah-Rate. West Australian, 17 October 1931

- Some Reflections on a Hilltop: The Charm of the Ranges: A Nomad's Heart Responds. Perth Daily News, 9 July 1932

- Lords of the Track: Sundowners I Have Met: Nicknames and Fads. Perth Daily News, 30 July 1932

- After Rain: Charms of Hill and Gully: The Song of the Brook Perth Daily News, 6 August 1932

- Street Mysteries: Sidelights in the Study of Humanity. Perth Sunday Times, 18 September 1932

- The Hunted Emu: A Rural Pest Which Is a Pest Destroyer. Perth Sunday Times, 13 November 1932

- Kangaroo Coursing: The Thrill of a Blind Chase. West Australian, 19 November 1932

- Christmas Memories. Perth Daily News, 24 December 1932

- Plagues of Australia: Wonders of Animal Migration. West Australian, 31 December 1932

- Literary Illusions: Some Experiences of an Author - and Others. Perth Sunday Times, 1 January 1933

- Way for the Pioneers! Migration Needs a New Deal. Melbourne Herald, 3 January 1933

- Australia. West Australian, 14 January 1933

- Let Us Go Beachcombing: The Perfect Dream for Hot Weather Days. Perth Daily News, 9 February 1933

- The Man Who Thought He Was Dead. Melbourne Herald, 28 October 1933

- Future of the Aborigines: New Protective Laws Required. Perth Daily News, 2 November 1933

- Found - An Old Tyre! A Problem of the Bush. Melbourne Herald, 11 November 1933

- Lonely Terrors of the Bush! The Man Who Lost Count! Melbourne Herald, 25 November 1933

- Untitled article. Brisbane Sunday Mail, 26 November 1933

- Justice for the Black. Try New Treatment! Melbourne Herald, 1 December 1933

- Land of Illusions: Do We Expect Too Much from the Northern Territory: Dangers of Boosting. Melbourne Herald, 19 December 1933

- My Life Outback: Surveyor, Cook and Raw Boundary Rider: The Breaking-in Begins. Melbourne Herald, 12 January 1934

- Poison! Tales of the Nonchalant Bush. Melbourne Herald, 13 January 1934

- Outback Adventures of a 'New Chum': A Dream and the Sad Awakening. Adelaide Advertiser, 13 January 1934

- My Life Outback, No. 2: Mule Driver's Outsider: On the Track with One-Spur Dick. Melbourne Herald, 13 January 1934

- My Life Outback No. 3: Opal Gouging with Big Jack - and His Cat: How Joke on New Chums Became Good Turn. Melbourne Herald, 15 January 1934

- My Life Outback, No. 7: When Crabby Tom Ran Amok. Melbourne Herald, 19 January 1934

- Up and Down Australia, No. 1: Going Bush. West Australian, 26 January 1934

- Kangaroo Coursing. Melbourne Herald, 27 January 1934

- My Life Outback, No. 8: Sand-storm Terror in Sturts County, No. 8. Melbourne Herald, 29 January 1934

- My Life Outback, No. 11: The Murchison Bones Murder Case. Melbourne Herald, 24 January 1934

- Up and Down Ausrealia, No. 2: Mule Driver's Offsider. West Australian, 2 February 1934

- My Life Outback, No. 5: Tramping by the Darling. Adelaide Advertiser, 10 February 1934

- My Old Pal Buller: Two Camels and - a Scorpion. Melbourne Herald, 10 March 1934

- Plot for a Murder Mystery: Planning a Perfect Crime. Adelaide Advertiser, 17 March 1934

- The Real Australia: The Sheep They Couldn't Kill. Melbourne Herald, 17 March 1934

- The Real Australia: How They Waited for the Rain: The Courage of One Woman. Melbourne Herald, 31 March 1934

- Challenging America! How the Yacht Endeavour was Built. Melbourne Herald, 9 June 1934

- Work of the Bird gatherer. Adelaide Chronicle, 11 July 1934

- Fun For The Afternoon! The Tale of an Intelligent Bull in the Outback. Melbourne Herald, 28 July 1934

- A Tale of Two Worlds. Melbourne Herald, 9 August 1934

- Ringers of the Bells: Secrets of an Ancient Art. Melbourne Herald, 17 November 1934

