Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tacticity

View on Wikipedia| Polymer science |

|---|

|

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Tacticity (from Greek: τακτικός, romanized: taktikos, "relating to arrangement or order") is the relative stereochemistry of adjacent chiral centers within a macromolecule.[1][better source needed] The practical significance of tacticity rests on the effects on the physical properties of the polymer. The regularity of the macromolecular structure influences the degree to which it has rigid, crystalline long range order or flexible, amorphous long range disorder. Precise knowledge of tacticity of a polymer also helps understanding at what temperature a polymer melts, how soluble it is in a solvent, as well as its mechanical properties.

A tactic macromolecule in the IUPAC definition is a macromolecule in which essentially all the configurational (repeating) units are identical. In a hydrocarbon macromolecule with all carbon atoms making up the backbone in a tetrahedral molecular geometry, the zigzag backbone is in the paper plane with the substituents either sticking out of the paper or retreating into the paper;[excessive detail?], this projection is called the Natta projection after Giulio Natta.[not verified in body] Tacticity is particularly significant in vinyl polymers of the type -H

2C-CH(R)-, where each repeating unit contains a substituent R attached to one side of the polymer backbone. The arrangement of these substituents can follow a regular pattern- appearing on the same side as the previous one, on the opposite side, or in a random configuration relative to the preceding unit. Monotactic macromolecules have one stereoisomeric atom per repeat unit,[not verified in body] ditactic to n-tactic macromolecules have more than one stereoisomeric atom per unit.[not verified in body]

The orderliness of the succession of configurational repeating units in

the main chain of a regular macromolecule, a regular oligomer molecule,

a regular block, or a regular chain.[2]

Definition

[edit]

Diads

[edit]Two adjacent structural units in a polymer molecule constitute a diad. Diads overlap: each structural unit is considered part of two diads, one diad with each neighbor. If a diad consists of two identically oriented units, the diad is called an m diad (formerly meso diad, as in a meso compound, now proscribed[3]). If a diad consists of units oriented in opposition, the diad is called an r diad (formerly racemo diad, as in a racemic compound, now proscribed[3]). In the case of vinyl polymer molecules, an m diad is one in which the substituents are oriented on the same side of the polymer backbone; in the Natta projection, they both point into the plane or both point out of the plane.

Triads

[edit]The stereochemistry of macromolecules can be defined even more precisely with the introduction of triads. An isotactic triad (mm) is made up of two overlapping m diads, a syndiotactic triad (also spelled syndyotactic[4]) (rr) consists of two overlapping r diads, and a heterotactic triad (rm) is composed of an r diad overlapping an m diad. The mass fraction of isotactic (mm) triads is a common quantitative measure of tacticity.

When the stereochemistry of a macromolecule is considered to be a Bernoulli process, the triad composition can be calculated from the probability Pm of a diad being m type. For example, when this probability is 0.25 then the probability of finding:

- an isotactic triad is Pm2, or 0.0625

- an heterotactic triad is 2Pm(1–Pm), or 0.375

- a syndiotactic triad is (1–Pm)2, or 0.5625

with a total probability of 1. Similar relationships with diads exist for tetrads.[5]: 357

Tetrads, pentads, etc.

[edit]The definition of tetrads and pentads introduce further sophistication and precision to defining tacticity, especially when information on long-range ordering is desirable.[citation needed] Tacticity measurements obtained by carbon-13 NMR are typically expressed in terms of the relative abundance of various pentads within the polymer molecule, e.g. mmmm, mrrm.[according to whom?]

Other conventions for quantifying tacticity

[edit]The primary convention for expressing tacticity is in terms of the relative weight fraction of triad or higher-order components, as described above. An alternative expression for tacticity is the average length of m and r sequences within the polymer molecule. The average m-sequence length may be approximated from the relative abundance of pentads as follows:[6]

Polymers

[edit]

Isotactic polymers

[edit]Isotactic polymers are composed of isotactic macromolecules (IUPAC definition).[7] In isotactic macromolecules, all the substituents are located on the same side of the macromolecular backbone. An isotactic macromolecule consists of 100% m diads, though IUPAC also allows the term for macromolecules with at least 95% m diads if that looser usage is explained.[3] Polypropylene formed by Ziegler–Natta catalysis is an example of an isotactic polymer.[8] Isotactic polymers are usually semicrystalline[9] and generally (but not exclusively) crystallize in a helical configuration.[10][11]

Syndiotactic polymers

[edit]In syndiotactic or syntactic macromolecules the substituents have alternate positions along the chain. The macromolecule comprises 100% r diads, though IUPAC also allows the term for macromolecules with at least 95% r diads if that looser usage is explained. Syndiotactic polystyrene, made by metallocene catalysis polymerization, is crystalline with a melting point of 161 °C. Gutta percha is also an example syndiotactic polymer.[12]

Atactic polymers

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

In atactic macromolecules the substituents are placed randomly along the chain. The percentage of m diads is understood to be between 45 and 55% unless otherwise specified, but it could be any value other than 0 or 100% if that usage is clarified.[3] With the aid of spectroscopic techniques such as NMR, it is possible to pinpoint the composition of a polymer in terms of the percentages for each triad.[13]

Polymers that are formed by free-radical mechanisms, such as polyvinyl chloride are usually atactic.[citation needed] Due to their random nature atactic polymers are usually amorphous.[citation needed] In hemi-isotactic macromolecules every other repeat unit has a random substituent.[citation needed]

Atactic polymers such as polystyrene (PS) are technologically very important.[citation needed] It is possible to obtain syndiotactic polystyrene using a Kaminsky catalyst,[14] but most industrial polystyrene produced is atactic.[citation needed] The two materials have very different properties because the irregular structure of the atactic version makes it impossible for the polymer chains to stack in a regular fashion: whereas syndiotactic PS is a semicrystalline material, the more common atactic version cannot crystallize and forms a glass instead.[citation needed] This example is quite general in that many polymers of economic importance are atactic glass formers.[citation needed]

Eutactic polymers

[edit]In eutactic macromolecules, substituents may occupy any specific (but potentially complex) sequence of positions along the chain.[citation needed] Isotactic and syndiotactic polymers are instances of the more general class of eutactic polymers, which also includes heterogeneous macromolecules in which the sequence consists of substituents of different kinds (for example, the side-chains in proteins and the bases in nucleic acids).[citation needed]

