Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biomining

View on WikipediaBiomining refers to any process that uses living organisms to extract metals from ores and other solid materials. Typically these processes involve prokaryotes, however fungi and plants (phytoextraction also known as phytomining) may also be used.[1] Biomining is one of several applications within biohydrometallurgy with applications in ore refinement, precious metal recovery, and bioremediation.[2] The largest application currently being used is the treatment of mining waste containing iron, copper, zinc, and gold allowing for salvation of any discarded minerals. It may also be useful in maximizing the yields of increasingly low grade ore deposits.[3] Biomining has been proposed as a relatively environmentally friendly alternative and/or supplementation to traditional mining.[2] Current methods of biomining are modified leach mining processes.[4] These aptly named bioleaching processes most commonly includes the inoculation of extracted rock with bacteria and acidic solution, with the leachate salvaged and processed for the metals of value.[4] Biomining has many applications outside of metal recovery, most notably is bioremediation which has already been used to clean up coastlines after oil spills.[5] There are also many promising future applications, like space biomining, fungal bioleaching and biomining with hybrid biomaterials.[6][7][8]

History of biomining

[edit]The possibility of using microorganisms in biomining applications was realized after the 1951 paper by Kenneth Temple and Arthur Colmer.[9] In the paper the authors presented evidence that the bacteria Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (basonym Thiobacillus ferrooxidans) is an iron oxidizer that thrive in iron, copper and magnesium-rich environments.[9] In the experiment, A. ferrooxidans was inoculated into media containing between 2,000 and 26,000 ppm ferrous iron, finding that the bacteria grew faster and were more motile in the high iron concentrations.[9] The byproducts of the bacterial growth caused the media to turn very acidic, in which the microorganisms still thrived.[10] Following this experiment, the potential to use fungi to leach metals from their environment[11] and use microorganisms to take up radioactive elements like uranium and thorium[12] have also been explored.[11]

While the 1960s was when industrial biomining got its start, humans have been unknowingly using biomining practices for hundreds of years.[13] In western Europe the practice of extracting copper from metallic iron by placing it into drainage streams, used to be considered an act of alchemy.[13] However, today we know that it is a fairly simple chemical reaction.[13]

Cu2+ + Fe0 → Cu0 + Fe2+

In the Middle Ages in Portugal, Spain and Wales, miners unknowingly used this reaction to their advantage when they discovered that when flooding deep mine shafts for a period with some leftover iron they were able to obtain copper.[14]

In China, the use of biomining techniques has been documented as early as 6th-7th century BC.[15] The relationship between water and ore to produce copper was well documented, and during the Tang dynasty and Song dynasty copper was produced using hydrometallurgical techniques.[15] Though the mechanism of oxidation via bacteria was not understood, the unintended use of biomining allowed copper production in China to reach 1000 Tons per year.[15]

Current methods

[edit]Biooxidation (biological pre-treatment)

[edit]Biological pre-treatment utilizes the natural oxidation abilities of microorganisms to remove unwanted minerals that interfere with the extraction of the target metals.[16] This is not always necessary but is widely used in the removal of arsenopyrite and pyrite from gold (Au).[16] Adidithiobacillus spp. release the gold by the following reaction.[17]

- 2 FeAsS[Au] + 7 O2 + 2 H2O + H2SO4 → Fe2(SO4)3 + 2 H3AsO4 + [Au]

Stirred tank bioreactors are used for the biooxidation of gold.[16] While stirred tanks have been used to bioleach cobalt for copper mine tailings,[18] these are costly systems that can reach sizes of >1300m3 meaning that they are almost exclusively used for very high value minerals like gold.[16]

Bioleaching (bioprocessing)

[edit]Dump bioleaching

[edit]Dump Bioleaching was one of the first widely used applications of biomining. In dump bioleaching, waste rock is piled into mounds (>100m tall) and saturated with sulfuric acid to encourage mineral oxidation from native bacteria.[16] Inoculation of the rock with bacteria is often not performed in dump bioleaching which instead relies on the bacteria already present in the rock.[16]