- Black Man's Eldorado: Rich Reefs of the Imagination. Adelaide Chronicle, 16 May 1935

- The Real Australia. Adelaide Chronicle, 13 June 1935

- Walls of China. Melbourne Herald, 6 November 1937

- His Majesty - The Swordfish. Melbourne Herald, 24 March 1938

- The Art of Writing Mystery Stories. Adelaide Advertiser, 20 July 1940

- The Impossible Perfect Crime. Adelaide Chronicle, 8 December 1949

References

[edit]- ^ "Arthur Upfield". Bookorphanage.com. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d Liukkonen, Petri. "Arthur Upfield". Books and Writers. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018.

- ^ a b "The Arthur Upfield Mystery – Bony (transcript of radio show 12 May 2002)". Radio National, Books and Writing. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2002. Archived from the original on 22 April 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2006.

- ^ Walker, Terry (1993). Murder on the Rabbit Proof Fence: The strange case of Arthur Upfield and Snowy Rowles. Carlisle, Western Australia: Hesperian Press. ISBN 0-85905-189-7.

- ^ "First World War Unit Embarkation Rolls (search for Arthur Upfield)". Nominal rolls. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 3 February 2006.

- ^ Upfield, Arthur (19 April 1934). "One Digger's War". Melbourne Herald. Copy of article with Upfield's World War 1 Military Records held by the National Archives of Australia.

- ^ a b Jonathan Vos Post (2004). "Arthur Upfield". Periodic Table of Mystery Authors. Magic Dragon Multimedia. Retrieved 15 January 2006.

- ^ Caroline Baum, "The Case of the Disappearing Detective", The Age, Good Weekend magazine, 20 January 2007, p. 26

- ^ a b c Peter Pierce, ed. (1987). The Oxford Literary Guide to Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 30, 33, 302.

- ^ Kees de Hoog (2004). "Arthur W. Upfield, Creator of Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte (Bony) of the Queensland Police". Collecting Books and Magazines. www.collectingbooksandmagazines.com/. Retrieved 9 February 2006.

- ^ deHoog, Kees; Hetherington, Carol, eds. (2011). "Upfield: The Man Who Started It". Investigating Arthur Upfield: A Centenary Collection of Critical Essays. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1443834957.

- ^ Barry John Watts. "Arthur Upfield and Detective-Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte of the Queensland Police". Pegasus Book Orphanage. Archived from the original on 26 February 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2006.

- ^ "'Beach of Atonement' Discussion Forum". Famous Folk Arthur W. Upfield Discussion Forum. www.proboards.com. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- ^ "Bermagui". Travel. Fairfax Digital. 2004. Archived from the original on 27 April 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2006.

- ^ N.L. Nicholson (2003). "Images of the Lighthouse and Eagle Rock featuring in Upfield's Novel, "The New Shoe"". Dingo's Breakfast Club: Australian Natural History; Human ecological context for the "Bony" mysteries by Arthur William Upfield. nicholnl.wcp.muohio.edu. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- ^ a b c N.L. Nicholson (2003). "Australian Natural History; Human ecological context for the "Bony" mysteries by Arthur William Upfield". Dingo's Breakfast Club. nicholnl.wcp.muohio.edu. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- ^ "The Wild, Wombat's Wonderings!Part 4 [sic]". (Journal of trip to Australia in 1999–2000). The Latham-Albany-Schenectady-Troy Science Fiction Association. 2000. Archived from the original on 15 January 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2006.

- ^ "The Great Melbourne Cup Mystery". The Herald. No. 17, 609. Victoria, Australia. 21 October 1933. p. 24. Retrieved 27 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Australasian Radio Relay League. (13 September 1939), "Upfield Mystery Pleases", The Wireless Weekly: The Hundred per Cent Australian Radio Journal, 34 (25), nla.obj-726296197, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission. (24 July 1948), "THRILLING NEW MORNING SERIAL", ABC Weekly, 10 (30), nla.obj-1431112856, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission. (19 October 1940), "FRIDAY DETAILS OF HIGHLIGHTS IN TO-DAY'S A B C PROGRAMMES", ABC Weekly, 2 (42), nla.obj-1309225727, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission. (12 November 1955), "2FC-2NA THURSDAY", ABC Weekly, 17 (45), nla.obj-1542309238, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission. (7 July 1956), "2FC-2NA WEDNESDAY", ABC Weekly, 18 (27), nla.obj-1317572111, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission. (1 April 1959), "the RADIO Programmes 2FC-2NA (FROM 5.59 a.m. TO 12.30 p.m.)", ABC Weekly, 21 (13), nla.obj-1538075875, retrieved 13 January 2024 – via Trove