Effect on polymer properties

[edit]Tacticity has a significant effect on polymer crystallinity, and thus affects other properties that depend on crystallinity such as strength, melting point, and solubility. Isotactic and syndiotactic polymers have a more ordered structure and can form semicrystalline materials, while atactic polymers are generally amorphous (i.e. not crystalline) because their lack of order prevents them from packing into a crystal lattice.[9] Crystallinity generally leads to better mechanical strength, solvent resistance, and barrier properties, but amorphous polymers do not necessarily have poor mechanical properties and can have other advantages such as optical clarity.[9][15] As an example, atactic polypropylene is an amorphous polymer with a glass-transition temperature, Tg, of -27 °C, while isotactic polypropylene is crystalline with a Tg of -26 °C and a melting temperature, Tm, of 160 °C and syndiotactic polypropylene is also crystalline with a higher Tg of -4.3 °C and a lower Tm of 126 °C.[16] Isotactic polypropylene is strong and high-melting and so is widely used in a range of applications, while atactic polypropylene is soft and waxy and sees only limited use in adhesives and as an asphalt additive.[9]

Stereocontrolled polymerization

[edit]Polymers with controlled tacticity (i.e. not atactic) must be produced via some type of stereocontrolled polymerization. Stereocontrolled polymerizations have been demonstrated with a variety of chain-growth polymerization mechanisms, although stereocontrolled radical and cationic polymerizations are less common than stereocontrolled coordination and anionic polymerizations due to a lack of stereochemical definition at the propagating chain end.[17] Stereocontrolled polymerization of chiral monomers can also be enantioselective, meaning that one enantiomer of the monomer is selectively polymerized to give an isotactic polymer.[18] Depending on the origin of stereoselectivity, stereocontrolled polymerizations can be classified as polymer chain-end control or enantiomorphic site control.

Polymer chain-end control

[edit]In polymer chain-end control, the stereochemistry of the most recent monomer added to the polymer chain determines the stereochemistry of the next monomer added. In an isoselective polymerization, the next monomer to be inserted will have the same stereochemistry as the previous monomer, while in a syndioselective polymerization it will be the opposite. The stereoselectivity of a polymerization with polymer chain-end control is quantified by Pm and Pr, the probabilities of forming an m and r diad, respectively. An isoselective polymerization has a Pm approaching 1, while a syndioselective polymerization has a Pr approaching 1. When a stereoerror occurs (i.e. a monomer is added in the less favored orientation, such as the formation of a r diad in an isoselective polymerization), it is propagated, meaning that in an isoselective polymerization the substituents would switch from all being on one side of the polymer chain to all being on the other side.[19]

Enantiomorphic site control

[edit]In enantiomorphic site control, the stereochemistry of the next monomer added is instead determined by the stereochemistry of the catalyst. The stereoselectivity of a polymerization with enantiomorphic site control is often quantified by the site control selectivity α, the probability of adding a monomer with a certain absolute configuration. For an isoselective polymerization, an α value of 0 or 1 indicates a fully isotactic polymer while an α value of 0.5 indicates an atactic polymer. When a stereoerror occurs, it is corrected, meaning that (in an isoselective polymerization) substituents will return to being on the same side of the polymer chain that they were on before the error.[19]

Head/tail configuration

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2025) |

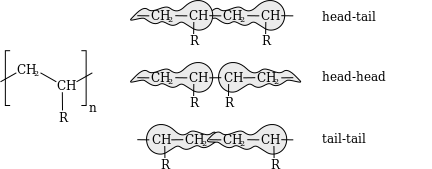

In vinyl polymers, the complete configuration can be further described by defining polymer head/tail configuration. In a regular macromolecule, monomer units are normally linked in a head to tail configuration such that β-substituents are located on alternating carbon atoms. However, it is possible for defects to form where substituents are placed on adjacent carbon atoms, producing a head/head tail/tail configuration, such as by recombination of two growing radical chains, or by direct head-head addition if steric effects are weak enough, such as in polyvinylidene fluoride.[20]

Techniques for measuring tacticity

[edit]Tacticity may be measured directly using proton or carbon-13 NMR. This technique enables quantification of the tacticity distribution by comparison of peak areas or integral ranges corresponding to known diads (r, m), triads (mm, rm+mr, rr) and/or higher order n-ads, depending on spectral resolution. In cases of limited resolution, stochastic methods such as Bernoullian or Markovian analysis may also be used to fit the distribution and predict higher n-ads and calculate the isotacticity of the polymer to the desired level.[21]

Other techniques sensitive to tacticity include x-ray powder diffraction, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS),[22] vibrational spectroscopy (FTIR)[23] and especially two-dimensional techniques.[24] Tacticity may also be inferred by measuring another physical property, such as melting temperature, when the relationship between tacticity and that property is well-established.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ Introduction to polymers R.J. Young ISBN 0-412-22170-5[page needed][full citation needed]

- ^ Jenkins, A. D.; Kratochvíl, P.; Stepto, R. F. T.; Suter, U. W. (1996). "Glossary of basic terms in polymer science (IUPAC Recommendations 1996)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 68 (12): 2287–2311. doi:10.1351/pac199668122287. S2CID 98774337. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ^ a b c d Fellows, Christopher M.; Hellwich, Karl-Heinz; Meille, Stefano V.; Moad, Graeme; Nakano, Tamaki; Vert, Michel (2020). "Definitions and notations relating to tactic polymers (IUPAC Recommendations 2020)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 92 (11): 1769–1779. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0409. hdl:11311/1163218.

- ^ Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged; Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Bovey, F. A. (1967). "Configurational Sequence Studies by N.M.R. And the Mechanism of Vinyl Polymerisation" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 15 (3–4): 349–368. doi:10.1351/pac196715030349. S2CID 59059402.

- ^ Paukkeri, R; Vaananen, T; Lehtinen, A (1993). "Microstructural analysis of polypropylenes produced with heterogeneous Ziegler–Natta catalysts". Polymer. 34 (12): 2488. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(93)90577-W.

- ^ IUPAC macromolecular glossary Archived 2008-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stevens, P. S. Polymer Chemistry: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Oxford Press: New York, 1999; pp 234–235

- ^ a b c d Odian, George (2004). Principles of polymerization (4th ed.). Hoboken (N.J.): J. Wiley & sons. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-471-27400-1.

- ^ Yashima, Eiji; Maeda, Katsuhiro; Iida, Hiroki; Furusho, Yoshio; Nagai, Kanji (2009-11-11). "Helical Polymers: Synthesis, Structures, and Functions". Chemical Reviews. 109 (11): 6102–6211. doi:10.1021/cr900162q. ISSN 0009-2665.

- ^ Auriemma, Finizia; De Rosa, Claudio; Corradini, Paolo (2004). "Non-Helical Chain Conformations of Isotactic Polymers in the Crystalline State". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 205 (3): 390–396. doi:10.1002/macp.200300126. ISSN 1521-3935.

