Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Voseo

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

In Spanish grammar, voseo (Spanish pronunciation: [boˈseo]) is the use of vos as a second-person singular pronoun, along with its associated verbal forms, in certain regions where the language is spoken. In those regions it replaces tuteo, i.e. the use of the pronoun tú and its verbal forms. Voseo can also be found in the context of using verb conjugations for vos with tú as the subject pronoun (verbal voseo).[1]

In all regions with voseo, the corresponding unstressed object pronoun is te and the corresponding possessive is tu/tuyo.[2]

Vos is used extensively as the second-person singular[3] in Rioplatense Spanish (Argentina and Uruguay), Chilean Spanish, Eastern Bolivia, Paraguayan Spanish, and much of Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica); in Mexico, in the southern regions of Chiapas and parts of Oaxaca. It is rarely used, if at all, in places such as Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Vos had been traditionally used in Argentina, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Paraguay, the Philippines and Uruguay, even in formal writing. In the dialect of Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay (known as 'Rioplatense'), the usage of vos is prevalent, even in mainstream film, media and music. In Argentina, particularly from the second half of the 20th century, it has become very common to see billboards and other advertising campaigns using voseo.[4][5]

Vos is present in some regions of other countries, for instance in the Maracucho Spanish of Zulia State, Venezuela (see Venezuelan Spanish), the Azuero Peninsula of Panama, in a few departments in Colombia,[6] and in parts of Ecuador (Sierra down to Esmeraldas). In Peru, voseo is present in certain Andean regions and Cajamarca, but the younger generations have ceased to use it. It is also present in Judaeo-Spanish, spoken by Sephardic Jews, where it is the archaic plural form that vosotros replaced.

Voseo is seldom taught to students of Spanish as a second language, and its precise usage varies across different regions.[7] Nevertheless, in recent years, it has become more commonly accepted across the Hispanophone world as a valid part of regional dialects.

History

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

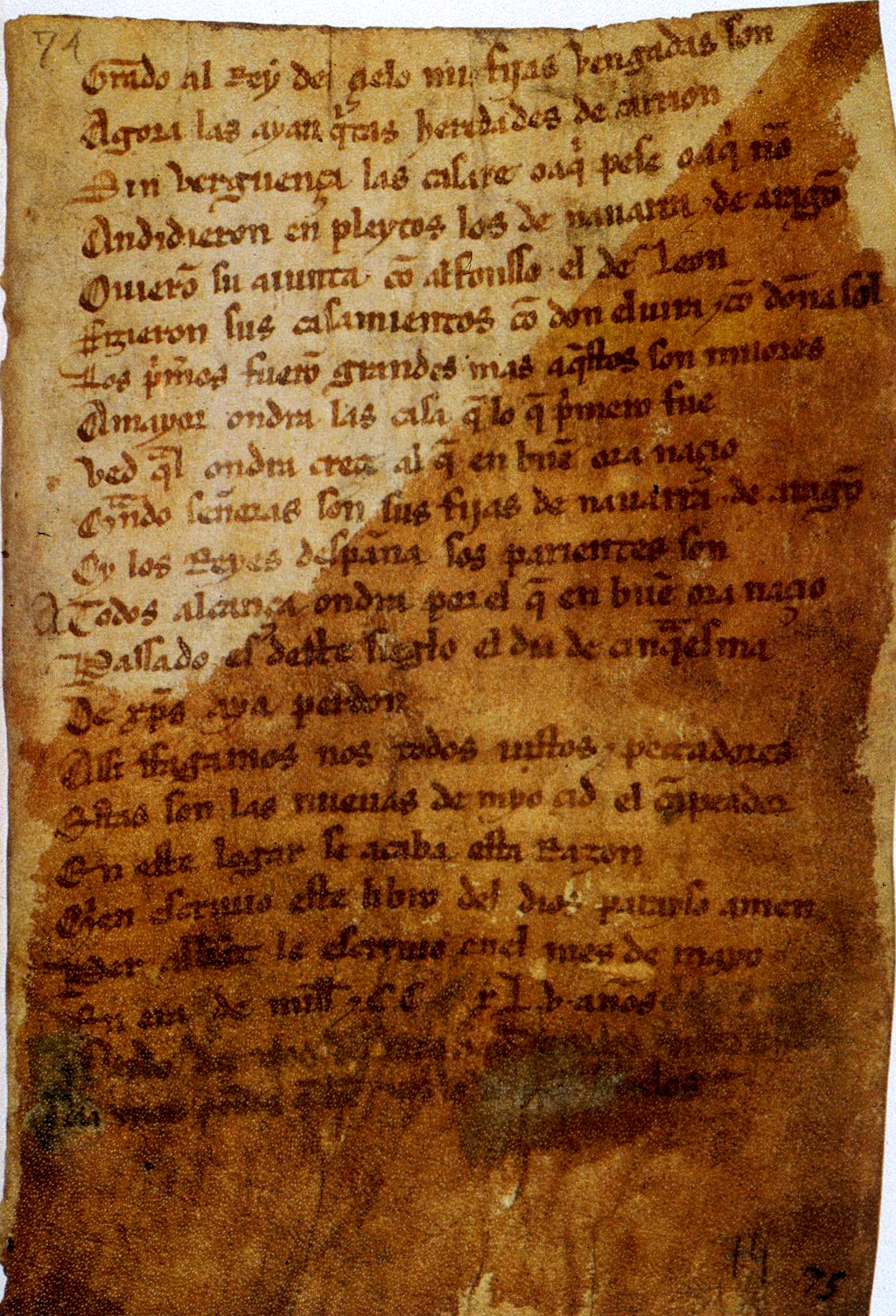

Classical Latin, and the Vulgar Latin from which Romance languages such as Spanish are descended, had only two second-person pronouns – the singular tu and the plural vos. Starting in the early Middle Ages, however, languages such as French and Spanish began to attach honorary significance to these pronouns beyond literal number. Plural pronouns were often used to refer to a person of respect to aggrandize them. Vos, the second-person plural inherited from Latin, came to be used in this manner.

