Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

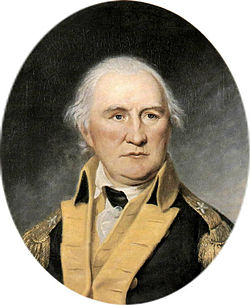

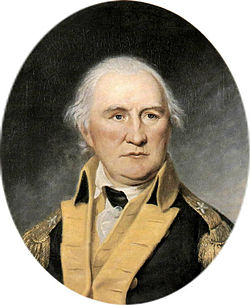

Daniel Morgan

View on Wikipedia

Daniel Morgan (July 6, 1736 – July 6, 1802) was an American pioneer, soldier, and politician from Virginia. One of the most respected battlefield tacticians of the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783, he later commanded troops during the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791–1794.

Key Information

Born in New Jersey to James and Eleanor Morgan, a Welsh family, Morgan settled in Winchester, Virginia. He became an officer of the Virginia militia and recruited a company of riflemen at the start of the Revolutionary War. Early in the war, Morgan served in Benedict Arnold's expedition to Quebec and in the Saratoga campaign. He also served in the Philadelphia campaign before resigning from the army in 1779.

Morgan returned to the army after the Battle of Camden, and led the Continental Army to victory in the Battle of Cowpens. After the war, Morgan retired from the army again and developed a large estate. He was recalled to duty in 1794 to help suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, and commanded a portion of the army that remained in Western Pennsylvania after the rebellion. A member of the Federalist Party, Morgan twice ran for the United States House of Representatives, winning election to the House in 1796. He retired from Congress in 1799 and died in 1802.

Early years

[edit]Daniel Morgan is believed to have been born in the community of New Hampton in Lebanon Township, New Jersey.[2][3] All four of his grandparents were Welsh immigrants who lived in Pennsylvania.[4] Morgan's parents were born in Pennsylvania and then later moved to New Jersey together. Morgan was the fifth of seven children of James Morgan (1702–1782) and Eleanor Lloyd (1706–1748). When Morgan was 17, he left home following a fight with his father. After working at odd jobs in Pennsylvania, he moved to the Shenandoah Valley. He finally settled on the Virginia frontier, near what is now Winchester, Virginia.[5]

He worked clearing land, running a sawmill, and as a teamster.[5] In a little more than two years, he saved enough to buy his own team.[6] With multiple extra wagons, this operation quickly expanded into a thriving business.[5] Morgan served as a civilian teamster during the French and Indian War[5][6][7] with Daniel Boone, sometimes said to be his cousin.[8][9] During the retreat from Fort Duquesne (Pittsburgh), he was punished with 500 lashes (a usually fatal sentence) for attacking an officer.[5][7] Morgan thus acquired a disdain for British authorities and their treatment of provincials.[5] Later, when he led troops, he banned flogging.[5]

He continued as a wagoner, which much of the profits initially being spent on alcohol, gambling, and female company, and resulted in several appearances before a Virginia magistrate, for charges from assault, through the burning down of a neighbours tobacco shed, to horse theft. Though he earned enough to purchase a house, between Winchester and Battletown, with 225 acres of land, and ten slaves, by 1774.[10][11] He would meet Abigail Curry, who would teach him to read and write, and by who he would have two daughters, Nancy and Betsy, and later marry.[5]

Morgan later served as a rifleman in the provincial forces assigned to protect the western settlements from French-backed Indian raids. He led a force that relieved Fort Edwards during its siege and successfully directed the defence afterward.[5][6] He served in Dunmore's War, taking part in raids on Shawnee villages in the Ohio Country.

