Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Crips

View on Wikipedia

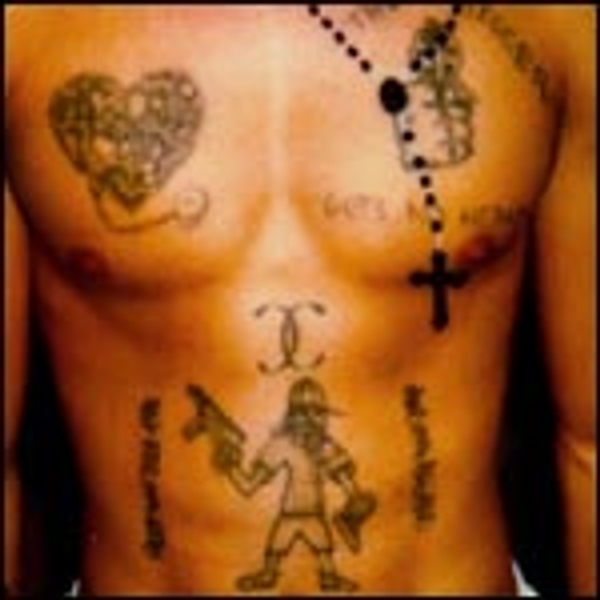

Tattooed Crip | |

| Founded | 1969 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Raymond Washington Stanley Williams |

| Founding location | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Territory | 41 U.S. states,[1] Canada[2] and Belize[3] |

| Ethnicity | Predominantly African American[1] |

| Membership (est.) | 30,000–35,000[4] |

| Activities | Drug trafficking, murder, assault, auto theft, burglary, extortion, fraud, robbery[1] |

| Allies | |

| Rivals | |

| Notable members | |

The Crips are a primarily African-American alliance of street gangs that are based in the coastal regions of Southern California. Founded in Los Angeles, California, in 1969, mainly by Raymond Washington and Stanley Williams, the Crips began as an alliance between two autonomous gangs, and developed into a loosely connected network of individual "sets", often engaged in open warfare with one another. Its members have traditionally worn blue clothing since around 1973.

The Crips are one of the largest and most violent associations of street gangs in the United States.[23] With an estimated 30,000 to 35,000 members in 2008,[4] the gangs' members have been involved in murders, robberies, and drug dealing, among other crimes. They have a long and bitter rivalry with the Bloods.

Some self-identified Crips have been convicted of federal racketeering.[24][25]

Etymology

[edit]Some sources suggest that the original name for the alliance, "Cribs", was narrowed down from a list of many options and chosen unanimously from three final choices, over the Black Overlords and the Assassins. Cribs was chosen to reflect the young age of the majority of the gang members. The name evolved into "Crips" when gang members began carrying around canes to display their "pimp" status. People in the neighborhood then began calling them cripples, or "Crips" for short.[26] In February 1972 the Los Angeles Times used the term.[23]

Another source suggests "Crips" may have evolved from "Cripplers", a 1970s street gang in Watts, of which Washington was a member.[27] The name had no political, organizational, cryptic, or acronymic meaning, though some have suggested it stands for "Common Revolution In Progress", a backronym. According to the film Bastards of the Party, directed by a former member of the Bloods, the name represented "Community Revolutionary Interparty Service" or "Community Reform Interparty Service".

History

[edit]Gang activity in South Central Los Angeles has its roots in a variety of factors dating to the 1950s, including: post-World War II economic decline leading to joblessness and poverty; racial segregation of young African American men, who were excluded from organizations such as the Boy Scouts, leading to the formation of black "street clubs"; and the waning of black nationalist organizations such as the Black Panther Party and the Black Power Movement.[28][29][30][31]

Stanley "Tookie" Williams met Raymond Lee Washington in 1969, and the two decided to unite their local gang members from the west and east sides of South Central Los Angeles in order to battle neighboring street gangs. Most of the members were 17 years old.[32] Williams however appears to discount the sometimes-cited founding date of 1969 in his memoir, Blue Rage, Black Redemption.[32]

In his memoir, Williams also refuted claims that the group was a spin-off of the Black Panther Party or formed for a community agenda, writing that it "depicted a fighting alliance against street gangs—nothing more, nothing less."[32] Washington, who attended Fremont High School, was the leader of the East Side Crips, and Williams, who attended Washington High School, led the West Side Crips.

