Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Cryptomonad.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cryptomonad

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Cryptomonad

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

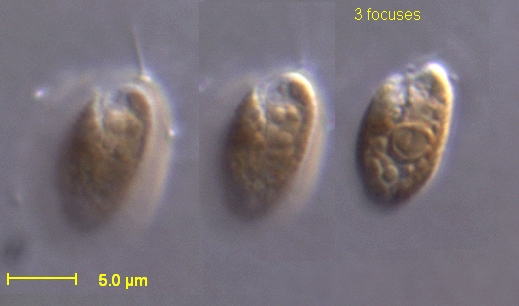

Cryptomonads, also known as cryptophytes, are single-celled biflagellate protists belonging to the phylum Cryptophyta, renowned for their plastids acquired through secondary endosymbiosis of a red alga, which results in chloroplasts surrounded by four membranes.[1] These microscopic eukaryotes, typically ranging from 5 to 50 μm in length, exhibit a bean-shaped or flattened asymmetry and are motile via two unequal flagella inserted into an anterior groove.[1] Found ubiquitously in marine, brackish, and freshwater environments worldwide, cryptomonads play key roles in aquatic ecosystems as primary producers and grazers.[2]

Morphologically, cryptomonads feature a proteinaceous periplast covering their cell surface, which provides structural support and includes ejectisomes—organelles that discharge threads for defense against predators.[1] Photosynthetic species possess H-shaped plastids containing chlorophylls a and c, alloxanthin, and distinctive phycobiliproteins such as phycoerythrin or phycocyanin, enabling efficient light harvesting in low-light conditions typical of deeper waters.[1] A unique vestige of their endosymbiotic origin is the nucleomorph, a reduced nucleus of the engulfed red alga located between the inner and outer plastid membrane pairs, with a genome of less than 1 Mb encoding around 500 genes across three chromosomes.[1] While most cryptomonads are photosynthetic autotrophs, some are heterotrophic or mixotrophic, ingesting prey via phagocytosis, and a few have lost their plastids entirely.[2] Reproduction occurs primarily through asexual binary fission, though evidence suggests sexual processes in certain species.[2]

Ecologically, cryptomonads contribute significantly to phytoplankton communities, particularly in cooler, nutrient-rich waters where their phycobiliproteins enhance red light absorption.[3] Their diversity, with over 20 genera such as Cryptomonas, Rhodomonas, and Chroomonas, reflects adaptations to varying salinities and light regimes, and they serve as important links in food webs, supporting zooplankton and higher trophic levels.[2] Classification relies heavily on ultrastructural features like flagellar apparatus and periplast composition due to their unicellular nature and small size.[4]

From an evolutionary perspective, cryptomonads are pivotal model organisms for understanding complex endosymbioses, as their nucleomorph provides direct evidence of eukaryote-eukaryote integration and subsequent genome reorganization.[2] Phylogenetic analyses place them among heterotrophic protists, potentially related to groups like katablepharids, highlighting their role in tracing the origins of photosynthetic organelles in chromalveolates.[1] Studies of their plastid and nucleomorph genomes continue to illuminate transitions between photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic lifestyles in protists.[1]