American Revolution

[edit]After the American Revolutionary War began at the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the Continental Congress created the Continental Army in June 1775.[5][7] They called for the formation of 10 rifle companies[6][7] from the middle colonies to support the Siege of Boston,[5] and late in June 1775, Virginia agreed to send two.[7] Morgan was chosen by a unanimous vote by the Committee of Frederick County to form one of these companies and become its commander.[6]

Morgan recruited 96 men[5][6][7] in 10 days[6] and assembled them at Winchester on July 14. This was even larger than authorized strength.[5] His company of marksmen was nicknamed "Morgan's Riflemen". Another company was raised from Shepherdstown by his rival, Hugh Stephenson. Stephenson's company initially planned to meet Morgan's company in Winchester but found them gone. Morgan marched his men 600 miles (970 km) to Boston, Massachusetts in 21 days, arriving on August 6, 1775.[12][13] Locals called it the "Bee-Line March", noting that Stephenson somehow marched his men 600 miles from their meeting point at Morgan's Spring, in 24 days, so they arrived at Cambridge on Friday, August 11, 1775.[14][15] The long rifles used were more accurate and had a longer range than other firearms at that time – 300 yards (270 m) as compared to 80 yards (73 m) for standard smooth-bore muskets – but took much longer to load.[5] As they were handmade, calibres varied, requiring differently sized bullets.[5] When his men were done training Morgan used them as snipers, shooting mostly British officers who thought they were out of range; sometimes they killed 10 British in a day.[5] This caused great outrage within and without the British army; amongst others, Washington disapproved of this way of war, and when gunpowder began to run out he forbade Morgan to fight in such a manner.[5]

Invasion of Canada

[edit]In June that year, the Continental Congress authorized an invasion of Canada.[16] Colonel Benedict Arnold convinced General Washington to start an eastern offensive in support of Montgomery's invasion. Washington agreed to dispatch three companies from his forces at Boston, provided they agreed. Every company at Boston volunteered, and a lottery was used to choose who should go. Morgan's company was one of them. Benedict Arnold selected Captain Morgan to lead the three companies as a battalion. Arnold's expedition set out from Fort Western on September 25, with Morgan leading the advance party.[17]

The Arnold Expedition[18] started with about 1,050 men; by the time they reached Quebec on November 9, that had been reduced to 675.[19] When Montgomery's men arrived, they launched a joint assault. The Battle of Quebec began in a blizzard on the morning of December 31. The Patriots attacked in two pincers, commanded by Montgomery and Arnold.

Arnold attacked against the lower city from the north, but he suffered a leg wound early in the battle. Morgan took command of the force, and he successfully overcame the first rampart and entered the city. Montgomery's force initiated their attack as the blizzard became severe, and Montgomery and many of his troops, except for Aaron Burr, were killed or wounded in the first British volley. With Montgomery down, his attack faltered. British General Carleton consequently was able to lead hundreds of the Quebec militia in the encirclement of the second attack. Carleton was also able to move his cannons and men to the first barricade, behind Morgan's force. Divided and subject to fire from all sides, Morgan's troops gradually surrendered. Morgan handed his sword to a French-Canadian priest, refusing to give it to Carleton in formal surrender. Morgan thus became one of the 372 men captured, and he remained a prisoner of war until he was exchanged in January 1777.

11th Virginia Regiment and Morgan's Riflemen

[edit]When he rejoined Washington early in 1777, Morgan was surprised to learn he had been promoted to colonel for his bravery at Quebec. He was ordered to raise and command a new infantry regiment, the 11th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Line.

On June 13, 1777, Washington also gave Morgan command of the Provisional Rifle Corps, a light infantry force of 500 riflemen chosen from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia regiments of the Continental Army. Morgan simultaneously led the 11th Virginia Regiment, his permanent unit, and this provisional unit.

Washington wrote the following letter to Morgan on August 16, 1777: "Sir: After you receive this, you will march, as soon as possible, with the corps under your command, to Peekskill, taking with you all the baggage belonging to it. When you arrive there, you will take directions from General Putnam, who, I expect, will have vessels provided to carry you to Albany. The approach of the enemy in that quarter has made a further reinforcement necessary, and I know of no corps so likely to check their progress, in proportion to its number, as that under your command. I have great dependence on you, your officers and men, and I am persuaded you will do honor to yourselves, and essential service to your country..... I am, sir, your most obedient servant George Washington."

