Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cossack cross

View on Wikipedia

The Cossack cross (Ukrainian: Козацький хрест, romanized: Kozatskyi khrest) is a type of the Templar cross used by the Ukrainian Ground Forces.[1][2][3][4] It is frequently used in Ukraine as a memorial sign to fallen soldiers[5][6][7][8] and as military awards.[3][9]

History

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Cossacks |

|---|

|

| Cossack hosts |

| Other Cossack groups |

| History |

| Notable Cossacks |

| Cossack terms |

| Cossack folklore |

| Notable people of Cossack descent |

Historically it was used by Cossacks, most prominently the Zaporozhian Host.

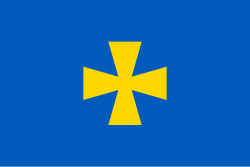

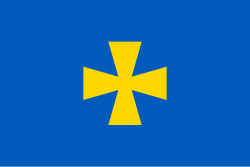

In modern times cross has been adapted as part of the emblem of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, the State Emergency Service of Ukraine, the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine and the Security Service of Ukraine, and is depicted on the flags and coat of arms of several Ukrainian regions, districts and cities, like Konotop, Zinkiv and Zolotonosha.[3][10][11] The Memorial to Ukrainians shot at Sandarmokh uses a Cossack cross.[12][13][8]

Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]As of September 2022 during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian forces started to paint a simplified white Cossack cross on their vehicles as an IFF marker designating Ukrainian vehicles from a distance.[14]

Examples

[edit]-

Flag of the Zaporozhian Sich

-

Emblem of the Ukrainian Armed Forces

-

Emblem of the State Border Guard Service of Ukraine

-

Security Service of Ukraine Emblem

-

State Service of Ukraine for Emergencies

-

The Badge of Honour

-

Medal For Supporting the Armed Forces of Ukraine

-

Flag of the former Bobrovytsia Raion with a Cossack cross under its coat-of-arms

-

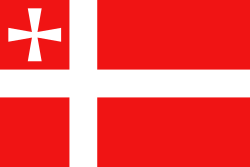

Flag of Azov (Russia) with a Cossack cross

-

Flag of Cetinje

-

Coat of arms of Rivne Oblast

-

Coat of arms of Konotop

-

Memorial at Sandarmokh

-

Cossack crosses seen at the Usatove cemetery

-

Plain Cossack cross

-

Ukrainian vehicle marking during the Russo-Ukrainian War

-

Ukrainian vehicle marking during the Russo-Ukrainian War

-

Soldier of the 17th Tank Brigade painting a cross on a captured tank

-

Cossack Crosses painted on a Valuk APC

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "У Харкові відкрили "Козацький хрест", присвячений загиблим на Донбасі". Укрінформ - актуальні новини України та світу (in Ukrainian). 3 December 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Козацький хрест в с.Аврамівка". Катеринівська сільська рада Кіровоградська область, Кропивницький район (in Ukrainian). 10 August 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "ПРЕЗИДЕНТ В СУМАХ ВІДКРИВ КОЗАЦЬКИЙ ХРЕСТ БОРЦЯМ ЗА ВОЛЮ УКРАЇНИ". vpr.sm.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). 22 July 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Стародавній козацький хрест повернеться в історичний центр Житомира. ВІДЕО". Журнал Житомира (in Ukrainian). 21 August 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Порошенко у Сумах відкрив Козацький хрест – Трибуна – новини Сум та Сумської області". Трибуна (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Naszą siłą jest jedność!". Monitor Wolynski (in Polish). 15 July 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Memorial cross to defenders of Ukraine unveiled in Kyiv". Religious Information Service of Ukraine. 14 October 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ a b Kozielski, Jan (September 2014). "W Sołowkach przy kamieniu pamięci…" [In Solovki, next to the memorial stone…] (PDF). Dziennik Kijowski (Дзеннік Кійовскі) (in Polish). Vol. 17, no. 480. Kyiv. p. 4. OCLC 749394789.

