Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

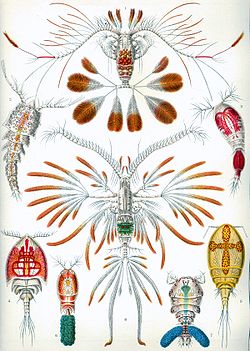

Copepod

View on Wikipedia

| Copepod Temporal range:

Likely early Paleozoic origin

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Superclass: | Multicrustacea |

| Class: | Copepoda H. Milne-Edwards, 1840 |

| Orders | |

Copepods (/ˈkoʊpəpɒd/; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthic (living on the sediments), several species have parasitic phases, and some continental species may live in limnoterrestrial habitats and other wet terrestrial places, such as swamps, under leaf fall in wet forests, bogs, springs, ephemeral ponds, puddles, damp moss, or water-filled recesses of plants (phytotelmata) such as bromeliads and pitcher plants. Many live underground in marine and freshwater caves, sinkholes, or stream beds. Copepods are sometimes used as biodiversity indicators.

As with other crustaceans, copepods have a larval form. For copepods, the egg hatches into a nauplius form, with a head and a tail but no true thorax or abdomen. The larva molts several times until it resembles the adult and then, after more molts, achieves adult development. The nauplius form is so different from the adult form that it was once thought to be a separate species. The metamorphosis had, until 1832, led to copepods being misidentified as zoophytes or insects (albeit aquatic ones), or, for parasitic copepods, 'fish lice'.[1]

Classification and diversity

[edit]Copepods are assigned to the class Copepoda within the superclass Multicrustacea in the subphylum Crustacea.[2] An alternative treatment is as a subclass belonging to class Hexanauplia.[3] They are divided into 10 orders. Some 13,000 species of copepods are known, and 2,800 of them live in fresh water.[4]

Characteristics

[edit]

Copepods vary considerably, but are typically 1 to 2 mm (1⁄32 to 3⁄32 in) long, with a teardrop-shaped body and large antennae. Like other crustaceans, they have an armoured exoskeleton, but they are so small that in most species, this thin armour and the entire body is almost totally transparent. Some polar copepods reach 1 cm (1⁄2 in). Most copepods have a single median compound eye, usually bright red and in the centre of the transparent head. Subterranean species may be eyeless, and members of the genera Copilia and Corycaeus possess two eyes, each of which has a large anterior cuticular lens paired with a posterior internal lens to form a telescope.[5][6][7] Like other crustaceans, copepods possess two pairs of antennae; the first pair is often long and conspicuous.

Free-living copepods of the orders Calanoida, Cyclopoida, and Harpacticoida typically have a short, cylindrical body, with a rounded or beaked head, although considerable variation exists in this pattern. The head is fused with the first one or two thoracic segments, while the remainder of the thorax has three to five segments, each with limbs. The first pair of thoracic appendages is modified to form maxillipeds, which assist in feeding. The abdomen is typically narrower than the thorax, and contains five segments without any appendages, except for some tail-like "rami" at the tip.[8] Parasitic copepods (the other seven orders) vary widely in morphology and no generalizations are possible.

Because of their small size, copepods have no need of any heart or circulatory system (the members of the order Calanoida have a heart, but no blood vessels), and most also lack gills. Instead, they absorb oxygen directly into their bodies. Their excretory system consists of maxillary glands.

Behavior

[edit]The second pair of cephalic appendages in free-living copepods is usually the main time-averaged source of propulsion, beating like oars to pull the animal through the water. However, different groups have different modes of feeding and locomotion, ranging from almost immotile for several minutes (e.g. some harpacticoid copepods) to intermittent motion (e.g., some cyclopoid copepods) and continuous displacements with some escape reactions (e.g. most calanoid copepods).