Already by the late 18th century, however, vos itself was restricted to politeness among one's familiar friends. The following extract from a textbook is illustrative of usage at the time:

We seldom make use in Spanish of the second Person Singular or Plural, but when through a great familiarity among friends, or speaking to God, or a wife and husband to themselves, or a father and mother to their children, or to servants.

Examples.

O Dios, sois vos mi Padre verdadéro, O God, thou art my true Father; Tú eres un buen amígo, Thou art a good friend.

— Raymundo del Pueyo, A New Spanish Grammar, or the Elements of the Spanish Language[8]

The standard formal way to address a person one was not on familiar terms with was to address such a person as vuestra merced ("your grace", originally abbreviated as v.m.) in the singular and vuestras mercedes in the plural. Because of the literal meaning of these forms, they were accompanied by the corresponding third-person verb forms. Other formal forms of address included vuestra excelencia ("your excellence", contracted phonetically to ussencia) and vuestra señoría ("your lordship/ladyship", contracted to ussía). Today, both vos and tú are considered to be informal pronouns, with vos being somewhat synonymous with tú in regions where both are used. This was the situation when the Spanish language was brought to the Río de la Plata area (around Buenos Aires and Montevideo) and to Chile.

In time, vos lost currency in Spain but survived in a number of areas in Spanish-speaking America: Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia (east), Uruguay, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and some smaller areas; it is not found, or found only in internally remote areas (such as Chiapas) in the countries historically best connected with Spain: Mexico, Panama, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Equatorial Guinea. Vuestra merced evolved into usted: vuestra merced > usarced > usted; in fact, usted is still abbreviated as either Vd or Ud). Note that the term vosotros is a combined form of vos otros (meaning literally 'ye/you others'), while the term nosotros comes from nos otros ("we/us others").

In the first half of the 19th century, the use of vos was as prevalent in Chile as it was in Argentina. The current limitation of the use of vos in Chile is attributed to a campaign to eradicate it by the Chilean education system. The campaign was initiated by Andrés Bello who considered the use of vos a manifestation of lack of education.[9]

Usage

[edit]Vos in relation to other forms of tú

[edit]The independent disjunctive pronoun vos also replaces ti, from the tuteo set of forms. That is, vos is both nominative and the form to use after prepositions. Therefore, para vos ("for you") corresponds to the tuteo form para ti, etc.

The preposition-pronoun combination con vos ("with you") is used for the tuteo form contigo.

The direct and indirect object form te is used in both voseo and tuteo.[2]

| Nominative | Oblique | Reflexive | |||||

| subject | direct object | indirect object | prepositional object | fused with con | direct/indirect object | prepositional object | fused with con |

| vos | te | te | vos | con vos | te | vos | con vos |

| usted | lo/la | le | usted | con usted | se | sí | consigo |

| tú | te | te | ti | contigo | te | ti | contigo |

| vosotros | os | os | vosotros | con vosotros | os | vosotros | con vosotros |

The possessive pronouns of vos also coincide with tú <tu(s), tuyo(s), tuya(s)> rather than with vosotros <vuestro(s), vuestra(s)>.[2]

Voseo in Chavacano

[edit]Chavacano, a Spanish-based creole spoken in the Philippines, employs voseo,[10][11] while the standard Spanish spoken in the country does not.[12] The Chavacano language below in comparison of other Chavacano dialects and level of formality with Voseo in both subject and possessive pronouns. Note the mixed and co-existing usages of vos, tú, usted, and vosotros.

| Zamboangueño | Caviteño | Bahra | Davaoeño (Castellano Abakay) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd person singular | vos/vo/evo/evos (common/informal) tú (familiar) usted (formal) |

vo/bo (common) tu (familiar) usté (formal) |

vo/bo (common/informal) usté (formal) |

usted (formal)

vos (informal) |

| 2nd person plural | kamó (common) vosotros (familiar) ustedes (formal) |

vusos busos |

buhotro bujotro ustedi tedi |

ustedes

vosotros |

| Zamboangueño | Davaoeño (Castellano Abakay) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2nd person singular | de vos (common) de tu (familiar) tuyo (familiar) de tuyo/di tuyo (familiar) de usted (formal) |

de tu |

| 2nd person plural | de iño/di inyo (common) de vosotros (familiar) de ustedes (formal) |

