Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Caledonia

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2020) |

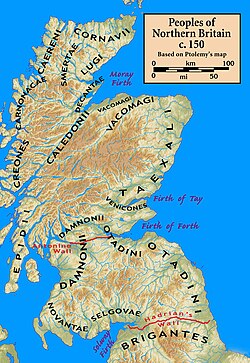

Caledonia (/ˌkælɪˈdoʊniə/; Latin: Calēdonia [kaleːˈdonia]) was the Latin name used by the Roman Empire to refer to the forested region in the central and western Scottish Highlands, particularly stretching through parts of what are now Lochaber, Badenoch, Strathspey, and possibly as far south as Rannoch Moor, known as Coed Celedon (Coed Celyddon using the modern alphabet) to the native Brython (Britons).[1] Today, it is used as a romantic or poetic name for all of Scotland.[2] During the Roman Empire's occupation of Britain, the area they called Caledonia was physically separated from the rest of the island by the Antonine Wall. It remained outside the administration of Roman Britain.

Latin historians, including Tacitus and Cassius Dio, referred to the territory north of the River Forth as "Caledonia", and described it as inhabited by the Maeatae and the Caledonians (Latin: Caledonii).

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]In 1824, Scottish antiquarian George Chalmers posited that Caledonia derived from Cal-ydon, the name of a Greek province famous for its forests. He hypothesized that classical writers such as Tacitus later applied this name to the Scottish Highlands as another area of woods.[3] This derivation is no longer accepted by modern linguists.[4]

According to linguist Stefan Zimmer, Caledonia is derived from the tribal name Caledones (a Latinization of a Brittonic nominative plural n-stem Calēdones or Calīdones, from earlier *Kalē=Black River=don/Danue Goddess[i]oi). He etymologises this name as perhaps 'possessing hard feet' ("alluding to standfastness or endurance"), from the Proto-Celtic roots *kal- 'hard' and *pēd- 'foot', with *pēd- contracting to -ed-. The singular form of the ethnic name is attested as Caledo (a Latinization of the Brittonic nominative singular n-stem *Calidū) on a Romano-British inscription from Colchester. However, some authors have doubted the link between Calidones and kalet- 'hard',[4] especially in light of the theory that the Caledonians and Picts might not have been Celtic speakers.[5]

Toponymy

[edit]The name of the Caledonians may be found in toponymy, such as Dùn Chailleann, the Scottish Gaelic name of the town of Dunkeld, meaning 'fort of the Caledonii', and possibly in that of the mountain Sìdh Chailleann, the 'fairy hill of the Caledonians'.[6][7] According to Historia Brittonum, the site of the seventh battle of the legendary King Arthur was a forest in what is now Scotland, called Coit Celidon in early Welsh.[8][9] The name seems to relate to that of a large central Brythonic tribe, the Caledonii, one amongst several in the area and perhaps the dominant tribe, which would explain the binomial Caledonia/Caledonii.[citation needed]

Modern usage

[edit]

The modern use of "Caledonia" in English and Scots is either as a historical description of northern Britain during the Roman era or as a romantic or poetic name for Scotland as a whole.[9][10]

The name has been widely used by organisations and commercial entities. Notable examples include Glasgow Caledonian University, ferry operator Caledonian MacBrayne, and the now-defunct British Caledonian airline and Caledonian Railway. The Caledonian Sleeper is an overnight train service from London to Scottish destinations.

