Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bedford Square

View on Wikipedia

Bedford Square is a garden square in the Bloomsbury district of the Borough of Camden in London, England.

History

[edit]

Built between 1775 and 1783 as an upper middle class residential area, the square has had many distinguished residents, including Lord Eldon, one of Britain's longest serving and most celebrated Lord Chancellors, who lived in the largest house in the square for many years.[1] The square takes its name from the main title of the Russell family, the Dukes of Bedford, who owned much of the land in what is now Bloomsbury.[2]

The architect Thomas Leverton is known to have designed some of the houses, although he may not have been responsible for all of them.[3]

The building agreements for Bedford Square were signed by the trustees of the late Duke of Bedford and William Scott and Robert Grews, the builders, in 1776.[4] The first leases, for the entire west side (Nos. 28–39), were granted in November 1776. It seems unlikely that these dozen houses were built within 11 months so building probably started in 1775. Except for No. 46, the south side leases were granted in 1777, the east side in 1777 and 1778 (except Nos. 1 and 10), and the north side in 1781 and 1782 (except Nos. 24–27, granted in 1777). No. 11, which stands in Gower Street but has always been considered part of the square, had a separate building agreement of 1781 and was leased in June 1783.[5] This section was designed and built by Peter Matthias Van Gelder.[6]

The leases were granted by the estate once the shells were built but with internal finishing still to be carried out. No. 23 was the last house to be occupied, its owner moving in during the last quarter of 1784.[7]

The delay in finishing the building of the square can be put down in part to the shortage of money during the American War of Independence. Loans were granted by the trustees of the estate to the builders in order to finance building work from November 1777.[8]

Number 1

[edit]Number 1 Bedford Square is one of the great terraced houses of Georgian London and by far the best house in the square.[9] Sir John Summerson described it as a "particularly fine house" in 1945.[10]

Number 1 is almost certainly the work of the architect Thomas Leverton (1743-1824).[9] By his own admission Leverton designed the interiors of both Numbers 6 and 13 Bedford Square [11] and a number of details in those houses are repeated here. Although it sits outside the uniform symmetrical east side of the square, it has always been part of it and appropriately has always been numbered 1.[12] The house is distinguished by its central entrance,[13] rare for a three bay Georgian terraced house because such an arrangement required an ingenious plan to accommodate the staircase.[14] The front door leads into an entrance hall which is flanked by two separate spaces, an anteroom to the right and the fine stone staircase to the left. With the staircase in the front of the house, Leverton was able to design full width rooms to the rear half which took full advantage of the view over the established gardens of the British Museum.[15] There is a particularly fine decorative plaster ceiling in the first floor rear room.[16]

The house was threatened with demolition by the British Museum in 1860, along with Numbers 2 and 3 and the fourteen houses to the south in Bloomsbury Street, but nothing came of the museum's plans.[17] Then in the early 1930s a new building was planned which would stand only 20 feet from the rear elevation of Number 1.[17] The threat produced an article in Country Life that heralded the house as "a masterpiece of English architecture" and of "exceptional merit". Support came from Sir Edwin Lutyens, former resident of Number 31 Bedford Square for three years from 1915, who described the house as a "most interesting house ... of exceptional quality".[18] The British Museum's Duveen Gallery was built shortly before the Second World War [19] and today its plain brick flank wall is the view from the house rather than the gardens of the museum, which was such an important consideration in Thomas Leverton's original designs for the house.[17]

Conservation

[edit]Bedford Square is one of the best preserved set pieces of Georgian architecture in London, but most of the houses have now been converted into offices.[20] Numbers 1–10,[3] 11,[21] 12–27,[22] 28–38[23] and 40–54 are grade I listed buildings.[24]

Garden

[edit]The central garden remains private, but is opened to the public as part of the Open Garden Squares Weekend.[20] The square is Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[25]

Former occupants

[edit]Bedford College, the first place for female higher education in Britain, was originally located in (and named after) Bedford Square (No. 47).

