Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

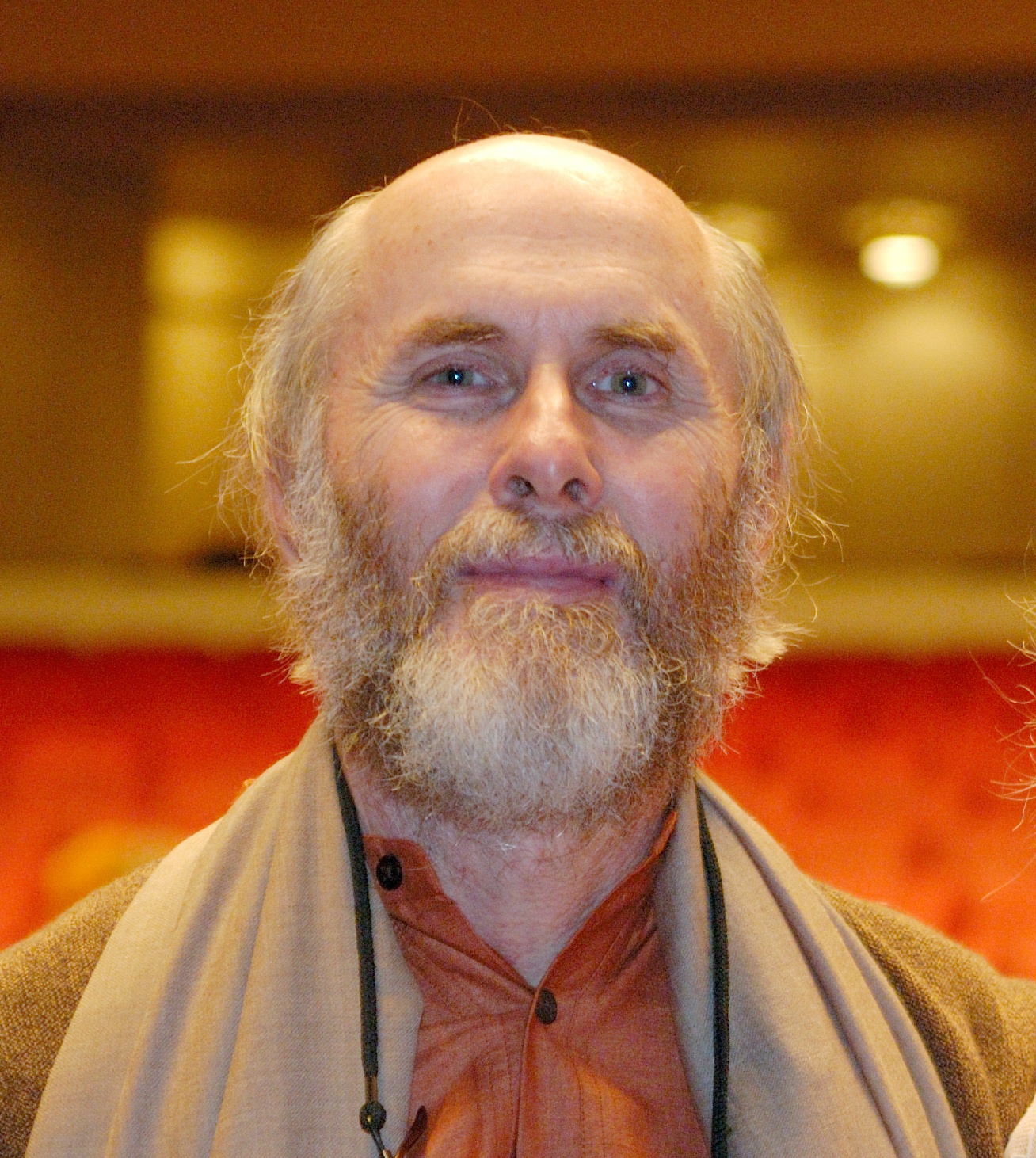

David Frawley

View on WikipediaDavid Frawley is an American Hindutva activist and a teacher of Hinduism.[1]

Key Information

He has written numerous books on topics spanning the Vedas, Hinduism, yoga, ayurveda and Hindu astrology.[2] In 2015 he was honored by the government of India with the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian award in India.[3]

A prominent ideologue of the Hindutva movement, he has also been accused of practicing historical revisionism.[4][5]

Early life and education

[edit]David Frawley was born to a Catholic family in Wisconsin and had nine siblings.[6] Frawley is largely an autodidact.[6] He studied ayurveda under B. L. Vashta of Mumbai for a span of about a decade, and obtained a "Doctor of Oriental Medicine" degree via a correspondence course from the International Institute of Chinese Medicine, Santa Fe, New Mexico,[5] a school for acupuncture which closed in 2003 due to "administrative and governance irregularities" and financial problems."[7]

Frawley is the founder and the sole instructor at the American Institute of Vedic Studies at Santa Fe, New Mexico[8][9] and is a former president of the American Council of Vedic Astrology.[10] He also previously taught Chinese herbal medicine and western herbology.[11]

Views and reception

[edit]Views

[edit]Frawley rejects the Indo-Aryan migration theory in favor of the Indigenous Aryans theory, accusing his opponents of having a “European missionary bias”.[12][13] In the book In Search of the Cradle of Civilization (1995), Frawley along with Georg Feuerstein and Subhash Kak has rejected the widely supported Indo-Aryan migration, rhetorically calling it the Aryan Invasion Theory, an outdated and inaccurate term, and supported the Indigenous Aryans theory. Frawley also criticizes the 19th-century racial interpretations of Indian prehistory, and went on to reject the theory of a conflict between invading caucasoid Aryans and Dravidians.[14]