(de) vos |

Conjugation with vos

[edit]All modern voseo conjugations derive from Old Spanish second person plural -ades, -edes, -ides, and -odes (as in sodes, 'you are').[13] The 14th and 15th centuries saw an evolution of these conjugations, with -ades originally giving -áis, -edes giving -és (or -ís),[13][14] -ides giving -ís,[15] and -odes giving -óis.[13] Soon analogous forms -ás and -éis appeared.[13] Hence the variety of forms the contemporary American voseo adopts, some varieties featuring a generalized monophthong (most of them), some a generalized diphthong (e.g. Venezuela), and some combining monophthongs and diphthongs, depending on the conjugation (e.g. Chile). In the most general, monophthongized, conjugation paradigm, a difference between voseo forms and respective tuteo forms is visible exclusively in the present indicative, imperative and subjunctive, and, most of the time, in the preterite.[14] Below is a comparison table of the conjugation of several verbs for tú and for vos, and next to them the one for vosotros, the informal second person plural currently used orally only in Spain; in oratory or legal language (highly formal forms of Spanish) it is used outside of Spain. Verb forms that agree with vos are stressed on the last syllable, causing the loss of the stem diphthong in those verbs, such as poder and venir, which are stem-changing.

| Verb | Tú 2. Sg. |

Vos General |

Tú/Vos Chile1 |

Vos Southeastern Cuba, Northeastern Colombia1, 2, Venezuela3 and Panama4 |

Vosotros 2. Pl. in Spain |

Vosotros – בֿוֹזוֹטרוֹז general 2.Pl And Vos – בֿוֹז formal 2.Sg Ladino |

Ustedes 2. Pl |

Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ser | eres | sos | erís/sois | sois | sosh סוֹש /soʃ/ | son | you are | ||

| comer | comes | comés | comís | coméis | komesh קוֹמֵיש /koˈmeʃ/ | comen | you eat | ||

| poder | puedes | podés | podís | podéis | podesh פּוֹדֵיש /poˈdeʃ/ | pueden | you can/may | ||

| hablar | hablas | hablás | hablái | habláis | favlash פֿאבֿלאשׁ /faˈvlaʃ/ | hablan | you speak | ||

| recordar | recuerdas | recordás | recordái | recordáis | recordash רֵיקוֹרדאשׁ /rekorˈdaʃ/ | recuerdan | you remember | ||

| vivir | vives | vivís | bivish בִּיבִֿיש /biˈviʃ/ | viven | you live | ||||

| venir | vienes | venís | venish בֵֿינִיש /veˈniʃ/ | vienen | you come | ||||

| 1 Because of the general aspiration of syllable-final [s], the -s of this ending is usually heard as [h] or not pronounced. 2 In Colombia, the rest of the country that uses vos follows the General Conjugation. 3 In the state of Zulia 4 in Azuero | |||||||||

General conjugation is the one that is most widely accepted and used in various countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, parts of Bolivia, Ecuador, and Colombia, as well as Central American countries.[2]

Some Uruguayan speakers combine the pronoun tú with the vos conjugation (for example, tú sabés).[2] Conversely, speakers in some other places where both tú and vos are used combine vos with the tú conjugation (for example, vos sabes).[2] This is a frequent occurrence in the Argentine province of Santiago del Estero.

The verb forms employed with vos are also different in Chilean Spanish: Chileans use -ái and soi 'you are' instead of -áis or -ás and sois or sos. Chileans never pronounce these conjugations with a final -s. The forms erís for 'you are', and habís and hai for 'you have' are also found in Chilean Spanish.[16]

In the case of the ending -ís (such as in comís, podís, vivís, erís, venís), the final -s is pronounced like any other final /s/ in Chilean Spanish. It is most often pronounced as an aspiration similar to the 'h' sound in English. It can also be pronounced as a fricative [s], or be dropped completely. Its variable pronunciation is a phonological rather than a morphological phenomenon.[16]

Venezuelan Maracucho Spanish is notable in that they preserve the diphthongized plural verb forms in all tenses, as still used with vosotros in Spain.[2] Chilean Spanish also notably uses the diphthong -ái.

In Ladino, the -áis, -éis, -ís, & -ois endings are pronounced /aʃ/, /eʃ/, /iʃ/, & /oʃ/.

In Chile, it is much more usual to use tú + vos verb conjugation (tú sabís). The use of pronominal vos (vos sabís) is reserved for very informal situations and may even be considered vulgar in some cases.[2]

Present indicative

[edit]- General conjugation: the final -r of the infinitive is replaced by -s; in writing, an acute accent is added to the last vowel (i.e. the one preceding the final -s) to indicate stress position.

- Chilean:

- the -ar ending of the infinitive is replaced by -ái

- both -er and -ir are replaced by -ís, which sounds more like -íh.

- Venezuelan (Zulian): practically the same ending as modern Spanish vosotros, yet with the final -s being aspirated so that: -áis, -éis, -ís sound like -áih, -éih, -íh (phonetically resembling Chilean).

| Infinitive | Present Indicative | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General | Venezuelan1 | Chilean | |

| oír | oís | ||

| venir | venís | ||

| decir | decís | ||

| dormir | dormís | ||

| sentir | sentís | ||

| escribir | escribís | ||

| concluir | concluís | ||

| ir | vas | vais | vai(s) |

| pensar | pensás | pensáis | pensái |

| contar | contás | contáis | contái |

| jugar | jugás | jugáis | jugái |

| errar | errás | erráis | errái |

| poder | podés | podéis | podís |

| querer | querés | queréis | querís |

| mover | movés | movéis | movís |

| saber | sabés | sabéis | sabís |

| ser | sos | sois | soi/erís |

| haber | has | habéis | habís/hai |

| 1 in Zulia; identical ending to modern vosotros | |||

Unlike tú, which has many irregular forms, the only voseo verbs that are conjugated irregularly in the indicative present are ser, ir and haber. However, haber is seldom used in the indicative present, since there is a strong tendency to use preterite instead of present perfect.