- ^ Brandrup, Immergut, Grulke (Editors), Polymer Handbook 4th edition, Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1999. VI/11

- ^ Hatada, Koichi; Kitayama, Tatsuki (2004), Hatada, Koichi; Kitayama, Tatsuki (eds.), "Stereochemistry of Polymers", NMR Spectroscopy of Polymers, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 73–93, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-08982-8_3, ISBN 978-3-662-08982-8, retrieved 2025-06-30

- ^ Soga, Kazuo; Nakatani, Hisayuki (1990). "Syndiotactic polymerization of styrene with supported Kaminsky-Sinn catalysts". Macromolecules. 23 (4): 957–959. Bibcode:1990MaMol..23..957S. doi:10.1021/ma00206a010.

- ^ Hiemenz, Paul C.; Lodge, Timothy (2007). Polymer chemistry (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 496, 511. ISBN 978-1-57444-779-8.

- ^ Woo, Eamor M.; Chang, Ling (2011), "Tacticity in Vinyl Polymers", Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, doi:10.1002/0471440264.pst363, ISBN 978-0-471-44026-0, retrieved 2025-06-29

- ^ Teator, Aaron J.; Varner, Travis P.; Knutson, Phil C.; Sorensen, Cole C.; Leibfarth, Frank A. (2020-11-17). "100th Anniversary of Macromolecular Science Viewpoint: The Past, Present, and Future of Stereocontrolled Vinyl Polymerization". ACS Macro Letters. 9 (11): 1638–1654. doi:10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00664.

- ^ Xie, Xiaoyu; Huo, Ziyu; Jang, Eungyo; Tong, Rong (2023-09-29). "Recent advances in enantioselective ring-opening polymerization and copolymerization". Communications Chemistry. 6 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1038/s42004-023-01007-z. ISSN 2399-3669. PMC 10541874.

- ^ a b Coates, Geoffrey W. (2000-04-01). "Precise Control of Polyolefin Stereochemistry Using Single-Site Metal Catalysts". Chemical Reviews. 100 (4): 1223–1252. doi:10.1021/cr990286u. ISSN 0009-2665.

- ^ Vogl, O.; Qin, M.F.; Zilkha, A. (1999). "Head to head polymers". Progress in Polymer Science. 24 (10): 1481–1525. doi:10.1016/S0079-6700(99)00032-5.

- ^ Wu, Ting Kai; Sheer, M. Lana (1977). "Carbon-13 NMR Determination of Pentad Tacticity of Poly(vinyl alcohol)". Macromolecules. 10 (3): 529. Bibcode:1977MaMol..10..529W. doi:10.1021/ma60057a006.

- ^ Vanden Eynde, X.; Weng, L. T.; Bertrand, P. (1997). "Influence of Tacticity on Polymer Surfaces Studiedby ToF-SIMS". Surface and Interface Analysis. 25: 41–45. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9918(199701)25:1<41::AID-SIA211>3.0.CO;2-T.

- ^ Dybal, J.; Krimm, S. (1990). "Normal-mode analysis of infrared and Raman spectra of crystalline isotactic poly(methyl methacrylate)". Macromolecules. 23 (5): 1301. Bibcode:1990MaMol..23.1301D. doi:10.1021/ma00207a013.

- ^ Schilling, Frederic C.; Bovey, Frank A.; Bruch, Martha D.; Kozlowski, Sharon A. (1985). "Observation of the stereochemical configuration of poly(methyl methacrylate) by proton two-dimensional J-correlated and NOE-correlated NMR spectroscopy". Macromolecules. 18 (7): 1418. Bibcode:1985MaMol..18.1418S. doi:10.1021/ma00149a011.

- ^ Gitsas, A.; Floudas, G. (2008). "Pressure Dependence of the Glass Transition in Atactic and Isotactic Polypropylene". Macromolecules. 41 (23): 9423. Bibcode:2008MaMol..41.9423G. doi:10.1021/ma8014992.

Further reading

[edit]- Wandrey, Christine [Prof.] (2004-04-19). "Molecular Basis of the Structure and Behavior of Polymers, Part II: Chemistry and Structure of Macromolecules—Design of Polymer Chains" (PDF). EPFL.ch (polymer chemistry course materils). Lausanne, Switzerland: Laboratory of Polymers and Biomaterials, Dept. of Chemistry, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-04-19.

External links

[edit]Tacticity

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Early Discoverals

In the 1920s, Hermann Staudinger's pioneering research established the macromolecular nature of polymers, proposing that substances like rubber and polystyrene consist of long chains of repeating units rather than aggregates of small molecules, which provided the foundational framework for later recognition of stereoisomerism in synthetic polymers. Staudinger's experiments, including the synthesis and degradation of chain-like structures, demonstrated that polymer properties arise from their covalent backbone, setting the stage for understanding how stereochemical arrangements along these chains could influence material behavior, though explicit tacticity concepts emerged later.[4][5] During the 1940s and early 1950s, Carl E. Schildknecht conducted key experiments on the polymerization of vinyl ethers, observing distinct differences in properties between stereoregular and irregular forms. In 1947, using boron trifluoride as a catalyst, Schildknecht produced crystalline poly(vinyl isobutyl ether), which was later identified as isotactic due to its ordered stereochemistry, contrasting with the amorphous atactic variants that lacked crystallinity and exhibited softer, less rigid properties. These findings highlighted how tacticity affects solubility, melting points, and mechanical strength in synthetic polymers, marking one of the first empirical demonstrations of controlled stereoregularity in vinyl polymerizations.[6][7] Building on these observations, Giulio Natta achieved a breakthrough in 1954 by synthesizing isotactic polypropylene through the polymerization of propene using catalysts developed by Karl Ziegler, such as triethylaluminum combined with titanium compounds. This stereoregular form displayed high crystallinity and superior mechanical properties, like increased tensile strength and thermal stability, compared to atactic polypropylene, demonstrating the practical impact of tacticity on polyolefin materials and paving the way for industrial-scale production.[8][9]Key Advances and Recognition