Morphology and Cell Structure

Periplast and Ejectisomes

The periplast of cryptomonads is a distinctive protein-rich cell covering that envelops the plasma membrane, consisting of an outer surface periplast component (SPC) and an inner periplast component (IPC) that sandwich the membrane itself. This layered structure provides structural rigidity and protection to the cell, with the IPC typically formed from discrete proteinaceous plates—often rectangular or hexagonal—arranged in longitudinal rows across the cell surface. These plates are anchored to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane by transmembrane particles, ensuring close apposition and contributing to the flattened, dorsoventral asymmetry characteristic of cryptomonad morphology.[5][1][2] The composition and arrangement of periplast components vary significantly among species, reflecting taxonomic diversity within the group. In genera like Cryptomonas, the IPC plates are generally smooth and unornamented, forming a uniform covering, whereas other species such as Chroomonas exhibit more elaborate rectangular plates or even sheet-like IPCs without discrete plates. The SPC, in contrast, may comprise self-assembling crystalline plates, rosette scales, or a fibrous coat derived from high-molecular-weight glycoproteins synthesized in the endomembrane system; these outer elements develop through anamorphic growth zones during the cell cycle and can be visualized distinctly via electron microscopy. Such variations not only aid in species identification but also adapt the periplast to environmental stresses, enhancing overall cell integrity without a true cell wall.[5][2] Ejectisomes, also termed extrusomes or trichocysts, are hallmark defensive organelles unique to cryptomonads, housed in vesicles beneath the periplast and concentrated along the cell's furrow or sulcus. These structures consist of two unequally sized, tightly coiled ribbon-like tapes—approximately 100–200 nm wide when coiled—enclosed within a membrane, with larger ejectisomes measuring 500–700 nm in diameter and smaller ones 250 nm. Formed in the Golgi apparatus, they discharge rapidly in response to stimuli such as mechanical disturbance, pH shifts, osmolarity changes, or light fluctuations, everting into elongated threads (up to 7 μm for large ones) that release mucilage or propel the cell backward in a jerky motion. This extrusion mechanism serves primarily for predator deterrence or temporary attachment, with ejectisomes numbering in the dozens to hundreds per cell and exhibiting genus-specific variations in size, coiling, and arrangement.[6][1][2]Chloroplasts and Nucleomorph

Cryptomonad chloroplasts are typically single or paired organelles per cell, often exhibiting an H-shaped configuration with lobes extending along the cell's length. These plastids are bounded by four membranes, the outermost of which is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum, reflecting their secondary endosymbiotic origin. Internally, the thylakoids are organized into unstacked pairs or lamellae, lacking grana formations, and contain chlorophylls a and c₂ as primary photosynthetic pigments, alongside the carotenoid alloxanthin. Unique to cryptomonads among algae, the chloroplasts house phycobiliproteins such as phycoerythrin or phycocyanin, which are sequestered within the intrathylakoid lumen rather than forming phycobilisomes. These biliproteins, including Cr-PC (a phycocyanin-like complex) or Cr-PE (phycoerythrin), absorb green wavelengths of light (approximately 490–570 nm), complementing chlorophyll absorption and facilitating efficient energy transfer to photosystem II in shaded aquatic environments. The pigment composition imparts varied cell colors, from blue-green to red or brown, depending on the dominant biliprotein. The nucleomorph, a vestigial nucleus of the engulfed red algal endosymbiont, resides in the periplastidial space between the second and third chloroplast membranes. This double-membraned organelle, with pores resembling nuclear pores, contains a compact genome across three chromosomes totaling 0.49–0.84 megabases, encoding approximately 466–518 protein-coding genes primarily for transcription, translation, and plastid functions, including its own rRNA operons and ribosomes. The nucleomorph's position varies by species, often embedded in a pyrenoid invagination or appressed to the inner chloroplast envelope.[7][7] While most cryptomonads are photosynthetic, some species, such as Chilomonas paramecium, are colorless and heterotrophic, having lost functional chloroplasts through gene degradation in the nucleomorph and plastid genomes but retaining a reduced nucleomorph with ~17–19 plastid-targeted genes. These non-photosynthetic forms highlight the evolutionary persistence of the endosymbiotic remnant despite the absence of phototrophy.[7][7]Flagella and Motility

Cryptomonads possess two heterokont flagella of unequal length, inserted subapically into a ventral furrow or gullet structure known as the vestibulum.[1] The anterior flagellum, typically longer and directed forward, serves primarily for propulsion, while the posterior flagellum, shorter and trailing backward, facilitates steering and stability.[6] Both flagella measure approximately 15–20 μm in length and are adorned with fine hairs called mastigonemes, which are rigid, bipartite structures consisting of tubular shafts with terminal filaments and associated scales measuring 140–170 nm across.[8][6] The longer flagellum usually bears two unilateral rows of these mastigonemes, spaced about 240–825 nm apart, whereas the shorter flagellum has one row, enhancing hydrodynamic drag and propulsion efficiency.[8] Motility in cryptomonads is achieved through coordinated flagellar beating that generates a rotary or helical swimming trajectory, with the anterior flagellum pulling the cell forward in a breaststroke-like motion while the posterior flagellum modulates direction.[1][8] This pattern allows for smooth forward progression and rapid reorientation via two-dimensional beating, enabling the cell to reverse direction by altering flagellar orientation without thrust reversal.[8] The mastigonemes contribute to these dynamics by increasing drag on the recovery stroke and thrust on the power stroke, resulting in swimming speeds on the order of 100–200 μm/s in active cells.[8] Under stress, such as predator encounter, ejectisomes can discharge to produce jerky backward propulsion, supplementing flagellar movement.[6] The flagella also enable sensory functions, particularly in detecting environmental cues for directed motility.[9] Phototaxis is mediated by a dual-rhodopsin system in the flagella, where light absorption at wavelengths around 450–500 nm triggers photoelectric currents that modulate beating frequency and direction, allowing positive orientation toward light sources.[9] Similarly, the flagella facilitate chemotaxis by sensing nutrient gradients, adjusting swimming paths to optimize foraging in nutrient-rich areas. Across species, variations in flagellar structure include different appendage arrangements, such as single rows of mastigonemes on both flagella or curved spikes on the shorter one, which may fine-tune motility for specific ecological niches.[10]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Asexual Reproduction

