Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bonnie and Clyde

View on Wikipedia

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker (October 1, 1910 – May 23, 1934) and Clyde Chestnut "Champion" Barrow (March 24, 1909 – May 23, 1934) were American outlaws who traveled the Central United States with their gang during the Great Depression, committing a series of criminal acts such as bank robberies, kidnappings, and murders between 1932 and 1934. The couple were known for their bank robberies and multiple murders, although they preferred to rob small stores or rural gas stations. Their exploits captured the attention of the American press and its readership during what is occasionally referred to as the "public enemy era" between 1931 and 1934. On May 23, 1934, they were ambushed and killed on Louisiana Highway 154 in Bienville Parish, Louisiana by a law enforcement posse led by retired Texas Ranger Frank Hamer. They are believed to have murdered at least nine police officers and three civilians.[1][2]

Key Information

The 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, directed by Arthur Penn and starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in the title roles, despite being highly fictionalized and historically inaccurate, was a critical and commercial success which revived interest in the criminals and glamorized them with a romantic aura.[3] The 2019 Netflix film The Highwaymen depicted their manhunt from the point of view of the pursuing lawmen.

Bonnie Parker

[edit]

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker was born in 1910 in Rowena, Texas, the second of three children. Her father, Charles Robert Parker (1884–1914), was a bricklayer who died when Bonnie was four years old.[4] Her widowed mother, Emma (Krause) Parker (1885–1944), moved her family back to her parents' home in Cement City, an industrial suburb in West Dallas where she worked as a seamstress.[5] As an adult, Bonnie wrote poems such as "The Story of Suicide Sal"[6] and "The Trail's End", the latter more commonly known as "The Story of Bonnie and Clyde".[7]

Parker was a bright child who thrived on attention. She enjoyed performing on stage and dreamt of becoming an actress.[8] In her second year in high school, Parker met Roy Thornton (1908–1937). The couple dropped out of school and married on September 25, 1926, six days before her 16th birthday.[9] Their marriage was marred by his frequent absences and brushes with the law and proved to be short-lived. They never divorced, but their paths never crossed again after January 1929. When she died, Parker was still wearing the wedding ring Thornton had given her.[notes 1] Thornton was in prison when he heard of her death, commenting, "I'm glad they jumped out like they did. It's much better than being caught."[10] Sentenced to five years for robbery in 1933 and after attempting several prison breaks from other facilities, Thornton was killed while trying to escape from the Huntsville State Prison on October 3, 1937.[11]

After she left Thornton, Parker moved back in with her mother and worked as a waitress in Dallas. One of her regular customers was postal worker Ted Hinton. In 1932, he joined the Dallas County Sheriff's Department and eventually served as a member of the posse that killed Bonnie and Clyde.[12] Parker briefly kept a diary early in 1929 when she was aged 18, writing of her loneliness, her impatience with life in Dallas, and her love of photography.[13]

Clyde Barrow

[edit]

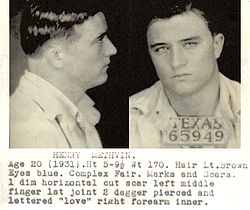

Clyde Chestnut Barrow[14][15] was born in 1909 into a poor farming family in the town of Telico[16] in Ellis County, Texas.[17][18] He was the fifth of seven children of Henry Basil Barrow (1874–1957) and Cumie Talitha Walker (1874–1942). The family moved to Dallas in the early 1920s as part of a wider migration pattern from rural areas to the city, where many settled in the urban slum of West Dallas. The Barrows spent their first months in West Dallas living under their wagon until they got enough money to buy a tent.[19]

Barrow was first arrested in late 1926, at age 17, after running when police confronted him over a rental car that he had failed to return on time. His second arrest was with his brother Buck Barrow soon after, for possession of stolen turkeys. Barrow had some legitimate jobs from 1927 through 1929, but he also cracked safes, robbed stores, and stole cars. He met 19-year-old Parker through a mutual friend in January 1930, and they spent much time together during the following weeks. Their romance was interrupted when Barrow was arrested by Dallas County Sheriff's Deputy Bert Whisnand [citation needed] and convicted of auto theft. He escaped from the McLennan County Jail in Waco, TX, on March 11, 1930, using a gun Parker smuggled into the jail.

Recaptured on March 18, Barrow was sent to Huntsville State Prison in April 1930 and in September he was assigned to the Eastham Prison Farm at the age of 21. He was sexually assaulted while in prison, and he retaliated by attacking and killing his tormentor with a pipe, crushing his skull.[20] This was his first murder. Another inmate who was already serving a life sentence claimed responsibility.

To avoid hard labor in the fields, Barrow purposely had two of his toes amputated in late January 1932, either by another inmate or by himself. Because of this, he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. The amputation slowed him down physically, making it harder to outrun law enforcement and limiting his mobility during his many robberies.[21][22] However, without his knowledge, his mother had successfully petitioned for his release and he was set free six days after his intentional injury.[23] He was paroled from Eastham on February 2, 1932, now a hardened and bitter criminal. His sister Marie said, "Something awful sure must have happened to him in prison because he wasn't the same person when he got out."[24] Fellow inmate Ralph Fults said that he watched Clyde "change from a school boy to a rattlesnake".[25]

In his post-Eastham career, Barrow robbed grocery stores and gas stations at a rate far outpacing the ten or so bank robberies attributed to him and the Barrow Gang. His favorite weapon was the M1918 Browning automatic rifle (BAR).[23] According to John Neal Phillips, Barrow's goal in life was not to gain fame or fortune from robbing banks but to seek revenge against the Texas prison system for the abuses that he had sustained while serving time.[26]

First meeting

[edit]There are several different accounts of Parker and Barrow's first meeting. One of the more credible versions is that they met on January 5, 1930, at the home of Barrow's friend, Clarence Clay, at 105 Herbert Street in West Dallas.[27] Barrow was 20 years old, and Parker was 19. Parker was out of work and staying with a female friend to assist her during her recovery from a broken arm. Barrow dropped by the girl's house while Parker was in the kitchen making hot chocolate.[28]

Armed robbery and murder

[edit]1932: Early robberies and murders

[edit]

After Barrow's release from prison in February 1932, he and Ralph Fults began a series of robberies, primarily of stores and gas stations.[14] Their goal was to collect enough money and firepower to launch a raid against Eastham prison.[26] On April 19, Parker and Fults were captured in a failed hardware store burglary in Kaufman in which they had intended to steal firearms.[29] Parker was released from jail after a few months, when the grand jury failed to indict her. Fults was tried, convicted, and served time. He never rejoined the gang. Parker wrote poetry to pass the time in Kaufman County jail[30][notes 2] and reunited with Barrow within a few weeks of her release.

On April 30, Barrow was the getaway driver in a robbery in Hillsboro during which store owner J.N. Bucher was shot and killed.[31] Bucher's wife identified Barrow from police photographs as one of the shooters, although he had stayed inside the car.

On August 5, Barrow, Raymond Hamilton, and Ross Dyer were drinking moonshine at a country dance in Stringtown, Oklahoma when Sheriff C.G. Maxwell and Deputy Eugene C. Moore approached them in the parking lot. Barrow and Hamilton opened fire, killing Moore and gravely wounding Maxwell.[32][33] Moore was the first law officer whom Barrow and his gang killed. They eventually murdered nine. On October 11, they allegedly killed Howard Hall at his store during a robbery in Sherman, Texas, though some historians consider this unlikely.[34]

W. D. Jones had been a friend of Barrow's family since childhood. He joined Parker and Barrow on Christmas Eve 1932 at the age of 16, and the three left Dallas that night.[35] The next day, Christmas Day 1932, Jones and Barrow murdered Doyle Johnson, a young family man, while stealing his car in Temple.[36] Barrow killed Tarrant County Deputy Malcolm Davis on January 6, 1933, when he, Parker, and Jones wandered into a police trap set for another criminal.[37] The gang had murdered five people since April.

1933: Buck and Blanche Barrow join the gang

[edit]

37°03′06″N 94°31′00″W / 37.051671°N 94.516693°W

On March 22, 1933, Clyde's brother Buck was granted a full pardon and released from prison, and he and his wife Blanche set up housekeeping with Bonnie, Clyde and Jones in a temporary hideout at 3347 1/2 Oakridge Drive in Joplin, Missouri. According to family sources,[38] Buck and Blanche were there to visit; they attempted to persuade Clyde to surrender to law enforcement. The group ran loud, alcohol-fueled card games late into the night in the quiet neighborhood; Blanche recalled that they "bought a case of beer a day".[39] The men came and went noisily at all hours, and Clyde accidentally fired a Browning automatic rifle (BAR) in the apartment while cleaning it.[40] No neighbors went to the house, but one reported suspicions to the Joplin Police Department.

