Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Jesuits

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on the |

| Society of Jesus |

|---|

|

| History |

| Hierarchy |

| Spirituality |

| Works |

| Notable Jesuits |

The Society of Jesus (Latin: Societas Iesu; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits (/ˈdʒɛʒuɪts, ˈdʒɛzju-/ JEZH-oo-its, JEZ-ew-;[2] Latin: Iesuitae),[3] is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola and six companions, with the approval of Pope Paul III. The Society of Jesus is the largest religious order in the Catholic Church and has played a significant role in education, charity, humanitarian acts and global policies. The Society of Jesus is engaged in evangelization and apostolic ministry in 112 countries. Jesuits work in education, research, and cultural pursuits. They also conduct retreats, minister in hospitals and parishes, sponsor direct social and humanitarian works, and promote ecumenical dialogue.

The Society of Jesus is consecrated under the patronage of Madonna della Strada, a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and it is led by a superior general.[4][5] The headquarters of the society, its general curia, is in Rome.[6] The historic curia of Ignatius is now part of the Collegio del Gesù attached to the Church of the Gesù, the Jesuit mother church.

Members of the Society of Jesus make profession of "perpetual poverty, chastity, and obedience" and "promise a special obedience to the sovereign pontiff in regard to the missions." A Jesuit is expected to be totally available and obedient to his superiors, accepting orders to go anywhere in the world, even if required to live in extreme conditions. Ignatius, its leading founder, was a nobleman who had a military background. The opening lines of the founding document of the Society of Jesus accordingly declare that it was founded for "whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God,[a] to strive especially for the defense and propagation of the faith, and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine".[7] Jesuits are thus sometimes referred to colloquially as "God's soldiers",[8] "God's marines",[9] or "the Company".[10] The Society of Jesus participated in the Counter-Reformation and, later, in the implementation of the Second Vatican Council.

Jesuit missionaries established missions around the world from the 16th to the 18th century and had both successes and failures in Christianizing the native peoples. The Jesuits have always been controversial within the Catholic Church and have frequently clashed with secular governments and institutions. Beginning in 1759, the Catholic Church expelled Jesuits from most countries in Europe and from European colonies. Pope Clement XIV officially suppressed the order in 1773. In 1814, the Church lifted the suppression.

History

[edit]Foundation

[edit]

Ignatius of Loyola, a Basque nobleman from the Pyrenees area of northern Spain, founded the society after discerning his spiritual vocation while recovering from a wound sustained in the Battle of Pamplona.

On 15 August 1534, Ignatius of Loyola (born Íñigo López de Loyola), a Spaniard from the Basque city of Loyola, and six others mostly of Castilian origin, all students at the University of Paris,[11] met in Montmartre outside Paris, in a crypt beneath the church of Saint Denis, now Saint Pierre de Montmartre, to pronounce promises of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[12] Ignatius' six companions were: Francisco Xavier from Navarre (modern Spain), Alfonso Salmeron, Diego Laínez, Nicolás Bobadilla from Castile (modern Spain), Peter Faber from Savoy, and Simão Rodrigues from Portugal.[13]

The meeting is commemorated in the Martyrium of Saint Denis, Montmartre. They called themselves the Compañía de Jesús, and also Amigos en El Señor or "Friends in the Lord", because they felt "they were placed together by Christ." The name "company" had echoes of the military (reflecting perhaps Ignatius' background as captain in the Spanish army) as well as of discipleship (the "companions" of Jesus). The Spanish "company" would be translated into Latin as societas like in socius, a partner or comrade. From this came Societas Iesu (S.J.), in English Society of Jesus, by which they would be known more widely.[14]

Religious orders established in the medieval era were named after particular men: Francis of Assisi (Franciscans); Domingo de Guzmán, later canonized as Saint Dominic (Dominicans); and Augustine of Hippo (Augustinians). Ignatius of Loyola and his followers appropriated the name of Jesus for their new order, provoking resentment by other orders who considered it presumptuous. The resentment was recorded by Jesuit José de Acosta of a conversation with the Archbishop of Santo Domingo.[15]

In the words of one historian: "The use of the name Jesus gave great offense. Both on the Continent and in England, it was denounced as blasphemous; petitions were sent to kings and to civil and ecclesiastical tribunals to have it changed; and even Pope Sixtus V had signed a Brief to do away with it." But nothing came of all the opposition; there were already congregations named after the Trinity and as "God's daughters".[16]

In 1537, the seven travelled to Italy to seek papal approval for their order. Pope Paul III gave them a commendation, and permitted them to be ordained priests. These initial steps led to the official founding in 1540.

They were ordained in Venice by the bishop of Arbe on 24 June. They devoted themselves to preaching and charitable work in Italy. The Italian War of 1536–1538 renewed between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Venice, the Pope, and the Ottoman Empire, had rendered any journey to Jerusalem impossible.

Again in 1540, they presented the project to Paul III. After months of dispute, a congregation of cardinals reported favourably upon the Constitution presented, and Paul III confirmed the order through the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae ("To the Government of the Church Militant"), on 27 September 1540. This is the founding document of the Society of Jesus as an official Catholic religious order. Ignatius was chosen as the first Superior General. Paul III's bull had limited the number of its members to sixty. This limitation was removed through the bull Exposcit debitum of Julius III in 1550.[17]

In 1543, Peter Canisius entered the company. Ignatius sent him to Messina, where he founded the first Jesuit college in Sicily.

Ignatius laid out his original vision for the new order in the "Formula of the Institute of the Society of Jesus",[18] which is "the fundamental charter of the order, of which all subsequent official documents were elaborations and to which they had to conform".[19] He ensured that his formula was contained in two papal bulls signed by Pope Paul III in 1540 and by Pope Julius III in 1550.[18] The formula expressed the nature, spirituality, community life, and apostolate of the new religious order. Its famous opening statement echoed Ignatius' military background:

Whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God beneath the banner of the Cross in our Society, which we desire to be designated by the Name of Jesus, and to serve the Lord alone and the Church, his spouse, under the Roman Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ on earth, should, after a solemn vow of perpetual chastity, poverty and obedience, keep what follows in mind. He is a member of a Society founded chiefly for this purpose: to strive especially for the defence and propagation of the faith and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine, by means of public preaching, lectures and any other ministration whatsoever of the Word of God, and further by means of retreats, the education of children and unlettered persons in Christianity, and the spiritual consolation of Christ's faithful through hearing confessions and administering the other sacraments. Moreover, he should show himself ready to reconcile the estranged, compassionately assist and serve those who are in prisons or hospitals, and indeed, to perform any other works of charity, according to what will seem expedient for the glory of God and the common good.[20]

In fulfilling the mission of the "Formula of the Institute of the Society", the first Jesuits concentrated on a few key activities. First, they founded schools throughout Europe. Jesuit teachers were trained in both classical studies and theology, and their schools reflected this. These schools taught with a balance of Aristotelian methods with mathematics.[21]

Second, they sent out missionaries across the globe to evangelize those peoples who had not yet heard the Gospel, founding missions in widely diverse regions such as modern-day Paraguay, Japan, Ontario, and Ethiopia. One of the original seven arrived in India already in 1541.[22] Finally, though not initially formed for the purpose, they aimed to stop Protestantism from spreading and to preserve communion with Rome and the pope. The zeal of the Jesuits overcame the movement toward Protestantism in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and southern Germany.

Ignatius wrote the Jesuit Constitutions, adopted in 1553, which created a centralised organization and stressed acceptance of any mission to which the pope might call them.[23][24][25] His main principle became the unofficial Jesuit motto: Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam ("For the greater glory of God"). This phrase is designed to reflect the idea that any work that is not evil can be meritorious for the spiritual life if it is performed with this intention, even things normally considered of little importance.[17]

The Society of Jesus is classified among institutes as an order of clerks regular, that is, a body of priests organized for apostolic work, and following a religious rule.