Asexual reproduction in cryptomonads primarily occurs through binary fission, a process of longitudinal cell division that begins at the posterior end of the cell and proceeds anteriorly, resulting in two genetically identical daughter cells.[11] This mode of reproduction is the dominant mechanism for population expansion in both culture and natural environments, enabling rapid clonal propagation without genetic recombination.[12] Division typically takes place in either haploid or diploid states, varying by species; for instance, diploid forms predominate in nutrient-abundant conditions, while haploid phases may occur during certain life stages.[13] The cell cycle in cryptomonads involves distinct phases coordinated across the nucleus, nucleomorph, and organelles. During the G1 phase, cells undergo growth with a single cup-shaped chloroplast; this is followed by the S phase, where DNA replication occurs in both the nucleus and nucleomorph.[11] Mitosis is open, with the nuclear envelope breaking down during prometaphase, and features an initially extranuclear spindle formed from microtubules originating at the replicated flagellar bases, which migrate anteriorly and enter the nucleus.[14] Flagella duplicate early in prophase, leading to a transient quadriflagellate stage that facilitates motility in daughter cells.[11] The chloroplast divides in preprophase via constriction at the dorsal bridge, while the nucleomorph undergoes division through sequential invagination of its envelope membranes without microtubule involvement, ensuring equitable segregation to each daughter cell.[11] Cytokinesis completes the process by furrowing, separating the cells.[14] Binary fission is favored under nutrient-rich conditions, such as elevated inorganic nitrogen levels following environmental inputs like rainfall, which promote rapid population growth and can lead to blooms in aquatic habitats.[15] For example, in the species Cryptomonas, division occurs every 12-24 hours under optimal laboratory conditions of moderate light (approximately 50-100 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹) and temperatures around 15-20°C, allowing doubling times that support dense cultures.[16] This efficiency underscores the role of asexual reproduction in enabling cryptomonads to quickly exploit favorable ecological niches.[17]Sexual Reproduction

Sexual reproduction in cryptomonads is rare, with observations limited to a few genera including Cryptomonas and Chroomonas, where it contrasts with the predominant asexual mode of binary fission.[18] In documented cases, vegetative cells function as isogametes, fusing in an isogamous manner without significant morphological differentiation between mating types.[19] Plasmogamy initiates at the posterior end of one gamete and the mid-ventral region of the other, often involving a pointed protuberance, leading to a transient quadriflagellate cell that becomes spherical and settles.[19] Karyogamy follows, with nuclear membranes breaking down and the haploid nuclei fusing directly to form a diploid zygotic nucleus, while the two nucleomorphs and chloroplasts remain distinct but enclosed together in a shared periplastidial compartment.[19] The zygote develops a multi-layered wall and enters a resistant resting stage, resembling a palmelloid form, prior to meiosis.[20] Cryptomonads follow a haplontic life cycle, characterized by a prolonged haploid vegetative phase; the diploid state is transient within the zygote, where meiosis restores haploidy and generates genetic variation through recombination.[19][21] This process enhances heterozygosity and adaptability in environmentally variable habitats, though direct evidence remains sparse.[13] In some species like Proteomonas sulcata, dimorphic forms alternate between haploid and diploid stages, suggesting potential variations in cycle expression.[21]Classification and Taxonomy

