Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

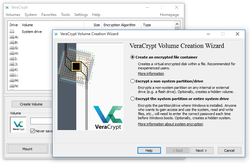

VeraCrypt

View on Wikipedia| VeraCrypt | |

|---|---|

| |

VeraCrypt 1.17 on Windows 10 | |

| Developers | Mounir Idrassi[1] via IDRIX (based in Paris, France)[2] and AM Crypto (based in Kobe, Japan)[3] |

| Initial release | June 22, 2013 |

| Stable release | 1.26.24 (May 30, 2025[4]) [±] |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C, C++, Assembly |

| Operating system |

|

| Platform | IA-32, x86-64, AArch64 and armhf |

| Available in | 43 languages[5] |

| Type | Disk encryption software |

| License | Multi-licensed as Apache License 2.0 and TrueCrypt License 3.0[6] |

| Website | veracrypt |

VeraCrypt is a free and open-source utility for on-the-fly encryption (OTFE).[7] The software can create a virtual encrypted disk that works just like a regular disk but within a file. It can also encrypt a partition[8] or (in Windows) the entire storage device with pre-boot authentication.[9]

VeraCrypt is a fork of the discontinued TrueCrypt project.[10] It was initially released on 22 June 2013. Many security improvements have been implemented and concerns within the TrueCrypt code audits have been addressed. VeraCrypt includes optimizations to the original cryptographic hash functions and ciphers, which boost performance on modern CPUs.

Encryption scheme

[edit]VeraCrypt employs AES, Serpent, Twofish, Camellia, and Kuznyechik as ciphers. Version 1.19 stopped using the Magma cipher in response to a security audit.[11] For additional security, ten different combinations of cascaded algorithms are available:[12]

- AES–Twofish

- AES–Twofish–Serpent

- Camellia–Kuznyechik

- Camellia–Serpent

- Kuznyechik–AES

- Kuznyechik–Serpent–Camellia

- Kuznyechik–Twofish

- Serpent–AES

- Serpent–Twofish–AES

- Twofish–Serpent

The cryptographic hash functions available for use in VeraCrypt are BLAKE2s-256, SHA-256, SHA-512, Streebog and Whirlpool.[13] VeraCrypt used to have support for RIPEMD-160 but it has since been removed in version 1.26.[14]

VeraCrypt's block cipher mode of operation is XTS.[15] It generates the header key and the secondary header key (XTS mode) using PBKDF2 with a 512-bit salt. By default they go through 200,000 or 500,000 iterations, depending on the underlying hash function used and whether it is system or non-system encryption.[16] The user can customize it to lower these numbers to as low as 2,048 and 16,000 respectively.[16]

Security improvements

[edit]- The VeraCrypt development team considered the TrueCrypt storage format too vulnerable to a National Security Agency (NSA) attack, so it created a new format incompatible with that of TrueCrypt. VeraCrypt versions prior to 1.26.5 are capable of opening and converting volumes in the TrueCrypt format.[17][18] Since ver. 1.26.5 TrueCrypt compatibility is dropped.[19]

- An independent security audit of TrueCrypt released 29 September 2015 found TrueCrypt includes two vulnerabilities in the Windows installation driver allowing an attacker arbitrary code execution and privilege escalation via DLL hijacking.[20] This was fixed in VeraCrypt in January 2016.[21]

- While TrueCrypt uses 1,000 iterations of the PBKDF2-RIPEMD-160 algorithm for system partitions, VeraCrypt uses either 200,000 iterations (SHA-256, BLAKE2s-256, Streebog) or 500,000 iterations (SHA-512, Whirlpool) by default (which is customizable by user to be as low as 2,048 and 16,000 respectively).[16] For standard containers and non-system partitions, VeraCrypt uses 500,000 iterations by default regardless of the hashing algorithm chosen (which is customizable by user to be as low as 16,000).[16] While these default settings make VeraCrypt slower at opening encrypted partitions, it also makes password-guessing attacks slower.[22]

- Additionally, since version 1.12, a new feature called "Personal Iterations Multiplier" (PIM) provides a parameter whose value is used to control the number of iterations used by the header key derivation function, thereby making brute-force attacks potentially even more difficult. VeraCrypt out of the box uses a reasonable PIM value to improve security,[23] but users can provide a higher value to enhance security. The primary downside of this feature is that it makes the process of opening encrypted archives even slower.[23][24][25][26]

- A vulnerability in the bootloader was fixed on Windows and various optimizations were made as well. The developers added support for SHA-256 to the system boot encryption option and also fixed a ShellExecute security issue. Linux and macOS users benefit from support for hard drives with sector sizes larger than 512. Linux also received support for the NTFS formatting of volumes.

