Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

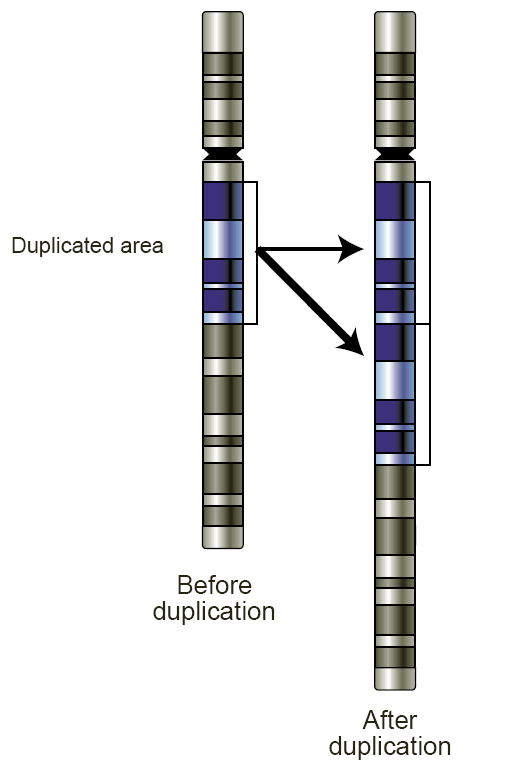

Copy number variation

View on Wikipedia

Copy number variation (CNV) is a phenomenon in which sections of the genome are repeated and the number of repeats in the genome varies between individuals.[1] Copy number variation is a type of structural variation: specifically, it is a type of duplication or deletion event that affects a considerable number of base pairs.[2] Approximately two-thirds of the entire human genome may be composed of repeats[3] and 4.8–9.5% of the human genome can be classified as copy number variations.[4] In mammals, copy number variations play an important role in generating necessary variation in the population as well as disease phenotype.[1]

Copy number variations can be generally categorized into two main groups: short repeats and long repeats. However, there are no clear boundaries between the two groups and the classification depends on the nature of the loci of interest. Short repeats include mainly dinucleotide repeats (two repeating nucleotides e.g. A-C-A-C-A-C...) and trinucleotide repeats. Long repeats include repeats of entire genes. This classification based on size of the repeat is the most obvious type of classification as size is an important factor in examining the types of mechanisms that most likely gave rise to the repeats,[5] hence the likely effects of these repeats on phenotype.

Types and chromosomal rearrangements

[edit]One of the most well known examples of a short copy number variation is the trinucleotide repeat of the CAG base pairs in the huntingtin gene responsible for the neurological disorder Huntington's disease.[6] For this particular case, once the CAG trinucleotide repeats more than 36 times in a trinucleotide repeat expansion, Huntington's disease will likely develop in the individual and it will likely be inherited by his or her offspring.[6] The number of repeats of the CAG trinucleotide is inversely correlated with the age of onset of Huntington's disease.[7] These types of short repeats are often thought to be due to errors in polymerase activity during replication including polymerase slippage, template switching, and fork switching which will be discussed in detail later. The short repeat size of these copy number variations lends itself to errors in the polymerase as these repeated regions are prone to misrecognition by the polymerase and replicated regions may be replicated again, leading to extra copies of the repeat.[8] In addition, if these trinucleotide repeats are in the same reading frame in the coding portion of a gene, it may lead to a long chain of the same amino acid, possibly creating protein aggregates in the cell,[7] and if these short repeats fall into the non-coding portion of the gene, it may affect gene expression and regulation. On the other hand, a variable number of repeats of entire genes is less commonly identified in the genome. One example of a whole gene repeat is the alpha-amylase 1 gene (AMY1) that encodes alpha-amylase which has a significant copy number variation between different populations with different diets.[9] Although the specific mechanism that allows the AMY1 gene to increase or decrease its copy number is still a topic of debate, some hypotheses suggest that the non-homologous end joining or the microhomology-mediated end joining is likely responsible for these whole gene repeats.[9] Repeats of entire genes has immediate effects on expression of that particular gene, and the fact that the copy number variation of the AMY1 gene has been related to diet is a remarkable example of recent human evolutionary adaptation.[9] Although these are the general groups that copy number variations are grouped into, the exact number of base pairs copy number variations affect depends on the specific loci of interest. Currently, using data from all reported copy number variations, the mean size of copy number variant is around 118kb, and the median is around 18kb.[10]