Some copepods have extremely fast escape responses when a predator is sensed, and can jump with high speed over a few millimetres. Many species have neurons surrounded by myelin (for increased conduction speed), which is very rare among invertebrates (other examples are some annelids and malacostracan crustaceans like palaemonid shrimp and penaeids). Even rarer, the myelin is highly organized, resembling the well-organized wrapping found in vertebrates (Gnathostomata). Despite their fast escape response, copepods are successfully hunted by slow-swimming seahorses, which approach their prey so gradually, it senses no turbulence, then suck the copepod into their snout too suddenly for the copepod to escape.[9]

Several species are bioluminescent and able to produce light. It is assumed this is an antipredatory defense mechanism.[10]

Finding a mate in the three-dimensional space of open water is challenging. Some copepod females solve the problem by emitting pheromones, which leave a trail in the water that the male can follow.[11] Copepods experience a low Reynolds number and therefore a high relative viscosity. One foraging strategy involves chemical detection of sinking marine snow aggregates and taking advantage of nearby low-pressure gradients to swim quickly towards food sources.[12]

Diet

[edit]Most free-living copepods feed directly on phytoplankton, catching cells individually. A single copepod can consume up to 373,000 phytoplankton per day.[13] They generally have to clear the equivalent to about a million times their own body volume of water every day to cover their nutritional needs.[14] Some of the larger species are predators of their smaller relatives. Many benthic copepods eat organic detritus or the bacteria that grow in it, and their mouth parts are adapted for scraping and biting. Herbivorous copepods, particularly those in rich, cold seas, store up energy from their food as oil droplets while they feed in the spring and summer on plankton blooms. These droplets may take up over half of the volume of their bodies in polar species. Many copepods (e.g., fish lice like the Siphonostomatoida) are parasites, and feed on their host organisms. In fact, three of the 10 known orders of copepods are wholly or largely parasitic, with another three comprising most of the free-living species.[15]

Life cycle

[edit]

Most nonparasitic copepods are holoplanktonic, meaning they stay planktonic for all of their lifecycles, although harpacticoids, although free-living, tend to be benthic rather than planktonic. During mating, the male copepod grips the female with his first pair of antennae, which is sometimes modified for this purpose. The male then produces an adhesive package of sperm and transfers it to the female's genital opening with his thoracic limbs. Eggs are sometimes laid directly into the water, but many species enclose them within a sac attached to the female's body until they hatch. In some pond-dwelling species, the eggs have a tough shell and can lie dormant for extended periods if the pond dries up.[8]

Eggs hatch into nauplius larvae, which consist of a head with a small tail, but no thorax or true abdomen. The nauplius moults five or six times, before emerging as a "copepodid larva". This stage resembles the adult, but has a simple, unsegmented abdomen and only three pairs of thoracic limbs. After a further five moults, the copepod takes on the adult form. The entire process from hatching to adulthood can take a week to a year, depending on the species and environmental conditions such as temperature and nutrition (e.g., egg-to-adult time in the calanoid Parvocalanus crassirostris is ~7 days at 25 °C (77 °F) but 19 days at 15 °C (59 °F).[16]

Biophysics

[edit]Copepods jump out of the water - porpoising. The biophysics of this motion has been described by Waggett and Buskey 2007 and Kim et al 2015.[17]

Ecology

[edit]

Planktonic copepods are important to global ecology and the carbon cycle. They are usually the dominant members of the zooplankton, and are major food organisms for small fish such as the dragonet, banded killifish, Alaska pollock, and other crustaceans such as krill in the ocean and in fresh water. Some scientists say they form the largest animal biomass on earth.[19] Copepods compete for this title with Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba). C. glacialis inhabits the edge of the Arctic icepack, especially in polynyas where light (and photosynthesis) is present, in which they alone comprise up to 80% of zooplankton biomass. They bloom as the ice recedes each spring. The ongoing large reduction in the annual ice pack minimum may force them to compete in the open ocean with the much less nourishing C. finmarchicus, which is spreading from the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea into the Barents Sea.[20]