The term Jesuit (of 15th-century origin, meaning "one who used too frequently or appropriated the name of Jesus") was first applied to the society in reproach (1544–1552).[26] The term was never used by Ignatius of Loyola, but over time, members and friends of the society adopted the name with a positive meaning.[16]

While the order is limited to men, Joanna of Austria, Princess of Portugal, favored the order and she is reputed to have been admitted surreptitiously under a male pseudonym.[27]

Early works

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

The Jesuits were founded just before the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and ensuing Counter-Reformation that would introduce reforms within the Catholic Church, and so counter the Protestant Reformation throughout Catholic Europe.

Ignatius and the early Jesuits did recognize, though, that the hierarchical church was in dire need of reform. Some of their greatest struggles were against corruption, venality, and spiritual lassitude within the Catholic Church. Ignatius insisted on a high level of academic preparation for the clergy in contrast to the relatively poor education of much of the clergy of his time. The Jesuit vow against "ambitioning prelacies" can be seen as an effort to counteract another problem evidenced in the preceding century.

Ignatius and the Jesuits who followed him believed that the reform of the church had to begin with the conversion of an individual's heart. One of the main tools the Jesuits have used to bring about this conversion is the Ignatian retreat, called the Spiritual Exercises. During a four-week period of silence, individuals undergo a series of directed meditations on the purpose of life and contemplations on the life of Christ. They meet regularly with a spiritual director who guides their choice of exercises and helps them to develop a more discerning love for Christ.

The retreat follows a "Purgative-Illuminative-Unitive" pattern in the tradition of the spirituality of John Cassian and the Desert Fathers. Ignatius' innovation was to make this style of contemplative mysticism available to all people in active life. He used it as a means of rebuilding the spiritual life of the church. The Exercises became both the basis for the training of Jesuits and one of the essential ministries of the order: giving the exercises to others in what became known as "retreats".

The Jesuits' contributions to the late Renaissance were significant in their roles both as a missionary order and as the first religious order to operate colleges and universities as a principal and distinct ministry.[21] By the time of Ignatius' death in 1556, the Jesuits were already operating a network of 74 colleges on three continents. A precursor to liberal education, the Jesuit plan of studies incorporated the Classical teachings of Renaissance humanism into the Scholastic structure of Catholic thought.[21] This method of teaching was important in the context of the Scientific Revolution, as these universities were open to teaching new scientific and mathematical methodology. Further, many important thinkers of the Scientific Revolution were educated by Jesuit universities.[21]

In addition to the teachings of faith, the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum (1599) would standardize the study of Latin, Greek, classical literature, poetry, and philosophy as well as non-European languages, sciences, and the arts. Jesuit schools encouraged the study of vernacular literature and rhetoric, and thereby became important centres for the training of lawyers and public officials.

The Jesuit schools played an important part in winning back to Catholicism a number of European countries which had for a time been predominantly Protestant, notably Poland and Lithuania. Today, Jesuit colleges and universities are located in over one hundred nations around the world. Under the notion that God can be encountered through created things and especially art, they encouraged the use of ceremony and decoration in Catholic ritual and devotion. Perhaps as a result of this appreciation for art, coupled with their spiritual practice of "finding God in all things", many early Jesuits distinguished themselves in the visual and performing arts as well as in music. The theater was a form of expression especially prominent in Jesuit schools.[28]

Jesuit priests often acted as confessors to kings during the early modern period. They were an important force in the Counter-Reformation and in the Catholic missions, in part because their relatively loose structure (without the requirements of living and celebration of the Liturgy of Hours in common) allowed them to be flexible and meet diverse needs arising at the time.[29]

Expansion of the order

[edit]This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. (December 2019) |

After much training and experience in theology, Jesuits went across the globe in search of converts to Christianity. Despite their dedication, they had little success in Asia, except in the Philippines. For instance, early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of Nagasaki in 1580. This was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence.[30] Jesuits did, however, have much success in Latin America. Their ascendancy in societies in the Americas accelerated during the seventeenth century, wherein Jesuits created new missions in Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia. As early as 1603, there were 345 Jesuit priests in Mexico alone.[31]

In 1541, Francis Xavier, one of the original companions of Loyola, arrived in Goa, Portuguese India, to carry out evangelical service in the Indies. In a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, he requested an Inquisition to be installed in Goa to combat heresies like crypto-Judaism and crypto-Islam. Under Portuguese royal patronage, Jesuits thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully expanded their activities to education and healthcare.[32]

In 1594, they founded the first Roman-style academic institution in the East, St. Paul Jesuit College in Macau, China. Founded by Alessandro Valignano, it had a great influence on the learning of Eastern languages (Chinese and Japanese) and culture by missionary Jesuits, becoming home to the first western sinologists such as Matteo Ricci. Jesuit efforts in Goa were interrupted by the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portuguese territories in 1759 by the powerful Marquis of Pombal, the Secretary of State in Portugal.[32]

In 1624, the Portuguese Jesuit António de Andrade founded a mission in Western Tibet. In 1661, two Jesuit missionaries, Johann Grueber and Albert Dorville, reached Lhasa, in Tibet. The Italian Jesuit Ippolito Desideri established a new Jesuit mission in Lhasa and Central Tibet (1716–21) and gained an exceptional mastery of Tibetan language and culture, writing a long and very detailed account of the country and its religion as well as treatises in Tibetan that attempted to refute key Buddhist ideas and establish the truth of Catholic Christianity.

Jesuit missions in the Americas became controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal, where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the Indigenous and slavery. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day Brazil and Paraguay, they formed Indigenous Christian city-states, called "reductions". These were societies set up according to an idealized theocratic model.[31]

The efforts of Jesuits like Antonio Ruiz de Montoya to protect the natives from enslavement by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers contributed to the call for the society's suppression. Jesuit priests such as Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in the 16th century, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and were very influential in the pacification, religious conversion, and education of indigenous nations. They built schools, organized people into villages, and created a writing system for the local languages of Brazil.[31] José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega were the first Jesuits that Ignacio de Loyola sent to the Americas.[33]

Jesuit scholars working in foreign missions were very dedicated in studying the local languages and strove to produce Latinized grammars and dictionaries. This included: Japanese (see Nippo jisho, also known as Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam, "Vocabulary of the Japanese Language", a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written 1603); Vietnamese (Portuguese missionaries created the Vietnamese alphabet,[34][35] which was later formalized by Avignon missionary Alexandre de Rhodes with his 1651 trilingual dictionary); Tupi, the main language of Brazil, and the pioneering study of Sanskrit in the West by Jean François Pons in the 1740s.

Jesuit missionaries were active among indigenous peoples in New France in North America, many of them compiling dictionaries or glossaries of the First Nations and Native American languages they had learned. For instance, before his death in 1708, Jacques Gravier, vicar general of the Illinois Mission in the Mississippi River valley, compiled a Miami–Illinois–French dictionary, considered the most extensive among works of the missionaries.[36] Extensive documentation was left in the form of The Jesuit Relations, published annually from 1632 until 1673.

-

A shunkō-in bell made in Portugal for the Nanbanji Church, run by Jesuits in Japan, 1576–1587

Britain

[edit]Whereas Jesuits were active in Britain in the 1500s, due to the persecution of Catholics in the Elizabethan times, an English province was only established in 1623.[37] The first pressing issue for early Jesuits in what today is the United Kingdom, was to establish places for training priests. In 1579, an English College was opened in Rome. In 1589, a Jesuit seminary was opened at Valladolid.

In 1592, an English College was opened in Seville. In 1614, an English college opened in Louvain. This was the earliest foundation of what was later Heythrop College. Campion Hall, founded in 1896, has been a presence within Oxford University since then.

16th and 17th-century Jesuit institutions intended to train priests were hotbeds for the persecution of Catholics in Britain, where men suspected of being Catholic priests were routinely imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Jesuits were among those killed, including the namesake of Campion Hall, as well as Brian Cansfield, Ralph Corbington, and many others. A number of them were canonized among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

In 2022, four Jesuit churches existed in London, with three other places of worship in England and two in Scotland.[38]

China

[edit]

The Jesuits first entered China through the Portuguese settlement on Macau, where they settled on Green Island and founded St. Paul's College.