- Unicode passwords are supported on all operating systems since version 1.17 (except for system encryption on Windows).[17]

- VeraCrypt added the capability to boot system partitions using UEFI in version 1.18a.[17]

- Option to enable/disable support for the TRIM command for both system and non-system drives was added in version 1.22.[17]

- Erasing the system encryption keys from RAM during shutdown/reboot helps mitigate some cold boot attacks, added in version 1.24.[17]

- RAM encryption for keys and passwords on 64-bit systems was added in version 1.24.[17]

VeraCrypt audit

[edit]QuarksLab conducted an audit of version 1.18 on behalf of the Open Source Technology Improvement Fund (OSTIF), which took 32 man-days. The auditor published the results on 17 October 2016.[17][27][28] On the same day, IDRIX released version 1.19, which resolved major vulnerabilities identified in the audit.[29]

Fraunhofer Institute for Secure Information Technology (SIT) conducted another audit in 2020, following a request by Germany's Federal Office for Information Security (BSI), and published the results in October 2020.[30][31]

Security precautions

[edit]There are several kinds of attacks to which all software-based disk encryption is vulnerable. As with TrueCrypt, the VeraCrypt documentation instructs users to follow various security precautions to mitigate these attacks,[32][33] several of which are detailed below.

Encryption keys stored in memory

[edit]

VeraCrypt stores its keys in RAM; on some personal computers DRAM will maintain its contents for several seconds after power is cut (or longer if the temperature is lowered). Even if there is some degradation in the memory contents, various algorithms may be able to recover the keys. This method, known as a cold boot attack (which would apply in particular to a notebook computer obtained while in power-on, suspended, or screen-locked mode), was successfully used to attack a file system protected by TrueCrypt versions 4.3a and 5.0a in 2008.[34] With version 1.24, VeraCrypt added the option of encrypting the in-RAM keys and passwords on x64 editions of Windows, with a CPU overhead of less than 10%, and the option of erasing all encryption keys from memory when a new device is connected.[17]

Tampered hardware

[edit]VeraCrypt documentation states that VeraCrypt is unable to secure data on a computer if an attacker physically accessed it and VeraCrypt is then used on the compromised computer by the user again. This does not affect the common case of a stolen, lost, or confiscated computer.[35] The attacker having physical access to a computer can, for example, install a hardware or a software keylogger, a bus-mastering device capturing memory or install any other malicious hardware or software, allowing the attacker to capture unencrypted data (including encryption keys and passwords) or to decrypt encrypted data using captured passwords or encryption keys. Therefore, physical security is a basic premise of a secure system.[36]

Some kinds of malware are designed to log keystrokes, including typed passwords, that may then be sent to the attacker over the Internet or saved to an unencrypted local drive from which the attacker might be able to read it later, when they gain physical access to the computer.[37]

Trusted Platform Module

[edit]VeraCrypt does not take advantage of Trusted Platform Module (TPM). VeraCrypt FAQ repeats the negative opinion of the original TrueCrypt developers verbatim.[38] The TrueCrypt developers were of the opinion that the exclusive purpose of the TPM is "to protect against attacks that require the attacker to have administrator privileges, or physical access to the computer". The attacker who has physical or administrative access to a computer can circumvent TPM, e.g., by installing a hardware keystroke logger, by resetting TPM, or by capturing memory contents and retrieving TPM-issued keys. The condemning text goes so far as to claim that TPM is entirely redundant.[39]

It is true that after achieving either unrestricted physical access or administrative privileges, it is only a matter of time before other security measures in place are bypassed.[40][41] However, stopping an attacker in possession of administrative privileges has never been one of the goals of TPM. (See Trusted Platform Module § Uses for details.) TPM might, however, reduce the success rate of the cold boot attack described above.[42][43][44][45][46] TPM is also known to be susceptible to SPI attacks.[47]

Plausible deniability

[edit]As with its predecessor TrueCrypt, VeraCrypt supports plausible deniability[48] by allowing a single "hidden volume" to be created within another volume.[49] The Windows versions of VeraCrypt can create and run a hidden encrypted operating system whose existence may be denied.[50] The VeraCrypt documentation lists ways in which the hidden volume deniability features may be compromised (e.g., by third-party software which may leak information through temporary files or via thumbnails) and possible ways to avoid this.[32]

Performance

[edit]VeraCrypt supports parallelized[51]: 63 encryption for multi-core systems. On Microsoft Windows, pipelined read and write operations (a form of asynchronous processing)[51]: 63 to reduce the performance hit of encryption and decryption. On processors supporting the AES-NI instruction set, VeraCrypt supports hardware-accelerated AES to further improve performance.[51]: 64 On 64-bit CPUs VeraCrypt uses optimized assembly implementation of Twofish, Serpent, and Camellia.[17]

License and source model

[edit]VeraCrypt was forked from the since-discontinued TrueCrypt project in 2013,[10] and originally contained mostly TrueCrypt code released under the TrueCrypt License 3.0. In the years since, more and more of VeraCrypt's code has been rewritten and released under the permissive Apache License 2.0.

The TrueCrypt license is generally considered to be source-available but not free and open source. The Apache license is universally considered to be free and open source. The mixed VeraCrypt license is widely but not universally considered to be free and open source.

On 28 May 2014 TrueCrypt ceased development under unusual circumstances,[52][53][54] and there exists no way to contact the former developers.