Because of their smaller size and relatively faster growth rates, and because they are more evenly distributed throughout more of the world's oceans, copepods almost certainly contribute far more to the secondary productivity of the world's oceans, and to the global ocean carbon sink than krill, and perhaps more than all other groups of organisms together. The surface layers of the oceans are believed to be the world's largest carbon sink, absorbing about 2 billion tons of carbon a year, the equivalent to perhaps a third of human carbon emissions, thus reducing their impact. Many planktonic copepods feed near the surface at night, then sink (by changing oils into more dense fats)[21][22] into deeper water during the day to avoid visual predators. Their moulted exoskeletons, faecal pellets, and respiration at depth all bring carbon to the deep sea.

About half of the estimated 14,000 described species of copepods are parasitic[23] [24] and many have adapted extremely modified bodies for their parasitic lifestyles.[25] They attach themselves to bony fish, sharks, marine mammals, and many kinds of invertebrates such as corals, other crustaceans, molluscs, sponges, and tunicates. They also live as ectoparasites on some freshwater fish.[26]

Copepods as parasitic hosts

[edit]In addition to being parasites themselves, copepods are subject to parasitic infection. The most common parasites are marine dinoflagellates of the genus Blastodinium, which are gut parasites of many copepod species.[27][28] Twelve species of Blastodinium are described, the majority of which were discovered in the Mediterranean Sea.[27] Most Blastodinium species infect several different hosts, but species-specific infection of copepods does occur. Generally, adult copepod females and juveniles are infected.

During the naupliar stage, the copepod host ingests the unicellular dinospore of the parasite. The dinospore is not digested and continues to grow inside the intestinal lumen of the copepod. Eventually, the parasite divides into a multicellular arrangement called a trophont.[29] This trophont is considered parasitic, contains thousands of cells, and can be several hundred micrometers in length.[28] The trophont is greenish to brownish in color as a result of well-defined chloroplasts. At maturity, the trophont ruptures and Blastodinium spp. are released from the copepod anus as free dinospore cells. Not much is known about the dinospore stage of Blastodinium and its ability to persist outside of the copepod host in relatively high abundances.[30]

The copepod Calanus finmarchicus, which dominates the northeastern Atlantic coast, has been shown to be greatly infected by this parasite. A 2014 study in this region found up to 58% of collected C. finmarchicus females to be infected. In this study, Blastodinium-infected females had no measurable feeding rate over a 24-hour period. This is compared to uninfected females which, on average, ate 2.93 × 104 cells per day.[29] Blastodinium-infected females of C. finmarchicus exhibited characteristic signs of starvation, including decreased respiration, fecundity, and fecal pellet production. Though photosynthetic, Blastodinium spp. procure most of their energy from organic material in the copepod gut, thus contributing to host starvation.[28] Underdeveloped or disintegrated ovaries and decreased fecal pellet size are a direct result of starvation in female copepods.[31] Parasitic infection by Blastodinium spp. could have serious ramifications on the success of copepod species and the function of entire marine ecosystems. Blastodinium parasitism is not lethal, but has negative impacts on copepod physiology, which in turn may alter marine biogeochemical cycles.

Freshwater copepods of the Cyclops genus are the intermediate host of the Guinea worm (Dracunculus medinensis), the nematode that causes dracunculiasis disease in humans. This disease may be close to being eradicated through efforts by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and the Carter Center.[32]

Copepods are known hosts of Vibrio bacteria, including pathogenic species. The Vibrio attach to the copepod's chitinous carapace, wearing it away to create a niche to stay. They are more protected from ecological stressors when attached to copepods and have an easy dispersal method. Vibrio are not known to infect copepods, but the degradation of the carapace is presumably detrimental to the copepod.[33][34]

Copepods are infected by a variety of marine fungi including Metschnikowia species, and this can be lethal. They are also parasitized by tapeworms, isopods, and many kinds of protist, including Ellobiopsidae, Ciliates, and Sporozoans.[35]