Many were from his own 11th Regiment, including his friend Captain Gabriel Long, and Long's best snipers, including Corporals John Gassaway, Duncan MacDonald and Private Peter Carland. After their victory at Saratoga, Washington sent them to harass General William Howe's rearguard, and Morgan did so during their entire withdrawal across New Jersey.

Saratoga

[edit]

Col. Morgan is shown in white, right of center

A detachment of Morgan's regiment, commanded by Morgan, was reassigned to the army's Northern Department and on Aug 30 he joined General Horatio Gates to aid in resisting Burgoyne's offensive. He is prominently depicted in the painting of the Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga by John Trumbull.[20]

Freeman's Farm

[edit]Morgan led his regiment, with the added support of Henry Dearborn's 300-man New Hampshire infantry, as the advance to the main forces. On September 19, at Freeman's Farm, they ran into the advance of General Simon Fraser's wing of Burgoyne's force. Every officer in the British advance party died in the first exchange, and the advance guard retreated.

Morgan's men charged without orders, but the charge fell apart when they ran into the main column led by General Hamilton. Benedict Arnold arrived, and he and Morgan managed to reform the unit. As the British began to form on the fields at Freeman's farm, Morgan's men continued to break these formations with accurate rifle fire from the woods on the far side of the field. They were joined by another seven regiments from Bemis Heights.

For the rest of the afternoon, American fire held the British in check, but repeated American charges were repelled by British bayonets.

Bemis Heights

[edit]

Burgoyne's next offensive resulted in the Battle of Bemis Heights on Oct. 7. Morgan was assigned command of the left (or western) flank of the American position. The British plan was to turn that flank, using an advance by 1,500 men. This brought Morgan's brigade once again up against General Fraser's forces. Daniel Morgan's sharpshooters were ordered to specifically shoot British officers and their Native American Guides. In order to cause maximum confusion and disorder among British Troops.[21]

Passing through the Canadian loyalists, Morgan's Virginia sharpshooters got the British light infantry trapped in a crossfire between themselves and Dearborn's regiment. Although the light infantry broke, General Fraser was trying to rally them, encouraging his men to hold their positions when Benedict Arnold arrived. Arnold spotted him and called to Morgan: "That man on the grey horse is a host unto himself and must be disposed of — direct the attention of some of the sharpshooters amongst your riflemen to him!" Morgan reluctantly ordered Fraser shot by a sniper, and Timothy Murphy obliged him.

With Fraser mortally wounded, the British light infantry fell back into and through the redoubts occupied by Burgoyne's main force. Morgan was one of those who then followed Arnold's lead to turn a counter-attack from the British middle. Burgoyne retired to his starting positions, but about 500 men poorer for the effort. That night, he withdrew to the village of Saratoga, New York (renamed Schuylerville in honor of Philip Schuyler) about eight miles to the northwest.

During the next week, as Burgoyne dug in, Morgan and his men moved to his north. Their ability to cut up any patrols sent in their direction convinced the British that retreat was not possible.

New Jersey and retirement

[edit]After Saratoga, Morgan's unit rejoined Washington's main army, near Philadelphia. Throughout 1778 he hit British columns and supply lines in New Jersey but was not involved in any major battles. He was not involved in the Battle of Monmouth but actively pursued the withdrawing British forces and captured many prisoners and supplies. When the Virginia Line was reorganized on September 14, 1778, Morgan became the colonel of the 7th Virginia Regiment.

Throughout this period, Morgan became increasingly dissatisfied with the army and the Congress. He had never been politically active or cultivated a relationship with the Congress. As a result, he was repeatedly passed over for promotion to brigadier, favor going to men with less combat experience but better political connections. While still a colonel with Washington, he had temporarily commanded Weedon's brigade and felt himself ready for the position. Besides this frustration, his legs and back aggravated him from the abuse taken during the Quebec Expedition. He was finally allowed to resign on June 30, 1779, and returned home to Winchester.

Being ordered by General George Washington, in the summer and fall of 1779, Morgan and his riflemen were part of Sullivan's Expedition into the Southern Tier and Finger Lakes regions of New York.

