Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chilote Spanish

View on Wikipedia| Chilote Spanish | |

|---|---|

| Chilote, castellano chilote | |

| Pronunciation | [tʃiˈlote], [kasteˈʝano tʃiˈlote] |

| Native to | Chiloé Archipelago, Chile and vicinity. |

| Ethnicity | Chilote Chileans |

Early forms | |

| Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Chilote is a dialect of Spanish language spoken on the southern Chilean islands of Chiloé Archipelago (Spanish: Archipiélago de Chiloé or simply, Chiloé). It has distinct differences from standard Chilean Spanish in accent, pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary, especially by influences from local dialect of Mapuche language (called huilliche or veliche) and some conservative traits.

It is considered one of the four zones into which Chilean Spanish is divided,[1][a] where it is regarded as “the most significant […] because of the archaic character of its language.”[2]

History

[edit]The indigenous population of Chiloé was composed of the Huilliches, Payos, and Chonos; the first two spoke Veliche, the Chiloé dialect of Mapudungun, while the Chonos had their own language, about which almost nothing is known.

In the mid-16th century, Chiloé was colonized by the Spanish, who upon arriving on the Isla Grande named it “Nueva Galicia” because of its landscape’s similarity to that Spanish region.[3] The archipelago was the last domain of the Spanish Crown in what is now Chilean territory; it was incorporated into the Republic of Chile in 1826 through the Treaty of Tantauco, following the patriot victory in the so-called “Conquest of Chiloé.”

The conquerors founded towns and subjected the indigenous population to labor under the encomienda system, but the conditions of isolation from other colonies soon led to a process of mestizaje among the different ethnic groups. After the Battle of Curalaba (1598), which resulted in the destruction or depopulation of cities between the Biobío River and the Chacao Channel, the Spanish population of the archipelago became even more isolated. For this reason, the inhabitants of the archipelago were left to rely on their own resources and, over time, developed a culture of their own, in which language also took on a distinctive form. During the 17th and 18th centuries, most of the population was bilingual and, according to the English castaway John Byron, many Spaniards preferred to use the Huilliche language because they considered it “more beautiful.”[4] Around the same time, Governor Narciso de Santa María complained that Spaniards spoke Spanish poorly and Veliche well, and that the latter language was used more frequently.[5]

After the expulsion of the Jesuits by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1767, the new religious orders encouraged the use of Spanish, and by the end of the 18th century a priest noted that there was already greater familiarity with the Spanish language—among Spaniards and mestizos as well as among indigenous people—although confessions continued to be conducted in Veliche. Although this dialect disappeared by the end of the 19th century, the Spanish spoken in Chiloé shows strong influence from it in vocabulary and in certain grammatical constructions; it also contains many archaisms from the Spanish spoken during the colonial period, long since obsolete in other varieties of the language, to the point that at the beginning of the 20th century a Chilean traveler claimed not to understand the language spoken by some Chilote boatmen in a port. However, today uniform education, the presence of mass media that use standard Spanish or Chilean Spanish, and the low prestige of Chilote Spanish have led to fewer and fewer Chilotes using their local speech, to the point that many people are not understood when they do so.

Phonology

[edit]- As in Chilean Spanish, the /s/ is aspirated at the end of the syllable and the /d/ between vowels tends to be removed.

- Aspirated realization of "j" as [h].

- Transformation of the groups [bo, bu] and [ɡo, ɡu] into [wo, wu].

- Preservation of the nasal consonant velar /ŋ/ (written "ng" or "gn") in words of Mapuche origin. This phoneme does not exist in standard Spanish. Eg: culenges [kuˈleŋeh] (In the rest of Chile, it is said culengues [kuˈleŋɡeh]).

- Difference in treatment for "y" and "ll" : From Castro to the north, no difference is made between them, since both are pronounced as [ʝ] (yeísmo). In sectors of the center and the south they are pronounced differently, they can be [ʝ] and [dʒ], [ʝ] and [ʒ] or [dʒ] and [ʒ]. There are also other places in the southern and western parts where they are both pronounced [ʒ].

- It is common for "ch" to be pronounced as a fricative [ʃ], similar to an English "sh". This fricative pronunciation has a social stigma associated in Chile, but not so much in the northernmost regions where speakers may go back and forth between /tʃ/ and [ʃ].