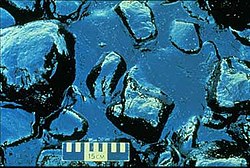

Heap bioleaching

[edit]Heap bioleaching is a newer take on dump leaching.[16] The process includes more processing in which the rocks are ground into a finer grain size.[16] This finer grain is then stacked only 2 – 10 m high and is well irrigated allowing for plenty of oxygen and carbon dioxide to reach the bacteria.[16] The mounds are also often inoculated with bacteria.[16] The liquid coming out at the bottom of the pile, called leachate, is rich in the processed mineral. The heaps reside on large non-porous platforms which are used to catch the leachate for processing.[16] Once collected the leachate is transported to a precipitation plant where the metal is reprecipitated and purified. The waste liquid, now void of the valuable minerals, can be pumped back to the top of the pile and the cycle is repeated.[16]

The temperature inside the leach dump often rises spontaneously as a result of microbial activities.[16] Thus, thermophilic iron-oxidizing chemolithotrophs such as thermophilic Acidithiobacillus species and Leptospirillum and at even higher temperatures the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus (Metallosphaera sedula) may become important in the leaching process above 40 °C.[16]

In situ biomining

[edit]In situ biomining involves the flooding and inoculation of fractured ore bodies that have yet to be removed from the ground.[16] Once the bacteria are introduced to the ore deposits, they begin leaching the precious metals, which can then be extracted as leachate with a recovery well.[19] In-situ mining also shows promise for applications in cost-effective deep subsurface extraction of metals.[20]

In situ biomining, is the one current method utilizing bioleaching that serves as an effective and viable replacement for traditional mining.[21] Because in-situ biomining, negates the need for the extraction of the ore bodies, this method stops the need for any hauling or smelting of the ore.[20] This would mean there would be no waste rocks or mineral tailings that contaminate the surface.[20] However, in-situ biomining also has the most environmental concerns of all of the leaching methods, as there is the potential for the contamination of ground water.[20][21] These concerns however can be careful managed, especially because most of this mining would occur below the water table.[20]

This method was used in Canada in the 1970s to extract additional uranium out of exploited mines.[22] Similarly to copper, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans can oxidize U4+ to U6+ with O2 as electron acceptor. However, it is likely that the uranium leaching process depends more on the chemical oxidation of uranium by Fe3+, with At. ferrooxidans contributing mainly through the reoxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+.

- UO2 + Fe(SO4)3 → UO2SO4 + 2 FeSO4

Applications

[edit]

One of the largest applications of these leaching methods is in the mining of copper Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans has the ability to solubilize copper by oxidizing the reduced form of iron (Fe2+) with sulfur electrons and carbon dioxide.[23] This process results in ferric ions (Fe3+) and H+ in a series of cyclical reactions.

CuFeS2+4H++O2 --> Cu2++Fe2++2S0+2H2O,

4Fe2++4H++O2 4Fe3++2H2O,

2S0+3O2+2H2O→2SO2−4+4H+,

CuFeS2+4Fe3+→Cu2++2S0+5Fe2+,

The copper metal is then recovered by using scrap iron:

- Fe0 + Cu2+ → Cu0 + Fe2+

Using bacteria such as A. ferrooxidans to leach copper from mine tailings has improved recovery rates and reduced operating costs. Moreover, it permits extraction from low grade ores – an important consideration in the face of the depletion of high grade ores.[3]

Economic feasibility and potential drawbacks

[edit]It has been well established that bioleaching allows of the cheaper processing of low-grade ore when the bacteria are given the correct growth conditions.[24] This allows for economic extraction of low-grade ore and increases mining reserves in a sustainable way.[24]

Like any process of mineral recovery there are concerns about the ability to scale biomining to the size the industry would need. The biggest potential drawbacks of biomining are the relatively slow leaching and extraction times and need for expensive specialized equipment.[14] Biomining techniques only show economic viability as a complementary process to mining, not as a replacement. Biomining may make traditional mining more environmentally and economically friendly, by re-processing fresh or abandoned mine tailings and the detoxification of copper production concentrates to generate economically valuable copper-enriched liquors.[24] There is great economic feasibility for in-situ biomining to replace traditional mining in a cheaper and more environmentally friendly way, however it has yet to be adopted on any large scale.[14]

