Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Curlew

View on Wikipedia

| Curlew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Long-billed curlew (Numenius americanus) Fishing Pier, Goose Island State Park, Texas | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Numenius Brisson, 1760 |

| Type species | |

| Scolopax arquata Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

|

N. phaeopus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Palnumenius Miller, 1942 | |

The curlews (/ˈkɜːrljuː/) are a group of nine species of birds in the genus Numenius, characterised by their long, slender, downcurved bills and mottled brown plumage. The English name is imitative of the Eurasian curlew's call, but may have been influenced by the Old French corliu, "messenger", from courir, "to run". It was first recorded in 1377 in Langland's Piers Plowman "Fissch to lyue in þe flode..Þe corlue by kynde of þe eyre".[1] In Europe, "curlew" usually refers to one species, the Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata).

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus Numenius was erected by the French scientist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Ornithologie published in 1760.[2] The type species is the Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata).[3] The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus had introduced the genus Numenius in the 6th edition of his Systema Naturae published in 1748,[4] but Linnaeus dropped the genus in the important tenth edition of 1758 and put the curlews together with the woodcocks in the genus Scolopax.[5][6] As the publication date of Linnaeus's sixth edition was before the 1758 starting point of the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, Brisson and not Linnaeus is considered as the authority for the genus.[7] The name Numenius is from Ancient Greek noumenios, a bird mentioned by Hesychius. It is associated with the curlews because it appears to be derived from neos, "new" and mene, "moon", referring to the crescent-shaped bill.[8] The genus now contains nine species:[9]

The following cladogram showing the genetic relationships between the species is based on a molecular phylogenetic study published in 2023.[10]

| Numenius |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

[edit]They are one of the most ancient lineages of scolopacid waders, together with the godwits which look similar but have straight bills.[11] Curlews feed on mud or very soft ground,[12][13] searching for worms and other invertebrates with their long bills. They will also take crabs and similar items.

Distribution

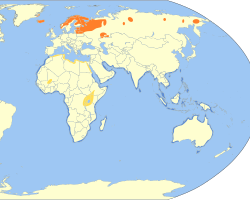

[edit]

Curlews enjoy a worldwide distribution. Most species exhibit strong migratory habits and consequently one or more species can be encountered at different times of the year in Europe, Ireland, Britain, Iberia, Iceland, Africa, Southeast Asia, Siberia, North America, South America and Australasia.

The distribution of curlews has altered considerably in the past hundred years as a result of changing agricultural practices. For instance, Eurasian curlew populations have suffered due to draining of marshes for farmland, whereas long-billed curlews have shown an increase in breeding densities around areas grazed by livestock.[14][15] As of 2019[update], there were only a small number of Eurasian curlews still breeding in Ireland, raising concerns that the bird will become extinct in that country.[16]

The stone-curlews are not true curlews (family Scolopacidae) but members of the family Burhinidae, which is in the same order Charadriiformes, but only distantly related within that.

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasian whimbrel | Numenius phaeopus (Linnaeus, 1758) Five subspecies

|

subarctic Asia and Europe as far south as Scotland

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Hudsonian whimbrel | Numenius hudsonicus Latham, 1790 |

southern North America and South America. It

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Slender-billed curlew † (Last seen in 1995[17])

|

Numenius tenuirostris Vieillot, 1817 |

Russia, Persian gulf, in Kuwait and Iraq.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

EX

|

| Eurasian curlew | Numenius arquata (Linnaeus, 1758) |

temperate Europe and Asia

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT

|

| Long-billed curlew | Numenius americanus Bechstein, 1812 |

central and western North America

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Far Eastern curlew | Numenius madagascariensis (Linnaeus, 1766) |

northeastern Asia, including Siberia to Kamchatka, and Mongolia. coastal Australia, with a few heading to South Korea, Thailand, Philippines and New Zealand | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

EN

|

| Little curlew | Numenius minutus Gould, 1841 |

Australasia, far north of Siberia. | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

LC

|

| Bristle-thighed curlew | Numenius tahitiensis (Gmelin, JF, 1789) |

tropical Oceania, and includes Micronesia, Fiji, Tuvalu, Tonga, Hawaiian Islands, Samoa, French Polynesia and Tongareva, lower Yukon River and Seward Peninsula

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT

|

| Eskimo curlew – †? (Last seen in 1987[18])

|

Numenius borealis (Forster, 1772) |

western Arctic Canada and Alaska, Pampas of Argentina

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

CR

|

The Late Eocene (Montmartre Formation, some 35 mya) fossil Limosa gypsorum of France was originally placed in Numenius and may in fact belong there.[19] Apart from that, a Late Pleistocene curlew from San Josecito Cave, Mexico has been described.[20] This fossil was initially placed in a distinct genus, Palnumenius, but was actually a chronospecies or paleosubspecies related to the long-billed curlew.

