Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Godwit

View on Wikipedia

| Godwit Temporal range: Barstovian–recent[1]

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-tailed (front) and bar-tailed godwit (back) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Limosa Brisson, 1760 |

| Type species | |

| Scolopax limosa Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

|

4, see text | |

Godwits are a group of four large, long-billed, long-legged and strongly migratory waders of the bird genus Limosa. Their long bills allow them to probe deeply in the sand for aquatic worms and molluscs. In their winter range, they flock together where food is plentiful. They frequent tidal shorelines, breeding in northern climates in summer and migrating south in winter. A female bar-tailed godwit made a flight of 29,000 km (18,000 mi), flying 11,680 kilometres (7,260 mi) of it without stopping.[2] In 2020 a male bar-tailed godwit flew about 12,200 kilometres (7,600 mi) non-stop in its migration from Alaska to New Zealand, previously a record for avian non-stop flight.[3] In October 2022, a 5 month old, male bar-tailed godwit was tracked from Alaska to Tasmania, a trip that took 11 days, and recorded a non-stop flight of 8,400 miles (13,500 km).[4]

The godwits can be distinguished from the curlews by their straight or slightly upturned bills, and from the dowitchers by their longer legs. The winter plumages are fairly drab, but three species have reddish underparts when breeding. The females are appreciably larger than the males.

Godwits were once popular as food in the British Isles. Sir Thomas Browne writing in about 1682 noted that godwits "were accounted the daintiest dish in England".[5]

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus Limosa was introduced by the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson in 1760 with the black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) as the type species.[6][7] The genus name Limosa is from Latin and means "muddy", from limus, "mud".[8] The English name "godwit" was first recorded in about 1416–17 and is believed to imitate the bird's call.[5]

The genus contains four living species:[9]

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bar-tailed godwit | Limosa lapponica (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Scandinavia to Alaska, temperate and tropical regions of Australia and New Zealand. | Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT

|

| Black-tailed godwit | Limosa limosa (Linnaeus, 1758) |

the Indian subcontinent, Australia, New Zealand, western Europe and west Africa.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

NT

|

| Hudsonian godwit | Limosa haemastica (Linnaeus, 1758) |

northern Canada and winters in southern South America.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

VU

|

| Marbled godwit | Limosa fedoa (Linnaeus, 1758) Two subspecies

|

Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts of the US and Mexico.

|

Size: Habitat: Diet: |

VU

|

Fossil species

[edit]In addition, there are two or three species of fossil prehistoric godwits. Limosa vanrossemi is known from the Monterey Formation (Late Miocene, approx. 6 mya) of Lompoc, United States. Limosa lacrimosa is known from the Early Pliocene of Western Mongolia (Kurochkin, 1985). Limosa gypsorum of the Late Eocene (Montmartre Formation, some 35 mya) of France may have actually been a curlew or some bird ancestral to both curlews and godwits (and possibly other Scolopacidae), or even a rail, being placed in the monotypic genus Montirallus by some (Olson, 1985). Certainly, curlews and godwits are rather ancient and in some respects primitive lineages of scolopacids, further complicating the assignment of such possibly basal forms.[10]

In a 2001 study comparing the ratios cerebrum to brain volumes in various dinosaur species, Hans C. E. Larsson found that more derived dinosaurs generally had proportionally more voluminous cerebrum.[11] Limosa gypsorum, then regarded as a Numenius species, was a discrepancy in this general trend.[12] L. gypsorum was only 63% of the way between a typical reptilian ratio and that of modern birds.[12] However, this may be explainable if the endocast was distorted, as it had been previously depicted in the past by Deschaseaux, who is described by Larsson as calling the endocast "slightly anteroposteriorly sheared and laterally compressed."[12]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Limosa Brisson 1760 (godwit)". PBDB.

- ^ "Bird Completes Epic Flight Across the Pacific". ScienceDaily. US Geological Survey. 17 September 2007.

- ^ Boffey, Daniel (13 October 2020). "'Jet fighter' godwit breaks world record for non-stop bird flight". The Guardian.