- In some places the group "tr" is pronounced differently according to the etymology of the word: if it comes from Spanish, both consonants are clearly pronounced, while if the word comes from Mapudungun, it is pronounced [tɹ], similar to a "chr". However, in the rest of the places, the words of Mapuche origin that had this consonant have replaced it by the "chr" and in the rest this group is pronounced [tɾ] as in most dialects of Spanish, unlike what occurs in Chilean Spanish, in which you tend to use [tɹ] regardless of the origin of the word.

- Paragoge: A vowel is added to the end of words ending in "r" or "c". Eg: andar [anˈdarə], Quenac [keˈnakə].

- The prosodic aspects of Chiloé Spanish have recently been studied and show an ascending intonation.[6]

Morphology

[edit]The Spanish of the Chiloé Archipelago shares a number of morphological characteristics with that of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado and with that of rural areas of the Mexican states of Chihuahua, Durango, Sonora, Tlaxcala, Jalisco, and Guanajuato:[7]

- Second-person preterite forms ending in -ates, -ites instead of the standard -aste, -iste.

- Latin -b- is retained in some imperfect conjugations of -er and -ir verbs, with the preceding -i- diphthongized into the previous vowel, as in: caiban vs. caían, traiba vs. traía, creiban vs creían.

- Verbs ending in -er are, like those ending in -ir, conjugated in -imos for both the present and preterite tenses. The reverse occurs in New Mexico and rural Mexico, where -ir verbs can be conjugated -emos in the present tense.

- Non-standard -g- in many verb roots, such as creiga 'believe'.

- In their present-tense subjunctive first person plural conjugations, verbs are pronounced with stress on the antepenultimate syllable, instead of on the penultimate one, thus váyamos and báilemos instead of vayamos and bailemos.

- The clitic pronoun nos 'we' is often replaced by los. This is found in Traditional New Mexican Spanish but is not attested within Mexico.

Syntax and grammar

[edit]- There is a strong predominance of tuteo (use of tú),[8][9][10] with limited presence of voseo in the River Plate and Chilean styles, which has been spreading from central Chile.[11] In familiar address, the hybrid form Tú soes is used. In the imperfect future, voseo conjugations with the ending -is are used instead of the standard -ás; this also occurs in the simple past, where the first -s of the verb is dropped and the final one is retained[12]—a feature also found in varieties of Colombia and the Venezuelan Andes: cantarís, comerís, vendrís, anduvites, comites, oítes.

- In respectful address, the second person plural ustedes is used, with its corresponding verb conjugation, instead of the singular usted: ¿Ustedes son don Luis Bórquez?

- The definite article is used before female proper names: la Cecilia.

- Qué is used at the end of interrogative sentences that require a yes/no answer: ¿Ya llegarían qué?

- The verb dejar is combined with a past participle to indicate an action completed immediately before another: ¿Dejarían almorzado qué? — No, dejé desayunado no más y salí.

- Na (< nada) is used to reinforce negation: Yo no soy na esa persona.

- Independent stress is placed on clitics in imperative forms with a direct object and on the clitics -se and -te:[8] da-melo, come-tela, di-selo, caer-se, sienta-te.

- The first-person plural of the imperfect past is stressed on the penultimate syllable:[8] trabajabamos, decíamos.

- The -r of the infinitive is dropped when followed by clitics beginning with l:[8] dalo, tenelo, urdilo.

- Lo is used as a direct object in place of la:[8] — ¿Él traería la madera qué? — Sí, lo trajo.

- The preposition a is used to indicate the location of actions in progress: Su papá anda a Castro.

- In some areas, the diminutive suffix is -icho, -icha: viejicho, perricha.

- The listener is “included” when narrating events in which they do not participate: Aquel chico todo lo que tiene te lo rompe (“That boy breaks everything he has”); ¿Quién te sabrá? (“Who knows?”).

- In comparisons, the pronouns yo and tú are replaced by mí and ti; conversely, conmigo and contigo are not used, but rather the regular forms con yo and con tú. These expressions are strongly discouraged in schools, as they are considered completely incorrect from the point of view of the standard language: Tú cantas mejor que a mí,[8] es más alta que a ti, tienes que venir con yo.

- The verbs querer and doler are conjugated in the future in the same way as poder: quedrís, doldrá.

Varieties

[edit]There is an undetermined number of varieties that form a continuum in which differences accumulate as the distance between them increases. They are distinguished by intonation, pronunciation, and vocabulary. Therefore, the phonological and grammatical features mentioned above do not apply to all varieties. It is common for a person from Chiloé to be able to identify another’s place of origin by the way they speak, although today the differences are much less pronounced than they were a few decades ago.