The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy,[39] then undergoing its own revolution, to China. The scientific revolution brought by the Jesuits coincided with a time when scientific innovation had declined in China:

[The Jesuits] made efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence, European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture.[40]

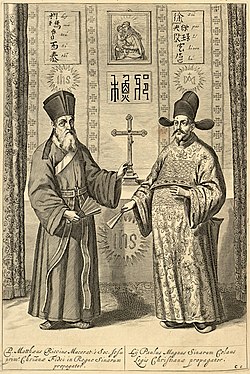

For over a century, Jesuits such as Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci,[41] Diego de Pantoja, Philippe Couplet, Michal Boym, and François Noël refined translations and disseminated Chinese knowledge, culture, history, and philosophy to Europe. Their Latin works popularized the name "Confucius" and had considerable influence on the Deists and other Enlightenment thinkers, some of whom were intrigued by the Jesuits' attempts to reconcile Confucian morality with Catholicism.[42]

Upon the arrival of the Franciscans and other monastic orders, Jesuit accommodation of Chinese culture and rituals led to the long-running Chinese Rites controversy. Despite the personal testimony of the Kangxi Emperor and many Jesuit converts that Chinese veneration of ancestors and Confucius was a nonreligious token of respect, Pope Clement XI's papal decree Cum Deus Optimus ruled that such behavior constituted impermissible forms of idolatry and superstition in 1704.[43]

His legate Tournon and Bishop Charles Maigrot of Fujian, tasked with presenting this finding to the Kangxi Emperor, displayed such extreme ignorance that the emperor mandated the expulsion of Christian missionaries unable to abide by the terms of Ricci's Chinese catechism.[44][45][46][47] Tournon's summary and automatic excommunication for any violators of Clement's decree[48] – upheld by the 1715 bull Ex Illa Die – led to the swift collapse of all the missions in China.[45] The last Jesuits were expelled after 1721.[49]

Ireland

[edit]The first Jesuit school in Ireland was established at Limerick by the apostolic visitor of the Holy See, David Wolfe. Wolfe was sent to Ireland by Pope Pius IV with the concurrence of the third Jesuit superior general, Diego Laynez.[50] He was charged with setting up grammar schools "as a remedy against the profound ignorance of the people".[51]

Wolfe's mission in Ireland initially concentrated on setting the sclerotic Irish Church on a sound footing, introducing the Tridentine Reforms and finding suitable men to fill vacant sees. He established a house of religious women in Limerick known as the Menabochta ("poor women" ) and in 1565 preparations began for establishing a school at Limerick.[52]

At his instigation, Richard Creagh, a priest of the Diocese of Limerick, was persuaded to accept the vacant Archdiocese of Armagh, and was consecrated in Rome in 1564.

This early Limerick school, Crescent College, operated in difficult circumstances. In April 1566, William Good sent a detailed report to Rome of his activities via the Portuguese Jesuits. He informed the Jesuit superior general that he and Edmund Daniel had arrived at Limerick city two years beforehand and their situation there had been perilous. Both had arrived in the city in very bad health, but had recovered due to the kindness of the people.

They established contact with Wolfe, but were only able to meet with him at night, as the English authorities were attempting to arrest the legate. Wolfe charged them initially with teaching to the boys of Limerick, with an emphasis on religious instruction, and Good translated the catechism from Latin into English for this purpose. They remained in Limerick for eight months.[53]

In December 1565, they moved to Kilmallock under the protection of the Earl of Desmond, where they lived in more comfort than the primitive conditions they experienced in Limerick. They were unable to support themselves at Kilmallock and three months later they returned to Limerick in Easter 1566, and strangely set up their house in accommodation owned by the Lord Deputy of Ireland, which was conveyed to them by certain influential friends.[53]

They recommenced teaching at Castle Lane, and imparting the sacraments, though their activities were restricted by the arrival of Royal Commissioners. Good reported that as he was an Englishman, English officials in the city cultivated him and he was invited to dine with them on a number of occasions, though he was warned to exercise prudence and avoid promoting the Petrine primacy and the priority of the Mass amongst the sacraments with his students and congregation, and that his sermons should emphasize obedience to secular princes if he wished to avoid arrest.[53]

The number of scholars in their care was very small. An early example of a school play in Ireland is sent in one of Good's reports, which was performed on the Feast of St. John in 1566. The school was conducted in one large aula, with the students were divided into distinct classes. Good gives a highly detailed report of the curriculum taught. The top class studied the first and second parts of Johannes Despauterius's Commentarli grammatici, and read a few letters of Cicero or the dialogues of Frusius (André des Freux, SJ). The second class committed Donatus' texts in Latin to memory and read dialogues and works by Ēvaldus Gallus. Students in the third class learned Donatus by heart, translated into English rather than Latin. Young boys in the fourth class were taught to read. Progress was slow because there were too few teachers to conduct classes simultaneously.[53]

In the spirit of Ignatius' Roman College founded 14 years before, no fee was requested from pupils. As a result, the two Jesuits lived in very poor conditions and were very overworked with teaching and administering the sacraments to the public. In late 1568, the Castle Lane School, in the presence of Daniel and Good, was attacked and looted by government agents sent by Sir Thomas Cusack during the pacification of Munster.[54]

The political and religious climate had become more uncertain in the lead up to Pope Pius V's formal excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I, which resulted in a new wave of repression of Catholicism in England, Wales and Ireland. At the end of 1568, the Anglican Bishop of Meath, Hugh Brady, was sent to Limerick charged with a Royal Commission to seek out and expel the Jesuits. Daniel was immediately ordered to quit the city and went to Lisbon, where he resumed his studies with the Portuguese Jesuits.[54] Good moved on to Clonmel, before establishing himself at Youghal until 1577.[55]

In 1571, after Wolfe had been captured and imprisoned at Dublin Castle, Daniel persuaded the Portuguese Province to agree a surety for the ransom of Wolfe, who was quickly banished on release. In 1572, Daniel returned to Ireland, but was immediately captured. Incriminating documents were found on his person, which were taken as proof of his involvement with the rebellious cousin of the Earl of Desmond, James Fitzmaurice and a Spanish plot.[56] He was removed from Limerick, and taken to Cork, "just as if he were a thief or noted evildoer". After being court-martialled by the Lord President of Munster, Sir John Perrot, he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason, and refused pardon in return for swearing the Act of Supremacy. His execution was carried out on 25 October 1572. A report of it was sent by Fitzmaurice to the Jesuit Superior General in 1576, where he said that Daniel was "cruelly killed because of me".[57]

With Daniel dead and Wolfe dismissed, the Irish Jesuit foundation suffered a severe setback. Good is recorded as resident at Rome in 1577. In 1586, the seizure of Earl of Desmond's estates resulted in a new permanent Protestant plantation in Munster, making the continuation of the Limerick school impossible for a time. It was not until the early 1600s that the Jesuit mission could again re-establish itself in the city, though the Jesuits kept a low profile existence in lodgings here and there. For instance, a mission led by Fr. Nicholas Leinagh re-established itself at Limerick in 1601,[58] though the Jesuit presence in the city numbered no more than 1 or 2 at a time in the years immediately following.