Williams recalled that a blue bandana was first worn by Crips founding member Curtis "Buddha" Morrow, as a part of his color-coordinated clothing of blue Levis, a blue shirt, and dark blue suspenders. A blue bandana was worn in tribute to Morrow after he was shot and killed on February 23, 1973. The color then became associated with Crips.[32]

By 1978, there were 45 Crip gangs, called sets, in Los Angeles. They were heavily involved in the production of PCP,[33] marijuana and amphetamines.[34][35] On March 11, 1979, Williams, a member of the Westside Crips, was arrested for four murders and on August 9, 1979, Washington was gunned down. Washington had been against Crip infighting and after his death several Crip sets started fighting against each other. The Crips' leadership was dismantled, prompting a deadly gang war between the Rollin' 60 Neighborhood Crips and Eight Tray Gangster Crips that led nearby Crip sets to choose sides and align themselves with either the Neighborhood Crips or the Gangster Crips, waging large-scale war in South Central and other cities. The East Coast Crips (from East Los Angeles) and the Hoover Crips directly severed their alliance after Washington's death. By 1980, the Crips were in turmoil, warring with the Bloods and against each other.

Nicaraguan Revolution, Contras, and increased drug trafficking

[edit]After the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979, many of the former government people of Anastasio Somoza Debayle fled to the U.S. and were supported by the CIA to counter the communists. Enrique Bermúdez was allegedly picked by the CIA to head the contras, who met with Oscar Danilo Blandón and Norwin Meneses to discuss fundraising. They decided to use drug trafficking to raise funds, and targeted black communities in South Los Angeles.[36]

The gang's growth and influence increased significantly in the early 1980s when crack cocaine boomed and Crip sets began distributing the drug. Large profits induced many Crips to establish new markets in other cities and states. As a result, Crips membership grew steadily and the street gang was one of the nation's largest by the late 1980s.[37][38] In 1999, there were at least 600 Crip sets with more than 30,000 members transporting drugs in the United States.[23]

Membership

[edit]As of 2015, the Crips gang consists of between approximately 30,000 and 35,000 members and 800 sets, active in 221 cities and 41 U.S. states.[1] The states with the highest estimated number of Crip sets are California, Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Members typically consist of young African American men, but can be white, Hispanic, Asian, and Pacific Islander.[23] The gang also began to establish a presence in Canada in the early 1990s;[39] Crip sets are active in the Canadian cities of Montreal and Toronto.[40][41]

In 1992 the LAPD estimated 15,742 Crips in 108 sets; other source estimates were 30,000 to 35,000 in 600 sets in California.[42]

Crips have served in the United States armed forces and on military bases in the United States and abroad.[43]

Practices

[edit]

Language

[edit]Some practices of Crip gang life include graffiti and substitutions and deletions of particular letters of the alphabet. The letter "b" in the word "blood" is "disrespected" among certain Crip sets and written with a cross inside it because of its association with the enemy. The letters "CK", which are interpreted to stand for "Crip killer", are avoided and replaced by "cc". For example, the words "kick back" are written "kicc bacc", and block is written as "blocc". Many other words and letters are also altered due to symbolic associations.[44] Crips traditionally refer to each other as "Cuz" or "Cuzz", which itself is sometimes used as a moniker for a Crip. "Crab" is the most disrespectful epithet to call a Crip, and can warrant fatal retaliation.[45] Crips in prison modules in the 1970s and 1980s sometimes spoke Swahili to maintain privacy from guards and rival gangs.[46]