In June 1780, he was urged to re-enter the service by General Gates but declined. Gates was taking command in the Southern Department, and Morgan felt that being outranked by so many militia officers would limit his usefulness. After Gates' disaster at the Battle of Camden, Morgan thrust all other considerations aside, and went to join the Southern command at Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Southern Campaign

[edit]

He met Gates at Hillsborough, and was given command of the light infantry corps on Oct. 2. At last, on October 13, 1780, Morgan received his promotion to brigadier general.

Morgan met his new Department Commander, Nathanael Greene, on December 3, 1780, at Charlotte, North Carolina. Greene did not change his command assignment, but did give him new orders. Greene had decided to split his army and annoy the enemy in order to buy time to rebuild his force. He gave Morgan's command of about 600 men the job of foraging and enemy harassment in the backcountry of South Carolina, while avoiding direct battle.[22]

When this strategy became apparent, the British General Cornwallis sent Colonel Banastre Tarleton's British Legion to track him down. Morgan talked with militia who had fought Tarleton. Morgan decided to disobey orders and provoke a battle.

Battle of Cowpens

[edit]

Morgan chose to make his stand at Cowpens, South Carolina. On the morning of January 17, 1781, they met Tarleton in the Battle of Cowpens. Morgan had been joined by militia forces under Andrew Pickens and William Washington's dragoons. Tarleton's legion was supplemented with the light infantry from several regiments of regulars.

Morgan's plan took advantage of Tarleton's tendency for quick action and his disdain for the militia,[23] as well as the longer range and accuracy of his Virginia riflemen. The marksmen were positioned to the front, followed by the militia, with the regulars at the hilltop. The first two units were to withdraw as soon as they were seriously threatened, but after inflicting damage. This would invite a premature charge from the British.

The tactic resulted in a double envelopment. As the British forces approached, the Americans, with their backs turned to the British, reloaded their muskets. When the British got close to the Americans, the latter turned and fired at point-blank range. In less than an hour, Tarleton's 1,076 men suffered 110 killed and 830 captured; 200 prisoners of war were wounded. The British Legion, among the best units in Cornwallis's army, was effectively destroyed. Archibald McArthur, the captured commander of a battalion of the 71st Regiment of Foot, said after the battle that he "was an officer before Tarleton was born; that the best troops in the service were put under 'that boy' to be sacrificed".[24][25]

Cornwallis had lost not only Tarleton's legion but also his light infantry, losses that limited his speed of reaction for the rest of the campaign. For his actions, Virginia gave Morgan land and an estate that had been abandoned by a Tory. The damp and chill of the campaign had aggravated his sciatica to the point that he was in constant pain; on February 10, he returned to his Virginia farm.[23] In July 1781, Morgan briefly joined Lafayette to pursue Banastre Tarleton once more, this time in Virginia, but they were unsuccessful.[26]

Later life

[edit]

Morgan resigned his commission after serving six-and-a-half years, and at 46 returned home to Frederick County. He was admitted as an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the state of Virginia.[27][28] He turned his attention to investing in land rather than clearing it, and eventually built an estate of more than 250,000 acres (1,000 km2). As part of his settling down in 1782, he joined the Presbyterian Church and, using Hessian prisoners of war, built a new house near Winchester, Virginia. He named the home Saratoga after his victory in New York. The Congress awarded him a gold medal in 1790 to commemorate his victory at Cowpens.[29]

In 1794, he was briefly recalled to national service to help suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, and the same year, he was promoted to major general. Serving under General "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, Morgan led one wing of the militia army into Western Pennsylvania.[30] The massive show of force brought an end to the protests without a shot being fired. After the uprising had been suppressed, Morgan commanded the remnant of the army that remained until 1795 in Pennsylvania, some 1,200 militiamen, one of whom was Meriwether Lewis.[31]

Morgan ran for election to the US House of Representatives twice as a Federalist. He lost in 1794, but won in 1796 with 70% of the vote by defeating Democratic-Republican Robert Rutherford. Morgan served a single term from 1797 to 1799.

