Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Discourse on the Method.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Discourse on the Method

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Discourse on the Method

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

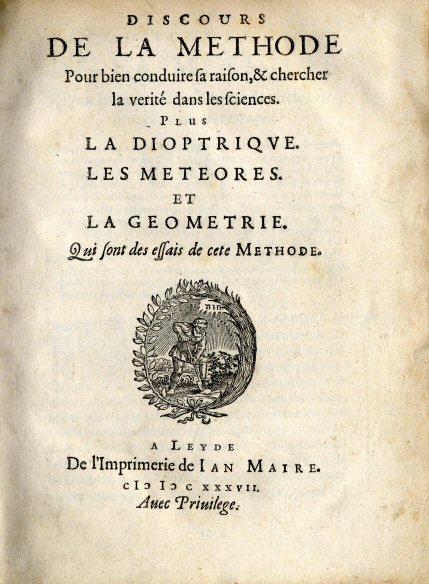

![Title page of Descartes' Discours de la Méthode][float-right]

The Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison et chercher la vérité dans les sciences (Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences) is a short philosophical treatise by René Descartes, first published anonymously in French in 1637 in Leiden, Netherlands.[1][2] In the work, Descartes recounts his dissatisfaction with prevailing scholastic education and proposes a novel method for acquiring reliable knowledge, consisting of four rules: to accept only what is self-evident, to divide problems into manageable parts, to proceed from simple to complex ideas in ordered sequence, and to review comprehensively to ensure nothing is omitted.[3] This method, applied through hyperbolic doubt of all beliefs to reach indubitable foundations, yields the foundational insight cogito ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am"), establishing the certainty of the thinking self and paving the way for proofs of God's existence and the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions.[4] Accompanied by three scientific treatises on optics, meteorology, and geometry demonstrating the method's application, the Discourse served as a provisional introduction to Descartes' more systematic philosophy, marking a pivotal shift toward rationalism and mechanistic science in Western thought by prioritizing innate reason over empirical induction or authority.[5]

In Part IV of the Discourse on the Method (1637), René Descartes concludes his methodical doubt by identifying the foundational certainty: "I am thinking, therefore I exist" (je pense, donc je suis in the original French). [26] This proposition emerges as indubitable because the act of doubting—whether of sensory perceptions, mathematical truths, or the possibility of deception by an evil genius—requires an active thinking entity. [15] Descartes reasons that even if all external reality were illusory, the immediate awareness of one's own thought process affirms the existence of a thinking substance, or res cogitans. [26] This cogito serves as the Archimedean point for rebuilding knowledge, distinct from scholastic reliance on authority or senses. [17] Descartes emphasizes that the certainty derives not from logical deduction but from intuitive self-evidence: the proposition is grasped directly upon reflection, resisting hyperbolic skepticism. [27] He extends this to other self-evident truths perceived with equal clarity and distinctness, such as simple mathematical ideas (e.g., that a triangle's internal angles sum to two right angles) or the innate concept of a perfect being. [17] These are "simple natures" known per se, without need for further proof, forming the building blocks of demonstrative reasoning. [17] Building on the cogito, Descartes argues for the existence of God as another self-evident truth, inferred from the clear and distinct idea of a non-deceiving supreme being implanted in the mind. [15] This guarantees the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions generally, as a truthful God would not permit systematic error in such intuitions. [26] Unlike contingent empirical claims, these truths hold independently of sensory verification, privileging intellectual intuition over probabilistic assent. [27] Critics later noted potential circularity in invoking God to validate clarity, but Descartes maintains the cogito and basic intuitions as immediately certain, prior to theological proofs. [26]