VeraCrypt is considered to be free and open source by:

- PC World[55]

- Techspot[56]

- DuckDuckGo's Open Source Technology Improvement Fund[57][58]

- SourceForge[59]

- Open Tech Fund[60]

- Fosshub[61]

- opensource.com[62]

- fossmint[63]

VeraCrypt is not considered free and open source by:

- Debian[64] Debian considers all software that does not meet the guidelines of its DFSG to be non-free.

The original TrueCrypt license (but not necessarily the current combined VeraCrypt license) is not considered free and open source by:

- The Free Software Foundation[65][66]

- At least one member of the Open Source Initiative (OSI). The director[67] expressed concern about an older version of the TrueCrypt license, but the OSI itself has not published a determination regarding either TrueCrypt or VeraCrypt.

Legal cases

[edit]In the Canadian court case United States v Burns, the defendant had three hard drives, the first being a system partition which was later found to contain caches of deleted child pornography and manuals for how to use VeraCrypt, with the second being encrypted, and the third having miscellaneous music files. Even though the defendant admitted to having child pornography on his second hard drive, he refused to give the password to the authorities. Despite searching for clues of previously used passwords on the first drive, and inquiries to the FBI about any weaknesses to the VeraCrypt software that could be used to access the drive partition, and brute-forcing the partition with the alphanumeric character set as potential passwords, the partition could not be accessed. Due to the defendant confessing to having child pornography on the encrypted drive, the prosecution applied to force the defendant to give away the password under the foregone conclusion doctrine in the All Writs Act.[68]

In a search of a Californian defendant's apartment for accessing child pornography, a VeraCrypt drive that was over 900 gigabytes was found as an external hard drive. The FBI was called to assist local law enforcement, but the FBI claimed to not have found a weakness in the VeraCrypt software. The FBI also denied having a backdoor within the VeraCrypt software. It was later found that another suspect had educated the defendant into using encryption to hide his photos and videos of child pornography. Because the defendant had admitted to having child pornography on the drive as a backup anyways and chat logs relating to the other suspect educating the defendant on how to use VeraCrypt, the foregone conclusion doctrine was used again.[69]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mounir Idrassi (idrassi)". Archived from the original on 2025-06-02. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ "Contact Us – IDRIX". Archived from the original on 2025-06-04. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ "AM Crypto – Mounir IDRASSI – Cybersecurity & Cryptography Expert". Archived from the original on 2025-06-06. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ "Release Notes". 2025-05-30. Retrieved 2025-06-07.

- ^ "VeraCrypt Files – Source Code". VeraCrypt. English (default) + 42 languages listed in "Translations" folder inside VeraCrypt_1.26.24_Source.zip archive. Retrieved 2025-06-26.

- ^ "root/License.txt". VeraCrypt. TrueCrypt Foundation. 17 Oct 2016. Retrieved 23 Jul 2018.

- ^ "VeraCrypt Official Site"

- ^ "VeraCrypt Volume". VeraCrypt Official Website. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ "Operating Systems Supported for System Encryption". VeraCrypt Official Website. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Rubens, Paul (October 13, 2014). "VeraCrypt a Worthy TrueCrypt Alternative". eSecurity Planet. Quinstreet Enterprise. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Pauli, Darren (October 18, 2016). "Audit sees VeraCrypt kill critical password recovery, cipher flaws". The Register. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018.

- ^ "Encryption Algorithms". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Hash Algorithms". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2024-01-14.

- ^ "Changelog". IDRIX. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ "Modes of Operation". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ a b c d "Header Key Derivation, Salt, and Iteration Count". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "VeraCrypt Release Notes"

- ^ Castle, Alex (March 2015). "Where Are We At With TrueCrypt?". Maximum PC. p. 59.

- ^ "VeraCrypt - Free Open source disk encryption with strong security for the Paranoid". www.veracrypt.fr. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- ^ Constantin, Lucian (September 29, 2015). "Newly found TrueCrypt flaw allows full system compromise". PCWorld. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019.

- ^ CVE-2016-1281: TrueCrypt and VeraCrypt Windows installers allow arbitrary code execution with elevation of privilege

- ^ Rubens, Paul (June 30, 2016). "VeraCrypt a worthy TrueCrypt Alternative". eSecurity Planet. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018.

- ^ a b "PIM". veracrypt.fr. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Khandelwal, Swati (11 August 2015). "Encryption Software VeraCrypt 1.12 Adds New PIM Feature To Boost Password Security". The Hacker News. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Brinkmann, Martin (7 August 2015). "TrueCrypt alternative VeraCrypt 1.12 ships with interesting PIM feature". Ghacks. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "Transcript of Episode #582". GRC.com. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ "The VeraCrypt Audit Results". OSTIF. October 17, 2016. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ QuarksLab (October 17, 2016). VeraCrypt 1.18 Security Assessment (PDF) (Report). OSTIF. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Bédrune, Jean-Baptiste; Videau, Marion (October 17, 2016). "Security Assessment of VeraCrypt: fixes and evolutions from TrueCrypt". QuarksLab. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ "VeraCrypt / Forums / General Discussion: Germany BSI Security Evaluation of VeraCrypt". sourceforge.net. Retrieved 2021-12-01.

