Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Scoti

View on WikipediaScoti or Scotti is a Latin name for the Gaels,[1] first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those who had settled in Great Britain as well; it later came to refer only to Gaels in northern Britain.[1] The kingdom to which their culture spread became known as Scotia or Scotland, and eventually its inhabitants came to be known as Scots.

History

[edit]An early use of the word can be found in the Nomina Provinciarum Omnium (Names of All the Provinces), which dates to about AD 312. This is a short list of the names and provinces of the Roman Empire. At the end of this list is a brief list of tribes deemed to be a growing threat to the Empire, which included the Scoti, as a new term for the Irish.[2] There is also a reference to the word in St Prosper's chronicle of AD 431 where he describes Pope Celestine sending St Palladius to Ireland to preach "ad Scotti in Christum" ("to the Scots who believed in Christ").[3]

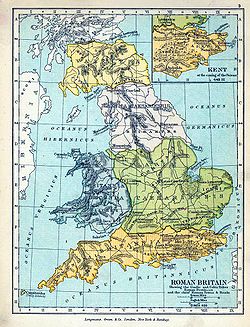

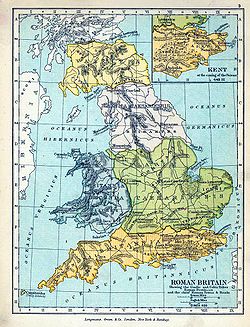

Thereafter, periodic raids by Scoti are reported by several later 4th and early 5th century Latin writers, namely Pacatus,[4] Ammianus Marcellinus,[5] Claudian[6] and the Chronica Gallica of 452.[7] Two references to Scoti have been identified in Greek literature (as Σκόττοι), in the works of Epiphanius, Bishop of Salamis, writing in the 370s.[8] The fragmentary evidence suggests an intensification of Scoti raiding from the early 360s, culminating in the barbarian conspiracy of 367–368, and continuing up to and beyond the end of Roman rule c. 410. The location and frequency of attacks by Scoti remain unclear, as do the origin and identity of the Gaelic population-groups who participated in these raids.[9]

By the 5th century, the Gaelic or Scottish kingdom of Dál Riata had emerged in the area of modern Scotland that is now Argyll. Although this kingdom was destroyed and subjugated by the Pictish kingdom of the 8th century under Angus I, the convergence of Pictish and Gaelic languages over several centuries resulted in the English labelling Pictland under Constantine II as Scottish in the early 10th century, first attested in AD 920, viewing the Picts as speaking a Gaelic tongue. The growing influence of the English and Scots languages from the 12th century with the introduction of Norman-French knights and southerly expansion of Scotland's borders by David I saw the terms Scot, Scottish and Scotland also begin to be used commonly by natives of that country.[10][11]

Etymology

[edit]The etymology of Late Latin Scoti is unclear. It is not a Latin derivation, nor does it correspond to any known Goidelic (Gaelic) term the Gaels used to name themselves as a whole or a constituent population group. Several derivations have been conjectured, but none has gained general acceptance in mainstream scholarship.

In the 19th century, Aonghas MacCoinnich proposed that Scoti came from Gaelic sgaothaich, meaning "crowd" or "horde".[12]

Charles Oman (1910) derived it from Gaelic scuit, meaning someone cut off. He believed it referred to bands of outcast Gaelic raiders, suggesting that the Scots were to the Gaels what the Vikings were to the Norse.[13]

More recently, Philip Freeman (2001) has speculated on the likelihood of a group of raiders adopting a name from an Indo-European root, *skot, citing the parallel in the Ancient Greek skotos (σκότος), meaning "darkness, gloom".[14]

Linguist Kim McCone (2013) derives it from the Old Irish noun scoth meaning "pick", as in "the pick" of the population, the nobility, from an Archaic Irish reconstruction *skotī.[15]

An origin has also been suggested in a word related to the English scot ("tax") and Old Norse skot; this referred to an activity in ceremonies whereby ownership of land was transferred by placing a parcel of earth in the lap of a new owner,[16] whence 11th-century King Olaf, one of Sweden's first known rulers, may have been known as a scot king.[17]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Duffy, Seán. Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge, 2005. p.698

- ^ P. Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, Austin, 2001, pp. 91-92.