In 1604, the Lord President of Munster, Sir Henry Brouncker - at Limerick, ordered all Jesuits from the city and Province, and offered £7 to anyone willing to betray a Jesuit priest to the authorities, and £5 for a seminarian.[59] Jesuit houses and schools throughout the province, in the years after, were subject to periodic crackdown and the occasional destruction of schools, imprisonment of teachers and the levying of heavy money penalties on parents are recorded in publications of the time. In 1615–17, the Royal Visitation Books, written up by Thomas Jones, the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, records the suppression of Jesuit schools at Waterford, Limerick and Galway.[60]

In spite of this occasional persecution, the Jesuits were able to exert a degree of discreet influence within the province and in Limerick. For instance in 1606, largely through their efforts, a Catholic named Christopher Holywood was elected Mayor of the city.[61] In 1602, the resident Jesuit had raised a sum of "200 cruzados" for the purpose of founding a hospital in Limerick, though the project was disrupted by a severe outbreak of plague and repression by the Lord President.[62]

The principal activities of the order within Limerick at this time were devoted to preaching, administration of the sacraments and teaching. The school opened and closed intermittently in or around the area of Castle Lane, near Lahiffy's lane. During demolition work stones marked I.H.S., 1642 and 1609 were, in the 19th century, found inserted in a wall behind a tan yard near St Mary's Chapel which, according to Lenihan, were thought to mark the site of an early Jesuit school and oratory. This building, at other times, had also functioned as a dance house and candle factory.[63]

For much of the 1600s, the Limerick Jesuit foundation established a more permanent and stable presence and the Jesuit Annals record a 'flourishing' school at Limerick in the 1640s.[64] During the Confederacy the Jesuits had been able to go about their business unhindered and were invited to preach publicly from the pulpit of St. Mary's Cathedral on 4 occasions. Cardinal Giovanni Rinuccini wrote to the Jesuit general in Rome, praising the work of the Rector of the Limerick College, Fr. William O'Hurley, who was aided by Fr. Thomas Burke.[65]

A few years later, during the Protectorate era, only 18 of the Jesuits resident in Ireland managed to avoid capture by the authorities. Lenihan records that the Limerick Crescent College in 1656 moved to a hut in the middle of a bog, which was difficult for the authorities to find. This foundation was headed up by Fr. Nicholas Punch, who was aided by Frs. Maurice Patrick, Piers Creagh and James Forde. The school attracted a large number of students from around the locality.[66]

At the Restoration of Charles II, the school moved back to Castle Lane, and remained largely undisturbed for the next 40 years, until the surrender of the city to Williamite forces in 1692. In 1671, Dr. James Douley was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Limerick. During his visitation to the diocese, he reported to the Holy See that the Jesuits had a house and "taught schools with great fruit, instructing the youth in the articles of faith and good morals."[67] Douley also noted that this and other Catholic schools operating in the Diocese were also attended by local Protestants.[68]

The Jesuit presence in Ireland, in the so-called Penal era after the Battle of the Boyne, ebbed and flowed. In 1700 they were only 6 or 7, recovering to 25 in 1750. Small Jesuit houses and schools existed at Athlone, Carrick-on-Suir, Cashel, Clonmel, Kilkenny, Waterford, New Ross, Wexford, and Drogheda, as well as Dublin and Galway. At Limerick there appears to have been a long hiatus following the defeat of the Jacobite forces. Fr. Thomas O'Gorman was the first Jesuit to return to Limerick after the siege, arriving in 1728. He took up residence in Jail Lane, near the Castle in the Englishtown. There he opened a school to "impart the rudiments of the classics to the better class youth of the city."[69]

O'Gorman left in 1737 and was succeeded by Fr. John McGrath.[70] Next came Fr. James McMahon, who was a nephew of the Primate of Armagh, Hugh MacMahon. McMahon lived at Limerick for thirteen years until his death in 1751. In 1746, Fr Joseph Morony was sent from Bordeaux to join McMahon and the others.[71] Morony remained at the Jail Lane site teaching at a "high class school" until 1773, when he was ordered to close the school and oratory following the papal suppression of the Society of Jesus,[72] 208 years after its foundation by Wolfe. Morony then went to live in Dublin and worked as a secular priest.

Despite the efforts of the Castle authorities and English government, the Limerick school managed to survive the Protestant Reformation, the Cromwellian invasion and Williamite Wars, and subsequent Penal Laws. It was forced to close, not for religious or confessional reasons, but due to the political difficulties of the Jesuit Order elsewhere.

Following the restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814, the Jesuits gradually re-established a number of their schools throughout the country, starting with foundations at Kildare and Dublin. In 1859, they returned to Limerick at the invitation of the Bishop of Limerick, John Ryan, and re-established a school in Galway the same year.

Canada

[edit]

The first Jesuit mission to Canada was on 25 October 1604, when the Jesuit Father Pierre Coton requested his General Superior Claudio Acquaviva to send two missionaries to Terre-Neuve.[73]: 43 During the French colonization of New France in the 17th century, Jesuits played an active role in North America. Samuel de Champlain established the foundations of the French colony at Québec in 1608. The native tribes that inhabited modern day Ontario, Québec, and the areas around Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay were the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the Huron.[74] Champlain believed that these had souls to be saved, so in 1614 he obtained the Recollects, a reform branch of the Franciscans in France, to convert the native inhabitants.[75]

In 1624, the French Recollects realized the magnitude of their task[76] and sent a delegate to France to invite the Society of Jesus to help with this mission. The invitation was accepted, and Jesuits Jean de Brébeuf, Énemond Massé, and Charles Lalemant arrived in Quebec in 1625.[77] Lalemant is considered to have been the first author of one of the Jesuit Relations of New France, which chronicled their evangelization during the 17th century.

The Jesuits became involved in the Huron mission in 1626 and lived among the Huron peoples. Brébeuf learned the native language and created the first Huron language dictionary. Outside conflict forced the Jesuits to leave New France in 1629 when Quebec was surrendered to the English. In 1632, Quebec was returned to the French under the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye and the Jesuits returned to the Huron territory.[78] After a series of epidemics of European-introduced diseases beginning in 1634, some Huron began to mistrust the Jesuits and accused them of being sorcerers casting spells from their books.[79]

In 1639, Jesuit Jerome Lalemant decided that the missionaries among the Hurons needed a local residence and established Sainte-Marie near present-day Midland, Ontario, which was meant to be a replica of European society.[80] It became the Jesuit headquarters and an important part of Canadian history. Throughout most of the 1640s the Jesuits had modest success, establishing five chapels in Huronia and baptizing more than one thousand Huron out of a population, which may have exceeded 20,000 before the epidemics of the 1630s.[81] However, the Iroquois of New York, rivals of the Hurons, grew jealous of the Hurons' wealth and control of the fur trade system and attacked Huron villages in 1648. They killed missionaries and burned villages, and the Hurons scattered. Both de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant were tortured and killed in the Iroquois raids. For this, they have been canonized as martyrs in the Catholic Church.[82]

The Jesuit Paul Ragueneau burned down Sainte-Marie, instead of allowing the Iroquois the satisfaction of destroying it. By late June 1649, the French and some Christian Hurons built Sainte-Marie II on Christian Island (Isle de Saint-Joseph). Facing starvation, lack of supplies, and constant threats of Iroquois attack, the small Sainte-Marie II was abandoned in June 1650. The remaining Christian Hurons and Jesuits departed for Quebec and Ottawa.[82] As a result of the Iroquois raids and outbreak of disease, many missionaries, traders, and soldiers died.[83] Today, the Huron tribe, also known as the Wyandot, have a First Nations reserve in Quebec, Canada, and three major settlements in the United States.[84]

After the collapse of the Huron nation, the Jesuits undertook the task of converting the Iroquois, something they had attempted in 1642 with little success. In 1653, the Iroquois nation had a fallout with the Dutch. They then signed a peace treaty with the French and a mission was established. The Iroquois soon turned on the French again. In 1658, the Jesuits were having little success and were under constant threat of being tortured or killed.[83] They continued their effort until 1687, when they abandoned their permanent posts in the Iroquois homeland.[85]

In 1700, Jesuits turned to maintaining Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa without establishing new posts.[86] During the Seven Years' War, Quebec was captured by the British in 1759 and New France came under British control. The British barred the immigration of more Jesuits to New France. In 1763, only 21 Jesuits were stationed in New France. In 1773, only 11 Jesuits remained. In 1773, the British crown declared that the Society of Jesus in New France was dissolved.[87]

The dissolution of the order left in place substantial estates and investments, amounting to an income of approximately £5,000 a year. The Council for the Affairs of the Province of Quebec, later succeeded by the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, assumed the task of allocating the funds to suitable recipients, chiefly schools.[88]

In 1842, the Jesuit mission in Quebec was re-established. A number of Jesuit colleges were founded in the decades following. One of these colleges evolved into present-day Laval University.[89]

United States

[edit]In the United States, the order is best known for its missions to the Native Americans in the early 17th century, its network of colleges and universities, and in Europe before 1773, its politically conservative role in the Catholic Counter Reformation.