- ^ "Security Evaluation of VeraCrypt". Federal Office for Information Security (BSI). 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- ^ a b "Security Requirements and Precautions Pertaining to Hidden Volumes". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Security Requirements and Precautions". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Halderman, J. Alex; et al. (July 2008). Lest We Remember: Cold Boot Attacks on Encryption Keys (PDF). 17th USENIX Security Symposium. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Physical Security". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ Schneier, Bruce (October 23, 2009). ""Evil Maid" Attacks on Encrypted Hard Drives". Schneier on Security. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Malware". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- ^ "FAQ". veracrypt.fr. IDRIX. 2 July 2017.

- ^ "TrueCrypt User Guide" (PDF). truecrypt.org. TrueCrypt Foundation. 7 February 2012. p. 129 – via grc.com.

- ^ Culp, Scott (2000). "Ten Immutable Laws Of Security (Version 2.0)". TechNet Magazine. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015 – via Microsoft TechNet.

- ^ Johansson, Jesper M. (October 2008). "Security Watch Revisiting the 10 Immutable Laws of Security, Part 1". TechNet Magazine. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017 – via Microsoft TechNet.

- ^ "LUKS support for storing keys in TPM NVRAM". github.com. 2013. Archived from the original on September 16, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- ^ Greene, James (2012). "Intel Trusted Execution Technology" (PDF) (white paper). Intel. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 11, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ Autonomic and Trusted Computing: 4th International Conference (Google Books). ATC. 2007. ISBN 9783540735465. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ Pearson, Siani; Balacheff, Boris (2002). Trusted computing platforms: TCPA technology in context. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-009220-5. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ "SetPhysicalPresenceRequest Method of the Win32_Tpm Class". Microsoft. Archived from the original on May 19, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- ^ "TPM Sniffing Attacks Against Non-Bitlocker Targets". secura.com. 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ "Plausible Deniability". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ "Hidden Volume". VeraCrypt Documentation. IDRIX. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ^ a b c "VeraCrypt User Guide" (1.0f ed.). IDRIX. 2015-01-04.

- ^ Buchanan, Bill (May 30, 2014). "Encryption software TrueCrypt closes doors in odd circumstances". The Guardian. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Ratliff, Evan (March 30, 2016). "The Strange Origins of TrueCrypt, ISIS's Favored Encryption Tool". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Buchanan, Bill (Nov 5, 2018). "The Fall of TrueCrypt and Rise of VeraCrypt". medium.com. Medium. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Constantin, Lucian (October 18, 2016). "Critical flaws found in open-source encryption software VeraCrypt". pcworld.com. PC World. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Long, Heinrich (August 3, 2020). "How to Encrypt Files, Folders and Drives on Windows". techspot.com. Techspot. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Hall, Christine (May 4, 2016). "DuckDuckGo Gives $225,000 to Open Source Projects". fossforce.com. FOSS Force. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "A Special Thank You to DuckDuckGo for Supporting OSTIF and VeraCrypt". ostif.org. Open Source Technology Fund. May 3, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Need strong security? VeraCrypt is an open source disk encryption software that gives extra security against brute-force attacks". sourceforge.net. SourceForge. February 8, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ McDevitt, Dan (July 18, 2018). "Privacy and anonymity-enhancing operating system Tails continued the implementation of open-source disk encryption software VeraCrypt into the GNOME user interface". opentech.fund. Open Technology Fund. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "VeraCrypt is a free, open source disk encryption program". fosshub.com. FOSSHub. Jan 17, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Kenlon, Seth (April 12, 2021). "VeraCrypt offers open source file-encryption with cross-platform capabilities". opensource.com. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Afolabi, Jesse (March 5, 2021). "Veracrypt – An Open Source Cross-Platform Disk Encryption Tool". fossmint.com. FOSSMINT. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Debian Bug report logs - #814352: ITP: veracrypt -- Cross-platform on-the-fly encryption". bugs.debian.org. 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Nonfree Software Licenses". gnu.org. Free Software Foundation Licensing and Compliance Lab. January 12, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Various Licenses and Comments about Them". Free Software Foundation. Archived from the original on 2022-12-30.

- ^ Phipps, Simon (2013-11-15), "TrueCrypt or false? Would-be open source project must clean up its act", InfoWorld, archived from the original on 2019-03-22, retrieved 2014-05-20

- ^ US v. Burns, May 10, 2019, retrieved 2023-08-22

- ^ In the Matter of the Search of a Residence in Aptos, California 95003, 2018-03-20, retrieved 2023-08-22