- ^ M. De Paor – L. De Paor, Early Christian Ireland, London, 1958, p. 27.

- ^ Pacatus, Panegyric 5.1.

- ^ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae XX 1.1; XXVI 4.5; XXVII 8.5.

- ^ Claudius Claudianus, Panegyricus dictus Honorio Augusto tertium consuli 52–58; Panegyricus dictus Honorio Augusto quartum consuli 24–33; De consulatu Stilichonis II 247–255; Epithalamium dictum Honorio Augusto et Mariae 88–90; Bellum Geticum 416–418.

- ^ Chronica Gallica ad annum 452, Gratiani IV (= T. Mommsen (ed.), Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores antiquissimi IX, Berlin, 1892, p. 646).

- ^ P. Rance, Epiphanius of Salamis and the Scotti: new evidence for late Roman-Irish relations, in Britannia 43 (2012), pp. 227–242.

- ^ P. Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, Austin, 2001, pp. 88-106; P. Rance, Epiphanius of Salamis and the Scotti: new evidence for late Roman-Irish relations, in Britannia 43 (2012), pp. 227–242.

- ^ From Caledonia to Pictland, Scotland to 795, James E. Fraser, 2009, Edinburgh University Press

- ^ From Pictland to Alba, 789-1070, Alex Woolf, 2007, Edinburgh University Press

- ^ A. MacCoinnich, Eachdraidh na h-Alba, Glasgow, 1867, p. 18-19.

- ^ C. Oman, A History of England before the Norman Conquest, London, 1910, p. 157.

- ^ P. Freeman, Ireland and the Classical World, Austin, 2001, pp. 93.

- ^ McCone, Kim (2013). "The Celts: questions of nomenclature and identity", in Ireland and its Contacts. University of Lausanne. p.26

- ^ J. Truedson Demitz, Throne of a Thousand Years: Chronicles as Told by Erik, Son of Riste, Commemorating Sweden's Monarchy from 995–96 to 1995–1996, Ludvika – Los Angeles, 1996, p. 9.

- ^ L.O. Lagerqvist – N. Åberg, Öknamn och tillnamn på nordiska stormän och kungligheter, Stockholm, 1997, p. 23 (etymology of epithets of Nordic kings and magnates).

Bibliography

[edit]- Freeman, Philip (2001), Ireland in the Classical World (University of Texas Press: Austin, Texas. ISBN 978-0-292-72518-8

- Rance, Philip (2012), 'Epiphanius of Salamis and the Scotti: new evidence for late Roman-Irish relations', Britannia 43: 227–242

- Rance, Philip (2015), 'Irish' in Y. Le Bohec et al. (edd.), The Encyclopedia of the Roman Army (Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester/Malden, MA, 2015).

Scoti

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Origins of the Term

The term Scoti (or Scotti) emerged as a Latin descriptor for the Gaelic-speaking peoples of Ireland, with its etymology remaining uncertain and subject to debate among linguists. One prominent theory links it to the Old Irish word scóth, interpreted as "pirate" or "raider," capturing the Roman view of these groups as sea-borne attackers on British shores.[5] This interpretation aligns with classical accounts portraying the Scoti as marauders, though no direct attestation of scóth in that sense survives in early Irish texts. Alternative proposals trace the term to deeper Celtic or Indo-European roots. For instance, it may derive from Proto-Celtic *skot-, connoting "cut off" or "outcast," possibly referring to marginalized or wandering groups, with connections to Old Irish scoith ("to cut off") and scoth ("point" or "edge").[6] Another classical interpretation suggests ties to Indo-European elements meaning "shadow" or "darkness," akin to Greek skotos, potentially evoking the misty, remote origins of the Irish in Roman eyes.[2] The word first appears in Latin sources in the late 3rd to early 4th century CE, such as the Laterculus Veronensis around 314 CE, and later authors like Ammianus Marcellinus, initially denoting Irish inhabitants without implying a broader ethnic or continental identity.[7] Notably, no equivalents exist in pre-Roman Gaelic languages, underscoring the term's exogenous Roman invention rather than an indigenous self-designation.[8] Over time, Scoti extended to Gaelic settlers in what is now Scotland, broadening its application beyond Ireland.Evolution of Usage

