Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Christopher Clavius

View on Wikipedia

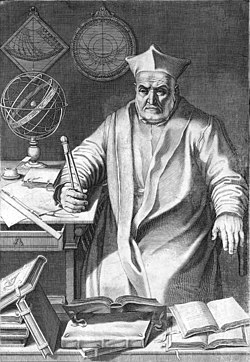

Christopher Clavius, SJ (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612[1]) was a Jesuit German mathematician and physicist, head of mathematicians at the Collegio Romano, and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar invented by Aloysius Lilius, that is known as the Gregorian calendar. Clavius would later write defences and an explanation of the reformed calendar, including an emphatic acknowledgement of Lilius' work. In his last years, he was probably the most respected astronomer in Europe and his textbooks were used for astronomical education for over fifty years in and even out of Europe.[2]

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Little is known about Christopher Clavius' early life, with the only certain fact being that he was born in Bamberg in either 1538 or 1537.[3] His given name is not known to any great degree of certainty—it is thought by scholars to have perhaps been Christoph Clau or Klau. There are also some who think that his taken name, Clavius, may be a Latinization of his original German name, suggesting that his name may have been Schlüssel (German for 'key', which is clavis in Latin).

Clavius joined the Jesuit order in 1555. He attended the University of Coimbra in Portugal, where it is possible that he had some kind of contact with the famous mathematician Pedro Nunes (Petrus Nonius). Following this he went to Italy and studied theology at the Jesuit Collegio Romano in Rome. He was ordained in 1564, and 15 years later was assigned to compute the basis for a reformed calendar that would stop the slow process in which the Church's holidays were drifting relative to the seasons of the year. Using the Prussian Tables of Erasmus Reinhold and building on the work of Aloysius Lilius, he proposed a calendar reform that was adopted in 1582 in Catholic countries by order of Pope Gregory XIII and is now the Gregorian calendar used worldwide.

Within the Jesuit order, Clavius was almost single-handedly responsible for the adoption of a rigorous mathematics curriculum in an age where mathematics was often ridiculed by philosophers as well as fellow Jesuits like Benito Pereira.[4] In logic, Clavius' Law (inferring of the truth of a proposition from the inconsistency of its negation) is named after him.

He used the decimal point in the goniometric tables of his astrolabium in 1593 and he was one of the first who used it in this way in the West.[5][6]

Astronomy

[edit]

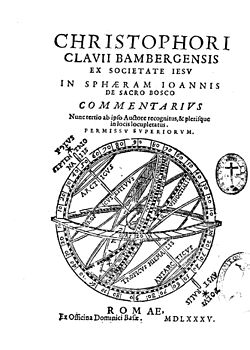

Clavius wrote a commentary on the most important astronomical textbook of the late Middle Ages, De Sphaera of Johannes de Sacrobosco. The commentary by Clavius was one of the most influential astronomy textbooks of its time and had at least 16 editions between 1570 and 1618, with Clavius himself revising the text seven times and in each case greatly expanding it.[7] In the 1585 edition of his aforementioned commentary he located (independently of Tycho Brahe) the nova from 1572 in the fixed stars sphere (in the constellation of Cassiopeia) and found that the position of the nova was exactly the same for all observers. That meant that it had to be beyond the Moon, and the doctrine that the heavens could not change was proven false.[8]

As an astronomer Clavius adhered strictly to the geocentric model of the Solar System, in which all the heavens rotate about the Earth. Though he opposed the heliocentric model of Copernicus, he recognized problems with the Ptolemaic model. He was treated with great respect by Galileo, who visited him in 1611 and discussed the new observations being made with the telescope; Clavius had by that time accepted the new discoveries as genuine,[9] though he retained doubts about the reality of the mountains on the Moon and said he could not see the four Jupiter's satellites through the telescope.[10] Later, a large crater on the Moon was named in his honor.

Collegio Romano

[edit]During his time at Collegio Romano Clavius served as the head of the mathematicians, a public professor of mathematics, and as the Director of Advanced Instruction and Research at the Academy of Mathematics until 1610 in an official capacity and for two more years until 1612 in an informal role.[11] The Academy existed in an informal capacity for many years before Clavius' arrival in Rome in 1561. However, in 1580 in his document titled Ordo servandus in addiscendis disciplinis mathematicis, Clavius described a detailed curriculum for mathematics to have the College officially recognize the Academy.[11]

The curriculum he proposed contained three different curricula aiming to educate new Jesuits in mathematics. The curriculum contained three different courses: one year, a two-year, and a three-year. The course material to be covered were optics, statics, astronomy, and acoustics,[11] emphasizing mathematics.

His request was eventually denied, but nonetheless he was given the title of Professor of Mathematics. Clavius made another attempt in 1586 to establish the Academy as an official course at the Collegio Romano, but there was opposition from the philosophers at the College. The Academy remained an unofficial curriculum until 1593 or 1594.