External links

[edit]VeraCrypt

View on GrokipediaHistory

Origins as TrueCrypt Fork

VeraCrypt emerged as a fork of TrueCrypt version 7.1a, the final stable release of the open-source disk encryption software whose anonymous developers announced its discontinuation on May 28, 2014, citing that the code was no longer safe to use and urging migration to Microsoft-proprietary alternatives like BitLocker.[4][5] The TrueCrypt shutdown followed partial results from a crowdfunded security audit initiated in 2013, which identified non-critical issues but no backdoors; full audits completed post-discontinuation confirmed the absence of significant flaws, though the sudden halt fueled speculation about external pressures without conclusive evidence.[6][4] Initiated by Mounir Idrassi, a cryptography expert and founder of the French firm IDRIX, VeraCrypt's development began in 2013 as an effort to enhance TrueCrypt's codebase amid the original project's stagnating updates.[7][8] The fork retained TrueCrypt's core architecture, including its on-the-fly encryption capabilities and support for hidden volumes, while immediately incorporating fixes for audit-identified weaknesses, such as improved random number generation. IDRIX released VeraCrypt 1.0d on June 3, 2014, shortly after the TrueCrypt announcement, positioning it as a secure continuation rather than a mere compatibility layer.[9][10] Unlike contemporaneous forks like CipherShed, which emphasized conservative stability and compatibility, VeraCrypt diverged by prioritizing proactive security hardening, including more robust password-based key derivation to resist brute-force attacks. The project adopted the Apache License 2.0, facilitating easier integration and forking compared to TrueCrypt's restrictive terms, and has since been maintained primarily by Idrassi, with the codebase hosted on SourceForge and GitHub for transparency and community scrutiny.[11][12] By late 2014, features like conversion from TrueCrypt to VeraCrypt volumes were added, solidifying its role as the leading successor amid user distrust of unmaintained legacy software.[13]Development Milestones and Releases

VeraCrypt originated as an open-source fork of TrueCrypt, initiated to address security vulnerabilities and weaknesses identified in preliminary audits of the parent software. Development began under the IDRIX project, with the first public release, version 1.0a, occurring on June 22, 2013. This early version introduced enhancements such as stronger default key derivation iterations and improved resistance to brute-force attacks compared to TrueCrypt 7.1a.[4] Following TrueCrypt's unexpected discontinuation in May 2014, VeraCrypt's maintainers committed to ongoing development, prioritizing the resolution of issues flagged in the comprehensive 2015 Open Crypto Audit Project (OCAP) review of TrueCrypt. By version 1.12 (released February 18, 2015), key fixes included mitigations for backdoor risks, enhanced random number generation, and bootloader security improvements. Subsequent releases through 1.23 (March 30, 2018) focused on cross-platform compatibility, with additions like Linux kernel module signing and macOS APFS support.[14]| Version | Release Date | Key Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| 1.24 | October 6, 2019 | Introduced Personal Iterations Multiplier (PIM) support up to 2,100,000 iterations for customizable key derivation strength; added Jitterentropy RNG for better entropy collection; enabled RAM encryption on Windows to prevent memory dumps; enhanced EFI bootloader with rescue disk recovery.[15] |

| 1.25 | March 2022 (1.25 initial; 1.25.9 in 2023) | Expanded ARM64 architecture support for Windows and macOS; deprecated legacy OS compatibility (e.g., Windows Vista); improved file container handling and added size validation checks.[16] |

| 1.26.7 | October 1, 2023 | Removed legacy TrueCrypt format compatibility to eliminate unmaintained code paths; integrated BLAKE2s as a new pseudo-random function (PRF) option; added support for EMV-compliant banking smart cards as keyfiles for hardware-bound authentication.[17] |

| 1.26.18 | January 20, 2025 | Dropped 32-bit Windows support, setting minimum to Windows 10 version 1809; implemented AES hardware acceleration on ARM64; resolved CVEs including 2024-54187 (denial-of-service) and 2025-23021 (buffer overflow).[15] |

| 1.26.24 | May 30, 2025 | Added Windows screen protection to block screenshots of unlocked volumes; introduced Linux AppImage packaging for portable deployment; updated Whirlpool hash implementation and UI terminology (e.g., "Dismount" to "Unmount").[15] |

| 1.26.27 | September 20, 2025 | Incorporated Argon2id key derivation function; fixed Windows BSOD issues in low-memory scenarios; enhanced CLI options for screen/memory protection and IME enablement; updated Linux dependencies for Ubuntu 25.04 compatibility.[15] |

