Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

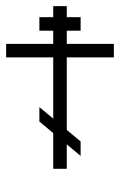

Russian Orthodox cross

View on Wikipedia Orthodox cross

|

|

|

|

The Russian Orthodox Cross (or just the Orthodox Cross by some Russian Orthodox traditions)[1] is a variation of the Christian cross since the 16th century in Russia, although it bears some similarity to a cross with a bottom crossbeam slanted the other way (upwards) found since the 6th century in the Byzantine Empire. The Russian Orthodox cross has three horizontal crossbeams, with the lowest one slanted downwards. Today it is a symbol of the Russian Orthodox Church[2][3][4] and a distinctive feature of the cultural landscape of Russia.[5] Other names for the symbol include the Russian cross, and Slavonic or Suppedaneum cross.

The earliest cross with a slanted footstool (pointing upwards, unlike the Russian cross) was introduced in the 6th century before the break between Catholic and Orthodox churches, and was used in Byzantine frescoes, arts, and crafts. In 1551 during the canonical isolation of the Russian Orthodox Church, Ivan the Terrible, Grand Prince of Moscow, first used this cross, with the footstool tilted the other way, on the domes of churches.[6][7] From this time, it started to be depicted on the Russian state coat of arms and military banners. In the second half of the 19th century, this cross was promoted by the Russian Empire in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a symbol of its Russification policy.[8]

One variant known as the Russian cross has only two horizontal crossbeams with the lower one slanted;[9] another is the cross over crescent variant.[10][11][6] Some Russian sources distinguish the Russian Orthodox cross from the Orthodox cross.[12] In Unicode the symbol (☦) is denoted as Orthodox cross.[13] The same USVA headstone emblem is called Russian Orthodox cross.[14]

Name

[edit]According to many sources[2][15][16] the name of the three beam slanted cross is Russian (Orthodox) cross (Russian: русский православный крест[3]).

Sometimes it is also called the Byzantine cross.[17] Alternatively, "Byzantine cross" is also the name for a Latin cross with outwardly spreading ends, as it was the most common cruciform in the Byzantine Empire. Other crosses (patriarchal cross, Russian Orthodox cross, etc.) are sometimes denominated as Byzantine crosses, as they also were used in Byzantine culture.

Sometimes it is also called just Orthodox cross.[18][19] At the same time the various Orthodox churches use different crosses, and any of them may be called an "Orthodox cross".[12] Moreover, there are no crosses universally acknowledged as "Orthodox" or "Catholic": each type is a feature of local tradition.[5] The cross has also been referred to as the "Eastern Cross", and "has a special place in Ukrainian religious life" and has been used by Ukrainian Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches.[20] For example, this particular cross is dates back to Kievan Rus', and is used by Ukrainian Catholics and Orthodox Christians.[21][22]

Meaning

[edit]

The topmost of the three crossbeams represents Pilate's inscription which in the older Greek tradition is "The King of Glory", based on John's Gospel; but in later images it represents INRI. The middle crossbeam is the main bar to which the victim's hands are fixed, while the bottom crossbeam represents the footrest which prolongs the torture. In many depictions, the side to Christ's right is higher, slanting upward toward the penitent thief St. Dismas, who was crucified on Jesus' right, but downward toward impenitent thief Gestas, who mocked Christ on the cross (Luke 23:39–43). Their names are preserved not in the Gospels, but in the apocryphal tradition.[4][23] It is also a common perception that the foot-rest points up, toward Heaven, on Christ's right hand-side, and downward, to Hell, on Christ's left. The cross is often depicted in icons "of the crucifixion in historic Byzantine style".[24]

One variation of the Russian Cross is the 'Cross over Crescent', which is sometimes accompanied by "Gabriel perched on the top of the Cross blowing his trumpet."[10][6] Didier Chaudet, in the academic journal China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, writes that an "emblem of the Orthodox Church is a cross on top on a crescent. It is said that this symbol was devised by Ivan the Terrible, after the conquest of the city of Kazan, as a symbol of the victory of Christianity over Islam through his soldiers".[25][11][6][26]