Affirmative imperative

[edit]Vos also differs in its affirmative imperative conjugation from both tú and vosotros. Specifically, the vos imperative is formed by dropping the final -r from the infinitive, but keeping the stress on the last syllable.[13] The only verb that is irregular in this regard is ir; its vos imperative is not usually used, with andá (the vos imperative of andar, which is denoted by *) being generally used instead; except for the Argentine province of Tucumán, where the imperative ite is used. For most regular verbs ending in -ir, the vos imperatives use the same conjugations as the yo form in the preterite; almost all verbs that are irregular in the preterite (which are denoted by ‡) retain the regular vos imperative forms.

| Verb | Meaning | Tú | Vos | Vosotros (written) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ser | to be | sé | sé | sed |

| estar | to be | está/estate | está/estate | estad |

| ir | to go | ve | i/ite[17][18] *(andá/andate) | id |

| hablar | to speak | habla | hablá | hablad |

| callar | to become silent | calla | callá | callad |

| soltar | to release/let go | suelta | soltá | soltad |

| comer | to eat | come | comé | comed |

| mover | to move | mueve | mové | moved |

| venir | to come | ven | vení ‡ | venid |

| poner | to put | pon | poné | poned |

| salir | to leave | sal | salí | salid |

| tener | to have | ten | tené | tened |

| decir | to say | di | decí ‡ | decid |

| pedir | to ask/order | pide | pedí | pedid |

Again, the conjugation of tú has far more irregularities, whereas vos has only one irregular verb in the affirmative imperative.

In Chile, the general vos conjugation is not used in the affirmative imperative.

Subjunctive

[edit]In most places where voseo is used, it is applied also in the subjunctive. In the Río de la Plata region, both the tú-conjugation and the voseo conjugation are found, the tú-form being more common. In this variety, some studies have shown a pragmatic difference between the tú-form and the vos-form, such that the vos form carries information about the speaker's belief state, and can be stigmatized.[19][20] For example, in Central America the subjunctive and negative command form is no mintás, and in Chile it is no mintái; however, in Río de la Plata both no mientas and no mintás are found. Real Academia Española models its voseo conjugation tables on the most frequent, unstigmatized Río de la Plata usage and therefore omits the subjunctive voseo.[21]

| Central America1 Bolivia |

Río de la Plata region | Chile | Venezuela (Zulia) Panama (Azuero) |

meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No quiero que mintás. | No quiero que mientas. | No quiero que mintái. | No quiero que mintáis. | I don't want you to lie. |

| No temás. | No temas. | No temái. | No temáis. | Do not fear. |

| Que durmás bien | Que duermas bien. | Que durmái bien. | Que durmáis bien. | Sleep well. |

| No te preocupés. | No te preocupes. | No te preocupís. | No te preocupéis. | Don't worry. |

| 1including areas in Colombia with voseo, e.g. the Paisa region. | ||||

Verbal voseo and pronominal voseo

[edit]- 'Verbal voseo' refers to the use of the verb conjugation of vos regardless of which pronoun is used.[2]

- Verbal voseo with a pronoun other than vos is widespread in Chile, in which case one would use the pronoun tú and the verb conjugation of vos at the same time. E.g.: tú venís, tú escribís, tú podís, tú sabís, tú vai, tú estái.

- There are some partially rare cases of a similar sort of verbal voseo in Uruguay where one would say for example tú podés or tú sabés.

- 'Pronominal voseo' is the use of the pronoun vos regardless of verb conjugation.[2]

Geographical distribution

[edit]

Countries where voseo is predominant

[edit]

In South America:

- Argentina – both pronominal and verbal voseo, the pronoun tú is not preferred.[2]

- Paraguay – both pronominal and verbal voseo,[2] the pronoun tú is uncommon in most of the country.

- Uruguay – dual-usage of both pronominal and verbal voseo and a combination of the pronoun tú + verb conjugated in the vos form,[2] except near the Brazilian border, where only pronominal and verbal tuteo is common.

In Central America:

- Guatemala – three-tiered system is used to indicate the degree of respect or familiarity: usted, tú, vos. Usted expresses distance and respect; tú corresponds to an intermediate level of familiarity, but not deep trust; vos is the pronoun of maximum familiarity and solidarity. Pronominal tú is frequent with verbal voseo.[2]

- Honduras – three-tiered system is used to indicate the degree of respect or familiarity: usted, tú, vos. Usted expresses distance and respect; tú corresponds to an intermediate level of familiarity, but not deep trust; vos is the pronoun of maximum familiarity and solidarity.[2]

- Nicaragua – both pronominal and verbal voseo throughout all social classes; tú is mostly used in writing.[2]

- Costa Rica – voseo has historically been used, back in the 2000s it was losing ground to ustedeo and tuteo, especially among younger speakers.[22] Vos is now primarily used orally with friends and family in Cartago, Guanacaste province, the San José metropolitan area and near the Nicaraguan border and in advertising signage. Usted is the primary form in other areas and with strangers. Tuteo is rarely used, but when it is used in speech by a Costa Rican, it is commonly considered fake and effeminate.[23]

- El Salvador – three-tiered system is used to indicate the degree of respect or familiarity: usted, tú, vos. Usted expresses distance and respect; tú corresponds to an intermediate level of familiarity, but not deep trust; vos is the pronoun of maximum familiarity and solidarity and also lack of respect.[24]

Countries where voseo is extensive, but not predominant

[edit]In South America:

- Bolivia – in the Lowlands of Eastern Bolivia—with mestizo, Criollo and German descendants majority—(Santa Cruz, Beni, Pando, Tarija and the Lowlands of La Paz) voseo is used universally; while in the Highlands of Western Bolivia—with indigenous peoples majority—(highlands of La Paz, Oruro, Potosí, Chuquisaca and Cochabamba) tú is predominant, but there is still a strong use of voseo, especially in verb forms.