Historical Context

Publication Details and Anonymity

The Discours de la méthode pour bien conduire sa raison, et chercher la vérité dans les sciences was first published in 1637 by the Leiden printer Jan Maire in the Dutch Republic.[6] [7] The edition comprised the principal discourse along with three appended scientific essays—La Dioptrique, Les Météores, and La Géométrie—intended to exemplify the proposed method in optics, meteorology, and geometry, respectively.[8] Unlike most philosophical works of the era, it was composed in French to reach a broader readership beyond Latin-literate scholars.[9] The initial printing appeared anonymously, omitting the author's name from the title page despite the text's extensive autobiographical elements recounting the author's intellectual journey.[9] [10] This choice reflected Descartes' prudence amid theological sensitivities, particularly after the 1633 condemnation of Galileo by the Roman Inquisition, which led him to suppress an earlier manuscript on physics and cosmology that endorsed heliocentrism.[11] Anonymity allowed the arguments to stand on their intrinsic merit, detached from personal authority, while mitigating risks of ecclesiastical censure for the work's rationalist and mechanistic implications.[12] Descartes' authorship soon circulated among intellectuals, and later editions from 1644 onward, including a Latin translation in 1644 and French reprints in Paris, bore his name explicitly.[9] The anonymous debut thus served as a strategic prelude to his more openly attributed philosophical publications, such as the Meditations on First Philosophy in 1641.[13]Intellectual and Personal Background

René Descartes was born on March 31, 1596, in La Haye en Touraine, France, to Joachim Descartes, a lawyer and councillor in the Parlement of Brittany, and Jeanne Brochard, who died shortly after his birth.[14] Raised primarily by his maternal grandmother in a family of modest bourgeois professionals including doctors and lawyers, Descartes was the youngest of three surviving children and suffered from fragile health in childhood, which contributed to a lifelong emphasis on methodical care for the body.[15] Upon his father's death in 1617, he inherited sufficient property to secure financial independence, allowing him to forgo a legal career and pursue independent intellectual inquiry without reliance on patronage or employment.[14] Descartes received his early education at the Jesuit Collège de La Flèche from 1606 or 1607 to 1614, one of Europe's premier institutions, where he studied the humanities, Aristotelian scholastic philosophy, logic, physics, metaphysics, and mathematics based on texts by Christopher Clavius.[16] While acknowledging the rigor of this training, he later critiqued scholastic methods for their reliance on unexamined authorities and verbal subtleties over clear evidence, finding value primarily in mathematics for its demonstrative certainty.[14] He briefly studied law at the University of Poitiers, earning a baccalauréat and licence by 1616 to satisfy familial expectations, but abandoned practice of the profession.[16] In 1618, Descartes enlisted as a gentleman volunteer in the Dutch States Army under Protestant Prince Maurice of Nassau at Breda, where he encountered the physician and mathematician Isaac Beeckman, who reignited his interest in applying mathematical reasoning to physical problems such as music, mechanics, and gravity.[16] This collaboration marked a pivotal shift toward seeking a universal method grounded in mathematical deduction rather than sensory observation or tradition.[15] Departing military service in 1619, he traveled through Europe, joining the Bavarian army under Maximilian I; during winter quarters in Ulm, on November 10, 1619, he experienced three vivid dreams in a stove-heated room, interpreting them as a divine call to found a new science unifying all knowledge through indubitable principles.[14] From 1620 to 1628, Descartes undertook extensive travels across Bohemia, Hungary, Italy (including visits to Rome and Venice in 1623–1625), France, and Switzerland, engaging sporadically with intellectuals like Marin Mersenne while refining his ideas amid exposure to diverse cultures and the limits of existing philosophies.[16] Influenced by Renaissance skepticism—evident in figures like Michel de Montaigne—and the recent revival of ancient atomism, he sought to counter radical doubt not by rejecting it but by employing it methodically to establish self-evident truths, drawing on mathematical models for philosophical rigor.[14] In 1628, he settled in the Netherlands, attracted by its relative tolerance, political stability, and opportunities for anonymity, which enabled uninterrupted work on treatises like The World (suppressed after Galileo's 1633 condemnation) and culminated in the 1637 Discourse on the Method as a provisional autobiographical sketch of his intellectual path.[14]Structure and Content