Vocabulary

[edit]The vocabulary contains a large proportion of Huilliche words, as well as archaisms and regionalisms brought from Spain. The meanings of some terms have also changed, and new ones have been created. In addition, terms common to other regions of Hispanic America are preserved that in the rest of Chile have been replaced by local expressions.

Huilliche words

[edit]Words of Huilliche origin mainly refer to native plants and animals, traditional agricultural activities—such as potato cultivation—or to food (whose staple is the potato). Many words that in modern Mapudungun contain tr change it to ch here.

Verbs of Mapuche origin are formed by adding the auxiliary hacer (“to do/make”).

- chehua (dog),

- chelle (Larus maculipennis),

- hacer meño (to behave in a way very different from one’s usual behavior; it is believed to be an omen of death),

- huele (left-handed),

- llevar a cheque or hacer cheque (to carry someone on one’s back),

- pachanca (penguin),

- pilcahue (a sweet-tasting potato that comes from a plant that produced a tuber left in the ground without being harvested).

Quechua loanwords

[edit]Alongside terms of Quechua origin that are in common use throughout Chile—such as choclo, cochayuyo, or guagua—there are words of Quechua origin whose use is restricted to Chiloé and neighboring areas, such as cochaguasca or minga.

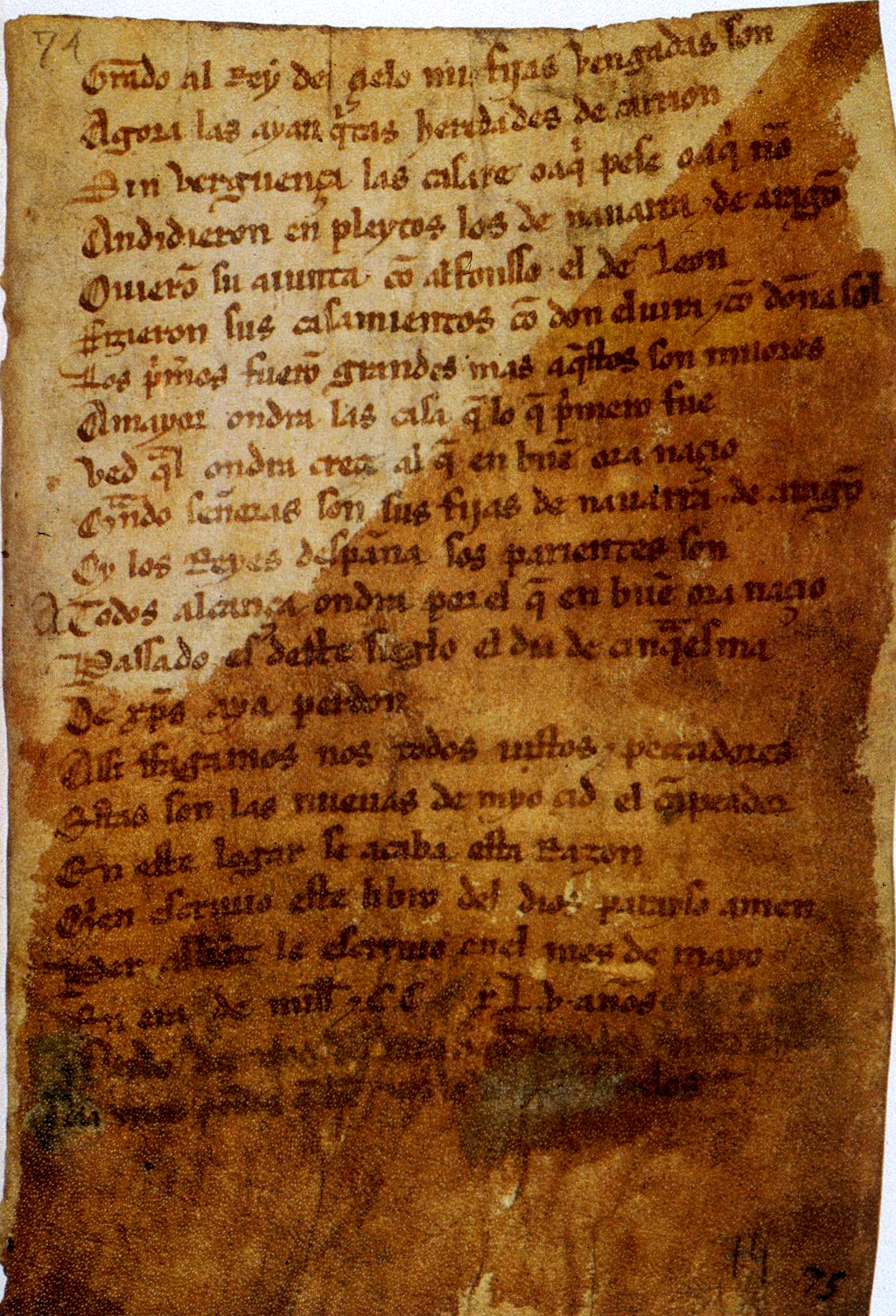

Spanish archaisms and regionalisms

[edit]- agora (now),

- ansina (thus/so),

- chiquinino (very small),

- leste (east wind),

- peseta (coin),

- preba (test),

- ueste (west wind), among others.