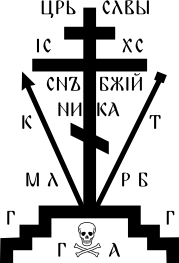

Another variation is the monastic Calvary Cross, in which the cross is situated atop the hill of Calvary, its slopes symbolized by steps. To the viewer's left is the Holy Lance, with which Jesus was wounded in his side, and to the right, the pole topped by a hyssop sponge with which he was given vinegar. Under Calvary are Adam's skull and bones;[27] the right-arm bone is usually above the left one, and believers fold their arms across their chests in this way during Orthodox communion. Around the cross are abbreviations in Church Slavonic: ЦР҃Ь СЛ҃ВЫ — «Царь Славы», Lord of Glory; ІС҃ ХС҃ - Иисус Христос, Jesus Christ; СН҃Ъ БЖ҃ІЙ — «Сын Божий» Son of God; НИКА - Victor; К - копьё, spear; Т - трость, pole (with a sponge); М Л Р Б — «место лобное рай бысть» "place of execution is paradise", Г Г — «гора Голгофа» "mount Golgotha" (Calvary), Г А — «глава Адамова» "Adam's head". This type of cross is usually embroidered on a schema-monk's robe.

Current usage

[edit]The Russian (Orthodox) cross is widely used by the Russian Orthodox Church, and has been widely adopted in the Polish Orthodox and the Czech and Slovak Orthodox Churches, which received their autonomous status from the Patriarch of Moscow in 1948 and 1951 respectively. It is also sometimes used by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (e.g. in the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese). "Though commonly associated with the Russian Orthodox Church, this [cross] is found also in the Greek and Serbian Orthodox churches" and is also used by Eastern Rite Catholic Churches.[28]

This cross is also found in Byzantine frescoes in churches now belonging to the Greek and Serbian Orthodox churches.[29] The Cross is also used by African Independent Pentecostal Church of Africa (AIPCA) in Kenya. [citation needed]

History

[edit]The slanted cross with three horizontal crossbeams existed already in the 6th century, long before the Great Schism. However, it was used only in church paintings, arts and crafts, and never on church domes.[citation needed] There are old frescoes depicting this type of cross in the regions of modern Greece and Serbia. One Byzantine icon featuring the three-bar cross, with the slanted crossbeam for the feet of Christ, is an 11th century mosaic of the resurrection.[30] The three-bar cross "existed very early in Byzantium, but was adopted by the Russian Orthodox Church and especially popularized in Slavic countries."[31]

At the end of the 15th century this cross started to be widely used in Russian Tsardom when its rulers declared themselves the "Third Rome", successors of Byzantium and defenders of Orthodoxy.[32] In 1551 at the council of the canonically isolated Russian Orthodox Church, the Grand Prince of Moscow Ivan the Terrible decided to standardize the cross on Russian church domes to distinguish Russian Tsardom from the "Lithuanian, Polack cross".[33] This was the first time the Russian Orthodox Cross was used on church domes. During 1577–1625, the Russian Orthodox cross was depicted between the heads of a double-headed eagle in the coat of arms of Russia. It was drawn on military banners until the end of the 17th century.[34]

In 1654, the Moscow council, erasing the vestiges of the canonical isolation of 1448–1589, coordinated Russian Orthodox liturgy with that of other Orthodox churches.[35][36] At this council, Patriarch Nikon ordered the use of the Greek cross instead of Russian Orthodox cross. These reforms provoked the Raskol schism.[37] Replacement of the Russian Orthodox cross by Greek cross was caused by Russian disrespect for the second one.[38] Soon, however, the Russian Orthodox Church began to use the Russian Orthodox cross again. According to the Metropolitan of Ryazan and Murom Stefan, the Russian Orthodox cross was worn by Czar Peter I[32] (1672–1725), who transformed the Moscow Patriarchate into the Most Holy Synod.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Russian Orthodox cross was promoted by the Russian Empire and USSR in Belarus, Poland and Ukraine as a part of Russification policies.[23][39][40] At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, the Russian Orthodox Church replaced many traditional Greek Orthodox crosses in Belarus with Russian Orthodox crosses.[5] This suggests that it was understood as a nationalist Russian symbol rather than a religious Orthodox one.[citation needed]

The Russian Orthodox cross is depicted on emblems of several Russian ultra-nationalist organizations such as Brotherhood of Russian Truth and Russian National Unity.

Gallery

[edit]-

A folio from the Vani Gospels manuscript, copied at the behest of Queen Tamar.

