Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

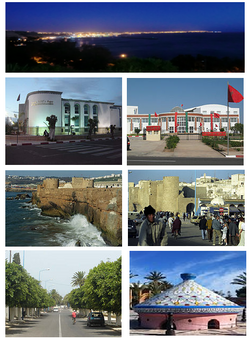

Safi, Morocco

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) |

Safi (Arabic: آسفي, romanized: ʾāsafī) is a city in western Morocco on the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of Asfi Province. It recorded a population of 308,508 in the 2014 Moroccan census.[1] The city was occupied by the Portuguese Empire from 1488 to 1541, was the center of Morocco's weaving industry, and became a fortaleza of the Portuguese Crown in 1508.[2] Safi is the main fishing port for the country's sardine industry, and also exports phosphates, textiles and ceramics. During the Second World War, Safi was the site of Operation Blackstone, one of the landing sites for Operation Torch.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]11th-century geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi gave an explanation to the origin the name "Asafi" as he linked it to the Arabic word "Asaf" (regret); Asafi (my regret). He based this claim on a strange story about some sailors from al-Andalus who sailed to discover the other end of the Atlantic Ocean but got lost and landed on some island where the natives captured them and sent them back on their ships blindfolded. The ships eventually ended on the shores of "Safi" and locals helped the lost sailors and told them that they were two months away from their native land al-Andalus. Upon hearing this one of the sailors responded by saying: "Wa asafi" (Oh my regret). Al-Idrisi wrote that from that time the city carried the name "Asafi".[3]

History

[edit]According to historians Henri Basset and Robert Ricard, Safi was not a very ancient city.[4] It was mentioned in the writings of al-Bakri in the 11th century and of al-Idrisi in the 12th century.[4] According to Moroccan historian Mohammed al-Kanuni, Safi can be identified with the ancient Thymiaterium or Carcunticus that was founded by the Carthaginian admiral Hanno during his Periplus, as related by Pliny the Elder.[5]

Al-Idrisi mentions Safi as a busy port in the 12th century.[4] At this time it served as a port for Marrakesh, the capital of the Almoravids and the subsequent Almohads, replacing the port of Ribat Kuz (present-day Souira Kedima) that had served as the main port for Aghmat in the previous century.[6]

The city was under Portuguese rule from 1488 to 1541; it is believed that they abandoned it to the Saadians (who were at war with them), since the city proved difficult to defend from land attacks. The Sea Castle and Kechla, two Portuguese fortresses built to protect the city, are still there today.

After 1541, the city played a major role in Morocco as one of the safest and biggest seaports in the country. Many ambassadors to the Saadian and Alaouite kings during the 16th–18th centuries came to Morocco via Safi; its proximity to Marrakech, then capital of Morocco, helped expand the maritime trade in the city.

Louis De Chénier, consul of the French court in Morocco in 1767, reported that the city was the only usable seaport at the time.

A French Navy captive, Bidé de Maurville, who wrote the account of his stay in Morocco in his 1765 book Relations de l'affaire de Larache, reported the presence of an important number of foreign trading houses in the city: Dutch, Danish, British and French.

After the Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah built the city of Mogador (modern-day Essaouira), he banned foreign trade in all Moroccan ports except in his newly built city. Consequently, Safi stopped playing a leading role in the Moroccan trade.

Safi's patron saint is Abu Mohammed Salih.

In 1942 as part of Operation Torch, American forces attacked Safi in Operation Blackstone. During November 8-10, 1942 the Americans took control over Safi and its port and took relatively few casualties compared to the other operations at Casablanca and at Port Mehdia.

Climate

[edit]Safi has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh).

| Climate data for Safi (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.7 (99.9) |

40.5 (104.9) |

45.8 (114.4) |

46.4 (115.5) |

46.5 (115.7) |

42.6 (108.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

27.4 (81.3) |

46.5 (115.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.7 (65.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

25.5 (77.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

17.2 (63.0) |

14.8 (58.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.2 (28.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

2.3 (36.1) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55.8 (2.20) |

48.2 (1.90) |

41.2 (1.62) |

24.5 (0.96) |

14.8 (0.58) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0.6 (0.02) |

0.2 (0.01) |

5.0 (0.20) |

41.6 (1.64) |

68.7 (2.70) |

62.2 (2.45) |

366.0 (14.41) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.7 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 38.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 219.3 | 211.7 | 258.0 | 284.7 | 318.8 | 303.9 | 320.3 | 306.2 | 267.6 | 246.0 | 220.3 | 208.9 | 3,165.7 |

| Source 1: NCEI (sun, 1981-2010)[7] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

Population

[edit]The inhabitants are composed of Berber and Arab descendants.