- ^ "An Incredible Bird Was Tracked As It Made A Cross-Globe Journey From Alaska To Tasmania (video)". The Weather Channel. 27 October 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Godwit". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode Contenant la Divisio Oiseaux en Ordres, Sections, Genres, Especes & leurs Variétés (in French and Latin). Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. Vol. 1, p. 48, Vol. 5, p. 261.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 263.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "Buttonquail, plovers, seedsnipe, sandpipers". World Bird List Version 9.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Gavin H.; Wills, Matthew A.; Székely, Tamás (2004). "A supertree approach to shorebird phylogeny". BMC Evol. Biol. 4: 28. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-28. PMC 515296. PMID 15329156.

- ^ "Allometric Comparison", in Larsson (2001). p. 27.

- ^ a b c "Allometric Comparison", in Larsson (2001). p. 30.

General sources

[edit]- Gill, R. E. Jr.; Piersma, T.; Hufford, G.; Servranckx, R.; Riegen, A. (2005). "Crossing the ultimate ecological barrier: evidence for an 11,000-km-long non-stop flight from Alaska to New Zealand and Eastern Australia by Bar-tailed Godwits". Condor. 107: 1–20. doi:10.1650/7613. hdl:11370/531c931d-e4bd-427c-a6ad-1496c81d44c0.

- Larsson, H. C. E. 2001. Endocranial anatomy of Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) and its implications for theropod brain evolution. pp. 19–33. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. (eds.). Indiana University Press.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985): Section X.D.2.b. "Scolopacidae". In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 174–175. Academic Press, New York.

Godwit

View on GrokipediaPhysical characteristics

Plumage and morphology

Godwits possess a long, slightly upcurved bill measuring 7–12 cm in length depending on the species, which is adapted for probing soft mud and sediment in search of invertebrate prey.[10][11] The bill's structure allows for deep insertion into substrates, with the upturned tip facilitating detection of buried items through tactile sensitivity in the bill tip.[12] Their legs are long and suited for wading in shallow water, while the feet feature three forward-pointing toes and a short hind toe, providing stability on soft terrain typical of wetland environments.[13][14] This anisodactyl foot arrangement is characteristic of shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, enabling efficient locomotion across mudflats.[14] Plumage in godwits exhibits seasonal variation, with breeding adults displaying vibrant patterns for courtship and camouflage in tundra habitats. For instance, breeding Bar-tailed Godwits (Limosa lapponica) feature brick-red underparts, while Black-tailed Godwits (Limosa limosa) show black-and-white patterns with rufous tones on the head and breast.[13][12] In contrast, non-breeding adults across species adopt duller gray-brown upperparts and paler underparts, aiding crypsis in coastal foraging areas.[10][15] Wings are pointed and adapted for efficient long-distance flight, with structural features like a narrow white wing stripe in species such as the Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) visible during migration.[15] Godwits undergo a complete post-breeding molt of flight feathers on non-breeding grounds, typically from late summer to early winter, replacing primaries and secondaries to prepare for return journeys.[16][17] Bill coloration shifts seasonally, appearing darker overall in the breeding period due to intensified pigmentation at the base, while non-breeding bills are paler with pinkish or orange tones.[18][10] This change correlates with hormonal influences during reproduction.[18]Size and sexual dimorphism