- Chile – verbal voseo and pronominal tú is used in informal situations, whereas pronominal voseo is reserved only for very intimate situations or to offend someone. In every other situation and in writing, the normal tú or usted pronouns are used.

Countries where voseo occurs in some areas

[edit]In the following countries, voseo is used only in certain areas:

- Colombia – in the following departments:

- In the west (along the Pacific coast):

- In the center – primarily the Paisa region (Antioquia, Risaralda, Quindío, and Caldas Departments).

- In the (north)east:

- Cuba – in Camagüey Province, often used alongside tú.

- Ecuador – in the Sierra, the center, and Esmeraldas.

- Mexico – widely used in the countryside of the state of Chiapas by indigenous populations and becoming rare among the same groups in the state of Tabasco.[25]

- Panama – in the west along the border with Costa Rica.

- Peru – in some areas in both the Northern and Southern ends of the country.

- Puerto Rico – At the eastern end of the island in Fajardo.[26]

- The Philippines – among Chavacano speakers in Mindanao and Luzon,[10][11] but otherwise absent in standard Spanish.[12]

- Spain – in La Gomera island, in The Canaries, often used alongside tú.

- The United States – Found among speakers with origins in countries where voseo is predominant—for instance, among Honduran Americans.[24] In other circumstances, tú is used by default.

- Venezuela – in the northwest (primarily in Zulia State).

Countries where voseo is virtually absent

[edit]In the following countries, voseo has disappeared completely among the native population:

- Dominican Republic

- Peninsular Spain

Synchronic analysis of Chilean and River Plate verbal voseo

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (December 2024) |

The traditional assumption that the Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms are derived from those corresponding to vosotros has been challenged as synchronically inadequate in a 2014 article,[16] on the grounds that it requires at least six different rules, including three monophthongization processes that lacks phonological motivation. Alternatively, the article argues that the Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms are synchronically derived from underlying representations that coincide with those corresponding to the non-honorific second person singular tú. In both Chilean and Rioplatense Spanish, the voseo form assigns stress to the syllable following the verb's root, or its infinitive in the case of the future and conditional conjugations. This alone derives all the Rioplatense voseo verb conjugations, in all tenses. Chilean verb forms also undergo rules of semi-vocalization, vowel raising, and aspiration. In semi-vocalization, /s/ becomes the semivowel /j/ when after /a, o/; thus, -ás becomes -ái, and sos becomes soi 'you are'. The vowel raising rule turns stressed /e/ into /i/, so bebés becomes bebís. Aspiration, the norm in both Chilean and Rioplatense Spanish, means that syllable or word-final /s/ becomes pronounced like an [h].[16]

The proposed theory requires the use of only one special rule in the case of Chilean voseo. This rule plus other rules that are independently justified in the language make it possible to synchronically derive all the Chilean and River Plate voseo verb forms in a straightforward manner. The article additionally solves the problem posed by the alternate verbal forms of Chilean voseo like the future indicative (e.g. bailaríh or bailarái 'you will dance'), the present indicative forms of haber (habíh and hai 'you have'), and the present indicative of ser (soi, eríh and eréi 'you are'), without resorting to any ad hoc rules. All these different verb forms would come from different underlying representations. The future forms bailarái and bailaríh come from underlying /bailaˈɾas/ and /bailaˈɾes/, the latter related to the historical future form -és, which was documented in Chile in the 17th century. Habíh and hai come from /ˈabes/ and /as/, while soi and eríh come from /sos/ and /ˈeɾes/. The form erei also comes from /ˈeɾes/, with additional semi-vocalization. The theoretical framework of the article is that of classic generative phonology.[16]

Attitudes

[edit]In some countries, the pronoun vos is used with family and friends (T-form), like tú in other varieties of Spanish, and contrasts with the respectful usted (V-form used with third person) which is used with strangers, elderly, and people of higher socioeconomic status; appropriate usage varies by dialect. In Central America, vos can be used among those considered equals, while usted maintains its respectful usage. In Ladino, the pronoun usted is completely absent, so the use of vos with strangers and elders is the standard.

Voseo was long considered a backward or uneducated usage by prescriptivist grammarians. Many Central American intellectuals, themselves from voseante nations, have condemned the usage of vos in the past.[24] With the changing mentalities in the Hispanic world, and with the development of descriptive as opposed to prescriptive linguistics, it has become simply a local variant of Spanish. In some places it has become symbolically important and is pointed to with pride as a local defining characteristic.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Miranda, Stewart (1999). The Spanish Language Today. Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 0-415-14258-X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Real Academia Española. "voseo | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ "vos". Real Academia Española. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ Borrini, Alberto (24 February 1998). "Publicidad & Marketing. ¿Por qué usan el tuteo los avisos?". La Nación. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Gassó, María José (2009). "El voseo rioplatense en la clase de español" (PDF). Instituto Cervantes Belo Horizonte. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ Díaz Collazos, Ana María. Desarrollo sociolingüístico del voseo en la región andina de Colombia (1555–1976).

