Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bitmessage

View on Wikipedia| PyBitmessage | |

|---|---|

PyBitmessage version 0.3.5 | |

| Original author | Jonathan Warren |

| Developer | Bitmessage Community |

| Initial release | November 2012 |

| Stable release | 0.6.3.2

/ February 13, 2018 |

| Repository | github |

| Written in | Python, C++ (POW function) |

| Operating system | Windows, macOS, Linux, FreeBSD |

| Available in | English, Esperanto, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Norwegian, Arabic, Chinese |

| Type | Instant messaging client |

| License | MIT |

| Website | bitmessage |

Bitmessage is a decentralized, encrypted, peer-to-peer, trustless communications protocol that can be used by one person to send encrypted messages to another person, or to multiple subscribers.

Bitmessage was conceived by software developer Jonathan Warren, who based its design on the decentralized digital currency, Bitcoin. The software was released in November 2012 under the MIT license.[1]

Bitmessage gained a reputation for being out of reach of warrantless wiretapping conducted by the National Security Agency (NSA), due to the decentralized nature of the protocol, and its encryption being difficult to crack. This prevents the accidental eavesdropping.[2] As a result, downloads of the Bitmessage program increased fivefold during June 2013, after news broke of classified email surveillance activities conducted by the NSA.[1]

It achieves anonymity and privacy by relying on the blockchain flooding propagation mechanism and asymmetric encryption algorithm.[2]

Bitmessage has also been mentioned as an experimental alternative to email by Popular Science[3] and CNET.[4]

Some ransomware programs instruct affected users to use Bitmessage to communicate with the attackers.[5]

PyBitmessage version 0.6.2 (March 1, 2017) had a remote code execution vulnerability. It was fixed in version 0.6.3 (February 13, 2018).[6][7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Max Raskin (2013-06-27). "Bitmessage's NSA-Proof E-Mail". Business Week. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013.

- ^ a b Shi, Liucheng; Guo, Zhaozhong; Xu, Maozhi (2021). "Bitmessage Plus: A Blockchain-Based Communication Protocol With High Practicality". IEEE Access. 9: 21618–21626. Bibcode:2021IEEEA...921618S. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3056135. ISSN 2169-3536. S2CID 231851942.

- ^ Dan Nosowitz (2013-08-09). "What Are Your Options Now For Secure Email?". Popular Science.

- ^ Molly Wood (2013-08-13). "Gmail: You weren't really expecting privacy, were you?". CNet.

- ^ "Chimera Ransomware Tries To Turn Malware Victims Into Cybercriminals". International Business Times. 2015-12-04.

- ^ "CVE - CVE-2018-1000070". cve.mitre.org. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

- ^ "Fix message encoding bug · Bitmessage/PyBitmessage@3a8016d". GitHub. Retrieved 2022-05-09.

Further reading

[edit]- Bitmessage: A Peer-to-Peer Message Authentication and Delivery System (Jonathan Warren) - Bitmessage white paper

