Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

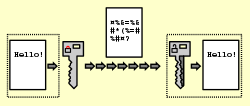

Encryption

View on Wikipedia

In cryptography, encryption (more specifically, encoding) is the process of transforming information in a way that, ideally, only authorized parties can decode. This process converts the original representation of the information, known as plaintext, into an alternative form known as ciphertext. Despite its goal, encryption does not itself prevent interference but denies the intelligible content to a would-be interceptor.

For technical reasons, an encryption scheme usually uses a pseudo-random encryption key generated by an algorithm. It is possible to decrypt the message without possessing the key but, for a well-designed encryption scheme, considerable computational resources and skills are required. An authorized recipient can easily decrypt the message with the key provided by the originator to recipients but not to unauthorized users.

Historically, various forms of encryption have been used to aid in cryptography. Early encryption techniques were often used in military messaging. Since then, new techniques have emerged and become commonplace in all areas of modern computing.[1] Modern encryption schemes use the concepts of public-key[2] and symmetric-key.[1] Modern encryption techniques ensure security because modern computers are inefficient at cracking the encryption.

History

[edit]Ancient

[edit]One of the earliest forms of encryption is symbol replacement, which was first found in the tomb of Khnumhotep II, who lived in 1900 BC Egypt. Symbol replacement encryption is “non-standard,” which means that the symbols require a cipher or key to understand. This type of early encryption was used throughout Ancient Greece and Rome for military purposes.[3] One of the most famous military encryption developments was the Caesar cipher, in which a plaintext letter is shifted a fixed number of positions along the alphabet to get the encoded letter. A message encoded with this type of encryption could be decoded with a fixed number on the Caesar cipher.[4]

Around 800 AD, Arab mathematician al-Kindi developed the technique of frequency analysis – which was an attempt to crack ciphers systematically, including the Caesar cipher.[3] This technique looked at the frequency of letters in the encrypted message to determine the appropriate shift: for example, the most common letter in English text is E and is therefore likely to be represented by the letter that appears most commonly in the ciphertext. This technique was rendered ineffective by the polyalphabetic cipher, described by al-Qalqashandi (1355–1418)[2] and Leon Battista Alberti (in 1465), which varied the substitution alphabet as encryption proceeded in order to confound such analysis.

19th–20th century

[edit]Around 1790, Thomas Jefferson theorized a cipher to encode and decode messages to provide a more secure way of military correspondence. The cipher, known today as the Wheel Cipher or the Jefferson Disk, although never actually built, was theorized as a spool that could jumble an English message up to 36 characters. The message could be decrypted by plugging in the jumbled message to a receiver with an identical cipher.[5]

A similar device to the Jefferson Disk, the M-94, was developed in 1917 independently by US Army Major Joseph Mauborne. This device was used in U.S. military communications until 1942.[6]

In World War II, the Axis powers used a more advanced version of the M-94 called the Enigma Machine. The Enigma Machine was more complex because unlike the Jefferson Wheel and the M-94, each day the jumble of letters switched to a completely new combination. Each day's combination was only known by the Axis, so many thought the only way to break the code would be to try over 17,000 combinations within 24 hours.[7] The Allies used computing power to severely limit the number of reasonable combinations they needed to check every day, leading to the breaking of the Enigma Machine.

Modern

[edit]Today, encryption is used in the transfer of communication over the Internet for security and commerce.[1] As computing power continues to increase, computer encryption is constantly evolving to prevent eavesdropping attacks.[8] One of the first "modern" cipher suites, DES, used a 56-bit key with 72,057,594,037,927,936 possibilities; it was cracked in 1999 by EFF's brute-force DES cracker, which required 22 hours and 15 minutes to do so. Modern encryption standards often use stronger key sizes, such as AES (256-bit mode), TwoFish, ChaCha20-Poly1305, Serpent (configurable up to 512-bit). Cipher suites that use a 128-bit or higher key, like AES, will not be able to be brute-forced because the total amount of keys is 3.4028237e+38 possibilities. The most likely option for cracking ciphers with high key size is to find vulnerabilities in the cipher itself, like inherent biases and backdoors or by exploiting physical side effects through Side-channel attacks. For example, RC4, a stream cipher, was cracked due to inherent biases and vulnerabilities in the cipher.