Changes in meaning

[edit]- curioso (knowledgeable about a topic),

- hombre soltero (young adult),

- mentira (trifle),

- privarse (to become enraged),

- sapo (insect),

- valiente (hard-working).

Studies

[edit]The first researcher to publish works on the Spanish of Chiloé was the priest Francisco Cavada, who compiled dictionaries and recorded a series of grammatical features that he regarded as errors or deviations from correct Spanish, as well as others in which the speech of Chiloé resembled the standard language and therefore differed from the speech of other areas of Chile. Other researchers—mostly compilers of dictionaries and lexical lists—have included Elena Quintana, Nicasio Tangol, and Renato Cárdenas.

References

[edit]- ^ Francisco Moreno Fernández points out that each zone has specific names for the varieties that make it up: the northern zone (Tarapaqueño and Coquimbano), the central zone (Colchagüino), the southern zone (Pencón), and the south-austral zone (Chilote).

- ^ Rabanales 2000, p. 136-137.

- ^ Rabanales 2000, p. 136.

- ^ Jayme, Javier (18 April 2013). "Descubriendo Chiloé: Así es la Galicia chilena". ABC (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 February 2026.

Los españoles, al tomar posesión de ella en 1567, la llamaron Nueva Galicia por su similitud paisajística con la región galaica de nuestra Península Ibérica.

[When the Spanish took possession of it in 1567, they named it Nueva Galicia (New Galicia) because of its similarity in landscape to the Galician region of our Iberian Peninsula.] - ^ Byron, John (1955). El naufragio de la fragata "Wager". Santiago: Zig-Zag.

- ^ Cárdenas, Renato; Montiel, Dante; Hall, Catherine (1991). Los chono y los veliche de Chiloé. Santiago: Olimpho. p. 277.

- ^ Muñoz-Builes, Diana; Ramos, Dania; Román, Domingo; Quezada, Camilo; Ortiz-Lira, Héctor; Ruiz, Magaly; Atria, José Joaquin (2017). "El habla ascendente de Chiloé: primera aproximación". Onomázein (17): 1–15. doi:10.7764/onomazein.37.01.

- ^ Sanz, Israel; Villa, Daniel J. (2011). "The Genesis of Traditional New Mexican Spanish: The Emergence of a Unique Dialect in the Americas". Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics. 4 (2): 417–442. doi:10.1515/shll-2011-1107. S2CID 163620325. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Cavada, Francisco J. (1914). "Estudios lingüísticos". Chiloé y los chilotes. Santiago: Imprenta Universitaria. p. 448.

- ^ Jaramillo, June (1996). "Los pronombres de tratamiento tú y usted en el español de Tucson, Arizona". Tercer Encuentro de Lingüística en el Noroeste. Hermosillo: Universidad de Sonora. p. 255. ISBN 968-7713-01-1.

- ^ Bishop, Kelley; Michnowicz, Jim. "Forms of address in Chilean Spanish". Hispania. 93 (3): 413–429. ISSN 0018-2133.

- ^ Rivadeneira Valenzuela, Marcela (2009). El voseo en medios de comunicación de Chile. Descripción y análisis de la variación dialectal y funcional. Tesis doctoral. Barcelona: Universidad Pompeu Fabra.

- ^ Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. "voseo". Royal Spanish Academy (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 February 2026.

Bibliography

[edit]- Moreno Fernández, Francisco (2014). La lengua española en su geografía. Madrid: Arco/Libros.

- Rabanales, Ambrosio (2000). "El español de Chile: Presente y futuro". Onomázein. 5: 135–141.

- Cavada, Francisco J. (1914). Chiloé y los chilotes. Santiago: Imprenta Universitaria. p. 448.

- Montiel Vera, Dante; Gómez Vera, Carlos (1992). "El español en Chiloé". Chiloé a 500 años: texto consultivo para la educación media chilena. Santiago: Gobernación Provincial de Chiloé.