Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Digit (unit)

View on Wikipedia

The digit or finger is an ancient and obsolete non-SI unit of measurement of length. It was originally based on the breadth of a human finger.[1] It was a fundamental unit of length in the Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Hebrew, Ancient Greek and Roman systems of measurement.

In astronomy a digit is one twelfth of the diameter of the sun or the moon.[2]

History

[edit]Ancient Egypt

[edit]The digit, also called a finger or fingerbreadth, is a unit of measurement originally based on the breadth of a human finger. In Ancient Egypt it was the basic unit of subdivision of the cubit.[1]

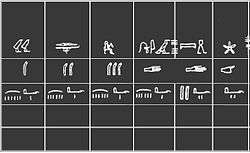

On surviving Ancient Egyptian cubit-rods, the royal cubit is divided into seven palms of four digits or fingers each.[3] The royal cubit measured approximately 525 mm,[4] so the length of the ancient Egyptian digit was about 19 mm.

| Name | Egyptian name | Equivalent Egyptian values | Metric equivalent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal cubit |

|

7 palms or 28 digits | 525 mm | ||||

| Fist | 6 digits | 108 mm | |||||

| Hand | 5 digits | 94 mm | |||||

| Palm |

|

4 digits | 75 mm | ||||

| Digit |

|

1/4 palm | 19 mm |

Mesopotamia

[edit]In the classical Akkadian Empire system instituted in about 2250 BC during the reign of Naram-Sin, the finger was one-thirtieth of a cubit length. The cubit was equivalent to approximately 497 mm, so the finger was equal to about 17 mm. Basic length was used in architecture and field division.

| Unit | Ratio | Metric equivalent |

Sumerian | Akkadian | Cuneiform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grain | 1/180 | 2.8 mm | še | uţţatu | 𒊺 |

| finger | 1/30 | 17 mm | šu-si | ubānu | 𒋗𒋛 |

| foot | 2/3 | 331 mm | šu-du3-a | šīzu | 𒋗𒆕𒀀 |

| cubit | 1 | 497 mm | kuš3 | ammatu | 𒌑 |

Ancient Hebrew system

[edit]Ancient Greece

[edit]Ancient Rome

[edit]Britain

[edit]A digit (lat. digitus, "finger"), when used as a unit of length, is usually a sixteenth of a foot or 3/4" (1.905 cm for the international inch).[6] The width of an adult human male finger tip is indeed about 2 centimetres. In English this unit has mostly fallen out of use, as do others based on the human arm: finger (7/6 digit), palm (4 digits), hand (16/3 digits), shaftment (8 digits), span (12 digits), cubit (24 digits) and ell (60 digits).

Astronomy

[edit]In astronomy a digit is, or was until recently, one twelfth of the diameter of the sun or the moon.[2][7] This is found in the Moralia of Plutarch, XII:23,[8] but the definition as exactly one twelfth of the diameter may be due to Ptolemy. Sosigenes of Alexandria had observed in the 1st century AD that on a dioptra, a disc with a diameter of 11 or 12 digits (of length) was needed to cover the moon.[9]

The unit was used in Arab or Islamic astronomical works such as those of Ṣadr al‐Sharīʿa al‐Thānī (d.1346/7),[10] where it is called Arabic: إصبعا iṣba' , digit or finger.[11]

The astronomical digit was in use in Britain for centuries. Heath, writing in 1760, explains that 12 digits are equal to the diameter in eclipse of the sun, but that 23 may be needed for the Earth's shadow as it eclipses the moon, those over 12 representing the extent to which the Earth's shadow is larger than the Moon.[12] The unit is apparently not in current use, but is found in recent dictionaries.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Hosch, William L. (ed.) (2010) The Britannica Guide to Numbers and Measurement New York, NY: Britannica Educational Publications, 1st edition. ISBN 978-1-61530-108-9, p.203

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 268.

- ^ Selin, Helaine, ed. (1997). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine in non-Western Cultures. Dordrecht: Kluwer. ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9.

- ^ Lepsius, Richard (1865). Die altaegyptische Elle und ihre Eintheilung (in German). Berlin: Dümmler.

- ^ Clagett, Marshall (1999). Ancient Egyptian Science, A Source Book. Volume 3: Ancient Egyptian Mathematics. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-232-0.

- ^ Ronald Edward Zupko (1985). A dictionary of weights and measures for the British Isles: the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. American Philosophical Society. pp. 109–10. ISBN 978-0-87169-168-2. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ a b Macdonald, A.M. (ed.) (1972) Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers ISBN 0-550-10206-X, "digit"

- ^ Plutarchus Chaeronensis, Frank Cole Babbitt (trans.) (1957) Plutarch's Moralia: In fifteen volumes London: William Heinemann, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Volume XII p.144

- ^ Neugebauer, Otto (1975) A History of Ancient Mathematical Astronomy Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-06995-1 Volume 2, p.658

- ^ Hockey, Thomas et al. (eds.) (2007) The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, Springer Reference New York: Springer pp. 1002–1003

- ^ 'Ubayd Allāh ibn Mas'ūd Ṣadr al-S̆arīaẗ al-Aṣġar al-Maḥbūbī, Ahmad S. Dallal (1995) An Islamic response to Greek astronomy: kitāb Ta'dīl hay'at al-aflāk of Ṣadr al-Sharī'a (in Arabic and English) Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-09968-5 p.212

- ^ Heath, Robert (1760). Astronomia accurata; or ... subservient to the three principal Subjects. London: Published by the author. p. ix.