In the sphere of market-economics, Frawley opposes socialism, stating that such policies have reduced citizens to beggars.[15] He is a practitioner of Ayurveda,[16] and recommends the practice of ascetic rituals along with moral purification as indispensable parts of the Advaita tradition.[17]

Reception

[edit]Popular reception

[edit]While being rejected by academia, he has been successful in the popular market; according to Bryant, his works are clearly directed and articulated at such audiences.[18][6][5] He's been a prominent voice in the introduction of Ayurvedic medicine and Vedic astrology among a western, nonmedical trained audience.[5][19][20][21] According to Edwin Bryant, he is "well-received" by "the Indian community,"[8] noting that a Westerner rejecting the Aryan Migration Theory has an obvious appeal in India and Frawley (along with Koenraad Elst) fits in it, perfectly.[22] Frawley commands a significant following on Twitter, as well.[6]

Academia

[edit]Hindutva

[edit]He has been described as a prominent figure of the Hindutva movement[23][24][25][10][26][27] and numerous scholars have also described him as a Hindutva ideologue and apologist.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][15] He has been widely described as practicing historical revisionism.[4][5] Martha Nussbaum and others consider him to be the most determined opponent to the theory of Indo-Aryan migrations.[35][36]

Meera Nanda asserts Frawley to be a member of the Hindu far right, who decries Islam and Christianity as religions for the lower intellects[37] and whose works feature a Hindu Supremacist spin.[38][39] Sudeshna Guha of Cambridge University notes him to be a sectarian non-scholar and as a proponent of a broader scheme for establishing a nationalist history.[40] Irfan Habib rejected considering Frawley as a scholar, and instead, noted him to be a Hindutva pamphleteer, who "telescoped the past to serve the present" and was not minimally suitable of being defined as a scholar, of any kind.[41][6] Bryant notes him to be an unambiguously pro-Hindu scholar.[18] Peter Heehs deems of him to be part of a group of reactionary orientalists, who professed an avid dislike for the Oriental-Marxist school of historiography and hence, chose to rewrite the history of India but without any training in relevant disciplines; he also accused Frawley of misappropriating Aurobindo's nuanced stance on the Indigenous Aryans hypothesis.[42]

Bruce Lincoln attributes Frawley's ideas to "parochial nationalism", terming them "exercises in scholarship (= myth + footnotes)", where archaeological data spanning several millennia is selectively invoked, with no textual sources to control the inquiry, in support of the theorists' desired narrative.[43] His proposed equivalence of Ayurveda with vedic healing traditions has been rejected by Indologists and David Hardiman considers Frawley's assertion to be part of a wider Hindu-nationalist quest.[44] Joseph Alter notes that his writings 'play into the politics of nationalism' and remarks of them to be controversial from an academic locus.[45]

Book reviews

[edit]In a review of Hymns from the Golden Age: Selected Hymns from the Rig Veda with Yogic Interpretation for the Journal of the American Oriental Society, Richard G. Salomon criticized Frawley's "fanciful" approach to stand in complete contrast to the available linguistic and scholarly evidence, and perpetuated Vedic myths in what seemed to be a bid to attract readers for the recreation of the ancient spiritual kingdom of the Aryans.[46]

A review by M. K. Dhavalikar in Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute called In Search of the Cradle of Civilization a "beautifully printed" contribution that made a strong case for their indigenous theory against the supposed migratory hypotheses but chose to remain silent on certain crucial aspects which need to be convincingly explained.[47] Prema Kurien noted that the book sought to distinguish expatriate Hindu Americans from other minority groups by demonstrating their superior racial and cultural ties with the Europeans.[48]

Dhavalikar also reviewed The Myth of the Aryan Invasion of India and found it to be unsupported by archaeological evidence.[36] Irfan Habib criticized Frawley's invoking the Sarasvati River in the book as an assault against common sense.[49][clarification needed]

Honors and influences

[edit]In 2015, the South Indian Education Society (SIES) in Mumbai, India, an affiliate of Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, conferred upon him their special "National Eminence Award" as an “international expert in the fields of Ayurveda, Yoga, and Vedic Astrology.”[50] On 26 January 2015, the Indian Government honored Frawley with the Padma Bhushan award.[51]

Referring to his book Yoga and Ayurveda, Frawley is mentioned as one of the main yoga teachers of Deepak Chopra and David Simon in their book, the Seven Spiritual Laws of Yoga (2005).[52] In 2015, Chopra said of Frawley's book, Shiva, the Lord of Yoga, "Vamadeva Shastri has been a spiritual guide and mentor of mine for several decades. For anyone who is serious about the journey to higher divine consciousness, this book is yet another jewel from him."[53]

Selected publications

[edit]Hinduism and Indology

[edit]- Hymns from the Golden Age: Selected Hymns from the Rig Veda With Yogic Interpretation. Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 1986. ISBN 8120800729.

- In Search of the Cradle of Civilization (1995), with Georg Feuerstein and Subhash Kak

- Wisdom of the Ancient Seers: Mantras of the Rig Veda. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd), 1999. ISBN 8120811593.

- Arise Arjuna: Hinduism Resurgent in a New Century. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018. ISBN 9388134982.

- Awaken Bharata: A Call for India’s Rebirth. Bloomsbury India, 2018. ISBN 9388271009.

- What Is Hinduism?. Bloomsbury India, 2018. ISBN 9789388038638.

Yoga, Vedanta and Ayurveda

[edit]- Ayurvedic Healing. Passage Press, 1989. ISBN 1878423002.

- Ayurveda and the Mind: The Healing of Consciousness. Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 2005. ISBN 812082010X.