Historical Development

The first descriptions of cryptomonads date to 1831, when Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg observed biflagellate unicellular organisms in freshwater samples and established the genus Cryptomonas as part of his studies on Infusoria, noting their distinctive flattened shape and pigmentation.[22] These early observations, based on light microscopy, highlighted features such as the cells' anterior gullet and flagellar arrangement, though Ehrenberg initially grouped them with other microscopic animals.[23] Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, botanists increasingly treated cryptomonads as algae, with Alfred Pascher's 1914 classification in Die Süsswasser-Flora Deutschlands, Österreichs und der Schweiz dividing them into motile and non-motile subgroups based on thallus organization and habitat preferences.[23] By the mid-20th century, improved light microscopy techniques, as detailed in Georg Huber-Pestalozzi's 1950 compendium Das Phytoplankton des Süsswassers, revealed finer details of their flagella, pigments like alloxanthin, and nutritional modes, solidifying their placement among photosynthetic protists while resolving earlier debates over animal-like versus plant-like traits.[4] A pivotal advance came in the 1960s with the application of electron microscopy, which first confirmed the periplast—a complex surface layer of plates and scales—as a defining ultrastructural feature, as reported in studies on species like Cryptomonas ovata.[24] This period marked the transition to recognizing cryptomonads as a distinct protist group, culminating in Pierre Bourrelly's 1970 classification in Les Algues d'Eau Douce, which integrated these findings into a cohesive taxonomic framework emphasizing their biflagellate nature and ecological roles.[23] These developments provided the morphological foundation for subsequent molecular refinements in taxonomy.Modern Taxonomic Framework

The modern taxonomic framework of cryptomonads places them within the phylum Cryptophyta, which is divided into two classes: Cryptophyceae, encompassing photosynthetic forms with plastids, and Goniomonadea, comprising non-photosynthetic, heterotrophic lineages.[25] The class Cryptophyceae includes orders such as Cryptomonadales and Pyrenomonadales, characterized by the presence of chloroplasts and associated pigments, while the class Goniomonadea contains the order Goniomonadales, distinguished by the absence of plastids and reliance on phagotrophy.[26] This hierarchical structure integrates ultrastructural features, such as periplast composition and flagellar apparatus, with biochemical traits like pigment profiles. Non-photosynthetic forms, including goniomonads, are firmly included within Cryptophyta, while katablepharids are recognized as a distant sister group within the broader infrakingdom Cryptista but excluded from the core cryptophyte assemblage.[27] The core group of Cryptophyta encompasses approximately 230 species across more than 20 genera, reflecting a compact but diverse radiation primarily in aquatic environments.[28][29] Molecular markers, particularly small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) genes from both nuclear and nucleomorph genomes, alongside plastid-encoded genes such as psbA, have been pivotal in defining clades and supporting taxonomic emendations.[30] These analyses have facilitated the separation of photosynthetic and heterotrophic lineages, refining generic boundaries and revealing cryptic diversity, such as within Cryptomonas, where emendations distinguish species based on sequence divergences.[31] The foundational revision by Clay et al. (1999) established key aspects of this framework using integrated ultrastructural, biochemical, and early molecular data.[32] Subsequent updates in the 2010s, incorporating internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) rDNA sequencing aligned to secondary structures, have further resolved species-level taxonomy, confirming monophyly of key genera and identifying novel lineages without altering the overarching class and order structure.[33]Diversity of Genera and Species