The upland sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) is an odd bird which is the closest relative of the curlews.[11] It is distinguished from them by its yellow legs, long tail, and shorter, less curved bill.

References

[edit]- ^ "Curlew". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Vol. 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 48, Vol. 5, p. 311.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 260.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1748). Systema Naturae sistens regna tria naturæ, in classes et ordines, genera et species redacta tabulisque aeneis illustrata (in Latin) (6th ed.). Stockholmiae (Stockholm): Godofr, Kiesewetteri. pp. 16, 26.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

- ^ Allen, J.A. (1910). "Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335. hdl:2246/678.

- ^ "Article 3". International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (4th ed.). London: International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. 1999. ISBN 978-0-85301-006-7.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Sandpipers, snipes, coursers". World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Tan, H.Z.; Jansen, J.J.; Allport, G.A.; Garg, K.M.; Chattopadhyay, B.; Irestedt, M.; Pang, S.E.; Chilton, G.; Gwee, C.Y.; Rheindt, F.E. (2023). "Megafaunal extinctions, not climate change, may explain Holocene genetic diversity declines in Numenius shorebirds". eLife. 12 e85422. doi:10.7554/eLife.85422. PMC 10406428.

- ^ a b Thomas, Gavin H.; Wills, Matthew A.; Székely, Tamás (2004). "A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny". BMC Evol. Biol. 4: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-28. PMC 515296. PMID 15329156.

- ^ "How local farmers in Roscommon and their community got together to conserve a bog and protect rare birds". independent. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ "Reared curlews act like wild counterparts after release in Norfolk". BBC News. 2021-08-19. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Animal World (1977): Vol.6: 518–519. Bay Books, Sydney.

- ^ Cochrane, J. F.; Anderson, S. H. (1987). "Comparison of habitat attributes at sites of stable and declining Long-billed Curlew populations". Great Basin Naturalist. 47: 459–466.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Christian TV Ireland (29 September 2019). Mary Colwell- Interview on the almost extinct Curlew bird in Ireland. Retrieved 29 September 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ BirdLife International (2025). "Numenius tenuirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2025 e.T22693185A205993110. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2025-2.RLTS.T22693185A205993110.en. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ "great Alaska department of fish and game".

- ^ Olson, Storrs L. (1985): Section X.D.2.b. Scolopacidae. In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 174–175. Academic Press, New York.

- ^ Arroyo-Cabrales, Joaquín; Johnson, Eileen (2003). "Catálogo de los ejemplares tipo procedentes de la Cueva de San Josecito, Nuevo León, México" (PDF). Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas. 20 (1): 79–93. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2007-04-29.

Further reading

[edit]- Bodsworth, Fred (1987). Last of the Curlews. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 0-396-09187-3. (originally published in 1954)

- Colwell, Mary (19 April 2018). Curlew Moon. William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-824105-6. OCLC 1035290266.

Curlew

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Phylogeny

Genus Classification

The genus Numenius belongs to the family Scolopacidae within the order Charadriiformes and encompasses species of wading birds known as curlews.[8] These birds are distinguished by their long, slender, decurved bills, mottled brown plumage, and adaptations for shorebird lifestyles, including long legs for wading.[1] The genus was established by French ornithologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760, with the type species being the Eurasian curlew (Numenius arquata), originally classified by Carl Linnaeus as Scolopax arquata in 1758.[9][10] The name Numenius originates from the Ancient Greek noumēnios, denoting a bird—likely the curlew—whose bill curvature evokes the shape of a new moon.[11] Phylogenetic analyses confirm Numenius as a monophyletic group within Scolopacidae, forming sister taxa among curlew species and positioned distantly from other genera in the family, reflecting deep evolutionary divergence.[12][13] This placement underscores the genus's basal role in the Scolopaci subclade, supported by mitochondrial DNA evidence.[13]Species Diversity and Relationships