Co-authored

[edit]- The Yoga of Herbs: An Ayurvedic Guide to Herbal Medicine. Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 2004. ISBN 8120820347.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chetan Bhatt (2000). "Hindu Nationalism and Indigenous 'Neo-racism'". In Back, Les; Solomos, John (eds.). Theories of Race and Racism: A Reader. Psychology Press. pp. 590–591. ISBN 9780415156714. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

It is important to note the marriage between far-right-wing Hindutva ideology and western New Ageism in the works of writers like David Frawley (1994, 1995a, 1995b) who is both a key apologist for the Hindutva movement and the author of various New Age books on Vedic astrology, oracles and yoga

- ^ "David Frawley is the American hippy who became RSS's favourite western intellectual". ThePrint. 17 November 2018.

- ^ "The unusual story of David Frawley aka Vamadeva Sastri". Deccan Herald. 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b Shrimali, Krishna Mohan (July 2007). "Writing India's Ancient Past". Indian Historical Review. 34 (2): 171–188. doi:10.1177/037698360703400209. ISSN 0376-9836. S2CID 140268498.

- ^ a b c d e Wujastyk, Dagmar; Smith, Frederick M. (2013-09-09). "Introduction". Modern and Global Ayurveda: Pluralism and Paradigms. SUNY Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-7914-7816-5.

- ^ a b c d e Bamzai, Kaveree (2018-11-17). "David Frawley is the American hippy who became RSS's favourite western intellectual". ThePrint. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ Acupuncture Today – October, 2003, Vol. 04, Issue 10, International Institute of Chinese Medicine Closes

- ^ a b Bryant, Edwin (2001-09-06). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 347. ISBN 9780195137774.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dagmar; Smith, Frederick M. (2013-09-09). "An Overview of the Education and Practice of Global Ayurveda". Modern and Global Ayurveda: Pluralism and Paradigms. SUNY Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-7914-7816-5.

- ^ a b Searle-Chatterjee, Mary (January 2000). "'World religions' and 'ethnic groups': do these paradigms lend themselves to the cause of Hindu nationalism?". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 23 (3): 497–515. doi:10.1080/014198700328962. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 145681756.

- ^ Michael Tierra (1988). David Frawley (ed.). Planetary Herbology. Lotus Press. ISBN 978-0941524278.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Sumathi (June 2001). "Remains of the race: Archaeology, nationalism, and the yearning for civilisation in the Indus valley". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 38 (2): 105–145. doi:10.1177/001946460103800201. ISSN 0019-4646. S2CID 145756604.

- ^ Benedict M. Ashley, O. P. (2006). "Notes". Way Toward Wisdom, The: An Interdisciplinary and Intercultural Introduction to Metaphysics. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 460. ISBN 9780268074692.

- ^ Arvidsson 2006:298 Arvidsson, Stefan (2006), Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science, translated by Sonia Wichmann, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b Pathak, Pathik (2008). "Saffron Semantics: The Struggle to Define Hindu Nationalism". The Future of Multicultural Britain: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 73–74, 80. ISBN 9780748635443. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1r27ks. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ Warrier, Maya (March 2011). "Modern Ayurveda in Transnational Context: Modern Ayurveda in Transnational Context". Religion Compass. 5 (3): 80–93. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2011.00264.x.

- ^ Lucas, Phillip Charles (2014). "Non-Traditional Modern Advaita Gurus in the West and Their Traditional Modern Advaita Critics". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 17 (3): 6–37. doi:10.1525/nr.2014.17.3.6. ISSN 1092-6690. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2014.17.3.6.

- ^ a b Bryant, Edwin (2001-09-06). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture : The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press. p. 291. ISBN 9780195169478. OCLC 697790495.

- ^ "Yoga Journal". Yoga Journal. 28 August 2007. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Philip Goldberg (2010). American Veda: How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. Harmony Books. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0-385-52134-5.

- ^ Anand, Shilpa Nair (Feb 28, 2014). "An Enlightened Path". The Hindu.

- ^ Bryant, Edwin (2001-09-06). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 292. ISBN 9780195137774.

- ^ Gilmartin, David; Lawrence, Bruce B (2002). Beyond Turk and Hindu: rethinking religious identities in Islamicate South Asia. New Delhi: India Research Press. ISBN 9788187943341. OCLC 52254519.

- ^ Lal, Vinay (1999). "The Politics of History on the Internet: Cyber-Diasporic Hinduism and the North American Hindu Diaspora". Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies. 8 (2): 137–172. doi:10.1353/dsp.1999.0000. ISSN 1911-1568. S2CID 144343833.

- ^ Tripathi, Salil (October 2002). "The End of Secularism". Index on Censorship. 31 (4): 160–166. doi:10.1080/03064220208537150. ISSN 0306-4220. S2CID 146826096.

- ^ Chaudhuri, Arun (June 2018). "India, America, and the Nationalist Apocalyptic". CrossCurrents. 68 (2): 216–236. doi:10.1111/cros.12309. ISSN 0011-1953. S2CID 171592481.

- ^ Lal, Vinay (2003). "North American Hindus, the Sense of History, and the Politics of Internet Diasporism". In Lee, Rachel C.; Wong, Sau-ling Cynthia (eds.). Asian America.Net : Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Cyberspace. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780203957349.

- ^ Mukta, Parita (2000-01-01). "The public face of Hindu nationalism". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 23 (3): 442–466. doi:10.1080/014198700328944. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 144284403.

- ^ Koertge. (2005-08-04). Scientific Values and Civic Virtues. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195172256. OCLC 474649157.

- ^ Pathak, Pathik (2012). The Future of Multicultural Britain: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780748635467. OCLC 889952434.

- ^ Kuruvachira, Jose (2006). Hindu Nationalists of Modern India: A Critical Study of the Intellectual Genealogy of Hindutva. Rawat Publications. ISBN 9788170339953.

- ^ Bhatt, Chetan (2000-01-01). "Dharmo rakshati rakshitah : Hindutva movements in the UK". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 23 (3): 559–593. doi:10.1080/014198700328999. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 144085595.