External links

[edit]Bitmessage

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins and Initial Development

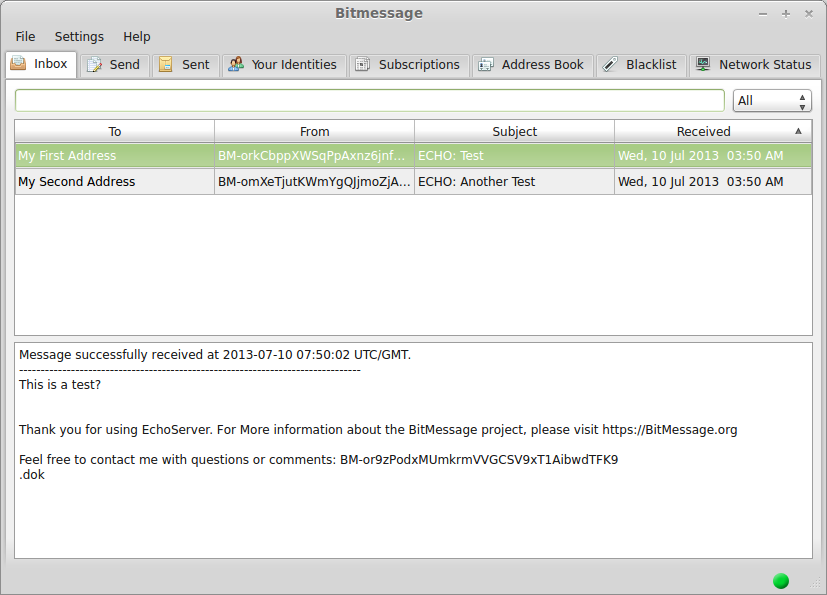

Bitmessage was conceived and initially released by software developer Jonathan Warren in November 2012.[4] The project's foundational document, a whitepaper titled "Bitmessage: A Peer-to-Peer Message Authentication and Delivery System," was published on November 27, 2012, outlining the protocol's design for decentralized messaging.[5] This work drew inspiration from Bitcoin's peer-to-peer architecture to enable trustless communication without reliance on centralized infrastructure.[2] The primary motivation for Bitmessage stemmed from the inherent weaknesses of conventional email systems, including single points of failure at service providers, vulnerability to censorship by authorities or operators, and unavoidable metadata exposure that compromises user privacy.[4] Warren aimed to mitigate these issues by implementing a system where messages are authenticated and delivered via a distributed network, eliminating the need for trusted intermediaries and reducing risks of surveillance or interference.[5] Unlike email's store-and-forward model dependent on servers, Bitmessage emphasized end-to-end anonymity and resilience through flooding messages across peers.[6] The initial implementation, PyBitmessage, served as a proof-of-concept reference client written in Python with a Qt graphical user interface.[1] Released as open-source software under the MIT license, it facilitated early testing and adoption by demonstrating the protocol's feasibility for encrypted, peer-to-peer message exchange.[4] This client adapted Bitcoin-inspired elements, such as network propagation, but focused on messaging rather than financial transactions, prioritizing ease of use over the complexities of public-key infrastructure like PGP.Key Releases and Protocol Evolution

Bitmessage's reference implementation, PyBitmessage, was initially released in November 2012 as version 1.0 by developer Jonathan Warren.[4] This launch coincided with the protocol's debut, but within days, critical cryptographic flaws were exposed, including a defective implementation of padding in encrypted messages that enabled key recovery through attacks akin to Bleichenbacher's oracle exploitation.[7] Early post-launch updates rapidly iterated on the software and protocol to rectify these vulnerabilities and enhance robustness. Version 0.2.0 upgraded elliptic curve cryptography to secp256k1, introduced deterministic address generation, and shortened RIPEMD-160 hashes for addresses to 18 or 19 bytes.[8] By version 0.3.0, protocol version 2 was implemented, adding support for version 3 addresses with signed public keys, nonce trials per byte for proof-of-work variability, and encrypted broadcasts to bolster privacy.[8] Protocol evolution continued with a draft for version 3 released on October 17, 2014, which deprecated certain object types from prior versions, introduced bitfields for optional node features like selective relaying, and emphasized backward compatibility for core message handling; nodes were required to support version 3 objects starting November 16, 2014.[9][10] Software releases incorporated these changes, with version 0.4.0 adding version 4 addresses using encrypted public keys and elevating default proof-of-work difficulty, followed by 0.4.4 explicitly enabling protocol version 3 alongside network rate limiting.[8] Incremental enhancements through the mid-2010s focused on stability and integration, such as version 0.6.0's Qt interface overhaul, TLS support, and mitigations against deanonymization attacks via C/OpenCL-accelerated proof-of-work and UPnP for connectivity.[8] By 0.6.2 in March 2017, updates included Python and OpenSSL upgrades to versions 2.7.12 and 1.0.2h/1.1.0, bootstrap node additions for faster peering, and usability fixes like improved logging and Tor hidden service integration.[8] Emergency patches in 2018's 0.6.3 and 0.6.3.2 addressed remote code execution exploits from 0.6.2, introduced a low-resource network subsystem, and added Dandelion++ for stem-based privacy in message propagation. Development activity tapered, with GitHub commits remaining sporadic into 2024 primarily for maintenance rather than substantive protocol shifts.[1]Community Contributions Post-2012

Following the initial release of Bitmessage in November 2012, maintenance shifted to volunteer-led efforts via the open-source PyBitmessage repository on GitHub, emphasizing decentralized stewardship without a central governing body.[1] Contributors have submitted pull requests addressing infrastructure needs, such as correcting an erroneous link in the UPnP implementation to improve network port mapping compatibility in March 2024. Additional updates have focused on dependency management and code refactoring, including reductions in network module path dependencies in July 2024 and SQL thread optimizations in September 2023, though the pace of such submissions remains low, with only sporadic activity signaling project stagnation.[11] Bootstrap node lists, critical for enabling new instances to connect to the peer-to-peer network, have seen periodic expansions, such as the addition of three nodes in earlier releases to facilitate initial synchronization.[12] Community forks have broadened platform support, exemplified by Pechkin, a lightweight Java client released around 2017 and hosted on SourceForge, which operates on Android, Linux, and Windows to provide mobile-friendly access without relying on the primary Python implementation.[13] These efforts underscore Bitmessage's reliance on distributed, unaffiliated developers for longevity, though the absence of sustained high-volume contributions highlights challenges in sustaining momentum for a niche protocol.[14]Technical Architecture

Core Protocol Mechanics

Bitmessage employs a decentralized peer-to-peer architecture in which nodes connect directly over TCP/IP, utilizing a magic value of 0xE9BEB4D9 to identify valid network payloads and distinguish them from extraneous data.[10] This trustless design eliminates reliance on centralized servers or intermediaries, with nodes autonomously discovering peers through address announcements and maintaining persistent connections for message exchange.[10] Message propagation occurs via a flood-based routing algorithm, where originating nodes broadcast objects to all connected peers, which in turn relay them indiscriminately to their own peers until the message reaches its expiration time or saturates the relevant network stream.[10] This mechanism inherently obscures linkages between senders and receivers by disseminating identical copies across the topology, preventing passive observers from correlating metadata without additional traffic analysis.[15] Core message objects consist of a structured format including an 8-byte nonce, 8-byte expiration timestamp, 4-byte object type, variable-length version and stream number fields, and a variable payload, all contingent on embedded proof-of-work to filter low-effort transmissions prior to flooding.[10] Nodes inventory these objects using hash-based vectors for efficient deduplication and retrieval requests, processing incoming data asynchronously to handle bursts without immediate decryption.[15] Received objects are persisted in local databases, such as SQLite instances for inbox and sent message tables, allowing recipients to perform decryption and validation offline long after propagation concludes.[15] Inventory hashes may be retained post-expiration to avoid redundant reprocessing of duplicates in future floods.[10] Protocol versioning ensures interoperability, with version 3 enforced mandatorily since November 16, 2014, at 22:00:00 GMT, streamlining fields like inventory vectors while preserving backward compatibility for version 2 objects through conditional parsing.[10] Nodes reject connections attempting sub-version-3 handshakes but accommodate mixed-version traffic within streams for gradual adoption.[10]Cryptographic Foundations