Technical Foundations

Encryption Algorithms and Modes

VeraCrypt employs symmetric block ciphers for data encryption, supporting both individual algorithms and cascaded combinations, all configured with 256-bit keys and 128-bit block sizes. The available single ciphers include AES (designed by J. Daemen and V. Rijmen), Camellia (developed by Mitsubishi Electric and NTT), Kuznyechik (Russian GOST R 34.12-2015 standard), Serpent (designed by R. Anderson, E. Biham, and L. Knudsen), and Twofish (designed by B. Schneier et al.). VeraCrypt uses AES as the default encryption algorithm, though it does not explicitly recommend a single algorithm over others, as all supported algorithms are considered secure; developers suggest the default settings for most users, providing a balance of security and performance. The default hash algorithm for key derivation is SHA-512. These ciphers are selected during volume creation and cannot be altered afterward, allowing users to prioritize perceived strength or hardware acceleration, such as AES-NI support for AES.[18][19] Access to VeraCrypt volumes using Serpent or other single ciphers is supported across Windows, macOS, Linux, and FreeBSD with the VeraCrypt software installed. However, official support is absent for Android and iOS, where third-party applications such as EDS enable limited access to containers. Mounting on Linux requires root privileges owing to kernel device mapper usage, while macOS often necessitates administrative rights for setup and mounting; restricted environments like work or school systems may preclude access due to these requirements. Although pure AES encryption benefits from native tools in ecosystems such as BitLocker on Windows, VeraCrypt's format mandates its software regardless of cipher, and Serpent introduces no further compatibility constraints beyond lacking such native fallbacks.[20][21] In addition to single ciphers, VeraCrypt supports cascades, where each 128-bit block undergoes sequential encryption by multiple ciphers in XTS mode, each with independent 256-bit keys derived from the master key. The supported cascades are: AES-Twofish; AES-Twofish-Serpent; Camellia-Kuznyechik; Camellia-Serpent; Kuznyechik-AES; Kuznyechik-Serpent-Camellia; Kuznyechik-Twofish; Serpent-AES; Serpent-Twofish-AES; and Twofish-Serpent. Cascades apply the inner cipher first (e.g., in AES-Twofish-Serpent, Serpent encrypts the block, followed by Twofish on the output, then AES), potentially offering resilience if one cipher proves weak, though independent analyses note vulnerability to meet-in-the-middle attacks reducing effective security below the sum of key sizes.[22] All encryption in VeraCrypt utilizes XTS mode for partitions, drives, and virtual volumes, a tweakable codebook mode based on XEX (proposed by Phillip Rogaway in 2003) with ciphertext stealing to handle non-block-aligned data.[23] XTS employs two independent 256-bit keys per cipher: a primary key (K1) for block encryption and a secondary key (K2) for generating the tweak via E_{K2}(data unit sequence number), which is multiplied by a primitive element in GF(2^{128}) and XORed with the plaintext before encryption.[23] The data unit size is fixed at 512 bytes, enabling parallel processing of sectors while providing confidentiality without authentication (users must pair with tools like PIM for integrity if needed).[23] This mode complies with NIST SP 800-38E (2010) and IEEE 1619-2007 standards for storage device protection.[23]Key Derivation and Iteration Mechanisms

VeraCrypt derives encryption keys from user-supplied passwords or keyfiles using two key derivation functions: PBKDF2-HMAC and Argon2id. These functions process the input password combined with a 512-bit random salt to produce a header key, which decrypts the volume header containing the master encryption key. The choice of KDF and its parameters, including iteration counts or memory usage, is selected during volume creation and influences resistance to brute-force attacks by increasing computational cost.[24] PBKDF2-HMAC applies the pseudorandom function (PRF) iteratively, using HMAC variants with underlying hashes such as SHA-512, SHA-256, BLAKE2s-256, Whirlpool, or Streebog. Default iteration counts are 500,000 for non-system volumes, file containers, and system encryption using SHA-512 or Whirlpool, while 200,000 iterations apply to system encryption with other PRFs. Iterations can be adjusted via the Personal Iterations Multiplier (PIM), introduced in VeraCrypt 1.12, using formulas such as 15,000 + (PIM × 1,000) for non-system volumes or SHA-512/Whirlpool system encryption, and PIM × 2048 for other system encryption cases.[25] Higher PIM values extend derivation time, enhancing security against password-cracking hardware like GPUs, though they increase mount or boot durations; minimum PIM thresholds (e.g., 485 for SHA-512 defaults) apply to short passwords to enforce adequate work factors.[25] Argon2id, a memory-hard KDF compliant with RFC 9106, combines data-dependent (Argon2d) and data-independent (Argon2i) modes for resistance to side-channel and GPU-accelerated attacks, employing BLAKE2b internally.[26] Parameters are PIM-controlled: memory cost ranges from 64 MiB to a maximum of 1,024 MiB via min(64 MiB + (PIM - 1) × 32 MiB, 1,024 MiB), with time cost (iterations) calculated as 3 + floor((PIM - 1) / 3) for PIM ≤ 31 or 13 + (PIM - 31) otherwise, and parallelism fixed at 1.[26] Defaults correspond to PIM=12, yielding 416 MiB memory and 6 iterations, prioritizing memory hardness over PBKDF2's CPU-bound iterations for better protection against specialized hardware.[25] Both KDFs support parallelization on multi-core systems during derivation.Core Features