The Society of Jesus, in the United States, is organized into geographic provinces, each of which being headed by a provincial superior. Today, there are four Jesuit provinces operating in the United States: the USA East, USA Central and Southern, USA Midwest, and USA West Provinces. At their height, there were ten provinces. Though there had been mergers in the past, a major reorganization of the provinces began in early 21st century, with the aim of consolidating into four provinces by 2020.[90]

Ecuador

[edit]The Church of the Society of Jesus (Spanish: La Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús), known colloquially as la Compañía, is a Jesuit church in Quito, Ecuador. It is among the best-known churches in Quito because of its large central nave, which is profusely decorated with gold leaf, gilded plaster and wood carvings. Inspired by two Roman Jesuit churches – the Chiesa del Gesù (1580) and the Chiesa di Sant'Ignazio di Loyola (1650) – la Compañía is one of the most significant works of Spanish Baroque architecture in South America and Quito's most ornate church.

Over the 160 years of its construction, the architects of la Compañía incorporated elements of four architectural styles. Baroque is the most prominent. Mudéjar (Moorish) influence is seen in the geometrical figures on the pillars. Churrigueresque characterizes much of the ornate decoration, especially in the interior walls. The Neoclassical style adorns the Chapel of Saint Mariana de Jesús, which was a winery in its early years.

Mexico

[edit]

The Jesuits in New Spain distinguished themselves in several ways. They had high standards for acceptance to the order and many years of training. They attracted the patronage of elite families whose sons they educated in rigorous newly founded Jesuit colegios ("colleges"), including Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, Colegio de San Ildefonso, and the Colegio de San Francisco Javier, Tepozotlan. Those same elite families hoped that a son with a vocation to the priesthood would be accepted as a Jesuit. Jesuits were also zealous in evangelization of the indigenous, particularly on the northern frontiers.

To support their colegios and members of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits acquired landed estates that were run with the best-practices for generating income in that era. A number of these haciendas were donated by wealthy elites. The donation of a hacienda to the Jesuits was the spark igniting a conflict between 17th-century Bishop Don Juan de Palafox of Puebla and the Jesuit colegio in that city. Since the Jesuits resisted paying the tithe on their estates, this donation effectively took revenue out of the church hierarchy's pockets by removing it from the tithe rolls.[91]

Many of Jesuit haciendas were huge, with Palafox asserting that just two colleges owned 300,000 head of sheep, whose wool was transformed locally in Puebla to cloth; six sugar plantations worth a million pesos and generating an income of 100,000 pesos.[91] The immense Jesuit hacienda of Santa Lucía produced pulque, the alcoholic drink made from fermented agave sap whose main consumers were the lower classes and Indigenous peoples in Spanish cities. Although most haciendas had a free work force of permanent or seasonal labourers, the Jesuit haciendas in Mexico had a significant number of enslaved people of African descent.[92]

The Jesuits operated their properties as an integrated unit with the larger Jesuit order; thus revenues from haciendas funded their colegios. Jesuits did significantly expand missions to the Indigenous in the northern frontier area and a number were martyred, but the crown supported those missions.[91] Mendicant orders that had real estate were less economically integrated, so that some individual houses were wealthy while others struggled economically. The Franciscans, who were founded as an order embracing poverty, did not accumulate real estate, unlike the Augustinians and Dominicans in Mexico.

The Jesuits engaged in conflict with the episcopal hierarchy over the question of payment of tithes, the ten percent tax on agriculture levied on landed estates for support of the church hierarchy from bishops and cathedral chapters to parish priests. Since the Jesuits were the largest religious order holding real estate, surpassing the Dominicans and Augustinians who had accumulated significant property, this was no small matter.[91] They argued that they were exempt, due to special pontifical privileges.[93] Bishop De Palafox took on the Jesuits over this matter and was so soundly defeated that he was recalled to Spain, where he became the bishop of the minor Diocese of Osma.

As elsewhere in the Spanish empire, the Jesuits were expelled from Mexico in 1767. Their haciendas were sold off and their colegios and missions in Baja California were taken over by other orders.[94] Exiled Mexican-born Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero wrote an important history of Mexico while in Italy, a basis for creole patriotism. Andrés Cavo also wrote an important text on Mexican history that Carlos María de Bustamante published in the early 19th century.[95] An earlier Jesuit who wrote about the history of Mexico was Diego Luis de Motezuma (1619–99), a descendant of the Aztec monarchs of Tenochtitlan. Motezuma's Corona mexicana, o Historia de los nueve Motezumas was completed in 1696. He "aimed to show that Mexican emperors were a legitimate dynasty in the 17th-century in the European sense".[96][97]

The Jesuits were allowed to return to Mexico in 1840 when General Antonio López de Santa Anna was once more president of Mexico. Their re-introduction to Mexico was "to assist in the education of the poorer classes and much of their property was restored to them".[98]

-

The main altar of the Jesuit colegio in Tepozotlan, now the Museo Nacional del Virreinato

Northern Spanish America

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

In 1571, the Jesuits arrived in the Viceroyalty of Peru. It was a key area of the Spanish Empire, with a large indigenous populations and huge deposits of silver at Potosí. A major figure in the first wave of Jesuits was José de Acosta (1540–1600), whose 1590 book Historia natural y moral de las Indias introduced Europeans to Spain's American empire, via fluid prose and keen observation and explanation, based on 15 years in Peru and some time in New Spain (Mexico).[99]

The Viceroy of Peru Don Francisco de Toledo urged the Jesuits to evangelize the Indigenous peoples of Peru, wanting to put them in charge of parishes, but Acosta adhered to the Jesuit position that they were not subject to the jurisdiction of bishops and to catechize in Indigenous parishes would bring them into conflict with the bishops. For that reason, the Jesuits in Peru focused on education of elite men rather than the indigenous populations.[99]

To minister to newly arrived African slaves, Alonso de Sandoval (1576–1651) worked at the port of Cartagena de Indias. Sandoval wrote about this ministry in De instauranda Aethiopum salute (1627),[100] describing how he and his assistant Peter Claver, later canonized, met slave transport ships in the harbour, went below decks where 300–600 slaves were chained, and gave physical aid with water, while introducing the Africans to Christianity. In his treatise, he did not condemn slavery or the ill-treatment of slaves, but sought to instruct fellow Jesuits to this ministry and describe how he catechized the slaves.[101]

Rafael Ferrer was the first Jesuit of Quito to explore and found missions in the upper Amazon regions of South America from 1602 to 1610, which belonged to the Audiencia (high court) of Quito that was a part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until it was transferred to the newly created Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. In 1602, Ferrer began to explore the Aguarico, Napo, and Marañon rivers in the Sucumbios region, in what is today Ecuador and Peru. Between 1604 and 1605, he set up missions among the Cofane natives. In 1610, he was martyred by an apostate native.

In 1639, the Audiencia of Quito organized an expedition to renew its exploration of the Amazon river and the Quito Jesuit (Jesuita Quiteño) Cristóbal de Acuña was a part of this expedition. In February 1639, the expedition disembarked from the Napo river. In December 1639, they arrived in what is today Pará, Brazil, on the banks of the Amazon river. In 1641, Acuña published in Madrid a memoir of his expedition to the Amazon river entitled Nuevo Descubrimiento del gran rio de las Amazonas, which for academics became a fundamental reference on the Amazon region.

In 1637, the Jesuits Gaspar Cugia and Lucas de la Cueva from Quito began establishing the Mainas missions in territories on the banks of the Marañón River, around the Pongo de Manseriche region, close to the Spanish settlement of Borja. Between 1637 and 1652 there were 14 missions established along the Marañón River and its southern tributaries, the Huallaga and the Ucayali rivers. Jesuit de la Cueva and Raimundo de Santacruz opened up two new routes of communication with Quito, through the Pastaza and Napo rivers.

Between 1637 and 1715, Samuel Fritz founded 38 missions along the length of the Amazon river, between the Napo and Negro rivers, that were called the Omagua Missions. Beginning in 1705, these missions were continually attacked by the Brazilian Bandeirantes. In 1768, the only Omagua mission that was left was San Joaquin de Omaguas, since it had been moved to a new location on the Napo river away from the Bandeirantes.

