Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lernaeocera branchialis

View on Wikipedia

| Lernaeocera branchialis | |

|---|---|

| |

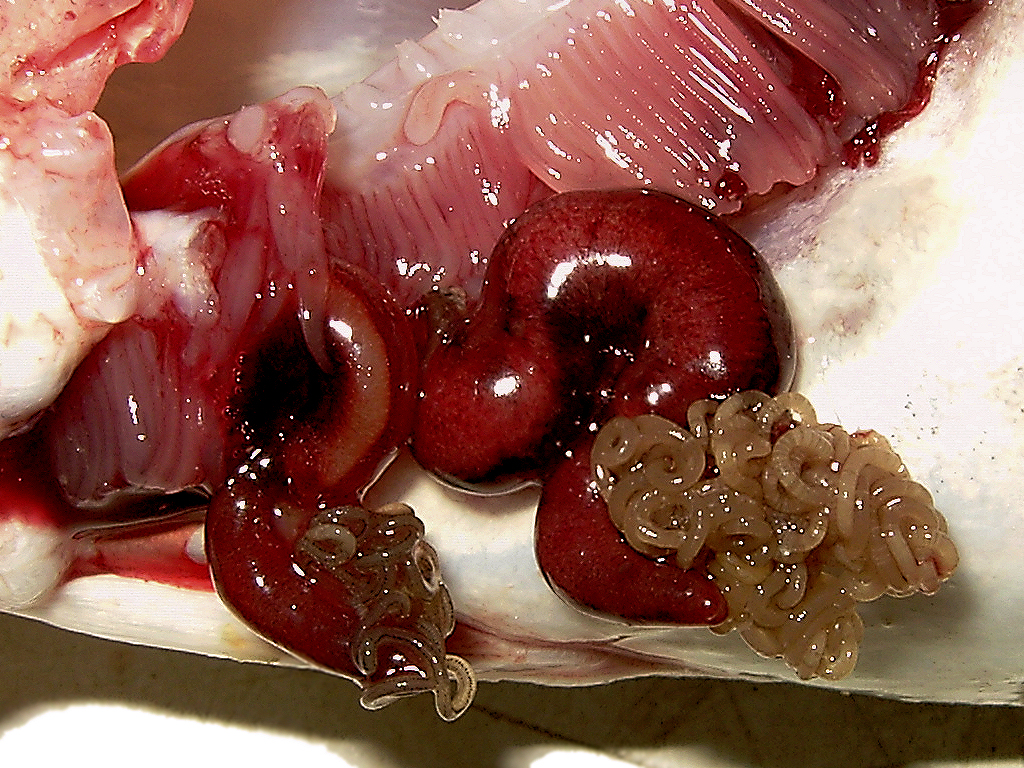

| The gills of a whiting infested by two blood-sucking Lernaeocera branchialis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Copepoda |

| Order: | Siphonostomatoida |

| Family: | Pennellidae |

| Genus: | Lernaeocera |

| Species: | L. branchialis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lernaeocera branchialis | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Lernaeocera branchialis, sometimes called cod worm, is a parasite of marine fish, found mainly in the North Atlantic.[2] It is a marine copepod which starts life as a small pelagic crustacean larva. It is among the largest of copepods, ranging in size from 2 to 3 millimetres (3⁄32 to 1⁄8 inch) when it matures as a copepodid larva to more than 40 mm (1+1⁄2 in) as a sessile adult.

Lernaeocera branchialis is ectoparasitic, which means it is a parasite that lives primarily on the surface of its hosts. It has many life stages, some of which are motile and some of which are sessile. It goes through two parasitic stages, one where it parasitizes as a secondary host a flounder or lumpsucker, and another stage where it parasitizes as a primary host a cod or other fishes of the cod family (gadoids). It negatively impacts the commercial fishing and mariculture of cod-like fish.