Criminal rackets and street activities

[edit]As with most criminal street gangs, Crips have benefited monetarily from illicit activities such as illegal gambling, drug-dealing, pimping,[47] larceny, and robbery.[1] Crips also profit from extorting local drug dealers who are not members of the gang.[citation needed] Along with profitable rackets such as these, they also participate in vandalism and property crime, often for gang-pride reasons[citation needed] or simply enjoyment.[citation needed] This can include public graffiti (tagging) and "joyriding" in stolen vehicles.[citation needed]

The gang's current primary source of income is street-level drug distribution,[citation needed] however many Crip members also make notable amounts of funds from the black market sale of illicit firearms. The gang's size and power was greatly augmented by the profits from the street sale of crack cocaine throughout the 1980s.[citation needed] The gang's initial phase of growth and popularity was due to the explosion of crack cocaine in the United States during the 1980s.[citation needed]

Crip-on-Crip rivalries

[edit]The Crips became popular throughout southern Los Angeles as more youth gangs joined; at one point they outnumbered non-Crip gangs by 3 to 1, sparking disputes with non-Crip gangs, including the L.A. Brims, Athens Park Boys, the Bishops, The Drill Company, and the Denver Lanes. By 1971 the gang's notoriety had spread across Los Angeles.

By 1971, a gang on Piru Street in Compton, California, known as the Piru Street Boys, formed and associated itself with the Crips as a set. After two years of peace, a feud began between the Pirus and the other Crip sets. It later turned violent as gang warfare ensued between former allies. This battle continued and by 1973, the Pirus wanted to end the violence and called a meeting with other gangs targeted by the Crips. After a long discussion, the Pirus broke all connections to the Crips and started an organization that would later be called the Bloods,[48] a street gang infamous for its rivalry with the Crips.

Since then, other conflicts and feuds were started between many of the remaining Crip sets. As well as feuding with Bloods, they also fight each other — for example, the Rolling 60s Neighborhood Crips and 83 Gangster Crips have been rivals since 1979. In Watts, the Grape Street Crips and the PJ Watts Crips have feuded so much that the PJ Watts Crips even teamed up with a local Blood set, the Bounty Hunter Bloods, to fight the Grape Street Crips.[49] In the mid-1990s, the Hoover Crips rivalries and wars with other Crip sets caused them to become independent and drop the Crip name, calling themselves the Hoover Criminals.

Alliances and rivalries

[edit]Rivalry with the Bloods

[edit]The Bloods are the Crips' main rival. The Bloods initially formed to provide Piru Street Gang members protection from the Crips. The rivalry started in the 1960s when Washington and other Crip members attacked Sylvester Scott and Benson Owens, two students at Centennial High School. After the incident, Scott formed the Pirus, while Owens established the West Piru gang.[50] In late 1972, several gangs that felt victimized by the Crips due to their escalating attacks joined the Pirus to create a new federation of non-Crip gangs that later became known as Bloods. Between 1972 and 1979, the rivalry between the Crips and Bloods grew, accounting for a majority of the gang-related murders in southern Los Angeles. Members of the Bloods and Crips occasionally fight each other and, as of 2010, are responsible for a significant portion of gang-related murders in Los Angeles.[51] This rivalry is also believed to be behind the 2022 Sacramento shooting, where six people were killed.[52] On June 15, 2025, a teenager allegedly opened fire during a festival in West Valley City, Utah, killing three people including an eight-month-old infant and wounding two others; one of the two wounded was pregnant and the fetus was not delivered as a result, thus leading a fourth murder charge. The shooter was suspected to be a Titanic Crip Gang member and was feuding with alleged Bloods members as gang epithets were being espoused during a friction; at least one of the victims had ties or friendships with the Bloods gang.[53]

Alliance with the Folk Nation

[edit]In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as many Crip gang members were being sent to various prisons across the country, an alliance was formed between the Crips and the Folk Nation in Midwest and Southern U.S. prisons. This alliance was established to protect gang members incarcerated in state and federal prison. It is strongest within the prisons, and less effective outside. The alliance between the Crips and Folks is known as "8-ball". A broken 8-ball indicates a disagreement or "beef" between Folks and Crips.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Criminal Street Gangs" Archived February 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Justice (May 12, 2015)