The term "Scoti" initially referred exclusively to the Gaelic-speaking inhabitants of Ireland during the Roman era, but between the 5th and 9th centuries CE, its usage began to expand to include Irish settlers in western Scotland, particularly those associated with the kingdom of Dál Riata.[9] Early Irish annals document this shift, recording conflicts and rulers of Dál Riata—such as the death of Aedán son of Mongan, king of Dál Riata, in 616 CE and the victory of Dál Riata at the Battle of Ard Corann in 627 CE—portraying these groups as extensions of Irish Gaelic society establishing a presence in Britain.[10] This evolution reflected the growing political and cultural influence of Gaelic migrants in the region, gradually broadening "Scoti" beyond its Irish origins to denote transmarine Gaelic communities. By the 9th century, in medieval Latin texts, "Scoti" increasingly applied to the Gaelic rulers of the emergent Kingdom of Alba, distinguishing them from the Picts and other indigenous groups. In Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (completed 731 CE), the term initially emphasizes its Irish focus—such as the mission of Palladius to the Christian Scots in Ireland around 431 CE—but evolves to encompass Scottish contexts, including the migration of Scots from Ireland to settle among the Picts under Reuda, forming the Dalreudini in northern Britain, and their subsequent raids alongside Picts on southern territories.[9] This semantic expansion underscored the unification of Gaelic elites in Alba, where "Scoti" came to signify the dominant cultural and ruling class by the time of Kenneth MacAlpin's consolidation of power around 843 CE. Related to this, the term "Scotia" originally denoted the land of the Scoti in Ireland but shifted northward to refer primarily to Scotland by the 11th century, as evidenced in ecclesiastical and papal correspondence. Continental writers initially used "Scotia Maior" for Ireland and "Scotia Minor" for Scotland to differentiate the regions, but by the late 11th century, "Scotia" standalone increasingly meant the northern kingdom in papal documents, such as those acknowledging Scottish sovereignty.[11] This terminological change culminated in 14th-century papal bulls under Pope John XXII, which explicitly applied "Scotia" to the Kingdom of Scotland in diplomatic exchanges, like responses to the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320.[11] In the 12th century, chroniclers like Geoffrey of Monmouth employed "Scoti" pejoratively to describe Celtic peoples north of the Antonine Wall, portraying them as fierce, rebellious northerners allied with Picts in opposition to Britons. In Historia Regum Britanniae, the Scots appear as one of Britain's five nations, often in military contexts—such as Uther Pendragon taming their "fierceness" or Arthur besieging them at Lake Lomond—depicting them as barbarous invaders from the untamed north, embodying a broader disdain for non-Romanized Celts beyond the wall.[12]Historical Role

Roman Encounters

The earliest recorded Roman encounters with the Scoti occurred in the mid-fourth century CE, when they were depicted as Irish raiders launching incursions into Roman Britain, often in alliance with the Picts. In his Res Gestae, the historian Ammianus Marcellinus provides the first specific reference around 360 CE, noting that the "savage tribes of the Scots and the Picts, who had broken the peace that had been agreed upon," were laying waste to frontier regions and instilling fear among the provincials amid ongoing calamities.[13] These raids prompted Emperor Julian to dispatch the general Lupicinus with auxiliary forces, including the Aeruli, Batavians, and Moesians, to reinforce the defenses.[13] The Scoti's threat escalated during the so-called Barbarian Conspiracy of circa 367–368 CE, a coordinated assault on Roman provinces in Britain that included naval incursions from Ireland targeting areas like Valentia, likely corresponding to parts of modern northern England and southern Scotland. Ammianus describes how the Picts—divided into the Dicalydones and Verturiones—the warlike Attacotti, and the Scoti were "ranging widely and causing great devastation," having already killed the Roman commander Nectaridus and captured the duke Fullofaudes, leading to widespread disorder.[14] This multi-front crisis, involving simultaneous attacks by Picts over land and Scoti by sea, exposed vulnerabilities in Roman frontier garrisons and supply lines.[7] In response, Emperor Valentinian I dispatched his general Count Theodosius (father of the future emperor Theodosius I) in late 368 CE to quell the invasions, with campaigns extending into 369 CE that successfully repelled the Scoti-Pictish alliances and recovered captured territories. Ammianus recounts how Theodosius routed the invaders, seized their spoils, and reestablished order by executing traitors and fortifying key sites, thereby portraying the Scoti as a persistent external menace to Roman stability.[15] The term "Scoti" appears in these classical accounts and contemporary panegyrics as a designation for these Irish-based enemies, often alongside the Attacotti, emphasizing their role as recurring threats to the northern frontiers until the Roman withdrawal from Britain around 410 CE.[16]Migration and Settlement