- ^ "Волонтерам від військових. Олену Куртяк відзначено нагородою – "Козацький хрест " III ступеню (ВІДЕО)". ВАРТО - Галицькі Новини (in Ukrainian). 19 December 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Krzemieniec - Karta Dziedzictwa Kulturowego - Teatr NN". Shtetl Routes (in Polish). Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ В.Г. Кисляк (2010). Україна: герби та прапори (in Ukrainian) (Парламентське вид-во ed.). О.А. Нескоромний. p. 456.

- ^ "A Cossack Cross in Sandarmokh". A Cossack Cross in Sandarmokh. 6 September 2005. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Coynash, Halya (28 January 2020). "Historian Yury Dmitriev imprisoned in Russia for insisting on Memory of the Soviet Terror and Sandarmokh". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "The backstory about the sense of the white cross used by the Ukrainian troops to mark their vehicles during the latest counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region". We Are Ukraine (in Ukrainian). 2022-09-21. Retrieved 2023-01-04.

- ^ "23 серпня - День державного прапора України: історія23 серпня - День державного прапора України: історія". Новини України - #Букви. 2020-08-23. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

External links

[edit] Media related to Category:Ukrainian Cossack crosses at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Category:Ukrainian Cossack crosses at Wikimedia Commons

Cossack cross

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Context

Etymology and Early Symbolism

The Cossack cross, a variant of the heraldic cross pattée characterized by arms that widen toward their ends and often terminate in a wedge or V-shape, acquired its designation from its adoption by Cossack hosts, particularly the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who employed it in military banners, seals, and commemorative markers from the 16th century onward.[5] This form of cross, resembling the Maltese cross in some renderings, symbolized the fusion of martial prowess and Orthodox Christian piety central to Cossack identity, with the broadening arms evoking resilience and territorial defense against steppe incursions.[6] Etymologically, the term "Cossack cross" emerged in Imperial Russian contexts by the 19th century to denote this specific pattée style linked to Cossack burial and regimental traditions, distinguishing it from other Christian crosses despite shared medieval origins traceable to European military orders.[6] Early exemplars, such as limestone grave markers dated July 26, 1816, in the Spasskoye cemetery (Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine), illustrate its use in commemorating individuals of probable Cossack-Doukhobor descent, underscoring a symbolism of eternal life and communal endurance amid persecution and exile.[6] In its nascent symbolism among Cossacks, the cross represented divine protection for frontier warriors, drawing on broader Eastern Christian motifs of victory over death—akin to catacomb crosses of early Christianity—while serving as a rallying emblem in 17th-century uprisings, such as those led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, where it appeared on hetman standards denoting faith-fueled resistance.[7] The design's geometric stability also connoted the Cossacks' self-governing Sich structures, embedding principles of hierarchy and solidarity rooted in Orthodox theology rather than feudal allegiance.[8]Adoption by Cossack Communities

The Cossack cross emerged as a prominent symbol among Cossack communities during the 16th to 18th centuries, particularly within the Zaporozhian Host, where it represented Orthodox Christian devotion and military resolve amid conflicts with the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[9] Historical evidence from Cossack military standards demonstrates early adoption, with crosses appearing on regimental flags as early as the 17th century; for instance, in 1626, the Starodub Cossack Troop utilized a red flag featuring a blue cross, while the Chernihiv Cossack Troop employed a blue flag with a red cross.[3] These designs underscored the Cossacks' self-conception as frontier guardians of faith, integrating heraldic crosses into banners that accompanied raids and defensive campaigns. The specific variant known as the Cossack cross—a cross pattée with wedge-shaped terminations—integrated into the heraldry of Cossack elites, including noble families like the Kotchoubeys, whose arms incorporated golden cross pattée elements symbolizing loyalty and valor.[10] This adoption reflected the Cossacks' Orthodox identity, distinguishing their symbols from Latin or Byzantine crosses prevalent in rival polities, and served practical purposes in unit identification during the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1657) and subsequent hetmanates. Seals and standards from the Zaporozhian Sich era further attest to crosses as emblems of communal oaths and martial honor, though primary sources emphasize functional crosses over stylized variants until later codification.[3] Following the Russian Empire's dissolution of the Zaporozhian Sich in 1775, the symbol persisted in diaspora Cossack groups and revived traditions, maintaining continuity in regimental insignias and commemorative iconography.[4] Its use in these contexts prioritized empirical markers of heritage over ideological reinterpretation, with archaeological and archival records from Cossack settlements confirming cross motifs on gravestones and artifacts dating to the hetmanate period.[11]Design and Variants

