Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cryptophyceae

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

| Cryptophyceae | |

|---|---|

| |

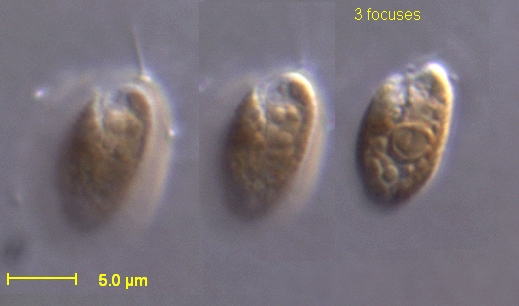

| Rhodomonas salina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Cryptista |

| Superclass: | Cryptomonada |

| Class: | Cryptophyceae |

| Orders | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Cryptophyceae are a class of algae,[1] most of which have plastids. About 230 species are known,[2] and they are common in freshwater, and also occur in marine and brackish habitats. Each cell is around 10–50 μm in size and flattened in shape, with an anterior groove or pocket. At the edge of the pocket there are typically two slightly unequal flagella.

Some exhibit mixotrophy.[3]

Characteristics

[edit]

Cryptophytes are distinguished by the presence of characteristic extrusomes called ejectosomes or ejectisomes, which consist of two connected spiral ribbons held under tension.[4] If the cells are irritated either by mechanical, chemical or light stress, they discharge, propelling the cell in a zig-zag course away from the disturbance. Large ejectosomes, visible under the light microscope, are associated with the pocket; smaller ones occur underneath the periplast, the cryptophyte-specific cell surrounding.[5][6]

Except for Chilomonas, which has leucoplasts, cryptophytes have one or two chloroplasts. These contain chlorophylls a and c, together with phycobiliproteins and other pigments, and vary in color (brown, red to blueish-green). Each is surrounded by four membranes, and there is a reduced cell nucleus called a nucleomorph between the middle two. This indicates that the plastid was derived from a eukaryotic symbiont, shown by genetic studies to have been a red alga.[7] However, the plastids are very different from red algal plastids: phycobiliproteins are present but only in the thylakoid lumen and are present only as phycoerythrin or phycocyanin. In the case of "Rhodomonas" the crystal structure has been determined to 1.63Å;[8] and it has been shown that the alpha subunit bears no relation to any other known phycobiliprotein.

A few cryptophytes, such as Cryptomonas, can form palmelloid stages, but readily escape the surrounding mucus to become free-living flagellates again. Some Cryptomonas species may also form immotile microbial cysts–resting stages with rigid cell walls to survive unfavorable conditions. Cryptophyte flagella are inserted parallel to one another, and are covered by bipartite hairs called mastigonemes, formed within the endoplasmic reticulum and transported to the cell surface. Small scales may also be present on the flagella and cell body. The mitochondria have flat cristae, and mitosis is open; sexual reproduction has also been reported.

The group have evolved a whole range of light-absorbing pigments, called phycobilins, which are able to absorb wavelengths that are not accessible to other plants or algae, allowing them to live in a variety of different ecological niches.[9] An ability that originates from the evolution of a unique light‐harvesting antenna complex derived from two relict parts of the red algal phycobilisome, which was completely dismantled during the endosymbiotic process.[10]

While cryptophytes are usually seen as asexual, sexual reproductions do occur; both haploid and diploid forms have been found. The two species Teleaulax amphioxeia and Plagioselmis prolonga are now considered to be the same species, where T. amphioxeia is the diploid form and P. prolonga is the haploid form. The diploid form is most common when there are more nutrients in the water. Two haploid cells will often fuse to form a diploid cell, mixing their genes.[11]

Classification

[edit]

The first mention of cryptophytes appears to have been made by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1831,[12] while studying Infusoria. Later, botanists treated them as a separate algae group, class Cryptophyceae or division Cryptophyta, while zoologists treated them as the flagellate protozoa order Cryptomonadina. In some classifications, the cryptomonads were considered close relatives of the dinoflagellates because of their (seemingly) similar pigmentation, being grouped as the Pyrrhophyta. There is considerable evidence that cryptophyte chloroplasts are closely related to those of the heterokonts and haptophytes, and the three groups are sometimes united as the Chromista. However, the case that the organisms themselves are closely related is not very strong, and they may have acquired plastids independently. Currently they are discussed to be members of the clade Diaphoretickes and to form together with the Haptophyta the group Hacrobia. Parfrey et al. and Burki et al. placed Cryptophyceae as a sister clade to the green algae.[13][14]