- No. 1

- Sir Lyonel Lyde Bt., first occupier of the building for ten years until his death in 1791[3]

- No. 4

- Paul Weidlinger, structural engineer[26]

- No. 6

- Lord Eldon, Lord Chancellor[1]

- No. 8

- Frederick Warne & Norman Warne, publishers, of Frederick Warne & Co., who published the Beatrix Potter books[27]

- No. 10

- Samuel Lyde (brother of Sir Lyonel at No. 1)[3]

- Charles Gilpin, MP[28]

- No. 11

- Henry Cavendish, scientist[29]

- No. 13

- Harry Ricardo, engine designer, born at the house[30]

- No. 19

- New College of the Humanities, higher education institution founded by A.C. Grayling - 2012 to 2021[31]

- No. 22

- Johnston Forbes-Robertson, actor[32]

- No. 26

- National Council for Voluntary Organisations, 1928 – 1992[33]

- No. 30

- Jonathan Cape, publishing company[34]

- No. 35

- Thomas Hodgkin, physician, reformer and philanthropist[35]

- No. 35

- Thomas Wakley, founder of The Lancet[36]

- No. 36

- Thomas Wilkinson King, pathologist[37]

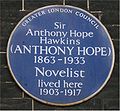

- No. 41

- William Butterfield, architect[38]

- Sir Anthony Hope Hawkins, novelist[39]

- No. 44

- Ottoline Morrell, socialite[40]

- Margot Asquith, wife of the Prime Minister H. H. Asquith[41]

- No. 48

- Elizabeth Jesser Reid, anti-slavery activist and founder of Bedford College for Women[42]

- No. 49

- Francis Walker, entomologist; before that Ram Mohan Roy, Indian scholar and reformer[43]

- No. 52

- Used as the contestants' house in the 2010 series of The Apprentice[44]

- No. 53

- Haydn Brown, surgeon and psychotherapist[45][46]

See also

[edit]Other squares on the Bedford Estate in Bloomsbury included:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Riley, W Edward; Gomme, Laurence (1914). "'Nos. 6 and 6A, Bedford Square', in Survey of London: Volume 5, St Giles-in-The-Fields, Pt II". London. pp. 154–156. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ Riley, W Edward; Gomme, Laurence (1914). "'Bedford Square (general)', in Survey of London: Volume 5, St Giles-in-The-Fields, Pt II". London. pp. 150–151. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d Historic England. "Nos 1 to 10 and attached railings (1272304)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 31. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 40. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 by Rupert Gunnis p.407

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 41. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 41 and Appendix 2, p156. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ a b Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 76. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Summerson, John (1945). Georgian London. London: Pleiades Books. p. 148.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 91, letter to the Duke of Bedford dated 17 July 1797. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 74. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. colour plate I. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 77. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. colour plate VII. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ a b c Byrne, Andrew (1990). Bedford Square: an architectural study. London and Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: The Athlone Press. p. 89. ISBN 0 485 11386 4.

- ^ "1, Bedford Square, London, The Residence of Mr G. D. Hobson, M.V.O.". Country Life. London. 6 February 1932. p. 189.

- ^ "Annex IV: The Parthenon Sculptures". www.parliament.uk. UK Parliament. March 2000. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

The Duveen Gallery was ... completed in 1938 ...

- ^ a b "Bedford Square". www.opensquares.org. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Number 11 and Attached Railings (1272315)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Numbers 12-27 and Attached Railings (1244546)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Numbers 28-38 and Attached Railings (1244548)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Numbers 40-54 and Attached Railings (1244553)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ Historic England, "Bedford Square (1000245)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 19 November 2017

- ^ Weidlinger, Tom. "Beauty, art and the shape of things to come". restlesshungarian.com. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Owen, William Benjamin (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 594–595.

- ^ 10, Bedford Square is the address of his letter to the Editor of The Times, Tuesday, 26 October 1858; p. 4; Issue 23134; col E. Letters before that date are from 5, Bishopsgate without.

- ^ "Cavendish, Henry (1731-1810)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Ricardo, Sir Harry (1885-1974)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "New College of the Humanities to expand with new central London campus in 2021". New College of the Humanities. 13 October 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "Johnston Forbes-Robertson black plaque in London". Blue plaques. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "National Council for Voluntary Organisations". National Archives. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Jonathan Cape –". Harrington Books. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Hodgkin, Thomas (1798-1866)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Wakely, Thomas (1795-1862)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Dr. T. W. King (1809–47)". Nature. 159 (4037): 365. 15 March 1947. doi:10.1038/159365a0.