He died on his birthday at his daughter's home in Winchester on July 6, 1802. He was buried in Old Stone Presbyterian Church graveyard. The body was moved to the Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, after the American Civil War. His wife, Abigail, died in 1816 and was buried in Logan County, Kentucky.

Legacy

[edit]Daniel Morgan Parkinson, militia officer, official and entrepreneur of frontier Wisconsin, was the son of Morgan's sister Mary, and was named after his famous uncle.[32]

In 1820 Virginia named a new county—Morgan County—in his honor. (It is now in West Virginia.) The states of Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee followed their example. The North Carolina city of Morganton is also named after Morgan, as well as the Kentucky city of Morganfield (originally Morgan's Field) which was founded in 1811 on land which was part of a Revolutionary War land grant to Daniel Morgan. Morgan actually never saw the land, but his daughter's cousin-in-law,[33] Presley O'Bannon, the "Hero of Derna" in the Barbary War, acquired the land, drew up a plan for the town and donated the land for the streets and public square.

In 1881 (on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Cowpens), a statue of Morgan was placed in the central town square of Spartanburg, South Carolina. It is located in Morgan Square and remains in place today.

In late 1951, an attempt was made to reinter Morgan's body in Cowpens, South Carolina, but the Frederick-Winchester Historical Society blocked the move by securing an injunction in circuit court. The event was pictured by a staged photo that appeared in Life magazine.[34]

In 1973, the home Saratoga was declared a National Historic Landmark.

Fort Morgan is a historic masonry pentagonal bastion fort at the mouth of Mobile Bay, Alabama, United States.

Morgan and his actions served as one of the key sources for the fictional character of Benjamin Martin in The Patriot, a motion picture released in 2000.

There is a street named after him in Lebanon Township, Hunterdon County, New Jersey.

A statue of Morgan was erected at the McConnelsville library, in Morgan County, Ohio in 2017.[35]

In Winchester, Virginia, a middle school is named in his honor.[36]

The Daniel Morgan House at Winchester was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.[37]

In the early 1780s, Morgan joined efforts with Col. Nathaniel Burwell to build a water-powered mill in Millwood, Virginia. The Burwell-Morgan Mill is open as a museum and is one of the oldest, most original operational grist mills in the country.

A statue of Morgan is on the west face of the Saratoga Monument in Schuylerville, New York.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ Higginbotham, Don (1979). Daniel Morgan. UNC Press Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8078-1386-7.

- ^ "Major General Daniel Morgan Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org.

- ^ "Lebanon Township, New Jersey Revolutionary War Sites | Lebanon Township Historic Sites". www.revolutionarywarnewjersey.com.

- ^ Edward Morgan Log House Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Genealogy, accessed November 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Swisher, James Kenneth (2019). Daniel Morgan : an inexplicable hero. [Virginia Beach, Virginia]. ISBN 978-1-63393-750-5. OCLC 1083137885.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Graham, James (1859). The life of General Daniel Morgan : of the Virginia line of the Army of the United States, with portions of his correspondence. University of California Libraries. New York : Derby & Jackson.

- ^ a b c d e f Morgan, Richard L. (2001). General Daniel Morgan: Reconsidered Hero. North Carolina Humanities Council. Morganton (N.C.): Burke County Historical Society.

- ^ Wallace, Paul A. W. (2007). Daniel Boone in Pennsylvania. Diane Publishing Inc. ISBN 9781422314975 – via Google Books.

- ^ Robert Morgan says although Boone reportedly claimed Morgan as a cousin, historians have been unable to confirm it.Morgan, Robert (2007). Boone: A Biography. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-56512-455-4.

- ^ Higginbotham pp. 13–15

- ^ "Frontiersman Daniel Morgan". Warfare History Network. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ "e-WV | Bee Line March".

- ^ McCullough, David. 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005) p. 38

- ^ McGraw, Eliza (July 15, 2025). "How a Relentless, 484-Mile March From Virginia to Massachusetts Fueled the Legend of the Dashing Frontier Rifleman". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ "Clio - Welcome". Clio.