On-the-Fly and Full-Disk Encryption

VeraCrypt employs on-the-fly encryption (OTFE) to provide transparent data protection for encrypted volumes, including file containers, partitions, and system drives. Under OTFE, data written to an encrypted volume is automatically encrypted using the selected algorithms and master keys before storage, while data read from the volume is decrypted in RAM upon access, without requiring manual intervention by the user. This process is managed by a VeraCrypt kernel-mode driver that intercepts input/output operations to the mounted volume, ensuring seamless operation akin to an unencrypted disk once authenticated. For full-disk encryption, VeraCrypt supports system encryption of the boot drive or partition hosting the operating system, primarily Windows, encrypting all data including files, temporary files, hibernation data, pagefiles, logs, and registry entries. The encryption occurs in-place while the OS runs, allowing the process to be paused and resumed, and utilizes the XTS mode of operation with configurable cipher chains such as AES, Serpent, or Twofish. Pre-boot authentication is enforced via the VeraCrypt boot loader, which prompts for the password or key before decrypting the header and loading the OS; in EFI systems, only the system partition is encrypted, whereas MBR mode permits whole-drive encryption. The encryption scheme begins with decrypting the volume header—stored in the first 512 bytes or a backup area—using password-derived keys via PBKDF2 or Argon2id, verifying integrity with a CRC-32 checksum and the "VERA" identifier. Subsequent sector-level read/write operations exclude the header, applying encryption/decryption to data blocks using primary and secondary master keys to support features like hidden volumes. This mechanism ensures that unauthorized access to the physical drive yields only ciphertext indistinguishable from random data. VeraCrypt's OTFE and full-disk capabilities extend to non-system volumes on Windows, macOS, and Linux, though system encryption remains Windows-centric due to boot loader integration requirements. On Linux, VeraCrypt offers an AppImage portable binary for accessing encrypted volumes without prior installation: download and place the AppImage on the drive, make it executable if necessary (e.g., viachmod +x), run it, enter the password, and mount the volume; this supports all ciphers including Serpent and functions on most modern distributions.[27]

Plausible Deniability and Hidden Volumes

VeraCrypt implements plausible deniability through hidden volumes, allowing users to conceal sensitive data within an outer volume containing decoy files, such that an adversary cannot prove the existence of the hidden compartment. This feature relies on steganography: the hidden volume resides in the free space of the outer volume, with its header stored at a random offset appearing as random data when the outer volume is decrypted. Upon mounting with the outer volume's password, only innocuous data is revealed; the hidden volume password decrypts the concealed area without altering the outer volume's apparent randomness. VeraCrypt also supports hidden operating systems for bootable plausibly deniable setups, cloning the system partition into a hidden volume. To create a hidden volume, the Volume Creation Wizard first prompts for an outer volume (standard VeraCrypt volume with decoy files), then allocates space within its data area for the hidden volume, scanning the cluster bitmap to determine feasible sizes (e.g., ensuring at least 65536 bytes for the header). Distinct passwords are required for each, and the process disables options like quick format to avoid detectability. When mounting, VeraCrypt first attempts decryption with the provided password against the standard header; failure triggers a search for the hidden header in RAM-loaded random data blocks. Users can enable "Protect hidden volume" mode, prompting for confirmation to avoid accidental writes to the outer volume. Plausible deniability holds only if security precautions are followed, as undecrypted VeraCrypt volumes resemble random data without identifiable signatures. Key risks include data leaks from operating system writes (e.g., temporary files or filenames) when mounting; mitigation requires using live CDs, read-only outer volume access, or non-journaling filesystems like FAT. Devices with wear-leveling, such as SSDs or flash drives, can retain fragmented traces of hidden data due to uneven block usage, undermining undetectability. Additional practices include regular use of the decoy outer volume to maintain credible activity patterns, avoiding defragmentation or backups that could expose patterns, and using tools like SDelete to securely erase free space. Failure to prevent overwrites risks corrupting the outer volume if hidden space is misallocated.Security Enhancements

Improvements Over TrueCrypt

VeraCrypt enhances the security of TrueCrypt's core cryptographic mechanisms primarily through modifications to the key derivation process, addressing vulnerabilities identified in prior audits, and bolstering resistance to brute-force attacks. The PBKDF2 function in TrueCrypt employed relatively low iteration counts, such as 1,000 for RIPEMD-160 in system encryption scenarios, which proved insufficient against modern hardware-accelerated attacks.[28][29] In contrast, VeraCrypt mandates fixed higher counts—ranging from 327,661 to 655,331 iterations depending on the selected hash algorithm—calibrated to require approximately 0.25 to 0.5 seconds of computation on contemporary hardware, thereby exponentially increasing the time required for exhaustive password searches.[2][14] This adjustment renders VeraCrypt volumes significantly more resilient to GPU- or ASIC-based cracking attempts compared to unpatched TrueCrypt containers.[30] A notable addition is the Personal Iterations Multiplier (PIM) feature, which permits users to independently specify the number of PBKDF2 iterations beyond the default, decoupling derivation strength from password entropy. For non-system volumes, this allows arbitrarily high iterations (e.g., millions) to counter weak passphrases without impacting boot performance; for system encryption, PIM values are limited to maintain usability while still exceeding TrueCrypt's baseline.[31] This flexibility mitigates risks from low-entropy keys, a common failure mode in TrueCrypt deployments where users relied solely on iteration defaults.[32] VeraCrypt also rectifies specific flaws flagged in TrueCrypt's 2014-2015 audits by Quarkslab and the Open Crypto Audit Project, including buffer overflow risks in the boot loader, improper random number generation in certain edge cases, and potential side-channel leaks during key derivation.[31] The EFI boot loader received targeted hardening, such as improved driver handling for disk I/O controls and manual configuration editing to prevent tampering or bypass attempts during pre-boot authentication—issues that left TrueCrypt systems vulnerable to cold-boot or evil-maid attacks.[15] Furthermore, VeraCrypt phased out deprecated or weak components inherited from TrueCrypt, like RIPEMD-160 as a default hash (retained only for compatibility) and certain legacy modes, while introducing support for Argon2id as an optional key derivation function in later versions for enhanced memory-hardness against parallelized attacks.[33] These changes collectively elevate VeraCrypt's posture against both known exploits and evolving threats, without introducing unverified alterations to the underlying cipher implementations.[2]Independent Audits and Vulnerability Resolutions