Upon its eventual founding, the Academy required nomination by the Professor of Mathematics for admission. Clavius taught the advanced course within the Academy, but little is known about his specific teachings and work as a professor during his time at the College. The exact number of students that Clavius taught is unclear, but in a letter from Christoph Grienberger to Clavius in 1595, it is stated that at that time, Clavius had around ten students.[11] The exact structure of the courses and how they were taught is unclear. There has been no evidence to show whether the students he taught shared classes or the specific material he chose to cover. The purpose for founding the Academy was to train technical specialists,[11] to expand the pedagogical corps to support the growing need for professors, as the number of colleges at the time was rapidly increasing,[11] as well as the training of missionaries in order to support their efforts in remote places.[11] With the purpose of the Academy clear, most of what Clavius and his students did in the Academy is unknown. This lack of detailed information has led to most of what Clavius did during his years at the College falling into obscurity.

Clavius and Galileo Galilei often shared correspondence during his time at the College, discussing proofs and theories. It is likely that while running the Academy, he was also writing to Galileo and sharing his notes from the College's logic course to help Galileo in his endeavors to be able to adequately explain and demonstrate his ideas to others, which is something Galileo had struggled with in the past, specifically when trying to convince Clavius of his methods.[12]

Following his death in 1612, informal courses in the Academy continued at the College. However, due to the lack of mention of mathematicians in the College's catalog after 1615, it appears the Academy's official recognition by the Collegio Romano ended soon after Christopher Clavius's death.[11]

Selected works

[edit]

- Commentary on Euclid: Euclidis Elementorum Libri XV, Rome 1574 [1]; (Cologne, 1591: [2] / [3])

- Gnomonices libri octo. 1581 [treatise of gnomonics]

- Fabrica et usus instrumenti ad horologiorum descriptionem peropportuni (in Latin). Roma: Bartolomeo Grassi. 1586.

- Novi calendarii romani apologia. Rome, 1588

- Astrolabium. Rome, 1593

- Horologiorum nova descriptio (in Latin). Roma: Luigi Zanetti. 1599.

- Romani calendarii a Gregorio XIII P.M. restituti explicatio. Rome, 1603 (An explanation of the Gregorian calendar)

- Romani calendarii a Gregorio XIII P.M. restituti explicatio. (European Cultural Heritage Online)

- Romani calendarii a Gregorio XIII P.M. restituti explicatio. (University of Notre Dame)

- Refutatio cyclometriae Iosephi Scaligeri. Mainz, 1609

- Elementorum Libri XV. Cologne, 1627 (Published online by the Sächsischen Landesbibliothek - Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden)

- Clavius, Christoph (1992). Corrispondenza Edizione critica a cura di Ugo Baldini e Pier Daniele Napolitani. Pisa: Università di Pisa – Dipartimento di Matematica. (Critical edition of his correspondence)

Clavius' complete mathematical works (5 volumes, Mainz, 1611–1612) are available online .

See also

[edit]

- Asteroid 20237 Clavius

- Clavius (crater), a lunar crater named after Clavius

- Clavius Base, located in Clavius crater, in both the novel and film versions of 2001: A Space Odyssey

- Aloysius Lilius

- Computus

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Bracket (mathematics)

References

[edit]- ^ ENCYCLOPEDIA.COM Clavius, Christoph

- ^ "The books of Clavius were translated into Chinese, by one of his students Matteo Ricci "Li Madou" (1552-1610), and his influence for the development of science in China was crucial." Costantino Sigismondi, Christopher Clavius astronomer and mathematician

- ^ The exact year is somewhat unknown and depends on when one assumes a new year begins.

- ^ Amir Alexander (2014). Infinitesimal: How a Dangerous Mathematical Theory Shaped the Modern World. Scientific American / Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0374176815., p. 69

- ^ Apparently Francesco Pellos used the decimal point in his Compendio del Abaco already around 1492 but was much less known than Clavius. Jekuthiel Ginsburg, "On the early history of the decimal point", American Mathematical Monthly 35 (1928) 347–349.

- ^ "Christopher Clavius", School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews

- ^ James M. Lattis, article Clavius, in New Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Volume 2.

- ^ Clavius himself acknowledged this in his 1585 commentary: «If it is true [that the nova is a new star] then Aristotle's followers ought to consider how they can defend his opinion about the matter in the heavens. For perhaps it should be said that the heavens are not made of a fifth element but changeable bodies - albeit less corruptible that the matter here on earth… Whatever it finally turns out to be (and I do not insert my opinion into such matters) it is enough for me at present that the star we are talking about is located in the sphere of the fixed stars.» Lattis, James M. (1994). Between Copernicus and Galileo: Christoph Clavius and the Collapse of Ptolemaic Cosmology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-226-46927-1.

- ^ Koestler, Arthur (1989) [1959 (by Hutchinson, London)]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Arkana, Penguin. p. 430 (Part V, Chapter 1: Triumph). ISBN 978-0-14-019246-9.

- ^ Koestler, Arthur (1989) [1959]. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. Penguin. p. 373 (Part IV, Chapter 8, The battle of the satelites).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Feingold, Mordechai, ed. (2002). Jesuit Science and the Republic of Letters. MIT Press. pp. 47–54. ISBN 9780262062343.

- ^ Wallace, William (1984). The Heritage of the Collegio Romano. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 281–291. ISBN 9780691612195.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Ralf Kern, Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit. Cologne, 2010. pp. 254 – 255.

- Lattis, James M. (1994). Between Copernicus and Galileo: Christoph Clavius and the Collapse of Ptolemaic Cosmology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-46927-1.