Encryption in cryptography

[edit]In the context of cryptography, encryption serves as a mechanism to ensure confidentiality.[1] Since data may be visible on the Internet, sensitive information such as passwords and personal communication may be exposed to potential interceptors.[1] The process of encrypting and decrypting messages involves keys. The two main types of keys in cryptographic systems are symmetric-key and public-key (also known as asymmetric-key).[9][10]

Many complex cryptographic algorithms often use simple modular arithmetic in their implementations.[11]

Types

[edit]In symmetric-key schemes,[12] the encryption and decryption keys are the same. Communicating parties must have the same key in order to achieve secure communication. The German Enigma Machine used a new symmetric-key each day for encoding and decoding messages.

In public-key cryptography schemes, the encryption key is published for anyone to use and encrypt messages. However, only the receiving party has access to the decryption key that enables messages to be read.[13] Public-key encryption was first described in a secret document in 1973;[14] beforehand, all encryption schemes were symmetric-key (also called private-key).[15]: 478 Although published subsequently, the work of Diffie and Hellman was published in a journal with a large readership, and the value of the methodology was explicitly described.[16] The method became known as the Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is another notable public-key cryptosystem. Created in 1978, it is still used today for applications involving digital signatures.[17] Using number theory, the RSA algorithm selects two prime numbers, which help generate both the encryption and decryption keys.[18]

A publicly available public-key encryption application called Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) was written in 1991 by Phil Zimmermann, and distributed free of charge with source code. PGP was purchased by Symantec in 2010 and is regularly updated.[19]

Uses

[edit]Encryption has long been used by militaries and governments to facilitate secret communication. It is now commonly used in protecting information within many kinds of civilian systems. For example, the Computer Security Institute reported that in 2007, 71% of companies surveyed used encryption for some of their data in transit, and 53% used encryption for some of their data in storage.[20] Encryption can be used to protect data "at rest", such as information stored on computers and storage devices (e.g. USB flash drives). In recent years, there have been numerous reports of confidential data, such as customers' personal records, being exposed through loss or theft of laptops or backup drives; encrypting such files at rest helps protect them if physical security measures fail.[21][22][23] Digital rights management systems, which prevent unauthorized use or reproduction of copyrighted material and protect software against reverse engineering (see also copy protection), is another somewhat different example of using encryption on data at rest.[24]

Encryption is also used to protect data in transit, for example data being transferred via networks (e.g. the Internet, e-commerce), mobile telephones, wireless microphones, wireless intercom systems, Bluetooth devices and bank automatic teller machines. There have been numerous reports of data in transit being intercepted in recent years.[25] Data should also be encrypted when transmitted across networks in order to protect against eavesdropping of network traffic by unauthorized users.[26]

Data erasure

[edit]Conventional methods for permanently deleting data from a storage device involve overwriting the device's whole content with zeros, ones, or other patterns – a process which can take a significant amount of time, depending on the capacity and the type of storage medium. Cryptography offers a way of making the erasure almost instantaneous. This method is called crypto-shredding. An example implementation of this method can be found on iOS devices, where the cryptographic key is kept in a dedicated 'effaceable storage'.[27] Because the key is stored on the same device, this setup on its own does not offer full privacy or security protection if an unauthorized person gains physical access to the device.

Limitations

[edit]Encryption is used in the 21st century to protect digital data and information systems. As computing power increased over the years, encryption technology has only become more advanced and secure. However, this advancement in technology has also exposed a potential limitation of today's encryption methods.

The length of the encryption key is an indicator of the strength of the encryption method.[28] For example, the original encryption key, DES (Data Encryption Standard), was 56 bits, meaning it had 2^56 combination possibilities. With today's computing power, a 56-bit key is no longer secure, being vulnerable to brute force attacks.[29]

Quantum computing uses properties of quantum mechanics in order to process large amounts of data simultaneously. Quantum computing has been found to achieve computing speeds thousands of times faster than today's supercomputers.[30] This computing power presents a challenge to today's encryption technology. For example, RSA encryption uses the multiplication of very large prime numbers to create a semiprime number for its public key. Decoding this key without its private key requires this semiprime number to be factored, which can take a very long time to do with modern computers. It would take a supercomputer anywhere between weeks to months to factor in this key.[31]However, quantum computing can use quantum algorithms to factor this semiprime number in the same amount of time it takes for normal computers to generate it. This would make all data protected by current public-key encryption vulnerable to quantum computing attacks.[32] Other encryption techniques like elliptic curve cryptography and symmetric key encryption are also vulnerable to quantum computing.[citation needed]