- ^ "Butterfield, William (1814-1900)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Hawkins, Anthony Hope (1863-1933)". English Heritage. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Lady Ottoline Morrell". Open Plaques. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Margot Asquith, socialite and author, wife of Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith. Autograph Note Signed ('Margot Oxford') acknowledging receipt of a letter and a book". Richard Ford Manuscripts. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Elizabeth Jesser Reid". Blue Plaques. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ The Annals and Magazine of Natural History. Vol. 18. 1846. p. 143. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Bedford Square". Urban75. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Haydn Brown, Deceased" (PDF). The London Gazette. 27 December 1938. p. 8267.

- ^ "Who Was Who in Bedford Square?". Ukwhoswho.com. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

External links

[edit]Blue plaques

[edit]A number of houses have blue plaques recording famous residents:

-

Harry Ricardo

-

Thomas Hodgkin

-

Thomas Wakley

-

Anthony Hope Hawkins

-

William Butterfield

-

Elizabeth Jesser Reid

-

Ram Mohan Roy

-

Lord Eldon

51°31′08.08″N 00°07′48.39″W / 51.5189111°N 0.1301083°W

- Plaquemap.com London blue plaque scheme — For exact location of these plaques within the square.

Bedford Square

View on GrokipediaLocation and Description

Geographical Context

Bedford Square is situated in the Bloomsbury district of central London, within the London Borough of Camden.[1] It lies at approximately 51°31′07″N 0°07′43″W, placing it on relatively level ground east of Tottenham Court Road.[4] The square occupies a prominent position in the urban fabric of Bloomsbury, with key landmarks in close proximity that enhance its cultural and academic significance. To the south lies the British Museum, a major global institution housing extensive collections of art and history, while University of London buildings, including facilities for institutions like Royal Holloway, are scattered throughout the surrounding area.[5][6] Adjacent to the east is Russell Square, one of London's largest garden squares, providing a direct link to the broader network of green spaces and educational hubs in the district.[6] As part of the historic Bedford Estate, long owned by the Russell family—holders of the title Duke of Bedford—the square's development and naming reflect the estate's influence over Bloomsbury's planned expansion since the late 17th century.[7] This estate ownership shaped the area's layout, integrating Bedford Square into a cohesive grid of residential and institutional spaces. The surrounding street layout further defines its boundaries, with Bloomsbury Street to the north, Gower Street along the eastern edge, and Bedford Avenue to the south, facilitating connectivity to major thoroughfares like New Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road.[1]Physical Layout and Features

Bedford Square is a rectangular garden square, characteristic of 18th-century London urban planning, enclosed on all four sides by terraced houses.[1] The central garden, covering approximately 1 hectare, features a large oval lawn surrounded by a perimeter path, mature London plane trees providing shade and screening, and shrubberies including species such as laurustinus, holly, laurel, privet, and sorbus.[1][8] A restored hexagonal summerhouse stands on the west side, offering shelter, while herbaceous borders and small grass areas add to the landscaped character; the garden is enclosed by late 18th-century cast-iron railings with spearhead finials.[1][8] The surrounding houses form a uniform four-sided terrace of 54 Georgian townhouses, predominantly three stories high with attics and basements, constructed in yellow stock brick with tuck-pointed detailing.[9][10][1] The facades exhibit classical symmetry, with cast-iron balconies at the first-floor windows on many properties, and recessed doorways featuring Coade stone decorations, round-headed arches, enriched imposts, and radial fanlights; central houses on each side often include pediments and pilasters for emphasis.[9] Basements are railed with cast-iron enclosures bearing urn or torch-flambé finials, originally providing light and access to service areas.[9] Access to the square is provided through four main entrances from adjacent streets—Bedford Avenue to the south, Bloomsbury Street to the north, Gower Street to the east, and Thornhaugh Street (formerly Bedford Street) to the west—with the north and south entrances featuring late 18th-century wrought-iron gates, enhancing the enclosed, pedestrian-oriented environment.[1] The garden remains under the stewardship of the Bedford Estate, accessible primarily to keyholders among local residents and businesses.[11]Historical Development