Bitmessage employs elliptic curve cryptography based on the secp256k1 curve for key generation, leveraging ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) to produce digital signatures that authenticate message integrity and sender identity.[16][10] Each message includes a signature generated from the sender's private signing key over the message payload, enabling recipients to verify authenticity using the corresponding public verifying key embedded in the address derivation process. This approach ensures that alterations to the message content would invalidate the signature, providing causal protection against tampering without relying on network intermediaries.[4] For confidentiality, Bitmessage uses AES-256 (Advanced Encryption Standard) in CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode with PKCS#7 padding to encrypt message payloads end-to-end.[16][15] The symmetric encryption key and initialization vector derive from a shared secret established via ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman) between the sender's ephemeral encryption keypair and the recipient's static public encryption key, combined with key derivation using double SHA-512 hashing of protocol parameters like address version and stream number.[17][15] An HMAC-SHA-256 (Hash-based Message Authentication Code) authenticates the ciphertext, using a separate key portion from the shared secret to detect modifications or replay attacks. This hybrid asymmetric-symmetric scheme secures payloads against eavesdroppers, as decryption requires the recipient's private encryption key.[16] Addresses in Bitmessage serve as pseudo-anonymous identifiers derived directly from public keys via hashing, specifically applying RIPEMD-160 to a SHA-512 hash of the concatenated public signing and encryption keys, prefixed with version and stream identifiers before Base58Check encoding.[10][18] This process, akin to Bitcoin's address generation but adapted for dual keys, binds the address to the cryptographic material without revealing it explicitly, allowing recipients to validate senders implicitly through signature checks against the derived keys. The hashing chain—SHA-512 followed by RIPEMD-160—produces a compact 160-bit digest resistant to preimage attacks, facilitating lightweight address dissemination while enabling verification of key-address consistency.[4][15] By design, Bitmessage forgoes forward secrecy, relying on static long-term keypairs for all sessions; thus, compromise of a private key exposes all associated past and future messages to decryption, as ephemeral keys are not mandated for each exchange. This trade-off prioritizes simplicity in key management and broadcast compatibility over ephemeral protections, with security hinging on the uncompromised confidentiality of private keys—any breach cascades to full message history due to the deterministic derivation and reuse. Empirical implementations confirm this static model in protocol version 3, where no extension for per-message key rotation exists in core specifications.[10][15]Network Flooding and Routing

Bitmessage employs a flooding-based distribution mechanism for message propagation, wherein objects—such as encrypted messages or public keys—are broadcast to all connected peers within designated streams, a structure defined by stream numbers in object headers that segment the network for targeted dissemination. This ensures comprehensive coverage across participating nodes, obfuscating sender-recipient links by embedding individual communications amid a high volume of traffic, thereby providing plausible deniability as any node could plausibly originate or forward any message.[10][15] Propagation relies on inventory (inv) messages advertising object hashes (computed via double SHA-512), followed by getdata requests for retrieval, with nodes storing received inventory vectors to suppress duplicates and avert redundant flooding.[10] To manage propagation scope and prevent indefinite dissemination, objects include an expiresTime field, capping validity at a maximum of 28 days plus 3 hours from creation, after which nodes discard them but retain inventory records to block reprocessing. Streams enable hierarchical organization, with lower-numbered streams (e.g., Stream 1) serving broader discovery roles while higher streams handle specialized traffic, signaled via protocol headers in version messages that also indicate node capabilities like supported streams. This design forgoes hop-limited TTLs or exponential decay, opting instead for full-network reach within streams to maximize mixing and unlinkability, though it assumes honest majority participation in forwarding.[10][15] Node discovery facilitates initial and ongoing peer connections through address (addr) messages exchanged post-version and verack handshakes, advertising up to 1,000 known peers with addresses retained for approximately 3 hours before expiration. Bootstrapping new nodes depends on a pre-stored list in the knownnodes.dat file containing IP addresses and ports of reliable peers, supplemented by addr exchanges that dynamically expand the peer set upon successful connections.[10][15][19] The inherent trade-off in this flooding paradigm prioritizes anonymity over efficiency, imposing O(n) bandwidth costs per message proportional to network size n, as every node processes and stores incoming objects regardless of relevance. This results in elevated resource demands, particularly storage and transmission overhead, which degrade scalability; for instance, with around 5,000 nodes, full propagation typically completes in under 15 seconds but strains bandwidth as user base grows, prompting proposals like prefix filtering on object nonces to selectively propagate based on stream branches.[15][20][21]Features