In 1953, Karl Ziegler discovered the coordination polymerization of ethylene using a catalyst system composed of titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄) and triethylaluminum (AlEt₃), enabling the low-pressure synthesis of high-density polyethylene with linear chains and enhanced mechanical properties.[10] This breakthrough laid the foundation for stereospecific polymerization, as Ziegler recognized the potential for ordered monomer addition.[11] Building on Ziegler's work, Giulio Natta extended coordination catalysis to the synthesis of stereoregular polyolefins starting in 1954. Between 1954 and 1957, Natta and his collaborators achieved the first preparations of isotactic polypropylene and polystyrene using reduced titanium trichloride (TiCl₃) combined with aluminum alkyls (AlR₃), where the catalyst's active sites enforced regular stereochemistry in the polymer backbone. Natta introduced the terms "isotactic" for the configuration where all substituents are on the same side of the chain and "syndiotactic" for the alternating configuration.[12] In 1955, Natta reported the synthesis of isotactic polypropylene, marking the initial stereoregular polymer from propylene. Concurrently, he produced isotactic polystyrene, and by 1956, syndiotactic variants of both polypropylene and polystyrene, featuring alternating stereocenters, demonstrating versatile control over diad sequences like mm (isotactic) and mr (syndiotactic). For their pioneering contributions to stereospecific polymerization, which revolutionized polymer synthesis by enabling the production of tactic macromolecules previously limited to natural polymers, Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta were jointly awarded the 1963 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[11] In the 1980s, Walter Kaminsky and Hansjörg Sinn introduced metallocene catalysts, such as zirconocene derivatives activated by methylaluminoxane (MAO), which provided unprecedented precision in controlling polymer tacticity through tunable ligand environments and single-site active centers. These homogeneous systems allowed for the tailored synthesis of polyolefins with specific stereoregularities, including highly syndiotactic polypropylene, expanding beyond the heterogeneous Ziegler-Natta catalysts. In 2020, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) issued updated recommendations on definitions and notations for tactic polymers, refining terminology for stereosequences and diad structures to accommodate advances in synthesis and characterization, as detailed by Fellows and colleagues.[13]Definition and Concepts

Basic Definition

Tacticity refers to the stereochemical arrangement of substituents at stereogenic centers along the backbone of a polymer chain, particularly in vinyl polymers derived from monomers of the general form CH₂=CHR, where R is a substituent different from hydrogen.[14] In such polymers, the repeating unit is –CH₂–CHR–, and the carbon atom in the –CHR– group serves as a stereogenic (chiral) center, leading to potential stereoisomerism based on the relative orientations of the R groups.[14] This stereochemistry arises from the configurations at these adjacent chiral centers and is distinct from geometric isomerism, which involves cis-trans arrangements around double bonds in unsaturated polymers./03%3A_Isomerism) The fundamental building blocks for describing tacticity are diads, which are pairs of adjacent stereogenic centers. A meso diad (denoted as m) occurs when the two centers have identical relative configurations, resulting in a plane of symmetry, while a racemic diad (denoted as r) features opposite relative configurations.[13] These diads form the basis for higher-order sequences that define the overall tacticity.[13] Polymers are classified as tactic if they exhibit a regular, specific stereochemical arrangement of these diads along the chain, in contrast to atactic polymers, which have a random distribution of configurations.[13] The concept of tacticity was introduced by Giulio Natta in the mid-1950s during his pioneering studies on stereoregular polyolefins.[15]Stereosequences: Diads to Pentads

Stereosequences in polymers describe the relative stereochemical arrangements of consecutive chiral centers along the polymer chain, providing a framework for classifying tacticity from simple pairwise units to longer chains. The fundamental building block is the diad, which characterizes the configuration between two adjacent stereocenters. A meso diad (denoted m) features identical configurations at both centers, corresponding to isotactic placement, while a racemo diad (r) has opposite configurations, indicative of syndiotactic placement.[16] Heterotactic relationships emerge in mixed sequences but are more precisely defined in higher-order units.[17] Triads extend this to three consecutive stereocenters, denoted by combinations of diads such as mm (isotactic triad, two meso diads), rr (syndiotactic triad, two racemo diads), and mr or rm (heterotactic triad, mixed diads). Additional triad notations include mmm, mrr, and rrr for specific sequential patterns in extended analysis. In random or Bernoullian statistics, the distribution of these triads follows probabilistic models where the probability of a meso diad (Pm) equals the fraction of meso diads in the chain, with Pm = [mm] + ½[mr] and the racemo probability Pr = 1 - Pm; this yields triad fractions like [mm] = Pm2, [rr] = Pr2, and [mr] = 2PmPr.[18] Such statistics model atactic polymers where stereoplacement occurs independently at each center.[19] Tetrads involve four stereocenters (three diads), with examples including mmm, mmr, rmr, and rrr, allowing resolution of more subtle stereochemical variations. Pentads, spanning five stereocenters (four diads), provide even greater detail, such as mmmm for an isotactic pentad or rrrr for a syndiotactic pentad; these are commonly assigned via high-resolution techniques to quantify tacticity in vinyl polymers like polypropylene. A tacticity index can be expressed as the sum of isotactic and syndiotactic pentad fractions, ([mmmm] + [rrrr]) / total pentads, highlighting overall stereoregularity.[17] Higher-order sequences beyond pentads enable precise characterization of tacticity in irregular or defect-containing polymers, distinguishing fine deviations from ideal isotactic or syndiotactic structures. These sequence distributions influence polymer properties, such as crystallinity, by affecting chain packing efficiency.Descriptive Conventions

Descriptive conventions for tacticity provide standardized ways to quantify and denote the stereochemical arrangement in polymers beyond direct sequence analysis, often relying on spectroscopic data such as NMR to determine diad or triad fractions. These methods enable researchers to assess the degree of stereoregularity without exhaustive sequence mapping.[20] The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends specific prefixes to describe tacticity in polymer nomenclature: "i" for isotactic polymers, where all configurational units have the same relative configuration; "s" for syndiotactic polymers, featuring alternating configurations; and "a" for atactic polymers, characterized by random configurations. These prefixes are applied to the polymer name to indicate predominant stereochemistry, such as "i-poly(propylene)" for predominantly isotactic polypropylene, allowing concise communication of structural features.[21] Quantitative measures include the percent isotacticity, calculated as %mm = 100 × (meso diads / total diads), which expresses the proportion of isotactic (meso) diads relative to all diads (meso + racemic). This metric, derived from ^{13}C NMR analysis, provides a direct indicator of isotactic content; for instance, values above 95% signify highly isotactic material. A related tacticity index can quantify overall stereoregularity as I = (I + S) / (I + S + H), where I represents the fraction of isotactic diads, S the syndiotactic diads, and H the heterotactic diads, highlighting the combined regular (non-random) diad content.[20] Statistical models further describe tacticity by predicting triad probabilities from observed NMR data. The Bernoullian model assumes independent monomer additions, yielding triad fractions such as P_{mmm} = P_m^3 (where P_m is the meso probability), suitable for random stereochemistry. In contrast, the Markovian model (first-order) accounts for chain-end effects, with triad probabilities depending on the prior diad, such as P_{mmm} = P_{mm} × P_{m|m}, offering better fits for polymers with stereocontrol dependencies like those in biobased systems. These models are tested against experimental triad intensities to validate polymerization mechanisms.[22]Types of Tacticity