One suggested grouping is as follows: (1) Cryptomonas, (2) Chroomonas/Komma and Hemiselmis, (3) Rhodomonas/Rhinomonas/Storeatula, (4) Guillardia/Hanusia, (5) Geminigera/Plagioselmis/Teleaulax, (6) Proteomonas sulcata, (7) Falcomonas daucoides.[15]

- Class Cryptophyceae Fritsch 1937 [Cryptomonadea Stein 1878 emend. Schoenichen 1925]

- Genus Wysotzkia Lemmermann 1899

- Genus Urgorri Laza-Martinez 2012

- Order Tetragonidiales Kristiansen 1992

- Family Tetragonidiaceae Bourelly ex Silva1980

- Genus Bjornbergiella Bicudo 1966

- Genus Tetragonidium Pascher 1914

- Family Tetragonidiaceae Bourelly ex Silva1980

- Order Pyrenomonadales Novarino & Lucas 1993

- Family Baffinellaceae Daugbjerg & Norlin 2018[16]

- Genus Baffinella Norlin & Daugbjerg 2018

- Family Chroomonadaceae Clay, Cugrens & Lee 1999

- Genus ?Smithimastix Skvortzov 1969 [Smithiella Skvortzov 1968 nom. illeg.]

- Genus Chroomonas Hansgirg 1885

- Genus Falcomonas Hill 1991

- Genus Hemiselmis Parke 1949

- Genus Komma Hill 1991

- Genus Nodeana Skvortzov 1968

- Genus Planonephros Christensen 1978

- Genus Protochrysis Pascher 1911

- Family Geminigeraceae Clay, Cugrens & Lee 1999

- Genus Geminigera Hill 1991

- Genus Guillardia Hill & Wetherbee 1990

- Genus Phia Özdikmen 2009 [Hanusia Deane et al. 1998 non Cripps 1989]

- Genus Plagioselmis Butcher 1967 ex Novarino, Lucas & Morrall 1994

- Genus Teleaulax Hill 1991

- Family Pyrenomonadaceae Novarino & Lucas 1993

- Genus Proteomonas Hill & Wetherbee 1986

- Genus Rhinomonas Hill & Wetherbee 1988

- Genus Rhodomonas Karsten 1898 [Pyrenomonas Santore 1984]

- Genus Storeatula Hill 1991

- Family Baffinellaceae Daugbjerg & Norlin 2018[16]

- Order Cryptomonadales Pascher 1913

- Family ?Butschliellaceae Skvortzov 1968

- Genus Butschliella Skvortzov 1968

- Genus Skvortzoviella Bourelly 1970

- Family ?Cyathomonadaceae Pringsheim 1944

- Genus Cyathomonas de Fromentel 1874

- Family ?Hilleaceae Pascher 1967

- Genus Calkinsiella Skvortzov 1969

- Genus Hillea Schiller 1925

- Family ?Pleuromastigaceae Bourrelly ex Silva 1980

- Genus ?Opisthostigma Scherfffel 1911

- Genus Pleuromastix Scherffel 1912 non Namyslowski 1913

- Genus Xanthodiscus Schewiakoff 1892

- Family Cryptomonadaceae Ehrenberg 1831 [Campylomonadaceae Clay, Kugrens & Lee 1999; Cryptochrysidaceae Pascher 1931]

- Genus ?Chilomonas Ehrenberg 1831

- Genus ?Protocryptochrysis Skvortzov 1969

- Genus Cryptella Pascher 1929

- Genus Cryptochloris Schiller 1925

- Genus Cryptochrysis Pascher 1911

- Genus Cryptomonas Ehrenberg 1832 [Campylomonas Hill 1991]

- Genus Cyanomastix Lackey 1936

- Genus Isoselmis Butcher 1967

- Genus Kisselevia Skvortzov 1969

- Genus Meyeriella Skvortzov 1968

- Genus Olivamonas Skvortzov 1969

- Genus Protocryptomonas Skvortzov 1969 ex Bicudo 1989

- Family ?Butschliellaceae Skvortzov 1968

References

[edit]- ^ Khan H, Archibald JM (May 2008). "Lateral transfer of introns in the cryptophyte plastid genome". Nucleic Acids Res. 36 (9): 3043–53. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn095. PMC 2396441. PMID 18397952.