Message Types and Addressing

Bitmessage supports private messages directed to specific recipient addresses, broadcast messages intended for subscribers to a designated address, and chan messages for pseudo-channel communications where participants broadcast to a shared address while subscribing anonymously. Private messages are encrypted and routed to a single or multiple target addresses, enabling point-to-point communication without revealing sender-recipient links through metadata. Broadcasts allow senders to disseminate content to all subscribers of an address, with encryption derived from address parameters to ensure only subscribers can decrypt. Chans function similarly to broadcasts but are optimized for ongoing group discussions, where users generate a shared address and subscribe using its public key details, facilitating one-way or interactive feeds without centralized moderation.[9][22] Addresses in Bitmessage are compact Base58Check-encoded strings, typically 33 to 34 characters long, prefixed with "BM-" and encapsulating the address version (such as 3 or 4), stream number (commonly 1 for mainline traffic), and a 20-byte RIPEMD-160 hash of the associated public key. This structure, introduced in the protocol's initial specification on November 27, 2012, supports both ephemeral one-time-use addresses—generated randomly for deniability—and deterministic addresses derived from user-chosen passphrases for reproducibility across devices without key storage dependencies. Unlike traditional email domains, Bitmessage eschews hierarchical naming or registrars, relying instead on hash-based identifiers that bind directly to cryptographic material, reducing reliance on trusted third parties for address validation. Stream numbers partition message flows, with higher streams reserved for experimental or isolated networks to prevent cross-contamination.[23][10] In the reference PyBitmessage client, message handling integrates addressing through dedicated interface elements: the "Your Identities" tab manages an address book stored in keys.dat, listing enabled addresses with options to generate new ones, toggle activity, or delete entries, while the "Subscriptions" tab allows adding broadcast or chan addresses by pasting their string or scanning QR codes for pubkey retrieval. Incoming messages appear threaded in the inbox by subject and timestamp, with filters for unread or labeled items, and outgoing composition in the "Send" tab supports selecting recipients via address autocomplete from the book or manual entry, accommodating multi-recipient privates or broadcasts to chan targets. This UI, refined through community updates post-2012, emphasizes self-custody of keys without server-side persistence.[24][25]Spam Mitigation via Proof-of-Work

Bitmessage implements spam mitigation through a proof-of-work (PoW) requirement imposed on message senders, whereby a nonce is iteratively adjusted in the message payload until repeated applications of the SHA512 hash function yield a result meeting a specified difficulty target—typically defined by a minimum number of leading zero bits in the hash. This computational effort, often taking seconds to minutes on standard hardware depending on the target, creates an economic disincentive for flooding the network with messages, as each transmission demands verifiable work proportional to the difficulty level set by protocol version 3 parameters.[26][9] The PoW difficulty is not uniformly fixed but can be calibrated by receiving nodes, which advertise their acceptance thresholds via thedoingpow network parameter; higher values enforce stricter targets, potentially varying by stream number to address spam prevalence in broader streams like stream 1, where more nodes participate and popular addresses (derived from version 3 or 4 keys) attract higher volumes. Senders must satisfy the minimum network-expected difficulty for propagation, deterring low-cost broadcasts, while verification by nodes involves only a single hash computation, minimizing relay overhead compared to sender costs. This design draws from Hashcash principles, aiming to balance decentralization with spam resistance without relying on centralized blacklists.[10][4]

Empirically, however, the mechanism proves vulnerable to actors with ample resources, such as botnets or specialized hardware, who can parallelize nonce searches to generate messages at scale despite elevated difficulties, as the PoW remains adjustable to the protocol's baseline and lacks adaptive scaling tied directly to address popularity or stream load. Analyses highlight inefficiencies, including wasted computational energy without preventing determined spam campaigns, and note that simple hashing (SHA512 iterations) invites optimization via GPUs or ASICs, undermining the barrier for well-resourced adversaries—contrasting with lighter verification burdens but yielding higher overall network resource demands than targeted email filters. While effective against casual abuse, real-world deployments have observed persistent noise from minimal-effort messages, prompting proposals for hybrid enhancements like prefix filtering or improved nonce schemes.[27][28][29]

Broadcast and Subscription Capabilities

Bitmessage supports broadcast messages as a core primitive for disseminating content to multiple recipients without revealing sender-recipient relationships, achieved through network-wide flooding where all nodes receive and propagate the messages. These broadcasts, classified as type 3 objects in the protocol, are encrypted using keys derived from a double SHA-512 hash of the target address data, enabling decryption only by those possessing the corresponding private key or passphrase.[10] This design obscures metadata, as no direct routing occurs; instead, messages expire after a maximum of 28 days plus 3 hours, preventing indefinite storage.[10] Chan addresses, also known as decentralized mailing lists (DML), facilitate pseudonymous group communication by generating deterministic addresses from a shared passphrase, allowing multiple users to derive the same public-private key pair without a central authority. Users broadcast to the chan address, and messages propagate via the flooding mechanism; subscribers who know the passphrase can decrypt incoming broadcasts matching the address hash during local processing.[30] [4] This enables forum-like anonymity, where participants post under the collective address rather than individual identities, with no inherent moderation or subscriber enumeration possible due to the decentralized key derivation.[31] The subscription model requires clients to add target broadcast addresses to a local list, after which the software filters and decrypts relevant flooded messages for display in the user's inbox, simulating topic-based dissemination without server dependency. For instance, a creator generates a broadcast address—either randomly or passphrase-derived—and shares it externally with intended recipients, who subscribe to poll for and decrypt messages encrypted to that address's hash.[24] [4] This supports applications like decentralized newsletters, where a single broadcaster sends periodic updates to subscribers, hiding participation metadata through the protocol's universal propagation and proof-of-work spam filtering.[32] However, DMLs lack built-in protections against impersonation, as any passphrase holder can forge posts, relying on community norms for integrity.[4]Security and Privacy