- ^ "Boney". Classicaustraliantv.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

Further reading

[edit]- de Hoog, Kees & Hetherington, Carol (editors) (2012). Investigating Arthur Upfield: A Centenary Collection of Critical Essays. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-3452-0. These critical essays mark the centenary of Upfield's arrival in Australia from England on 4 November 1911.

External links

[edit]- "Arthur Upfield Official Site". A guide to the Bony detective novels. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Boney, television series 1972–1973 at IMDb

- Works by Arthur W. Upfield at Faded Page (Canada)

- Robert Wilfred Franson (2004). "Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte series by Arthur W. Upfield". Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2006.

- Don Storey (2005). "Boney". Classic Australian Television. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2006.

- Kay Craddock (Antiquarian bookseller). "Catalogue (of Upfield's works with publication details of various editions)" (PDF). University of Melbourne Library: Special collections section. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2006.

- Works by Arthur Upfield at Open Library

- Arthur W. Upfield, Creator of Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte (Bony) of the Queensland Police

- Travis B. Lindsey, Arthur William Upfield: A Biography. Thesis for Ph.D. degree, Monash University, 2005.

Arthur Upfield

View on GrokipediaArthur William Upfield (1 September 1890 – 12 February 1964) was an English-born Australian writer best known for his detective fiction novels set in the remote Australian bush, featuring the mixed-race Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte as the protagonist.[1] After arriving in Australia in late 1911, Upfield enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force shortly after the outbreak of World War I, serving as a driver during the Gallipoli campaign and marrying nurse Anne Douglass in Egypt in 1915; he was discharged in 1919 and returned to bush work that shaped his intimate knowledge of outback life and Aboriginal customs.[1] His writing career produced 29 Bonaparte novels, beginning with The Barrakee Mystery in 1929, which incorporated realistic depictions of Australian landscapes and indigenous tracking skills, earning him prominence as the first non-American full member of the Mystery Writers of America.[1] A notable aspect of his legacy involves the real-world echo of his unpublished plot in The Sands of Windee (1931), where a method of body disposal was emulated by murderer Snowy Rowles in the Murchison killings, inadvertently boosting Upfield's fame through the ensuing trial.[1][2] Upfield's works emphasized empirical bushcraft and causal problem-solving over urban tropes, reflecting his twelve years of hands-on experience as a jackaroo and tracker.[2]

Biography

Early Life in England

Arthur William Upfield was born on 1 September 1890 at 87-88 North Street in Gosport, Hampshire, England, the eldest of five sons to James Oliver Upfield, a prosperous draper, and Annie Upfield (née Barmore), a former shop assistant.[1][3][4] He was christened William Arthur Upfield on 9 October 1890 at Gosport Methodist Church.[4] His family's middle-class circumstances provided a stable environment, though Upfield was primarily reared by his grandparents following his mother's early death.[1] Upfield received his education at Blenheim House, a private school in nearby Fareham.[1] He left school around age 16 and was initially apprenticed to Puttock & Blake, a firm of surveyors in Gosport.[1] At 19, he was articled to an estate agency, aspiring to a career in real estate, but failed the qualifying examinations after devoting excessive time to reading adventure novels rather than studying.[1][3] These early setbacks in professional training reflected Upfield's growing disinterest in sedentary clerical work and foreshadowed his later affinity for outdoor pursuits, though his time in England remained confined to the coastal town of Gosport and its environs.[2] By 1911, at his father's urging, he emigrated to Australia seeking broader opportunities.[1][2]Migration and Settlement in Australia