In the immense territory of Maynas, the Jesuits of Quito made contact with a number of indigenous tribes which spoke 40 different languages, and founded 173 Jesuit missions, encompassing 150,000 inhabitants. Because of the constant epidemics of smallpox and measles and warfare with other tribes and the Bandeirantes, the number of Jesuit Missions were reduced to 40 by 1744. The Jesuit missions offered the Indigenous people Christianity, iron tools, and a small degree of protection from the slavers and the colonists.[102]

In exchange, the Indigenous had to submit to Jesuit discipline and adopt, at least superficially, a lifestyle foreign to their experience. The population of the missions was sustained by frequent expeditions into the jungle by Jesuits, soldiers, and Christian Indians to capture Indigenous people and force them to return or to settle in the missions.[102] At the time when the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish America in 1767, the Jesuits registered 36 missions run by 25 Jesuits in the Audiencia of Quito – 6 in the Napo and Aguarico Missions and 19 in the Pastaza and Iquitos Missions, with a population at 20,000 inhabitants.[103]

Paraguay

[edit]The Guaraní people of eastern Paraguay and neighboring Brazil and Argentina were in crisis in the early 17th century. Recurrent epidemics of European diseases had reduced their population by up 50 percent and the forced labor of the encomiendas by the Spanish and mestizo colonists had made virtual slaves of many. Franciscan missionaries began establishing missions called reductions in the 1580s.[104] The first Jesuits arrived in Asunción in 1588 and founded their first mission (or reduction) of San Ignacio Guazú in 1609. The objectives of the Jesuits were to make Christians of the Guaraní, impose European values and customs (which were regarded as essential to a Christian life), and isolate and protect the Guaraní from European colonists and slavers.[104][105]

In addition to recurrent epidemics, the Guaraní were threatened by the slave-raiding Bandeirantes from Brazil, who captured natives and sold them as slaves to work in sugar plantations or as concubines and household servants. Having depleted native populations near São Paulo, they discovered the richly populated Jesuit missions. Initially, the missions had few defenses against the slavers and thousands of Guaraní were captured and enslaved.

Beginning in 1631, the Jesuits moved their missions from the Guayrá province (present day Brazil and Paraguay), about 500 km (310 miles) southwest to the three borders region of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil. About 10,000 of 30,000 Guaraní in the missions chose to accompany the Jesuits. In 1641 and 1642, armed by the Jesuits, Guaraní armies defeated the Bandeirantes and ended the worst of the slave trade in their region. From this point on the Jesuit missions enjoyed growth and prosperity, punctuated by epidemics. At the peak of their importance in 1732, the Jesuits presided over 141,000 Guaraní (including a sprinkling of other peoples) who lived in about 30 missions.[106]

The opinions of historians differ with regard to the Jesuit missions. The missions are much-romanticized with the Guaraní portrayed as innocent children of nature and the Jesuits as their wise and benevolent guides to an earthly utopia. "Proponents...highlight that the Jesuits protected the Indians from exploitation and preserved the Guaraní language and other aspects of indigenous culture."[107] "By means of religion," wrote the 18th century philosopher Jean d'Alembert, "the Jesuits established a monarchical authority in Paraguay, founded solely on their powers of persuasion and on their lenient methods of government. Masters of the country, they rendered happy the people under their sway." Voltaire called the Jesuit missions "a triumph of humanity".[108]

Detractors say that "the Jesuits took away the Indians' freedom, forced them to radically change their lifestyle, physically abused them, and subjected them to disease." Moreover, the missions were inefficient and their economic success "depended on subsidies from the Jesuit order, special protection and privileges from the Crown, and the lack of competition"[107] The Jesuits are portrayed as "exploiters" who "sought to create a kingdom independent of the Spanish and Portuguese Crowns."[109]

The Comunero Revolt (1721 to 1735) was a serious protest by Spanish and mestizo Paraguayans against the Jesuit missions. The residents of Paraguay violently protested the pro-Jesuit government of Paraguay, Jesuit control of Guaraní labor, and what they regarded as unfair competition for the market for products such as yerba mate. Although the revolt ultimately failed and the missions remained intact, the Jesuits were expelled from institutions they had created in Asunción.[110] In 1756, the Guaraní protested the relocation of seven missions, fighting (and losing) a brief war with both the Spanish and Portuguese. The Jesuits were accused of inciting the Guaraní to rebel.[111] In 1767, Charles III of Spain (1759–88) expelled the Jesuits from the Americas. The expulsion was part of an effort in the Bourbon Reforms to assert more Spanish control over its American colonies.[112] In total, 78 Jesuits departed from the missions leaving behind 89,000 Guaraní in 30 missions.[113]

Philippines

[edit]The Jesuits were among the original five Catholic religious orders, alongside the Augustinians, Franciscans, Dominicans and Augustinian Recollects, who evangelized the Philippines in support of Spanish colonization.[114] The Jesuits worked particularly hard in converting the Muslims of Mindanao and Luzon from Islam to Christianity, in which case, they were successful among the cities of Zamboanga and Manila.[115] Zamboanga in particular was run like the Jesuit reductions in Paraguay and housed a large population of Peruvian and Latin American immigrants whereas Manila eventually became the capital of the Spanish colony.[116][117]

In addition to missionary work, the Jesuits compiled artifacts and chronicled the precolonial history and culture of the Philippines. Jesuit chronicler Pedro Chirino chronicled the history of the Kedatuan of Madja-as in Panay and its war against Rajah Makatunao of Sarawak as well as the histories of other Visayan kingdoms.[118] Meanwhile, another Jesuit, Francisco Combés, chronicled the history of the Venice of the Visayas, the Kedatuan of Dapitan, its temporary conquest by the Sultanate of Ternate, its re-establishment in Mindanao and its alliance against the Sultanates of Ternate and Lanao as vassals under Christian Spain.

The Jesuits also established the first missions in Hindu-dominated Butuan, to convert it to Christianity.[119] The Jesuits also founded many towns, farms, haciendas, educational institutes, libraries, and an observatory in the Philippines.[120] The Jesuits were instrumental in the sciences of medicine, botany, zoology, astronomy and seismology. They trained the Philippines' second saint, Pedro Calungsod, who was martyred in Guam alongside the Jesuit priest Diego Luis de San Vitores.[121]

The eventual temporary suppression of the Jesuits due their role in anti-colonial and anti-slavery revolts among the Paraguay reductions,[105] alongside cooperation with the Recollects, allowed their vacated parishes to be put under control by the local nationalistic diocesan clergy; the martyrdom of three of them, the diocesan priests known as Gomburza,[122] inspired José Rizal (also Jesuit-educated upon the restoration of the order), who became the Philippines' national hero. He successfully started the Philippine Revolution against Spain.

The Jesuits largely discredited the Freemasons, who claimed responsibility for the American and French Revolutions, by reverting Jose Rizal from Freemasonry back to Catholicism.[123] They argued that since the Philippine Revolution was inspired by the allegedly Masonic ideals behind the French and American revolutions, the French and American Freemasons themselves betrayed their own founding ideals when the American Freemasons annexed the Philippines and killed Filipinos in the Philippine-American War and the French Freemasons assented to the Treaty of Paris (1898),[124][125][126] this is compounded by the fact that American Freemason lodges dismissed the Philippine Revolutionary Freemason lodges as "irregular" and illegitimate.[127] For the remainder of this period, Philippine Freemasonry was subservient to the Grand Lodge of California.[128]

In 1953, after being expelled from China by the Communists, the Jesuits relocated their organization's nexus in Asia from China to the Philippines and brought along a sizeable Chinese diaspora.[129] The Jesuits play a pivotal role in the nation-building of the Philippines with its various Ateneos and educational institutes training the country's intellectual elites.[130][131]

Colonial Brazil

[edit]

Tomé de Sousa, first Governor General of Brazil, brought the first group of Jesuits to the colony. The Jesuits were officially supported by the King, who instructed Tomé de Sousa to give them all the support needed to Christianize the indigenous peoples.