Design Intentions for Anonymity

Bitmessage was designed to unlink message senders and receivers by employing a decentralized peer-to-peer flooding mechanism, wherein messages are broadcast network-wide to all connected nodes without routing through specific intermediaries or maintaining central logs. This approach ensures that no single node or authority can correlate traffic patterns to identify originators or destinations, as every node receives and temporarily stores identical copies of messages, which recipients filter and decrypt locally using their private keys. The protocol's creator, Jonathan Warren, intended this to provide metadata resistance by obscuring who is communicating with whom, contrasting with traditional email systems like SMTP that expose sender-receiver pairs via server logs and headers.[23] From first principles, the design breaks potential correlations by treating all nodes as indistinguishable relays, avoiding the circuit-based paths of systems like Tor that could leak timing or volume information if endpoints are compromised. Instead of selective routing, Bitmessage floods messages across streams—segregated subsets of the network for scalability—relying on the assumption of an honest majority of nodes to propagate data without selective censorship or analysis. This causal structure aims to render traffic analysis ineffective for passive observers, as the uniform dissemination mimics broadcast noise, hiding individual communications amid collective volume. Warren emphasized that this enables anonymous publishing and subscription without trusting third parties for delivery.[23] The intentions prioritize protection against IP-metadata linkage over SMTP's traceable envelopes, though the protocol assumes no global adversary controlling over 50% of nodes, which could enable selective flooding or eclipse attacks to isolate targets. By requiring proof-of-work for message injection, it further deters spam while distributing computational load, reinforcing the flooding model's resilience to localized traffic scrutiny. Empirical alignment with these goals positions Bitmessage as superior for sender-receiver unlinkability in non-circuit environments, provided users pair it with external IP obfuscation tools like Tor for endpoint protection.[23][4]Verified Strengths and Empirical Tests

Bitmessage's decentralized peer-to-peer architecture lacks central servers or authorities, enabling operation without kill switches and providing inherent resistance to censorship in environments where network connectivity persists. This design broadcasts all messages network-wide via a flooding mechanism, complicating targeted blocking by adversaries, as confirmed in a 2016 privacy analysis evaluating its non-linkability and untraceability properties.[4] The protocol's trustless nature, relying on hash-based addressing derived from public keys rather than usernames or identifiers, further supports functionality in adversarial settings by minimizing reliance on verifiable external infrastructure.[4] End-to-end encryption employs established primitives including Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme (ECIES) for key encapsulation, AES-256-CBC for symmetric encryption of payloads, and HMAC-SHA-256 for integrity, rendering messages opaque to passive eavesdroppers provided recipients manage private keys securely and avoid reuse across sessions. Analyses up to 2016, including examinations of version 0.4.4 released in October 2014, found no empirical breaches of content confidentiality or basic anonymity under passive observation, attributing security to the protocol's avoidance of metadata leakage like sender-recipient pairs.[4][5] As an open-source protocol with its reference implementation on GitHub since inception, Bitmessage has undergone community-driven code reviews confirming cryptographic integrity following fixes to early vulnerabilities, such as the 2012 transition from custom elliptic curve code to OpenSSL's audited ECC implementation for key generation and signing.[1][7] Post-2012 versions integrate these libraries without reported regressions in core message handling, enabling verifiable audits of proof-of-work nonce generation and message serialization for spam resistance and delivery reliability.[4]Documented Vulnerabilities and Flaws

In the initial version 1.0 released in 2012, Bitmessage employed fundamentally insecure cryptographic primitives, including the reuse of the same RSA keys for both signing and encryption/decryption operations, which facilitated potential attacks, and the direct application of plain RSA without hybrid encryption or proper padding for decrypting broadcast messages via thedecrypt_bigfile() function.[7] This plaintext RSA usage rendered the system vulnerable to malleability attacks, where adversaries could modify ciphertexts predictably to forge messages or potentially recover private keys through chosen-ciphertext manipulations, as textbook RSA lacks semantic security and is susceptible to such exploits without randomization.[7] The protocol transitioned to elliptic curve cryptography using OpenSSL in subsequent versions to mitigate these implementation risks, though the episode underscored the perils of ad-hoc cryptographic design in early decentralized systems.[7]

Bitmessage's core encryption relies on AES-256 in CBC mode with a per-message 128-bit IV derived from a pseudorandom function, but this choice introduces inherent weaknesses, including exposure to side-channel attacks such as cache-timing that could leak keys through processor cache behavior in the underlying OpenSSL implementation.[33] Non-random or reused IVs, if occurring due to poor randomness sources, would further enable dictionary or known-plaintext attacks, amplifying CBC's malleability.[33] While no public padding oracle exploit has been demonstrated—requiring decryption error leaks that the protocol does not explicitly provide—the mode's padding validation process carries theoretical risk of such attacks if future implementations or extensions inadvertently oracle information.[4] These protocol-level selections persist without a core redesign to authenticated modes like GCM, leaving room for causal chains of exploitation in adversarial environments.