The migration of the Scoti from Ireland to the western seaboard of what is now Scotland commenced with periodic raids in the late 4th and early 5th centuries CE, as documented by Roman writers including Ammianus Marcellinus, who described coordinated assaults by Scoti, Picts, and Saxons on Roman Britain during the "Great Conspiracy" of 367 CE. These incursions, initially predatory, transitioned into more permanent settlements, particularly in the region of Argyll, where the Scoti established the kingdom of Dál Riata by the 6th century. Irish annals, such as the Annals of Tigernach, provide key chronological markers, noting the Scoti's expansion into Britain amid the power vacuum following Roman withdrawal.[17][18] The foundation of Dál Riata is traditionally linked to Fergus Mór mac Eirc, a king from the Irish Dál Riata in County Antrim, who around 498 CE led an expedition to Argyll, securing territory and initiating a dynasty that blended Irish Gaelic political structures and cultural practices with indigenous Pictish elements. The Annals of Tigernach record that in 501 CE, "Fergus Mór son of Earc with the people of Dál Riata held a part of Britain and died there," corroborating this as a pivotal moment of territorial control rather than mere raiding. Subsequent kings from the Cenél nGabráin branch, descendants of Fergus, consolidated power through maritime connections between Ireland and Scotland, fostering a bilingual elite that integrated Gaelic lordship with local traditions.[18][19] Archaeological evidence supports the notion of targeted elite migration over large-scale population displacement. At Dunadd fort, identified as the royal stronghold of Dál Riata from the 5th to 7th centuries, excavations have uncovered Irish-style artifacts such as ogham-inscribed stones, high-status metalwork, and pottery akin to that from Ulster, indicating the arrival of a ruling class that imposed Gaelic symbolism and governance without overwhelming evidence of demographic upheaval. These findings, including a carved footprint possibly used in inauguration rites, highlight the Scoti's establishment of political authority in Argyll through selective settlement and cultural imposition.[20] Interactions between the Scoti and the Picts involved a mix of warfare and diplomacy, with Dál Riata kings like Áed Find (r. 748–778 CE) and Conall mac Taidg (r. 778–810 CE) engaging in battles over borders while forming alliances against common threats such as Viking incursions. This dynamic culminated in 843 CE, when Cináed mac Ailpín, king of Dál Riata, seized the Pictish throne following a period of instability, uniting the two realms into the Kingdom of Alba and establishing Scoti dominance, as reflected in contemporary annals and later chronicles.[21][22]Legacy and Influence