Origins and Construction

Bedford Square was developed as part of the expansion of the Bedford Estate in Bloomsbury, with initial proposals dating to 1763 under John Russell, the fourth Duke of Bedford, who envisioned it as "Bedford Circus" inspired by Bath's Royal Crescent. Following the Duke's death in 1771, his trustees, led by chief agent Robert Palmer, advanced the project to transform former fields into a prestigious residential enclave.[12][1] Construction commenced in 1775 and spanned until 1780, with building agreements signed in 1776 between the trustees and builders William Scott and Robert Grews, who undertook the speculation in association with architect Thomas Leverton. Leases for the 54 uniform terraced houses were granted progressively from 1776 to 1783, reflecting the leasehold system typical of London estate development. Leverton is credited with designing the overall layout and specific properties, including Nos. 1, 10, and 52–54, emphasizing symmetry around a central garden.[10][1][12] The project faced delays due to the American War of Independence (1775–1783), which triggered financial shortages and a broader slump in building activity, complicating large-scale urban schemes like this one. Intended for upper-middle-class residents, the square sought to replicate the ordered elegance of country estates in a metropolitan setting, with houses occupied progressively from the late 1770s onward. It derives its name from the Bedford family, the longstanding landowners of the estate.[10][12][1]Evolution Through the Centuries

In the 19th century, Bedford Square transitioned from an exclusively residential enclave for the elite to a mixed-use area incorporating institutional functions, reflecting broader urbanization in Bloomsbury. A key example was the establishment of Bedford College at No. 47 in 1849 by Elizabeth Jesser Reid, marking it as the first higher education institution for women in the United Kingdom and symbolizing advancing opportunities for female scholars amid Victorian social changes.[13] The college operated from this location until 1874, when it relocated to larger premises in York Place, leaving a legacy of educational innovation in the square's evolving landscape.[14] Following World War I, Bedford Square saw increasing commercial adaptation, with many houses converting to offices and professional societies, driven by London's growing administrative needs and the square's central location. Impacts from World War II were minimal owing to its inland position away from primary bombing targets, though minor bomb damage necessitated repairs to individual properties, preserving the overall Georgian fabric.[5] Mid-20th-century preservation efforts intensified in the 1950s and 1960s, as the Georgian Group, founded in 1937, led campaigns against widespread office conversions that threatened the square's residential character and uniformity; these advocacy drives successfully influenced policy to retain its historical scale. By the 1970s, vehicular traffic through the square was restricted to protect the central garden and pedestrian environment, further solidifying its status as a conserved urban oasis.[15]Architectural Characteristics

Overall Design Principles

Bedford Square exemplifies the Georgian neoclassical style, characterized by a commitment to symmetry, proportion, and classical elegance that draws heavily from Palladianism, the architectural movement inspired by Andrea Palladio's interpretations of ancient Roman and Renaissance designs. This influence is evident in the square's aim to replicate the grandeur of rural estates within an urban setting, creating villa-like residences that emphasize balanced facades and harmonious proportions to foster a sense of refined domesticity amid the city's density.[10][16] The uniformity of the square's design principles ensures a cohesive visual identity, achieved through standardized facades constructed primarily from yellow stock brick with contrasting stucco dressings and wrought-iron railings that delineate private spaces. Central pavilions on each side introduce a subtle hierarchy, marking focal points while maintaining overall consistency, a deliberate choice to project unity and social order in late-18th-century London.[10] At its core, the layout philosophy adopts the garden square model, a hallmark of Georgian urbanism that prioritizes a communal central green space enclosed by residential terraces, blending private gardens with semi-public access to promote resident well-being and social cohesion. Architect Thomas Leverton played a pivotal role in this vision, overseeing balanced elevations across the 53 houses and incorporating subtle variations—such as pediments on corner properties—to prevent visual monotony while preserving the ensemble's integrity.[10][16] In the broader urban planning context, Bedford Square formed part of Bloomsbury's methodical grid expansion during the 1770s and 1780s, spearheaded by the Bedford Estate to impose regularity on former pasturelands, in stark contrast to the haphazard, irregular developments that had previously characterized much of London's growth. This planned approach, influenced by the 1774 Building Act, underscored a shift toward disciplined, aesthetically unified neighborhoods that elevated the area's status as a desirable residential enclave.[10][17]Notable Structural Elements