A critical implementation flaw emerged in February 2018, where a zero-day remote code execution vulnerability in the PyBitmessage reference client allowed attackers to execute arbitrary code via specially crafted malicious messages targeted at recipients or channel subscribers.[34] The issue arose from insecure message parsing that failed to sanitize inputs, enabling buffer overflows or similar errors that exposed and exfiltrated private keys from integrated Bitcoin wallets, such as Electrum, with active in-the-wild exploitation reported by security researchers.[35] The Bitmessage development team issued an emergency patch on February 14, 2018, urging users to update, change wallet passwords, or migrate funds, but the incident highlighted persistent risks in unhardened P2P clients handling encrypted payloads.[36]

Bitmessage lacks encryption for messages stored at rest on nodes, storing decrypted plaintexts in plain files accessible via local disk inspection, which permits complete compromise of historical communications if an attacker gains node access through malware, physical seizure, or privilege escalation.[4] This absence of at-rest protection—unmitigated in the core protocol—enables straightforward extraction of all retained messages (typically held for two days or longer per node policy), bypassing network-level anonymity for post-compromise forensics.[4] Additionally, the protocol's reliance on ephemeral keys for replies necessitates new broadcasts to recipient addresses, which, combined with the flooding distribution model, can leak metadata about responder activity and communication patterns through observable traffic volumes or timing correlations, without protocol fixes to suppress such signals.[37] These flaws compound in scenarios where nodes must actively transmit to acknowledge or propagate, eroding passive anonymity guarantees.

Implementations

Reference Implementation: PyBitmessage

PyBitmessage serves as the reference implementation of the Bitmessage protocol, developed primarily in Python to provide a cross-platform client for Windows, Linux, and macOS. It features a graphical user interface built with Qt, which integrates core functionalities such as proof-of-work (PoW) computation, peer-to-peer networking, and user interaction for message composition and address management. The client emphasizes decentralized operation without reliance on central servers, handling encryption via integrated cryptographic libraries including OpenSSL for operations like key derivation and message signing.[1][38][8] Architecturally, PyBitmessage focuses on efficient message routing through modules dedicated to network discovery and connectivity, including support for Universal Plug and Play (UPnP) to facilitate port forwarding behind NAT routers. PoW is implemented with a C extension module for accelerated hashing using double SHA-512, essential for spam mitigation by requiring computational effort per outgoing message. OpenSSL integration ensures compatibility with versions up to 1.1.0 and LibreSSL alternatives, supporting secure handling of elliptic curve cryptography for address generation and decryption. The codebase includes subsystems for inventory management, where peers announce and store object hashes to propagate messages across streams without full content transmission initially.[8][39] While the last major release, version 0.6.3.2, occurred in February 2018 to address a remote code execution vulnerability, maintenance continues sporadically through pull requests, such as one in July 2024 reducing dependencies from the network package to streamline builds. Resource demands remain a notable limitation: PoW calculations impose significant CPU usage during message sending, often requiring minutes on standard hardware, while inventory and SQLite-based message storage (in messages.dat) can lead to elevated RAM consumption, particularly in active networks with broadcast-heavy streams, deterring casual users in favor of dedicated operation.[12][15]Alternative Clients and Ports

Pechkin serves as a lightweight alternative client implemented in Java, enabling Bitmessage functionality across Android, Linux, and Windows platforms without reliance on the reference PyBitmessage codebase. Released in alpha versions such as 0.1.1 around October 2017, it emphasizes minimal resource usage for mobile and desktop environments, performing all protocol computations locally without external servers.[13] [40] Recent community tests in 2025 confirmed its cross-platform viability, though it remains in early development with limitations like incomplete feature parity.[14] Minimal routing-focused implementations in Python 3 provide daemon-style alternatives stripped of graphical interfaces, prioritizing network relay and message handling for embedded or headless deployments. For instance, notbit operates as a background service that stores incoming messages and participates in peer-to-peer propagation without user interaction, facilitating lightweight node operations.[41] Similarly, MiNode offers a Python 3-specific reimplementation tailored for protocol compliance in resource-constrained relay scenarios, diverging from the Python 2-based reference to support modern environments.[42] These variants underscore efforts to port core routing logic for interoperability, though they lack full client features like address generation UIs. The Bitmessage protocol's portability has extended to non-benign integrations, as evidenced by 2025 malware samples embedding PyBitmessage library components for command-and-control (C2) over peer-to-peer channels. In May 2025 campaigns, threat actors leveraged the library to cloak C2 directives within standard Bitmessage traffic, bypassing antivirus heuristics via encrypted, decentralized relays.[43] [44] This adaptation highlights the protocol's embeddability in custom payloads, despite originating from the reference implementation, and demonstrates resilience to traffic-based detection in adversarial contexts.[3]Integration with Other Systems