Geometric Features

The Cossack cross features four equal-length arms extending symmetrically from a central intersection point, exhibiting four-fold rotational symmetry. Each arm is narrowest at the center, where it meets the intersection, and flares outward with straight or slightly concave sides to form a wedge-shaped profile that terminates in a pointed tip, creating an overall star-like silhouette.[8] This design distinguishes it as a specialized form of the cross pattée, where the expansion emphasizes angular, tapered extremities rather than blunt or rounded ends.[9] In heraldic representations, the cross is typically rendered as couped, with arms that do not reach the edges of the enclosing field, allowing for precise scaling in emblems, flags, and memorials. The wedge-like tapering of the arms enhances visual sharpness and proportionality, often with the angle of flare approximating 45 degrees from the central axis, though exact measurements vary by artistic or institutional rendition.[12] Variants may include minor stylizations, such as subtle curvatures or added serifs, but the core geometric integrity remains defined by the pointed, expanding limbs.[8]Comparison to Other Cross Types

The Cossack cross features four equilateral arms that narrow at the center and broaden outward into wedge-shaped expansions, distinguishing it from the Latin cross, which has a longer vertical shaft and shorter horizontal crossbar to represent the instrument of Christ's crucifixion.[8] This equilateral structure aligns it more closely with the Greek cross, a basic form with arms of equal length and uniform width, though the Cossack variant's pattée widening adds a heraldic flair absent in the plain Greek design.[13] In heraldic terms, the Cossack cross resembles the cross pattée, where arms flare from a narrow base to wider ends, but its specific wedge-like taper—forming isosceles triangular segments—sets it apart from the more gently curved or straight-edged broadening typical of standard pattée forms used in Western European coats of arms.[14] Unlike the cross potent, which terminates in crutch-like or T-shaped projections evoking pommels, the Cossack cross maintains a pointed, streamlined expansion without such protrusions, emphasizing simplicity suited to military banners.[15] The cross fleury, adorned with fleur-de-lis or trefoil motifs at the arm ends to symbolize floral or divine embellishment, contrasts sharply with the unadorned, geometric severity of the Cossack cross, which prioritizes bold visibility over ornamental detail in Cossack regimental flags dating back to the 17th century.[16] Similarly, while the Byzantine cross often incorporates multiple horizontal bars—including a slanted lower beam for the footrest in Orthodox iconography—the Cossack cross adheres to a single-barred, equilateral profile, reflecting its adaptation for secular and martial heraldry rather than strictly liturgical use.[17] This form also differentiates it from the Maltese cross, known for its V-notched arms forming eight points, a design tied to the Knights Hospitaller rather than Eastern steppe warrior traditions.[18]Cultural and Religious Significance

Ties to Eastern Orthodox Christianity

The Cossack cross maintains ties to Eastern Orthodox Christianity through its adoption by Cossack communities historically devoted to the faith as defenders against non-Orthodox powers. In the early modern period, Cossacks positioned themselves as protectors of Orthodoxy amid encounters with Islam, Catholicism, and other confessions in the steppe frontiers. This allegiance influenced the integration of Christian crosses into Cossack symbolism, with Orthodoxy guiding rites from baptism to burial. Contemporary Cossack groups continue to employ the Cossack cross in explicitly Orthodox settings, such as worship crosses erected on religious holidays. On January 7, 2025—Orthodox Christmas Day—a Cossack worship cross was raised in occupied Donetsk oblast by the All-Russian Cossack Society, its ataman Vitaly Kuznetsov stating it represented "faith and victory" amid ongoing conflict.[19] Similarly, Russia-backed Cossack fighters have sworn oaths incorporating the symbol within Moscow Patriarchate churches, affirming loyalty to Orthodox principles alongside military service.[20] While not a distinct liturgical emblem in Orthodox canon, the Cossack cross appears in commemorative sites linked to Orthodox martyrdom and memory, including memorials for victims of Soviet repressions where Christian crosses predominate.[6] Its wedge-shaped pattée form aligns with heraldic traditions in Orthodox-influenced regions, symbolizing resilience and divine protection in Cossack religious narratives.[8]Role in Cossack Identity and Folklore

