Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cusk-eel

View on Wikipedia

| Cusk-eel Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

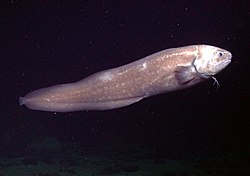

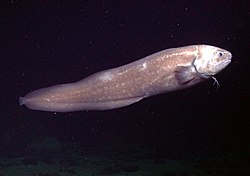

| Pudgy cusk-eel (Spectrunculus grandis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Ophidiiformes |

| Suborder: | Ophidioidei |

| Family: | Ophidiidae Rafinesque, 1810 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

See text | |

The cusk-eel family, Ophidiidae, is a group of marine bony fishes in the Ophidiiformes order. The scientific name is from the Greek ophis meaning "snake", and refers to their eel-like appearance. True eels diverged from other ray-finned fish during the Jurassic, while cusk-eels are part of the Percomorpha clade, along with tuna, perch, seahorses, and others.

The oldest fossil cusk-eel is Ampheristus, a highly successful genus with numerous species that existed from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) to the early Oligocene.[1][2]

Distribution

[edit]Cusk-eels live in temperate and tropical oceans throughout the world. They live close to the sea bottom, ranging from shallow water to the hadal zone. One species, Abyssobrotula galatheae, was recorded at the bottom of the Puerto Rico Trench, making it the deepest recorded fish at 8,370 m (27,460 ft).[3][4]

Ecology

[edit]Cusk-eels are generally very solitary in nature, but some species have been seen to associate themselves with tube worm communities.[5] Liking to be hidden when they are not foraging, they generally associate themselves within muddy bottoms, sinkholes, or larger structures that they can hide in or around, such as caves, coral crevices, or communities of bottom-dwelling invertebrates, with some parasitic species of cusk-eel actually living inside of invertebrate hosts, such as oysters, clams and sea cucumbers.[5] Cusk-eels generally feed nocturnally, preying on invertebrates, crustaceans and other small bottom-dwelling fishes.

Phylogeny

[edit]Due to the inconsistencies in specific morphological characteristics in closely related species, attempts to use different characteristics, such as the position of pelvic fins, to classify Ophiididae into distinct families have proven highly unsatisfactory. Overall, Ophidiidae are classified based on whether or not they practice viviparity and the structures they contain that are associated with bearing life.[5]

Characteristics

[edit]Cusk-eels are characterized by a long, slender body that is about 12–13 times as long as it is deep. The largest species, Lamprogrammus shcherbachevi, grows up to 2 m (6.6 ft) in length[citation needed], but most species are shorter than 1 m (3.3 ft). Their dorsal and anal fins are typically continuous with the caudal fin (with exception to a few species), forming a long, ribbon like fin around the posterior of the cusk-eel's body.[6] This caudal fin will often be seen to be reduced to a fleshy or bony point, especially when confluent with the dorsal and anal fins. The dorsal fin to anal fin ray ratio is approximately 1.5:1, leading to the dorsal fin typically being longer than the anal. The pectoral fins of cusk-eels are typically longer than the length of their head. Unlike true eels of the order Anguilliformes, cusk-eels have ventral fins that are developed into a forked barbel-like organ below the mouth. In true eels by contrast, the ventral fins are never well-developed and usually missing entirely.[7] Cusk-eels have large mouths relative to their heads, with the upper jaw reaching beyond the eye, and paired nostrils on either side of the head. In cusk-eels, scales are potentially absent; when present, they are small.[6]

Reproduction

[edit]Unlike their close relatives, the viviparous brotulas of the family Bythitidae, cusk-eel species are egg-bearing, or oviparous, organisms. While the specifics of the eggs of the family Ophidiidae are unknown, they are believed to be either spawned as individual, free-floating eggs in the open water or are placed in a mucilaginous raft, which will float for several days until they hatch into cusk-eel larvae. These larvae live amongst the plankton relatively close to the water's surface[3] and are believed to control their metamorphoses into adult cusk-eels, dispersing over greater distances into less utilized habitats and reducing competition in concentrated areas.[5]

Conservation status

[edit]While a few species are fished commercially – most notably the pink cusk-eel, Genypterus blacodes – and several species of the order Ophidiiformes are listed as vulnerable, not enough information has been gathered about Ophidiidae as a whole to determine their conservation status.

Genera

[edit]The cusk-eel family contains about 240 species, grouped into 50 genera:[8]

- Genus †Ampheristus[2]

Subfamily Brotulotaenilinae

- Genus Brotulotaenia

Subfamily Neobythitinae

- Genus Abyssobrotula

- Genus Alcockia

- Genus Apagesoma

- Genus Barathrites

- Genus Barathrodemus

- Genus Bassogigas

- Genus Bassozetus

- Genus Bathyonus

- Genus Benthocometes

- Genus Dannevigia – Australian tusk

- Genus Dicrolene

- Genus Enchelybrotula

- Genus Epetriodus – needletooth cusk

- Genus Eretmichthys

- Genus Glyptophidium

- Genus Holcomycteronus

- Genus Homostolus – filament cusk

- Genus Hoplobrotula

- Genus Hypopleuron – whiptail cusk

- Genus Lamprogrammus

- Genus Leptobrotula

- Genus Leucicorus

- Genus Luciobrotula

- Genus Mastigopterus

- Genus Monomitopus

- Genus Neobythites

- Genus Neobythitoides

- Genus Penopus

- Genus Petrotyx

- Genus Porogadus

- Genus Pycnocraspedum

- Genus Selachophidium – Gunther's cusk-eel

- Genus Sirembo

- Genus Spectrunculus

- Genus Spottobrotula

- Genus Tauredophidium

- Genus Tenuicephalus

- Genus Typhlonus

- Genus Ventichthys – East-Pacific ventbrotula

- Genus Xyelacyba

Subfamily Ophidiinae

- Genus Cherublemma – black brotula

- Genus Chilara – spotted cusk-eel

- Genus Genypterus

- Genus Lepophidium

- Genus Menziesichthys

- Genus Ophidion

- Genus Otophidium

- Genus Parophidion

- Genus Raneya – banded cusk-eel

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Schwarzhans, Werner; Stringer, Gary L. (2020-05-06). "Fish Otoliths from the Late Maastrichtian Kemp Clay (Texas, Usa) and the Early Danian Clayton Formation (Arkansas, Usa) and an Assessment of Extinction and Survival of Teleost Lineages Across the K-Pg Boundary Based on Otoliths". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia. 126 (2). doi:10.13130/2039-4942/13425. ISSN 2039-4942.

- ^ a b "PBDB". paleobiodb.org. Retrieved 2024-02-16.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Jørgen G. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 134. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ^ "What is the deepest-living fish?". Australian Museum. 23 December 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Ophidiiformes (Cusk-Eels and Relatives) | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ^ a b Bigelow, Andrew (2002). Bigelow and Schroeder's fishes of the Gulf of Maine. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Ophidiidae". FishBase. February 2006 version.

- ^ Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W. N.; Van der Laan, R. (2025). "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: CLASSIFICATION". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2025-02-10.