Upfield, born in Gosport, Hampshire, England, emigrated to Australia in 1911 at the direction of his father, a draper who sought to instill discipline after Upfield showed little aptitude for training as a real estate surveyor.[5] [1] He departed England following unsuccessful examinations and arrived in Adelaide, South Australia, on 14 November 1911, aged 21.[6] [7] Upon arrival, Upfield eschewed urban prospects for the outback, roaming through New South Wales and Queensland while taking up itinerant bush labor such as droving, station hand duties, opal mining, and boundary riding.[1] This nomadic phase reflected his affinity for rugged frontier life, with no fixed residence established before his enlistment in the Australian Imperial Force on 23 August 1914 as a driver with the 1st Light Horse Regiment.[2] Following World War I service, Upfield returned to Australia in 1920 with his English wife, Jessie, and infant son, initially basing near Melbourne where he briefly worked on a dairy farm and in a factory before resuming bush travels.[4] [8] He undertook extended roles, including five years patrolling Western Australia's No. 1 rabbit-proof fence from 1924, which provided material for his later writing.[6] Permanent settlement came later; by the 1940s, Upfield resided in Bowral, New South Wales, at 3 Jasmine Street, a southern highlands town that served as his base for writing until his death in 1964.[7] This progression from transient laborer to established resident underscored his integration into Australian society, culminating in naturalization as an Australian citizen.[1]Military Service in World War I

Upfield enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 22 August 1914, shortly after the declaration of war.[1] Assigned service number 143 and the rank of driver, he was allotted to the 1st Light Horse Brigade Train, specifically 5 Company of the Australian Army Service Corps, a unit responsible for logistical support including transport of supplies.[9] He embarked from Brisbane in September 1914 aboard the HMAT Anglo-Egyptian (A25), bound for the Middle East.[9] In the Middle East, Upfield's unit participated in the Gallipoli campaign, where he served in a driver capacity amid the Allied efforts to capture the Ottoman peninsula beginning in April 1915.[1] Although not among the initial Anzac landing forces on 25 April, his role involved supporting the mounted troops dismounted for trench warfare on the rugged terrain.[3] Following the evacuation of Gallipoli in December 1915, he continued service in Egypt, where he married Australian nurse Anne Douglass in 1915.[2] During this period, he occasionally acted as sergeant.[1] Upfield transferred to the Western Front in August 1916, serving as a driver with the 1st Division Train of the Australian Army Service Corps in France, handling supply convoys amid ongoing trench warfare.[1] He was invalided from front-line duties in January 1917 due to health issues, though details of the condition are not specified in records.[1] After recovery, he remained in service, eventually being discharged in London on 15 October 1919.[1][10]Personal Relationships and Family

Upfield was the eldest of five sons born to James Oliver Upfield, a draper, and his wife Annie (née Barmore) in Gosport, Hampshire, England.[1] Due to limited space in the family home, which doubled as a draper's shop, he was primarily raised by his paternal grandmother and two great-aunts.[4] On 3 November 1915, while recovering from gastritis in a hospital near Alexandria, Egypt, Upfield married Australian Army nurse Anne Douglass at the British Consulate General there; she was subsequently dismissed from nursing service for the marriage.[1] [11] The couple had one son, James Arthur Upfield, born on 8 February 1920 near Stockbridge, Hampshire.[11] After Upfield's discharge from military service in England on 15 October 1919, they returned to Australia in 1921, but the marriage deteriorated amid his nomadic bush work and financial strains, leading to separation shortly thereafter.[1] [11] Formal asset division occurred in 1946, including equal shares of property and maintenance, though Anne never agreed to divorce; she died on 29 June 1964 in Geelong, Victoria.[11] In August 1945, Upfield entered a de facto partnership with widow Jessica Hawke (born 1907, later known as Uren and then Upfield by deed poll on 15 June 1955), with whom he cohabited from May 1946 at Yarra Junction, Victoria, until his death.[11] [1] Described as harmonious and quarrel-free, this 17-year relationship involved Jessica managing his literary and personal affairs, including extensive correspondence during his travels and co-authorship of his 1957 autobiography Follow My Dust!.[11] They had no children together, but Upfield mentored Jessica's son Donald Uren from her prior marriage, encouraging his rural career pursuits.[11] Upfield maintained limited contact with his son James, who married twice—first to Betty Jeanetta Lambarn in 1944 (annulled shortly after) and later to Dorothy, with whom he had a son, William Arthur Upfield, born in June 1948.[11] Upfield died on 12 February 1964 in Bowral, New South Wales, survived by James.[1]Pre-Writing Career