The Cossack cross functions as a core emblem in Cossack identity, encapsulating their historical role as autonomous Orthodox Christian warriors dedicated to safeguarding eastern frontiers against invasions. Rooted in the traditions of groups like the Zaporozhian Sich, it signifies unyielding defense of faith, homeland, and personal liberty, traits central to the Cossack self-conception as free elect communities (volni hromady).[21] This symbolism underscores the Cossacks' corporate ideology, where heraldic motifs reinforced group cohesion and knightly aspirations amid 16th- to 18th-century steppe conflicts.[22] In Cossack cultural narratives, the cross evokes themes of divine favor and triumph over adversity, mirroring the archetype of the Cossack as a resilient fighter blessed by Providence. Epic songs (dumy) and legends frequently portray Cossacks invoking Christian protection during battles, aligning with the cross's representation of faith intertwined with martial valor—qualities Ataman Vitaly Kuznetsov explicitly linked to "faith and victory" in contemporary Cossack rituals.[19] Though not always depicted literally in folklore artifacts, its geometric form—expanding outward like a warrior's resolve—resonates with oral traditions of heroism against Ottoman, Polish, and Tatar foes, perpetuating a legacy of cultural defiance.[1] This enduring motif fosters continuity in Cossack-descended communities, where the cross adorns memorials and regalia to honor ancestral sacrifices, thereby sustaining ethnic pride and historical memory amid modern national revivals.[23] Such usage highlights causal ties between symbolic heritage and collective resilience, as evidenced in festivals and reenactments that dramatize Cossack exploits to instill values of bravery and sovereignty.[21]Military Applications

Use in Historical Cossack Formations

The Cossack cross featured prominently in the heraldry and military standards of early Cossack formations, particularly among the Zaporozhian Host. Dmytro Vyshnevetsky (c. 1517–1563), recognized as the founder of the first Zaporozhian Sich on Khortytsia Island in 1556, incorporated a white cross pattée into his coat of arms, which served as an emblem during campaigns against Crimean Tatar incursions and Ottoman forces.[24][2] This symbol underscored the Cossacks' role as frontier defenders aligned with Eastern Orthodox Christianity. In the 17th century, during the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1657), Cossack regimental banners often displayed crosses, including variants resembling the pattée form, as rallying symbols in battles against Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth armies. These standards, typically featuring religious iconography, reinforced unit cohesion and invoked divine protection amid irregular warfare tactics like ambushes and riverine raids.[25] Historical records indicate such crosses on flags captured from Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's forces, highlighting their integration into command structures for identification and morale. Later Cossack hosts, including Russian-line formations like the Orenburg Army established in 1748, adopted cross motifs on banners—often a central cross with rays on yellow fields bordered in red—for similar purposes in imperial service against steppe nomads and during expansions into Central Asia. These designs evolved from Zaporozhian precedents but adapted to tsarist hierarchies, appearing on guidons and regimental colors by the 19th century.[25] The cross's wedge-shaped arms facilitated visibility on horseback, aiding in the fluid maneuvers characteristic of Cossack cavalry.Integration into Modern Ukrainian Armed Forces