In terms of the structural architecture of copy number variations, research has suggested and defined hotspot regions in the genome where copy number variations are four times more enriched.[2] These hotspot regions were defined to be regions containing long repeats that are 90–100% similar known as segmental duplications either tandem or interspersed and most importantly, these hotspot regions have an increased rate of chromosomal rearrangement.[2] It was thought that these large-scale chromosomal rearrangements give rise to normal variation and genetic diseases, including copy number variations.[1] Moreover, these copy number variation hotspots are consistent throughout many populations from different continents, implying that these hotspots were either independently acquired by all the populations and passed on through generations, or they were acquired in early human evolution before the populations split, the latter seems more likely.[1] Lastly, spatial biases of the location at which copy number variations are most densely distributed does not seem to occur in the genome.[1] Although it was originally detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization and microsatellite analysis that copy number repeats are localized to regions that are highly repetitive such as telomeres, centromeres, and heterochromatin,[11] recent genome-wide studies have concluded otherwise.[2] Namely, the subtelomeric regions and pericentromeric regions are where most chromosomal rearrangement hotspots are found, and there is no considerable increase in copy number variations in that region.[2] Furthermore, these regions of chromosomal rearrangement hotspots do not have decreased gene numbers, again, implying that there is minimal spatial bias of the genomic location of copy number variations.[2]

Detection and identification

[edit]Copy number variation was initially thought to occupy an extremely small and negligible portion of the genome through cytogenetic observations.[12] Copy number variations were generally associated only with small tandem repeats or specific genetic disorders,[13] therefore, copy number variations were initially only examined in terms of specific loci. However, technological developments led to an increasing number of highly accurate ways of identifying and studying copy number variations. Copy number variations were originally studied by cytogenetic techniques, which are techniques that allow one to observe the physical structure of the chromosome.[12] One of these techniques is fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) which involves inserting fluorescent probes that require a high degree of complementarity in the genome for binding.[10] Comparative genomic hybridization was also commonly used to detect copy number variations by fluorophore visualization and then comparing the length of the chromosomes.[10]

Recent advances in genomics technologies gave rise to many important methods that are of extremely high genomic resolution and as a result, an increasing number of copy number variations in the genome have been reported.[10] Initially these advances involved using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) array with around 1 megabase of intervals throughout the entire gene,[14] BACs can also detect copy number variations in rearrangement hotspots allowing for the detection of 119 novel copy number variations.[2] High throughput genomic sequencing has revolutionized the field of human genomics and in silico studies have been performed to detect copy number variations in the genome.[2] Reference sequences have been compared to other sequences of interest using fosmids by strictly controlling the fosmid clones to be 40kb.[15] Sequencing end reads would provide adequate information to align the reference sequence to the sequence of interest, and any misalignments are easily noticeable thus concluded to be copy number variations within that region of the clone.[15] This type of detection technique offers a high genomic resolution and precise location of the repeat in the genome, and it can also detect other types of structural variation such as inversions.[10]

In addition, another way of detecting copy number variation is using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).[10] Due to the abundance of the human SNP data, the direction of detecting copy number variation has changed to utilize these SNPs.[16] Relying on the fact that human recombination is relatively rare and that many recombination events occur in specific regions of the genome known as recombination hotspots, linkage disequilibrium can be used to identify copy number variations.[16] Efforts have been made in associating copy number variations with specific haplotype SNPs by analyzing the linkage disequilibrium, using these associations, one is able to recognize copy number variations in the genome using SNPs as markers. Next-generation sequencing techniques including short and long read sequencing are nowadays increasingly used and have begun to replace array-based techniques to detect copy number variations.[17][18]