-

A 17th-century miniature of the Battle of Kulikovo (1380). A warrior bears a red banner with a cross.

-

Coat of arms of Russia from the seal of Ivan IV (the Terrible), 1577

-

Coat of arms of Russia from the seal of Fyodor I, 1589

-

Russian military flag, 1696–1699

-

Russian military flag, 1706

-

A copper cross typical for Old believers

-

A cross of a Russian Orthodox priest

-

A modern memorial to Ss. Cyril and Methodius in Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia

-

Coat of arms of Moscow Oblast, 2005

-

Coat of arms of Perm Krai, 2007

-

Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois Russian Cemetery, the resting place of many eminent Russian émigrés

-

Białystok (Poland): Crosses on the domes of the Church of the Holy Spirit

-

Johnstown, Pennsylvania: Christ the Saviour Cathedral of the American Carpatho-Russian Orthodox Diocese (under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople)

-

Svidník (Slovakia): Cross in front of a church

-

Flag of the Brotherhood of Russian Truth

-

Flag of RNU

-

USVA Headstone Emblem 5 "Russian Orthodox cross"

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Russian Orthodox Cross - Questions & Answers". www.oca.org. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ a b Liungman, Carl G. (2004). Symbols - Encyclopedia of Western Signs and Ideograms. Ionfox AB. p. 140. ISBN 978-91-972705-0-2.

- ^ a b Святейший Патриарх Московский и всея Руси Кирилл. Воздвижение Честного и Животворящего Креста Господня // Тихвинский листок №41, 27 Сентября 2017.

- ^ a b Фещин А. Довірся Хресту // Християнский голос. — 2002. — № 18 (2854). С. 232.

- ^ a b c Бурштын Я. Ірына Дубянецкая: Дзякуючы намаганням РПЦ пачынае мяняцца культурны ландшафт Беларусі (Фота і відэа) // Служба інфармацыі «ЕўраБеларусі», 16 ліпеня 2016 г.

- ^ a b c d Hunter, Shireen (2016). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and Security: The Politics of Identity and Security. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-29011-9.

Thus the conquest of Kazan by Ivan the Terrible was also viewed as the triumph of Christianity over Islam, symbolized by the cross placed above the crescent atop Russian churches.

- ^ Русский крест: символика православного надглавного креста. — Москва, 2006. С. 149.

- ^ Мілаш Я. Традыцыі ўшанавання крыжа беларусамі ў канцы XIX ст. // Наша Вера. № 3 (65), 2013.

- ^ Рэлігія і царква на Беларусі: Энцыкл. даведнік — Мн.: БелЭн, 2001. С. 168.

- ^ a b Stevens, Thomas (1891). Through Russia on a Mustang. Cassell. p. 248. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

It seemed rather rough on Tartars, too, as showing scant consideration for the religious susceptibilities of a subject people, to find some of the domes of the Orthodox churches ornamented with devices proclaiming the triumph of the Cross over the Crescent. A favorite device is a Cross towering above a Crescent, with Gabriel perched on the top of the Cross blowing his trumpet.

- ^ a b "Russian Orthodox Church". Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. 17: 4. 1993. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

Finally, the Russians, under Ivan the Terrible, defeated the Tatars in 1552 and firmly established Russian rule. In celebration of this conquest, the czar built two churches in the Moscow Kremlin and on the spires of the Church installed the Orthodox Cross over an upside down crescent, the symbol of Islam.

- ^ a b "Православные кресты: как разобраться в значениях" [Orthodox crosses: how to understand the meanings] (in Russian). 30 September 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Unicode Character 'ORTHODOX CROSS' (U+2626).

- ^ Available Emblems of Belief for Placement on Government Headstones and Markers, Supreme Court of the United States

- ^ Thomas, Robert Murray (2007). Manitou and God: North-American Indian religions and Christian culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-313-34779-5.

- ^ Milo D. L. The Ankh: Key of Life. — Weiser Books, 2007. P. 13.

- ^ Becker U. The Continuum Encyclopedia of Symbols. — New York London, 2000. P. 71.