The Berber origin is related to:[citation needed]

- The Berbers who lived in the region before the foundation of the city.

- The Berbers who came later from the Sous plains, south of the region.

The Arab origin is related to two tribes:[9]

- Abda: They descend from Banu Hilal and settled into the region in the twelfth century and spawned: Bhatra and Rabiaa.

- Ahmar: They descend from Maqil.

Safi also used to have a large Jewish community, more than 20% of the population,[citation needed] many of whom subsequently emigrated to France, Canada and Israel.

Economy

[edit]

In the early 20th century, the Moroccan potter Boujemâa Lamali established a pottery school in Safi, supported by the colonial administration. Since then pottery has been a mainstay of Safi's economy. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic there were 2,000 registered artisans working in the city's 212 workshops, and thousands more unregistered artisans.[10]

Sport

[edit]Football and rugby are popular sports in Safi. The local football team Olympic Safi have been competing in Morocco's premier football division, Botola, since 2004.

The Rugby Union team of the same name is one of Morocco's best, having won the "Coupe du Trône" several times. There also is a little Tennis Sport Club with a couple of fields (following the high road, beyond the Colline des Poitiers).

European cemetery

[edit]There is an abandoned European cemetery in Safi. Some of the marble decorations have been stolen from the richest tombs, including: Russian, Portuguese, Spanish (e.g. the Do Carmo family), Italian (e.g. the Bormioli family), French (e.g., the Chanel family), German and other European nationals. Some engravings identifying or memorializing the deceased have also been stolen. Although there are 19th century tombs present, most are of pre-independence (1956) 20th century origin.[citation needed]

Notable people

[edit]- Nadiya El Hani, Moroccan Journalist and Data Analyst.

- Mehdi Aissaoui, Moroccan Actor.[11]

- Meir Ben-Shabbat, Israel's National Security Adviser and Chief of Staff for National Security.[12] -->

- Edmond Amran El Maleh, Moroccan writer

- Mohamed Bajeddoub, Andalusian classical music singer

- Mohamed Benhima, former Prime Minister of Morocco, Minister of Education and Minister of the Interior.

- Brahim Boulami & Khalid Boulami, Moroccan Athlete

- Driss Benhima, CEO of Royal Air Maroc and president of Hawd Assafi, Safi-based non-profit organization

- Samy Elmaghribi, Moroccan musician

- Shayfeen, hip-hop duo

- Michel Galabru, French actor

- Ahmed Ghayby, member of the Moroccan football federation and president of Olympic Safi

- Abderrahim Goumri, Moroccan long-distance runner

- Zakaria El Masbahi, Moroccan basketball player

- Haja Hamounia, traditional chanteuse of Bedouin song

- Mohamed Mjid, former longtime president of the Royal Moroccan Tennis Federation

- Aharon Nahmias, Israeli politician

- Abu Mohammed Salih, 12th century religious leader

- Mohamed Reggab: film director

- Uri Sebag: Israeli politician

- Abraham Ben Zmirro: 15th century rabbi

- Abderrazak Hamdallah, professional footballer

- Yahia Attiyat Allah, professional footballer

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Tajine memorial

References

[edit]- ^ a b "POPULATION LÉGALE DES RÉGIONS, PROVINCES, PRÉFECTURES, MUNICIPALITÉS, ARRONDISSEMENTS ET COMMUNES DU ROYAUME D'APRÈS LES RÉSULTATS DU RGPH 2014" (in Arabic and French). High Commission for Planning, Morocco. 8 April 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Newitt, Malyn (November 5, 2004). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion 1400–1668. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 9781134553044.