On Scottish Identity

The unification of the Scoti and Picts under Kenneth MacAlpin in 843 CE is regarded as a pivotal moment in the formation of Scotland, known as Alba, where the Scoti's Gaelic-speaking elite assumed dominance over the combined realms.[23] This merger established a centralized kingship that blended Scoti political structures with Pictish territories, laying the groundwork for a unified Scottish identity rooted in Gaelic traditions.[24] Gaelic served as the primary language of the royal court and administration until the 11th century, reinforcing the Scoti's cultural imprint on the emerging kingdom.[25] The Scoti introduced Scottish Gaelic, derived from Old Irish, which became the dominant vernacular across much of medieval Scotland and profoundly shaped its linguistic landscape.[26] This language influenced numerous place names, such as Dundee (from Gaelic Dùn Dè, meaning "fort of the gods" or "fort on the Tay"), reflecting the Scoti's settlement patterns and integration into the topography.[27] It also permeated medieval literature, exemplified by the Duan Albanach (Song of Alba), a 11th-century Gaelic poem that chronicled the kings of Scots from their Irish origins, thereby embedding Scoti heritage in Scotland's literary canon.[28] In Scottish mythology and historiography, the Scoti held a foundational role, with medieval genealogies tracing the lineage of Scottish kings back to Irish Scoti figures like Fergus Mór, emphasizing a continuous Celtic lineage from Ireland to Alba.[29] These narratives, preserved in texts such as the Senchus fer n-Alban, portrayed the Scoti as the progenitors of the Scottish people, fostering a sense of national continuity and ethnic pride.[30] This symbolic legacy underscored the Scoti's contribution to a cohesive identity that celebrated Gaelic roots amid diverse regional influences. The enduring significance of the Scoti is evident in official medieval documents, such as the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320, which proclaimed Scotland as the "regnum Scotorum" (kingdom of the Scots), invoking their ancient heritage to assert sovereignty and independence.[31] This usage of "Scoti" in Latin titles affirmed the term's evolution to denote the inhabitants of the unified kingdom, solidifying their central place in Scotland's self-conception.[32]Modern Scholarship

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, romantic nationalism shaped popular and scholarly perceptions of the Scoti, often depicting them as heroic Irish migrants who boldly crossed the Irish Sea to establish Gaelic kingdoms in western Scotland, such as Dál Riata, thereby founding a unified Scottish identity. This narrative, influenced by literary figures like Sir Walter Scott in works such as Waverley (1814) and his broader romanticization of Highland clans and ancient lineages, emphasized epic migrations and cultural triumphs to foster national pride amid British unionism. However, these portrayals have been widely critiqued since the mid-20th century for relying on anachronistic myths and selective medieval chronicles rather than empirical evidence, with historians arguing that they projected Victorian ideals onto sparse ancient sources. Archaeological research from the late 20th and early 21st centuries has significantly revised these traditional invasion models, revealing limited evidence for large-scale Scoti migration and favoring interpretations of gradual cultural diffusion. Key studies, including Ewan Campbell's analysis in Antiquity (2001), examined material culture in Argyll and found no significant Irish imports or settlement discontinuities around the 5th–6th centuries CE, attributing Gaelic linguistic and artistic spread to elite exchanges and maritime contacts rather than mass population movements. Publications by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in the 2000s, such as those in the Proceedings, further supported this by highlighting continuity in local pottery and settlement patterns, suggesting that Scoti influence operated through networks of trade and alliance rather than conquest. Complementing this, genetic analyses of Y-DNA haplogroups, particularly R1b-L21 prevalent in both Ireland and Scotland, indicate shared ancestry from earlier Bronze Age dispersals, reinforcing models of cultural adoption over demographic replacement during the early medieval period.[33][34] Contemporary debates on Scoti ethnicity increasingly apply post-colonial frameworks to interrogate Roman sources, which often framed the Scoti as savage raiders to justify imperial defenses, thereby embedding ethnic stereotypes that persisted in later historiography.[35] Scholars like Ralph Hingley have analyzed these biases as tools of Roman "othering," arguing that texts from Ammianus Marcellinus and others exaggerated Scoti threats to legitimize provincial control, distorting neutral interactions into narratives of barbarism. Barry Cunliffe's 21st-century works, such as The Extraordinary Voyage of Pytheas the Greek (2001) and broader Atlantic studies, counter this by emphasizing interconnected maritime networks across the Irish Sea from the Iron Age onward, portraying Scoti activities as part of fluid, non-conquest-based exchanges in a "Celtic" sea zone rather than isolated invasions. Recent DNA research in the 2020s confirms strong Irish-Scottish genetic affinities but traces them primarily to continental migrations around 2500–2000 BCE, not medieval Scoti movements alone, thus challenging ethnic origin myths tied to later historical events.[36]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Scoti