Isotactic Polymers

Isotactic polymers are characterized by a regular stereochemical configuration in which all substituent groups along the polymer backbone are positioned on the same side of the extended zigzag chain conformation. This arrangement results in a high degree of stereoregularity, consisting exclusively of meso diads (m), where adjacent chiral centers have identical configurations, leading to 100% m dyads and predominantly mmm triads in the chain microstructure. The uniform placement of substituents enables the adoption of a stable helical conformation, such as the 3/1 helix observed in many such polymers, which facilitates close packing and enhances intermolecular interactions.[23][24] A prominent example is isotactic polypropylene (iPP), produced primarily through Ziegler-Natta catalysis using titanium-based systems, which yields a highly crystalline material with a melting temperature of approximately 165°C and exceptional mechanical strength due to its ordered structure. Isotactic polystyrene (iPS), similarly synthesized via stereospecific polymerization, exhibits semi-crystalline properties with a melting point around 240°C, distinguishing it from its atactic counterpart by improved thermal stability and density. Another representative is isotactic poly(vinyl alcohol) (iPVA), obtained from the hydrolysis of stereoregular vinyl esters, which demonstrates enhanced crystallinity and higher melting point compared to atactic PVA, owing to its regular meso sequence that promotes hydrogen bonding in ordered domains. These polymers' high crystallinity arises from the ability of their regular chains to align into crystalline lattices, influencing thermal and mechanical behaviors.[25][26][27][28]Syndiotactic Polymers

Syndiotactic polymers are characterized by a regular alternation of substituents on opposite sides of the polymer backbone, resulting in a planar zigzag chain conformation that promotes crystallinity.[29] This alternating meso/racemic configuration distinguishes them from other tacticities, enabling distinct packing in the solid state.[30] The microstructure of ideal syndiotactic polymers consists of 100% racemic (rr) dyads, with predominant rrr triads, as determined by NMR spectroscopy.[31] This high stereoregularity was first achieved in the synthesis of syndiotactic polypropylene by Giulio Natta in 1955, using vanadium-based catalysts.[30] Modern production employs metallocene catalysts, such as C_s-symmetric zirconocenes, to yield highly syndiotactic materials with precise control over stereosequences.[32] Representative examples include syndiotactic polypropylene (sPP), which exhibits a melting temperature of approximately 130°C and a crystallinity of about 30%.[33] Another key example is syndiotactic polystyrene (sPS), featuring a glass transition temperature of approximately 100°C, similar to that of isotactic polystyrene, along with enhanced thermal stability.[3] These polymers often provide mechanical advantages, such as improved toughness, over their isotactic counterparts in applications requiring balanced stiffness and flexibility.[34]Atactic Polymers

Atactic polymers exhibit a random stereochemical configuration along their backbone, with no consistent pattern in the spatial arrangement of substituent groups relative to the chiral centers. This irregularity arises from an equal likelihood of forming either meso (m) or racemic (r) diads during polymerization, resulting in a disordered chain structure that inhibits molecular packing.[35] Statistically, unbiased atactic polymers follow a random distribution where the probability of a meso diad, denoted as , approximates 0.5, corresponding to a racemic mixture of configurations without preference for either stereoisomer.[18] Such randomness precludes long-range order, leading to predominantly amorphous materials that lack the crystalline domains found in more ordered counterparts.[36] Representative examples of atactic polymers include atactic polypropylene (aPP), which manifests as a viscous oil due to its inability to crystallize, and atactic polystyrene (aPS), a glassy amorphous solid serving as the base material for expanded foams such as Styrofoam.[37][38] These polymers are commonly synthesized via free radical polymerization, a process that propagates chain growth without mechanisms for stereochemical control, yielding the characteristic atactic microstructure.[39] Unlike isotactic or syndiotactic polymers with their regular stereosequences, atactic variants display no such periodicity, emphasizing the role of polymerization conditions in dictating stereochemical outcomes.[25]Eutactic Polymers

Eutactic polymers are tactic polymers characterized by perfectly regular stereosequences, including but not limited to isotactic and syndiotactic arrangements. Isotactic and syndiotactic polymers are specific examples of eutactic polymers. This regularity encompasses configurations such as strict alternation of meso (m) and racemo (r) diads, often termed heterotactic structures, where the chain exhibits a repeating pattern like all mr diads. The term "eutactic" originates from early nomenclature efforts in polymer stereochemistry during the 1960s, as outlined in IUPAC recommendations on steric regularity in high polymers.[40][35] In heterotactic eutactic polymers, the microstructure consists predominantly of 100% heterotactic triads, such as mrm and rmr, reflecting the alternating stereochemistry that distinguishes them from the uniform mm (isotactic) or rr (syndiotactic) triads. A representative case is heterotactic poly(methyl methacrylate (PMMA), achieved through stereoregular template polymerization using porous ultrathin films, resulting in highly selective mr diad formation for advanced optical materials.[35][41] Although eutactic polymers beyond isotactic and syndiotactic forms are rare in conventional synthesis due to the challenges in achieving such precise control, they hold significance in specialty applications requiring tailored microstructures, such as enhanced crystallinity or specific mechanical responses in niche composites.[42]Effects on Properties

Thermal and Crystallinity Effects

Tacticity profoundly influences the ability of polymer chains to pack regularly, thereby determining the degree of crystallinity and associated thermal transitions such as melting temperature (Tm) and glass transition temperature (Tg). In polymers with high stereoregularity, like isotactic and syndiotactic configurations, chains adopt ordered conformations that facilitate crystallization, leading to crystalline domains with distinct melting points typically in the range of 100-200°C. This regular packing enhances chain-chain interactions, resulting in higher crystallinity levels often exceeding 50%, which in turn elevates Tm due to the energy required to disrupt the ordered lattice.[43] For isotactic polymers, such as isotactic polypropylene (iPP), the all-meso diad configuration ([mm] ≈ 1) promotes helical conformations that pack into crystalline lattices, achieving crystallinities around 40-60% and a Tm of approximately 165°C. iPP predominantly crystallizes in the stable α-form (monoclinic) under typical conditions, though the metastable β-form (trigonal) can form with nucleating agents, influencing overall thermal behavior. Syndiotactic polymers exhibit similar trends but with distinct crystal structures; for syndiotactic polypropylene (sPP) with high racemic diad content ([rr] > 90%), crystallinity reaches 30-40%, and the equilibrium Tm is about 182°C, reflecting efficient packing in a helical zigzag conformation.[34][44] In contrast, atactic polymers lack stereoregularity, resulting in random side-group orientations that hinder close packing and yield amorphous structures with negligible crystallinity (<5%) and no observable Tm. For atactic polypropylene (aPP), the Tg is low, around 0°C, as the flexible chains remain in a rubbery state at room temperature due to disrupted ordering. The degree of crystallinity (X_c) correlates approximately with the meso diad fraction ([mm]), where X_c increases linearly with higher [mm] content, as demonstrated in polypropylene fractions. This functional dependence underscores how even partial isotacticity can induce semi-crystallinity. Eutactic polymers, featuring regular but non-isotactic or non-syndiotactic stereosequences, display variable thermal properties, often semi-crystalline with moderate Tm if the regularity supports packing, though specific examples remain less studied compared to tactic extremes.[45]Mechanical and Physical Properties