While quantum computing could be a threat to encryption security in the future, quantum computing as it currently stands is still very limited. Quantum computing currently is not commercially available, cannot handle large amounts of code, and only exists as computational devices, not computers.[33] Furthermore, quantum computing advancements will be able to be used in favor of encryption as well. The National Security Agency (NSA) is currently preparing post-quantum encryption standards for the future.[34] Quantum encryption promises a level of security that will be able to counter the threat of quantum computing.[33]

Attacks and countermeasures

[edit]Encryption is an important tool but is not sufficient alone to ensure the security or privacy of sensitive information throughout its lifetime. Most applications of encryption protect information only at rest or in transit, leaving sensitive data in clear text and potentially vulnerable to improper disclosure during processing, such as by a cloud service for example. Homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation are emerging techniques to compute encrypted data; these techniques are general and Turing complete but incur high computational and/or communication costs.

In response to encryption of data at rest, cyber-adversaries have developed new types of attacks. These more recent threats to encryption of data at rest include cryptographic attacks,[35] stolen ciphertext attacks,[36] attacks on encryption keys,[37] insider attacks, data corruption or integrity attacks,[38] data destruction attacks, and ransomware attacks. Data fragmentation[39] and active defense[40] data protection technologies attempt to counter some of these attacks, by distributing, moving, or mutating ciphertext so it is more difficult to identify, steal, corrupt, or destroy.[41]

The debate around encryption

[edit]The question of balancing the need for national security with the right to privacy has been debated for years, since encryption has become critical in today's digital society. The modern encryption debate[42] started around the '90s when US government tried to ban cryptography because, according to them, it would threaten national security. The debate is polarized around two opposing views. Those who see strong encryption as a problem making it easier for criminals to hide their illegal acts online and others who argue that encryption keep digital communications safe. The debate heated up in 2014, when Big Tech like Apple and Google set encryption by default in their devices. This was the start of a series of controversies that puts governments, companies and internet users at stake.

Integrity protection of Ciphertexts

[edit]Encryption, by itself, can protect the confidentiality of messages, but other techniques are still needed to protect the integrity and authenticity of a message; for example, verification of a message authentication code (MAC) or a digital signature usually done by a hashing algorithm or a PGP signature. Authenticated encryption algorithms are designed to provide both encryption and integrity protection together. Standards for cryptographic software and hardware to perform encryption are widely available, but successfully using encryption to ensure security may be a challenging problem. A single error in system design or execution can allow successful attacks. Sometimes an adversary can obtain unencrypted information without directly undoing the encryption. See for example traffic analysis, TEMPEST, or Trojan horse.[43]

Integrity protection mechanisms such as MACs and digital signatures must be applied to the ciphertext when it is first created, typically on the same device used to compose the message, to protect a message end-to-end along its full transmission path; otherwise, any node between the sender and the encryption agent could potentially tamper with it. Encrypting at the time of creation is only secure if the encryption device itself has correct keys and has not been tampered with. If an endpoint device has been configured to trust a root certificate that an attacker controls, for example, then the attacker can both inspect and tamper with encrypted data by performing a man-in-the-middle attack anywhere along the message's path. The common practice of TLS interception by network operators represents a controlled and institutionally sanctioned form of such an attack, but countries have also attempted to employ such attacks as a form of control and censorship.[44]

Ciphertext length and padding

[edit]Even when encryption correctly hides a message's content and it cannot be tampered with at rest or in transit, a message's length is a form of metadata that can still leak sensitive information about the message. For example, the well-known CRIME and BREACH attacks against HTTPS were side-channel attacks that relied on information leakage via the length of encrypted content.[45] Traffic analysis is a broad class of techniques that often employs message lengths to infer sensitive implementation about traffic flows by aggregating information about a large number of messages.