The Cossack cross forms a core element in the insignia and rank flags of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, particularly within the Ground Forces structure. Rank flags incorporate gold-embroidered Cossack crosses at the framework corners, surrounding the central emblem, as standardized in military protocol. This usage reflects efforts to revive historical Cossack symbolism amid post-2014 defense reforms, which restructured the armed forces to enhance combat readiness following the annexation of Crimea and conflict in Donbas.[4] Recent unit formations have prominently featured the symbol in their emblems. In July 2025, the 10th Army Corps adopted a design with three stylized Cossack crosses as central imagery, emphasizing operational identity.[26] Similarly, the 15th Army Corps incorporated a Cossack cross variant atop its Roman numeral designation in October 2025, blending tradition with modern command hierarchy.[27] The Ministry of Defence coat of arms also employs the Cossack cross, linking administrative oversight to Cossack heritage.[2] The symbol extends to military honors, with the Ukrainian Armed Forces awarding badges of the Order of the Commander of the Cossack Cross to distinguished defenders.[28] During the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, it appears in unit patches and vehicle markings resembling the isosceles form with expanding arms, serving for identification while evoking historical resilience.[2] These applications underscore the cross's role in fostering unit cohesion and national morale without supplanting primary symbols like the tryzub.Usage in Conflicts

Pre-20th Century Conflicts

The Cossack cross, characterized by its pattée form with wedge-shaped terminations, emerged in Eastern European heraldry during periods of Cossack militarization in the 16th to 18th centuries, reflecting Orthodox Christian defensive motifs amid recurrent steppe warfare. Zaporozhian Cossack hosts incorporated cross variants on seals, standards, and possibly weapon fittings during conflicts with Crimean Tatar raiders and Ottoman forces, as evidenced by 17th-century artifacts like L-guard swords featuring wedge-ended cross pattée guards potentially linked to Cossack usage. These symbols underscored the religious stakes in raids and campaigns, where Cossacks served as frontier irregulars, often numbering in the thousands, repelling incursions that devastated Ukrainian lands.[29][30] In the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1657), Zaporozhian forces under Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky mobilized up to 100,000 fighters, allying temporarily with Crimean Tatars to challenge Polish-Lithuanian dominance; banners bearing Christian crosses, including pattée forms, symbolized this Orthodox-led revolt, appearing in victories like Zhovti Vody (May 1648), where 3,000–4,000 Cossacks ambushed and annihilated an 8,000-strong Polish detachment. Similarly, during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), Cossack detachments contributed to Russian offensives, with heraldic crosses on regimental identifiers evoking continuity from earlier Sich traditions against shared Ottoman threats. However, primary accounts emphasize practical military motifs like eagles or archangels on flags, with the specific wedge-pattée design more consistently documented in post-conflict civic heraldry and monastic affiliations rather than battlefield standards.[31][1] The symbol's pre-20th century role thus aligned with Cossack identity as bulwarks of Eastern Christianity, appearing sporadically in artifacts from the Dnieper steppe amid chronic low-intensity conflicts—such as annual Tatar invasions peaking in the 16th century, which Cossacks countered through fortified sich outposts and seaborne raids on Ottoman ports. Its adoption likely drew from broader Byzantine and Kievan Rus' influences, adapted for mobile warfare where lightweight, recognizable emblems aided unit cohesion in decentralized hosts. Empirical evidence from archaeological and heraldic records remains fragmentary, prioritizing function over ornate symbolism in surviving 17th–18th century sources.[4][30]World War II Associations