The police assembled a five-man force in two cars on April 13 to confront what they suspected were bootleggers living at the Oakridge Drive address. The Barrow brothers and Jones opened fire, killing Detective Harry L. McGinnis outright and fatally wounding Constable J. W. Harryman.[41][42] Parker opened fire with a BAR as the others fled, forcing Highway Patrol Sergeant G.B. Kahler to duck behind a large oak tree. The .30 caliber bullets from the BAR struck the tree and forced wood splinters into the sergeant's face.[43] Parker got into the car with the others, and they pulled in Blanche from the street where she was pursuing her dog Snow Ball.[44] The surviving officers later testified that they had fired only fourteen rounds in the conflict;[45] one hit Jones on the side, one struck Clyde but was deflected by his suit-coat button, and one grazed Buck after ricocheting off a wall.

The group escaped the police at Joplin but left behind most of their possessions at the apartment, including Buck's parole papers (three weeks old), a large arsenal of weapons, a handwritten poem by Bonnie, and a camera with several rolls of undeveloped film.[46] Police developed the film at The Joplin Globe and found many photos of Barrow, Parker, and Jones posing and pointing weapons at one another.[47] The Globe sent the poem and the photos over the newswire, including a photo of Parker clenching a cigar in her teeth and a pistol in her hand.[notes 3] The Barrow Gang subsequently became front-page news throughout the United States.

The photo of Parker posing with a cigar and a gun became popular. In his book Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde, writer Jeff Guinn noted:

John Dillinger had matinee-idol good looks and Pretty Boy Floyd had the best possible nickname, but the Joplin photos introduced new criminal superstars with the most titillating trademark of all — illicit sex. Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker were wild and young, and undoubtedly slept together.[48]

The group ranged from Texas as far north as Minnesota for the next three months. In May, they tried to rob the bank in Lucerne, Indiana,[49] and robbed the bank in Okabena, Minnesota.[50] They kidnapped Dillard Darby and Sophia Stone at Ruston, Louisiana in the course of stealing Darby's car; this was one of several events between 1932 and 1934 in which they kidnapped police officers or robbery victims.[notes 4] They usually released their hostages far from home, sometimes with money to help them return.[2][51]

Stories of such encounters made headlines, as did the more violent episodes. The Barrow Gang did not hesitate to shoot anyone who got in their way, whether it was a police officer or an innocent civilian. Other members of the gang who committed murder included Hamilton, Jones, Buck Barrow, and Henry Methvin. Eventually, the cold-bloodedness of their murders opened the public's eyes to the reality of their crimes and led to their ends.[52]

The photos entertained the public for a time, but the gang was desperate and discontented, as described by Blanche in her account written while imprisoned in the late 1930s.[53][notes 5] With their new notoriety, their daily lives became more difficult as they tried to evade discovery. Restaurants and motels became less secure; the gang resorted to campfire cooking and bathing in cold streams.[54] The unrelieved round-the-clock proximity of five people in one car gave rise to vicious bickering.[55][notes 6] Jones was the driver when he and Barrow stole a car belonging to Darby in late April, and he used that car to leave the others. He stayed away until June 8.[56]

Barrow failed to see warning signs at a bridge under construction on June 10 while driving with Jones and Parker near Wellington, Texas, and the car flipped into a ravine.[2][57] Sources disagree on whether there was a gasoline fire[58] or if Parker was doused with acid from the car's battery under the floorboards,[59][notes 7] but she sustained third-degree burns to her right leg, so severe that the muscles contracted and caused the leg to "draw up".[60] Jones observed: "She'd been burned so bad none of us thought she was gonna live. The hide on her right leg was gone from her hip down to her ankle. I could see the bone at places."[61]

Parker could hardly walk; she either hopped on her good leg or was carried by Barrow. They got help from a nearby farm family, then kidnapped Collinsworth County Sheriff George Corry and City Marshal Paul Hardy, leaving the two of them handcuffed to a tree outside Erick, Oklahoma. The three rendezvoused with Buck and Blanche and hid in a tourist court near Fort Smith, Arkansas, nursing Parker's burns. Buck and Jones bungled a robbery and murdered Town Marshal Henry D. Humphrey in Alma, Arkansas.[62] The criminals had to flee, despite Parker's grave condition.[63]

Platte City

[edit]

In July 1933, the gang checked into the Red Crown Tourist Court[64] south of Platte City, Missouri. It consisted of two brick cabins joined by garages, and the gang rented both.[64] To the south stood the Red Crown Tavern, a popular restaurant among Missouri Highway Patrolmen, and the gang seemed to go out of their way to draw attention.[65] Blanche registered the party as three guests, but owner Neal Houser could see five people getting out of the car. He noted that the driver backed into the garage "gangster style" for a quick getaway.[66]

41°33′52″N 94°13′44″W / 41.564388°N 94.228942°W

Blanche paid for their cabins with coins rather than bills, and did the same later when buying five dinners and five beers.[67][notes 8] The next day, Houser noticed that his guests had taped newspapers over the windows of their cabin; Blanche again paid for five meals with coins. Her outfit of jodhpur riding breeches[68] also attracted attention; they were not typical attire for women in the area, and eyewitnesses still remembered them 40 years later.[66] Houser told Captain William Baxter of the Highway Patrol, a patron of his restaurant, about the group.[64]

Barrow and Jones went into town[notes 9] to purchase bandages, crackers, cheese, and atropine sulfate to treat Parker's leg.[69] The druggist contacted Sheriff Holt Coffey, who put the cabins under surveillance. Coffey had been alerted by Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas law enforcement to watch for strangers seeking such supplies. The sheriff contacted Captain Baxter, who called for reinforcements from Kansas City, including an armored car.[64] Sheriff Coffey led a group of officers toward the cabins at 11 p.m. on July 20, 1933, armed with Thompson submachine guns.[70]

In the gunfight that ensued, the officers' .45 caliber Thompsons proved no match for Barrow's .30 caliber BAR, stolen on July 7 from the National Guard armory at Enid, Oklahoma.[71] The gang escaped when a bullet short-circuited the horn on the armored car[notes 10] and the police officers mistook it for a cease-fire signal. They did not pursue the retreating Barrow vehicle.[64]

The gang had evaded the law once again, but Buck had been wounded by a bullet that blasted a large hole in the bone of his forehead and exposed his injured brain. Blanche was also nearly blinded by glass fragments.[64][72]

Dexfield Park

[edit]The Barrow Gang camped at Dexfield Park, an abandoned amusement park near Dexter, Iowa, on July 24, 1933.[2][73] Buck was sometimes semiconscious, and he even talked and ate, but his massive head wound and loss of blood were so severe that Barrow and Jones dug a grave for him.[74] Residents noticed their bloody bandages, and officers determined that the campers were the Barrow Gang. Local police officers and approximately 100 spectators surrounded the group, and the Barrows soon came under fire.[73] Barrow, Parker, and Jones escaped on foot.[2][73] Buck was shot in the back, and he and his wife were captured by the officers. Buck died of his head wound and pneumonia after surgery five days later at Kings Daughters Hospital in Perry, Iowa.[73]

For the next six weeks, the remaining perpetrators ranged far afield from their usual area of operations, west to Colorado, north to Minnesota, southeast to Mississippi; yet they continued to commit armed robberies.[75][notes 11] They restocked their arsenal when Barrow and Jones robbed an armory on August 20 at Plattville, Illinois, acquiring three BARs, handguns, and a large quantity of ammunition.[76]

By early September, the gang risked a run to Dallas to see their families for the first time in four months. Jones parted company with them, continuing to Houston where his mother had moved.[2][73][notes 12] He was arrested there without incident on November 16, and returned to Dallas. Through the autumn, Barrow committed several robberies with small-time local accomplices, while his family and Parker's attended to her considerable medical needs.[77]

On November 22, they narrowly evaded arrest while trying to meet with family members near Sowers, Texas. Dallas Sheriff Smoot Schmid, Deputy Bob Alcorn, and Deputy Ted Hinton lay in wait nearby. As Barrow drove up, he sensed a trap and drove past his family's car, at which point Schmid and his deputies stood up and opened fire with machine guns and a BAR. The family members in the crossfire were not hit, but a BAR bullet passed through the car, striking the legs of both Barrow and Parker.[77] They escaped later that night.

On November 28, a Dallas grand jury delivered a murder indictment against Parker and Barrow for the killing – in January of that year, nearly ten months earlier – of Tarrant County Deputy Malcolm Davis;[78] it was Parker's first warrant for murder.