Part I: Examination of Existing Sciences

In Part I of Discourse on the Method, René Descartes provides an autobiographical account of his early education and experiences, using them to evaluate the reliability of established sciences and disciplines. He describes attending the Jesuit college at La Flèche from approximately 1606 to 1614, where he received instruction in languages, ancient literature, history, rhetoric, and logic.[17] While acknowledging the value of these studies for broadening the mind and fostering eloquence, Descartes argues they prioritize verbal facility over genuine knowledge, offering little certainty or utility for discovering truth.[18] He critiques logic specifically for its proliferation of rules that, rather than clarifying thought, obscure it through excessive precepts derived from prior errors, rendering the system ineffective for advancing understanding.[17] Mathematics stands out in Descartes' assessment as the sole discipline providing evident demonstrations and absolute certainty, akin to constructing evident sequences where each step follows necessarily from the prior.[18] However, he laments its limited application beyond abstract problems, noting that even in geometry and arithmetic, practitioners failed to extend its rigor to broader inquiries. In contrast, moral philosophy appeared plausible but lacked demonstrative force, while medicine, law, and theology—rooted in scholastic traditions—yielded only probable opinions marred by controversy and dependence on unexamined authorities like Aristotle.[17] Descartes observes that scholastic philosophy, despite promising wisdom through its vast tomes, devolves into endless disputes over minutiae, as its methods rely on sensory reports and ancient texts without independent verification, fostering doubt rather than resolution.[15] Following his formal education, Descartes recounts enlisting in military service around 1618 and traveling across Europe from 1619 to 1620, encountering diverse customs, laws, and beliefs that underscored the relativity of human judgments.[17] These observations led him to question the reliability of both scholarly traditions and popular opinions, as even the most esteemed experts disagreed fundamentally, suggesting that no single science or culture held uncontested truth. He reflects that while common sense often outperforms book learning in practical matters, it too falters without a systematic approach, as evidenced by the variability in judgments among equally rational individuals.[18] Ultimately, Descartes concludes from this examination that existing sciences fail to provide a secure foundation for knowledge, with mathematics offering the nearest model of certainty but requiring reform to address real-world complexities.[17] This dissatisfaction prompts his resolve to dismantle inherited beliefs through methodical doubt, akin to an architect razing unstable structures to rebuild on firm ground, prioritizing individual reason over collective authority or tradition.[18] He emphasizes that true progress demands starting anew, free from the prejudices accumulated in youth, to seek self-evident principles capable of yielding indubitable results across disciplines.[15]Part II: Formulation of the Method

![Portrait of René Descartes][float-right] Part II of Discourse on the Method details René Descartes' formulation of a methodical approach to knowledge acquisition, developed during his travels in Germany amid the disruptions of the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648).[19] In solitude, Descartes reflected on the value of unified intellectual direction, analogizing it to architecture where a single designer's plan surpasses piecemeal efforts, as seen in irregular ancient cities versus planned modern ones like those in Europe.[19] He resolved to dismantle prior beliefs, akin to demolishing a faulty building, and rebuild on secure foundations, drawing lessons from logic's syllogisms (useful for confirmation but not discovery), geometry and algebra's evident demonstrations, and the need to reform scholastic methods.[19] This led to four fundamental precepts, distilled from his earlier, more elaborate Rules for the Direction of the Mind (composed around 1628 but unpublished during his lifetime).[17] These rules emphasize clarity, analysis, synthesis, and completeness:- Accept nothing as true unless it presents itself clearly and distinctly to the mind, excluding all doubt to prevent prejudice and hasty judgments.[19][17]

- Divide each difficulty into the maximum number of parts required for adequate resolution.[19][17]

- Order thoughts progressively from the simplest and most comprehensible objects to the more complex, imposing sequence even where natural order is absent.[19][17]

- Conduct enumerations and general reviews so thoroughly as to ensure no element is overlooked.[19][17]