- ^ Matt Kwong (January 19, 2015), "Canada's gang hotspots — are you in one?" Archived April 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- ^ "How the US Exported a Bloods and Crips Gang War to Belize". July 15, 2021. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ a b "Appendix B. National-Level Street, Prison, and Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Profiles – Attorney General's Report to Congress on the Growth of Violent Street Gangs in Suburban Areas (UNCLASSIFIED)". www.justice.gov. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ "In our world, killing is easy': Latin Kings part of a web of organized crime alliances, say former gangsters and law enforcement officials". MassLive. December 28, 2019. Archived from the original on December 18, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- ^ "Major Prison Gangs(continued)". Gangs and Security Threat Group Awareness. Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, Jarrod. "The rise and development of gangs in New Zealand" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2023.

- ^ "Los Angeles-based Gangs — Bloods and Crips". Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on October 27, 2002. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Echo Day (December 12, 2019), "Here's what we know about the Gangster Disciple governor who was sentenced to 10 years in prison" Archived February 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, The Leader

- ^ "Juggalos: Emerging Gang Trends and Criminal Activity Intelligence Report" (PDF). Info.publicintelligence.net. February 15, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2017.

- ^ Michael Roberts (July 10, 2015), "Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs Recruiting Military? Report Cites Colorado Murder" Archived October 6, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Westword

- ^ "Los Angeles Gangs and Hate Crimes" Archived July 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Police Law Enforcement Magazine, February 29, 2008

- ^ Montaldo, Charles (2014). "The Aryan Brotherhood: Profile of One of the Most Notorious Prison Gangs". About.com. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ^ Rhian Daly (May 1, 2019), Rival gangs Crips And Bloods talk "historic" coming together following Nipsey Hussle's murder" Archived November 12, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, NME

- ^ Sam Quinones (October 18, 2007), "Gang rivalry grows into race war" Archived January 13, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times

- ^ Brad Hamilton (October 28, 2007), "Gangs of New York" Archived February 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, New York Post

- ^ "Gang Information" Archived February 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, bethlehem-pa.gov (2019)

- ^ People v. Parsley Archived January 14, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Court Listener (August 11, 2016)

- ^ Herbert C. Covey (2015), Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture Archived April 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Not on our turf: California gangs create havoc here",[permanent dead link], Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 28, 1994.

- ^ "Bloods Gang Members Sentenced to Life in Prison for Racketeering Conspiracy Involving Murder and Other Crimes" Archived March 18, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Justice (October 27, 2020)

- ^ Ben Ehrenreich (July 21, 1999), "Ganging up in Venice" Archived January 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, LA Weekly

- ^ a b c d U.S. Department of Justice, Crips.

- ^ Failla, Zak (September 9, 2022). "Maryland Gang Member Who Goes By 'Crazy' Sentenced For Assaulting Fellow 'Crip' Behind Bars". Daily Voice. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Meghann, Cuniff (August 8, 2022). "'Boss of Bosses' Crips Gang Leader Sentenced to Decades in Federal Prison for Racketeering Murder Conspiracy". Law & Crime. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles". Inside. National Geographic Channel. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Dunn, William (2008). Boot: An LAPD Officer's Rookie Year in South Central Los Angeles. iUniverse. p. 76. ISBN 9780595468782.

- ^ Stacy Peralta (Director), Stacy Peralta & Sam George (writers), Baron Davis et al. (producer), Steve Luczo, Quincy "QD3" Jones III (executive producer) (2009). Crips and Bloods: Made in America (TV-Documentary). PBS Independent Lens series. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ "Timeline: South Central Los Angeles". PBS (part of the "Crips and Bloods: Made in America" TV documentary). April 21, 2009. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ Sharkey, Betsy (February 6, 2009). "Review: 'Crips and Bloods: Made in America'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Cle Sloan (Director), Antoine Fuqua and Cle Sloan (producer), Jack Gulick (executive producer) (2009). Keith Salmon (ed.). Bastards of the Party (TV-Documentary). HBO. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Stanley Tookie; Smiley, Tavis (2007). Blue Rage, Black Redemption. Simon & Schuster. pp. xvii–xix, 91–92, 136. ISBN 1-4165-4449-6.