- Karl Christian Bruhns (1876). "Clavius, Christoph". Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 4. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. pp. 298–299.

- Edmondo Lamalle (1957). "Clavius, Christoph". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 3. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p. 279.

- Christoph Clavius, Corrispondenza, Edizione critica a cura di Ugo Baldini e Pier Daniele Napolitani, 7 volumes, Edizioni del Dipartimento di Matematica dell'Università di Pisa, Pisa, 1992

External links

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Christopher Clavius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Christopher Clavius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Christopher Clavius (1537-1612), The Galileo Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Christopher Clavius", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Materialsammlung zur Geschichte von Ingolstadt: Rita Haub: Christoph Clavius

- Cristoforo Clavio in the Historical Archives of the Pontifical Gregorian University

- Project Clavius On The Web. A Web platform for the works and literature of Christophorus Clavius, CNR-IIT, CNR-ILC, APUG

Christopher Clavius

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Christopher Clavius was born on 25 March 1538 in Bamberg, in the Franconian region of the Holy Roman Empire (now Germany).[5][6] Some sources suggest a birth year of 1537, but 1538 is more commonly accepted based on contemporary records.[3] Little is known about Clavius's family background or his original German name, which he later Latinized to "Clavius" (meaning "key"), possibly derived from a surname like "Clau" or "Schlüssel."[5] His family was of modest means and adhered to Catholicism in a region that remained a Catholic stronghold.[5] Bamberg, governed as a prince-bishopric, resisted the spread of the Protestant Reformation during the 16th century, maintaining its Roman Catholic identity amid surrounding Protestant pressures in the Holy Roman Empire.[5][7] This socio-political context likely shaped Clavius's early environment, with the local Catholic clergy and institutions providing initial exposure to humanities and religious education through schools in the city.[7] Around 1555, at the age of seventeen, Clavius left Bamberg for Rome, entering the Jesuit order as a novice—a pivotal step influenced by his religious vocation.[5][3]Jesuit Training and Studies

In 1555, at the age of seventeen, Christopher Clavius, born in Bamberg to a family of modest means that fostered his early religious inclinations, entered the Society of Jesus in Rome, beginning his novitiate and initial formation in the order's spiritual and intellectual disciplines.[5] This period of probationary training emphasized Jesuit vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, alongside rudimentary studies in humanities and rhetoric, laying the groundwork for his lifelong commitment to education and scholarship within the order.[8] From 1556 to 1560, Clavius was sent to the University of Coimbra in Portugal, where the Jesuits had established a college, to pursue formal studies in logic and philosophy as part of the standard Jesuit curriculum.[3] There, he received his initial exposure to mathematics amid prominent Portuguese scholars, possibly influenced by the works of the renowned cosmographer Pedro Nunes on navigation and geometry, which shaped his developing interest in quantitative sciences.[8] During his time there, Clavius observed a total solar eclipse on 21 August 1560, an event that solidified his interest in astronomy as his life's work.[3] These years focused on Aristotelian logic and natural philosophy, providing a rigorous foundation in deductive reasoning and the study of nature that would shape his later pedagogical approach.[8] In 1561, Clavius returned to Rome and transferred to the Collegio Romano to advance his studies in theology and higher mathematics, completing the philosophical and theological requirements for the Jesuit novitiate.[3] He was ordained as a priest in 1564, amid this intensive phase that immersed him in key intellectual traditions, including Aristotelian philosophy as the cornerstone of Jesuit natural philosophy, the foundational astronomical text De Sphaera by Johannes de Sacrobosco, and early encounters with emerging Copernican heliocentric ideas through contemporary debates.[8] These influences honed his ability to synthesize classical authorities with new observations, fostering a balanced scholarly perspective.[9] Clavius achieved full membership in the Society of Jesus in 1575, following the completion of his tertianship—a final year of spiritual probation and reflection that solidified his role as a professed Jesuit.[5] This milestone marked the culmination of his formative training, equipping him with the philosophical depth and mathematical proficiency essential for his subsequent contributions to Jesuit education.[3]Career at the Collegio Romano

Professorship and Teaching

In 1564, upon his ordination as a Jesuit priest, Christopher Clavius began his tenure as professor of mathematics at the Collegio Romano in Rome, a role he maintained until his death in 1612, interrupted only by brief absences, including a period in Naples around 1596 and a visit to Spain in 1597.[5] His prior studies at the same institution from 1555 onward had equipped him with a deep familiarity with the Jesuit educational environment, preparing him to shape mathematical instruction there.[5] Clavius's pedagogical influence grew through his advocacy for a structured mathematics program. In 1580, he proposed a comprehensive curriculum for Jesuit colleges that integrated pure mathematics—such as arithmetic and geometry—with applied disciplines like astronomy and optics, aiming to elevate mathematics as a foundational tool for intellectual and missionary pursuits.[8] Although this ambitious plan encountered resistance from Aristotelian-leaning scholars who viewed mathematics as subordinate to philosophy and faced initial rejection in official Jesuit deliberations, Clavius implemented it unofficially via private study groups at the Collegio Romano by 1593–1594.[8] By 1595, these efforts had resulted in the training of approximately 8 to 10 advanced students, emphasizing both theoretical principles and practical applications to prepare them as future missionaries, scholars, and educators in remote regions.[8] Clavius's methods centered on lectures that combined rigorous logical exposition with visual aids, including diagrams and instrument-based demonstrations to illustrate concepts in astronomy and geometry.[8] He placed particular stress on Euclidean foundations, using step-by-step proofs and syllogistic reasoning to build conceptual clarity, often drawing on his own commentaries on Euclid's Elements to guide students from basic axioms to advanced theorems.[8] This approach not only fostered analytical skills but also underscored mathematics's harmony with theology and natural philosophy. His persistent efforts culminated in the 1599 Ratio Studiorum, the Jesuit order's official educational plan, which incorporated mathematics as an essential discipline for all students, mandating studies in Euclid for at least two months and promoting its role in illuminating divine order and empirical inquiry.[8] Through this integration, Clavius ensured that mathematical training became a cornerstone of Jesuit pedagogy, influencing generations of scholars across Europe and beyond.[8]Administrative and Other Roles