Molecular mechanism

[edit]There are two main types of molecular mechanism for the formation of copy number variations: homologous based and non-homologous based.[5] Although many suggestions have been put forward, most of these theories are speculations and conjecture. There is no conclusive evidence that correlates a specific copy number variation to a specific mechanism.

One of the best-recognized theories that leads to copy number variations as well as deletions and inversions is non-allelic homologous recombinations.[19] During meiotic recombination, homologous chromosomes pair up and form two ended double-stranded breaks leading to Holliday junctions. However, in the aberrant mechanism, during the formation of Holliday junctions, the double-stranded breaks are misaligned and the crossover lands in non-allelic positions on the same chromosome. When the Holliday junction is resolved, the unequal crossing over event allows transfer of genetic material between the two homologous chromosomes, and as a result, a portion of the DNA on both the homologues is repeated.[19] Since the repeated regions are no longer segregating independently, the duplicated region of the chromosome is inherited. Another type of homologous recombination based mechanism that can lead to copy number variation is known as break induced replication.[20] When a double stranded break occurs in the genome unexpectedly the cell activates pathways that mediate the repair of the break.[20] Errors in repairing the break, similar to non-allelic homologous recombination, can lead to an increase in copy number of a particular region of the genome. During the repair of a double stranded break, the broken end can invade its homologous chromosome instead of rejoining the original strand.[20] As in the non-allelic homologous recombination mechanism, an extra copy of a particular region is transferred to another chromosome, leading to a duplication event. Furthermore, cohesin proteins are found to aid in the repair system of double stranded breaks through clamping the two ends in close proximity which prevents interchromosomal invasion of the ends.[21] If for any reason, such as activation of ribosomal RNA, cohesin activity is affected then there may be local increase in double stranded break repair errors.[21]

The other class of possible mechanisms that are hypothesized to lead to copy number variations is non-homologous based. To distinguish between this and homologous based mechanisms, one must understand the concept of homology. Homologous pairing of chromosomes involved using DNA strands that are highly similar to each other (~97%) and these strands must be longer than a certain length to avoid short but highly similar pairings.[5] Non-homologous pairings, on the other hand, rely on only few base pairs of similarity between two strands, therefore it is possible for genetic materials to be exchanged or duplicated in the process of non-homologous based double stranded repairs.[5]

One type of non-homologous based mechanism is the non-homologous end joining or micro-homology end joining mechanism.[22] These mechanisms are also involved in repairing double stranded breaks but require no homology or limited micro-homology.[5] When these strands are repaired, oftentimes there are small deletions or insertions added into the repaired strand. It is possible that retrotransposons are inserted into the genome through this repair system.[22] If retrotransposons are inserted into a non-allelic position on the chromosome, meiotic recombination can drive the insertion to be recombined into the same strand as an already existing copy of the same region. Another mechanism is the break-fusion-bridge cycle which involves sister chromatids that have both lost its telomeric region due to double stranded breaks.[23] It is proposed that these sister chromatids will fuse together to form one dicentric chromosome, and then segregate into two different nuclei.[23] Because pulling the dicentric chromosome apart causes a double stranded break, the end regions can fuse to other double stranded breaks and repeat the cycle.[23] The fusion of two sister chromatids can cause inverted duplication and when these events are repeated throughout the cycle, the inverted region will be repeated leading to an increase in copy number.[23] The last mechanism that can lead to copy number variations is polymerase slippage, which is also known as template switching.[24] During normal DNA replication, the polymerase on the lagging strand is required to unclamp and re-clamp the replication region continuously.[24] When small scale repeats in the DNA sequence exist already, the polymerase can be 'confused' when it re-clamps to continue replication and instead of clamping to the correct base pairs, it may shift a few base pairs and replicate a portion of the repeated region again.[24] Note that although this has been experimentally observed and is a widely accepted mechanism, the molecular interactions that led to this error remains unknown. In addition, because this type of mechanism requires the polymerase to jump around the DNA strand and it is unlikely that the polymerase can re-clamp at another locus some kilobases apart, therefore this is more applicable to short repeats such as dinucleotide or trinucleotide repeats.[25]