The Inverness Caledonian Thistle F.C. is a professional football club. In music, "Caledonia" is a popular Scottish patriotic song and folk ballad written by Dougie MacLean in 1977 and published in 1979 on an album of the same name; it has since been covered by various other artists, most notably Frankie Miller and Van Morrison.[11][12] An original rock piece titled Caledonia appeared on Robin Trower's fourth album, "Long Misty Days", where coincidentally Frankie Miller cowrote another track on that album. The web series Caledonia and associated novel is a supernatural police drama that takes place in Glasgow, Scotland.[13][14]

Ptolemy's account in his Geography also referred to the Caledonia Silva, an idea still recalled in the modern expression "Caledonian Forest", although the woods are much reduced in size since Roman times.[15][note 1]

Some scholars point out that the name "Scotland" is ultimately derived from Scotia, a Latin term first used for Ireland (also called Hibernia by the Romans) and later for Scotland, the Scoti peoples having originated in Ireland and resettled in Scotland.[note 2] Another, post-conquest, Roman name for the island of Great Britain was Albion, which is cognate with the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland: Alba.

There is an emerging trend to use the term Caledonia to describe New Caledonia in English, which reflects the usage in French of Calédonie (where the full name is La Nouvelle-Calédonie). The New Caledonian trade and investment department promotes inward investment with the slogan "Choose Caledonia".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The extent of the reduction is a matter of debate. This association with a Silva (literally the flora) reinforces the idea that Caledonia was a forest or forested area named after the Caledonii, or that the people were named after the woods in which they dwelt.

- ^ Bede used a Latin form of the word Scots as the name of the Gaels of Dál Riata. (Bede 1999, p. 386)

References

[edit]- ^ Richmond, Ian Archibald; Millett, Martin J. Millett (2012), "Caledonia", in Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8, retrieved 14 February 2021

- ^ Knowles, Elizabeth (2006), "Caledonia", The Oxford Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198609810.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-860981-0, retrieved 15 February 2021

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Chalmers, George (1824). Caledonia Or, a Historical and Topographical Account of North Britain, from the Most Ancient to the Present Times with a Dictionary of Places Chorographical & Philological - Volume 3. Paisley: Alexander Gardner. p. 4.

- ^ a b Koch 2006, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Mees, Bernard (2023). "Caledonia and the language of the Picts". Scottish Language. 42 (1): 1–15.

- ^ Bennet 1985, p. 26.

- ^ Watson 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Lacy, Ashe & Mancoff 1997, p. 298.

- ^ a b Koch 2006, p. 332.

- ^ Keay & Keay 1994, p. 123.

- ^ "Rock and roll years: the 1970s". The Scotsman. 16 October 2003. Archived from the original on 28 December 2003. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ "Biography". Dougiemaclean.com. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ^ Beacom, Brian (14 January 2014). "New detective drama set to hit our screens". Evening Times. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ "You searched for caledonia". STARBURST Magazine. Retrieved 24 May 2025.

- ^ Smout, MacDonald & Watson 2007, pp. 20–25.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bede (1999) [731]. McClure, Judith; Collins, Roger (eds.). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People; The Greater Chronicle; Bede's Letter to Egbert. World's Classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283866-0.

- Bennet, Donald J., ed. (1985). The Munros. Glasgow: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-13-4.

- Hanson, William S. (2003). "The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes". In Edwards, Kevin J.; Ralston, Ian B. M. (eds.). Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC — AD 1000. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1736-1.

- Haverfield, Francis (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 987.

- Keay, John; Keay, Julia (1994). Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255082-2.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

- Lacy, Norris J.; Ashe, Geoffrey; Mancoff, Debra N. (1997). The Arthurian Handbook (2nd ed.). Garland. ISBN 0-8153-2082-5.

- Moffat, Alistair (2005). Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05133-X.

- Smout, T. C.; MacDonald, Alan R.; Watson, Fiona (2007). A History of the Native Woodlands of Scotland, 1500 — 1920. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3294-7.

- Watson, William J. (2004) [1926]. The Celtic Placenames of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-323-5.

- Zimmer, Stefan (2006) [2004]. "Some Names and Epithets in Culhwch ac Olwen". Studi Celtici. 3: 163–179.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of Caledonia at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Caledonia at Wiktionary- Anglia Scotia et Hibernia – 1628 map of the region by Mercator and Hondius

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. IV (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 662–664.

- Clans of Caledonia – Strategy board game based in historic Scotland