The Cryptophyta, commonly known as cryptomonads, exhibit a moderate level of described taxonomic diversity, with approximately 230 species recognized across more than 20 genera, though molecular studies suggest substantial undescribed variation within this phylum.[28][29] This diversity is characterized by variations in pigmentation, nutritional modes, and habitat preferences, with genera often differentiated by the presence or absence of plastids and the composition of periplast plates. The genus Cryptomonas represents one of the most species-rich groups, primarily inhabiting freshwater environments and featuring brownish pigmentation due to phycobiliproteins; it includes approximately 100 described species, with higher diversity observed in temperate and tropical inland waters.[22] For instance, a comprehensive survey in Vietnam identified 24 Cryptomonas species from 122 strains, underscoring elevated freshwater diversity in certain regions.[30] Recent taxonomic work has added to this, describing six new species—C. matvienkoae, C. furtiva, C. paludosa, C. ursina, C. vietnamica, and C. vietnamensis—from Vietnamese freshwater habitats in 2022, based on combined morphological and molecular analyses.[30] In contrast, marine forms show distinct adaptations, such as the red-pigmented genus Rhodomonas, which is predominantly oceanic and includes several species valued for their role in aquaculture feeds due to high lipid content.[34] Other notable marine genera include Teleaulax, comprising a few small, biflagellate species that contribute to nanoplankton communities.[35] Colorless heterotrophs like Chilomonas, which lack functional plastids and rely on bacterivory, are mostly freshwater dwellers with limited species diversity, exemplified by C. paramecium.[36] Rare or specialized genera highlight further morphological variation; Goniomonas, the sole member of the aplastidic order Goniomonadales, is heterotrophic and lacks chloroplasts entirely, occurring in both freshwater and marine settings. A 2025 revision described seven new species and emended descriptions of existing ones, expanding known diversity in this genus.[37][38] Similarly, Plagioselmis features nanoplanktonic species such as P. prolonga, which exhibit dimorphic life stages and are widespread in coastal waters, reflecting adaptive plasticity in size and form.[39] Overall, while freshwater genera dominate in species richness, marine and heterotrophic forms underscore the phylum's ecological breadth.[31]Evolutionary History

Endosymbiotic Origins

Cryptomonads possess complex plastids that originated via secondary endosymbiosis, in which a heterotrophic eukaryotic host engulfed a photosynthetic red alga approximately 1.26 billion years ago. This event integrated the red algal plastid into the host cell, resulting in a four-membrane-bound organelle where the outermost membranes derive from the host's endomembrane system and the inner two from the original red algal chloroplast envelope. The engulfed red alga's nucleus was not fully eliminated but reduced to a vestigial structure known as the nucleomorph, while the majority of its genes were transferred to the host's nucleus through endosymbiotic gene transfer, enabling coordinated control of the plastid by the host.[40][41] Strong evidence for this red algal origin comes from the structure and genetics of the cryptomonad plastid and nucleomorph. The four-membrane configuration is a hallmark of secondary plastids in chromists, and phylogenetic analyses of plastid genes such as rbcL and psaA confirm their affinity to red algae. The nucleomorph genome, exemplified by that of Guillardia theta, spans 551 kilobase pairs across three chromosomes and encodes 486 proteins, many of which show clear red algal ancestry, including housekeeping genes and components for plastid protein import. This genome's compact, gene-dense nature (one gene per 977 base pairs) reflects extensive gene loss and relocation to the host nucleus.[40][42] A distinctive feature of cryptomonad plastids is the retention of the nucleomorph, which sets them apart from other chromists like haptophytes and stramenopiles that lost this structure after the shared endosymbiotic event. Additionally, cryptomonads inherited phycobiliproteins—pigments such as phycoerythrin—from their red algal ancestor, which are attached to thylakoid membranes rather than organized into phycobilisomes as in free-living red algae, aiding in light harvesting in low-light environments. Recent studies debate whether this secondary endosymbiosis represents a single event in a common chromist ancestor or independent acquisitions; while a 2024 analysis supports a single origin approximately 1.26 billion years ago predating the divergence of cryptophytes from haptophytes and stramenopiles (estimated at around 1.14 billion years ago), an alternative 2024 model proposes separate endosymbioses for cryptophytes (~1.53 billion years ago) and other chromalveolates.[40][43][44]Phylogenetic Relationships