As the preeminent mathematician within the Society of Jesus, Christopher Clavius served as the head of the mathematics department at the Collegio Romano from 1564 until his death, overseeing the allocation of resources for mathematical studies and coordinating with Jesuit scholars across Europe and beyond to standardize curricula and share advancements in the field.[10][3] In this capacity, he managed the department's operations, including the procurement of instruments and texts essential for Jesuit education worldwide, ensuring the integration of mathematics into the order's broader intellectual mission.[8] Clavius maintained an extensive correspondence network, exchanging hundreds of letters with European mathematicians, astronomers, and Jesuit missionaries on topics such as calendar reform, instrument design, and mathematical problems, which facilitated the dissemination of knowledge within the order and influenced scholarly debates across the continent.[2][11] His letters, often preserved in Jesuit archives, connected the Collegio Romano to distant outposts, allowing him to advise on mathematical applications in missionary work and respond to queries from figures like Galileo Galilei.[12] In 1596, Clavius undertook a brief administrative sojourn at the Jesuit college in Naples, contributing to its organizational development during a period of expansion for the order's institutions in Italy.[5] The following year, in 1597, he traveled to Spain at the apparent request of the king, where he provided counsel on matters related to Jesuit colleges and educational initiatives.[13] In his later years, around 1611, Clavius's health began to decline, prompting him to reduce his administrative duties and delegate responsibilities to younger colleagues at the Collegio Romano while concentrating on revising his mathematical and astronomical treatises.[3] He continued this work until his death on 6 February 1612 in Rome, at the age of 73.[14]Mathematical Contributions

Arithmetic and Algebra

Clavius made significant contributions to practical arithmetic through his Epitome arithmeticae practicae, first published in 1583 and reissued in 1584, which served as a comprehensive textbook for computations essential to commerce, surveying, and astronomy.[15] The work emphasized efficient methods for basic operations, including shortcuts in division—such as galley division—and handling fractional remainders, demonstrated through examples like dividing large numbers while verifying results via casting out nines.[15] These techniques prioritized accessibility for non-specialists, reflecting Clavius's aim to integrate arithmetic into everyday and scientific applications.[5] In advancing fractional notation, Clavius used the decimal point in 1593 within a sine table in his Astrolabium. Recent research (as of 2024) has identified earlier uses dating to the 1440s, but his application remains a notable early instance in printed astronomical tables, though he did not explain or expand upon it systematically.[16] This innovation, later recognized as predating widespread adoption, built on his practical arithmetic framework and facilitated precise calculations in astronomy and other fields, influencing subsequent European mathematicians despite its initial limited application.[17] His arithmetic texts also covered methods for root extraction and proportion calculations, providing tools for solving problems in scaling and ratios that supported both commercial accounting and celestial computations.[18] Clavius's algebraic contributions appeared in his Algebra of 1608, a standalone treatise that systematized the subject for pedagogical use and covered equations up to the third degree.[18] The book introduced innovative symbolic notation, such as parentheses to denote aggregate quantities (e.g., enclosing terms to indicate summation), which enhanced clarity in algebraic expressions and distinguished it from earlier rhetorical styles.[18] While primarily focused on solving polynomial equations, it included brief applications to geometric problems, such as determining lengths via algebraic means, underscoring the interplay between algebra and spatial reasoning.[19] In number theory, Clavius engaged with foundational concepts through his extensive commentary on Euclid's Elements (1574 edition), where he elaborated on topics from Book VII, including divisibility and the nature of prime numbers.[20] His discussions clarified definitions, such as primes as numbers divisible only by themselves and unity, and extended to properties like perfect numbers—those equal to the sum of their proper divisors—aligning with Euclid's proofs while adapting them for Renaissance readers.[20] These expositions reinforced rigorous approaches to integer properties, bridging ancient theory with contemporary needs. Clavius's arithmetic and algebraic works exerted lasting influence on mathematics education, particularly in German-speaking regions through Jesuit colleges, where his textbooks standardized curricula and promoted practical computation over abstract theory.[18] Adopted by figures like René Descartes and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, they facilitated the dissemination of decimal-based methods and symbolic algebra, shaping early modern pedagogical practices across Europe.[5] His emphasis on decimal systems in later editions further encouraged their integration into instructional materials, contributing to the gradual shift toward modern notation in German mathematical training.[17]Geometry and Instruments