- ^ Bruquetas, Francisco (2015). Advanced Spanish. Bruquetas Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 9780578104355.

- ^ Del Pueyo, Raymundo (1792). A New Spanish Grammar, or the Elements of the Spanish Language. London: F. Wingrave. 159.

- ^ Luizete Guimarães Barros. 1990. Lengua y nación en la Gramática de Bello. Anuario brasileño de estudios hispánicos.

- ^ a b De Castro, Gefilloyd L. (2018). "The role of second person pronouns in expressing social behavior: An undocumented case in Zamboanga Chavacano". Philippine Journal of Linguistics. 49: 26–40. ISSN 0048-3796. Retrieved April 4, 2023 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b Herrera, Jerome (December 17, 2021). "Differences and Similarities Among the Chavacano Languages in the Philippines". La Jornada Filipina. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Quilis, Antonio; Casado-Fresnillo, Celia (2008). La lengua española en Filipinas: historia, situación actual, el chabacano, antología de textos [The Spanish Language in the Philippines: History, Current Situation, Chavacano, Anthology of Texts]. Madrid: Spanish National Research Council. p. 117. ISBN 978-84-00-08635-0.

- ^ a b c d e (in Spanish) Lapesa Melgar, Rafael. 1970. "Las formas verbales de segunda persona y los orígenes del voseo", in: Carlos H. Magis (ed.), Actas del III Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas (México, D.F., 26–31 Aug 1968). México: Colegio de México, 519–531.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) García de Diego, Vicente. [1951] 1981. Gramática histórica española. (3rd edition; 1st edition 1951, 2nd edition 1961, 3rd edition 1970, 1st reprint 1981.) Madrid: Gredos, 227–229.

- ^ -ides did not produce -íes because -iés and íes were already in use as Imperfect forms, cf. García de Diego ([1951] 1981: 228) and Lapesa (1970: 526).

- ^ a b c d e Baquero Velásquez, Julia M.; Westphal Montt, Germán F. (16 July 2014). "Un análisis sincrónico del voseo verbal chileno y rioplatense" (PDF). Forma y Función (in Spanish). 27 (2): 11–40. doi:10.15446/fyf.v27n2.47558.

- ^ "ir, irse | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas | RAE - ASALE". 22 July 2024.

- ^ "voseo | Diccionario panhispánico de dudas | RAE - ASALE". 22 July 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Mary (2016). "Epistemicity in voseo and tuteo negative commands in Argentinian Spanish". Journal of Pragmatics. 97: 37–54. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2016.02.003.

- ^ Moyna, María Irene & Rivera-Mills, Susana (2016). Forms of Address in Spanish across the Americas. John Benjamins. pp. 127–148. ISBN 9789027258090.

- ^ See for example in Real Academia Española Dictionary, mentir or preocupar, where mentís and preocupás are present, but mintás and preocupés are missing.

- ^ Maria Irene Moyna, Susana Rivera-Mills (2016). Forms of Address in the Spanish of the Americas. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 243–263. ISBN 978-90-272-6700-9.

- ^ Solano Rojas, Yamileth (1995). "Las formas pronominales: Vos – tu – usted en Costa Rica, análisis de una muestra". Revista Pensamiento Actual (in Spanish). 1 (1): 42–57.

- ^ a b c John M. Lipski. "El español que se habla en El Salvador y su importancia para la dialectología hispanoamericana" (PDF) (in Spanish).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Davis, Jack Emory (1971). "The Spanish of Mexico: An Annotated Bibliography for 1940–69". Hispania. 54: 624–656. doi:10.2307/337708. ISSN 0018-2133. JSTOR 337708.

- ^ Moreno de Alba, José G. (2001). El español en América (in Spanish) (3rd ed.). Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 232. ISBN 9681663934.

Sources

[edit]- (in Spanish) Díaz Collazos, Ana María. Desarrollo sociolingüístico del voseo en la región andina de Colombia (1555–1976)

- (in Spanish) El voseo at Spanish Wikibooks

- (in French) Le Voseo

- (in Spanish) Voseo Spanish Site dedicated to teaching Argentine Voseo usage

- (in Spanish) Carricaburo. Norma Beatriz (2003). El voseo en la historia y en la lengua de hoy – Las fórmulas de tratamiento en el español actual Archived 2016-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish) Hotta. Hideo (2000). La estandarización y el regionalismo en el voseo del español argentino

- (in Spanish) Roca, Luis Alberto (2007). Breve historia del habla cruceña y su mestizaje

- (in Spanish) Rosenblat, Ángel (2000). El castellano en Venezuela

- (in Spanish) Toursinov, Antón (2005). Formas pronominales de tratamiento en el español actual de Guatemala