Godwits exhibit moderate size variation across the four species in the genus Limosa, with overall body lengths typically ranging from 36 to 50 cm, wingspans of 70 to 88 cm, and body masses between 200 and 520 g.[19][20][15] The Hudsonian Godwit (L. haemastica) represents the smallest species, averaging 36–42 cm in length and 196–358 g in weight, while the Marbled Godwit (L. fedoa) is the largest at 42–50 cm long and 240–520 g.[15][20] The Black-tailed Godwit (L. limosa) measures 36–44 cm with a wingspan of 70–82 cm and weighs 160–500 g, and the Bar-tailed Godwit (L. lapponica) is 37–45 cm long with a similar wingspan of 70–80 cm and masses of 190–630 g, though typical non-migratory weights fall in the 250–450 g range.[19][13] Sexual dimorphism is pronounced in godwits, with females consistently larger than males across all species—a pattern known as reverse sexual size dimorphism common in scolopacid shorebirds.[21] Females exceed males by 10–20% in key linear dimensions such as bill length, wing length, and tarsus length, with bill dimorphism often reaching 20–22% in species like the Hudsonian and Marbled godwits.[22][23] For instance, in the Black-tailed Godwit, female bill length averages 10–15% longer than males, while in the Hudsonian Godwit, female culmen measures 88–90 mm compared to 73–76 mm in males.[24][22] This size disparity aids niche partitioning during the breeding season, as larger female bills allow access to deeper invertebrate prey in wetland sediments, reducing intraspecific competition with smaller males.[21][25] Juveniles are smaller than adults at fledging, reflecting incomplete skeletal and feather development.[26] Growth rates are sex-specific, with female chicks exhibiting faster mass gain and morphometric expansion to achieve adult proportions by the first migration, though overall maturation can extend into the second year.[27] In the Black-tailed Godwit, for example, juvenile body mass averages 282 g compared to 299 g in adults, with slower initial growth in males contributing to persistent dimorphism.[26] Intraspecific variation further influences size, particularly in polytypic species like the Bar-tailed Godwit, where subspecies differ due to geographic and environmental factors. Alaskan-breeding birds (L. l. baueri) are among the largest forms, averaging up to 50 g heavier than smaller Asian or European subspecies such as L. l. menzbieri, with differences most evident in wing and body mass.[1] Similarly, in the Black-tailed Godwit, the nominate L. l. limosa subspecies is 5–10% larger in tarsus and wing than the smaller L. l. melanuroides.[24] These variations likely reflect adaptations to local breeding conditions and migratory demands.Distribution and habitat

Breeding and wintering ranges

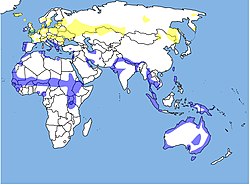

Godwits, belonging to the genus Limosa, exhibit distinct breeding ranges primarily in northern high-latitude wetlands and tundra regions, where they nest during the boreal summer. The Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica) breeds across the Eurasian Arctic from northern Scandinavia discontinuously eastward to the Russian Far East, including western Alaska.[8] The Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) occupies boreal and subarctic wet sedge meadows and tundra across the North American Arctic, from Alaska to the southern edge of Hudson Bay in Canada.[28][7] In contrast, the Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) breeds mainly in the northern Great Plains' prairie pothole region, spanning southern Canada and the northern United States, with smaller isolated populations on tundra near James Bay, Ontario, and in Alaska. However, recent monitoring as of 2024 indicates rapid declines, leading to an uplisting to Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List, with potential contractions in wintering concentrations along the Pacific coast.[29][30] The Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa) has a broad discontinuous breeding distribution from Iceland across Europe to central Asia and the Russian Far East, favoring fens, damp meadows, and bogs.[9] During the non-breeding season, godwits migrate to temperate and tropical coastal zones, where they exploit intertidal mudflats and estuaries rich in invertebrate prey. The Bar-tailed Godwit winters along the coasts of southeast Asia, Australia, and New Zealand, with some populations utilizing Atlantic shores in Europe and Africa.[8][31] The Black-tailed Godwit overwinters in diverse locales including western Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Australasia, particularly Australia for the subspecies L. l. melanuroides.[9] The Hudsonian Godwit concentrates in southern South America, primarily along the coasts of Argentina and Chile, with smaller numbers in Brazil and Peru.[7][32] The Marbled Godwit winters coastally in North and Central America, with key concentrations from central California southward through Mexico to the Gulf of California and Salton Sea regions.[29][3] Certain wintering areas serve as overlap zones for multiple godwit species, facilitating shared use of productive estuarine habitats. In New Zealand and eastern Australia, Bar-tailed and Black-tailed Godwits co-occur on mudflats and tidal zones during the austral summer, though Black-tailed individuals are less numerous and primarily of the Asian subspecies.[9][33] Historical shifts in godwit ranges reflect responses to habitat alteration and conservation efforts. The Marbled Godwit underwent dramatic declines in the early 1900s due to overhunting and prairie conversion, leading to extirpation from former breeding sites in the U.S. Midwest, but its range has since expanded in prairie Canada, including extensions into southeastern Alberta by the mid-20th century.[34][3][35]Preferred environments