- ^ Chadha, Ashish (February 2011). "Conjuring a river, imagining civilisation". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 45 (1): 55–83. doi:10.1177/006996671004500103. ISSN 0069-9667. S2CID 144701033.

- ^ Back, Les; Solomos, John; Solomos, Professor of Sociology in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science John (2000). Theories of Race and Racism: A Reader. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415156714.

- ^ Nussbaum, Martha Craven (2008). The Clash Within : Democracy, Religious Violence, and India's Future. Harvard University Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780674030596. OCLC 1006798430.

- ^ a b Dhavalikar, M. K. (1997). "Review of THE MYTH OF INDIA; ARYAN INVASION OF INDIA: THE MYTH AND THE TRUTH". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 78 (1/4): 343–344. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41694966.

- ^ NANDA, MEERA (2011). "Ideological Convergences: Hindutva and the Norway Massacre". Economic and Political Weekly. 46 (53): 61–68. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 23065638.

- ^ Nanda, Meera (2009). "Hindu Triumphalism and the Clash of Civilisations". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (28): 106–114. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 40279263.

- ^ Nanda, Meera (2011). The god market : how globalization is making India more Hindu. Monthly Review Press. p. 162. ISBN 9781583672501. OCLC 731901376.

- ^ Guha, Sudeshna (2005). "Negotiating Evidence: History, Archaeology and the Indus Civilisation". Modern Asian Studies. 39 (2): 399–426. doi:10.1017/S0026749X04001611. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 3876625. S2CID 145463239.

- ^ "Why Hindutva's foreign-born cheerleaders are so popular - Times of India". The Times of India. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- ^ Heehs, Peter (May 2003). "Shades of Orientalism: Paradoxes and Problems in Indian Historiography". History and Theory. 42 (2): 169–195. doi:10.1111/1468-2303.00238. ISSN 0018-2656.

- ^ Bruce Lincoln (1999). Theorizing Myth: Narrative, Ideology, and Scholarship. University of Chicago Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-226-48201-9.

- ^ Hardiman, David (2009). "Indian Medical Indigeneity: From Nationalist Assertion to the Global Market" (PDF). Social History. 34 (3): 263–283. doi:10.1080/03071020902975131. ISSN 0307-1022. JSTOR 25594366. S2CID 144288544.

- ^ Alter, Joseph S. (2011). "Notes". Asian Medicine and Globalization. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 156. ISBN 9780812205251.

- ^ Salomon, Richard (1989). "Review of Hymns from the Golden Age: Selected Hymns from the Rig Veda with Yogic Interpretation; Pinnacles of India's Past: Selections from the Rgveda". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 109 (3): 456–457. doi:10.2307/604160. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 604160.

- ^ M. K. Dhavalikar (1996). "Untitled [review of In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India, by Georg Feuerstein, Subhash Kak, & David Frawley]". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 77 (1/4). Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute: 326–327. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41702199.

- ^ Kurien, Prema A. (2007). A place at the multicultural table the development of an American Hinduism. Rutgers University Press. pp. 242. ISBN 9780813540559. OCLC 703221465.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (2001). "Imaging River Sarasvati: A Defence of Commonsense". Social Scientist. 29 (1/2): 46–74. doi:10.2307/3518272. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3518272.

- ^ "Suresh Prabhu gets SIES award for national eminence". Economic Times. Retrieved 27 Dec 2015.

- ^ "Padma Awards 2015". Press Information Bureau. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Deepak Chopra; David Simon (2005). Seven Spiritual Laws of Yoga. Wiley. p. 200. ISBN 978-0471736271.

- ^ David Frawley (2015). Shiva, the Lord of Yoga. Lotus Press. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-9406-7629-9.

External links

[edit]David Frawley

View on GrokipediaPersonal Background

Early Life and Education

David Frawley was born on September 21, 1950, in La Crosse, Wisconsin, to a Catholic family as one of nine siblings.[4] [5] Raised in a traditional Catholic household, he grew up in a Midwestern American environment during the post-World War II era.[6] [7] Frawley's formal Western education is not extensively documented, and he is characterized as largely self-taught or an autodidact in his early pursuits.[8] During the 1960s, amid the countercultural movement, he developed an interest in Eastern philosophies and spirituality, reading widely on Hinduism and related traditions.[6] By 1970, he began systematic self-study of Vedic knowledge, influenced by figures such as Ramana Maharshi, marking the start of his independent scholarly engagement with Indian wisdom systems.[1]Professional Development

Transition to Vedic Studies

Born in 1950 to a Catholic family in the United States, David Frawley initially grew up within a Christian framework but encountered Indian philosophy in the late 1960s amid broader explorations of Eastern spiritual traditions, including Buddhism, Taoism, and Sufism.[6] Vedanta emerged as the most resonant path for him, surpassing other systems due to its emphasis on self-inquiry and universal principles, leading him to distance himself from Christianity—briefly identifying as an atheist before informally embracing Hinduism through personal sadhana rather than formal ritual.[6] By 1970, Frawley had begun dedicated Vedic research, influenced early on by figures such as Ramana Maharshi and Sri Aurobindo, whose teachings he encountered through writings and later interactions, including meetings with Aurobindo's disciple M.P. Pandit in 1979.[1] In the early 1970s, he deepened his studies into core Vedic disciplines like the Vedas, Ayurveda, and Jyotish (Vedic astrology), producing initial translations and publications on these texts starting in 1977, marking a shift from self-directed reading to systematic scholarly engagement.[1] This period reflected an interdisciplinary synthesis, drawing on his prior interest in Western psychology to interpret Vedic knowledge through a modern lens, though he prioritized empirical spiritual practice over institutional Western education in these fields.[1] Frawley's formal commitment intensified in the 1980s; he adopted the spiritual name Pandit Vamadeva Shastri, signifying his role as a Vedic teacher, and founded the Vedic Research Center in 1980, which evolved into the American Institute of Vedic Studies by 1988 to institutionalize his teachings on Yoga, Ayurveda, and Vedanta.[1] [6] This transition was self-initiated without a single guru's direct ordination but guided by correspondence with saints like Anandamayi Ma (1976–1982) and later mentorships, such as with Sadguru Sivananda Murty in 1994, underscoring a gradual realization that his life practices aligned with Vedic Dharma, as detailed in his 2000 autobiography How I Became a Hindu: My Discovery of Vedic Dharma.[1]Establishment of Institutions and Teaching