Gold

[edit]Gold is frequently found in nature associated with arsenopyrite and pyrite. In the microbial leaching process Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans etc. dissolve the iron minerals, exposing trapped gold (Au):[25]

- 2 FeAsS[Au] + 7 O2 + 2 H2O + H2SO4 → Fe(SO4)3 + 2 H3AsO4 + [Au]

Biohydrometallurgy is an emerging trend in biomining in which commercial mining plants operate continuously stirred tank reactor (STR) and the airlift reactor (ALR) or pneumatic reactor (PR) of the Pachuca type to extract the low concentration mineral resources efficiently.[3]

The development of industrial mineral processing using microorganisms has been established in South Africa, Brazil and Australia. Iron-and sulfur-oxidizing microorganisms are used to release copper, gold, and uranium from minerals. Electrons are pulled off of sulfur metal through oxidation and then put onto iron, producing reducing equivalents in the cell in the process. This is shown in this figure.[26] These reducing equivalents then go on to produce adenosine triphosphate in the cell through the electron transport chain. Most industrial plants for biooxidation of gold-bearing concentrates have been operated at 40 °C with mixed cultures of mesophilic bacteria of the genera Acidithiobacillus or Leptospirillum ferrooxidans.[27] In other studies the iron-reducing archaea Pyrococcus furiosus were shown to produce hydrogen gas which can then be used as fuel.[28] Using Bacteria such as Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans to leach copper from mine tailings has improved recovery rates and reduced operating costs. Moreover, it permits extraction from low grade ores – an important consideration in the face of the depletion of high grade ores.

The acidophilic archaea Sulfolobus metallicus and Metallosphaera sedula can tolerate up to 4% of copper and have been exploited for mineral biomining. Between 40 and 60% copper extraction was achieved in primary reactors and more than 90% extraction in secondary reactors with overall residence times of about 6 days. All of these microbes are gaining energy by oxidizing these metals. Oxidation means increasing the number of bonds between an atom to oxygen. Microbes will oxidize sulfur. The resulting electrons will reduce iron, releasing energy that can be used by the cell.

Bioremediation

[edit]Bioremediation is the process of using microbial systems to restore the environment to a healthy state by detoxifying and degrading environmental contaminants.[29]

When dealing with mine waste and metal toxic contamination of the environment, bioremediation can be used to lessen the mobility of the metals through the ecosystem.[30] Common mine and metal wastes include arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel and zinc which can make its way into the environment through rain and waterways where it can be moved long distances.[30] These metals pose potential toxicology risks to wild animals and plates as well as humans.[30] When the right microbes are introduced to mines or areas with mining contamination and toxicity, they can alter the structure of the metals to make it less bioavailable and lessening its mobility in the ecosystem.[30] It is important to note however, that certain microbes may increase the amount of metals that get dissolved into the environment.[30] This is why scientific studies and testing must be conducted to find the most beneficial bacteria for the situation.[30]

Bioremediation is not specific to metals. In 1989 an Exxon Valdez oil tanker spilled 42 million liters of crude oil into Prince William Sound.[5] The oil was washed ashore by tides and covered 778 km of the shoreline of the sound, but also spread to covered 1309 km of the gulf of Alaska.[5] In attempts to rejuvenate the coast after the oil spill, Exxon and the EPA began testing bioremediation strategies, which were later implemented on the coast line.[5] They introduced fertilizer to the environment that promoted the growth of naturally occurring hydrocarbon degrading microorganisms.[5] After the applications, microbial assemblages were determined to be made up of 40% oil degrading bacteria, and one year later that number had fallen back to its baseline of around 1%.[5] Two years after the spill, the region of contaminated shoreline spanned 10.2 km.[5] This case indicated that microbial bioremediation may work as a modern technique for restoring natural systems by removing toxins from the environment.