- ^ Arabian American Oil Company, Aramco Services Company, Saudi Aramco (1991). Aramco world, Volumes 42-43. Aramco. p. 12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Basset, Henri & Ricard, Robert (1960). "Aṣfī". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 688–689. OCLC 495469456.

- ^ Cornell, Vincent J. (1998). Realm of the Saint: Power and Authority in Moroccan Sufism. University of Texas Press. pp. 326 (see note 80). ISBN 978-0-292-78970-8.

- ^ Itinéraire culturel des Almoravides et des Almohades: Maghreb et Péninsule ibérique (in French). Fundación El Legado Andalusí. 1999. p. 48. ISBN 978-84-930615-1-7.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010: Safi". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Safi Climate Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ MENNIS, Allal. "Safi ville.com". www.safi-ville.com.

- ^ "Why are Morocco's famed artisans paving roads in the desert?". The Economist. 2021-06-12. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ^ "Mehdi Aissaoui". IMDb. Retrieved Jan 5, 2021.

- ^ "Cabinet approves Meir Ben Shabbat as national security adviser". Ynetnews. Nov 12, 2017. Retrieved Jan 5, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Entry in Lexicorient

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 998, 999.

Safi, Morocco

View on GrokipediaGeography and Environment

Location and Physical Features

Safi is positioned on the Atlantic coast of western Morocco within the Marrakech-Safi region, at geographic coordinates approximately 32°17′N 9°14′W.[7] The city sits at an average elevation of 47 meters above sea level, with terrain rising from coastal plains to an inland plateau.[8] It lies midway between El Jadida to the north and Essaouira to the south along the coastline, approximately 200 kilometers southwest of Casablanca and 130 kilometers northwest of Marrakech.[9] The physical landscape surrounding Safi features rugged coastal scenery, including cliffs, beaches, and undulating plateaus shaped by geological formations such as Valanginian limestone and clay deposits, with evidence of Quaternary erosion in Cretaceous sediments.[10][11] To the southeast, the High Atlas Mountains rise, contrasting the relatively low-lying coastal zone and influencing regional drainage patterns toward the Atlantic.[8] The urban area extends along the shoreline and ascends the adjacent plateau, blending marine and elevated terrains.[7]Climate and Weather Patterns

Safi's climate is characterized by mild temperatures moderated by the Atlantic Ocean and the cold Canary Current, which flows northward along the coast, preventing extreme heat and contributing to higher humidity and fog in summer months.[12] The region exhibits semi-arid traits, with annual precipitation averaging approximately 241 mm (9.5 inches), concentrated in the winter months, supporting a Köppen classification of hot semi-arid (BSh) rather than fully Mediterranean (Csa), as rainfall falls below thresholds for the latter in some datasets.[13] [14] Average annual temperatures hover around 18°C (64°F), with low seasonal variation due to maritime influences.[15] Summers, from June to August, are short, warm, and arid, with average daily highs reaching 28°C (83°F) in August and lows around 20°C (68°F); rainfall is negligible, often 0 mm in July, though humidity peaks, leading to muggy conditions for up to 14 days in August.[13] Winters, spanning December to February, are cool and the wettest period, with highs of 18°C (64°F) in January and lows near 8°C (47°F); frost is rare due to coastal proximity.[16] The rainy season extends from mid-October to mid-April, peaking in November with about 46 mm (1.8 inches) and 5-6 rainy days, while the dry season dominates from May to September.[13] Winds are persistent year-round, averaging 12-13 mph (19-21 km/h) in summer peaks from the north, enhancing the cooling effect and contributing to coastal erosion patterns.[13] Extreme events, such as heavy winter storms or occasional heatwaves exceeding 35°C (95°F), occur infrequently but can intensify due to the region's exposure to Atlantic weather systems.[17]| Month | Avg. High (°C) | Avg. Low (°C) | Precipitation (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 18 | 8 | 40 |

| February | 18 | 9 | 40 |

| March | 19 | 10 | 30 |

| April | 20 | 11 | 20 |

| May | 21 | 13 | 10 |

| June | 23 | 15 | 5 |

| July | 24 | 17 | 0 |

| August | 25 | 18 | 0 |

| September | 24 | 17 | 5 |

| October | 23 | 15 | 30 |

| November | 20 | 12 | 46 |

| December | 19 | 9 | 40 |