In 1980, David Frawley established the Vedic Research Center to support his ongoing studies of the Vedas, which he had pursued since 1970, and to facilitate his writings on Indian publications beginning in 1977.[9] This initial institution laid the groundwork for disseminating Vedic knowledge in the West, focusing on research into ancient texts and their applications.[1] By 1988, Frawley expanded the Vedic Research Center into the American Institute of Vedic Studies (AIVS), based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to promote integrated teachings in Yoga, Vedanta, Ayurveda, and Vedic Astrology as interconnected aspects of Vedic science.[9] [10] The AIVS operates primarily as an online educational platform, offering structured courses, resources, and consultations worldwide, with Frawley serving as the primary instructor alongside Yogini Shambhavi.[11] Key programs include the Ayurvedic Healing Course, which covers dosha-based healing practices, and specialized modules on Vedic astrology and yogic meditation, drawing from Frawley's expertise as a recognized Vedacharya.[12] Frawley's teaching extends beyond AIVS through seminars, retreats, and workshops on topics such as psychological health via Ayurvedic principles, including management of anxiety and depression through doshas, gunas, and ojas enhancement.[13] These activities emphasize practical application of Vedic methods, often held in intimate settings in Europe and the United States, integrating yoga postures, pranayama, and tantric practices.[14] As director, Frawley maintains AIVS's focus on self-study and teacher training, attracting students globally while prioritizing empirical alignment with classical texts over modern reinterpretations.[15]Scholarly Contributions

Advancements in Ayurveda, Yoga, and Jyotish

Frawley has advanced the understanding and application of Ayurveda in the West through extensive authorship and teaching, emphasizing its integration with Vedic spirituality and modern health practices. He authored Ayurveda: Nature's Medicine in 1994, which elucidates Ayurvedic principles such as dosha balance and herbal therapies while connecting them to broader self-healing methodologies derived from classical texts like the Charaka Samhita.[16] His work includes detailed explorations of marma points—energy centers used in Yogic healing—as outlined in Ayurveda and Marma Therapy, promoting their therapeutic use for physical and psychological ailments based on empirical observations from Vedic traditions.[17] Recognized as a senior Ayurvedacharya, Frawley pursued advanced studies in Ayurveda for nearly a decade under traditional practitioners, applying these to contemporary contexts like stress management and preventive care.[8] [18] In Yoga, Frawley has contributed by reframing its Vedic foundations beyond physical postures, focusing on prana regulation and inner realization to address mental afflictions. He examined the five pranas (vital airs)—prana, apana, vyana, udana, and samana—in depth across Hatha, Raja, and meditative Yoga traditions, linking them to Ayurvedic diagnostics for holistic balance, as detailed in his teachings and writings.[18] His book Yoga and Ayurveda: Self-Healing and Self-Realization (1999) advocates reuniting these sister sciences, arguing that Yoga's ashtanga limbs require Ayurvedic lifestyle support to mitigate suffering, drawing from primary texts like Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and Upanishadic sources.[19] Through the American Institute of Vedic Studies, founded in 1987, he developed online courses combining Yoga with mantra and meditation, emphasizing experiential verification over doctrinal adherence.[20] Frawley holds a D.Litt. in Yoga and Vedic Studies from S-VYASA University, awarded for his scholarly synthesis of these disciplines.[18] Frawley's advancements in Jyotish (Vedic astrology) center on its role as a predictive and remedial tool intertwined with Ayurveda and karma analysis, rather than fatalism. His seminal work Astrology of the Seers (first published 1991) provides a comprehensive guide to Jyotish principles, including planetary influences, nakshatras, and dashas, grounded in texts like the Brihat Parashara Hora Shastra, and applies them to personal healing and life cycles.[21] He pioneered the integration of Jyotish with Ayurvedic remedies, such as using gemstones and mantras to mitigate doshic imbalances indicated by birth charts, as taught in his Ayurvedic Astrology course.[22] This approach views Jyotish not merely for event prediction but for long-term self-awareness and karmic navigation, supported by his textual research linking stellar positions to physiological and psychological states.[23] Through consultations and writings, Frawley has emphasized Jyotish's empirical basis in observable correlations between celestial cycles and human affairs, fostering its practical use in Western contexts.[24]Interpretations of Vedic Texts and Indology