During World War II, the Cossack cross appeared in the regimental insignia of certain Cossack cavalry units incorporated into the German Wehrmacht and later the Waffen-SS, reflecting the traditional symbolism of Don, Kuban, and Terek hosts who opposed Soviet rule. These units, recruited from anti-Bolshevik Cossack émigrés and POWs, totaled approximately 25,000–40,000 personnel by 1944, organized into formations such as the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division under General Helmuth von Pannwitz.[32][33] The cross, often rendered as a pattée variant, symbolized Cossack martial heritage amid their deployment in anti-partisan operations in Yugoslavia and southern Russia from 1943 onward.[34] A notable example is the "Kreuz des 5. Don-Kossaken-Reiter Regiments," a regimental award cross issued to members of the 5th Don Cossack Cavalry Regiment, one of four Don regiments within the division; this insignia featured a straight-armed cross pattée echoing historical Cossack designs, worn as a breast badge for combat merit.[35] Such symbols distinguished these volunteers from standard German forces, incorporating elements like papakha headgear and traditional shoulder boards alongside the cross to foster unit cohesion and morale.[36] In contrast, Soviet Cossack formations, such as the 4th and 5th Guards Cossack Cavalry Corps, emphasized Red Army iconography like the star and avoided pre-revolutionary Cossack symbols, including the cross, due to Bolshevik suppression of host identities.[32] The cross's wartime use by German-allied Cossacks later fueled post-war controversies, as surviving units faced forced repatriation to the USSR under the Yalta Agreement, resulting in mass executions; memorials to these Cossacks occasionally incorporated the symbol in exile communities, though primary associations remain tied to collaborationist military contexts rather than broader Ukrainian nationalist groups like the UPA, which favored the trident.[37][34] No evidence indicates systematic adoption by Axis or Allied forces beyond these ethnic Cossack contingents, underscoring the symbol's niche role in preserving host traditions amid ideological conflict.[38]Russo-Ukrainian War Deployments

During the 2022 Ukrainian counteroffensive in Kharkiv Oblast, Ukrainian forces applied white equilateral crosses with widening arms—resembling the Cossack cross—to vehicles for identification purposes, distinguishing them from Russian equipment amid rapid advances.[39] This marking paid homage to Cossack heraldic traditions, where similar crosses appeared on flags and standards as symbols of victory and resilience.[39][2] Similar inverted cross markings were employed in the 2023 counteroffensive, adapting the design for continued operational clarity while maintaining ties to historical Cossack iconography.[40] The Cossack cross also features in unit insignia, such as that of the 115th Mechanized Brigade, incorporating it alongside crossed sabers to evoke Ukrainian martial heritage.[41] In parallel, the symbol has been erected as monuments at cemeteries honoring war dead, including a "Cossack Cross" unveiled on October 14, 2022, at Odesa's Western Cemetery for soldiers killed defending Ukraine's independence.[42] Military awards bearing the Cossack cross, like the Order of the Commander of the Cossack Cross, have been conferred on defenders during the conflict to recognize valor.[28] Russian narratives have misrepresented these deployments as fascist emblems akin to Nazi markings, but historical records confirm the cross's pre-20th-century Cossack origins, predating and unrelated to German World War II symbols.[43][2] Empirical evidence from Ukrainian military heraldry and Cossack artifacts substantiates its indigenous defensive and commemorative role.[44]Controversies and Interpretations

Allegations of Extremist Symbolism

Allegations portraying the Cossack cross as an extremist symbol have surfaced primarily in Russian state media and affiliated online discourse, framing its use in Ukrainian military contexts as evidence of neo-Nazi ideology. These claims often cite visual parallels between simplified Cossack cross variants—such as white tactical markings on Ukrainian vehicles during the 2022 counteroffensive—and the Balkenkreuz, a black cross employed by Nazi Germany's Wehrmacht for vehicle identification. Russian narratives assert that such markings glorify fascist heritage, integrating them into broader accusations of Ukrainian "denazification" needs.[2][44] Proponents of these allegations, including commentators on platforms like Telegram and X, link the symbol to far-right Ukrainian nationalist groups, suggesting its prominence in emblems of units like Azov or in Cossack revivalist movements signals extremist revivalism akin to historical collaborations with Axis forces during World War II. For instance, social media posts have highlighted Cossack cross-bearing flags at nationalist rallies in western Ukraine as indicative of ultra-nationalist sentiment. Russian propaganda extends this by equating Cossack symbolism with "Banderite" fascism, referencing Stepan Bandera's Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, to dehumanize Ukrainian identity.[45] These interpretations rely on Russian state-driven narratives that systematically label Ukrainian national symbols, including those tied to Cossack heritage, as fascist to justify the 2022 invasion under the pretext of combating extremism, despite the cross's longstanding roots in Eastern Orthodox Christianity predating Nazi iconography by centuries.Russian Propaganda Claims vs. Empirical Evidence