Bedford Square's buildings consist of three- to four-storey terraced houses over basement areas, unified by yellow stock brick facades with evidence of tuck pointing and plain stucco bands at the first floor.[9][18][19] Doorcases are a defining feature, typically recessed and round-headed with Coade stone vermiculated voussoirs, mask keystones, enriched impost bands, cornice-heads, side lights, and radial patterned fanlights; representative examples include those at Nos. 1-10 on the east side.[9] Ionic columns or pilasters often flank these entrances, rising through the first and second storeys, as seen at No. 6 (with five pilasters) and Nos. 46-47 (supporting pediments with swag and roundel enrichments on the tympanum).[9][19] No. 1 stands out with its grander triumphal arch-style entrance incorporating niches and crossed arrows, designed by Thomas Leverton as a showhouse.[9][10] Architectural variations across the square add subtle distinction while preserving overall harmony. The north side (Nos. 40-54) features slightly taller four-storey houses in some cases, with gauged brick flat arches over recessed sash windows and cast-iron balconies at the first floor on Nos. 40-47 and 53.[19] Corner pavilions, such as No. 21 on the west side, include prostyle porches with Greek Doric columns and full-height segmental bays.[20] The west side (Nos. 21-25 and 28-38) shows further diversity, with stuccoed facades and banded rustication on ground floors at Nos. 22-23, 25, and 32, alongside Ionic pilasters and pediments at No. 32.[20][18] Rear elevations are simpler, prioritizing functionality with full-height bowed or canted bays for natural light and access to adjacent mews, as evident in Nos. 28-38 and 40-54.[18][19] The central garden integrates seamlessly with the surrounding structures through perimeter cast-iron railings with spearhead finials and bracketed design, which frame outward views from the houses while enclosing the private oval lawn.[21][1] These railings, dating to 1776-1781, complement the area railings with urn or torch-flambé finials attached to the houses, creating a cohesive boundary that enhances the square's enclosed, palace-like quality.[21][9] Perimeter shrubberies of laurustinus, holly, laurel, and privet, along with two large semicircular herbaceous beds on the north and south sides, provide screening and soften the transition to the built environment, while mature plane trees scattered across the lawn offer dappled views into the space.[1] A single perimeter path encircles the lawn, historically supplemented by radial paths that were removed in the late nineteenth century.[1] Unique elements underscore the square's refined detailing. Subtle brickwork patterns, such as rustication and gauged arches, recur throughout, paired with uniform recessed sash windows (often with glazing bars) that emphasize verticality and light.[9][18] The use of yellow stock bricks, compliant with the standardized construction of the 1774 Building Act and sourced locally, has resulted in a patinated surface that enhances the ensemble's historic patina and cohesion.[10][9]Conservation and Preservation

Listing and Protection Status

Bedford Square's buildings are predominantly Grade I listed on the National Heritage List for England, the highest level of protection for architectural and historic interest in the United Kingdom, with number 39 holding Grade II status. This designation covers the terrace in grouped entries issued by Historic England: numbers 1–10 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade I); number 11 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade I); numbers 12–27 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade I); numbers 28–38 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade I); number 39 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade II); and numbers 40–54 and attached railings, listed on 24 October 1951 (Grade I).[9][22][23][18][24][19] The Grade I listings recognize the square as an exemplary instance of intact 18th-century urban planning, with terraces constructed between 1775 and 1783 primarily in yellow stock brick to designs possibly by Thomas Leverton or Robert Palmer for the Bedford Estate. Criteria for Grade I status emphasize the buildings' special architectural interest, including features such as Coade stone doorcases, cast-iron balconies, slate mansard roofs, and well-preserved original interiors with stone staircases and ornate plasterwork, alongside their historic associations with notable residents and institutions. Number 39 shares similar architectural features but is designated Grade II.[9][23][18][19][22][24] Protection is enforced under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, which safeguards the structures, attached railings, and curtilage elements predating 1 July 1948 from demolition, alteration, or extension without consent. The London Borough of Camden Council administers planning permissions for any modifications, ensuring proposals preserve or enhance the buildings' significance, as seen in applications for listed building consent reviewed by the authority.[9][23][25] The Bedford Estate, retaining ownership of much of the square, collaborates on maintenance and development, adhering to these restrictions to uphold the site's integrity.[10] The square forms part of the Bloomsbury Conservation Area, designated on 1 December 1968 to preserve the character of Georgian Bloomsbury, including Bedford Square's cohesive streetscape.[26] No major delistings have occurred since initial designations, maintaining Grade I coverage for most of the terrace. Advocacy organizations, including the Georgian Group—founded in 1937 to protect Georgian-era buildings—and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, established in 1877, have supported preservation efforts for Bloomsbury's heritage, contributing to the broader framework that secured and sustains these protections.[27][28][5]Garden and Green Spaces