Clavius's commentary on Euclid's Elements, first published in 1574 and revised in subsequent editions, including 1589 and the 1612 Opera Mathematica, stands as a monumental contribution to Renaissance geometry, expanding the classical text with extensive annotations and original material to make it suitable for pedagogical use in Jesuit institutions. In later editions, such as 1589, Clavius included an alleged proof of the parallel postulate attributed to Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, along with his own reflections, while treating it as an axiom in his system, thereby highlighting ongoing debates about its axiomatic status.[21] Additionally, Clavius added propositions on circles, particularly in his treatment of Book III, where he elaborated on their properties with proofs grounded in Aristotelian logic, emphasizing syllogistic reasoning to bridge geometric demonstrations with philosophical principles.[8] These additions not only clarified Euclidean arguments but also integrated Aristotelian methodology, ensuring that geometric proofs aligned with the Jesuit emphasis on logical coherence and natural philosophy. A key aspect of Clavius's geometric work lay in his development of practical instruments for measurement, detailed in his Geometria practica (1604), which described the construction and use of quadrants, astrolabes, and sundials specifically for determining angles in surveying and navigation. Quadrants, for instance, were portrayed as versatile tools for measuring altitudes and elevations, with Clavius providing diagrams and calibration methods to achieve precision in field applications.[22] Astrolabes received similar treatment, with instructions on their assembly for angular computations, while sundials were adapted for both equatorial and vertical orientations to track solar positions accurately. These instruments exemplified Clavius's commitment to translating theoretical geometry into tangible devices, enhancing their utility in astronomy and engineering without relying on algebraic computations.[5] Clavius also advanced methods for dividing scales on instruments, introducing sophisticated techniques in Geometria practica that allowed for subdivisions of arbitrary fineness, such as iterative bisection and proportional division using geometric constructions. These approaches, rooted in Euclidean principles, enabled higher accuracy in measurements for surveying and instrument calibration, far surpassing contemporary mechanical limitations.[23] By applying such methods, practitioners could achieve resolutions down to minutes of arc, proving invaluable in both terrestrial mapping and celestial observations. Furthermore, Clavius integrated principles of perspective and optics into his geometric framework, particularly in sections of Geometria practica dealing with visual rays and vanishing points, which drew from Euclidean optics to explain projective properties. This synthesis influenced architectural designs by providing geometric tools for rendering facades and interiors with mathematical precision, allowing Jesuit architects to apply proportional scaling in church constructions.[8] Such integrations underscored geometry's role in bridging visual arts and science. In the Jesuit curricula, Clavius promoted geometry as a vital link between abstract theory and practical application, advocating its central place in the Ratio Studiorum (1599) to train students in both deductive reasoning and instrumental skills. Through his textbooks, he emphasized how Euclidean principles supported real-world tasks like fortification and timekeeping, fostering a holistic mathematical education that extended arithmetic notations briefly to aid geometric computations where needed.[8] This approach solidified geometry's status as an essential discipline in Jesuit pedagogy, influencing generations of scholars.Astronomical Contributions

Observations and Theories

Christopher Clavius conducted significant astronomical observations during his time at the Collegio Romano, beginning with solar eclipses that informed his refinements to prediction methods. In 1560, while studying in Coimbra, Portugal, he witnessed a total solar eclipse on August 21, describing the profound darkness that allowed stars to become visible and caused birds to fall from the sky, which he later detailed in his writings to validate eclipse timing calculations.[5] Seven years later, on April 9 in Rome, Clavius observed another solar eclipse, noting a narrow luminous circle around the Moon at maximum obscuration around midday, interpreted as possibly annular or involving the inner solar corona; his precise account of this event contributed to limiting estimates of Earth's rotational clock error (ΔT) and improving predictive accuracy for future eclipses.[5] In 1572, Clavius independently identified the supernova, then called a nova, in the constellation Cassiopeia, observing its position and brightness over months. By measuring the absence of parallax relative to fixed stars, he concluded the phenomenon originated beyond the Moon in the celestial sphere, challenging Aristotelian notions of an unchanging supralunar realm while upholding the geocentric framework as fundamentally intact.[5] This observation reinforced his commitment to empirical verification within traditional cosmology, distinguishing transient celestial events from permanent structures. Clavius's most influential astronomical work was his In sphaeram Ioannis de Sacro Bosco commentarius, first published in 1570 and revised through multiple editions until 1618, which systematically explained the Ptolemaic geocentric system with enhanced mathematical proofs to counter emerging challenges. In these texts, he critiqued Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric model as physically implausible and incompatible with scriptural and observational evidence, arguing it inverted natural hierarchies without sufficient justification.[24] He also updated discussions on comets, maintaining they were sublunar atmospheric phenomena rather than celestial bodies, based on their apparent parallax and irregular paths, thereby preserving the incorruptibility of the heavens.[25] Later in life, particularly in editions after 1588, Clavius acknowledged inaccuracies in pure Ptolemaic models, such as discrepancies in planetary retrograde motions, and expressed partial adherence to the Tychonic geo-heliocentric hybrid system as a viable alternative that reconciled observations with geocentrism without fully endorsing heliocentrism.[25] This shift reflected his pragmatic approach, recognizing the Tychonic framework's equivalence to Copernican predictions while avoiding theological conflicts. To support his theoretical work, Clavius employed self-constructed instruments, including quadrants and astrolabes, for precise measurements of planetary positions, which he integrated into ephemerides for verifying celestial tables and aiding practical astronomy.[5] These tools enhanced the accuracy of his geocentric models, emphasizing observation over speculation.Interactions with Contemporaries