Cryptomonads, also known as cryptophytes, occupy a distinct position within the Diaphoretickes supergroup of the eukaryotic tree of life, where the Cryptista clade—encompassing cryptomonads and their sister group, the katablepharids—forms a close relationship with haptophytes.[45] This arrangement aligns with broader formulations of Hacrobia, which groups cryptomonads alongside haptophytes and certain other lineages, although the monophyly of Hacrobia remains contentious due to inconsistent support across datasets.[46] Some earlier phylogenomic reconstructions placed cryptomonads in sister relation to haptophytes and stramenopiles within an expanded Chromalveolata, but contemporary multi-gene analyses favor their integration into Diaphoretickes as a deeply branching algal lineage.[47] Phylogenetic support derives primarily from nuclear-encoded small subunit ribosomal RNA (SSU rRNA) sequences, which reveal a deep divergence of cryptomonads from other eukaryotic groups while affirming their monophyly.[48] Complementary plastid phylogenies, based on multi-gene datasets, unequivocally trace the origin of their complex plastids to a secondary endosymbiosis involving a red alga from the stem lineage of Rhodophytina.[49] These molecular markers highlight the ancient integration of the red algal symbiont, distinguishing cryptomonads from primary plastid-bearing algae like those in Archaeplastida. Ongoing debates center on the precise inclusion of katablepharids within Cryptista and evidence for independent losses of photosynthesis across non-photosynthetic lineages, which complicate interpretations of ancestral character states.[46] A 2023 phylogenomic study employing ultraconserved elements from nuclear, nucleomorph, and plastid genomes across 91 cryptomonad strains robustly upholds their status as a distinct phylum, while molecular clock estimates from related analyses indicate divergence from other chromist groups approximately 1.14 billion years ago.[50][40][49]Ecology and Distribution

Habitats and Global Distribution

Cryptomonads inhabit a diverse array of aquatic environments, primarily freshwater systems such as lakes and rivers, as well as marine settings including coastal zones and the open ocean.[51] They are also common in brackish waters, reflecting their adaptability to varying ionic compositions.[52] These protists particularly favor low-light conditions, thriving in shaded microenvironments like those beneath ice covers in polar regions or under vegetative canopies in temperate lakes, where reduced irradiance supports their phycobiliprotein-mediated photosynthesis.[51] The global distribution of cryptomonads is cosmopolitan, spanning from polar latitudes, such as Arctic lakes and seas, to tropical oceans and inland waters.[51] They occur worldwide in nearly all types of water bodies, from saline oceans to freshwater puddles, with notable abundance in temperate eutrophic lakes where nutrient enrichment promotes their growth.[12] This broad occurrence underscores their ecological versatility across climatic zones.[53] Cryptomonads demonstrate tolerance to a wide environmental gradient, flourishing in temperatures ranging from near 0°C in cold polar waters to 25°C in warmer temperate and subtropical systems.[54] They accommodate salinities from 0 ppt in freshwater to 35 ppt in fully marine habitats, enabling persistence across estuarine gradients.[55] For pH, they prefer slightly alkaline conditions (above 7.5) but tolerate values between 6 and 9, often dominating in buffered, productive waters.[56] Within these environments, cryptomonads predominantly occupy planktonic niches as free-floating cells in the water column, contributing to phytoplankton assemblages.[12] Some species, however, are benthic, adhering to sediments or substrates in shallow aquatic zones.[57] Additionally, certain cryptomonads engage in symbiotic associations with freshwater sponges, where they provide nutritional benefits within host tissues.[58]Ecological Roles

Cryptomonads serve as key primary producers in aquatic ecosystems, particularly in freshwater and coastal marine environments where they contribute substantially to carbon fixation. Their ability to thrive in dim light conditions is facilitated by phycobilins, accessory pigments that enhance light harvesting in the green spectrum, allowing efficient photosynthesis under low irradiance levels often found in deeper or shaded waters.[1] In lakes, cryptomonads can form a significant portion of phytoplankton biomass.[59] This productivity supports overall ecosystem carbon dynamics, with documented increases in primary production rates in fertilized lake systems dominated by cryptomonads.[60] In trophic interactions, cryptomonads occupy multiple levels within food webs, functioning both as prey and predators. They are highly nutritious and digestible for herbivorous zooplankton, including species like Daphnia pulicaria and D. thorata, which exhibit strong growth when feeding on cryptomonads such as Cryptomonas erosa.[60] Heterotrophic and mixotrophic forms, such as Goniomonas species, actively consume bacteria, positioning cryptomonads as bacterivores that link microbial loops to higher trophic levels.[61] This dual role enhances energy transfer efficiency, as mixotrophic cryptomonads combine photosynthesis with phagotrophy to exploit diverse resources.[62] Recent studies as of 2025 have further elucidated cryptophyte community assembly in river-estuary-coast continua, revealing deterministic processes like environmental filtering that shape diversity and ecological roles in connected ecosystems.[61] Cryptomonads play a vital part in nutrient cycling by releasing dissolved organic matter through grazing and excretion, which facilitates the remineralization of nitrogen and phosphorus in aquatic systems.[60] Their mixotrophic capabilities allow them to acquire nutrients via both dissolved uptake and bacterial predation, thereby recycling bioavailable forms of these elements and supporting phytoplankton succession.[62] Zooplankton grazing on cryptomonads further promotes nutrient regeneration, creating feedback loops that sustain productivity in nutrient-limited environments.[60] Occasional blooms of cryptomonads occur in stratified lakes, where they can dominate phytoplankton assemblages and influence ecosystem processes. These events elevate local oxygen production during peak growth but may lead to depletion upon senescence, affecting water quality and the base of fish food chains by providing abundant prey resources.[63] Such blooms underscore their role in maintaining biodiversity and trophic stability in temperate freshwater systems.[61]Interactions and Seasonality