1934: Final run

[edit]

On January 16, 1934, Barrow orchestrated the escape of Hamilton, Methvin, and several others in the "Eastham Breakout".[26] The brazen raid generated negative publicity for Texas, and Barrow seemed to have achieved what historian Phillips suggests was his overriding goal: revenge on the Texas Department of Corrections.[notes 13]

Barrow Gang member Joe Palmer shot Major Joe Crowson during his escape, and Crowson died a few days later in the hospital.[79] This attack attracted the full power of the Texas and federal government to the manhunt for Barrow and Parker. As Crowson struggled for life, prison chief Lee Simmons reportedly promised him that all persons involved in the breakout would be hunted down and killed.[26] All of them eventually were, except for Methvin, who preserved his life by turning on the gang and setting up the ambush of Barrow and Parker.[26]

The Texas Department of Corrections contacted former Texas Ranger Captain Frank Hamer and persuaded him to hunt down the Barrow Gang. He was retired, but his commission had not expired.[80] He accepted the assignment as a Texas Highway Patrol officer, secondarily assigned to the prison system as a special investigator, and was given the specific task of taking down the Barrow Gang.

Hamer was tall, burly, and taciturn, unimpressed by authority and driven by an "inflexible adherence to right, or what he thinks is right".[81] For twenty years, he had been feared and admired throughout Texas as "the walking embodiment of the 'One Riot, One Ranger' ethos".[82] He "had acquired a formidable reputation as a result of several spectacular captures and the shooting of a number of Texas criminals".[83] He was officially credited with 53 kills, and suffered seventeen wounds.[84]

Prison boss Simmons always said publicly that Hamer had been his first choice, although there is evidence that he first approached two other Rangers, both of whom declined because they were reluctant to shoot a woman.[85] Starting on February 10, Hamer became the constant shadow of Barrow and Parker, living out of his car, just a town or two behind them. Three of Hamer's four brothers were also Texas Rangers. Brother Harrison was the best shot of the four, but Frank was considered the most tenacious.[86]

On Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934, at the intersection of Route 114 and Dove Road, near Grapevine, Texas, now Southlake, highway patrolmen H.D. Murphy and Edward Bryant Wheeler stopped their motorcycles thinking a motorist needed assistance. Barrow and Methvin or Parker opened fire with a shotgun and handgun, killing both officers.[87][88] An eyewitness account said that Parker fired the fatal shots and this story received widespread coverage.[89] Methvin later claimed that he fired the first shot after mistakenly assuming that Barrow wanted the officers killed. Barrow joined in, firing at Patrolman Murphy.[51]

During the spring season, the Grapevine killings were recounted in exaggerated detail, affecting public perception. All four Dallas daily papers seized on the story told by the eyewitness, a farmer who claimed to have seen Parker laugh at the way that Murphy's head "bounced like a rubber ball" on the ground as she shot him.[90] The stories claimed that police found a cigar butt "with tiny teeth marks", supposedly those of Parker.[91] Several days later, Murphy's fiancée wore her intended wedding dress to his funeral, attracting photos and newspaper coverage.[92]

The eyewitness's ever-changing story was soon discredited, but the massive negative publicity increased the public clamor for the extermination of the Barrow Gang. The outcry galvanized the authorities into action, and Highway Patrol boss L.G. Phares offered a reward of $1,000 (equivalent to $18,000 in 2024) for "the dead bodies of the Grapevine slayers"—not their capture, just the bodies.[93] Texas Governor Ma Ferguson added another reward of $500 for each of the two killers, which meant that, for the first time, "there was a specific price on Bonnie's head since she was so widely believed to have shot H.D. Murphy".[94]

Public hostility increased five days later when Barrow and Methvin murdered 60-year-old Constable William "Cal" Campbell, a widower and father, near Commerce, Oklahoma.[95] They kidnapped Commerce police chief Percy Boyd, crossed the state line into Kansas, then let him go, giving him a clean shirt, a few dollars, and a request from Parker to tell the world that she did not smoke cigars. Boyd identified both Barrow and Parker to authorities, but he never learned Methvin's name. The resultant arrest warrant for the Campbell murder specified "Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker and John Doe".[96] Historian Knight writes: "For the first time, Bonnie was seen as a killer, actually pulling the trigger—just like Clyde. Whatever chance she had for clemency had just been reduced."[93] The Dallas Journal ran a cartoon on its editorial page, showing an empty electric chair with a sign on it saying "Reserved", adding the words "Clyde and Bonnie".[97]

Ambush and deaths

[edit]

By May 1934, Barrow had 16 warrants outstanding against him for multiple counts of robbery, auto theft, theft, escape, assault, and murder in four states.[98] Hamer, who had begun tracking the gang on February 12, led the posse. He had studied the gang's movements and found that they swung in a circle skirting the edges of five midwestern states, exploiting the "state line" rule that prevented officers from pursuing a fugitive into another jurisdiction. Barrow was consistent in his movements, so Hamer charted his path and predicted where he would go. The gang's itinerary centered on family visits, and they were due to see Methvin's family in Louisiana. Unbeknownst to Hamer, Barrow had designated Methvin's parents' residence as a rendezvous in case they were separated. Methvin had become separated from the rest of the gang in Shreveport. Hamer's posse was composed of six men: Texas officers Hamer, Hinton, Alcorn, and B.M. "Maney" Gault, and Louisiana officers Henderson Jordan and Prentiss Morel Oakley.[99]

32°26′28.21″N 93°5′33.23″W / 32.4411694°N 93.0925639°W

On May 21, the four posse members from Texas were in Shreveport when they learned that Barrow and Parker were planning to visit Ivy Methvin in Bienville Parish that evening. The full posse set up an ambush along Louisiana State Highway 154 south of Gibsland toward Sailes. Hinton recounted that the lawmen were in place by 9 pm, and waited through the whole of the next day (May 22) with no sign of the perpetrators.[100] Other accounts said that the officers set up on the evening of May 22.[101]

At approximately 9:15 am on May 23, the posse was still concealed in the bushes and almost ready to give up when they heard a vehicle approaching at high speed. In their official report, they stated they had persuaded Methvin to position his truck on the shoulder of the road that morning. They hoped Barrow would stop to speak with him, putting his vehicle close to the posse's position in the bushes. The vehicle proved to be the Ford V8 with Barrow at the wheel and he slowed down as hoped. The six lawmen opened fire while the vehicle was still moving. Oakley fired first, probably before any order to do so.[100][102][103] Barrow was shot in the head and died instantly from Oakley's first shot and Hinton reported hearing Parker scream.[100] The officers fired about 130 rounds, emptying each of their weapons into the car.[104][105] The two had survived several bullet wounds over the years in their confrontations with the law. On this day, any of Bonnie Parker's and Clyde Barrow's wounds would have proven to be fatal.[106]

According to statements made by Hinton and Alcorn:

Each of us six officers had a shotgun and an automatic rifle and pistols. We opened fire with the automatic rifles. They were emptied before the car got even with us. Then we used shotguns. There was smoke coming from the car, and it looked like it was on fire. After shooting the shotguns, we emptied the pistols at the car, which had passed us and ran into a ditch about 50 yards on down the road. It almost turned over. We kept shooting at the car even after it stopped. We weren't taking any chances.[104]

Film footage taken by one of the deputies immediately after the ambush shows 112 bullet holes in the vehicle, of which around one quarter struck the couple.[107] The official report by parish coroner J. L. Wade listed 17 entrance wounds on Barrow's body and 26 on that of Parker,[108] including several headshots to each and one that had severed Barrow's spinal column. Undertaker C. F. "Boots" Bailey had difficulty embalming the bodies because of all the bullet holes.[109]

The deafened officers inspected the vehicle and discovered an arsenal, including stolen automatic rifles, sawed-off semi-automatic shotguns, assorted handguns, and several thousand rounds of ammunition, along with fifteen sets of license plates from various states.[105] Hamer stated: "I hate to bust the cap on a woman, especially when she was sitting down, however if it wouldn't have been her, it would have been us."[110] Word of the deaths quickly got around when Hamer, Jordan, Oakley, and Hinton drove into town to telephone their bosses. A crowd soon gathered at the spot. Gault and Alcorn were left to guard the bodies, but they lost control of the jostling, curious throng; one woman cut off bloody locks of Parker's hair and pieces from her dress, which were subsequently sold as souvenirs. Hinton returned to find a man trying to cut off Barrow's trigger finger, and was sickened by what was occurring.[100] Arriving at the scene, the coroner reported:

Nearly everyone had begun collecting souvenirs such as shell casings, slivers of glass from the shattered car windows, and bloody pieces of clothing from the garments of Bonnie and Clyde. One eager man had opened his pocket knife, and was reaching into the car to cut off Clyde's left ear.[111]

Hinton enlisted Hamer's help in controlling the "circus-like atmosphere" and they got people away from the car.[111]

The posse towed the Ford, with the dead bodies still inside, to the Conger Furniture Store & Funeral Parlor in downtown Arcadia, Louisiana. Preliminary embalming was done by Bailey in a small preparation room in the back of the furniture store, as it was common for furniture stores and undertakers to share the same space.[112] The population of the northwest Louisiana town reportedly swelled from 2,000 to 12,000 within hours. Curious throngs arrived by train, horseback, carriage, and plane. Beer normally sold for 15 cents a bottle but it jumped to 25 cents, and sandwiches quickly sold out.[113] Henry Barrow identified his son's body, then sat weeping in a rocking chair in the furniture section.[112]

H.D. Darby was an undertaker at the McClure Funeral Parlor, and Sophia Stone was a home demonstration agent, both from nearby Ruston. Both of them came to Arcadia to identify the bodies[112] because the Barrow gang had kidnapped them[114] in 1933. Parker reportedly had laughed when she discovered that Darby was an undertaker. She remarked that maybe someday he would be working on her;[112] Darby did assist Bailey in the embalming.[112]

Funeral and burial

[edit]

32°52′03″N 96°51′50″W / 32.867416°N 96.863915°W

Bonnie and Clyde wished to be buried side by side, but the Parker family would not allow it. Her mother wanted to grant her final wish to be brought home, but the mobs surrounding the Parker house made that impossible.[115] More than 20,000 attended Parker's funeral, and her family had difficulty reaching her gravesite.[115] Parker's services were held on May 26.[112] Allen Campbell recalled that flowers came from everywhere, including some with cards allegedly from Pretty Boy Floyd and John Dillinger.[112] The largest floral tribute was sent by a group of Dallas city newsboys; the sudden end of Bonnie and Clyde sold 500,000 newspapers in Dallas alone.[116] Parker was buried in the Fishtrap Cemetery, although her body was moved in 1945 to the new Crown Hill Cemetery in Dallas.[112]

Thousands of people gathered outside both Dallas funeral homes, hoping for a chance to view the bodies. Barrow's private funeral was held at sunset on May 25.[112] He was buried in Western Heights Cemetery in Dallas, next to his brother Marvin. The Barrow brothers share a single granite marker with their names on it and an epitaph selected by Clyde: "Gone but not forgotten."[117]

The American National Insurance Company of Galveston, Texas, paid the life insurance policies in full on Barrow and Parker. Since then, the policy of payouts has changed to exclude payouts in cases of deaths caused by any criminal act by the insured.[118]

The six men of the posse were each to receive a one-sixth share of the reward money. Dallas Sheriff Schmid had promised Hinton that this would total some $26,000,[119] but most of the organizations that had pledged reward funds reneged on their pledges. In the end, each lawman earned $200.23 (the equivalent of $4,821.61 in 2025)[120] for his efforts and collected memorabilia.[121]

32°45′56″N 96°50′45″W / 32.765537°N 96.845863°W

By the summer of 1934, new federal statutes made bank robbery and kidnapping federal offenses. The growing coordination of local authorities by the FBI, plus two-way radios in police cars, combined to make it more difficult to carry out series of robberies and murders than it had been just months before. Two months after Bonnie and Clyde were killed in Gibsland, Dillinger was killed on the street in Chicago. Three months after that, Pretty Boy Floyd was killed in Ohio. One month after that, Baby Face Nelson was killed in Illinois.[122]

As of 2018, Parker's niece and last known surviving relative has campaigned to have her aunt buried next to Barrow.[123][124]

Differing accounts

[edit]The members of the posse came from three organizations: Hamer and Gault were both former Texas Rangers then working for the Texas Department of Corrections (DOC), Hinton and Alcorn were employees of the Dallas Sheriff's office, and Jordan and Oakley were Sheriff and Deputy of Bienville Parish, Louisiana. The three duos distrusted one another and kept to themselves,[125] and each had its own agenda in the operation and offered differing narratives of it. Simmons, the head of the Texas DOC, brought another perspective, having effectively commissioned the posse.

Schmid had tried to arrest Barrow in Sowers, Texas in November 1933. Schmid called "Halt!" and gunfire erupted from the outlaw car, which made a quick U-turn and sped away. Schmid's Thompson submachine gun jammed on the first round, and he could not get off one shot. Pursuit of Barrow was impossible because the posse had parked their cars at a distance to prevent them from being seen.[77]

The posse discussed calling "halt", but the four Texans Hamer, Gault, Hinton, and Alcorn "vetoed the idea",[126] telling them that the killers' history had always been to shoot their way out,[127] as had occurred in Platte City, Dexfield Park, and Sowers.[128] When the ambush occurred, Oakley stood up and opened fire, and the other officers opened fire immediately after.[102] Jordan was reported to have called out to Barrow;[129] Alcorn said that Hamer called out;[130] and Hinton claimed that Alcorn did.[100] In another report, each said that they both did.[131] These conflicting claims might have been collegial attempts to divert the focus from Oakley, who later admitted firing too early, but that is merely speculation.[132]

In 1979, Hinton's account of the saga was published posthumously as Ambush: The Real Story of Bonnie and Clyde.[133] His version of the Methvin family's involvement in the planning and execution of the ambush was that the posse had tied Methvin's father Ivy to a tree the previous night to keep him from warning off the couple.[100] Hinton claimed that Hamer made a deal with Ivy: if he kept quiet about being tied up, his son would escape prosecution for the two Grapevine murders.[100] Hinton alleged that Hamer made every member of the posse swear that they would never divulge this secret. Other accounts place Ivy at the center of the action, not tied up but on the road, waving for Barrow to stop.[93][134]

Hinton's memoir suggests that Parker's cigar in the famous "cigar photo" had been a ruse, and that it was retouched as a cigar by darkroom staff at the Joplin Globe while they prepared the photo for publication.[135][notes 14] Guinn says that some people who knew Hinton suspect that "he became delusional late in life".[136]

Victims

[edit]Bonnie and Clyde killed 12 people, including nine law enforcement officers, during their two years of criminal activity from February 1932 to May 1934.

- John Napoleon "JN" Bucher of Hillsboro, Texas: murdered April 30, 1932 in Hillsboro.

- Deputy Eugene Capell Moore of Atoka, Oklahoma: murdered August 5, 1932 in Stringtown.

- Howard Hall of Sherman, Texas: murdered October 11, 1932 in Sherman.

- Doyle Allie Myers Johnson of Temple, Texas: murdered December 26, 1932 in Temple.

- Deputy Malcolm Simmons Davis of Dallas, Texas: murdered January 6, 1933 in Dallas.

- Detective Harry Leonard McGinnis of Joplin, Missouri: murdered April 13, 1933 in Joplin.

- Constable John Wesley "Wes" Harryman of Joplin, Missouri: murdered April 13, 1933 in Joplin.

- Town Marshal Henry Dallas Humphrey of Alma, Arkansas: murdered June 26, 1933 in Alma.

- Prison Guard Major Joseph Crowson of Huntsville, Texas: murdered January 16, 1934 in Houston County, Texas.

- Patrolman Edward Bryan "Ed" Wheeler of Grapevine, Texas: murdered April 1, 1934 near Grapevine.

- Patrolman Holloway Daniel "H.D." Murphy of Grapevine, Texas: murdered April 1, 1934 near Grapevine.

- Constable William Calvin "Cal" Campbell of Commerce, Oklahoma: murdered April 6, 1934 near Commerce.