Isotactic polymers exhibit high tensile strength and stiffness due to their ordered chain structure, which enables efficient packing and load transfer. For example, isotactic polypropylene (iPP) typically displays a Young's modulus of approximately 1.5 GPa, reflecting its rigid crystalline domains that enhance resistance to deformation under stress.[46] In contrast, syndiotactic polymers offer superior impact resistance compared to their isotactic counterparts, attributed to a more balanced alternation of substituents that promotes ductility and energy absorption during fracture. This improved toughness in syndiotactic polypropylene makes it particularly suitable for applications requiring resilience to sudden loads.[47] Atactic polymers, lacking stereoregularity, adopt a disordered conformation that results in rubber-like elasticity and low modulus values, often below 0.1 GPa, leading to flexible, amorphous materials with minimal resistance to shear.[48] High-molecular-weight atactic polypropylene, for instance, behaves as an unvulcanized rubber at room temperature, providing extensibility but poor shape retention.[49] Tacticity also influences optical properties through structural anisotropy. Tactic polymers, with their aligned chains in crystalline regions, exhibit birefringence, where refractive indices vary by direction, enabling polarized light interactions.[50] Atactic polymers, being amorphous and isotropic, show no such directional dependence in light propagation.[50] Solubility differences arise from chain regularity affecting intermolecular interactions. Atactic polymers dissolve readily in common solvents like chloroform or toluene at ambient conditions due to their non-crystalline nature.[51] Tactic polymers, however, require elevated temperatures and solvents such as boiling xylene for dissolution, as their ordered structure resists solvent penetration.[52] These variations stem from crystallinity, which underpins the mechanical stiffness observed in tactic forms.Stereocontrol in Polymerization

Classical Mechanisms

In classical mechanisms of stereocontrol during polymerization, chain-end control refers to the process where the chirality of the stereogenic center at the growing polymer chain end dictates the stereochemistry of the incoming monomer addition.[53] This migratory mechanism influences the facial selectivity of monomer insertion, often leading to syndiotactic sequences in systems where racemic additions are favored over meso ones. In anionic polymerization of methacrylates, such as methyl methacrylate (MMA), chain-end control predominates, resulting in highly syndiotactic polymers when initiated with organolithium compounds in nonpolar solvents like toluene at low temperatures.[54] A seminal model for this behavior is the Coleman-Fox mechanism, which posits a two-state or multistate propagation involving tight ion pairs that preserve chain-end chirality, favoring syndiotactic placement through preferential racemic addition.[55] For instance, n-butyllithium initiation of MMA in toluene at -78°C yields poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) with over 90% rr triads, shifting from the atactic structures typical of radical polymerization to tactic ones via this control.[56] The mechanism explains stereo-block formation in mixed solvents, where solvent polarity modulates the ion-pair association, altering the syndiotactic content.[57] Quantitatively, chain-end control is modeled using propagation rate constants for meso and racemic additions, where the probability of racemic placement is given by: Here, is the rate constant for racemic (syndiotactic-favoring) addition, and for meso (isotactic-favoring) addition; in anionic systems like PMMA, , yielding .[53] This kinetic preference arises from steric interactions at the chiral chain end, minimizing energy for the unlike (racemic) configuration.[58] In contrast, enantiomorphic site control operates in coordination polymerizations where an achiral catalyst site temporarily adopts a chiral environment due to coordination with the growing chain, directing monomer approach to produce isotactic sequences.[59] Pioneered in Ziegler-Natta systems for propylene polymerization, this mechanism involves a vacant coordination site on the metal where the polymer chain and monomer bind, with the site's enantiotopic faces favoring one enantiomer's insertion, such as the re-face for isotactic polypropylene.[60] The Cossee-Arlman model describes this as a migratory insertion where the chain migrates to the monomer coordinated in the preferred chiral pocket, maintaining high isotacticity (mm triads >95%) without relying on the chain end's chirality.[61] This site-based stereocontrol was foundational to the development of Ziegler-Natta catalysis in the mid-20th century.[62]Catalyst-Based Methods

Catalyst-based methods for controlling tacticity in polymerization primarily involve Ziegler-Natta and metallocene systems, which enable the synthesis of stereoregular polyolefins such as isotactic and syndiotactic polypropylene.[30][63] Ziegler-Natta catalysts, typically consisting of titanium tetrachloride (TiCl₄) and triethylaluminum (AlEt₃), were pivotal in producing isotactic polyolefins like polypropylene.[30] These heterogeneous catalysts feature multiple active sites on a solid support, such as TiCl₃ or MgCl₂, leading to a distribution of stereospecificities that can yield polymers with varying tacticity depending on site populations and reaction conditions.[63] The mechanism relies on coordination of the monomer to titanium centers, where site control influences the stereoregular insertion of propylene units to favor isotactic sequences.[64] In the 1980s, metallocene catalysts revolutionized tacticity control by offering single-site homogeneity and ligand tunability. Unsubstituted bis(cyclopentadienyl)zirconium dichloride (Cp₂ZrCl₂) activated by methylaluminoxane (MAO) typically produces atactic polypropylene, while variations in metallocene symmetry and substitution enable precise synthesis of isotactic, syndiotactic, or atactic polypropylene. For instance, C₂-symmetric metallocenes, such as ethylenebis(indenyl)zirconium dichloride, produce highly isotactic polypropylene with over 99% mmmm pentad content, achieving superior stereoregularity compared to traditional Ziegler-Natta systems.[65] Advancements by James A. Ewen and Walter Kaminsky demonstrated the high activity of substituted metallocene/MAO catalysts, yielding stereoregular polymers under mild conditions.Modern Approaches