Cryptomonads engage in various biotic interactions that influence their survival and distribution in aquatic ecosystems. They are frequently preyed upon by small planktonic ciliates, such as those in the genus Balanion, which exhibit species-specific feeding preferences and can exert significant predation pressure on cryptomonad populations, particularly in metalimnetic layers where Cryptomonas species aggregate.[64][65] Rotifers, including species like Keratella and Synchaeta, also graze heavily on small cryptophytes (<1,000 μm³), contributing to top-down control in both freshwater and marine environments, with grazing rates often leading to rapid declines in cryptomonad abundance during periods of high rotifer activity.[66][67] In response to such predation, cryptomonads deploy defensive ejectisomes, extrusome-like structures that discharge to deter herbivores upon disturbance.[68] Competition with diatoms is another key interaction, where shifts in dominance occur based on environmental conditions; for instance, in Antarctic coastal waters, cryptomonads prevail under shallower mixed layers and lower salinities, while diatoms outcompete them during deeper mixing and warmer periods.[69] A notable symbiotic relationship involves viruses within cryptomonad cells, as demonstrated in a 2023 study of Cryptomonas gyropyrenoidosa, where a single cell hosts two bacterial endosymbionts (Megaira polyxenophila and another) along with a bacteriophage that infects one endosymbiont, forming a complex intracellular community that highlights viral mediation in endosymbiotic dynamics.[70] Seasonal patterns of cryptomonad abundance vary by latitude and are closely tied to physical mixing and nutrient availability. In temperate lakes, populations often peak during spring and autumn turnover events, when destratification mixes nutrient-rich hypolimnetic waters with the epilimnion, favoring cryptomonad growth; for example, in mesotrophic systems, abundances surge as temperatures moderate between 10–20°C.[71][51] In tropical regions, cryptomonads maintain more consistent year-round presence, with fluctuations driven by pulsed nutrient inputs from rainfall or upwelling rather than thermal stratification, allowing persistent low-level blooms under stable warm conditions (25–30°C).[72] Responses to temperature and nutrient pulses are pronounced; elevated temperatures up to an optimum (around 20–25°C for many species) enhance growth rates, while sudden nutrient enrichments, such as nitrate spikes, trigger rapid proliferation, though excesses can shift community structure toward competitors.[66][73] Population dynamics of cryptomonads are characterized by episodic blooms and grazing-induced declines, modulated by trophic conditions. In eutrophic basins, such as those in Lake Taihu, China, cryptomonads form notable blooms during transitional seasons, with a 2015 study revealing higher densities and prolonged peaks in mesotrophic to eutrophic zones compared to oligotrophic areas, where nutrient gradients dictate biomass variations up to 10-fold.[74] Grazing by zooplankton, particularly ciliates and rotifers, frequently causes sharp declines, with rates removing 5–25% of standing cryptomonad biomass daily in stratified lakes, leading to synchronous crashes during peak predator abundances.[65][75] Cryptomonads hold relevance for human activities, serving as bioindicators of water quality due to their sensitivity to nutrient enrichment; elevated abundances often signal mesoeutrophic conditions and inorganic nitrogen pulses, as observed in riverine systems where blooms correlate with deteriorating physicochemical parameters.[76][62] Their high lipid content, reaching 22% dry weight in species like Cryptomonas sp., positions them as promising feed additives in aquaculture, providing essential polyunsaturated fatty acids (e.g., 20:5ω3) that enhance larval nutrition and replace fish oils sustainably.[77][78]References

- https://species.wikimedia.org/wiki/Cryptophyta