Aftermath

[edit]Personal effects

[edit]The posse never received the promised bounty on the perpetrators, so they were told to take whatever they wanted from the confiscated items in their car. Hamer appropriated the arsenal[137] of stolen guns and ammunition, plus a box of fishing tackle, under the terms of his compensation package with the Texas DOC.[notes 15] In July, Clyde's mother Cumie wrote to Hamer asking for the return of the guns: "You don't ever want to forget my boy was never tried in no court for murder, and no one is guilty until proven guilty by some court so I hope you will answer this letter and also return the guns I am asking for."[138] There is no record of any response.[138]

Alcorn claimed Barrow's saxophone from the car, but he later returned it to the Barrow family.[139] Posse members took other personal items, such as Parker's clothing. The Parker family asked for them back but were refused,[105][140] and the items were later sold as souvenirs.[141] The Barrow family claimed that Sheriff Jordan kept an alleged suitcase of cash, and writer Jeff Guinn claims that Jordan bought a "barn and land in Arcadia" soon after the event, thereby hinting that the accusation had merit, despite the complete absence of any evidence to the existence of such a suitcase.[139]

Death car

[edit]

Jordan attempted to keep the death car, but Ruth Warren of Topeka, Kansas, the vehicle's legal owner, sued him.[142] Jordan relented and allowed her to claim it in August 1934, still covered with blood and human tissue.[143] The engine still ran, despite the damage the vehicle took during the ambush. Warren picked up the car in Arcadia and drove it to Shreveport, still in its gruesome state. From there, she had it trucked to Topeka.[144]

The bullet-riddled Ford became a popular traveling attraction. The car was displayed at fairs, amusement parks, and flea markets for three decades, and once became a fixture at a Nevada race track. There was a charge of one dollar to sit in it.[145]

In 1988, a casino near Las Vegas purchased the vehicle for about $250,000 (equivalent to $570,000 in 2024). As of 2024[update], the car and the shirt Barrow was wearing when killed are displayed behind a glass panel at the Primm Valley Resort in Primm, Nevada alongside Interstate 15.[146][147]

Barrow's enthusiasm for cars was evident in a letter he wrote from Tulsa, Oklahoma on April 10, 1934, to Henry Ford: "While I still have got breath in my lungs I will tell you what a dandy car you make. I have drove Fords exclusively when I could get away with one. For sustained speed and freedom from trouble the Ford has got every other car skinned and even if my business hasn't been strictly legal it don't hurt anything to tell you what a fine car you got in the V-8." There are some doubts as to the authenticity of the letter.[148]

Gang and family members

[edit]

In February 1935, Dallas and federal authorities arrested and tried twenty family members and friends for aiding and abetting Barrow and Parker. This became known as the "harboring trial" and all twenty either pleaded guilty or were found guilty. The two mothers were jailed for thirty days. Other sentences ranged from two years' imprisonment for Floyd Hamilton, brother of Raymond, to one hour in custody for Barrow's teenage sister Marie.[149] Other defendants included Blanche, Jones, Methvin, and Parker's sister Billie.

Blanche was permanently blinded in her left eye during the 1933 shootout at Dexfield Park. She was taken into custody on the charge of "assault with intent to kill". She was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison, but was paroled in 1939 for good behavior. She returned to Dallas, leaving her life of crime in the past, and lived with her invalid father as his caregiver. In 1940, she married Eddie Frasure. She worked as a taxi cab dispatcher and a beautician, and completed the terms of her parole one year later. She lived in peace with her husband until he died of cancer in 1969.[150]

Warren Beatty approached her to purchase the rights to her name for use in the 1967 film Bonnie and Clyde, and she agreed to the original script. She objected to her characterization by Estelle Parsons in the final film, describing the actress's Academy Award-winning portrayal of her as "a screaming horse's ass". Despite this, she maintained a firm friendship with Beatty. She died from cancer at age 77 on December 24, 1988, and was buried in Dallas's Grove Hill Memorial Park under the name "Blanche B. Frasure".[150]

Barrow cohorts Hamilton and Palmer, who escaped Eastham in January 1934, were recaptured. Both were convicted of murder and executed in the electric chair at Huntsville, Texas on May 10, 1935.[151]

Jones had left Barrow and Parker six weeks after the three of them evaded officers at Dexfield Park in July 1933.[152] He reached Houston and got a job picking cotton, where he was soon discovered and captured. He was returned to Dallas, where he dictated a "confession" in which he claimed to have been kept a prisoner by Barrow and Parker. Some of the more lurid lies that he told concerned the gang's sex lives, and this testimony gave rise to many stories about Barrow's ambiguous sexuality.[153] Jones was convicted of the murder of Doyle Johnson and served a lenient sentence of fifteen years.

He gave an interview to Playboy magazine during the excitement surrounding the 1967 movie: "That Bonnie and Clyde movie made it all look sort of glamorous, but like I told them teenaged boys sitting near me at the drive-in showing: 'Take it from an old man who was there. It was hell. Besides, there's more lawmen nowadays with better ways of catching you. You couldn't get away, anyway. The only way I come through it was because the Good Lord musta been watching over me. But you can't depend on that, neither, because He's got more folks to watch over now than He did then.'"[154]

W.D. Jones was killed on August 20, 1974, in a misunderstanding by a jealous boyfriend of a woman whom he was trying to help.[155]

Methvin was convicted in Oklahoma of the 1934 murder of Constable Campbell at Commerce. He was paroled in 1942 and killed by a train in 1948. He fell asleep drunk on the train tracks, although some have speculated that he was pushed by someone seeking revenge.[156] His father Ivy was killed in 1946 by a hit-and-run driver.[157] Parker's husband Roy Thornton was sentenced to five years in prison for burglary in March 1933. He was killed by guards on October 3, 1937, during an escape attempt from Eastham prison.[10]

Law enforcement

[edit]Hamer returned to a quiet life as a freelance security consultant for oil companies. According to Guinn, "his reputation suffered somewhat after Gibsland"[158] because many people felt that he had not given Barrow and Parker a fair chance to surrender. He made headlines again in 1948 when he and Governor Coke Stevenson unsuccessfully challenged the vote total achieved by Lyndon Johnson during the election for the U.S. Senate. He died in 1955 at the age of 71, after several years of poor health.[159] Bob Alcorn died on May 23, 1964, 30 years to the day after the Gibsland ambush.[157]

Prentiss Oakley admitted to friends that he had fired prematurely.[132] He succeeded Henderson Jordan as sheriff of Bienville Parish in 1940.[132]

On April 1, 2011, officials of the Texas Rangers, Texas Highway Patrol, and Texas Department of Public Safety honored the memory of patrolman Edward Bryan Wheeler, who was murdered along with officer H. D. Murphy by the Barrow gang on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934. They presented the Yellow Rose of Texas commendation to his last surviving sibling, 95-year-old Ella Wheeler-McLeod of San Antonio, giving her a plaque and framed portrait of her brother.[160]

In popular culture

[edit]Films

[edit]Hollywood has treated the story of Bonnie and Clyde several times, including the movies The Bonnie Parker Story (1958),[161] Bonnie and Clyde (1967),[161][162] and The Highwaymen (2019).[163][164]

Music

[edit]The partnership of Bonnie and Clyde has popularized the term "ride-or-die" to describe unwavering loyalty between a duo. Some songs dive deeply into the story of Bonnie and Clyde, narrating their infamous romance and criminal exploits, while others merely reference their names as symbols of rebellion or loyalty, without the lyrics directly relating to their lives. Notable examples include:

- Serge Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot's 1967 single "Bonnie and Clyde".[165][166]

- Georgie Fame's 1967 single "The Ballad of Bonnie and Clyde".[167][168]

- Mel Tormé's 1968 song "A Day in the Life of Bonnie and Clyde" and album of the same name.[169][170]

- Merle Haggard's 1968 single "The Legend of Bonnie and Clyde".[171][172] The same year the song was covered by Tammy Wynette on her album D-I-V-O-R-C-E.[173][174]

- Flatt and Scruggs' 1968 album The Story of Bonnie & Clyde.[175][172]

- Die Toten Hosen's 1996 single "Bonnie & Clyde".[176]

- Bastille's 2025 song "Bonnie & Clyde".[177]

Television

[edit]

32°26′28″N 93°5′33″W / 32.44111°N 93.09250°W

- The Looney Tunes cartoon Bunny and Claude (We Rob Carrot Patches) (1968) is a parody, portraying them as rabbits stealing carrots.[citation needed]

- A television film was broadcast in 1992 and titled Bonnie & Clyde: The True Story.[178]

- In March 2009, Bonnie and Clyde were the subject of a program in the BBC series Timewatch, based in part on gang members' private papers and previously unavailable police documents.[179]

- Bruce Beresford directed the television miniseries Bonnie & Clyde, which aired in 2013.[180]

- In the 2016 episode of Timeless (season 1, episode 9, "Last Ride of Bonnie & Clyde"), Sam Strike portrays Clyde Barrow and Jacqueline Byers portrays Bonnie Parker.[citation needed]

- The story of Bonnie and Clyde is parodied in "Love, Springfieldian Style", an episode from the 19th season of The Simpsons, with Marge and Homer in the titular roles.[citation needed]

- In 2020, Bonnie and Clyde were some of the "featured villains/criminals" of the 9th episode of season 5 of DC's Legends of Tomorrow, The Great British Fake Off, alongside fellow criminal Jack the Ripper.[citation needed]

Theatre

[edit]- Bonnie & Clyde: A Folktale ran as part of the 2008 New York Musical Theater Festival, featuring book and lyrics by Hunter Foster and music by Rick Crom.[181]

- Another musical, Bonnie & Clyde, only loosely inspired by Parker & Barrow, premiered in 2009 with music by Frank Wildhorn, lyrics by Don Black, and book by Ivan Menchell.[182][183]

Video games

[edit]- The 2010 videogame Fallout: New Vegas features the death car of fictional outlaws Vikki and Vance, who are based on the real-life outlaw couple.[184][better source needed]

- The story featured in the 2026 video game Grand Theft Auto VI is rumoured to be related that of Barrow and Parker. The May 26 release date of the game is the same as the date of their funerals.[185][186]

Books

[edit]- Books that are regarded as non-fictional are listed in the bibliography section.