- ^ Graham, James (1859). Daniel Morgan : of the Virginia line of the Army of the United States, with portions of his correspondence. p. 56.

- ^ Peckham, Howard H. The War for Independence: A Military History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958) p. 30

- ^ Historians have never reached a consensus on the use of a standard name for this epic journey

- ^ Morgan, Richard (2001). General Daniel Morgan: Reconsidered Hero. p. 13.

- ^ "Key to the Surrender of General Burgoyne". Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ Yost, Russell (February 16, 2012). "Daniel Morgan - The Most Innovative General of the Revolution". The History Junkie. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ^ Golway, Terry. Washington's General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution (New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2005) p. 241

- ^ a b Golway, p. 248

- ^ Golway, pp. 245-248

- ^ Buchanan, John. The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas. John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1997, ISBN 0-471-16402-X, p. 326

- ^ Peckham, p. 167

- ^ "Officers Represented in the Society of the Cincinnati". The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ Metcalf, Bryce (1938). Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783-1938: With the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies Strasburg, VA: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc., p. 229.

- ^ Len Barcousky (March 22, 2009). "Eyewitness 1818: No jail could hold this Pittsburgh thief". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ Higginbotham, pp. 189–91.

- ^ Higginbotham, pp. 193–98.

- ^ Tenney, Horace Addison & David Atwood. Memorial Record of the Fathers of Wisconsin: Containing Sketches of the Lives and Career of the Members of the Constitutional Conventions of 1846 and 1847-8. With a History of Early Settlement in Wisconsin Madison: David Atwood, 1880; pp. 124-25

- ^ Gaffney, Mailing Address: Cowpens National Battlefield 338 New Pleasant Road; Us, SC 29341 Phone:461-2828 Contact. "Daniel Morgan - Cowpens National Battlefield (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Who Will Get the General's Body?: Two Southern Towns Battle Over Grave of Daniel Morgan, Herow of Cowpens." Life, Vol. 31, No. 10 (September 3, 1951), pp. 53–54, 56, and 59.

- ^ "Morgan County unveils new statue". www.whiznews.com. 2017. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- ^ "Daniel Morgan Middle School - Winchester Public Schools". Archived from the original on January 28, 2013.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings" (PDF). Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 2/04/13 through 2/08/13. National Park Service. February 15, 2013. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- ^ "Saratoga National Historical Park". Revolutionary Day. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Babits, Lawrence E. A Devil of a Whipping: The Battle of Cowpens. University of North Carolina Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8078-2434-8.

- Bodie, Idella. The Old Waggoner (Juvenile nonfiction). Sandlapper Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-87844-165-4

- Calahan, North. Daniel Morgan: Ranger of the Revolution. AMS Press, 1961; ISBN 0-404-09017-6

- Graham, James, The Life of General Daniel Morgan of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States: with portions of his correspondence. Zebrowski Historical Publishing, 1859; ISBN 1-880484-06-4

- Higginbotham, Don. Daniel Morgan: Revolutionary Rifleman. University of North Carolina Press, 1961. ISBN 0-8078-1386-9

- Ketcham, Richard M. Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. John Macrae/Holt Paperbacks, 1999. ISBN 9780805061239.

- LaCrosse Jr., Richard B. Revolutionary Rangers: Daniel Morgan's Riflemen and Their Role on the Northern Frontier, 1778–1783. Heritage Books, 2002. ISBN 0-7884-2052-6.

- Zambone, Albert Louis, Daniel Morgan: A Revolutionary Life. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2018.

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Daniel Morgan (id: M000946)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Nomination form for Saratoga to the National Historic Register

- Burwell-Morgan Mill Web site

- "Daniel Morgan Graduate School of National Security". dmgs.org. August 28, 2020. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved December 22, 2024.

- The Society of the Cincinnati

- The American Revolution Institute

Bryce Metcalf, Bryce Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783-1938: With the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies (Strasburg, Va.: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc., 1938), page 108.