The central garden of Bedford Square was laid out between 1776 and 1780 as a private communal space for the square's residents, forming an integral part of the Bedford Estate's Bloomsbury development.[1] This pioneering design, likely influenced by architects such as Thomas Leverton, William Scott, and Robert Grews, features an oval-shaped central lawn surrounded by a perimeter path, shrubberies, and herbaceous borders, establishing a model for London's Georgian garden squares with imposed architectural uniformity.[1] Mature London plane trees (Platanus × acerifolia) dominate the canopy, providing shade and screening, while shrub groups including laurustinus, holly, laurel, privet, and sorbus enhance the borders alongside two semicircular flower beds and scattered benches.[1][8] The garden received Grade II* listing on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens in 1987 from Historic England, recognizing its special historic interest as one of the earliest and finest surviving examples of a late 18th-century London square garden.[1] This designation encompasses the landscape's core elements, including the original layout with its oval lawn and perimeter path, the late 18th-century cast-iron railings (separately Grade II listed) enclosing the space, and a restored hexagonal summerhouse dating to the 19th century on the west side.[1] Access to the garden is restricted to key-holding residents and approved businesses in the WC1 postcode area through a subscription scheme managed by the Bedford Estate, which charges an annual fee of £80 plus VAT for individuals.[11] However, it opens to the public annually during London Open Gardens weekend, typically held in early June, allowing visitors to explore the space from 10:00 to 16:00 on Saturday and Sunday with picnics permitted.[8] The garden remains largely faithful to its original design, with minimal alterations following a re-landscaping in the 1870s that removed serpentine paths and entrance gates in 1893, preserving its role as a serene, enclosed haven amid the urban setting.[1] Maintenance of the garden is overseen by a dedicated team of gardeners from the Bedford Estate, who focus on conserving its historic character while ensuring year-round accessibility and enjoyment for key holders.[11] The estate's approach emphasizes low-maintenance practices that support local wildlife, including through shrub and perennial selections that encourage pollinators and biodiversity in the borders and understory.[29]Notable Occupants and Uses

Historical Residents

Bedford Square attracted a distinguished array of residents from the late 18th to the 20th century, many of whom were prominent in politics, science, law, and the arts, reflecting its status as a desirable address for the upper-middle-class professional elite.[10] Early occupants included merchants and lawyers tied to Britain's colonial economy, while later residents encompassed scientists and reformers, underscoring the square's role in fostering intellectual and professional networks.[1] Among the most notable early residents was Sir Lyonel Lyde, a baronet and merchant who occupied No. 1 from its completion around 1776 until his death in 1791; as the first tenant, he exemplified the square's initial appeal to wealthy City figures.[30] In the 1790s, Lord Eldon, the Lord Chancellor under George III, resided at No. 6, where he hosted key political meetings, including a famous 1812 interview with the Prince Regent that influenced wartime policy; his tenure from 1800 to 1819 highlighted the square's proximity to Westminster power centers.[3][31] The scientist Henry Cavendish, renowned for discovering hydrogen in 1766 and measuring the Earth's density, used No. 11 as his London library from the 1780s until his death in 1810, conducting much of his reclusive research there while maintaining a separate laboratory in Clapham.[32][33] Scientific and medical luminaries continued to gravitate to the square in the 19th century. At No. 35, physician Thomas Hodgkin, who described the lymphatic condition now bearing his name, lived from 1825 to 1837, advancing pathology through his work on morbid anatomy.[34] His contemporary, reformer Thomas Wakley, founder of the medical journal The Lancet in 1823, also resided at No. 35 from 1827 to 1830, using it as a base to campaign against medical corruption and professional monopolies.[35] No. 10 housed other scientists in the mid-19th century, contributing to the square's reputation as a hub for empirical inquiry amid London's burgeoning scientific community.[36] Institutions also played a pivotal role in the square's history. Bedford College, founded in 1849 at No. 47 by Elizabeth Jesser Reid, was Britain's first higher education institution for women, offering non-sectarian courses in sciences, languages, and history; it remained there until the 1860s, expanding to adjacent properties like No. 48 before relocating to Regent's Park in 1913, pioneering female access to university-level study.[37] Publishers such as Frederick Warne & Co., with Warne himself at No. 8 until his death in 1901, established offices in the square during the late 19th century, capitalizing on its central location for the growing book trade.[38] The 20th century brought actors, socialites, and engineers to the square. Actor Johnston Forbes-Robertson, celebrated for his Shakespearean roles, lived at No. 22 in the early 1900s, embodying the shift toward creative professions. Socialite Lady Ottoline Morrell hosted influential literary salons at No. 44 from 1906 to 1920, entertaining figures like Bertrand Russell and D.H. Lawrence, which amplified the square's cultural vibrancy.[39] Engineer Sir Harry Ricardo, born at No. 13 in 1885, developed innovative internal combustion engines pivotal to early aviation and automotive design.[40] Several blue plaques mark these legacies. English Heritage installed one for Cavendish at No. 11 in 1997, recognizing his foundational contributions to chemistry and physics.[33] Plaques at No. 35 honor Hodgkin (installed 2003) and Wakley (2003), while one at No. 13 for Ricardo dates to 2005, and No. 6 for Eldon to 1907, preserving the square's ties to law, medicine, and engineering.[34][35][40] Overall, Bedford Square's residents mirrored the era's professional ascendance, with many linked to politics, science, and law, fostering a milieu of intellectual exchange until institutional shifts in the mid-20th century.[10]Modern Institutions and Events