Padding a message's payload before encrypting it can help obscure the cleartext's true length, at the cost of increasing the ciphertext's size and introducing or increasing bandwidth overhead. Messages may be padded randomly or deterministically, with each approach having different tradeoffs. Encrypting and padding messages to form padded uniform random blobs or PURBs is a practice guaranteeing that the cipher text leaks no metadata about its cleartext's content, and leaks asymptotically minimal information via its length.[46]

See also

[edit]- Cryptosystem

- Cold boot attack

- Cryptographic primitive

- Cryptography standards

- Cyberspace Electronic Security Act (US)

- Dictionary attack

- Disk encryption

- Encrypted function

- Enigma machine

- Export of cryptography

- Geo-blocking

- Indistinguishability obfuscation

- Key management

- Multiple encryption

- Physical Layer Encryption

- Pretty Good Privacy

- Post-quantum cryptography

- Rainbow table

- Rotor machine

- Side-channel attack

- Substitution cipher

- Television encryption

- Tokenization (data security)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kessler, Gary (November 17, 2006). "An Overview of Cryptography". Princeton University.

- ^ a b Lennon, Brian (2018). Passwords: Philology, Security, Authentication. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780674985377.

- ^ a b "History of Cryptography". Binance Academy. Archived from the original on 2020-04-26. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- ^ "Caesar Cipher in Cryptography". GeeksforGeeks. 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- ^ "Wheel Cipher". www.monticello.org. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- ^ "M-94". www.cryptomuseum.com. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- ^ Hern, Alex (14 November 2014). "How did the Enigma machine work?". The Guardian.

- ^ Newton, Glen E. (7 May 2013). "The Evolution of Encryption". Wired. Unisys.

- ^ Johnson, Leighton (2016). "Security Component Fundamentals for Assessment". Security Controls Evaluation, Testing, and Assessment Handbook. pp. 531–627. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802324-2.00011-7. ISBN 978-0-12-802324-2.

- ^ Stubbs, Rob. "Classification of Cryptographic Keys". www.cryptomathic.com. Retrieved 2021-02-03.

- ^ "Chapter 3. Modular Arithmetic". www.doc.ic.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-10-11. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ "Symmetric-key encryption software". Archived from the original on 2022-03-10. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ Bellare, Mihir. "Public-Key Encryption in a Multi-user Setting: Security Proofs and Improvements." Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2000. p. 1.

- ^ "Public-Key Encryption – how GCHQ got there first!". gchq.gov.uk. Archived from the original on May 19, 2010.

- ^ Goldreich, Oded. Foundations of Cryptography: Volume 2, Basic Applications. Vol. 2. Cambridge university press, 2004.

- ^ Diffie, Whitfield; Hellman, Martin (1976), New directions in cryptography, vol. 22, IEEE transactions on Information Theory, pp. 644–654

- ^ Kelly, Maria (December 7, 2009). "The RSA Algorithm: A Mathematical History of the Ubiquitous Cryptological Algorithm" (PDF). Swarthmore College Computer Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Prasetyo, Deny; Widianto, Eko Didik; Indasari, Ike Pratiwi (6 September 2019). "Short Message Service Encoding Using the Rivest-Shamir-Adleman Algorithm". Jurnal Online Informatika. 4 (1): 39. doi:10.15575/join.v4i1.264.

- ^ Kirk, Jeremy (April 29, 2010). "Symantec buys encryption specialist PGP for $300M". Computerworld. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- ^ Robert Richardson, 2008 CSI Computer Crime and Security Survey at 19.i.cmpnet.com

- ^ Keane, J. (13 January 2016). "Why stolen laptops still cause data breaches, and what's being done to stop them". PCWorld. IDG Communications, Inc. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Castricone, D.M. (2 February 2018). "Health Care Group News: $3.5 M OCR Settlement for Five Breaches Affecting Fewer Than 500 Patients Each". The National Law Review. National Law Forum LLC. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Bek, E. (19 May 2016). "Protect Your Company from Theft: Self Encrypting Drives". Western Digital Blog. Western Digital Corporation. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "DRM". Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- ^ Fiber Optic Networks Vulnerable to Attack, Information Security Magazine, November 15, 2006, Sandra Kay Miller

- ^ "Data Encryption in Transit Guideline". Berkeley Information Security Office. Archived from the original on Dec 5, 2023.

- ^ "Welcome". Apple Support.

- ^ Abood, Omar G.; Guirguis, Shawkat K. (24 July 2018). "A Survey on Cryptography Algorithms". International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 8 (7). doi:10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7978.