In August 2016, the Open Source Technology Improvement Fund (OSTIF) funded an independent security audit of VeraCrypt version 1.18 by Quarkslab, a cybersecurity firm, focusing on code review for vulnerabilities in the core application and bootloaders.[34] The assessment, conducted between August 16 and September 14, 2016, uncovered 8 critical vulnerabilities (primarily buffer overflows and improper input validation that could enable code execution or denial-of-service), 3 medium-severity issues (such as weak random number generation in certain configurations), and 15 low-severity flaws (including outdated dependencies like an unpatched zlib library).[35] Quarkslab noted that while VeraCrypt had already implemented several security enhancements over TrueCrypt—such as improved bootloaders resistant to certain attacks—the audit revealed risks from non-Western encryption algorithms and legacy compression libraries that could be exploited for remote code execution or privilege escalation.[36] VeraCrypt developers responded promptly by releasing version 1.19 on October 18, 2016, addressing all identified critical and medium vulnerabilities through code refactoring, removal of the vulnerable GOST 28147-89 cipher implementation, elimination of XZip/XUnzip libraries, and patches to bootloader input handling to prevent overflows.[37] Specific fixes included hardening against heap-based buffer overflows in volume mounting routines and updating cryptographic primitives to mitigate weak entropy sources, with the developers verifying that no exploitation was feasible post-patch under standard usage.[34] This release also incorporated prior resolutions from TrueCrypt's 2015 audit, such as fixing CVE-2015-7358 (a local privilege escalation in the Windows driver) and CVE-2015-7575 (a keystroke logging vulnerability via malformed TrueCrypt headers).[15] Subsequent releases have continued vulnerability remediation based on ongoing code analysis and external reports, including patches for CVE-2019-1010208 (an out-of-bounds write in VeraCryptExpander.exe enabling privilege escalation) in version 1.24-Update 7, and Linux-specific kernel interface flaws fixed in 1.26.18 on January 20, 2025. The German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) evaluated VeraCrypt in 2018, confirming the post-audit improvements and recommending it for secure data protection when used with strong passphrases and verified volumes, though noting persistent risks from user-configured weak setups rather than inherent software flaws.[6] No major independent audits beyond the 2016 Quarkslab review have been publicly funded or reported as of October 2025, but the project's open-source model allows community scrutiny, with developers maintaining transparency via detailed release notes for all fixes.[15]Risk Mitigations and Precautions

Memory and Hardware-Based Threats

VeraCrypt volumes store master encryption keys in RAM during on-the-fly decryption, exposing them to extraction attempts if an adversary gains physical access to the device.[38] Cold boot attacks exploit DRAM data remanence, where keys may persist for seconds to minutes after power-off, allowing recovery by cooling and imaging memory chips.[39] VeraCrypt mitigates this through an optional RAM encryption feature, which encrypts master keys in memory using AES-256 with boot-specific random subkeys derived via PBKDF2, combined with large 2 MB memory pages to disperse key material and complicate forensic reconstruction. This mechanism, disabled by default due to a 20-40% performance overhead on typical hardware, provides protection against cold boot but not against live memory dumps by privileged processes or malware.[40] Additional memory risks arise from operating system features like hibernation and paging, which can serialize RAM contents—including unencrypted keys—to disk. VeraCrypt keys are securely wiped from RAM upon volume dismount, but system hibernation files or pagefiles may capture them beforehand unless disabled. Users must manually configure systems to prevent hibernation (e.g., viapowercfg /hibernate off on Windows) and clear or encrypt pagefiles, as VeraCrypt lacks direct control over these.[38] Memory dump files, generated during crashes or debugging, similarly risk exposing keys; VeraCrypt documentation advises disabling automatic dumps in OS settings. A process memory protection mechanism further restricts non-administrator access to VeraCrypt's memory space, reducing risks from unprivileged malware.

Hardware-based threats include tampered components, such as firmware modifications (e.g., BIOS/UEFI rootkits) or physical implants like keyloggers, which bypass software protections if executed before VeraCrypt loads.[38] VeraCrypt offers no inherent defenses against such attacks, as it operates at the software level and assumes trusted hardware; pre-boot access by adversaries can compromise keys during passphrase entry or boot process. Side-channel vulnerabilities, like timing or power analysis on encryption operations, have been scrutinized in audits; the 2016 OSTIF audit identified bootloader flaws potentially exploitable via hardware probes but confirmed fixes in subsequent releases, with no ongoing critical hardware-specific issues reported. Independent evaluations, including the 2018 BSI analysis, verified secure key handling in memory but emphasized that physical device seizure enables key extraction if volumes are mounted.[2] Effective precautions involve strict physical security, boot integrity checks (e.g., Secure Boot), and avoiding untrusted hardware environments.[38]