Bush Work and Outback Experiences

Upon arriving in Adelaide on 4 November 1911 aboard the RMS Orvieto, Upfield initially took manual labor roles, including work on a wheat farm at Pinnaroo in South Australia, where he handled tasks such as feeding and harnessing horses and stripping crops, followed by employment as a fourth cook in a large Adelaide hotel.[11] These early positions marked his transition from urban settings to rural bush life, fostering an affinity for the Australian landscape.[11] From 1911 to 1914, Upfield engaged in outback work across New South Wales, the Northern Territory, and Queensland, including soldering, teamstering, and tracking at Momba Station near Wilcannia in New South Wales; serving as a boundary rider patrolling an 80-mile vermin-proof fence using camels; droving cattle from Daly Waters in the Northern Territory to Longreach in Queensland; and laboring at Toombul Vineyards near Nudgee in Queensland.[11] After his World War I service and return to Australia in 1920, he resumed bush employment in 1921, leaving a factory job in Melbourne to take up roles such as stockmen's cook and camel-driving fence-patroller in regions including New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia.[1] [11] In the late 1920s, Upfield's outback pursuits intensified, with activities such as clearing karri and jarrah forest growth in southwest Western Australia in 1927; patrolling the 163-mile No. 1 Rabbit-Proof Fence from Burracoppin to Dromedary in Western Australia from 1927 to 1929 using a camel-drawn dray; trapping over 800 fox pelts in ten weeks near Lake Victoria in New South Wales as a full-time trapper; boundary riding along the South Australia-New South Wales border; cooking for station hands in Queensland; and driving a truck across the Nullarbor Plain.[11] By 1929–1932, he continued fence patrolling on the No. 1 Rabbit-Proof Fence, covering approximately 100 miles north and south of Burracoppin, alongside supplementary tasks like rabbit trapping and controlled burning.[11] Upfield's diverse manual roles extended to droving cattle, acting as a mule driver's offsider, surveying, fur trapping, and station hand duties, often in remote areas like the Murchison region of Western Australia and along the Darling River in New South Wales.[11] These experiences, spanning roughly twelve to twenty years in the outback until around 1931, provided him with practical knowledge of bush survival, tracking, and interactions with Aboriginal trackers and communities, which he later drew upon for authenticity in his narratives.[2] [1]Professional Roles and Influences

Upon arriving in Adelaide, South Australia, in 1911, Upfield initially worked as a kitchen hand, gardener in the suburb of Mitcham, and briefly at the South Australia Hotel before transitioning to rural labor.[4] He soon ventured into the outback as a jackeroo and boundary rider at Momba Station near Wilcannia, New South Wales, gaining early exposure to station life and bush survival.[4] Between 1920 and 1922, he took up dairy farm and factory work near Melbourne, but these urban-adjacent roles proved unsatisfying compared to the frontier.[4] Following his discharge from military service in 1919 and a brief stint as a private secretary to an army officer in England until 1921, Upfield returned to Australia and immersed himself in diverse outback occupations for approximately twelve years, primarily from 1921 to 1936.[2] These included boundary rider, cattle drover, rabbit trapper, station manager, stockmen's cook, camel-driving fence patroller, sheep herder, opal gouger, grape picker, and general station hand across New South Wales, Queensland, and Western Australia.[1] Such roles demanded practical mastery of arid landscapes, animal husbandry, and rudimentary tracking, fostering self-reliance amid isolation.[1] Upfield's prolonged bush tenure profoundly shaped his later detective fiction by imparting firsthand insight into Aboriginal lore, environmental hazards, and tracking techniques integral to his protagonist, Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte.[2] The character's hybrid expertise—blending Western deduction with Indigenous methods—drew directly from Upfield's observations of Aboriginal survival skills and encounters with mixed-descent trackers like Leon Wood, whom he met in Queensland.[2] Real events, such as the 1931-1932 Murchison murders trial in Western Australia, further influenced plots like that of The Sands of Windee (1931), where outback isolation and forensic improvisation mirrored his lived realities.[2] This experiential foundation lent authenticity to his portrayals of the Australian interior's unforgiving dynamics, distinguishing his work from urban-centric mysteries.[1]Literary Career