Alpha-amylase gene

[edit]

Amylase is an enzyme in saliva that is responsible for the breakdown of starch into monosaccharides, and one type of amylase is encoded by the alpha-amylase gene (AMY1).[9] The AMY1 locus, as well as the amylase enzyme, is one of the most extensively studied and sequenced genes in the human genome. Its homologs are also found in other primates and therefore it is likely that the primate AMY1 gene is ancestral to the human AMY1 gene and was adapted early in primate evolution.[9] AMY1 is one of the most well studied genes which has wide range of variable numbers of copies throughout different human populations.[9] The AMY1 gene is also one of the few genes that had been studied that displayed convincing evidence which correlates its protein function to its copy number.[9] Copy number is known to alter transcription as well as translation levels of a particular gene, however research has shown that the relationship between protein levels and copy number is variable.[26] In the AMY1 genes of European Americans it is found that the concentration of salivary amylase is closely correlated to the copy number of the AMY1 gene.[9] As a result, it was hypothesized that the copy number of the AMY1 gene is closely correlated with its protein function, which is to digest starch.[9]

The AMY1 gene copy number has been found to be correlated to different levels of starch in diets of different populations.[9] Eight populations from different continents were categorized into high starch diets and low starch diets and their AMY1 gene copy number was visualized using high resolution FISH and qPCR.[9] It was found that the high starch diet populations which consists of the Japanese, Hadza, and European American populations had a significantly higher (two times higher) average AMY1 copy number than the low starch diet populations including Biaka, Mbuti, Datog and Yakut populations.[9] It was hypothesized that the levels of starch in one's regular diet, the substrate for AMY1, can directly affect the copy number of the AMY1 gene.[9] Since it was concluded that the copy number of AMY1 is directly correlated with salivary amylase,[9] the more starch present in the population's daily diet, the more evolutionarily favorable it is to have multiple copies of the AMY1 gene. The AMY1 gene was the first gene to provide strong evidence for evolution on a molecular genetic level.[26] Moreover, using comparative genomic hybridization, copy number variations of the entire genomes of the Japanese population was compared to that of the Yakut population.[9] It was found that the copy number variation of the AMY1 gene was significantly different from the copy number variation in other genes or regions of the genome, suggesting that the AMY1 gene was under a strong selective pressure that had little or no influence on the other copy number variations.[9] Finally, the variability of length of 783 microsatellites between the two populations was compared to copy number variability of the AMY1 gene. It was found that the AMY1 gene copy number range was larger than that of over 97% of the microsatellites examined.[9] This implies that natural selection played a considerable role in shaping the average number of AMY1 genes in these two populations.[9] However, as only six populations were studied, it is important to consider the possibility that there may be other factors in their diet or culture that influenced the AMY1 copy number other than starch.