- In 1967, Lancer Books published Bonnie and Clyde, a novelization of the film from the same year, written by Burt Hirschfeld.[187]

- Side By Side: A Novel of Bonnie and Clyde by Jenni L. Walsh is the fictionalized account of Bonnie and Clyde's crime spree, told through the perspective of Bonnie Parker. Published in 2018 by Forge Books (Macmillan Publishers).[188]

Slang

[edit]- The idiomatic phrase "modern-day Bonnie and Clyde" generally refers to a man and a woman who operate together as present-day criminals.[189]

- The colloquial expression "Bonnie and Clyde" is often used to describe a couple that is extremely loyal and willing to do anything for each other, even in the face of danger. In this instance, it is synonymous with the slang phrases "ride-or-die"[190][191] and "ride-or-die chick"; for example, the song "03 Bonnie and Clyde" by Jay Z and Beyoncé Knowles.[citation needed]

- "Bonnie and Clyde Syndrome"[192][193] is the pop culture phrase for hybristophilia—the phenomenon of becoming attracted to, sexually aroused by, or achieving orgasm based on knowledge of, or watching, an outrage or crime take place. For instance, high-profile criminals (e.g. serial killers) such as Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, and Richard Ramirez reportedly received volumes of sexual fan mail and love letters.[194][195]

See also

[edit]- Caril Ann Fugate

- Charles Starkweather

- Gouffé Case

- Jeffrey and Jill Erickson, an American bank robber couple

- List of Depression-era outlaws

- Fa Ziying and Lao Rongzhi

Notes

[edit]- ^ A few months after their breakup, Thornton was convicted and imprisoned for robbery. Parker told her mother, "I didn't get [a divorce] before Roy was sent up, and it looks sort of dirty to file for one now." Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 56

- ^ Parker composed these poems in an old bankbook, which the jailer's wife had given her to use as paper. Some were her own work, and some were songs and poems she copied from memory. She titled the lot Poetry From Life's Other Side. After being released from jail, she either left it behind or gave it to the jailer. In 2007, the bankbook sold for $36,000. Item 5337 Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Bonhams 1793: Fine Art Auctioneers & Valuers Archived February 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Parker did smoke cigarettes, although she never smoked cigars.

- ^ Victims of kidnapping included: Deputy Joe Johns on August 14, 1932; Officer Thomas Persell on January 26, 1933; civilians Dillard Darby and Sophia Stone on April 27, 1933; Sheriff George Corry and Chief Paul Hardy on June 10, 1933; Chief Percy Boyd on April 6, 1934.

- ^ Blanche wrote that she felt "all my hopes and dreams tumbling down around me" as they fled Joplin.

- ^ Barrow's sister Marie described her brother Buck as "the meanest, most hot-tempered" of all her siblings. Phillips, p. 343 n20

- ^ Six witnesses at a farmhouse described battery acid as the culprit; the open-fire story started with the Parker-Cowan-Fortune book; it was repeated in Jones' Playboy interview.

- ^ The gang had many coins because they had broken into the gumball machines at the three service stations that they robbed in Fort Dodge, Iowa, earlier that day. Guinn, pp. 210–11

- ^ Sources are split on this; most say that it was Blanche who went to town, but she recounted it as Clyde and Jones; p. 112

- ^ The armored car was an ordinary automobile that had been fortified with panels of extra boilerplate.

- ^ Guinn writes that their clothes were so bloody after Dexfield that they wore sheets with slits cut for their heads.

- ^ Knight and Davis had a different version, but once they split up, Jones never saw Barrow and Parker again. Knight and Davis, pp. 114–15

- ^ Phillips writes that Barrow had been so focused on this for so long that, after the Eastham raid, "life for Clyde Barrow became anticlimactic…only death remained, and he knew it". Phillips, Running, p. 217.

- ^ But the cigar is shown in other photos from the Joplin rolls shot at the same spot. (Ramsey, pp. 108–109)

- ^ Hamer was interested in the Barrow hunt assignment, but the pay was only a third of what he made working for oil companies. To sweeten the deal, Texas Department of Corrections boss Lee Simmons granted him title to all the guns that the posse would recover from the slain murderers. Almost all the guns, which the gang had stolen from armories, were the property of the National Guard. There was a thriving market for "celebrity" guns, even in 1934 (Guinn, p. 343).

References

[edit]- ^ Jones deposition, October 17, 1933. FBI file 26-4114, Section Sub A Archived June 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, pp. 59–62. FBI Records and Information Archived May 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c d e f Jones, W.D. "Riding with Bonnie and Clyde" Archived March 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Playboy, November 1968. Reprinted at Cinetropic.com.

- ^ Toplin, Robert B. History by Hollywood: The Use and Abuse of the American Past (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1996.) ISBN 0-252-06536-0.

- ^ Strickland, Kristi (1976). "Parker, Bonnie". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved March 7, 2025.

- ^ Guinn, p. 46

- ^ "The Story of Suicide Sal – Bonnie Parker 1932". cinetropic.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ "The Story of Bonnie and Clyde". cinetropic.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ "Read Bonnie Parker's Poem 'The Story of Bonnie and Clyde'". ThoughtCo. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Phillips, p. xxxvi; Guinn, p. 76

- ^ a b "Bonnie & Roy." Archived June 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Bonnie and Clyde's Texas Hideout. Archived February 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 24, 2008.

- ^ Texoso (February 1, 2018). "Roy Glenn Thornton, husband of Bonnie Parker". Texas History Notebook. Retrieved September 24, 2025.

- ^ Guinn, p. 79

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, pp. 55–57

- ^ a b "FBI – Bon and Clyde". FBI. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "Coroner's report". TexasHideout.Tripod.com. July 21, 2008. Archived from the original on August 3, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2008. "Bonnie and Clyde's Texas Hideout". TexasHideout.Tripod.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ "Clyde Barrow". Biography. February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2025.

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, p. xxxv.

- ^ Long, Christopher (June 12, 2010). "Barrow, Clyde Chesnut". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Guinn provides a comprehensive description of West Dallas, p. 20.

- ^ Guinn, p. 76.

- ^ Association, Texas State Historical. "Barrow, Clyde Chesnut". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Barrow, Blanche (2004). My Life with Bonnie and Clyde. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3625-7.

- ^ a b "Bonnie and Clyde (Part 1)". American Experience. Season 24. Episode 4. PBS. January 19, 2016.

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 324 n 9

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e Phillips, John Neal (October 2000). "Bonnie & Clyde's Revenge on Eastham" Archived November 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Historynet.com, originally published in American History Archived May 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bonnie Parker". Biography. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 80

- ^ Guinn, pp. 103–04

- ^ Guinn, p. 109.

- ^ Ramsey, Winston G., ed. (2003). On The Trail of Bonnie and Clyde: Then and Now. London: After The Battle Books. ISBN 1-870067-51-7, p. 53

- ^ Guinn, p. 120

- ^ "Deputy Sheriff Eugene C. Moore". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Powell, Steven (October 11, 2012). "On 80th anniversary, Clyde Barrow no longer said to be Sherman murder". KXII. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ Guinn, p. 147

- ^ Ramsey, pp. 80–85

- ^ "Deputy Malcolm Davis". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, pp. 31–33. Blanche's book tells of the gang's two-week "vacation" in Joplin.

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, p. 45

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, p. 243 n30.

- ^ "Detective Harry L. McGinnis". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Constable J.W. Harryman". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Ballou, James L., Rock in a Hard Place: The Browning Automatic Rifle, Collector Grade Publications (2000), p. 78.

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 114.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 102.

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 115

- ^ Ramsey pp. 108–13.

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (2010). Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 174–76. ISBN 978-1-4711-0575-3. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ "bank_heist". casscountyin.tripod.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2011.