Entry into Writing

Upfield's formal entry into writing occurred after his return to Australia from military service in 1921, when he was encouraged by the wife of a station owner on a property along the Darling River in New South Wales to compose stories based on his outback experiences.[1] Drawing from his itinerant bush work, he initially produced articles, short stories, and nature pieces for newspapers and magazines, leveraging his firsthand knowledge of remote Australian landscapes and Aboriginal customs.[5] By the late 1920s, Upfield intensified his efforts while working as a cook at the isolated Wheeler's Well in New South Wales, dedicating spare time to crafting full-length novels in the crime fiction genre.[3] His debut publication, The House of Cain, a thriller about a murderer hosting fellow criminals, was released by Hutchinson in London in 1928.[12] [13] In 1929, Upfield followed with The Barrakee Mystery, published by Hutchinson, which introduced his enduring detective protagonist, Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte—a half-Aboriginal tracker inspired by real-life figure Leon Wood.[1] [3] This novel, serialized earlier in the Melbourne Herald, established Upfield's focus on outback mysteries blending empirical tracking methods with narrative realism, though initial royalties proved insufficient for sustenance.[1] By 1931, he left bush employment to take a feature-writing position at the Melbourne Herald, allowing greater dedication to literature amid ongoing financial precarity.[1]Development of the Napoleon Bonaparte Series

Upfield created the character of Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, a half-Aboriginal police officer known as Bony, drawing inspiration from Leon Wood, a part-Aboriginal tracker employed by the Queensland Police whom he observed during his outback travels spanning 1921 to 1933.[2] Bony's exceptional tracking abilities and cultural duality reflected Upfield's firsthand encounters with Aboriginal survival techniques in harsh environments, including his roles as a boundary rider and rabbit-proof fence patrolman from 1927 to 1931.[11] These experiences informed Bony's methodology, blending scientific deduction with Indigenous knowledge, as Upfield sought to portray a figure bridging racial divides amid 1920s Australian policies restricting Aboriginal rights.[11] Bony first appeared in The Barrakee Mystery, published in February 1929 by Hutchinson in London, where the detective investigates an Aboriginal death on a remote New South Wales station.[11] Upfield revised the manuscript following agent feedback on pacing and structure, marking an early challenge in refining the series' blend of outback realism and procedural elements.[11] The second novel, The Sands of Windee (1931, Angus & Robertson in Australia and Hutchinson in the UK), expanded Bony's role in solving a disappearance amid opal fields, incorporating a murder method—dissolving a body in acid—that Snowy Rowles later replicated in the 1932 Murchison murders, drawing public attention to Upfield's work.[2][11] The series evolved over 29 novels through 1966, with Upfield integrating real locations like Broome and the Wolf Creek crater and anthropological details from sources such as Baldwin Spencer and F.J. Gillen's Across Australia (1912) for authenticity in tracking scenes.[11] Publication shifted to U.S. success via Doubleday from 1943, retitling early works like Mr. Jelly's Business (1937) as Murder Down Under, while Australian recognition lagged due to publisher preferences for British markets and critiques of Bony's mixed heritage as morally ambiguous.[11] Upfield occasionally downplayed Bony's Aboriginal traits in titles like An Author Bites the Dust (1948) to appeal to international audiences but restored them in later entries, incorporating social commentary on Indigenous marginalization amid evolving postwar attitudes.[11] Challenges included rejections, such as Cake in the Hatbox reworked as Sinister Stones (1954), and disputes with publishers like Angus & Robertson, yet the series maintained consistent remote Australian settings and Bony's unflappable persona.[11] The final novel, The Lake Frome Monster (1966), was completed posthumously by collaborators J.L. Price and Dorothy Strange.[11]Later Productivity and Challenges