Voseo

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Forms

Voseo is a pronominal and verbal phenomenon in the Spanish language characterized by the use of the second-person singular pronoun vos to address one person informally, frequently accompanied by verb conjugations adapted from second-person plural forms. This usage contrasts with the standard European Spanish reliance on tú for informal singular address.[4][2] Within voseo, two primary variants exist: pronominal voseo, which employs vos alongside the standard tú verb conjugations, and full voseo (also known as verbal voseo), which pairs vos with modified verb forms typically derived from the plural vosotros. For instance, in pronominal voseo, one might say Vos hablas (you speak), using the singular form, whereas full voseo could yield Vos habláis or regionally adapted forms like Vos hablás. A classic example of full voseo appears in Argentine Spanish as Vos sos (you are), contrasting with the standard Tú eres.[2][1] The pronoun vos derives etymologically from the Latin vōs, the nominative form of the second-person plural pronoun, which over time shifted in medieval Spanish to serve as a singular form of respect and familiarity before evolving into its current informal role in various dialects.[1][4] Voseo typically functions in contexts of intimacy, camaraderie, or regional custom, marking social closeness or informality among speakers.[5]Comparison with Tuteo and Ustedeo

Tuteo is the use of the second-person singular pronoun tú along with its corresponding verb conjugations to address an individual in informal, familiar situations, such as among friends, family, or peers. This form emphasizes intimacy and equality in social interactions.[6] Ustedeo, by contrast, employs the pronoun usted—derived historically from the polite expression vuestra merced (your mercy)—paired with third-person singular verb forms to denote formality, respect, or social distance.[6] It is the standard choice for addressing superiors, strangers, or in professional contexts throughout the Spanish-speaking world.[7] Voseo functions similarly to tuteo as an informal address system, signaling familiarity and closeness, but it replaces tú with vos and predominates in specific regional varieties, particularly in parts of Latin America.[6] While tuteo and voseo both convey solidarity among equals, the selection between them reflects dialectal preferences rather than stark functional differences; for example, in Argentina, voseo is routinely used with peers and family to foster rapport across social classes.[8] Ustedeo, however, remains distinctly polite and hierarchical, applied universally to authority figures or in deferential scenarios, irrespective of regional norms—such as when subordinates address employers.[7] Voseo, like tuteo, pertains exclusively to singular address and does not extend to plurals. In Spain, the informal second-person plural is vosotros, which uses dedicated second-person plural conjugations, whereas ustedes serves as the formal plural equivalent.[9] In the Americas, ustedes has generalized to cover both formal and informal plural contexts, typically with third-person plural verb forms, creating an asymmetry where singular options (tuteo, voseo, ustedeo) vary more than their plural counterparts.[6]Historical Development

Origins and Early Usage

The pronoun vos in Spanish derives from the Latin vōs, which in Classical Latin served exclusively as the second-person plural form of "you," without any inherent distinction for deference or singular/plural formality in address.[10] In Vulgar Latin and early Romance languages, around 200–500 AD, vos began to extend beyond its plural usage, adopting a reverential connotation for singular address, particularly among nobility and royalty, as a marker of respect.[6] This shift marked the initial development of voseo as a formal address form, diverging from the more neutral tu for informal singular use. During the Old Spanish period (8th–15th centuries), vos functioned both as the plural "you" and as a singular formal pronoun, embodying what is known as reverential voseo.[10] This dual role is evident in early literary texts, such as the Cantar de Mio Cid (c. 1200), where vos appears in respectful singular contexts alongside plural agreements, reflecting its status as a polite form of address across social strata.[6] Historical documents from this era, including royal decrees, further illustrate vos's prevalence in formal interactions, underscoring its role in hierarchical communication.[10] The introduction of tú as an informal singular pronoun around the 14th–15th centuries began to reshape the pronominal system, positioning tú for intimate or subordinate relationships while vos retained its formal singular application.[6] By the 16th century, however, vos started declining in formal Peninsular Spanish contexts due to the rise of alternative respectful forms like vuestra merced (later contracted to usted), leading to its gradual pejoration and restriction primarily to plural usage as vosotros.[10] Literary works and official writings up to this period, such as those in the Libro del Caballero Zifar (early 14th century), capture the transitional dynamics of vos before its formal diminishment in Spain.[6]Spread to the Americas

During the 16th-century Spanish colonization of the Americas, the pronoun vos was transported by settlers, a significant portion of whom originated from southern regions like Andalusia and Extremadura, where it served both reverential and informal functions. In the colonial context, vos initially retained its reverential tone among elites but rapidly evolved into an informal address form due to the relative social leveling among colonists, indigenous populations, and enslaved Africans, which diminished rigid hierarchical distinctions present in the metropole. This early adaptation marked the beginning of voseo's divergence from European Spanish norms, as the pronoun embedded itself in the emerging creole varieties across the New World.[1][11] By the 17th and 18th centuries, voseo declined sharply in Spain, where tú assumed dominance for informal address and usted formalized respect, rendering vos largely obsolete except in archaic or regional pockets. In contrast, the Americas preserved voseo, bolstered by the linguistic influences of Andalusian and Extremaduran dialects prevalent among early migrants, which featured alternating vos and tú usage. Geographic isolation in peripheral colonies, such as those in the River Plate basin and Central America, further insulated voseo from Peninsular shifts, allowing it to thrive amid diverse substrates including indigenous languages and African linguistic elements that facilitated its informal entrenchment.[1][12] In the 19th century, voseo solidified as the predominant informal second-person singular in the River Plate region (encompassing modern Argentina and Uruguay) and Central America, where it became a marker of everyday speech influenced by ongoing indigenous and African substrates that shaped phonetic and syntactic integrations. European immigration waves and political figures, such as Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina (1829–1852), reinforced its cultural prestige, positioning voseo as a symbol of local identity. The independence movements of the 1810s and 1820s, which dismantled colonial structures across Latin America, amplified this trend by empowering regional elites to codify vernacular forms like voseo in emerging national literatures and discourses, thereby tying it to postcolonial self-definition. Efforts by linguistic authorities, including Andrés Bello's 1847 Gramática in Chile—which advocated alignment with Peninsular tuteo—attempted to promote standardized forms but ultimately failed to eradicate voseo.[12][11] Early 20th-century interventions by the Real Academia Española to promote standardized forms also overlooked the deep-rooted regional variations and social functions of voseo, allowing it to persist and even expand in informal domains across its strongholds.[12][2]Grammatical Features