Evolution

[edit]

Despite their modern abundance, due to their small size and fragility, copepods are extremely rare in the fossil record. The oldest known fossils of copepods are from the late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) of Oman, around 303 million years old, which were found in a clast of bitumen from a glacial diamictite. The copepods present in the bitumen clast were likely residents of a subglacial lake which the bitumen had seeped upwards through while still liquid, before the clast subsequently solidified and was deposited by glaciers. Though most of the remains were undiagnostic, at least some likely belonged to the extant harpacticoid family Canthocamptidae, suggesting that copepods had already substantially diversified by this time.[36] Possible microfossils of copepods are known from the Cambrian of North America.[37][38] Transitions to parasitism have occurred within copepods independently at least 14 different times, with the oldest record of this being from damage to fossil echinoids done by cyclopoids from the Middle Jurassic of France, around 168 million years old.[39]

Practical aspects

[edit]In marine aquaria

[edit]Live copepods are used in the saltwater aquarium hobby as a food source and are generally considered beneficial in most reef tanks. They are scavengers and also may feed on algae, including coralline algae. Live copepods are popular among hobbyists who are attempting to keep particularly difficult species such as the mandarin dragonet or scooter blenny. They are also popular to hobbyists who want to breed marine species in captivity. In a saltwater aquarium, copepods are typically stocked in the refugium.

Water supplies

[edit]Copepods are sometimes found in public main water supplies, especially systems where the water is not mechanically filtered,[40] such as New York City, Boston, and San Francisco.[41] This is not usually a problem in treated water supplies. In some tropical countries, such as Peru and Bangladesh, a correlation has been found between copepods' presence and cholera in untreated water, because the cholera bacteria attach to the surfaces of planktonic animals. The larvae of the guinea worm must develop within a copepod's digestive tract before being transmitted to humans. The risk of infection with these diseases can be reduced by filtering out the copepods (and other matter), for example with a cloth filter.[42]

Copepods have been used successfully in Vietnam to control disease-bearing mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti that transmit dengue fever and other human parasitic diseases.[43][44]

The copepods can be added to water-storage containers where the mosquitoes breed.[40] Copepods, primarily of the genera Mesocyclops and Macrocyclops (such as Macrocyclops albidus), can survive for periods of months in the containers, if the containers are not completely drained by their users. They attack, kill, and eat the younger first- and second-instar larvae of the mosquitoes. This biological control method is complemented by community trash removal and recycling to eliminate other possible mosquito-breeding sites. Because the water in these containers is drawn from uncontaminated sources such as rainfall, the risk of contamination by cholera bacteria is small, and in fact no cases of cholera have been linked to copepods introduced into water-storage containers. Trials using copepods to control container-breeding mosquitoes are underway in several other countries, including Thailand and the southern United States. The method, though, would be very ill-advised in areas where the guinea worm is endemic.[why?]

Incidental, religious curiosa

[edit]The presence of copepods in the New York City water supply system has caused problems for some Jewish people who observe kashrut. Copepods, being crustaceans, are not kosher, nor are they quite small enough to be ignored as nonfood microscopic organisms, since some specimens can be seen with the naked eye. Hence, large specimens are certainly non-Kosher. However, some species are visible to the naked eye, but are small enough that they only appear as little white specks. These are problematic, as it is a question as to whether they are considered visible enough to be non-Kosher.

When a group of rabbis in Brooklyn, New York, discovered these copepods in the summer of 2004, they triggered such debate in rabbinic circles that some observant Jews felt compelled to buy and install filters for their water.[45] The water was ruled kosher by posek Yisrael Belsky, chief posek of the OU and one of the most scientifically literate poskim of his time.[46] Meanwhile, Rabbi Dovid Feinstein, based on the ruling of Rabbi Yosef Shalom Elyashiv - the two widely considered to be the greatest poskim of their time - ruled it was not kosher until filtered.[47] Several major kashrus organizations (e.g OU Kashrus[48] and Star-K[49]) require tap water to have filters.