Bitmessage supports integration with external systems primarily through its API and the flexibility of message payloads, allowing developers to build hybrid applications. The PyBitmessage reference client includes a JSON-RPC API that enables custom scripts to perform operations such as generating addresses, sending broadcast or direct messages, and querying message history, which has been used to create bots for automated communication or to interface with other software ecosystems.[45] This API, accessible in daemon mode, permits external applications to treat Bitmessage as a backend for decentralized messaging without requiring a full GUI client.[46] Messages in Bitmessage can contain arbitrary encrypted data, enabling the embedding of cryptocurrency addresses, including Bitcoin addresses, within payloads to facilitate anonymous coordination of transactions or payments outside the protocol's core scope.[47] This capability stems from the protocol's design for trustless, peer-to-peer data exchange, akin to Bitcoin's transaction scripting, though it introduces risks such as deanonymization if addresses are mishandled. In 2018, attackers exploited a remote code execution vulnerability (CVE-2018-1000030) in PyBitmessage by sending malicious messages that executed code to extract Bitcoin private keys from victims' systems, demonstrating how embedded or targeted payloads could bridge to cryptocurrency wallets in adversarial contexts.[34][48] While Bitmessage does not natively federate with email or instant messaging protocols, third-party bridges enable address mapping for interoperability. The Bitmessage Email Gateway, developed by project contributor Peter Surda, provides a bi-directional interface where email addresses are mapped to Bitmessage addresses, allowing outbound emails to be routed via Bitmessage encryption and inbound messages to appear as standard email.[49] Similarly, the Bitmessage Mail Gateway (BMG) integrates with email clients or webmail by converting between protocols, though such bridges require trusted gateways that may compromise the protocol's anonymity guarantees.[38] These implementations remain experimental and are not part of the core protocol, limiting widespread adoption due to compatibility and security trade-offs.[31]Adoption and Challenges

User Base and Network Metrics

Bitmessage saw its highest adoption levels between 2012 and 2014, driven by early enthusiasm for decentralized privacy tools amid growing awareness of surveillance risks.[2] During this period, the protocol attracted interest from cryptocurrency and privacy communities, with node counts reaching several thousand by 2015.[20] By 2025, active participation has dwindled to a niche group of privacy-focused users. The PyBitmessage GitHub repository, serving as the reference implementation, holds 2,863 stars and 573 forks, reflecting modest historical interest but limited recent contributions beyond maintenance updates.[1] Community indicators, such as the r/bitmessage subreddit with 2.8k members and infrequent posts, point to sporadic engagement rather than sustained growth.[50] Network metrics underscore this contraction: message propagation times and peer discovery now rely heavily on static bootstrap lists in files like knownnodes.dat, implying active node counts in the low hundreds rather than thousands.[15] Traffic remains minimal, concentrated on stream 1 for broadcast and private messaging, with higher streams largely unused due to insufficient participant density.[10] Comprehensive public data on daily message volume is scarce, aligning with the protocol's characterization as a low-volume, experimental network in recent analyses.[37]Barriers to Widespread Use

Bitmessage's proof-of-work mechanism, intended to deter spam, demands substantial computational resources, with each message requiring an average of four minutes of CPU-intensive SHA-512 hashing to achieve a partial hash collision.[51] This overhead is exacerbated by the protocol's broadcast model, where messages propagate to all connected nodes, compelling each to store every received message for two days regardless of relevance, leading to elevated bandwidth and storage demands that scale poorly with network growth.[4] In contrast, centralized alternatives like Signal impose negligible resource costs through direct, end-to-end encrypted channels, rendering Bitmessage economically unviable for users prioritizing efficiency over decentralization.[51] User experience hurdles further impede adoption, primarily through the addressing system's reliance on lengthy, hash-derived Base58-encoded strings—typically 32-34 characters long—that resist memorization and manual exchange, unlike phone-number-based or username systems in mainstream apps.[4] The absence of dedicated mobile clients, coupled with the protocol's desktop-centric design and lack of optimization for battery-constrained environments, alienates the majority of users accustomed to seamless, touch-first interfaces.[15] These ergonomic deficiencies create a steep onboarding barrier, as initial setup and ongoing use demand technical familiarity not required by intuitive competitors. Network effects compound these issues via a classic coordination problem: Bitmessage's private messaging utility hinges on reciprocal adoption, yet its persistently small user base—marked by few active peers and no significant growth—renders it impractical for broad communication, as contacts must independently join an underpopulated ecosystem.[15] Unmaintained since 2018, the reference implementation has seen no enhancements to mitigate these dynamics, perpetuating a feedback loop where low participation begets further disuse.[15]Real-World Applications and Misuses

Bitmessage has found niche applications among privacy-focused cryptocurrency communities for anonymous, decentralized messaging, particularly as an alternative to centralized email services in scenarios requiring off-grid or trustless communication.[2][52] Early adopters in these circles, dating back to 2012, valued its peer-to-peer design for evading surveillance in environments where standard internet services might be monitored or unreliable.[2] While intended for censorship-resistant communication, documented use by activists or journalists in censored regions remains limited, with 2010s analyses emphasizing its theoretical suitability over widespread empirical deployment.[4] No evidence of major enterprise adoption exists, as its resource-intensive proof-of-work mechanism and lack of user-friendly interfaces deterred broader integration into professional workflows.[53] In contrast, Bitmessage's anonymity features have been co-opted for illicit purposes, notably in malware operations. In May 2025, a self-spreading worm targeted misconfigured Docker API instances, enlisting them into a Monero-mining botnet while using the PyBitmessage library for covert command-and-control (C2) channels.[54][3] Attackers embedded C2 instructions within legitimate Bitmessage traffic, mimicking normal peer-to-peer exchanges to bypass antivirus heuristics and network monitoring.[44][43] This approach exploited the protocol's flooding mechanism, where messages are broadcast broadly, allowing hidden payloads to blend seamlessly with user-generated data.[55] Similar tactics appeared in backdoor malware deploying coin miners, further demonstrating how the protocol's design enables stealthy, detection-resistant C2 without relying on traditional servers.[3]Impact and Legacy