Clavius maintained an extensive correspondence with Galileo Galilei beginning in 1587, following Galileo's first visit to Rome, where the two mathematicians discussed topics including hydrostatics, proofs in geometry, and astronomical theories.[26][27] Their exchange continued as a personal friendship, with Galileo seeking Clavius's endorsement for academic positions and sharing early ideas on mechanics.[13] In 1611, Galileo met Clavius again during another Roman visit, consulting him on telescopic observations amid growing debates in the scientific community.[28] Clavius responded to Galileo's Sidereus Nuncius (1610) by incorporating references to its discoveries in the 1611 edition of his Commentary on the Sphere of Sacrobosco, accepting the existence of Jupiter's moons as evidence of celestial bodies orbiting other than Earth and the resolution of the Milky Way into individual stars.[5] However, he expressed reservations about the reported phases of Venus, attributing them tentatively to observational errors or optical effects rather than endorsing a heliocentric model, due to his firm commitment to geocentric astronomy.[13][3] During his studies at the University of Coimbra from 1556 to 1560, Clavius interacted with Portuguese scholars, including the prominent mathematician Pedro Nunes, whose lectures and writings on instruments left a lasting influence on Clavius's later designs for astronomical tools like astrolabes and quadrants.[29] Clavius referenced Nunes over thirty times in his works, adapting concepts from Nunes's nonius scale to improve precision in measurement devices.[29] Clavius engaged in debates with Protestant mathematicians over the Gregorian calendar reform, defending the Catholic computations against critics like Michael Mästlin, who questioned the leap year rules and equinox adjustments in works such as his Novi calendarii romani apologia (1588).[13][30] These exchanges highlighted denominational tensions in chronology, with Clavius arguing for the reform's mathematical accuracy based on solar observations.[31] As a central figure in European astronomy, Clavius served as a bridge between Italian and German scholars, sharing his observations through letters with figures like Giovanni Antonio Magini in Italy and Tycho Brahe and Nicolaus Ursus in Germany, fostering collaborative verification of celestial events such as the 1572 supernova.[13][32] This network, involving over 110 correspondents, disseminated data across borders and reinforced Clavius's role in coordinating empirical astronomy.[13]Role in the Gregorian Calendar Reform

Commission Involvement

In 1579, Pope Gregory XIII appointed Christopher Clavius, then a prominent Jesuit mathematician at the Collegio Romano, to a special commission tasked with reforming the Julian calendar.[5] This group included key figures such as the physician and astronomer Antonio Lilio, brother of the late Aloysius Lilius who had proposed initial reform ideas, as well as other experts like the astronomer Ignazio Danti and cardinal Guglielmo Sirleto as chairman. The commission's formation addressed the Julian calendar's accumulating errors, which by 1582 had caused a drift of approximately 10 days, stemming from the Julian year's overestimate of the solar year by about 11 minutes and 14 seconds, leading to the vernal equinox shifting earlier and disrupting the calculation of Easter.[5] The commission convened in Rome from 1579 to 1582, conducting intensive deliberations that involved detailed computations of equinox timings based on astronomical observations and proposals for revised leap year rules to better align the calendar with the solar year.[5] Clavius served as the chief mathematician, meticulously verifying the mathematical foundations of the proposed changes and playing a central role in drafting the content for the papal bull Inter gravissimas, promulgated on February 24, 1582, which officially instituted the Gregorian calendar and mandated the omission of 10 days in October 1582.[33][3] The reform faced significant initial resistance across Europe, particularly in Protestant regions where suspicions of papal overreach fueled opposition; this delayed adoption in countries like England and Russia until centuries later.[5]Calculations and Defense