In popular culture

[edit]The Nickelodeon television series SpongeBob SquarePants features a copepod named Sheldon J. Plankton as a recurring character.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Damkaer, David (2002). The Copepod's Cabinet: A Biographical and Bibliographical History. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-240-5.

- ^ World of Copepods Database. Walter, T.C.; Boxshall, G. (eds.). "Copepoda". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Copepoda". www.marinespecies.org. Archived from the original on 2019-06-30. Retrieved 2019-06-28.

- ^ Geoff A. Boxhall; Danielle Defaye (2008). "Global diversity of copepods (Crustacea: Copepoda) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 195–207. Bibcode:2008HyBio.595..195B. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9014-4. S2CID 31727589.

- ^ Ivan R. Schwab (2012). Evolution's Witness: How Eyes Evolved. Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-536974-8.

- ^ Charles B. Miller (2004). Biological Oceanography. John Wiley & Sons. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-632-05536-4.

- ^ R. L. Gregory, H. E. Ross & N. Moray (1964). "The curious eye of Copilia" (PDF). Nature. 201 (4925): 1166–1168. Bibcode:1964Natur.201.1166G. doi:10.1038/2011166a0. PMID 14151358. S2CID 4157061. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2018-06-15.

- ^ a b Robert D. Barnes (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 683–692. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ "Seahorses stalk their prey by stealth". BBC News. November 26, 2013. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ Takenaka, Yasuhiro; Yamaguchi, Atsushi; Shigeri, Yasushi (April 7, 2017). "A light in the dark: ecology, evolution and molecular basis of copepod bioluminescence". Journal of Plankton Research. 39 (3): 369–378. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbx016.

- ^ David B. Dusenbery (2009). Living at Micro Scale. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6.

- ^ Lombard, F.; Koski, M.; Kiørboe, T. (January 2013). "Copepods use chemical trails to find sinking marine snow aggregates" (PDF). Limnology and Oceanography. 58 (1): 185–192. Bibcode:2013LimOc..58..185L. doi:10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0185. S2CID 55896867.

- ^ "Small Is Beautiful, Especially for Copepods - The Vineyard Gazette". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- ^ Kiørboe, Thomas (May 2011). "What makes pelagic copepods so successful? - Oxford Journals". Journal of Plankton Research. 33 (5): 677–685. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbq159. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ Bernot, J.; Boxshall, G.; Crandall, L. (August 18, 2021). "A synthesis tree of the Copepoda: integrating phylogenetic and taxonomic data reveals multiple origins of parasitism". PeerJ. 9 e12034. doi:10.7717/peerj.12034. PMC 8380027. PMID 34466296.

- ^ Johnson, Thomas D. (1987). Growth and regulation of a population of Parvocalanus crassirostris in Long Island, New York (Ph.D. Diss). SUNY Stony Brook. OCLC 19047124.

- ^ Kim, Ho-Young; Amauger, Juliette; Jeong, Han-Bi; Lee, Duck-Gyu; Yang, Eunjin; Jablonski, Piotr G. (2017-10-17). "Mechanics of jumping on water". Physical Review Fluids. 2 (10) 100505. American Physical Society (APS). Bibcode:2017PhRvF...2j0505K. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.2.100505. ISSN 2469-990X.

- ^ Bernot, James P.; Boxshall, Geoffrey A.; Crandall, Keith A. (2021-08-18). "A synthesis tree of the Copepoda: integrating phylogenetic and taxonomic data reveals multiple origins of parasitism". PeerJ. 9 e12034. doi:10.7717/peerj.12034. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8380027. PMID 34466296.