Although it is unclear when the AMY1 gene copy number began to increase, it is known and confirmed that the AMY1 gene existed in early primates. Chimpanzees, the closest evolutionary relatives to humans, were found to have two diploid copies of the AMY1 gene that is identical in length to the human AMY1 gene,[9] which is significantly less than that of humans. On the other hand, bonobos, also a close relative of modern humans, were found to have more than two diploid copies of the AMY1 gene.[9] Nonetheless, the bonobo AMY1 genes were sequenced and analyzed, and it was found that the coding sequences of the AMY1 genes were disrupted, which may lead to the production of dysfunctional salivary amylase.[9] It can be inferred from the results that the increase in bonobo AMY1 copy number is likely not correlated to the amount of starch in their diet. It was further hypothesized that the increase in copy number began recently during early hominin evolution as none of the great apes had more than two copies of the AMY1 gene that produced functional protein.[9] In addition, it was speculated that the increase in the AMY1 copy number began around 20,000 years ago when humans shifted from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to agricultural societies, which was also when humans relied heavily on root vegetables high in starch.[9] This hypothesis, although logical, lacks experimental evidence due to the difficulties in gathering information on the shift of human diets, especially on root vegetables that are high in starch as they cannot be directly observed or tested. Recent breakthroughs in DNA sequencing has allowed researchers to sequence older DNA such as that of Neanderthals to a certain degree of accuracy. Perhaps sequencing Neanderthal DNA can provide a time marker as to when the AMY1 gene copy number increased and offer insight into human diet and gene evolution.

Currently it is unknown which mechanism gave rise to the initial duplication of the amylase gene, and it can imply that the insertion of the retroviral sequences was due to non-homologous end joining, which caused the duplication of the AMY1 gene.[27] However, there is currently no evidence to support this theory and therefore this hypothesis remains conjecture. The recent origin of the multi-copy AMY1 gene implies that depending on the environment, the AMY1 gene copy number can increase and decrease very rapidly relative to genes that do not interact as directly with the environment.[26] The AMY1 gene is an excellent example of how gene dosage affects the survival of an organism in a given environment. The multiple copies of the AMY1 gene give those who rely more heavily on high starch diets an evolutionary advantage, therefore the high gene copy number persists in the population.[26]

Brain cells

[edit]Among the neurons in the human brain, somatically derived copy number variations are frequent.[28] Copy number variations show wide variability (9 to 100% of brain neurons in different studies). Most alterations are between 2 and 10 Mb in size with deletions far outnumbering amplifications.[28]

Genomic duplication and triplication of the gene appear to be a rare cause of Parkinson's disease, although more common than point mutations.[29]

Copy number variants in RCL1 gene are associated with a range of neuropsychiatric phenotypes in children.[30]

Gene families and natural selection

[edit]

Recently, there had been discussion connecting copy number variations to gene families. Gene families are defined as a set of related genes that serve similar functions but have minor temporal or spatial differences and these genes likely derived from one ancestral gene.[26] The main reason copy number variations are connected to gene families is that there is a possibility that genes in a family may have derived from one ancestral gene which got duplicated into different copies.[26] Mutations accumulate through time in the genes and with natural selection acting on the genes, some mutations lead to environmental advantages allowing those genes to be inherited and eventually clear gene families are separated out. An example of a gene family that may have been created due to copy number variations is the globin gene family. The globin gene family is an elaborate network of genes consisting of alpha and beta globin genes including genes that are expressed in both embryos and adults as well as pseudogenes.[31] These globin genes in the globin family are all well conserved and only differ by a small portion of the gene, indicating that they were derived from a common ancestral gene, perhaps due to duplication of the initial globin gene.[31]

Research has shown that copy number variations are significantly more common in genes that encode proteins that directly interact with the environment than proteins that are involved in basic cellular activities.[32] It was suggested that the gene dosage effect accompanying copy number variation may lead to detrimental effects if essential cellular functions are disrupted, therefore proteins involved in cellular pathways are subjected to strong purifying selection.[32] In addition, proteins function together and interact with proteins of other pathways, therefore it is important to view the effects of natural selection on bio-molecular pathways rather than on individual proteins. With that being said, it was found that proteins in the periphery of the pathway are enriched in copy number variations whereas proteins in the center of the pathways are depleted in copy number variations.[33] It was explained that proteins in the periphery of the pathway interact with fewer proteins and so a change in protein dosage affected by a change in copy number may have a smaller effect on the overall outcome of the cellular pathway.[33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e McCarroll SA, Altshuler DM (July 2007). "Copy-number variation and association studies of human disease". Nature Genetics. 39 (7 Suppl): S37-42. doi:10.1038/ng2080. PMID 17597780. S2CID 8521333.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sharp AJ, Locke DP, McGrath SD, Cheng Z, Bailey JA, Vallente RU, et al. (July 2005). "Segmental duplications and copy-number variation in the human genome". American Journal of Human Genetics. 77 (1): 78–88. doi:10.1086/431652. PMC 1226196. PMID 15918152.