In the 21st century, Bedford Square has evolved into a prominent hub for professional and cultural activities, primarily occupied by offices in publishing, fashion, finance, and education. Publishers such as Yale University Press maintain their London headquarters at No. 47, while Bloomsbury Publishing operates from No. 50, underscoring the square's role in the literary and academic sectors.[41][42] Fashion houses and financial service providers also lease space here, contributing to a vibrant ecosystem of creative and commercial enterprises.[43] The Architectural Association School of Architecture, the UK's oldest independent architecture school, is based at No. 36, fostering innovative design education and public engagement.[44] Similarly, Sotheby's Institute of Art occupies No. 30, providing postgraduate programs in art business and connoisseurship within the historic Georgian setting.[45] Educationally, the square hosted the New College of the Humanities from 2012 to 2021 at No. 19, where it offered undergraduate degrees in humanities subjects before relocating to a larger campus. Ongoing connections to the University of London persist through institutions like the Bloomsbury Institute, which uses Bedford Square facilities for business and law programs, reinforcing the area's academic legacy.[46] Bedford Square hosts notable annual events that highlight its cultural vitality. The London Open Gardens weekend, organized by the London Parks & Gardens Trust, opens the private gardens to the public each June, allowing visitors to experience the square's green spaces amid Bloomsbury's heritage.[47] In 2024, the Architectural Association's Emergent Technologies and Design program unveiled the DensiFlora pavilion on the square's southwest corner, a collaborative installation with Populous exploring sustainable architecture through rattan canes and robotic fabrication, displayed from November to December.[48] A significant literary event occurred on June 11, 2025, when Queen Camilla delivered a speech celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Women's Prize for Fiction in Bedford Square Gardens, joined by shortlisted authors and past winners to honor women's contributions to literature.[49] Commercially, the square features minimal residential use, with most buildings repurposed for offices in creative industries like publishing and design. Properties such as Nos. 19–21 have undergone renovations for mixed-use purposes, including high-end workspaces that preserve Georgian features while accommodating modern professional needs.[50][51] The square's pedestrian-friendly layout, with its central gardens and surrounding pavements, enhances accessibility for public activities, including guided literary tours of Bloomsbury that feature stops at Bedford Square to explore its connections to authors like Virginia Woolf. Art exhibitions, such as those at the Architectural Association and Sotheby's Institute, further invite visitors to engage with contemporary displays in this historic environment.[52][48]Cultural Significance