Future prospects

[edit]Additional capabilities, of current bioleaching technologies include the bioleaching of metals from sulfide ores, phosphate ores, and concentrating of metals from solution.[4] One project recently under investigation is the use of biological methods for the reduction of sulfur in coal-cleaning applications.[31]

Biomining in space

[edit]

The concept of space biomining is creating a new field in the world of space exploration.[6] The main space agencies believe that space biomining may provided an approach to the extraction of metals, minerals, nutrients, water, oxygen and volatiles from extraterrestrial regolith.[32][33][6] Bioleaching in space also shows promise for application in building biological life support systems (BLSS).[6] BLSS do not usually contain biological component, however, the use of microorganisms to breakdown waste and regolith, while being able to capture their byproducts like nitrates and methane would theoretically allow for a cyclical system of regenerative life support.[6]

Fungi in biomining

[edit]Species of filamentous fungi, specifically those in the genera of Aspergillus and Penicillium have been shown as effective bioleaching agents.[7] Fungi have the ability to solubilize metals through acidolysis, redoxolysis and chelation reactions.[7] Like bacteria, fungi have been studied for their ability to extract rare earth elements and to process low grade ore. But their most promising and studied usage is in the breakdown of E-waste and the recovery of valuable metals from it, like gold.[7][34] Despite the promise of fungal bioleaching, there has been no industrial applications of it as it does not out compete its bacterial counterparts.[7]

Hybrid biomaterials

[edit]Hybrid Biomaterials are created by attaching peptides to magnetic nanoparticles.[8] The peptides attached are specific proteins that have the capacity to bind to organic/inorganic materials with high affinity.[8] This allows for highly specific custom hybrid molecules to be developed, that bind to molecules of interest.[8] The magnetic nanoparticles that these proteins are bound to, allow for the separation of the biomaterial and the bound molecules from an aqueous solution.[8] There has already been successful development of these hybrid biomaterials for eluting gold and molybdenite from solution, and this technique shows great promise for cleaning up tailing ponds.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ V. Sheoran, A. S. Sheoran & Poonam Poonia (October 2009). "Phytomining: A Review". Minerals Engineering. 22 (12): 1007–1019. Bibcode:2009MiEng..22.1007S. doi:10.1016/j.mineng.2009.04.001.

- ^ a b Jerez, Carlos A (2017). "Biomining of metals: how to access and exploit natural resource sustainably". Microbial Biotechnology. 10 (5): 1191–1194. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.12792. ISSN 1751-7915. PMC 5609284. PMID 28771998.

- ^ a b c Kundu et al. 2014 "Biochemical Engineering Parameters for Hydrometallurgical Processes: Steps towards a Deeper Understanding"

- ^ a b c Johnson, D Barrie (2014). "Biomining—biotechnologies for extracting and recovering metals from ores and waste materials". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 30: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.04.008. PMID 24794631.

- ^ a b c d e f g Atlas, Ronald M.; Hazen, Terry C. (2011-08-15). "Oil Biodegradation and Bioremediation: A Tale of the Two Worst Spills in U.S. History". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (16): 6709–6715. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.6709A. doi:10.1021/es2013227. ISSN 0013-936X. PMC 3155281. PMID 21699212.

- ^ a b c d e Santomartino, Rosa; Zea, Luis; Cockell, Charles S. (2022-01-06). "The smallest space miners: principles of space biomining". Extremophiles. 26 (1): 7. doi:10.1007/s00792-021-01253-w. ISSN 1433-4909. PMC 8739323. PMID 34993644.

- ^ a b c d e Dusengemungu, Leonce; Kasali, George; Gwanama, Cousins; Mubemba, Benjamin (October 2021). "Overview of fungal bioleaching of metals". Environmental Advances. 5 100083. Bibcode:2021EnvAd...500083D. doi:10.1016/j.envadv.2021.100083.

- ^ a b c d e f Cetinel, Sibel; Shen, Wei-Zheng; Aminpour, Maral; Bhomkar, Prasanna; Wang, Feng; Borujeny, Elham Rafie; Sharma, Kumakshi; Nayebi, Niloofar; Montemagno, Carlo (2018-02-20). "Biomining of MoS2 with Peptide-based Smart Biomaterials". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 3374. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21692-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5820330. PMID 29463859.

- ^ a b c Temple, Kenneth L.; Colmer, Arthur R. (1951). "THE AUTOTROPHIC OXIDATION OF IRON BY A NEW BACTERIUM: THIOBACILLUS FERROOXIDANS1". Journal of Bacteriology. 62 (5): 605–611. doi:10.1128/jb.62.5.605-611.1951. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 386175. PMID 14897836.