David Frawley has emphasized yogic and spiritual interpretations of Vedic texts, particularly the Rigveda, viewing them as mantric teachings that require insight into inner practices like meditation and self-realization rather than solely linguistic or historical analysis. In works such as Wisdom of the Ancient Seers: Mantras of the Rig-Veda (1994), he translates and explicates over eighty hymns dedicated to deities including Indra, Agni, and Soma, highlighting their relevance to Yoga, Kundalini processes, and cosmic symbolism, such as references to astronomical divisions like the 360-degree zodiac evident in hymns attributed to the rishi Dirghatamas.[25][26] He argues that the Vedas encode profound occult and spiritual secrets, including Soma not merely as a ritual plant but as an inner elixir accessed through yogic discipline, drawing on over 400 textual references to link Vedic hymns directly to Vedantic self-realization and practices later elaborated in Yoga traditions.[27][28] Frawley's approach integrates Vedic studies with Ayurveda, Jyotish (Vedic astrology), and broader dharmic sciences, positing the Vedas as a unified knowledge system originating in India around 3100 BCE, contemporaneous with the Harappan civilization and the Sarasvati River's prominence. He established the Vedic Research Center in 1980 to advance translations and interpretations of the Rigveda and other Samhitas, producing over 1,000 pages of research published through institutions like the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. This framework rejects compartmentalized Western academic methods, advocating instead for a holistic reading grounded in rishi traditions and India's geographical-cultural continuity.[1][15] In Indology, Frawley critiques 19th- and 20th-century Western scholarship for "Europeanizing" the Vedas through colonial lenses, such as prioritizing Proto-Indo-European linguistic ties and imposing mythologies that disconnect the texts from their Indian spiritual context. He contends that interpretations by scholars like Max Müller distorted Vedic deities and rituals by analogizing them to European paganism while dismissing mantra science, Yoga, and indigenous origins, often to support narratives of cultural superiority or invasion. Central to this is his rejection of the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT), detailed in The Myth of the Aryan Invasion of India (1994), where he marshals archaeological, genetic, astronomical, and textual evidence—such as the absence of destruction layers in Harappan sites and Vedic references to riverine ecology matching the dried Sarasvati—to argue for an endogenous Vedic-Harappan continuity dating back millennia, rather than an exogenous migration around 1500 BCE.[29][30][8] Frawley positions Indology as an extension of Orientalism that undervalues India's civilizational antiquity, urging a reclamation of Vedic history through traditional Indic lenses to reveal its intellectual and yogic primacy, including mathematical cycles like the yuga system spanning billions of years and harmonic divisions in Vedic astronomy. His interdisciplinary synthesis, spanning over 40 books and 300 articles, promotes Vedic texts as foundational to global spiritual heritage, challenging academia's materialistic biases and advocating for recognition of Sanskrit's developmental primacy in language evolution.[1][31][32]Key Intellectual Positions

On Hindu History and Identity

Frawley maintains that Vedic civilization arose indigenously in the Indian subcontinent, with its core centered on the Sarasvati-Drishadvati river region, rather than through external migrations or invasions.[30] He critiques the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT), originally proposed in the 19th century, as a construct lacking archaeological corroboration for widespread destruction or foreign incursions around 1500 BCE, and rebranded in modern scholarship as the Aryan Migration Theory without sufficient revision of outdated premises.[30] Drawing on Vedic texts like the Rig Veda, Frawley interprets geographical references—such as the prominence of the Sarasvati River, which dried up circa 1900 BCE—as evidence of a continuous cultural evolution from pre-Harappan urban centers like Rakhigarhi and Dholavira to later Vedic society, predating alleged Indo-European arrivals.[30] Supporting his position, Frawley references genetic analyses, including studies by Hemphill et al. (1991), indicating skeletal and population continuity in northwest India from 1900 to 800 BCE, with no markers of mass replacement by steppe pastoralists.[30] Linguistically, he proposes an indigenous "Sanskritization" process for the spread of Indo-European elements, viewing Vedic Sanskrit as a highly inflected, regionally developed language incompatible with nomadic origins.[30] These arguments, elaborated in works like The Myth of the Aryan Invasion of India (1994, updated editions) and The Rig Veda and the History of India (2001), challenge Eurocentric frameworks that portray ancient India as derivative, emphasizing instead a dharmic civilization spanning over 5,000 years with roots in sophisticated spiritual, astronomical, and ecological knowledge.[30][33] Frawley attributes distortions in Hindu historical narratives to colonial-era scholarship, which depicted India as primitive and invasion-prone to justify British rule, compounded by post-independence Marxist historiography that prioritized class conflict over cultural continuity and aligned with external powers during events like the 1962 Sino-Indian War.[34] He advocates rewriting Indian history to integrate Vedic literature—such as the Mahabharata, the world's longest epic predating 1000 BCE—with archaeological evidence from Sarasvati sites, fostering national pride and countering what he sees as secularist dismissals of such efforts as communal.[34] This revisionism, he argues, reveals Hinduism not as a late synthesis but as the foundational matrix of Indian identity, encompassing yoga, Vedanta, and reverence for Bharat as a sacred geography.[34] Regarding Hindu identity, Frawley urges adherents to openly affirm it as a bulwark against de-Hinduization trends, including missionary activities and intellectual denigration that portray Hindu practices as superstitious or exclusionary.[35] In How I Became a Hindu (2000), he recounts his own embrace of Vedic Dharma from a Western background, framing it as a universal spiritual science rather than mere ritualism, and critiques efforts to discourage Hindu self-identification in both India and the West.[36] Frawley posits Hindu identity as inherently inclusive yet rooted in inner transformation and dharma, transcending narrow religious labels to include global seekers of Vedantic wisdom, while warning that unasserted it risks erosion amid pluralistic pressures.[35][37]On Politics, Economics, and Global Critiques