- ^ de Koning AP, Gu W, Castoe TA, Batzer MA, Pollock DD (December 2011). "Repetitive elements may comprise over two-thirds of the human genome". PLOS Genetics. 7 (12) e1002384. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002384. PMC 3228813. PMID 22144907.

- ^ Zarrei M, MacDonald JR, Merico D, Scherer SW (March 2015). "A copy number variation map of the human genome". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 16 (3): 172–83. doi:10.1038/nrg3871. hdl:2027.42/146425. PMID 25645873. S2CID 19697843.

- ^ a b c d e Hastings PJ, Lupski JR, Rosenberg SM, Ira G (August 2009). "Mechanisms of change in gene copy number". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 10 (8): 551–64. doi:10.1038/nrg2593. PMC 2864001. PMID 19597530.

- ^ a b "A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington's disease chromosomes. The Huntington's Disease Collaborative Research Group" (PDF). Cell. 72 (6): 971–83. March 1993. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. hdl:2027.42/30901. PMID 8458085. S2CID 802885.

- ^ a b Myers RH (April 2004). "Huntington's disease genetics". NeuroRx. 1 (2): 255–62. doi:10.1602/neurorx.1.2.255. PMC 534940. PMID 15717026.

- ^ Albertini AM, Hofer M, Calos MP, Miller JH (June 1982). "On the formation of spontaneous deletions: the importance of short sequence homologies in the generation of large deletions". Cell. 29 (2): 319–28. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90148-9. PMID 6288254. S2CID 36657944.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Perry GH, Dominy NJ, Claw KG, Lee AS, Fiegler H, Redon R, et al. (October 2007). "Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation". Nature Genetics. 39 (10): 1256–60. doi:10.1038/ng2123. PMC 2377015. PMID 17828263.

- ^ a b c d e f Freeman JL, Perry GH, Feuk L, Redon R, McCarroll SA, Altshuler DM, et al. (August 2006). "Copy number variation: new insights in genome diversity". Genome Research. 16 (8): 949–61. doi:10.1101/gr.3677206. PMID 16809666.

- ^ Bailey JA, Gu Z, Clark RA, Reinert K, Samonte RV, Schwartz S, et al. (August 2002). "Recent segmental duplications in the human genome". Science. 297 (5583): 1003–7. Bibcode:2002Sci...297.1003B. doi:10.1126/science.1072047. PMID 12169732. S2CID 16501865.

- ^ a b Jacobs PA, Browne C, Gregson N, Joyce C, White H (February 1992). "Estimates of the frequency of chromosome abnormalities detectable in unselected newborns using moderate levels of banding". Journal of Medical Genetics. 29 (2): 103–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.29.2.103. PMC 1015848. PMID 1613759.

- ^ Inoue K, Lupski JR (2002). "Molecular mechanisms for genomic disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 3: 199–242. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.3.032802.120023. PMID 12142364.

- ^ Iafrate AJ, Feuk L, Rivera MN, Listewnik ML, Donahoe PK, Qi Y, et al. (September 2004). "Detection of large-scale variation in the human genome". Nature Genetics. 36 (9): 949–51. doi:10.1038/ng1416. PMID 15286789.