Clavius's calculations for the Gregorian calendar reform centered on correcting the Julian calendar's overestimate of the tropical year length, adopting a mean solar year of 365.2425 days. This value was derived from Aloysius Lilius's proposal, which Clavius refined using the Alfonsine tables' estimate of 365 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes, and 16 seconds for the tropical year. To achieve this mean length, the reform modified the leap year rule: years divisible by 4 remain leap years, except for century years, which are leap years only if divisible by 400. This effectively omits three leap days every 400 years, reducing the average year by 0.0075 days compared to the Julian 365.25 days and aligning the calendar with astronomical reality for about 3,500 years before accumulating a one-day error.[34] To determine the necessary adjustments, Clavius interpolated data from the Alfonsine tables, incorporated historical eclipse observations, and applied solar equation corrections to assess the vernal equinox's drift. The Julian calendar had accumulated a 10-day lag by 1582, shifting the equinox from March 21 to March 11. By analyzing eclipse timings and solar anomaly equations from medieval sources, Clavius confirmed this drift and calculated that restoring the equinox to March 21 required omitting 10 days in October 1582, with Thursday, October 4 (Julian), followed directly by Friday, October 15 (Gregorian). These computations emphasized mean solar time to ensure consistency across regions, avoiding reliance on variable true solar positions that lacked precise tables.[34] The reform's rules for ongoing accuracy included the immediate 10-day skip and the long-term omission of leap years in three century years per 400-year cycle (e.g., 1700, 1800, and 1900 as common years, but 2000 as a leap year). Clavius employed trigonometric tables for precise angular calculations in solar and lunar positions, alongside adjustments for mean solar time to standardize Easter computations relative to the equinox. This mathematical framework ensured the calendar's alignment with ecclesiastical needs while maintaining astronomical fidelity.[34] In Novi calendarii romani apologia (1588, expanded in later editions including the 1612 Opera mathematica), Clavius rigorously defended these calculations against critics, particularly mathematician Michael Maestlin, who questioned the use of Alfonsine tables over more modern ones and argued for different intercalation methods. Clavius refuted claims of excessive drift in the Julian calendar by demonstrating through eclipse data and table interpolations that the 10-day correction was empirically justified, countering assertions that the reform overcorrected the equinox position. He also addressed earlier erroneous estimates, such as those by Orontius Finaeus implying a longer year and minimal drift, by showing their incompatibility with observed solar motions and historical records. These defenses highlighted the reform's precision and practicality for uniform Christian observance.[35][36]Major Works

Commentaries and Textbooks

Clavius's commentaries on classical mathematical and astronomical texts formed the backbone of Jesuit education in the late sixteenth century, serving as widely adopted textbooks that blended rigorous scholarship with practical instruction. These works expanded upon foundational sources while incorporating contemporary observations and critiques, making complex subjects accessible to students at the Roman College and beyond.[8] His In Sphaeram Ioannis de Sacro Bosco Commentarius, first published in 1570, provided an extensive expansion on the medieval astronomer John of Sacrobosco's De Sphaera, a standard introductory text on celestial spheres. Clavius's commentary delved into theoretical astronomy, detailing the structure of the cosmos, spherical geometry, and the philosophical certainty of astronomical knowledge, while linking it to theology and natural philosophy. It incorporated his own eclipse observations, such as those from 1560 and 1567, and critiqued earlier interpretations to align with Ptolemaic models, though later editions subtly engaged with emerging heliocentric ideas. The work went through numerous editions, ensuring its status as a core textbook for over four decades.[8][6][5] In 1574, Clavius issued Euclidis elementorum libri XV, a comprehensive edition of Euclid's Elements that included the fifteen books of the original text plus a sixteenth on the comparison of regular solids. Preceded by a Propædeumatica section offering foundational explanations of geometry for beginners, the volume featured Clavius's detailed scholia drawing from classical authors like Theon of Smyrna and medieval commentators such as Campanus, alongside Renaissance figures like Federico Commandino. Appendices extended the discussion to mechanics, exploring applications like levers and pulleys, and to music, analyzing harmonic proportions through geometric ratios. This edition became the standard Euclidean textbook of the seventeenth century, praised for its thoroughness and integration of historical proofs.[8][37][2] Clavius's Epitome arithmeticae practicae, published in 1583, emerged as a practical guide to computation tailored for Jesuit students, covering arithmetic operations, proportions, and numerical methods essential for astronomy and surveying. The text emphasized everyday applications, from commercial accounting to astronomical tables, positioning arithmetic as a foundational skill for all scholars.[5][8] Among his other commentaries, Clavius engaged with Proclus's De Sphaera in the prefatory sections of his Euclid edition, translating and analyzing its geometric arguments on spheres to bridge ancient theory with practical astronomy. His arithmetic commentaries, including expansions on works by Jordanus de Nemore and Boethius, highlighted speculative number theory and its Jesuit applications in education and science. These efforts underscored Clavius's commitment to a unified curriculum.[8] Clavius's pedagogical approach in these texts prioritized clarity through straightforward Latin prose, profuse diagrams illustrating theorems and constructions—such as those for the Pythagorean theorem or regular polyhedra—and structured problem sets for classroom exercises. This method fostered both conceptual grasp and hands-on problem-solving, aligning with the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum and ensuring the commentaries' enduring use in European universities.[8][2]Opera Mathematica

Clavius's Opera Mathematica, published in Mainz between 1611 and 1612 by Antonius Hierat, represents his magnum opus, a five-volume compilation of his mathematical, astronomical, and related works assembled near the end of his life.[5][38] This extensive collection, exceeding 2,000 pages in total, synthesizes his contributions across pure and applied disciplines, including defenses of his astronomical positions.[39] The volumes are organized thematically: Volume I contains his commentary on Euclid's Elements and Theodosius's Sphaericorum libri III; Volume II covers works on geometry and algebra; Volume III includes his commentary on Sacrobosco's Sphaera (with eclipse observations) and a treatise on the astrolabe; Volume IV provides an account of sundial construction; Volume V focuses on the calendar reform.[5][40][38] In preparing the Opera Mathematica, Clavius undertook significant revisions to his earlier works, such as expanding proofs in his Euclid commentary, updating geographical descriptions, and adding new eclipse prediction tables based on recent observations, alongside enhanced illustrations of mathematical instruments like sundials and astrolabes.[38][40] The collection served as a comprehensive resource for Jesuit scholars, systematically addressing gaps in Renaissance mathematics by integrating theoretical foundations with practical applications suited to the order's educational needs, such as navigation and timekeeping for missionaries.[38][5] Posthumously, the Opera Mathematica was widely reprinted in editions such as those in Frankfurt (1654) and Venice (1721), remaining a standard reference for mathematics and astronomy in European universities and Jesuit colleges until the mid-18th century.[38][39]Legacy