The first Jesuits, guided by Manuel da Nóbrega, Juan de Azpilcueta Navarro, Leonardo Nunes, and later José de Anchieta, established the first Jesuit missions in Salvador and in São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga, the settlement that gave rise to the city of São Paulo. Nóbrega and Anchieta were instrumental in the defeat of the French colonists of France Antarctique by managing to pacify the Tamoio natives, who had previously fought the Portuguese. The Jesuits took part in the foundation of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1565.

The success of the Jesuits in converting the Indigenous peoples is linked to their efforts to understand the native cultures, especially their languages. The first grammar of the Tupi language was compiled by José de Anchieta and printed in Coimbra in 1595. The Jesuits often gathered the natives in communities (the Jesuit reductions), where the natives worked for the community and were evangelized.

The Jesuits had frequent disputes with other colonists who wanted to enslave the natives. The action of the Jesuits saved many natives from being enslaved by Europeans, but also disturbed their ancestral way of life and inadvertently helped spread infectious diseases against which the natives had no natural defenses. Slave labor and trade were essential for the economy of Brazil and other American colonies, and the Jesuits usually did object to the enslavement of African peoples, criticized the conditions of slavery.[132] In cases where individual Jesuit priests criticized the institution of African slavery, they were censored and sent back to Europe.[133]

Suppression and restoration

[edit]The suppression of the Jesuits alienated the colonial empires from the natives they governed in the Americas and Asia, as the Jesuits were active protectors of native rights against the colonial empires. With the suppression of the Order, the profitable Jesuit reductions which gave wealth and protection to natives were sequestered by royal authorities and the natives enslaved. Faced with this suppression; the natives, mestizos, and creoles were galvanized into starting the Latin American Wars of Independence.[134] The suppression of the Jesuits in Portugal, France, the Two Sicilies, Parma, and the Spanish Empire by 1767 was deeply troubling to Pope Clement XIII, the society's defender.[135] On 21 July 1773 his successor, Pope Clement XIV, issued the papal brief Dominus ac Redemptor, decreeing:

Having further considered that the said Company of Jesus can no longer produce those abundant fruits, ... in the present case, we are determining upon the fate of a society classed among the mendicant orders, both by its institute and by its privileges; after a mature deliberation, we do, out of our certain knowledge, and the fulness of our apostolical power, suppress and abolish the said company: we deprive it of all activity whatever. ...And to this end a member of the regular clergy, recommendable for his prudence and sound morals, shall be chosen to preside over and govern the said houses; so that the name of the Company shall be, and is, for ever extinguished and suppressed.

— Dominus ac Redemptor[136]

The suppression was carried out on political grounds in all countries except Prussia for a time, and Russia, where Catherine the Great had forbidden its promulgation. Because millions of Catholics (including many Jesuits) lived in the Polish provinces recently part-annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia, the Society was able to maintain its continuity and carry on its work all through the stormy period of suppression. Subsequently, Pope Pius VI granted formal permission for the continuation of the society in Russia and Poland, with Stanisław Czerniewicz elected superior of the province in 1782. He was followed by Gabriel Lenkiewicz, Franciszek Kareu and Gabriel Gruber until 1805, all elected locally as Temporary Vicars General. Pope Pius VII had resolved during his captivity in France to restore the Jesuits universally, and on his return to Rome he did so without much delay. On 7 August 1814, with the bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum, he reversed the suppression of the society, and therewith another Polish Jesuit, Tadeusz Brzozowski, who had been elected as superior in Russia in 1805, acquired universal jurisdiction. On his death in 1820 the Jesuits were expelled from Russia by tsar Alexander I.

The period following the Restoration of the Jesuits in 1814 was marked by tremendous growth, as evidenced by the large number of Jesuit colleges and universities established during the 19th century. During this time in the United States, 22 of the society's 28 universities were founded or taken over by the Jesuits. It has been suggested that the experience of suppression had served to heighten orthodoxy among the Jesuits. While this claim is debatable, Jesuits were generally supportive of papal authority within the church, and some members became associated with the Ultramontanist movement and the declaration of papal infallibility in 1870.[137]

In Switzerland, the constitution was modified and Jesuits were banished in 1848, following the defeat of the Sonderbund Catholic defence alliance. The ban was lifted on 20 May 1973, when 54.9 per cent of voters accepted a referendum modifying the constitution.[138]

Early 20th century

[edit]In the Constitution of Norway from 1814, a relic from the earlier anti-Catholic laws of Denmark–Norway, Paragraph 2, known as the Jesuit clause, originally read: "The Evangelical-Lutheran religion remains the public religion of the State. Those inhabitants, who confess thereto, are bound to raise their children to the same. Jesuits and monastic orders are not permitted. Jews are still prohibited from entry to the Realm." Jews were first allowed into the realm in 1851 after the famous Norwegian poet Henrik Wergeland had campaigned for this permission. Monastic orders were permitted in 1897, but the ban on Jesuits was only lifted in 1956.[139]

Republican Spain in the 1930s passed laws banning the Jesuits on grounds that they were obedient to a power different from the state. Pope Pius XI wrote about this: "It was an expression of a soul deeply hostile to God and the Catholic religion, to have disbanded the Religious Orders that had taken a vow of obedience to an authority different from the legitimate authority of the State. In this way it was sought to do away with the Society of Jesus – which can well glory in being one of the soundest auxiliaries of the Chair of Saint Peter – with the hope, perhaps, of then being able with less difficulty to overthrow in the near future, the Christian faith and morale in the heart of the Spanish nation, which gave to the Church of God the grand and glorious figure of Ignatius Loyola."[140]

Post-Vatican II

[edit]The 20th century witnessed both growth and decline of the order. Following a trend within the Catholic priesthood at large, Jesuit numbers peaked in the 1950s and have declined steadily since. Meanwhile, the number of Jesuit institutions has grown considerably, due in large part to a post–Vatican II focus on the establishment of Jesuit secondary schools in inner-city areas and an increase in voluntary lay groups inspired in part by the Spiritual Exercises. Among the notable Jesuits of the 20th century, John Courtney Murray was called one of the "architects of the Second Vatican Council" and drafted what eventually became the council's endorsement of religious freedom, Dignitatis humanae.

In Latin America, the Jesuits had significant influence in the development of liberation theology, a movement that was controversial in the Catholic community after the negative assessment of it by Pope John Paul II in 1984.[141]

Under Superior General Pedro Arrupe, social justice and the preferential option for the poor emerged as dominant themes of the work of the Jesuits. When Arrupe was paralyzed by a stroke in 1981, Pope John Paul II, not entirely pleased with the progressive turn of the Jesuits, took the unusual step of appointing the venerable and aged Paolo Dezza for an interim to oversee "the authentic renewal of the Church",[142] instead of the progressive American priest Vincent O'Keefe whom Arrupe had preferred.[143] In 1983, John Paul gave leave for the Jesuits to appoint Peter Hans Kolvenbach as a successor to Arrupe.

On 16 November 1989, six Jesuit priests (Ignacio Ellacuría, Segundo Montes, Ignacio Martín-Baró, Joaquin López y López, Juan Ramon Moreno, and Amado López), Elba Ramos their housekeeper, and Celia Marisela Ramos her daughter, were murdered by the Salvadoran military on the campus of the University of Central America in San Salvador, El Salvador, because they had been labeled as subversives by the government.[144] The assassinations galvanized the society's peace and justice movements, including annual protests at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation at Fort Benning, Georgia, United States, where several of the assassins had been trained under US government sponsorship.[145]

In February 2001, the Jesuit priest Avery Dulles, an internationally known author, lecturer, and theologian, was created a cardinal of the Catholic Church by Pope John Paul II. The son of former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, Avery Dulles was long known for his carefully reasoned argumentation and fidelity to the teaching office of the church. An author of 22 books and over 700 theological articles, Dulles died in December 2008 at Fordham University, where he had taught for twenty years as the Laurence J. McGinley Professor of Religion and Society. He was, at his passing, one of ten Jesuit cardinals in the Catholic Church.