- ^ a b Tuzun E, Sharp AJ, Bailey JA, Kaul R, Morrison VA, Pertz LM, et al. (July 2005). "Fine-scale structural variation of the human genome". Nature Genetics. 37 (7): 727–32. doi:10.1038/ng1562. PMID 15895083. S2CID 14162962.

- ^ a b Conrad B, Antonarakis SE (2007). "Gene duplication: a drive for phenotypic diversity and cause of human disease". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 8: 17–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.genom.8.021307.110233. PMID 17386002.

- ^ Alkan C, Coe BP, Eichler EE (May 2011). "Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 12 (5): 363–76. doi:10.1038/nrg2958. PMC 4108431. PMID 21358748.

- ^ Sudmant PH, Rausch T, Gardner EJ, Handsaker RE, Abyzov A, Huddleston J, et al. (October 2015). "An integrated map of structural variation in 2,504 human genomes". Nature. 526 (7571): 75–81. Bibcode:2015Natur.526...75.. doi:10.1038/nature15394. PMC 4617611. PMID 26432246.

- ^ a b Pâques F, Haber JE (June 1999). "Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (2): 349–404. doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.2.349-404.1999. PMC 98970. PMID 10357855.

- ^ a b c Bauters M, Van Esch H, Friez MJ, Boespflug-Tanguy O, Zenker M, Vianna-Morgante AM, et al. (June 2008). "Nonrecurrent MECP2 duplications mediated by genomic architecture-driven DNA breaks and break-induced replication repair". Genome Research. 18 (6): 847–58. doi:10.1101/gr.075903.107. PMC 2413152. PMID 18385275.

- ^ a b Kobayashi T, Ganley AR (September 2005). "Recombination regulation by transcription-induced cohesin dissociation in rDNA repeats". Science. 309 (5740): 1581–4. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.1581K. doi:10.1126/science.1116102. PMID 16141077. S2CID 21547462.

- ^ a b Lieber MR (January 2008). "The mechanism of human nonhomologous DNA end joining". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.R700039200. PMID 17999957.

- ^ a b c d McCLINTOCK B (1951). "Chromosome organization and genic expression". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 16: 13–47. doi:10.1101/sqb.1951.016.01.004. PMID 14942727.

- ^ a b c Smith CE, Llorente B, Symington LS (May 2007). "Template switching during break-induced replication". Nature. 447 (7140): 102–5. Bibcode:2007Natur.447..102S. doi:10.1038/nature05723. PMID 17410126. S2CID 7427921.

- ^ Bi X, Liu LF (January 1994). "recA-independent and recA-dependent intramolecular plasmid recombination. Differential homology requirement and distance effect". Journal of Molecular Biology. 235 (2): 414–23. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1002. PMID 8289271.

- ^ a b c d e f Korbel JO, Kim PM, Chen X, Urban AE, Weissman S, Snyder M, Gerstein MB (June 2008). "The current excitement about copy-number variation: how it relates to gene duplications and protein families". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 18 (3): 366–74. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.005. PMC 2577873. PMID 18511261.

- ^ Samuelson LC, Wiebauer K, Snow CM, Meisler MH (June 1990). "Retroviral and pseudogene insertion sites reveal the lineage of human salivary and pancreatic amylase genes from a single gene during primate evolution". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 10 (6): 2513–20. doi:10.1128/mcb.10.6.2513. PMC 360608. PMID 1692956.

- ^ a b Rohrback S, Siddoway B, Liu CS, Chun J (November 2018). "Genomic mosaicism in the developing and adult brain". Developmental Neurobiology. 78 (11): 1026–1048. doi:10.1002/dneu.22626. PMC 6214721. PMID 30027562.

- ^ Singleton AB, Farrer M, Johnson J, Singleton A, Hague S, Kachergus J, et al. (October 2003). "alpha-Synuclein locus triplication causes Parkinson's disease". Science. 302 (5646): 841. doi:10.1126/science.1090278. PMID 14593171. S2CID 85938327.