- ^ Johannes Dürbaum; Thorsten Künnemann (November 5, 1997). "Biology of Copepods: An Introduction". Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg. Archived from the original on May 26, 2010. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ "Biodiversity: Pity the copepod". The Economist. June 16, 2012. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ David W. Pond; Geraint A. Tarling (2011). "Phase transitions of wax esters adjust buoyancy in diapausing Calanoides acutus". Limnology and Oceanography. 56 (4): 1310–1318. Bibcode:2011LimOc..56.1310P. doi:10.4319/lo.2011.56.4.1310.

- ^ David W. Pond; Geraint A. Tarling (13 June 2011). "Copepods share "diver's weight belt" technique with whales". British Antarctic Survey. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ Bernot, J.; Boxshall, G.; Crandall, L. (August 18, 2021). "A synthesis tree of the Copepoda: integrating phylogenetic and taxonomic data reveals multiple origins of parasitism". PeerJ. 9 e12034. doi:10.7717/peerj.12034. PMC 8380027. PMID 34466296.

- ^ See photograph at "Blobfish / Psychrolutes microporos" (PDF). Census of Marine Life / NIWA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 16, 2008. Retrieved December 9, 2007. Photograph taken by Kerryn Parkinson and Robin McPhee in June 2003.

- ^ Bernot, J.; Boxshall, G.; Crandall, L. (August 18, 2021). "A synthesis tree of the Copepoda: integrating phylogenetic and taxonomic data reveals multiple origins of parasitism". PeerJ. 9 e12034. doi:10.7717/peerj.12034. PMC 8380027. PMID 34466296.

- ^ Boxshall, G.; Defaye, D. (2008). "Global diversity of copepods (Crustacea: Copepoda) in freshwater". Hydrobiologia. 595 (1): 195–207. Bibcode:2008HyBio.595..195B. doi:10.1007/s10750-007-9014-4. S2CID 31727589.

- ^ a b Edouard Chatton (1920). "Les Péridiniens parasites. Morphologie, reproduction, éthologie" (PDF). Arch. Zool. Exp. Gén. pp. 59, 1–475. plates I–XVIII. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-05-04. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- ^ a b c Skovgaard, Alf; Karpov, Sergey A.; Guillou, Laure (2012). "The Parasitic Dinoflagellates Blastodinium spp. Inhabiting the Gut of Marine, Planktonic Copepods: Morphology, Ecology, and Unrecognized Species Diversity". Front. Microbiol. 3 (305): 305. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00305. PMC 3428600. PMID 22973263.

- ^ a b Fields, D.M.; Runge, J.A.; Thompson, C.; Shema, S.D.; Bjelland, R.M.; Durif, C.M.F.; Skiftesvik, A.B.; Browman, H.I. (2014). "Infection of the planktonic copepod Calanus finmarchicus by the parasitic dinoflagellate, Blastodinium spp.: effects on grazing, respiration, fecundity and fecal pellet production". J. Plankton Res. 37: 211–220. doi:10.1093/plankt/fbu084.

- ^ Alves-de-Souza, Catharina; Cornet, C; Nowaczyk, A; Gasparini, Stéphane; Skovgaard, Alf; Guillou, Laure (2011). "Blastodinium spp. infect copepods in the ultra-oligotrophic marine waters of the Mediterranean Sea" (PDF). Biogeosciences. 8 (2): 2125–2136. Bibcode:2011BGeo....8.2125A. doi:10.5194/bgd-8-2563-2011.

- ^ Niehoff, Barbara (2000). "Effect of starvation on the reproductive potential of Calanus finmarchicus". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 57 (6): 1764–1772. Bibcode:2000ICJMS..57.1764N. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2000.0971.

- ^ "This Species is Close to Extinction and That's a Good Thing". Time. January 23, 2015. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- ^ Erken, Martina (May 29, 2015). "Interactions of Vibrio spp. with Zooplankton". Microbiology Spectrum. 3 (3) 3.3.02. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.ve-0003-2014. hdl:10220/46401. PMID 26185068.