Frawley has consistently criticized Nehruvian socialism in India, contending that it hindered economic progress for decades by prioritizing state control over individual enterprise and traditional Hindu values. He attributes the roots of Indian socialism to a form of Hinduphobia, linking it to leftist ideologies that rejected Vedic thought and Upanishadic principles in favor of imported materialist frameworks.[38] In his view, such policies fostered dependency and cultural alienation, contrasting sharply with pre-colonial India's economic prominence, where its GDP exceeded Britain's before European interventions diminished its global share.[39] Regarding broader economic paradigms, Frawley rejects both unchecked capitalism and socialism as insufficient for elevating human consciousness, arguing they entangle societies in material dualities without addressing spiritual or dharmic dimensions like artha (legitimate wealth pursuit) balanced against self-interest (swartha).[40] He critiques modern consumerism as self-destructive, where the consumer ultimately becomes consumed by endless desires, diverging from Vedic economics that integrate prosperity with ecological harmony and inner fulfillment.[41][42] Frawley's political commentary emphasizes reclaiming Hindu identity against distorted historical narratives, such as the Aryan Invasion Theory, which he sees as perpetuated by colonial and leftist biases to undermine India's indigenous civilizational continuity.[31] He challenges India's secular framework as inherently anti-Hindu, enabling minority appeasement at the expense of majority cultural rights, and dismisses the left-right binary in Indian politics as a Marxist construct that labels Hindu assertion as extremist.[43] On global ideologies, Frawley positions Marxism as the most pernicious colonial force, surpassing even direct imperial rule in eroding traditional cultures through atheistic materialism and cultural revolutions, as exemplified in China's Maoist era.[44] He regards it as devoid of dharma, spirituality, or recognition of higher consciousness, rendering it antithetical to Sanatana Dharma's emphasis on universal consciousness and ethical pluralism.[45] Similarly, he critiques Islam's expansionist tendencies, associating jihadist threats with unreformed doctrines that prioritize conquest over coexistence, urging a Hindu response that highlights dharmic tolerance against monotheistic intolerance.[46] Frawley warns against excusing Islamic terrorism through socioeconomic excuses while blaming Hindu society, framing these critiques within a civilizational clash where dharmic traditions face existential challenges from Abrahamic and Marxist universalisms.[47]Publications

Major Works on Hinduism and Vedanta

Frawley's explorations of Hinduism emphasize its status as Sanatana Dharma, an eternal tradition rooted in Vedic wisdom, self-realization, and universal truth, distinct from Abrahamic faiths in its non-dogmatic approach to spirituality.[2] In How I Became a Hindu: My Discovery of Vedic Dharma (2000), he recounts his transition from a Western Christian background to embracing Hindu Dharma through study of the Vedas, Yoga, and Ayurveda, highlighting themes of Vedic universality, critiques of missionary distortions of Hinduism, and the need for Hindus to assert their tradition's philosophical depth against colonial-era misrepresentations.[36] The work positions Hinduism as a comprehensive spiritual science applicable globally, urging Western seekers to recognize its foundational role in Yoga and Vedanta practices.[48] What Is Hinduism?: A Guide for the Global Mind (2019) presents Hinduism through a question-and-answer format addressing core doctrines, rituals, and societal implications, portraying it as a system of eternal laws (dharma) promoting cosmic harmony, self-inquiry, and tolerance of diverse paths to the divine.[49] Frawley argues that Hinduism's emphasis on inner realization over external conversion counters modern secular critiques, drawing on Vedic texts to affirm its adaptability to contemporary challenges like materialism and cultural erosion.[50] Universal Hinduism: Sanatana Dharma (2010) extends this by advocating a revival of Vedic principles for global spiritual renewal, critiquing syncretic dilutions and emphasizing Hinduism's innate pluralism as a model for interfaith dialogue without compromise of core truths.[2] On Vedanta specifically, Vedantic Meditation: Lighting the Flame of Awareness (2000) outlines the philosophy's meditative practices aimed at transcending ego-bound perception to realize the non-dual Self (Atman-Brahman).[51] Frawley details techniques for calming the mind, inquiring into the nature of consciousness, and integrating supportive disciplines like pranayama and mantra, while identifying ignorance of the true Self as the root of suffering, to be eradicated through direct discernment rather than ritual alone.[52] This work synthesizes Upanishadic teachings with practical guidance, positioning Vedanta as the culmination of Vedic knowledge for achieving liberating wisdom (jnana). Additional contributions include Arise Arjuna: Hinduism and the Modern World (1995), which applies the Bhagavad Gita's call to dharma in addressing secularism, nationalism, and Hindu revivalism, and Hinduism: The Eternal Tradition (2000), a collection of reflections on Sanatana Dharma's timeless insights into karma, reincarnation, and divine unity.[53] These texts collectively underscore Frawley's view of Hinduism and Vedanta as integrative frameworks for personal and civilizational resilience, grounded in empirical self-observation over faith-based assertions.[54]Books on Health Sciences and Astrology

Frawley's works on health sciences emphasize Ayurveda's holistic approach to physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, often integrating it with Yoga practices for self-healing. In Ayurvedic Healing: A Comprehensive Guide, published in 1989, he details treatments for over eighty ailments ranging from common colds to cancer, drawing on classical Ayurvedic texts while adapting principles for contemporary use.[55] His book Ayurveda and the Mind: The Healing of Consciousness, first released in the 1990s and revised in 2005, explores psychological healing through Ayurvedic doshas, incorporating diet, mantra, meditation, and impressions to address subconscious to superconscious levels.[56] Yoga and Ayurveda: Self-Healing and Self-Realization presents the two systems as complementary for optimal vitality and awareness, with practical guidance on asanas tailored to individual constitutions.[57]- Yoga of Herbs: An Ayurvedic Guide to Herbal Medicine (revised 2001): Outlines herbal remedies aligned with doshic balances, emphasizing preventive health and therapeutic applications in Yoga contexts.[58]