- ^ Chwalkowski F. Symbols in Arts, Religion and Culture: The Soul of Nature. — Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016. P. 112

- ^ "Why are we seeing orthodox crosses on Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches and literature? Is the orthodox cross allowed to be used?". Edmonton Eparchy. 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Kostecki, A. M. (January 1989). "View of Crosses of East Slavic Christianity among Ukrainians in Western Canada | Material Culture Review". journals.lib.unb.ca. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ "Why are we seeing orthodox crosses on Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches and literature? Is the orthodox cross allowed to be used?". Edmonton Eparchy. 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Communications, Eparchy (2020-09-15). "Why are we seeing orthodox crosses on Ukrainian Greek Catholic churches and literature? Is the orthodox cross allowed to be used?". Edmonton Eparchy. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ a b Яременко В. Золоте Слово: Хрестоматія літератури України-Русі епохи Середньовіччя IX—XV століть. Книга перша. — Київ: Аконіт, 2002. С. 485.

- ^ "Why Orthodox Christians see triumph in the cross". The Christian Century. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Chaudet, Didier (2009). "When the Bear Confronts the Crescent: Russia and the Jihadist Issue". China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly. 7 (2). Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program: 37–58. ISSN 1653-4212.

It would be convenient to characterize the relationship between Russia and Islam by its history of conquest and tension. After all, the emblem of the Orthodox Church is a cross on top on a crescent. It is said that this symbol was devised by Ivan the Terrible, after the conquest of the city of Kazan, as a symbol of the victory of Christianity over Islam through his soldiers.

- ^ "Church Building and Its Services". Orthodox World. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

Sometimes the bottoms of the Crosses found on Russian churches will be adorned with a crescent. In 1486, Tsar Ivan IV (the Terrible) conquered the city of Kazan which had been under the rule of Moslem Tatars, and in remembrance of this, he decreed that from henceforth the Islamic crescent be placed at the bottom of the Crosses to signify the victory of the Cross (Christianity) over the Crescent (Islam).

- ^ McGuckin, John Anthony (2011). "Cross". In John Anthony McGuckin (ed.). The encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. Vol. 1. John Wiley and Sons. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4051-8539-4.

- ^ "Cross, Orthodox | City of Grove Oklahoma". www.cityofgroveok.gov. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Gerstel, Sharon (2006). "An Alternate View of the Late Byzantine Sanctuary Screen," in Thresholds of the Sacred: Art Historical, Archaeological, Liturgical and Theological Views on Religious Screens, East and West, ed. S. Gerstel. pp. 146–47.

- ^ "Imagery of Orthodox Easter | Vasileios Marinis and Martin Jean | Institute of Sacred Music". ism.yale.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ "- The Cross". www.stgeorgecanton.org. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ a b Гнідець Р. Св. Хрест, його форма та різновиди в Україні // Греко-Католицька Традиція №9 (193), вересень 2013 р.

- ^ Белы А. Крыж Еўфрасінні Полацкай // Наша Слова. № 29 (817) 1 жнiўня 2007 г.

- ^ Shpakovsky, Viacheslav; Nicolle, David; McBride, Angus (2006). "Infantry and cavalry banners". Armies of Ivan the Terrible: Russian Troops 1505-1700. Osprey Publishing. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84176-925-7.

- ^ Мицик Ю. Московський Патріархат // Енциклопедія історії України : у 10 т. / редкол.: В. А. Смолій (голова) та ін. ; Інститут історії України НАН України. — К.: Наук. думка, 2010. — Т. 7 : Мл — О. С. 87.

- ^ Нуруллаев А. А. Нуруллаев А. Ал. Религия и политика. — М., 2006. С. 299.

- ^ Изотова О., Касперович Г., Гурко А., Бондарчик А. Кто живет в Беларуси. — Минск: «Беларуская навука», 2012. С. 740

- ^ Русский крест: символика православного надглавного креста. — Москва, 2006. С. 147.

- ^ Щербаківський В. Чи трираменний хрест із скісним підніжком – національний хрест України? // Визвольний шлях. — 1952, листопад. — Ч. 11 (62). С. 33—34.

- ^ Білокінь С. Українська форма хреста // Укр. слово. — 1994. — № 17 (2713).

External links

[edit]- "Explanation of the Three-Bar Cross". Church of the Nativity: Russian Orthodox Old Rite. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Kuznetsov, V. P. [Кузнецов В. П.] (1997). History of the development of the cross's forms. Short course of Orthodox staurography [История развития формы креста. Краткий курс православной ставрографии] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)