- ^ Ramsey, pp. 118, 122

- ^ a b Anderson, Brian. "Reality less romantic than outlaw legend" Archived February 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Dallas Morning News. April 19, 2003.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 286–88

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, p. 56

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, pp. 116–17

- ^ Jones' Playboy interview, Barrow and Phillips, p. 65

- ^ Treherne, p. 123; Blanche describes the cramped conditions in her book, pp. 70–71.

- ^ "Red River Plunge of Bonnie and Clyde – Marker Number: 4218". Texas Historic Sites Atlas. Texas Historical Commission. 1975. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ James R. Knight, "Incident at Alma: The Barrow Gang in Northwest Arkansas", The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Arkansas Historical Association Winter, 1997) 401. JSTOR 40027888.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 191–94

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 132

- ^ W. D. Jones, Riding with Bonnie and Clyde, Playboy, November 1968

- ^ "Town Marshal Henry D. Humphrey". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 150

- ^ a b c d e f Vasto, Mark. "Local lawmen shoot it out with notorious bandits" Archived May 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Platte County Landmark. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ Knight, James R. and Jonathan Davis (2003). Bonnie and Clyde: A Twenty-First-Century Update. Waco, Texas: Eakin Press. ISBN 1-57168-794-7. p. 100

- ^ a b Guinn, p. 211

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 112.

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 117

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, p. 112

- ^ "Red Crown Incident" Archived May 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. TexasHideout. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 153

- ^ Barrow and Phillips, pp. 119–21

- ^ a b c d e Vasto, Mark. "In Search of Bonnie and Clyde, Part III: Further on up the road". The Landmark. Platte County, MO. Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ Guinn, p. 220

- ^ Guinn, pp. 234–35

- ^ Ramsey, p. 186

- ^ a b c Knight and Davis, p. 118

- ^ "Clyde and Bonnie Names Reported in Slaying Bill", The Dallas Morning News, November 29, 1933, section II, p. 1

- ^ "Major Joe Crowson". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009. "Major" was Crowson's first name, not a military or TDOC rank.

- ^ Frank Hamer and Bonnie & Clyde. Archived June 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

- ^ Webb, p. 531.

- ^ Burrough, p. 228.

- ^ Treherne, p. 172

- ^ Guinn, p. 252

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 354 n3

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 140

- ^ "Patrolman H.D. Murphy". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ "Patrolman Edward Bryan Wheeler". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on November 28, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 284–86

- ^ Guinn, p. 284

- ^ Ft. Worth Star-Telegram, April 2, 1934

- ^ Guinn, p. 285

- ^ a b c Knight and Davis, p. 147

- ^ Guinn, p. 287

- ^ "Constable William Calvin Campbell". The Officer Down Memorial Page. Archived from the original on December 15, 2009. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 217 n12. Methvin's name was added to the warrant later in the summer, and he was eventually convicted and served time for the murder.

- ^ "Cartoon online". The Dallas Journal. May 16, 1934. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^ "Clyde Champion Barrow FBI Criminal Record". The Portal to Texas History. United States Division of Investigation. June 2, 1934. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ "FBI – Bonnie and Clyde". FBI. Archived from the original on September 23, 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hinton, Ted and Larry Grove (1979). Ambush: The Real Story of Bonnie and Clyde. Austin, TX: Shoal Creek Publishers. ISBN 0-88319-041-9.

- ^ Guinn, p. 334.

- ^ a b Knight and Davis, p. 166.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 339–340.

- ^ a b "Took No Chances, Hinton and Alcorn Tell Newspapermen", Dallas Dispatch, May 24, 1934, Reprinted at Census Diggins. Accessed on May 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c The Posse Archived May 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, Texas Hideout. Retrieved May 25, 2008.

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 167.

- ^ Smithsonian Channel:America in Color: the Death of Bonnie and Clyde

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 219 n13

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 171

- ^ Quotes. Archived May 20, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Texashideout. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ a b Milner, E.R. The Lives and Times of Bonnie and Clyde. Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine Southern Illinois University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8093-2552-7. Published 1996.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moshinskie, Dr. James F. "Funerals of the Famous: Bonnie & Clyde." The American Funeral Director, Vol. 130 (No. 10), October 2007, pp. 74–90.

- ^ "Bonnie & Clyde's Demise" Archived May 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Dallas Journal at TexasHideout.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 112

- ^ a b Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p. 175.

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 219.

- ^ Texas Country Reporter, May 25, 2013

- ^ Parker, Cowan and Fortune, p 174

- ^ Hinton, p 192

- ^ "$200 in 1934 → 2025 | Inflation Calculator". www.in2013dollars.com. Retrieved September 24, 2025.

- ^ Guinn, p. 352

- ^ Ramsey, pp. 276–279

- ^ "Should Bonnie and Clyde be buried next to each other? Their descendants hope so". wfaa.com. December 18, 2018.

- ^ D'Angelo, Bob. "Descendants of Bonnie and Clyde want them buried next to each other". dayton-daily-news.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 335–336

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 205

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 166

- ^ Guinn, p. 269

- ^ Associated Press story with a by-line by Jordan, published in the New York Times and Dallas Morning News, May 24, 1934

- ^ Dallas Morning News, May 24, 1934

- ^ Dallas Dispatch, May 24, 1934.

- ^ a b c Guinn, p. 357.

- ^ Ted Hinton, as told to Larry Grove, Ambush: The Real Story of Bonnie and Clyde, Shoal Creek Publishers, 1979

- ^ Treherne, p. 220

- ^ Hinton, pp. 39, 47

- ^ Guinn, p. 413 n

- ^ Phillips, Running, p. 207

- ^ a b Treherne, p. 224

- ^ a b Guinn, p. 343

- ^ Emma Parker letter Archived August 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. TexasHideout. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

- ^ Steele, p ?; Phillips, pp. 209–11.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 234

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 197.

- ^ Ramsey, p. 272

- ^ "Bonnie and Clyde's Death Car, Primm, Nevada". Roadside America. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ Lane, Taylor (March 24, 2024). "How the 'Bonnie and Clyde Death Car' ended up in Primm". Las Vegas Review Journal. Archived from the original on June 24, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ BONNIE & CLYDE EXHIBITION

- ^ "Letter from Clyde Barrow to Henry Ford Praising the Ford V-8 Car, 1934 – The Henry Ford Organization". www.thehenryford.org. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Guinn, pp. 354–355

- ^ a b Barrow and Phillips, p. 249 n

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 188

- ^ Ramsey, p. 196

- ^ Toland, John (1963). The Dillinger Days. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-306-80626-6 (1995 Da Capo ed.), p. 83

- ^ "Riding with Bonnie and Clyde by W.D. Jones". Cinetropic.com. May 23, 1934. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ "Bonnie and Clyde driver loses life to shotgun blasts." The Houston Post, August 21, 1974.

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 190

- ^ a b Guinn, p. 358

- ^ Guinn, p. 356

- ^ Knight and Davis, p. 191

- ^ Davis, Vincent T. "Texas honors officer killed by Bonnie and Clyde, sister given commendation 77 years later", Houston Chronicle, April 2, 2011

- ^ a b Walker, John, ed. (1994). Halliwell's Film Guide. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-273241-2. p. 150

- ^ "The real Bonnie and Clyde". Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Sperlin, Nicole (March 15, 2019). "How The Highwaymen Sets the Record Straight on Bonnie and Clyde". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ "The Highwaymen Is a Pleasant Throwback of a Movie". The Atlantic. March 29, 2019. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

Netflix's latest offering tells the story of Bonnie and Clyde from the perspective of the lawmen—played by Kevin Costner and Woody Harrelson—who pursued and killed them.

- ^ "The Top 100 Alternative Albums of the 1960s (page 27 of 101)". Spin. March 28, 2013. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ "Watch Serge Gainsbourg and Brigitte Bardot's iconic performance of 'Bonnie and Clyde' in 1968 - Far Out Magazine". July 5, 2021.

- ^ Rice, Jo (1982). The Guinness Book of 500 Number One Hits (1st ed.). Enfield, Middlesex: Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 113. ISBN 0-85112-250-7.

- ^ Philip French (August 26, 2007). "Philip French: How violent taboos were blown away The Observer". Observer.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 24, 2025.

- ^ "A Day in the Life of Bonnie and Clyde". Allmusic. Retrieved April 2, 2011.

- ^ Yaquinto, Marilyn (1998). Pump 'em Full of Lead: A Look at Gangsters on Film. Twayne. p. 113.

- ^ Betts, Stephen L. (May 2018). "Flashback: Merle Haggard Takes 'Bonnie and Clyde' to Number One". Rolling Stone.