Reception and Impact

Governmental and Popular Recognition

In 2015, the Government of India awarded David Frawley the Padma Bhushan, the third-highest civilian honor, for distinguished service in literature and education, specifically recognizing his efforts in advancing Vedic knowledge systems, including Yoga, Ayurveda, and Jyotish, to global audiences.[1] The award was announced on January 25, 2015, as part of the Republic Day honors, and presented by President Pranab Mukherjee at Rashtrapati Bhavan later that year.[3] Among the 20 Padma Bhushan recipients that year, Frawley was one of few non-Indians selected, highlighting the exceptional nature of the recognition for a Western-born scholar.[61] Frawley's governmental acknowledgment extends to affiliations with Indian institutions promoting traditional sciences, though primarily through the Padma honor. He also received a National Eminence Award from the South India Education Society (SIES), linked to the Kanchi Shankaracharya Math, for contributions to Vedic education, though this stems from an educational body rather than direct state conferral.[1] In popular spheres, Frawley has garnered acclaim among global practitioners of Yoga, Ayurveda, and Vedic astrology as a pioneer in bridging Eastern traditions with Western contexts, founding the American Institute of Vedic Studies in 1988 to offer teachings and consultations.[1] His lectures at Indian spiritual centers and invitations to Dharma-related conferences reflect esteem within Hindu intellectual communities, where he is honored as one of few Western Vedacharyas.[62] This grassroots influence is evident in his authorship of over 40 books, which have cultivated a dedicated following seeking experiential Vedic insights over institutionalized religious frameworks.[63]Academic Criticisms and Responses

Richard Salomon, in his 1989 review published in the Journal of the American Oriental Society, critiqued Frawley's Hymns from the Golden Age: The Rigveda for adopting a "fanciful" interpretive method that disregarded established linguistic evidence on Indo-European languages and Vedic chronology, instead favoring unsubstantiated perpetuation of traditional Vedic narratives over philological rigor. Similarly, scholars have faulted Frawley's historical analyses, such as in The Rig Veda and the History of India (2001), for endorsing the Out of India theory—a claim of Vedic origins exporting Indo-European languages—while minimally addressing counter-evidence from comparative linguistics, which links Sanskrit to steppe pastoralist migrations around 2000–1500 BCE, and archaeology revealing cultural discontinuities in the Indus-Sarasvati region.[64] These critiques portray Frawley's approach as prioritizing ideological advocacy for indigenous continuity and Hindu civilizational primacy over interdisciplinary data integration, lacking peer-reviewed validation typical of academic Indology.[65] Frawley's advocacy for Jyotish (Vedic astrology) as a predictive science intertwined with Ayurveda has drawn dismissal from scientific communities as pseudoscientific, with no replicable empirical mechanisms linking celestial positions to human events or health outcomes, contrasting empirical standards in modern astronomy and medicine. Critics note his background—a bachelor's in psychology rather than specialized training in Sanskrit philology or ancient history—limits his contributions to popular synthesis rather than advancing scholarly debates.[66] In response, Frawley has argued that dominant Indological paradigms stem from colonial-era distortions, Marxist historiography, and secular-materialist biases that undervalue the experiential, yogic, and mantra-based insights of Vedic rishis, which he prioritizes as causal foundations for authentic interpretation. He contends academic gatekeeping excludes practitioner-scholars like himself, enforcing an "apartheid" against Hindu perspectives in Western and Indian academia, and calls for reclaiming history through Indic first-hand sources over imported theories like the Aryan migration model. Frawley maintains his interdisciplinary method—drawing from Ayurveda, yoga, and astronomy—offers practical validity tested over millennia, countering pseudoscience labels by highlighting predictive accuracies in traditional contexts ignored by reductionist science.[67][31]Honors and Legacy

Key Awards

David Frawley received the Padma Bhushan, India's third-highest civilian honor, on January 26, 2015, from President Pranab Mukherjee at Rashtrapati Bhavan for his contributions to Vedic education, yoga, Ayurveda, Jyotish, Vedanta, and promotion of Hindu traditions.[3][1] In December 2015, the South Indian Education Society (SIES) in Mumbai, affiliated with the Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, awarded him the National Eminence Award, recognizing his educational efforts in Vedic knowledge systems; this honor has been conferred on only a select few individuals for exceptional service to India.[68][69] Earlier, in 1994, Frawley was granted the title of Pandit and the Brahmachari Vishwanathji Award in Mumbai for his expertise in Vedic teachings.[62] Frawley has also received honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) degrees from institutions including the University of Natural Health and Svyasa University in Bengaluru, acknowledging his scholarly work in integrative health sciences and Vedic studies.[1]Ongoing Influence and Recent Activities

Frawley maintains an active role as a Vedacharya through the American Institute of Vedic Studies, where he continues to author articles on yogic practices, Vedic astrology, and Hindu dharma, with publications extending into 2025, including "Secrets of Yogic Meditation" on October 16, 2025.[70] He has conducted webinars on topics such as Vedic counseling in August 2025 and Ayurvedic psychology in the same month, emphasizing self-healing and spiritual inquiry rooted in ancient texts.[71] [72] In September 2025, Frawley participated in a live interview on "Yoga Beyond Body and Mind," discussing the integration of yoga with knowledge-based paths like Advaita Vedanta.[73] Earlier that year, on May 23, 2025, he led a webinar on the yogic practice of self-inquiry (Atma-Vichara), drawing from Ramana Maharshi's teachings as a direct path to self-realization.[74] These sessions reflect his ongoing emphasis on experiential spiritual methods over institutional dogma, influencing practitioners in yoga, Ayurveda, and Vedic studies globally.[1] Frawley's influence persists in advocating for Hindu cultural resurgence, as seen in his 2025 articles and commentaries on platforms like Indiafacts, where he addresses contemporary issues such as unity among South Indian Hindus and the broader dharmic response to external critiques.[75] He has also contributed forewords to recent works on raja yoga and tantric practices, reinforcing his foundational role in interpreting Vedic sciences for modern audiences.[2] Through retreats, such as the 2024 Yoga Shakti event celebrated in August 2025 articles, he fosters direct transmission of these traditions, sustaining a network of students and institutions promoting Sanatana Dharma's philosophical and practical dimensions.[76]References

- https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/David_Frawley