The genus Numenius encompasses eight species of curlews, all shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae distinguished by their long, decurved bills adapted for probing invertebrates. These species vary in size, ranging from the diminutive Little Curlew (N. minutus) at approximately 30 cm in length to the larger Eurasian Curlew (N. arquata) exceeding 50 cm, with distributions spanning Eurasia, North America, and the Pacific. Two species—the Eskimo Curlew (N. borealis), extinct since the early 20th century, and the Slender-billed Curlew (N. tenuirostris), presumed extinct or critically endangered with no confirmed sightings since 2009—highlight significant losses in diversity, attributed to hunting, habitat alteration, and climate factors.[14][13]| Scientific Name | Common Name | Conservation Status (IUCN, 2023) |

|---|---|---|

| N. minutus | Little Curlew | Least Concern |

| N. borealis | Eskimo Curlew | Extinct |

| N. phaeopus | Whimbrel | Least Concern |

| N. tenuirostris | Slender-billed Curlew | Critically Endangered (possibly extinct) |

| N. arquata | Eurasian Curlew | Near Threatened |

| N. madagascariensis | Far Eastern Curlew | Vulnerable |

| N. americanus | Long-billed Curlew | Least Concern |

| N. tahitiensis | Bristle-thighed Curlew | Vulnerable |

Fossil Record

The genus Numenius first appears in the fossil record during the Middle Miocene, approximately 15–20 million years ago, based on fragmentary remains referred to the genus without assignment to specific species.[19] A notable late Pleistocene specimen, a complete left tarsometatarsus from San Josecito Cave in Nuevo León, Mexico (dated to the Rancholabrean land-mammal age, roughly 250,000–11,700 years ago), was originally described as the holotype of Palnumenius victima but subsequent analysis determined it inseparable from Numenius at the generic level, rendering Palnumenius a junior subjective synonym.[20] This fossil measures 72 mm in length, falling within the lower range of modern male N. americanus (69.8–81.5 mm), with minor morphological differences such as a more abrupt internal cotyla projection and a deeper extensor groove, tentatively interpreted as a temporal or geographic variant of the long-billed curlew (N. americanus).[20] The overall fossil record of Numenius remains sparse, with no well-defined extinct species distinct from extant ones beyond subfossil Holocene remains (e.g., abundant N. tahitiensis bones from pre-human deposits on Moloka'i and Kaua'i, Hawaii, indicating formerly broader distributions).[21] Recent extinctions, such as N. borealis and N. tenuirostris, are documented through historical specimens rather than paleontological fossils.Physical Characteristics

Morphology and Adaptations

Curlews in the genus Numenius are large waders characterized by their elongated bodies, long necks, and notably decurved bills that often exceed half the length of the head and neck combined, with bill lengths ranging from 70 mm in smaller species like the little curlew (N. minutus) to over 150 mm in the long-billed curlew (N. americanus).[22][23] Their legs are proportionally long, typically dull gray or greenish, facilitating wading through shallow water and mudflats without excessive energy expenditure.[4] Plumage is predominantly cryptic, featuring mottled browns, buffs, and streaks on the upperparts and underparts, providing camouflage against grassland and estuarine substrates during breeding and non-breeding seasons.[22] The decurved bill represents a primary morphological adaptation for subsurface foraging, allowing curlews to probe deeply into soft sediments—up to depths beyond 15 cm—to extract burrowing prey such as annelid worms, crustaceans, and bivalves that are inaccessible to straighter-billed shorebirds.[24][25] The bill's curvature specifically aids in maneuvering around buried prey's U-shaped burrows and withdrawing long, intact annelids without fragmentation, enhancing feeding efficiency in intertidal and prairie habitats.[25][26] Across the genus, bill length correlates with substrate type and prey depth, with longer bills in species favoring deep-probing in mud over surface pecking in drier grasslands.[27][23] Sexual dimorphism in size and bill morphology is prevalent, with females generally larger and possessing longer, more robust bills than males, a reversed pattern common in scolopacids that may reduce intraspecific competition for food resources or signal fitness during mate selection.[28][29] This dimorphism enables niche partitioning, as females target deeper or larger prey, while the overall streamlined body form, including pointed wings spanning up to 90 cm, supports endurance for long-distance migrations spanning continents.[4] The mottled plumage extends to downy chicks, which are precocial and rely on visual crypsis for predator avoidance in open nesting grounds.[22]Plumage, Size Variation, and Sexual Dimorphism