In 2002, Boston College president and Jesuit priest William P. Leahy initiated the Church in the 21st Century program as a means of moving the church "from crisis to renewal". The initiative has provided the society with a platform for examining issues brought about by the worldwide Catholic sex abuse cases, including the priesthood, celibacy, sexuality, women's roles, and the role of the laity.[146]

In April 2005, Thomas J. Reese, editor of the American Jesuit weekly magazine America, resigned at the request of the society. The move was widely published in the media as the result of pressure from the Vatican, following years of criticism by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on articles touching subjects such as HIV/AIDS, religious pluralism, homosexuality, and the right of life for the unborn. Following his resignation, Reese spent a year-long sabbatical at Santa Clara University before being named a fellow at the Woodstock Theological Center in Washington, D.C., and later senior analyst for the National Catholic Reporter. President Barack Obama appointed him to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom in 2014 and again in 2016.[147]

In February 2006, Peter Hans Kolvenbach informed members of the Society of Jesus that, with the consent of Pope Benedict XVI, he intended to step down as superior general in 2008, the year he would turn 80.

On 22 April 2006, during the Feast of Our Lady, Mother of the Society of Jesus, Pope Benedict XVI greeted thousands of Jesuits on pilgrimage to Rome, and took the opportunity to thank God "for having granted to your Company the gift of men of extraordinary sanctity and of exceptional apostolic zeal such as St Ignatius of Loyola, St Francis Xavier, and Blessed Peter Faber". He said "St Ignatius of Loyola was above all a man of God, who gave the first place of his life to God, to his greater glory and his greater service. He was a man of profound prayer, which found its center and its culmination in the daily Eucharistic Celebration."[148]

In May 2006, Benedict XVI wrote a letter to Kolvenbach on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Pope Pius XII's encyclical Haurietis aquas, on devotion to the Sacred Heart, because the Jesuits have always been "extremely active in the promotion of this essential devotion".[149] In his 3 November 2006 visit to the Pontifical Gregorian University, Benedict XVI cited the university as "one of the greatest services that the Society of Jesus carries out for the universal Church".[150]

In January 2008, the 35th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus convened and elected Adolfo Nicolás as the new superior general on 19 January 2008. In a letter to the order, Benedict XVI wrote:[151]

As my Predecessors have said to you on various occasions, the Church needs you, relies on you and continues to turn to you with trust, particularly to reach those physical and spiritual places which others do not reach or have difficulty in reaching. Paul VI's words remain engraved on your hearts: "Wherever in the Church, even in the most difficult and extreme fields, at the crossroads of ideologies, in the social trenches, there has been and there is confrontation between the burning exigencies of man and the perennial message of the Gospel, here also there have been, and there are, Jesuits".

— Address to the 32nd General Congregation of the Jesuits, 3 December 1974; ORE, 12 December, n. 2, p. 4.

In 2013, the Jesuit cardinal Jorge Bergoglio became Pope Francis. Before he became pope, he had been appointed a bishop when he was in "virtual estrangement from the Jesuits" since he was seen as "an enemy of liberation theology" and viewed by others as "still far too orthodox". He was criticized for colluding with the Argentine junta, while biographers characterized him as working to save the lives of other Jesuits.[152][153][154] As a Jesuit pope, he has stressed discernment over following rules, changing the culture of the clergy to steer away from clericalism and to move toward an ethic of service, i.e. to have the "smell of sheep", staying close to the people.[155] After his papal election, Superior General Adolfo Nicolás praised Pope Francis as a "brother among brothers".[152]

In October 2016, the 36th General Congregation convened in Rome, convoked by Nicolás, who had announced his intention to resign at age 80.[156][157][158] On 14 October, the 36th General Congregation of the Society of Jesus elected Arturo Sosa, a Venezuelan, as its thirty-first superior general.[159]

In 2016, the General Congregation that elected Arturo Sosa, asked him to complete the process of discerning Jesuit priorities for the time ahead. Sosa devised a plan that enlisted all Jesuits and their lay collaborators in the process of discernment over a 16-month period. In February 2019, he presented the results of the discernment, a list of four priorities for Jesuit ministries for the next ten years.[160]

- To show the way to God through discernment and the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola;

- To walk with the poor, the outcasts of the world, those whose dignity has been violated, in a mission of reconciliation and justice;

- To accompany young people in the creation of a hope-filled future;

- To collaborate in the care of our Common Home.

Pope Francis gave his approval to these priorities, saying that they were in harmony with the church's present priorities and with the programmatic letter of his pontificate, Evangelii gaudium.[161]

Ignatian spirituality

[edit]The spirituality practiced by the Jesuits, called Ignatian spirituality, ultimately based on the Catholic faith and the gospels, is drawn from the Constitutions, The Letters, and Autobiography, and most specially from Ignatius' Spiritual Exercises, whose purpose is "to conquer oneself and to regulate one's life in such a way that no decision is made under the influence of any inordinate attachment". The Exercises culminate in a contemplation whereby one develops a facility to "find God in all things".

Formation

[edit]The formation (training) of Jesuits seeks to prepare men spiritually, academically, and practically for the ministries they will be called to offer the church and world. Ignatius was strongly influenced by the Renaissance, and he wanted Jesuits to be able to offer whatever ministries were most needed at any given moment and, especially, to be ready to respond to missions (assignments) from the pope. Formation for priesthood normally takes between eight and fourteen years, depending on the man's background and previous education. Final vows are taken several years after that, making Jesuit formation among the longest of any of the religious orders.

Governance of the society

[edit]The society is headed by a Superior General, with the formal title Praepositus Generalis, Latin for "provost-general", more commonly called Father General. He is elected by the General Congregation for life or until he resigns. He is confirmed by the pope and has absolute authority in running the Society. The Superior General of the Jesuits is the Venezuelan Arturo Sosa, who was elected in October 2016.[162]

The Father General is assisted by "assistants". Four are "assistants for provident care" and serve as general advisors and a sort of inner council. Regional assistants head an "assistancy", which is either a geographic area, for instance the North American Assistancy, or an area of ministry, such as higher education. The assistants normally reside with the Father General in Rome and along with others form an advisory council to the General. A vicar general and secretary of the society run day-to-day administration. The General is required to have an admonitor, a confidential advisor whose task is to warn the General honestly and confidentially when he might be acting imprudently or contrary to the church's magisterium. The central staff of the General is known as the Curia.[162]

The society is divided into geographic areas called provinces. Each is headed by a Provincial Superior, formally called Father Provincial, chosen by the Superior General. He has authority over all Jesuits and ministries in his area, and is assisted by a socius who acts as a sort of secretary and chief of staff. With the approval of the Superior General, the Provincial Superior appoints a novice master and a master of tertians to oversee formation, and rectors of local communities of Jesuits.[163] For better cooperation and apostolic efficacy on each continent, the Jesuit provinces are grouped into six Jesuit Conferences worldwide.

Each Jesuit community within a province is normally headed by a rector. He is assisted by a "minister", from the Latin word for "servant", a priest who helps oversee the community's day-to-day needs.[164]

The General Congregation is a meeting of all of the assistants, provincials, and additional representatives who are elected by the professed Jesuits of each province. It meets irregularly and rarely, normally to elect a new superior general or to take up some major policy issues for the order. The Superior General meets more regularly with smaller councils composed of just the provincials.[165]

Statistics

[edit]| Region | Jesuits | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 1,712 | 12% |

| Latin America[167] | 1,859 | 13% |

| South Asia | 3,955 | 27% |

| Asia-Pacific | 1,481 | 10% |

| Europe | 3,386 | 23% |

| North America[168] | 2,046 | 14% |

| Total | 14,439 |

As of 2012[update], the Jesuits formed the largest single religious order of priests and brothers in the Catholic Church.[169] The Jesuits have experienced a decline in numbers in recent decades. In 2022, the society had 14,439 members - 10,432 priests, 837 brothers, 2,587 scholastics, and 583 novices.[166] This represents a 59% percent decline since the Second Vatican Council of 1965, when the society had a total membership of 36,038, of which 20,301 were priests.[170] This decline is most pronounced in Europe and the Americas, with relatively modest membership gains occurring in Asia and Africa.[171][172]