Godwits, belonging to the genus Limosa, exhibit distinct habitat preferences that vary between breeding and non-breeding seasons, reflecting their adaptations as long-distance migratory shorebirds. During the breeding season, species such as the bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica) and Hudsonian godwit (Limosa haemastica) favor moist tundra meadows and river deltas characterized by sedges, mosses, and shallow water bodies.[8][36] These environments provide the necessary conditions for nesting in simple scrapes lined with lichens and mosses, often concealed among tussocks and dwarf shrubs, while supporting high insect abundance essential for chick rearing.[4][37] The marbled godwit (Limosa fedoa), in contrast, breeds in shortgrass prairies adjacent to wetlands, preferring sparsely vegetated uplands with native grasses and proximity to shallow ponds or marshes for similar ecological benefits.[3][38] In the non-breeding season, godwits shift to coastal and estuarine habitats, predominantly intertidal mudflats, saltmarshes, and mangrove edges featuring soft, probeable substrates.[4][39] These areas, utilized by species like the black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) and bar-tailed godwit, offer expansive tidal flats with fine sediments ideal for accessing benthic invertebrates, often extending into brackish lagoons or edges of mangrove systems in subtropical regions.[40] The Hudsonian godwit similarly occupies mudflats and saltmarshes in South American estuaries, while the marbled godwit frequents similar soft-bottomed coastal wetlands along the Pacific and Gulf coasts.[41][30] Godwits display specific microhabitat preferences that enhance foraging efficiency and predator avoidance, including salinity gradients from brackish to hypersaline conditions tolerated via specialized salt glands, and low vegetation cover to maintain visibility across open flats.[42] In breeding areas, they select tussocky sedge-moss mosaics with minimal shrub density, whereas non-breeding sites emphasize bare or sparsely vegetated mud and sand for unobstructed movement.[43][3] These preferences underscore godwits' reliance on dynamic wetland cycles, such as tidal fluctuations in coastal habitats, to access resources, with non-breeding and stopover sites in regions like the Yellow Sea exhibiting vulnerability to hydrological variations including seasonal droughts that alter wetland availability.[44][45]Behavior and ecology

Feeding habits

Godwits primarily consume invertebrates, including polychaete worms, crustaceans, mollusks such as clams, and insects, which form the bulk of their diet across species. During the breeding season, they incorporate more high-protein items like insects and spiders, along with plant matter such as berries, seeds, and roots to supplement their intake in tundra or grassland habitats. In contrast, wintering godwits shift toward marine prey, emphasizing mollusks like clams (Darina solenoides) and polychaetes (Scolecolepides uncinatus), which provide abundant energy in coastal intertidal zones.[46][47][48] Foraging techniques rely on the species' long, sensitive bills, which allow tactile detection of buried prey through probing into mud or soft sediments, often at rates of 15–60 probes per minute depending on habitat and prey density. Godwits may also sweep their bills side-to-side to stir up hidden invertebrates or visually peck at exposed items on the surface, particularly in drier or vegetated areas. These methods enable efficient exploitation of intertidal flats, where the slightly upturned bill morphology facilitates deep penetration without resistance.[49][50][51] Daily feeding routines involve consuming 50–100 grams of food, equivalent to roughly 20–22 grams of ash-free dry weight, to meet energetic demands, with intake rates varying from 0.7–7 items per minute based on prey availability and foraging efficiency. Peak activity occurs during low tides in coastal environments, when expansive mudflats are exposed, allowing extended bouts of probing; in inland or upland sites, godwits forage throughout daylight hours to gather dispersed resources. This tidal synchronization maximizes access to high-density prey patches, supporting maintenance metabolism and seasonal needs.[46][52][49]Migration and navigation