- ^ Brownstein, CA; Smith, RS; Rodan, LH; Gorman, MP; Hojlo, MA; Garvey, EA; Li, J; Cabral, K; Bowen, JJ; Rao, AS; Genetti, CA; Carroll, D; Deaso, EA; Agrawal, PB; Rosenfeld, JA; Bi, W; Howe, J; Stavropoulos, DJ; Hansen, AW; Hamoda, HM; Pinard, F; Caracansi, A; Walsh, CA; D'Angelo, EJ; Beggs, AH; Zarrei, M; Gibbs, RA; Scherer, SW; Glahn, DC; Gonzalez-Heydrich, J (17 February 2021). "RCL1 copy number variants are associated with a range of neuropsychiatric phenotypes". Molecular Psychiatry. 26 (5): 1706–1718. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01035-y. PMC 8159744. PMID 33597717.

- ^ a b Goodman M, Koop BF, Czelusniak J, Weiss ML (December 1984). "The eta-globin gene. Its long evolutionary history in the beta-globin gene family of mammals". Journal of Molecular Biology. 180 (4): 803–23. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90258-4. PMID 6527390.

- ^ a b Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, et al. (November 2006). "Global variation in copy number in the human genome". Nature. 444 (7118): 444–54. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..444R. doi:10.1038/nature05329. PMC 2669898. PMID 17122850.

- ^ a b Kim PM, Korbel JO, Gerstein MB (December 2007). "Positive selection at the protein network periphery: evaluation in terms of structural constraints and cellular context". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (51): 20274–9. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10420274K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710183104. PMC 2154421. PMID 18077332.

Further reading

[edit]- Pollack JR, Perou CM, Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Pergamenschikov A, Williams CF, Jeffrey SS, Botstein D, Brown PO (September 1999). "Genome-wide analysis of DNA copy-number changes using cDNA microarrays". Nature Genetics. 23 (1): 41–6. doi:10.1038/12640. PMID 10471496. S2CID 997032.

- "Huge genetic variation in healthy people". New Scientist. 7 August 2004.

- Carter NP (September 2004). "As normal as normal can be?". Nature Genetics. 36 (9): 931–2. doi:10.1038/ng0904-931. PMID 15340426.

- Check E (October 2005). "Human genome: patchwork people". Nature. 437 (7062): 1084–6. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1084C. doi:10.1038/4371084a. PMID 16237414. S2CID 8211641.

- "Gene duplications may define who you are". New Scientist. 22 November 2006.

- "DNA varies more widely from person to person, Genetic maps reveal". National Geographic. 22 November 2006. Archived from the original on 25 November 2006.

- "Finding the right lenses" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 1 July 2007.

- Lam HY, Mu XJ, Stütz AM, Tanzer A, Cayting PD, Snyder M, et al. (January 2010). "Nucleotide-resolution analysis of structural variants using BreakSeq and a breakpoint library". Nature Biotechnology. 28 (1). Nature Biotechnoloty: 47–55. doi:10.1038/nbt.1600. PMC 2951730. PMID 20037582.

- "New Research Sheds Light on Autism's Genetic Causes". Singularity Hub. 15 June 2010. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

External links

[edit]- Copy Number Variation Project, Sanger Institute

- The Claim: Identical Twins Have Identical DNA

- Integrative annotation platform for copy number variations in humans

- A bibliography on copy number variation

- Database of Genomic Variants, a database of structural variants in the human genome

- Copy Number Variation Detection via High-Density SNP Genotyping

- Oxford Gene Technology

- BioDiscovery Nexus Copy Number

- High-resolution mapping of copy number variations in 2,026 healthy individuals

- IGSR: The International Genome Sample Resource

- cn.FARMS: a latent variable model to detect copy number variations in microarray data with a low false discovery rate, an R package—software

- cn.MOPS: mixture of Poissons for discovering copy number variations in next generation sequencing data—software