Russian state media and officials have asserted that white crosses painted on Ukrainian military vehicles, particularly during the 2022 Kharkiv counteroffensive, constitute Nazi symbols akin to the Balkenkreuz used by Wehrmacht forces in World War II.[2] These claims portray the markings as evidence of fascist ideology within the Ukrainian armed forces, supporting Russia's stated goal of "denazification" as justification for its invasion launched on February 24, 2022.[43] [46] Similar accusations extend to broader Cossack cross usage, framing it as extremist or neo-Nazi iconography to discredit Ukrainian national symbols.[47] Empirical examination reveals the Cossack cross—an equilateral or pattée wedge form—as a heraldic element rooted in the traditions of Zaporozhian Cossacks, autonomous East Slavic warrior communities active from the mid-15th to late 18th centuries along the Dnieper River lowlands.[22] This predates the Nazi regime by over two centuries, with no documented adoption or modification by National Socialist ideology; Nazi symbology emphasized the swastika, runes, and angular Balkenkreuz variants distinct from Cossack patterns.[39] Historical records confirm its use in Cossack flags, seals, and regalia as a Christian-derived emblem of martial valor, not racial supremacy.[48] In contemporary Ukraine, the symbol appears on regional flags such as those of Poltava and Rivne oblasts, military awards like the Order of Bohdan Khmelnytsky established in 1995, and civilian memorials without ties to far-right groups.[39] Independent fact-checks, including those monitoring Russian disinformation since 2014, consistently refute Nazi associations, attributing vehicle markings to tactical identification echoing Cossack heritage rather than ideological endorsement.[47] [43] Russian claims, disseminated via state-controlled outlets like RT and Sputnik, align with patterns of historical revisionism documented by European intelligence assessments, prioritizing narrative over verifiable chronology.[46]Ukrainian Nationalist Perspectives

Ukrainian nationalists interpret the Cossack cross as a venerable emblem rooted in the Zaporozhian Cossack tradition of the 16th to 18th centuries, symbolizing martial independence, communal self-governance, and defiance against Ottoman, Polish-Lithuanian, and Muscovite incursions.[49] They position Cossacks as proto-ethnic forebears of the Ukrainian nation, whose semi-autonomous hosts exemplified resistance to external domination, thereby framing the cross as an assertion of ancestral sovereignty rather than foreign or ideological import.[49] This perspective elevates the symbol's heraldic use in Cossack flags and regalia—such as equilateral crosses denoting host banners—as evidence of organic cultural continuity, predating 20th-century ideological conflicts.[39] In commemorative practices, nationalists erect Cossack crosses at sites honoring victims of Russian imperial and Soviet repression, viewing them as tributes to Ukrainians persecuted for national aspirations. A prominent example is the 2005 limestone Cossack cross at Sandarmokh, inscribed "To the Murdered Sons of Ukraine," commemorating over 7,000 executed prisoners from the 1937–1938 Great Terror, many ethnic Ukrainians targeted for perceived disloyalty.[50] This usage underscores a narrative of the cross as a marker of unyielding national martyrdom, with traditions extending to graves of independence fighters, reinforcing its role in fostering collective memory against historical erasure.[51] Similarly, a 2022 "Cossack Cross" monument at Odesa's Western Cemetery honors fallen defenders of Ukraine's territorial integrity since 2014, aligning the symbol with contemporary sacrifices.[42] Amid allegations of extremist connotations, Ukrainian nationalists maintain that the Cossack cross embodies pre-modern Cossack valor and anti-colonial struggle, distinct from unrelated 20th-century appropriations. They cite its appearance in regional heraldry, such as Poltava Oblast's flag featuring a yellow Cossack cross on blue since 2000, as proof of mainstream patriotic legitimacy rather than fringe radicalism.[52] In rallies and insignia, it serves as a badge of sovereignty pride, with proponents arguing that equating it to foreign symbology ignores empirical Cossack precedents, such as vehicle markings evoking host tactics during the 2022 Kharkiv counteroffensive.[39] This defense prioritizes historical attestation over narrative-driven critiques, positing the cross as a bulwark of Ukrainian self-determination.[43]Memorial and Civic Uses