Curlews in the genus Numenius display cryptic plumage adapted for concealment in open habitats, characterized by mottled brownish upperparts with dark streaks and barring on a buff or cinnamon background, and paler, often white or streaked underparts.[30][31] This pattern persists year-round without marked seasonal variation in most species, though juveniles feature fresher, buff-tipped feathers for added camouflage.[32] Plumage lacks sexual dichromatism, with males and females indistinguishable by color or pattern.[33] Size varies substantially across the genus, reflecting ecological adaptations; for instance, the Far Eastern curlew (N. madagascariensis) measures 53–66 cm in length and weighs 565–1,150 g, while the Eurasian curlew (N. arquata) ranges 48–57 cm and 415–980 g.[34][35] Within species, body mass and dimensions fluctuate with age, condition, and geography; adult Long-billed curlews (N. americanus) span 50–65 cm and 490–950 g.[22] Bill length, a defining trait, scales with body size and can exceed 20 cm in larger species, enabling deep probing for prey.[7] Sexual dimorphism manifests chiefly in size, with females larger than males in body length, mass, and especially bill length—a pattern consistent across species to facilitate division of foraging niches during breeding.[22][36] In the Eurasian curlew, female bills average 13–15.2 cm versus 10–12.4 cm in males; similarly, Long-billed curlew females average 170 mm bills compared to 139 mm in males.[37][38] This size disparity aids sex determination via biometrics but does not extend to plumage differences.[39]| Species | Length (cm) | Wingspan (cm) | Weight (g) | Female Bill Length (cm) Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eurasian (N. arquata) | 48–57 | 89–106 | 415–980 | ~2–3 cm longer than males |

| Long-billed (N. americanus) | 50–65 | 62–89 | 490–950 | ~3 cm longer than males |

| Far Eastern (N. madagascariensis) | 53–66 | ~110 | 565–1,150 | Larger overall, specifics vary |

Distribution and Habitat

Breeding and Non-Breeding Ranges

Species of the genus Numenius breed predominantly in the temperate and Arctic zones of the Northern Hemisphere, with non-breeding ranges extending to subtropical and tropical regions across multiple continents. All eight recognized species follow this pattern of high-latitude nesting followed by southward migration.[40] The Eurasian curlew (N. arquata) breeds across a broad expanse from the British Isles through northwestern Europe, Scandinavia, and into Russia, extending eastward to Mongolia and northern China. Its non-breeding range encompasses coastal and wetland areas in western Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, southern Asia, and parts of the Middle East, with significant winter concentrations in the United Kingdom hosting approximately 30% of the western European population.[41][3] The whimbrel (N. phaeopus), one of the most widespread curlews, breeds in subarctic and Arctic tundra from Alaska across northern Canada, Greenland, and Eurasia to Siberia. Non-breeding grounds span from southern North America and the Caribbean southward to Bolivia in the Americas, and from Southeast Asia to Australia and southern Africa in the Old World, with migrations often involving transoceanic flights.[42][43] In North America, the long-billed curlew (N. americanus) nests in short- to mixed-grass prairies of the Great Plains, ranging from eastern New Mexico northward to the western Dakotas and southern Saskatchewan in Canada. It migrates to coastal estuaries, mudflats, and inland wetlands in California, the southwestern United States, and Mexico for the non-breeding period.[44][45] The Far Eastern curlew (N. madagascariensis) breeds in mossy bogs and wet meadows of northeastern Asia, including Siberia, Kamchatka Peninsula, and Mongolia. Its non-breeding range is concentrated in intertidal mudflats and coastal wetlands of Southeast Asia and Australia, where it undertakes one of the longest migrations among shorebirds.[46][47] Other species, such as the little curlew (N. minutus) in Russian taiga forests and the bristle-thighed curlew (N. tahitiensis) in western Alaska, similarly shift to Pacific island chains and Australasian wetlands during non-breeding seasons.[48][49]