Godwits undertake some of the longest non-stop migrations among birds, with the bar-tailed godwit (Limosa lapponica) holding records for epic trans-Pacific journeys. Individuals of the Alaskan subspecies (L. l. baueri) regularly fly approximately 11,000 km from breeding grounds in western Alaska to non-breeding sites in New Zealand, completing the flight in 8–9 days without landing for food or rest. One tracked individual covered over 13,500 km from Alaska to Tasmania in 11 days, the longest continuous flight recorded for a landbird.[53] The black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) follows similar patterns along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, migrating between Eurasian breeding areas and Australasian wintering grounds, though with more frequent stopovers.[54] In the Americas, the Hudsonian godwit (Limosa haemastica) migrates along routes spanning the Western Hemisphere, breeding in subarctic Canada and Alaska before flying non-stop over the Atlantic from James Bay to northern South America, covering up to 6,000 km in a single leg.[55] Further south, it continues to wintering areas in Tierra del Fuego, with total annual distances exceeding 25,000 km. The marbled godwit (Limosa fedoa) has shorter migrations, primarily through the interior of North America and along Pacific coasts, from prairie breeding sites to coastal wintering areas in Mexico and Central America, typically involving multiple stops and distances of 2,000–4,000 km per leg.[56] Godwits navigate these vast distances using a combination of celestial, geomagnetic, and other sensory cues, integrating multiple inputs for orientation over open ocean and unfamiliar terrain. Celestial navigation relies on the sun's position during the day and stars at night, calibrated by an internal clock to maintain direction.[57] Geomagnetic fields provide a compass-like sense of direction and position, with birds detecting Earth's magnetic inclination and intensity to extrapolate location beyond familiar ranges.[58] Physiological preparations enable these endurance feats, with godwits accumulating substantial fat reserves—up to 55% of body mass in bar-tailed godwits prior to departure—to fuel prolonged flight without feeding.[59] This hyperphagia phase involves rapid lipid deposition, often tripling body mass in weeks, supported by enlarged digestive organs that later atrophy to reduce weight. Flight muscles, including the pectoralis and supracoracoideus, undergo adaptations such as increased lean mass and oxidative capacity for efficient aerobic metabolism, while the heart enlarges to enhance oxygen delivery during sustained exertion.[60] These changes, reversible post-migration, optimize energy use and minimize drag for non-stop travel.Breeding and reproduction

Godwits typically form monogamous pairs for a single breeding season, with some pairs reuniting in subsequent years, as observed in species such as the Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) and Marbled Godwit (L. fedoa).[41][3] Courtship involves elaborate aerial displays by males, including spiraling flights, slow wingbeats, and vocalizations to attract females and establish territories, though breeding often occurs in loose semi-colonial groups rather than strict leks.[41][9] Unmated males may attempt extra-pair copulations with established pairs, contributing to occasional polygyny.[41] Nesting sites are simple ground scrapes, typically 12-15 cm in diameter and 4-5 cm deep, concealed in short vegetation such as sedges, grasses, or tussocks in wetland or prairie habitats.[4][9] Both sexes collaborate to create and line the scrape with moss, lichens, leaves, root fibers, or grasses, often selecting dry hummocks or areas near shrubs for camouflage.[4][41] Clutch sizes generally consist of 4 eggs (ranging from 2-5 across species), which are olive, buff, or greenish with dark spots or scrawls for cryptic coloration; laying occurs synchronously, with one egg per day.[4][9][3] Incubation, lasting 20-26 days depending on the species, is shared by both parents—females often during the day and males at night—with the eggs hatching asynchronously over 1-2 days.[4][3][61] Godwit chicks are precocial, hatching covered in down with open eyes and the ability to run, swim, and forage within hours of emergence, though they remain dependent on parental care.[4][3] Both parents brood and feed the brood insects and invertebrates for 28-42 days until fledging, during which time the family may move to secondary habitats like tidal marshes; adults often depart migration sites before juveniles achieve independence.[4][62][9] Pairs aggressively defend nests and chicks against predators, including foxes and gulls, up to 0.5 km from the site.[4] Reproductive success varies by species, location, and environmental factors, with hatching rates often reaching 50-70% in protected areas, but overall fledging success is low at 0.2-1 fledgling per pair due to high predation and habitat pressures.[63][64] Populations require at least 0.6 fledglings per pair annually for stability, a threshold rarely met without management interventions like predator control.[65][66]Taxonomy and systematics