- ^ Cryptophyceae - :: Algaebase

- ^ "Cryptophyta - the cryptomonads". Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- ^ Graham, L. E.; Graham, J. M.; Wilcox, L. W. (2009). Algae (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings (Pearson). ISBN 978-0-321-55965-4.

- ^ Morrall, S.; Greenwood, A. D. (1980). "A comparison of the periodic sub-structures of the trichocysts of the Cryptophyceae and Prasinophyceae". BioSystems. 12 (1–2): 71–83. Bibcode:1980BiSys..12...71M. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(80)90039-8. PMID 6155157.

- ^ Grim, J. N.; Staehelin, L. A. (1984). "The ejectisomes of the flagellate Chilomonas paramecium - Visualization by freeze-fracture and isolation techniques". Journal of Protozoology. 31 (2): 259–267. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1984.tb02957.x. PMID 6470985.

- ^ Douglas, S.; et al. (2002). "The highly reduced genome of an enslaved algal nucleus". Nature. 410 (6832): 1091–1096. Bibcode:2001Natur.410.1091D. doi:10.1038/35074092. PMID 11323671.

- ^ Wilk, K.; et al. (1999). "Evolution of a light-harvesting protein by addition of new subunits and rearrangement of conserved elements: Crystal structure of a cryptophyte phycoerythrin at 1.63Å resolution". PNAS. 96 (16): 8901–8906. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.16.8901. PMC 17705. PMID 10430868.

- ^ Callier, Viviane (23 October 2019). "This Type of Algae Absorbs More Light for Photosynthesis Than Other Plants". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Michie, Katharine A.; Harrop, Stephen J.; Rathbone, Harry W.; Wilk, Krystyna E.; Teng, Chang Ying; Hoef-Emden, Kerstin; Hiller, Roger G.; Green, Beverley R.; Curmi, Paul M. G. (March 2023). "Molecular structures reveal the origin of spectral variation in cryptophyte light harvesting antenna proteins". Protein Science. 32 (3) e4586. doi:10.1002/pro.4586. PMC 9951199. PMID 36721353.

- ^ Altenburger, A.; Blossom, H. E.; Garcia-Cuetos, L.; Jakobsen, H. H.; Carstensen, J.; Lundholm, N.; Hansen, P. J.; Moestrup, ø.; Haraguchi, L. (2020). "Dimorphism in cryptophytes—The case of Teleaulax amphioxeia / Plagioselmis prolonga and its ecological implications". Science Advances. 6 (37). Bibcode:2020SciA....6.1611A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb1611. PMC 7486100. PMID 32917704.

- ^ Novarino, G. (2012). "Cryptomonad taxonomy in the 21st century: The first 200 years". Phycological Reports: Current Advances in Algal Taxonomy and Its Applications: Phylogenetic, Ecological and Applied Perspective: 19–52. Retrieved 2018-10-16.

- ^ Parfrey, Laura Wegener; Lahr, Daniel J. G.; Knoll, Andrew H.; Katz, Laura A. (August 16, 2011). "Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (33): 13624–13629. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10813624P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108. PMC 3158185. PMID 21810989.

- ^ Burki, Fabien; Kaplan, Maia; Tikhonenkov, Denis V.; Zlatogursky, Vasily; Minh, Bui Quang; Radaykina, Liudmila V.; Smirnov, Alexey; Mylnikov, Alexander P.; Keeling, Patrick J. (2016-01-27). "Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista". Proc. R. Soc. B. 283 (1823) 20152802. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2802. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4795036. PMID 26817772.

- ^ "Cryptomonads". Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ Daugbjerg, Niels; Norlin, Andreas; Lovejoy, Connie (2018-07-25). "Baffinella frigidus gen. et sp. nov. (Baffinellaceae fam. nov., Cryptophyceae) from Baffin Bay: Morphology, pigment profile, phylogeny, and growth rate response to three abiotic factors" (PDF). J. Phycol. 54 (5): 665–680. doi:10.1111/jpy.12766. ISSN 1529-8817. PMID 30043990. S2CID 51718360. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-12. Retrieved 2019-05-26.