Life stages

[edit]The life-cycle of a cod worm involves a complex progression of life stages, including two successive hosts. It comprises "two free-swimming nauplius stages, one infective copepodid stage, four chalimus stages and the adult copepod, each separated by a moult".[3]

The cycle begins with the females laying eggs which hatch into a nauplius, the usual early larval stage of crustaceans.[4] This nauplius I moults about 10 minutes after hatching to produce nauplius II, and 48 hours later, nauplius II moults to a copepodid stage. At this point the copepodid is pelagic and free-swimming with an average length of about 0.5 mm.[3]

The next stage is finding a secondary or intermediate host, a demersal fish like a flounder or lumpfish which is often stationary and therefore easy to catch. The copepodid has only a day to find such a fish and attach itself to the fish's gills.[4]

When they locate such a fish, they capture it with grasping hooks at the front of their body. They penetrate the fish with a thin filament which they use to suck its blood. The nourished cod worms then progress via four moults from the naupliar stage to the mature chalimus stage. At this point the males transfer sperm to the females. Both sexes develop swimming setae, detach from the flounder or lumpfish and again swim freely as pelagic organisms.[4][5]

The female cod worm still resembles a copepod and is 2 to 3 mm long. Females undergo another pelagic quest, searching this time for a definitive or primary host. With her fertilised eggs, she looks for a cod or a fish belonging to the same family as cod, such as a haddock or whiting.[4]

When a suitable definite host is located, females enter the gill chamber. There, while attached to a gill, the female develops a plump, sinusoidal, worm-like body, with a coiled mass of egg strings at the posterior end.[4] Females now measure about 20 mm long, but can grow up to 50 mm.[6] The oral end of the female copepod penetrates the body of the cod until it enters the rear bulb of the host's heart. There, firmly rooted in the cod's circulatory system, the front part of the parasite develops in the shape of antlers or branches on a tree, reaching into the main artery. In this way, while safely tucked beneath the cod's gill cover, the female's deeply embedded oral end can feed on blood while eggs develop and are released into the water column from the posterior end.[4][5]

Behaviour

[edit]It is not known how L. branchialis searches for its fish hosts, but it probably uses chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors, and follows physical clues in the water column such as those provided by haloclines and thermoclines.[3]

Effects on fisheries

[edit]The most serious parasitic crustaceans among fish in general are sea lice.[7] However, L. branchialis is probably the most serious parasitic crustacean among cod. Infestation reduces the efficiency with which food can be utilised, delaying the development of the gonads. Up to 30% loss in weight can occur, with increases in mortality because of open lesions with loss of blood, and possibly occlusion of vessels or aorta.[7] These can have commercial impacts on wild fisheries, making cod-like fishes more expensive to market.[7][8] Gadoids, particularly cod, are emerging marine aquaculture species in some North Atlantic countries. L. branchialis present potential problems for their successful mariculture.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Geoff Boxshall (2011). T. Chad Walter & Geoff Boxshall (ed.). "Lernaeocera branchialis (Linnaeus, 1767)". World Copepoda database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ J. B. Jones (1998). "Distant water sailors: parasitic Copepoda of the open ocean". Journal of Marine Systems. 15 (1–4): 207–214. Bibcode:1998JMS....15..207J. doi:10.1016/S0924-7963(97)00056-0.

- ^ a b c Adam Jonathan Brooker (2007). Aspects of the biology and behaviour of Lernaeocera branchialis (Linnaeus, 1767) (Copepoda : Pennellidae) (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Stirling.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f Bernard E. Matthews (1998). "From host to host". An Introduction to Parasitology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–78. ISBN 978-0-521-57691-8.

- ^ a b Ross Piper (2007). "Cod worm". Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Greenwood Press. pp. 180–182. ISBN 978-0-313-33922-6.

- ^ Z. Kabata (1979). Parasitic Copepoda of British Fishes. London: Ray Society. ISBN 978-0-903874-05-2.

- ^ a b c Tomáš Scholz (1999). "Parasites in cultured and feral fish" (PDF). Veterinary Parasitology. 84 (3–4): 317–335. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(99)00039-4. PMID 10456421. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- ^ Klaus Rohde (1993). Ecology of Marine Parasites: An Introduction to Marine Parasitology (2nd ed.). CAB International. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-85198-845-0.

- ^ Fisheries Research Services (2005) Final report of the Aquaculture Health Joint Working Group sub-group on disease risks and interactions between farmed salmonids and emerging marine aquaculture species Page 29. Scotland. ISBN 0-9546490-8-7

Further reading

[edit]- Adam J. Brooker, Andrew P. Shinn & James E. Bron (2007). "A review of the biology of the parasitic copepod Lernaeocera branchialis (L., 1767) (Copepoda: Pennellidae)". Advances in Parasitology. 65: 297–341. doi:10.1016/S0065-308X(07)65005-2. ISBN 9780123741660. PMID 18063099.

- Larry S. Roberts, John Janovy & Gerald D. Schmidt (2009). Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-128458-5.