- ^ Huq, Anwarul; et al. (July 15, 1982). "Ecological Relationships Between Vibrio cholerae and Planktonic Crustacean Copepods". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 45 (1): 275–283. doi:10.1128/aem.45.1.275-283.1983. PMC 242265. PMID 6337551.

- ^ Ho, Ju-shey; Perkins, Penny (1985). "Symbionts of Marine Copepoda: an Overview". Bulletin of Marine Science. 37 (2): 586–598.

- ^ Selden, Paul A.; Huys, Rony; Stephenson, Michael H.; Heward, Alan P.; Taylor, Paul N. (2010-08-10). "Crustaceans from bitumen clast in Carboniferous glacial diamictite extend fossil record of copepods". Nature Communications. 1 (1): 50. Bibcode:2010NatCo...1...50S. doi:10.1038/ncomms1049. hdl:1808/26575. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 20975721.

- ^ Harvey, Thomas H. P.; Vélez, Maria I.; Butterfield, Nicholas J. (2012-01-17). "Exceptionally preserved crustaceans from western Canada reveal a cryptic Cambrian radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (5): 1589–1594. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.1589H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115244109. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3277126. PMID 22307616.

- ^ HARVEY, T. H. P.; PEDDER, B. E. (2013-05-01). "Copepod Mandible Palynomorphs from the Nolichucky Shale (Cambrian, Tennessee): Implications for the Taphonomy and Recovery of Small Carbonaceous Fossils". PALAIOS. 28 (5): 278–284. Bibcode:2013Palai..28..278H. doi:10.2110/palo.2012.p12-124r. ISSN 0883-1351. S2CID 128694987.

- ^ Bernot, James P.; Boxshall, Geoffrey A.; Crandall, Keith A. (2021-08-18). "A synthesis tree of the Copepoda: integrating phylogenetic and taxonomic data reveals multiple origins of parasitism". PeerJ. 9 e12034. doi:10.7717/peerj.12034. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 8380027. PMID 34466296.

- ^ a b Drink Up NYC: Meet The Tiny Crustaceans (Not Kosher) In Your Tap Water . Time, September 2010, Allie Townsend.

- ^ Anthony DePalma (July 20, 2006). "New York's water supply may need filtering". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Ramamurthy, T.; Bhattacharya, S. K. (2011). Epidemiological and Molecular Aspects on Cholera. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-60327-265-0.

- ^ Vu Sinh Nam; Nguyen Thi Yen; Tran Vu Pong; Truong Uyen Ninh; Le Quyen Mai; Le Viet Lo; Le Trung Nghia; Ahmet Bektas; Alistair Briscombe; John G. Aaskov; Peter A. Ryan & Brian H. Kay (1 January 2005). "Elimination of dengue by community programs using Mesocyclops (Copepoda) against Aedes aegypti in central Vietnam". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 72 (1): 67–73. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.67. PMID 15728869.

- ^ G. G. Marten; J. W. Reid (2007). "Cyclopoid copepods". Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 23 (2 Suppl): 65–92. doi:10.2987/8756-971X(2007)23[65:CC]2.0.CO;2. PMID 17853599. S2CID 7645668.

- ^ "OU Fact Sheet on NYC Water". Orthodox Union Kosher Certification. New York City: Orthodox Union. August 13, 2004. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ Berger, Joseph (November 7, 2004) "The Water's Fine, But Is It Kosher?" Archived 2017-08-18 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ Bleich, Judah David (February 2, 2012). "Chapter 7 New York City Water". Contemporary Halachic problems, Vol. 6. ISBN 978-1-60280-195-0.

- ^ "NYC Tap Water Kosher Questions? OU Kosher Certification FAQs". OU Kosher Certification. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ "Hot Off the Hotline | STAR-K Kosher Certification". www.star-k.org. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ Wilson, Amy (February 12, 2002). "Stephen Hillenburg created the undersea world of SpongeBob". Orange County Register. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014.