Modern approaches to tacticity control in polymerization have expanded beyond traditional coordination catalysis, incorporating radical processes, photochemical methods, and advanced computational tools to achieve precise stereoregulation post-2000. These techniques enable the synthesis of polymers with tailored microstructures, often under milder conditions, and have been pivotal in producing materials with enhanced properties for applications in biomedicine and advanced materials.[66] Stereospecific radical polymerization has emerged as a versatile strategy for controlling tacticity without relying on metal-based catalysts. By employing Lewis acids, such as Yb(OTf)3 or ZnCl2, to coordinate with the propagating radical and monomer, syndiotactic poly(methyl methacrylate (PMMA) can be synthesized with high syndiotacticity (rr dyad content up to 90%). Templating approaches, using preorganized macromolecular scaffolds, further enhance stereoselectivity by directing monomer addition through spatial constraints, as demonstrated in reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerizations yielding tacticities comparable to ionic methods. A 2024 review highlights these strategies as key to overcoming the inherent atacticity of free radical processes, enabling access to crystalline syndiotactic polymers.[66][66][66] Visible-light-induced organocobalt catalysis represents a light-mediated advancement for isotactic polymer synthesis. In this method, organocobalt complexes, such as cobalt porphyrins, mediate radical polymerization under visible light irradiation, promoting selective meso-meso (mm) dyad formation through reversible cobalt-carbon bond homolysis and stereocontrolled propagation. For instance, the polymerization of N,N-dimethylacrylamide yields highly isotactic polymers with mm dyad content exceeding 90%, resulting in crystalline materials with narrow polydispersity (Đ < 1.2) and controlled molecular weights up to 10 kDa. Reported in 2020, this approach leverages photoredox cycles to achieve living/controlled characteristics, marking the first synthesis of such crystalline isotactic polyacrylamides via radical means.[67][67][67] Ring-opening polymerization (ROP) tacticity control has been innovated using rotaxane-based catalysts, which exploit mechanical interlocking to enforce stereoselectivity. [68]Rotaxanes, featuring a cyclic component threaded onto a linear axle, enable dynamic conformational control that favors isoselective monomer insertion during ROP of lactide. This results in isotactic polylactides with high stereoregularity (Pm > 0.90), tunable by rotaxane design and solvent effects. Initially detailed in 2019, subsequent work has applied these systems to other cyclic esters like n-propylglycolide, achieving isotactic or heterotactic enrichment depending on conditions.[69] Computational models have revolutionized tacticity prediction and catalyst optimization in modern polymerization. Density functional theory (DFT) simulations predict pentad formation rates by calculating transition state energies for monomer insertion, revealing how ligand modifications influence stereoselectivity in olefin polymerizations; for example, DFT analyses show that bulky substituents on metallocene catalysts increase syndiotactic pentad (rrrr) probabilities by stabilizing si-face coordination. Machine learning (ML) approaches, including Bayesian optimization and neural networks, accelerate catalyst design by training on DFT-generated datasets to forecast tacticity outcomes, with 2025 trends emphasizing generative models for sustainable polymer synthesis that reduce experimental iterations by over 80%. These tools have enabled the virtual screening of thousands of catalysts, prioritizing those yielding >95% isotacticity.[70][70][71] A notable application of these advances is the self-assembly of isotactic poly(ethylene glycol)-block-polylactide (PEG-b-PLA) copolymers, synthesized via stereoselective ROP. Isotactic PLA segments promote ordered nanostructures, such as cylindrical micelles and vesicles, with morphologies dependent on tacticity; for instance, high isotacticity (Pm = 0.95) leads to elongated assemblies stable in aqueous media, enhancing drug encapsulation efficiency compared to atactic analogs. A 2025 study synthesized 22 variants, revealing that isotactic content correlates with reduced critical micelle concentration (CMC ~10^{-5} M) and improved hydrolytic stability, underscoring tacticity's role in biomedical self-assemblies.[72][72][72]Regioisomerism: Head-to-Tail Configuration

Definition and Occurrence

Regioisomerism in vinyl polymers refers to the constitutional arrangement of monomer units along the chain backbone, determined by the orientation of addition during polymerization, and is distinct from tacticity, which pertains to the stereochemical configuration at chiral centers. In head-to-tail (HT) addition, the predominant mode, the substituted carbon (head) of an incoming monomer bonds to the unsubstituted carbon (tail) of the growing chain, resulting in a regular, linear sequence where substituents alternate positions relative to the backbone. This configuration accounts for over 99% of linkages in most vinyl polymers, such as polystyrene and polyacrylates, due to favorable energetics and minimal steric or electrostatic repulsion.[73] In contrast, head-to-head (HH) addition occurs when the head of the incoming monomer bonds to the head of the chain end, creating a reversed orientation that introduces irregularities. HH linkages are rare defects in standard polymerizations, arising from occasional misalignments in monomer approach. For example, in free radical polymerization of vinyl chloride to form poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), HH additions occur at a low probability of approximately 0.2% (or 2 per 1000 monomer units). Such defects can be intentionally incorporated in certain copolymers or specialty polymers to tailor specific architectures, as seen in designed head-to-head polyolefins or poly(vinyl halides).[74] HH defects disrupt the regularity of the polymer chain by creating branch points—such as ethyl or methyl branches in PVC—or localized weak points where substituent groups cluster, potentially altering chain packing.[75] In notation, these are described as HT dyads (regular -CH2-CH(Z)-CH2-CH(Z)- sequences) versus HH dyads (-CH(Z)-CH(Z)-CH2-CH2-), where Z is the substituent; while regioisomerism itself does not introduce chirality, HH units can indirectly affect tacticity by modifying the local sequence that influences stereocontrol in subsequent additions.Structural and Property Impacts

Head-to-head (HH) defects in regioirregular polymers disrupt the regular chain packing, significantly lowering overall crystallinity by introducing structural irregularities that hinder the formation of ordered crystalline domains.[76] In tactic polymers such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVF2), these defects lead to a linear decrease in the equilibrium melting temperature (Tm), with typical HH content of 1-2 mol% reducing Tm by 10-20°C compared to defect-free analogs, as the defects act as exclusion points that limit lamellae thickness and perfection.[76] Similarly, in isotactic polypropylene (iPP), regio defects like 2,1-insertions cause a pronounced depression in Tm and crystallinity, with the effect being more severe than isolated stereodefects due to their ability to terminate helical segments and promote amorphous regions.[77] Mechanically, HH defects exacerbate brittleness by creating weak points in the polymer matrix that facilitate crack propagation and reduce ductility, particularly under stress or environmental exposure.[74] In polyvinyl chloride (PVC), HH linkages serve as initiation sites for dehydrochlorination during thermal degradation, accelerating the formation of conjugated polyene sequences that embrittle the material and lower its impact strength.[74] This degradation pathway contrasts with the more stable head-to-tail (HT) structure, where such defects are minimal, highlighting how regioirregularity amplifies vulnerability to processing or service conditions that promote chain scission and crosslinking. Representative examples illustrate these impacts in conjugated diene polymers. In polybutadiene, the predominantly HT-cis-1,4 configuration imparts high elasticity and resilience due to its ability to undergo reversible crystallization under strain, but HH defects introduce irregular linkages that promote unintended crosslinking, reducing elongation at break and shifting the material toward a more rigid, less recoverable network.[74] These defects can arise from oxidative or radical processes, altering the vulcanization behavior and compromising tire or rubber applications reliant on dynamic mechanical performance. The interplay between regioirregularity and tacticity amplifies structural disruptions, as HH defects more severely interrupt the regular helical conformations essential for crystallinity in tactic polymers.[78] In isotactic sequences, where chains adopt a 3/1 helical structure for packing, a single regio defect can terminate the helix propagation, leading to localized disorder that propagates further than equivalent stereodefects and results in broader melting transitions and reduced mechanical toughness.[79] This synergistic effect underscores why minimizing both regio- and stereo-defects is critical for optimizing polymer performance in high-stiffness applications like fibers or films.Characterization Techniques