Types of Voseo

Voseo manifests in several internal varieties, primarily distinguished by whether it affects the pronoun, the verb conjugation, or both. These categories—pronominal voseo, verbal voseo, and mixed or hybrid voseo—reflect different degrees of integration between the second-person singular pronoun vos and its associated morphological forms. Linguists classify these based on the extent to which archaic plural elements influence the singular address system.[13] Pronominal voseo involves the use of the pronoun vos paired with standard verb conjugations typically associated with tú (second-person singular) or even third-person singular forms, without altering the verbal morphology. For instance, in certain Central American varieties, speakers say Vos tienes ("You have"), where tienes follows the tú paradigm. This type emphasizes the replacement of the pronoun while preserving familiar verbal endings, often resulting in a straightforward substitution that maintains syntactic simplicity.[12] Verbal voseo, in contrast, features specialized verb forms derived from the historical second-person plural (vosotros), applied to the singular vos, while the pronoun itself may or may not be explicitly used. These forms arise etymologically from archaic plural influences, such as the Old Spanish vós (plural "you"), where plural verb endings like -áis were adapted and simplified for singular informal address, evolving into endings like -ás through diphthong reduction and analogy. A representative example in the present indicative is hablás (from habláis), as in Vos hablás español ("You speak Spanish"). This type prioritizes morphological innovation in the verb to signal familiarity.[1][13] Mixed or hybrid voseo combines elements of the pronominal and verbal types, often inconsistently across grammatical moods, creating layered forms that blend paradigms. For example, the indicative might use a verbal voseo form like Vos tenés ("You have"), drawing from plural -éis > -és, while the subjunctive retains tú conjugations, such as que vos tengas ("that you have"). This hybridity is evident in imperatives, where the tú form habla ("speak") shifts to accented hablá for vos, stressing the final syllable to distinguish it from the third-person singular. Such combinations allow for flexibility but can lead to regional inconsistencies in mood alignment.[12][13]Conjugation Patterns

Voseo conjugation patterns vary regionally but generally follow systematic rules distinct from tuteo, primarily affecting the present indicative, imperative, and present subjunctive moods, while other tenses often align with tú forms. In the most widespread verbal voseo (as in Rioplatense and Central American varieties), regular verbs in the present indicative take endings with final stress: -ás for -ar verbs (e.g., hablás 'you speak'), -és for -er verbs (e.g., comés 'you eat'), and -ís for -ir verbs (e.g., vivís 'you live'). Irregular verbs adapt similarly, such as tenés for tener ('you have') or sos for ser ('you are'), though some like ir retain the tú form vas ('you go'). In Chilean voseo, the pattern diverges for -ar verbs with -ái (e.g., llegái 'you arrive'), while -er/-ir follow -ís (e.g., comís, vivís), and irregularities like vas for ir persist.[13][14] The affirmative imperative in voseo derives from the infinitive minus -r, with stress on the final syllable: hablá ('speak!'), comé ('eat!'), viví ('live!'). Negative imperatives typically use the present subjunctive form with vos (e.g., no hablés 'don't speak'), aligning with tú subjunctive patterns but sometimes featuring voseo-specific stress. For other tenses, voseo largely mirrors tú conjugations: the imperfect indicative uses -abas/-ías (e.g., hablabas 'you were speaking'), preterite follows -aste/-iste (e.g., hablaste 'you spoke'), and future/conditional forms are rare but adopt tú endings like -ás/-ías (e.g., hablarás 'you will speak') or plural-like patterns in some contexts.[15][16] In the present subjunctive, voseo often employs the same forms as tú (e.g., hables 'that you speak', comas 'that you eat', vivas 'that you live'), especially in Rioplatense varieties where vos pairs with tuteo endings. However, Central American and some Andean regions (e.g., Cali, Colombia) feature specialized endings with final stress: -és for -ar (hablés), -ás for -er (comás), and -ás for -ir (vivás). These patterns emphasize voseo's role in informal address, with stress shifts distinguishing it from standard tuteo.[15][16][14] The following table illustrates conjugation patterns for regular verbs in the present indicative, affirmative imperative, and present subjunctive, based on predominant Rioplatense and Central American voseo (noting subjunctive variations):| Tense/Mood | -ar (hablar) | -er (comer) | -ir (vivir) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present Indicative | hablás | comés | vivís |

| Affirmative Imperative | hablá | comé | viví |

| Present Subjunctive (tú-like, e.g., Rioplatense) | hables | comas | vivas |

| Present Subjunctive (voseo-specific, e.g., Central American) | hablés | comás | vivás |