Species classification

The godwits are classified in the genus Limosa within the family Scolopacidae, comprising four extant species: the Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica), Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica), and Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa). These long-legged, long-billed shorebirds are distinguished primarily by plumage patterns and tail characteristics; for instance, the Bar-tailed Godwit lacks a white rump and exhibits a cinnamon-barred tail in flight, contrasting with the Black-tailed Godwit's prominent white rump and black tail, while the Hudsonian Godwit displays bolder underwing barring and a white-based, black-tipped tail compared to the more uniformly dark underwing of the Marbled Godwit.[67][68][69] The genus includes a total of twelve recognized subspecies, reflecting geographic variation across breeding ranges; examples include L. lapponica baueri (the Pacific subspecies of the Bar-tailed Godwit, breeding in Alaska and eastern Siberia) and the four subspecies of the Black-tailed Godwit (L. l. islandica, L. l. limosa, L. l. melanuroides, and L. l. bohaii). The Marbled Godwit has two subspecies (L. f. fedoa and L. f. beringiae), while the Hudsonian Godwit is monotypic. Genetic studies indicate minimal divergence among the traditionally recognized Black-tailed Godwit subspecies based on mitochondrial DNA, with haplotype networks showing shallow separation, though some populations exhibit distinct morphological and genetic markers suggestive of recent isolation. For Bar-tailed Godwit subspecies, genomic analyses reveal post-glacial diversification, with lineages splitting as recently as 4,500–38,200 years ago, driven by high dispersal and migratory traditions rather than deep genetic barriers.[70][9][71][72][73][74] Phylogenetically, the genus Limosa is part of the tribe Limosini in the subfamily Scolopacinae, with curlews of the genus Numenius identified as the closest relatives based on both molecular (cytochrome b) and morphological data. Within Limosa, species relationships show L. lapponica diverging first, followed by a rapid radiation of the remaining three species approximately 6–8 million years ago during the late Miocene, consistent with fossil evidence of the genus originating 15–25 million years ago.[1][75][6]Evolutionary history

The genus Limosa, comprising the godwits, has a fossil record extending to the late Eocene, with the earliest known species, Limosa gypsorum, discovered in the Montmartre Formation of France and dated to approximately 35 million years ago. This fossil suggests an early divergence within the Scolopacidae family, potentially representing a common ancestor to godwits and curlews (Numenius spp.), as its morphology exhibits intermediate bill characteristics between the straight bills of modern godwits and the decurved bills of curlews.[76] The lineage likely originated in Eurasia during the Miocene around 20 million years ago, with subsequent spread to North America, marking the divergence from curlew ancestors as shorebird clades diversified in response to expanding wetland habitats.[6] Phylogenetic analyses indicate that the core Limosa radiation occurred later, with molecular clock estimates from cytochrome b sequences placing the split among extant species (L. lapponica, L. limosa, L. haemastica, and L. fedoa) at 6–8 million years ago during the late Miocene to early Pliocene.[75] Fossil evidence from the Miocene and Pliocene further documents the genus's expansion across continents. Limosa vanrossemi, from the Late Miocene Monterey Formation in California (approximately 6 million years ago), represents one of the earliest North American records and shows morphological similarities to the modern marbled godwit (L. fedoa).[76] In the Early Pliocene, Limosa lacrimosa from deposits in western Mongolia (around 5 million years ago) indicates the genus's presence in Asian wetlands, highlighting its adaptation to diverse northern hemisphere environments during a period of climatic cooling and habitat fragmentation.[76] These fossils underscore a pattern of intercontinental dispersal, likely facilitated by land bridges and migratory behaviors evolving in the family Scolopacidae. Key adaptive traits, particularly the evolution of the long, straight bill, enabled godwits to exploit deep-probing niches in soft sediments for invertebrates, distinguishing them from curlews' surface-foraging strategy and driving an adaptive radiation within shorebirds. Beak elongation emerged as a key innovation in the Miocene, allowing access to buried prey in mudflats and tundra, which promoted diversification into coastal and Arctic ecosystems. Post-Pleistocene glaciations further shaped this radiation, as retreating ice sheets opened breeding grounds and prompted recolonization from unglaciated refugia, leading to the current circumpolar distribution. Genetic evidence from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) supports Beringia as a major diversification center for godwits around 3 million years ago, coinciding with Pliocene-Pleistocene climatic shifts that isolated populations and fostered speciation in Arctic shorebirds. Phylogeographic studies of the bar-tailed godwit (L. lapponica) reveal pre-Last Glacial Maximum lineage structure in Beringia, with subsequent post-glacial admixture and westward expansion into Europe, confirming the region's role in recent evolutionary history.Conservation status