- ^ Leonard, Barry (November 2009). National Drug Threat Assessment 2008. DIANE Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4379-1565-5. Archived from the original on April 9, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Finley, Laura L. (October 1, 2018). Gangland: An Encyclopedia of Gang Life from Cradle to Grave [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4408-4474-4. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Vigil, James Diego (November 3, 2021). The Projects: Gang and Non-gang Families in East Los Angeles. University of Texas Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-292-79509-9. Archived from the original on November 25, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2022.

- ^ Leavitt, Fred (September 1, 2004). The Real Drug Abusers. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-585-46674-3. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- ^ a b Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. Holy Fire. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ "The Crips: Prison Gang Profile". Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- ^ =Alliances, Conflicts, and Contradictions in Montreal's Street Gang Landscape, Karine Descormiers and Carlo Morselli, International Criminal Justice Review (October 17, 2020)

- ^ Toronto police, numerous other forces, dismantle 'violent street gang' known as Eglinton West Crips Archived February 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Jessica Patton, Global News (October 29, 2020)

- ^ Covey, Herbert. Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture: A Guide to an American Subculture. p. 9.

- ^ "Gangs Increasing in Military, FBI Says". Military.com. McClatchy-Tribune Information Services. June 30, 2008. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.'s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin's Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ Simpson, Colton (2005). Inside the Crips: Life Inside L.A.'s Most Notorious Gang. St. Martin's Press. pp. 122–124. ISBN 978-0-312-32930-3.

- ^ "Los Angeles-area gang member and longtime pimp gets 40-year federal prison term for sex trafficking of children | ICE". October 8, 2020.

- ^ Capozzoli, Thomas and McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, p. 72. ISBN 1-57444-283-X.

- ^ "War and Peace in Watts" Archived April 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (July 14, 2005). LA Weekly. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Harris, Donnie (October 2004). Gangland. Holy Fire. ISBN 9780976111245.

- ^ Hunt, Darnell; Ramon, Ana-Christina (May 2010). Black Los Angeles. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814773062.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Garrison, Jessica; Mejia, Brittany; Chabria, Anita (April 6, 2022). "At least five shooters involved in Sacramento massacre, gang ties likely, police say". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ Gruver, Mead (June 20, 2025). "Teen charged with 4 counts of murder in Utah carnival shooting". AP News. Retrieved September 7, 2025.

General

[edit]- Leon Bing (1991). Do or Die: America's Most Notorious Gangs Speak for Themselves. Sagebrush. ISBN 0-8335-8499-5

- Yusuf Jah, Sister Shah'keyah, Ice-T, UPRISING : Crips and Bloods Tell the Story of America's Youth In The Crossfire, ISBN 0-684-80460-3

- Capozzoli, Thomas og McVey, R. Steve (1999). Kids Killing Kids: Managing Violence and Gangs in Schools. St. Lucie Press, Boca Raton, Florida, side. 72 ISBN 1-57444-283-X

- National Drug Intelligence Center (2002). Drugs and Crime: Gang Profile: Crips (PDF). U.S. Department of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2009. Product no. 2002-M0465-001.

- Shakur, Sanyika (1993). Monster: The Autobiography of an L.A. Gang Member, Atlantic Monthly Pr, ISBN 0-87113-535-3

- Colton Simpson, Ann Pearlman, Ice-T (Foreword) (2005). Inside the Crips : Life Inside L.A.'s Most Notorious Gang (HB) ISBN 0-312-32929-6

- Smith, Debra; Whitmore, Kathryn F. (2006). Literacy and Advocacy in Adolescent Family, Gang, School, and Juvenile Court Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-5599-8.

- Stanley Tookie Williams (2005). Blue Rage, Black Redemption: A Memoir (PB) ISBN 0-9753584-0-5

External links

[edit]- PBS Independent Lens program on South Los Angeles gangs

- Snopes Urban Legend – The origin of the name Crips