Spectroscopic Methods

Spectroscopic methods, particularly nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and infrared (IR)/Raman spectroscopy, provide essential tools for determining the tacticity of polymers by resolving stereochemical sequences at the molecular level. These techniques exploit differences in chemical environments of atoms influenced by neighboring stereocenters, allowing assignment of diads, triads, and higher-order sequences such as pentads. Among them, 13C NMR is the most powerful for precise quantification due to its high sensitivity to stereochemistry, while 1H NMR offers complementary resolution for certain polymers, and IR/Raman detects tacticity through vibrational modes associated with conformational order. In 13C NMR spectroscopy, carbon atoms in the polymer backbone exhibit distinct chemical shifts based on meso (m) and racemic (r) diads, enabling tacticity analysis. For polypropylene (PP), the methine (CH) carbon resonates at approximately 28 ppm for m diads and 30 ppm for r diads, with higher magnetic fields (e.g., >100 MHz) resolving finer pentad sequences in the 27-31 ppm region. These assignments stem from two-dimensional techniques like INADEQUATE NMR, which correlate methine carbons with adjacent methyl groups to confirm stereosequence dependencies. Similar shift patterns apply to other vinyl polymers, where backbone carbons show stereosensitivity up to hexads. 1H NMR spectroscopy resolves tacticity through proton signals in the aliphatic region, though with lower resolution than 13C NMR due to signal overlap. In polystyrene, the methylene (CH₂) protons of the mm triad appear at about 1.8 ppm, distinct from mr (∼1.9 ppm) and rr (∼1.3 ppm) triads, allowing estimation of syndiotacticity in atactic samples. Spectral simulations and decoupling experiments refine these assignments, particularly for tactic-rich polymers where aromatic protons (∼6.5-7.2 ppm) show minimal stereosensitivity. IR and Raman spectroscopy detect tacticity indirectly via absorption bands linked to chain conformation and crystallinity. For isotactic polypropylene (iPP), the band at 998 cm⁻¹ in the IR spectrum corresponds to CH₃ rocking vibrations in the helical conformation, intensifying with isotactic sequence length (>10 units) and serving as a marker for syndiotactic or atactic fractions when compared to reference bands like 973 cm⁻¹. Raman spectra complement this by highlighting symmetric modes, such as the 808 cm⁻¹ band for syndiotactic PP, though IR is more routine for quantitative crystallinity assessment. Tacticity is quantified from these spectra by integrating peak areas corresponding to specific stereosequences, with 13C NMR offering the highest accuracy (e.g., m/r ratios from diad peaks in PP). Recent advances in 2D NMR, including HSQC and COSY variants, enhance resolution for complex copolymers by correlating proton-carbon shifts, enabling assignment of irregular sequences in materials like biobased polyesters without extensive model compound synthesis. These methods prioritize high-field instruments and relaxation agents for rapid, reliable analysis.Diffraction and Scattering Techniques

X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques are essential for identifying the crystal structures associated with polymer tacticity, particularly in semicrystalline materials like isotactic polypropylene (iPP), which typically adopts a monoclinic α-form with lattice parameters a = 6.65 Å, b = 20.80 Å, c = 6.50 Å, and β = 99.2°.[80] This form arises from the regular stereoregular arrangement enabling efficient chain packing, as opposed to atactic or syndiotactic variants that exhibit disordered or alternative polymorphs.[81] Crystallite sizes, which influence mechanical properties, are calculated using the Scherrer equation: where is the average crystallite size, is the shape factor (typically 0.9), is the X-ray wavelength, is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak, and is the Bragg angle; this method has been applied to tactic polypropylenes to quantify how stereoregularity affects domain perfection.[43] Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), a variant of XRD, provides insights into tacticity by analyzing the sharpness and position of diffraction peaks, where highly tactic polymers display narrower, more intense peaks due to enhanced crystallinity and ordered chain conformations compared to atactic counterparts, which show broader amorphous halos.[81] For instance, in hydrogenated poly(norbornene)s, isotactic samples yield orthorhombic structures with distinct sharp reflections, while atactic ones produce diffuse patterns indicative of poorer packing.[81] Similarly, in poly(1-octadecene), isotactic fractions exhibit sharper WAXS peaks corresponding to higher lamellar order, contrasting the broader profiles of atactic material.[82] Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) indirectly assesses tacticity through thermal transitions, with tactic polymers exhibiting distinct melting temperatures (Tm) above 100°C—such as 160–170°C for highly isotactic polypropylene—due to crystalline domains, whereas atactic variants remain amorphous without a Tm and display Tg values around -20°C.[83] Crystallinity degree, derived from enthalpy of fusion (ΔHf) via ΔHf = ∫(endotherm) / sample mass, correlates linearly with isotacticity, allowing estimation of stereoregularity from peak areas and onset temperatures.[45] For example, fractions with >92% isotacticity show Tm up to 169°C and crystallinities exceeding 45%, while lower tacticity yields depressed Tm and reduced order.[45] Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) probes nanoscale morphology in block copolymers with tacticity gradients, revealing domain sizes typically 10–100 nm that arise from stereochemical variations driving microphase separation.[84] In such systems, tacticity influences interdomain spacing, with more regular sequences promoting sharper interfaces and smaller, more uniform domains, as quantified by the scattering intensity peak position q* where domain size d ≈ 2π / q*.[84] This technique leverages neutron contrast from deuterium labeling to map tacticity-induced gradients, highlighting how syndio- or isotactic blocks alter phase behavior in copolymers like polystyrene-block-polybutadiene.[84]References

- Jun 28, 2017 · The tacticity of a polymer chain can have a major influence on its properties. Atactic polymers, for example, being more disordered, cannot ...Polymers and "pure substances" · Gallery of common synthetic... · Natural Polymers