Population trends

The global populations of godwit species vary significantly among the four recognized species, with estimates derived from comprehensive waterbird censuses and breeding bird surveys. The Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica) has an estimated 770,000–880,000 mature individuals, primarily comprising the subspecies taymyrensis (625,000) and lapponica (150,000–180,000). Recent 2025 genetic and ringing studies indicate potential mixing of Bar-tailed Godwit subspecies in European wintering sites, suggesting a need to revisit population estimates and trends.[77] The Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa) numbers 672,000–873,000 individuals across six flyway populations.[9] In contrast, the Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemastica) supports a much smaller population of 41,000–70,000 mature individuals, while the Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa) is estimated at 270,000 mature individuals.[7][29] These figures, based on 2023–2025 surveys, highlight the relative abundance of Old World species compared to their New World counterparts.[78] Population trends indicate ongoing declines for most godwit species, though the magnitude varies by region and subspecies. The Bar-tailed Godwit has experienced a global decrease of 15–29% over the past three generations (approximately 24 years), with sharper reductions in certain flyways, such as a 23% decline in the Alaskan subspecies from 1995–2012.[8] Similarly, the Black-tailed Godwit shows a 20–29% reduction over three generations, affecting multiple European and Asian populations.[9] The Hudsonian Godwit is decreasing at a rate of 20–37% over the same period, with limited recovery observed in core breeding areas.[7] For the Marbled Godwit, breeding populations have declined by about 17% from 1994–2021, alongside a 7.7% annual drop in wintering numbers in key Mexican and Californian sites from 2011–2019.[29] Regional variations exist; for instance, some Alaskan Marbled Godwit populations exhibit stability or slight increases of around 3% annually in localized surveys, contrasting broader continental trends.[79] Monitoring godwit populations relies on a combination of standardized methods to track changes across breeding, migration, and wintering sites. Aerial and ground-based surveys, such as the North American Breeding Bird Survey and International Waterbird Census, provide annual indices of abundance.[78] Satellite tagging and color-banding programs, coordinated by organizations like Wetlands International and BirdLife International, enable individual tracking and estimation of survival rates, with data integrated into flyway-scale assessments.[8][7] These efforts, including stopover site counts during migration, have improved precision in detecting trends since the early 2000s.[80]| Species | Global Estimate (Mature Individuals) | Trend (Over ~3 Generations) | Key Monitoring Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bar-tailed Godwit | 770,000–880,000 | Decreasing (15–29%) | Wetlands International (2024); BirdLife (2025) |

| Black-tailed Godwit | 672,000–873,000 | Decreasing (20–29%) | Wetlands International (2025); BirdLife (2025) |

| Hudsonian Godwit | 41,000–70,000 | Decreasing (20–37%) | BirdLife (2024); Smith et al. (2023) |

| Marbled Godwit | 270,000 | Decreasing (~17% breeding) | Partners in Flight (2023); Muñoz-Salas et al. (2023) |