Influence on Science and Education

Clavius's textbooks, particularly his commentary on Euclid's Elements published in 1574, served as foundational texts for mathematics education across Europe for over a century, standardizing the teaching of Euclidean geometry and astronomy. These works were widely adopted in Jesuit institutions and beyond, influencing prominent figures such as René Descartes, who drew upon Clavius's geometric and algebraic expositions during his early studies, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, whose algebraic developments echoed Clavius's innovations like the use of parentheses for grouping, and early Newtonians who relied on his astronomical commentaries for computational methods. By the mid-17th century, Clavius's texts had undergone multiple editions and translations, ensuring their role in shaping rigorous mathematical pedagogy that emphasized both theoretical proofs and practical applications.[5][41] In the realm of Jesuit education, Clavius played a pivotal role in formulating the Ratio Studiorum of 1599, which positioned mathematics as the "handmaid" to theology, integrating it into the core curriculum to train missionaries in practical sciences like astronomy and cartography for evangelization efforts. This framework elevated mathematics from a peripheral subject to a essential tool for understanding divine order, influencing the establishment of over 400 Jesuit colleges by 1626, where Clavius's textbooks were mandated. His emphasis on computation and observation fostered a scientific ethos within these institutions, contributing to the development of Jesuit observatories that prioritized empirical data collection, such as eclipse predictions and celestial mappings, thereby advancing the scientific method through verifiable calculations.[41][42] Clavius's promotion of mathematics extended to Germany, where his works were translated and adopted in Protestant universities, bridging confessional divides and standardizing mathematical instruction in institutions like those in Wittenberg and Helmstedt during the 17th century. This cross-denominational influence helped disseminate Euclidean and astronomical knowledge, preparing a generation of scholars for advancements in natural philosophy. Scientifically, Clavius provided a robust geocentric framework that underpinned Galileo Galilei's early astronomical investigations, as Galileo himself acknowledged the superiority of Clavius's Commentarius in Sphaeram over traditional texts. Furthermore, Clavius's calculations for the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582 were progressively adopted worldwide, culminating in Britain's implementation in 1752, which aligned global timekeeping and facilitated international scientific coordination.[41][43][44]Recognition and Modern Assessments

One of the earliest posthumous honors bestowed upon Clavius was the naming of a prominent lunar crater after him in 1651 by the Jesuit astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli, located at coordinates 58.4° S, 14.4° W on the Moon's southern highlands, symbolizing his enduring legacy in astronomy.[45][46] This large impact feature, measuring approximately 231 km in diameter, stands as a testament to Clavius's contributions to celestial observation and mathematical astronomy, as Riccioli's nomenclature drew from influential figures in the field.[47] In the 20th century, Clavius's work experienced a significant rediscovery through scholarly studies highlighting his pioneering use of the decimal point in astronomical tables published in 1593, predating common adoption and influencing later numerical notation.[5] Additionally, analyses confirmed the high accuracy of his calculations for the Gregorian calendar reform, which introduced an error of only one day every 3,300 years, far surpassing the Julian calendar's drift of one day every 128 years.[48] These reevaluations underscored Clavius's role in advancing precise computational methods during the Renaissance. Modern scholarly assessments portray Clavius as a conservative innovator who bridged medieval scholastic traditions with emerging modern science, integrating Aristotelian frameworks with rigorous mathematical analysis while defending Ptolemaic geocentrism against heliocentric challenges.[8] Although critiqued for his staunch adherence to a geocentric model, which prioritized physical realism in saving celestial phenomena over revolutionary paradigms, he is praised for his empiricism, as evidenced by his detailed eclipse observations that emphasized verifiable data over speculation.[49][50] Archival efforts have further recognized Clavius through the digitization of his extensive works, such as mathematical tables and commentaries available on platforms like e-rara.ch, facilitating global access to his original texts.[51] Contemporary papers, including those on arXiv, have analyzed his eclipse observations—for instance, the 1567 annular solar eclipse in Rome, which he described as a ring of light around the Moon, providing early insights into solar diameter variations and annular phenomena.[52] Clavius features prominently in historical accounts of the Gregorian calendar's development, where his computations and defenses are credited with ensuring its astronomical precision and widespread adoption.[3] He is also highlighted in studies of Jesuit contributions to science, exemplifying the order's synthesis of faith and empirical inquiry in the early modern era.[5] His educational influences, through reformed curricula at Jesuit institutions, extended into the Enlightenment, shaping pedagogical approaches to mathematics and astronomy.[18]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Galileo_Galilei_and_the_Roman_Curia/Chapter_1