Influence on Decentralized Communication

Bitmessage's proof-of-work (PoW) mechanism for spam mitigation has informed subsequent peer-to-peer (P2P) messaging designs by demonstrating a decentralized alternative to centralized moderation, requiring senders to expend computational resources proportional to message volume, thereby raising the economic cost of flooding networks.[56] This approach, adapted from Bitcoin's consensus model, influenced protocols aiming to balance anonymity with resistance to denial-of-service attacks, as evidenced in analyses of P2P systems where PoW serves as a primitive for resource-limited environments without trusted intermediaries.[29][15] The protocol's flood-based dissemination, which broadcasts encrypted messages across the network to obscure metadata and sender-recipient links, prefigured similar strategies in later systems prioritizing metadata resistance over efficient routing. For instance, the 2025 EFPIX protocol explicitly draws on Bitmessage's flood routing for its zero-trust encrypted relay, incorporating end-to-end encryption and plausible deniability while addressing key management limitations observed in earlier designs like Bitmessage.[57] EFPIX's framework, which relays messages via probabilistic flooding to evade traffic analysis, credits Bitmessage as a foundational example of metadata-resistant communication, exporting the core idea of network-wide broadcasts to achieve unlinkability in adversarial settings.[58] Bitmessage has contributed to broader discussions on the inherent trade-offs between privacy enhancements and practical usability in decentralized systems, often cited in evaluations of ostensibly "dead" projects whose architectural primitives persist despite scalability flaws. In 2024 Hacker News threads, commentators highlighted Bitmessage's extreme prioritization of privacy—via PoW-enforced delays and broadcast anonymity—as a deliberate dial turned against scalability, yielding enduring lessons for updating primitives in modern P2P messaging amid rising surveillance pressures.[59] These analyses underscore how Bitmessage's uncompromising design, though limiting adoption, modeled causal tensions where stronger anonymity primitives impose bandwidth and latency costs, influencing critiques of usability compromises in successors like blockchain-augmented variants.[15]Criticisms of Scalability Trade-offs

Bitmessage's flooding propagation mechanism, designed to obscure metadata and ensure unlinkability by broadcasting every encrypted message to all nodes, imposes linear communication costs scaling with network size , where represents the number of participants.[60] This "everyone gets everything" approach requires nodes to receive, store, and process all messages—attempting decryption on each to identify recipients—resulting in prohibitive bandwidth and storage demands as the user base expands beyond small scales.[4] For instance, with billions of potential users exchanging dozens of messages daily, the model would overwhelm typical consumer hardware, rendering it infeasible for mass adoption without unproven mitigations like stream segregation or trusted peers, which remain unimplemented.[4] The protocol's proof-of-work (PoW) requirement, intended as spam resistance by mandating computational effort (averaging four minutes per message on standard hardware), exacerbates inefficiencies by wasting resources on both legitimate and malicious traffic without proportional security gains.[4] This mechanism disadvantages users on low-power devices, such as smartphones, due to hardware-dependent hash rates, while failing to deter determined attackers with superior computing resources, as PoW difficulty adjustments do not fully account for advancements in processing capabilities.[27] Empirical critiques highlight that PoW equally burdens senders regardless of intent, contributing to network congestion and reduced practicality, as evidenced by limited real-world throughput even in small deployments.[27] These trade-offs prioritize absolute privacy over usability, positioning Bitmessage as an innovative proof-of-concept rather than a viable production system, with scalability constraints acknowledged by developers and analysts as inherent barriers to broader deployment.[4][60]Current Status as of 2025

As of October 2025, the Bitmessage protocol and its reference implementation, PyBitmessage, exhibit minimal development activity, with the GitHub repository showing only sporadic pull requests such as one reducing path dependencies opened on July 3, 2024, and another correcting a link in the UPnP module opened on March 22, 2024. The last formal release occurred in February 2018, and documentation updates, including the project wiki, remain infrequent, reflecting a lack of sustained maintenance.[12] In May 2025, cybersecurity analyses identified malware campaigns exploiting the PyBitmessage library for encrypted peer-to-peer command-and-control (C2) channels, frequently bundled with Monero cryptocurrency miners to bypass antivirus scanning and network firewalls.[3][44] These incidents, documented by firms including AhnLab's Security Intelligence Center, demonstrate the protocol's enduring effectiveness for covert data exfiltration due to its decentralized broadcast model and lack of central servers, though they also expose vulnerabilities to abuse by threat actors.[43] No substantial revivals, forks, or protocol upgrades have emerged to address longstanding scalability issues, positioning Bitmessage primarily as a niche tool in privacy discussions rather than an active communication standard.[15] Network metrics indicate persistent but low-level operation among a limited set of nodes, with adoption confined to specialized use cases amid broader shifts toward more efficient decentralized alternatives.References

- http://bitcoinwiki.org/wiki/bitmessage