- ^ Johnson, D Barrie (December 2014). "Biomining—biotechnologies for extracting and recovering metals from ores and waste materials". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 30: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.04.008. PMID 24794631.

- ^ a b Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Qiu, G.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H. (15 November 2013). "A Moderately Thermophilic Mixed Microbial Culture for Bioleaching of Chalcopyrite Concentrate at High Pulp Density". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 80 (2): 741–750. doi:10.1128/AEM.02907-13. PMC 3911102. PMID 24242252.

- ^ Tsezos, Marios (2013-01-01). "Biosorption: A Mechanistic Approach". In Schippers, Axel; Glombitza, Franz; Sand, Wolfgang (eds.). Geobiotechnology I. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Vol. 141. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 173–209. doi:10.1007/10_2013_250. ISBN 978-3-642-54709-6. PMID 24368579.

- ^ a b c Barton, Larry L.; Mandl, Martin; Loy, Alexander, eds. (2010). Geomicrobiology: Molecular and Environmental Perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9204-5. ISBN 978-90-481-9203-8.

- ^ a b c Johnson, D. Barrie (2015). "Biomining goes underground". Nature Geoscience. 8 (3): 165–166. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..165J. doi:10.1038/ngeo2384. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ a b c Qiu, Guanzhou; Liu, Xueduan; Zhang, Ruiyong (2023), Johnson, David Barrie; Bryan, Christopher George; Schlömann, Michael; Roberto, Francisco Figueroa (eds.), "Biomining in China: History and Current Status", Biomining Technologies, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 151–161, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-05382-5_8, ISBN 978-3-031-05381-8, retrieved 2024-03-28

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Johnson, D Barrie (2014). "Biomining—biotechnologies for extracting and recovering metals from ores and waste materials". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 30: 24–31. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2014.04.008.

- ^ Li, Qian; Luo, Jun; Xu, Rui; Yang, Yongbin; Xu, Bin; Jiang, Tao; Yin, Huaqun (2021). "Synergistic enhancement effect of Ag+ and organic ligands on the bioleaching of arsenic-bearing gold concentrate". Hydrometallurgy. 204 105723. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2021.105723.

- ^ Morin, Dominique Henri Roger; d'Hugues, Patrick (2007), Rawlings, Douglas E.; Johnson, D. Barrie (eds.), "Bioleaching of a Cobalt-Containing Pyrite in Stirred Reactors: a Case Study from Laboratory Scale to Industrial Application", Biomining, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 35–55, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-34911-2_2, ISBN 978-3-540-34909-9, retrieved 2024-02-17

- ^ Zhang, Ruiyong; Hedrich, Sabrina; Ostertag-Henning, Christian; Schippers, Axel (June 2018). "Effect of elevated pressure on ferric iron reduction coupled to sulfur oxidation by biomining microorganisms". Hydrometallurgy. 178: 215–223. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2018.05.003.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, D. Barrie (2015). "Biomining goes underground". Nature Geoscience. 8 (3): 165–166. doi:10.1038/ngeo2384. ISSN 1752-0894.

- ^ a b Martínez‐Bellange, Patricio; von Bernath, Diego; Navarro, Claudio A.; Jerez, Carlos A. (January 2022). "Biomining of metals: new challenges for the next 15 years". Microbial Biotechnology. 15 (1): 186–188. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13985. ISSN 1751-7915. PMC 8719796. PMID 34846776.

- ^ McCready, RGL; Gould, WD (1990). "Bioleaching of Uranium". Microbial Mineral Recovery. McGraw-Hill. pp. 107–125.

- ^ Valdés, Jorge; Pedroso, Inti; Quatrini, Raquel; Dodson, Robert J; Tettelin, Herve; Blake, Robert; Eisen, Jonathan A; Holmes, David S (2008). "Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans metabolism: from genome sequence to industrial applications". BMC Genomics. 9 (1): 597. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-597. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 2621215. PMID 19077236.