Literary and Artistic Connections

Bedford Square has long served as a nexus for London's literary circles, particularly through its proximity to the Bloomsbury Group, a collective of writers and intellectuals whose works profoundly shaped modernist literature. Virginia Woolf, a central figure in the group, evoked the area's intellectual ambiance in her writings, drawing inspiration from the surrounding Georgian elegance and vibrant social networks; for instance, she recalled a prominent hostess in Bedford Square who enriched the literary scene for figures like D.H. Lawrence and T.S. Eliot.[53] The square's location in Bloomsbury facilitated gatherings that influenced novels exploring themes of urban life and creativity, underscoring its role as a backdrop for early 20th-century literary innovation.[54] Artistically, Bedford Square emerged as a hub for the Bloomsbury artists, with No. 44 serving as the residence of Lady Ottoline Morrell, whose salon attracted Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and other group members, fostering collaborations in painting and design that blended aesthetics with social commentary.[39] Today, the Sotheby's Institute of Art, located on the square, continues this legacy by hosting lectures and events on contemporary art, providing students and scholars access to auction house insights and expert discussions that bridge historical and modern artistic practices.[55] In 2025, the nonprofit Yan Du Projects opened at 19 Bedford Square, a Georgian townhouse dedicated to supporting artists of diverse Asian backgrounds through exhibitions and programs that highlight diasporic experiences in contemporary art.[56] The square's intellectual legacy extends to scientific literature, exemplified by Henry Cavendish, who resided at No. 11 and maintained a private library there from the late 18th century, enabling groundbreaking experiments whose documentation advanced fields like chemistry and physics.[57] Similarly, Bedford College, founded in 1849 at No. 47 Bedford Square as the UK's first higher education institution for women, played a pivotal role in feminist writing by empowering female scholars and activists, whose networks contributed to literature on women's rights and education during the suffrage era.[58] Cultural events further enrich this heritage, including the annual Bedford Square Review, organized since the 2010s by Royal Holloway University's creative writing alumni, featuring public readings that celebrate emerging voices in poetry and prose.[59] As a symbol of Georgian elegance, Bedford Square features prominently in art history texts for its cohesive architectural design, representing a pinnacle of 18th-century urban aesthetics that influenced subsequent representations of London in visual and literary works.[10] Its planned layout has also inspired studies in urban planning, serving as a model for balanced green spaces and residential harmony in historical and modern analyses of city development.[43]Recent Developments and Renovations

In 2024, the Bloomsbury London Partnership, comprising the Bedford Estate and other stakeholders, announced a £400 million investment program to revitalize the area over five years, with specific renovations targeting buildings in Bedford Square to create modern office and hotel spaces while adhering to heritage guidelines. This includes sympathetic refurbishments at Nos. 19 and 21 Bedford Square, where period features such as stucco facades and grand staircases have been preserved alongside contemporary updates for commercial use. The project emphasizes sustainability through energy-efficient systems and reduced carbon emissions, aligning with broader goals to enhance Bloomsbury's appeal without compromising its Georgian character.[60][50] Camden Council initiated a public consultation in late 2023, extending into 2024, for public realm improvements around Adeline Place and Bedford Square, aiming to enhance pedestrian safety and reduce vehicle speeds through widened pavements, junction realignments, and traffic calming measures. These changes, part of the Safe and Healthy Streets initiative, seek to foster a more walkable environment while integrating with the square's historic layout. Implementation decisions were approved in 2025, focusing on minimal disruption to the conservation area.[61][62][63] Culturally, Bedford Square saw the temporary installation of the DensiFlora pavilion in November 2024 by the Architectural Association's Emergent Technologies and Design program in collaboration with Populous, showcasing sustainable architecture through rattan-based biomaterial construction on the square's southwest corner. The structure, on view until December 2024, highlighted computational design for eco-friendly public installations. In October 2025, Yan Du Projects opened as a non-profit space at a Georgian townhouse on the square, dedicated to contemporary art by Asian and diasporic artists, beginning with an exhibition of works by Duan Jianyu.[64][65] Sustainability initiatives by the Bedford Estate include green retrofits in square buildings, such as the installation of air source heat pumps and adherence to zero-waste refurbishment protocols using UK-sourced sustainable materials, as seen in recent property upgrades. Energy-efficient windows and modern insulation have been incorporated into renovated structures to lower energy use while maintaining heritage integrity. In the gardens, efforts to boost biodiversity involve low-maintenance planting schemes that support pollinators and wildlife, including participation in Wild Bloomsbury for native reintroduction and beehives in nearby squares to promote local ecosystems, with ongoing enhancements noted since 2023.[66][29] Looking ahead, the Bedford Estate continues to oversee the square's management, prioritizing climate resilience through efficient property maintenance and potential expansions in public access via coordinated street improvements. As of 2025, no significant threats to the square's fabric have emerged, with plans emphasizing adaptive measures for environmental challenges.[67]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography%2C_1912_supplement/Warne%2C_Frederick