- ^ "Encryption methods: An overview". IONOS Digital Guide. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ "Quantum computers vastly outperform supercomputers when it comes to energy efficiency". Physics World. 2020-05-01. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- ^ "How Shor's Algorithm Breaks RSA: A Quantum Computing Guide | SpinQ". www.spinquanta.com. Retrieved 2025-09-30.

- ^ Sharma, Moolchand; Choudhary, Vikas; Bhatia, R. S.; Malik, Sahil; Raina, Anshuman; Khandelwal, Harshit (3 April 2021). "Leveraging the power of quantum computing for breaking RSA encryption". Cyber-Physical Systems. 7 (2): 73–92. doi:10.1080/23335777.2020.1811384. S2CID 225312133.

- ^ a b Solenov, Dmitry; Brieler, Jay; Scherrer, Jeffrey F. (2018). "The Potential of Quantum Computing and Machine Learning to Advance Clinical Research and Change the Practice of Medicine". Missouri Medicine. 115 (5): 463–467. PMC 6205278. PMID 30385997.

- ^ "Post-Quantum Cybersecurity Resources". www.nsa.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2021-01-16.

- ^ Yan Li; Nakul Sanjay Dhotre; Yasuhiro Ohara; Thomas M. Kroeger; Ethan L. Miller; Darrell D. E. Long. "Horus: Fine-Grained Encryption-Based Security for Large-Scale Storage" (PDF). www.ssrc.ucsc.edu. Discussion of encryption weaknesses for petabyte scale datasets.

- ^ "The Padding Oracle Attack – why crypto is terrifying". Robert Heaton. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ^ "Researchers crack open unusually advanced malware that hid for 5 years". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ^ "New cloud attack takes full control of virtual machines with little effort". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2016-12-25.

- ^ Examples of data fragmentation technologies include Tahoe-LAFS and Storj.

- ^ "Moving Target Defense (MTD) – NIST CSRC Glossary". National Institute of Standards and Technology. Retrieved 2025-04-24.

- ^ CryptoMove Archived 2021-02-06 at the Wayback Machine is the first technology to continuously move, mutate, and re-encrypt ciphertext as a form of data protection.

- ^ Catania, Simone (2022-11-02). "The Modern Encryption Debate: What's at Stake?". CircleID.

- ^ "What is a Trojan Virus – Malware Protection – Kaspersky Lab US". 3 October 2023.

- ^ Kumar, Mohit (July 2019). "Kazakhstan Begins Intercepting HTTPS Internet Traffic Of All Citizens Forcefully". The Hacker News.

- ^ Sheffer, Y.; Holz, R.; Saint-Andre, P. (February 2015). Summarizing Known Attacks on Transport Layer Security (TLS) and Datagram TLS (DTLS) (Report).

- ^ Nikitin, Kirill; Barman, Ludovic; Lueks, Wouter; Underwood, Matthew; Hubaux, Jean-Pierre; Ford, Bryan (2019). "Reducing Metadata Leakage from Encrypted Files and Communication with PURBs" (PDF). Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETS). 2019 (4): 6–33. arXiv:1806.03160. doi:10.2478/popets-2019-0056. S2CID 47011059.

Further reading

[edit]- Fouché Gaines, Helen (1939), Cryptanalysis: A Study of Ciphers and Their Solution, New York: Dover Publications Inc, ISBN 978-0486200972

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Kahn, David (1967), The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing (ISBN 0-684-83130-9)

- Preneel, Bart (2000), "Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT 2000", Springer Berlin Heidelberg, ISBN 978-3-540-67517-4

- Sinkov, Abraham (1966): Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach, Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-622-0

- Tenzer, Theo (2021): SUPER SECRETO – The Third Epoch of Cryptography: Multiple, exponential, quantum-secure and above all, simple and practical Encryption for Everyone, Norderstedt, ISBN 978-3-755-76117-4.

- Lindell, Yehuda; Katz, Jonathan (2014), Introduction to modern cryptography, Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1466570269

- Ermoshina, Ksenia; Musiani, Francesca (2022), Concealing for Freedom: The Making of Encryption, Secure Messaging and Digital Liberties (Foreword by Laura DeNardis)(open access) (PDF), Manchester, UK: matteringpress.org, ISBN 978-1-912729-22-7, archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-06-02

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of encryption at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of encryption at Wiktionary Media related to Cryptographic algorithms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cryptographic algorithms at Wikimedia Commons