- ^ a b c Martínez-Bellange, Patricio; von Bernath, Diego; Navarro, Claudio A.; Jerez, Carlos A. (January 2022). "Biomining of metals: new challenges for the next 15 years". Microbial Biotechnology. 15 (1): 186–188. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13985. ISSN 1751-7915. PMC 8719796. PMID 34846776.

- ^ Li, Qian; Luo, Jun; Xu, Rui; Yang, Yongbin; Xu, Bin; Jiang, Tao; Yin, Huaqun (2021). "Synergistic enhancement effect of Ag+ and organic ligands on the bioleaching of arsenic-bearing gold concentrate". Hydrometallurgy. 204 105723. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2021.105723.

- ^ Johnson, D. Barrie; Kanao, Tadayoshi; Hedrich, Sabrina (2012-01-01). "Redox Transformations of Iron at Extremely Low pH: Fundamental and Applied Aspects". Frontiers in Microbiology. 3: 96. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00096. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 3305923. PMID 22438853.

- ^ Qiu, Guanzhou; Li, Qian; Yu, Runlan; Sun, Zhanxue; Liu, Yajie; Chen, Miao; Yin, Huaqun; Zhang, Yage; Liang, Yili; Xu, Lingling; Sun, Limin; Liu, Xueduan (April 2011). "Column bioleaching of uranium embedded in granite porphyry by a mesophilic acidophilic consortium". Bioresource Technology. 102 (7): 4697–4702. Bibcode:2011BiTec.102.4697Q. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.01.038. PMID 21316943.

- ^ Verhaart, Marcel R. A.; Bielen, Abraham A. M.; Oost, John van der; Stams, Alfons J. M.; Kengen, Servé W. M. (2010-07-01). "Hydrogen production by hyperthermophilic and extremely thermophilic bacteria and archaea: mechanisms for reductant disposal". Environmental Technology. 31 (8–9): 993–1003. Bibcode:2010EnvTe..31..993V. doi:10.1080/09593331003710244. ISSN 0959-3330. PMID 20662387. S2CID 40970368.

- ^ Wexler, P (2014). Encyclopedia of Toxicology (3rd ed.). Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Newsome, Laura; Falagán, Carmen (October 2021). "The Microbiology of Metal Mine Waste: Bioremediation Applications and Implications for Planetary Health". GeoHealth. 5 (10) e2020GH000380. Bibcode:2021GHeal...5..380N. doi:10.1029/2020GH000380. ISSN 2471-1403. PMC 8490943. PMID 34632243.

- ^ Xia, Wencheng (2018-01-20). "A novel and effective method for removing organic sulfur from low rank coal". Journal of Cleaner Production. 172: 2708–2710. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.11.141. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Crane, Leah. "Asteroid-munching microbes could mine materials from space rocks". New Scientist. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Cockell, Charles S.; Santomartino, Rosa; Finster, Kai; Waajen, Annemiek C.; Eades, Lorna J.; Moeller, Ralf; Rettberg, Petra; Fuchs, Felix M.; Van Houdt, Rob; Leys, Natalie; Coninx, Ilse; Hatton, Jason; Parmitano, Luca; Krause, Jutta; Koehler, Andrea; Caplin, Nicol; Zuijderduijn, Lobke; Mariani, Alessandro; Pellari, Stefano S.; Carubia, Fabrizio; Luciani, Giacomo; Balsamo, Michele; Zolesi, Valfredo; Nicholson, Natasha; Loudon, Claire-Marie; Doswald-Winkler, Jeannine; Herová, Magdalena; Rattenbacher, Bernd; Wadsworth, Jennifer; Craig Everroad, R.; Demets, René (10 November 2020). "Space station biomining experiment demonstrates rare earth element extraction in microgravity and Mars gravity". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5523. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5523C. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19276-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7656455. PMID 33173035.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

- ^ Bindschedler, Saskia; Vu Bouquet, Thi Quynh Trang; Job, Daniel; Joseph, Edith; Junier, Pilar (2017), "Fungal Biorecovery of Gold From E-waste", Advances in Applied Microbiology, 99, Elsevier: 53–81, doi:10.1016/bs.aambs.2017.02.002, ISBN 978-0-12-812050-7, PMID 28438268

External links

[edit]- "NBIAP News Report." U.S. Department of Agriculture (June 1994).