- ^ a b Treherne, John (1986). The Strange History of Bonnie and Clyde. Stein & Day.

- ^ "The Legend of Bonnie & Clyde". February 25, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "D-I-V-O-R-C-E - Tammy Wynette | Album | AllMusic" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ^ "The Story of Bonnie & Clyde - Flatt & Scruggs" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ^ "Die Toten Hosen // "Bonnie & Clyde" [Offizielles Musikvideo]". May 16, 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Bastille-Bonnie & Clyde (Official Lyric Video)". August 15, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Bonnie and Clyde: The True Story1992". Reelz Channel. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "BBC Two – Timewatch, 2008–2009, The Real Bonnie and Clyde". BBC. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ "First look at A&E Network's 'Bonnie & Clyde' remake: Recast movies & TV roles". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Gans, Andrew (August 20, 2008). "Davis, Wooten, Anderson, Cahoon and More Cast in NYMF's Bonnie and Clyde". Playbill. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (November 22, 2009). "Osnes and Sands Are Shooting Stars of Bonnie & Clyde, the Musical, Opening in CA". Playbill. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- ^ Diamond, Robert (December 1, 2011). "Review Roundup: BONNIE & CLYDE on Broadway - All the Reviews!". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Harkness, Vic (April 14, 2019). "The Fallout New Vegas experience, IRL: Primm".

- ^ "Fans spot Bonnie and Clyde connection in GTA 6's May 26 release". The Times of India. May 5, 2025. Retrieved July 20, 2025.

- ^ Kaur, Tessa (December 5, 2023). "GTA 6 Is Giving Me The Bonnie And Clyde Game I've Always Wanted". TheGamer. Retrieved July 20, 2025.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Burt (1967). Bonny and Clyde (Hodder Paperback ed.). London: Hodder.

- ^ Walsh, Jenni L. (2018). Side by Side: A Novel of Bonnie and Clyde. New York: Forge. ISBN 978-0-7653-9845-1.

- ^ Campbell, Duncan (August 11, 2010). "Yet another modern-day Bonnie and Clyde". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013.

- ^ "Ride or Die". dictionary.com. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Manner, Carrie (June 12, 2018). "Why Ride or Die Culture Promotes Unhealthy Relationships". One Love. One Love Foundation. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Griffiths, Mark. "Passion Victim: A Brief Look at Hybristophilia". Psychology Today. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Puzic, Sonja (July 4, 2014). "Bonnie and Clyde Syndrome: Why some women are attracted to men like Paul Bernardo". CTV News. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Hobbs, Thomas (October 16, 2018). "From Ted Bundy to Jeffrey Dahmer, What It's Like to be Part of a Serial Killer Fandom". NewStatesman. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- ^ Bergeron, Ryan (July 8, 2015). "Killer love: Why people fall in love with murderers". CNN. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barrow, Blanche Caldwell and John Neal Phillips. My Life with Bonnie and Clyde. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.) ISBN 978-0-8061-3715-5.

- Burrough, Bryan. Public Enemies. (New York: The Penguin Press, 2004.) ISBN 1-59420-021-1.

- Guinn, Jeff. Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009.) ISBN 1-4165-5706-7.

- Knight, James R. and Jonathan Davis. Bonnie and Clyde: A Twenty-First-Century Update. (Austin, TX: Eakin Press, 2003.) ISBN 1-57168-794-7.

- Milner, E.R. The Lives and Times of Bonnie and Clyde (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1996.) ISBN 0-8093-2552-7.

- Parker, Emma Krause, Nell Barrow Cowan and Jan I. Fortune. The True Story of Bonnie and Clyde. (New York: New American Library, 1968.) ISBN 0-8488-2154-8. Originally published in 1934 as Fugitives.

- Phillips, John Neal. Running with Bonnie and Clyde, the Ten Fast Years of Ralph Fults. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996, 2002) ISBN 0-8061-3429-1.

- Ramsey, Winston G., ed. On The Trail of Bonnie and Clyde. (London: After The Battle Books, 2003). ISBN 1-870067-51-7.

- Steele, Phillip, and Marie Barrow Scoma. The Family Story of Bonnie and Clyde. (Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2000.) ISBN 1-56554-756-X.

- Treherne, John. The Strange History of Bonnie and Clyde. (New York: Stein and Day, 1984.) ISBN 0-8154-1106-5.

- Webb, Walter Prescott. The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1935.) ISBN 0-292-78110-5.

- Boessenecker, John. Texas Ranger: The Epic Life of Frank Hamer, the Man Who Killed Bonnie and Clyde. (New York: Thomas Dunn Books, 2016.) ISBN 978-1-250-06998-6.

External links

[edit]Bonnie and Clyde

View on GrokipediaEarly Lives and Formative Influences

Bonnie Parker's Background

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker was born on October 1, 1910, in Rowena, Runnels County, Texas, to Charles Robert Parker, a bricklayer, and Emma Krause Parker.[1][3] Her father died of pneumonia in 1914 when she was four years old, leaving the family in financial hardship; her mother then relocated with Bonnie and her two siblings—an older brother, Buster, and younger sister, Billie—to West Dallas, where they resided in makeshift cement houses amid the slum conditions of Eagle Ford Road.[1][4] This rural-to-urban shift exposed Parker to urban poverty during her formative years, though she remained close to her mother, who supported the family through manual labor and remarriage.[1] Parker attended school in Dallas, where she was described by contemporaries as an intelligent and popular student with strong academic performance, but she dropped out after completing the ninth grade to pursue marriage.[1] On September 25, 1926, six days before her sixteenth birthday, she wed high school acquaintance Roy Glenn Thornton, a marriage marked from the outset by his infidelity and involvement in petty theft. The union dissolved within months as Thornton faced repeated arrests, culminating in his imprisonment for burglary in 1929, after which Parker returned to live with her mother while never formally divorcing him.[5] In the years preceding her association with Clyde Barrow, Parker worked as a waitress at establishments in Dallas, including a café during the onset of the Great Depression, reflecting her efforts to sustain herself amid economic strain without any recorded involvement in criminal activity.[1] Her personal writings, including early poems such as "The Street Girl," reveal a preoccupation with themes of urban vice, moral peril, and a rejection of conventional domesticity, suggesting an innate restlessness and attraction to excitement over stability—evident in her choice to wed young and separate from a wayward spouse rather than rebuild independently.[6] These documented inclinations, drawn from her own compositions, underscore deliberate personal decisions toward nonconformity, unprompted by prior legal infractions or external coercion.[1]Clyde Barrow's Background

Clyde Chestnut Barrow was born on March 24, 1909, in Telico, Texas, a small community in Ellis County south of Dallas, into a family of tenant farmers struggling with poverty.[7] He was the sixth of eight children to parents Henry and Cumie Barrow, who operated a succession of failing farms before relocating the family to the industrial slums of West Dallas around 1921 following the collapse of their tenancy.[8] The Barrows lived in makeshift housing amid the oil refineries and junkyards of Cement City, a transient shantytown where economic desperation was widespread but did not universally precipitate criminality.[9] Barrow's initial foray into crime began in his early teens with petty thefts, heavily influenced by his older brother Marvin Ivan "Buck" Barrow, who drew him into local networks of theft and burglary.[10] His first documented arrest came in 1926 at age 17 for stealing chickens or turkeys alongside Buck, resulting in a short jail sentence that failed to deter further offenses.[11] By age 18, Barrow had progressed to automobile theft and burglary, accumulating additional arrests, including one in Waco for attempted car theft as a juvenile and another in 1927 with Buck for possessing stolen property.[12] These repeated violations by his early 20s—predating the 1929 stock market crash—reflected a pattern of volitional escalation rather than solely reactive hardship, contrasting with multitudes of impoverished Texans who pursued manual labor or migration without predation.[10] In a bid for structure, Barrow attempted to enlist in the U.S. Navy in 1926 but was rejected owing to residual effects from a severe childhood illness, possibly malaria or yellow fever, despite having preemptively tattooed "USN" on his arm.[13] He exhibited interests in music, self-teaching guitar and saxophone with aspirations of performance, yet prioritized transient vagrancy and crime over stable employment.[9] Barrow also independently practiced marksmanship, developing proficiency with firearms through personal trial, which amplified his capacity for violence amid a growing aversion to incarceration's rigors, forged in brief early detentions.[10] This self-reinforcing cycle of choices, unmitigated by familial or communal restraints, underscored his trajectory toward habitual lawbreaking independent of broader economic pressures.[14]Relationship and Gang Formation

Initial Meeting and Partnership