In the years following World War II, Upfield resumed full-time writing after a hiatus, producing a steady stream of Napoleon Bonaparte detective novels amid growing international demand, particularly in North America where his works gained popularity through outlets like the Crime Club.[4] Key publications from this period included An Author Bites the Dust in 1948, The New Shoe in 1951, Death of a Lake in 1954, Bony and the White Savage in 1961, and the posthumously completed The Lake Frome Monster in 1966.[1] By the time of his death, he had authored 29 novels featuring the detective, alongside other fiction, sustaining a career that spanned from 1928 to 1964 with Australian outback settings drawn from his earlier experiences.[1] Upfield's later productivity was hampered by persistent health challenges, stemming from a severe nervous and orthopaedic illness coupled with an apparent heart attack in 1936, from which he never fully recovered his physical strength.[4] A major heart attack in 1951 exacerbated his condition, leading to ongoing illnesses that curtailed his ability to conduct fieldwork in the outback—travels he had previously undertaken annually to inform his authentic depictions of remote Australian landscapes.[4][14] By 1962, a marked decline in health confined him largely to his home at 3 Jasmine Street in Bowral, New South Wales, though he rallied sufficiently to begin another Bony novel, conduct interviews, and occasionally visit Sydney.[15] These physical limitations did not entirely derail his output, as Upfield adapted by relying on accumulated knowledge and memory, but they contributed to a shift toward more sedentary writing in his final years.[15] Personal circumstances added further strain; after separating from his wife in 1946 without divorce, he lived with Jessica Hawke, who supported his work and later co-authored biographical material from his unpublished memoirs, such as Follow My Dust in 1957.[2] Upfield died on 12 February 1964 at Bowral, aged 73, from complications related to his long-term health issues.[1]Literary Works

Detective Novels Featuring Napoleon Bonaparte

Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, known familiarly as Bony, is a fictional Queensland police officer of mixed European and Aboriginal descent, orphaned young and raised within white Australian society while retaining profound expertise in traditional Aboriginal tracking methods.[3] University-educated and methodical, Bonaparte combines empirical observation of subtle environmental clues—such as bent grass or displaced pebbles—with forensic science and psychological insight to resolve crimes in Australia's vast, sparsely populated regions, often outback cattle stations, mining towns, or desert expanses where conventional policing proves inadequate.[3][16] Upfield drew inspiration for the character from real Aboriginal trackers encountered during his bush travels, including one named Tracker Leon, who gifted him a book on Napoleon Bonaparte that influenced the detective's nomenclature.[3] The Bonaparte series, comprising 29 novels published from 1929 to 1963, constitutes Upfield's most enduring contribution to detective fiction, emphasizing realism derived from his firsthand outback experiences rather than contrived puzzles.[17] These works typically unfold in isolated Australian locales, highlighting causal chains of events rooted in environmental determinism, human error, and rudimentary motives like greed or revenge, with Bonaparte's biracial perspective enabling detections overlooked by urban-trained colleagues.[18] One notable entry, Murder Down Under (1945), incorporates empirical details from the real-life 1929 Snowy Rowles poisoning case in Western Australia, where strychnine-laced saddlery concealed murders, mirroring Upfield's own observations as a trial witness.[19] The novels in publication order are as follows:| Title | Original Publication Year |

|---|---|

| The Barrakee Mystery (also The Lure of the Bush) | 1929 |

| The Sands of Windee | 1931 |

| Wings Above the Diamantina | 1936 |

| The Bone is Pointed | 1938 |

| The Mystery of Swordfish Reef | 1943 |

| Murder Down Under | 1945 |

| The Devil's Steps | 1946 |

| An Author Bites the Dust | 1948 |

| Death of a Swagman | 1945 (Australian edition; U.S. 1950) |

| The Bachelors of Broken Hill | 1950 |

| The New Shoe | 1951 |

| Venom House | 1952 |

| Sinister Stones | 1954 |

| The Battling Prophet | 1956 |

| Deadly Is the Diamond | 1957 |

| The Lakes of the Devil's March | 1958 |

| False Queen | 1959 |

| The Fall of Colonel Falthorpe | 1960 |

| The Body at Madman's Bend | 1963 (posthumous U.S. edition; Australian 1967 as Madman's Bend) |

| Cake in the Hat Box | 1960 |

| The White Swan Murder | 1968 (posthumous) |

| Bony and the Black Virgin | 1959 |

| Bony and the Kelly Gang | 1960 |

| Bony and the Mouse | 1961 |

| Journey to the Hangman | 1961 |

| The Dividing Stream | 1961 |

| A Royal Bloodstain | 1962 |

| The Will of the Tribe | 1962 |

| The Lake Frome Monster | 1966 (posthumous) |