Monuments and Grave Markers

The Cossack cross features prominently in monuments dedicated to historical Ukrainian Cossacks and victims of repression. In Poltava, the Monument to Fallen Ukrainian Cossacks, erected to commemorate those who perished in the Battle of Poltava on July 8, 1709, centers on an enormous Cossack cross atop a pedestal inscribed "To Ukrainian Fallen Cossacks."[53] Similarly, at the Sandarmokh site in Karelia, a limestone Cossack cross installed in 2005 honors over 1,000 Ukrainians executed by the NKVD during the Great Purge of 1937–1938, bearing the inscription "To the Murdered Sons of Ukraine."[54] In contemporary Ukraine, the symbol appears in memorials for soldiers killed in defense of the nation. On October 14, 2022, a "Cossack Cross" monument was unveiled at Odesa's Western Cemetery to commemorate defenders who died for Ukraine's independence and territorial integrity.[42] Another such memorial, symbolizing the Cossack cross, was dedicated at Kyiv's Berkovets Cemetery to thousands of fallen warriors.[55] As grave markers, Cossack crosses denote burials in historical and modern military contexts. Ancient Cossack cemeteries, such as Usatove near Odesa and Kuialnyk (Sotnykiv cemetery), preserve stone Cossack crosses dating back to the 18th century, including one from 1791 at Kuialnyk marking early Zaporozhian graves.[56] In the National Military Memorial Cemetery, established for Ukraine's war dead, temporary wooden Cossack cross markers are used pending permanent stone versions approved by government resolution on July 13, 2024, which permits Cossack cross or rectangular tablet shapes for tombstones.[57][58] This design evokes traditional Cossack burial practices while honoring contemporary sacrifices.[59]Awards and Insignia

The Cossack Cross (Ukrainian: Козацький хрест) serves as a military decoration awarded by the Commander of the Joint Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, established to recognize distinguished service, particularly in combat operations against aggression. It is conferred in three degrees, with the design incorporating the characteristic pattée cross with wedge-shaped arms, often rendered in metal with enamel accents and crossed swords symbolizing martial valor. Recipients include personnel demonstrating exceptional leadership or contributions in defensive actions, as evidenced by post-2014 conflict bestowals amid the Russo-Ukrainian War.[60] Beyond official military usage, the Cossack cross appears in insignia and awards of Cossack heritage organizations, such as the Ukrainian Registered Cossacks, where it denotes membership ranks, merit for preserving traditions, and service in paramilitary or cultural capacities. These include variants like the "Cross of the Ukrainian Cossacks with Swords," typically gold- or silver-plated brass pieces measuring approximately 40-50 mm, awarded for loyalty to Cossack ideals and defense efforts. Such awards, produced since Ukraine's independence, emphasize historical continuity with Zaporozhian traditions rather than modern standardization.[61][62] In broader Ukrainian defense contexts, the cross features on departmental badges, such as those from the Ministry of Defence's Badge of Honour, honoring logistical or auxiliary support to forces, though not as the central element. Empirical records from collector databases and official listings confirm over a dozen such iterations since 1991, prioritizing verifiable merit over ceremonial inflation, with higher degrees reserved for direct combat validation.[63]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coa_Illustration_Cross_Pattee_wedge.svg

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2023_Ukrainian_Counteroffensive_inverted_cross_vehicle_marking.svg

![Historical Cossack flag from 1651 exhibited in the Armémuseum in Stockholm[15]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f6/%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%B7%D0%B0%D1%86%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%80%2C_1651_%D1%80._21.jpg/120px-%D0%9A%D0%BE%D0%B7%D0%B0%D1%86%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%BE%D1%80%2C_1651_%D1%80._21.jpg)