Part III: Provisional Moral Code

In Part III of Discourse on the Method, published in 1637, Descartes addresses the practical challenge of conducting one's life amid systematic doubt, proposing a temporary ethical framework to ensure stability and prevent indecision from paralyzing action. Recognizing that demolishing prior beliefs without immediate replacements could lead to moral anarchy, he devises a "provisional moral code" (morale par provision) comprising three or four maxims derived from natural reason, intended solely as interim guidance until metaphysical certainties are established. This code prioritizes conformity to established norms, personal resolve, self-mastery, and intellectual pursuit, reflecting Descartes' aim to balance skepticism with everyday functionality.[20][18] The first maxim instructs adherence to the laws and customs of one's country, the prevailing religion (in Descartes' case, Catholicism), and the most moderate and least extreme opinions commonly held by prudent individuals. Descartes justifies this by analogy to a traveler who follows local paths to avoid getting lost, arguing that such conformity provides a reliable, if imperfect, basis for conduct when certainty is absent; he explicitly avoids rash innovation in religion or state matters, having observed the harms of reformist zeal. This rule underscores a conservative pragmatism, favoring social order over speculative upheaval.[20][21][18] The second maxim emphasizes firmness and resolution in executing decisions, once formed after sufficient deliberation, even if they prove erroneous. Descartes compares this to the resolve needed in games of chance or war, where hesitation invites defeat; he draws from personal experience of past indecisiveness, positing that consistent action, guided by the best available judgment, yields better outcomes than perpetual vacillation. This promotes a Stoic-like determination, valuing the exercise of will over infallible foresight.[20][18] The third maxim, sometimes subdivided into a fourth, focuses on mastering one's desires by willing only what lies within one's control, thereby achieving contentment regardless of fortune's vicissitudes. Descartes advocates restricting ambitions to attainable goods—such as health, knowledge, and virtue—rather than pursuing elusive externals like wealth or honor, which breed dissatisfaction; he illustrates this with the observation that true felicity stems from internal disposition, not external success. In reviewing human occupations, he concludes that the most conducive to happiness is philosophical inquiry into truth via methodical doubt and demonstration, as it aligns with human reason's highest capacity and yields enduring satisfaction over transient pleasures or vanities.[20][21][18] This provisional code, while not Descartes' final ethical system—later elaborated in works like The Passions of the Soul (1649)—serves as a bridge between radical epistemology and practical life, embodying his view that ethics must await foundational metaphysics yet cannot be indefinitely suspended. Scholars note its ambiguity in numbering (three versus four maxims), stemming from Descartes' fluid presentation, but affirm its role in enabling solitary reflection amid worldly duties.[20][21]Part IV: Foundations of Certain Knowledge

In Part IV of Discourse on the Method, published in 1637, Descartes details his initial meditations aimed at establishing an unshakeable foundation for knowledge by systematically doubting all beliefs susceptible to error. He begins by withholding assent from any proposition where doubt is possible, including sensory data prone to deception and even demonstrative sciences like mathematics, which he hypothetically undermines through the conceit of a malicious demon capable of falsifying all perceptions and thoughts.[22][23] Amid this universal doubt, Descartes identifies a self-evident truth: the very act of doubting presupposes thinking, yielding the indubitable principle "Cogito, ergo sum"—"I think, therefore I am." This foundation resists skepticism because any effort to deny it affirms the existence of a thinking subject; thus, the thinker exists as a res cogitans, a substance defined by thought alone, independent of the body or material extension.[22][23] Building on this certainty, Descartes examines the idea of a perfect being—God—innate within him despite his own imperfections, inferring that such an idea could only derive from a supremely perfect cause, thereby proving God's existence through a causal argument analogous to geometric proofs.[22] He further contends that God's perfection precludes deception, ensuring the reliability of clear and distinct ideas perceived by the natural light of reason, such as the distinction between mind and body.[23] These elements—the cogito as primal certainty, the mind's nature, divine existence, and the trustworthiness of rational intuition—form the bedrock for certain knowledge, allowing Descartes to reconstruct science and philosophy without reliance on uncertain traditions or senses.[22][23]Part V: Order of Philosophical Inquiry

In Part V of Discourse on the Method, René Descartes delineates the systematic progression of inquiry from metaphysical certainties to the principles of physics, emphasizing deduction from indubitable foundations to avoid reliance on sensory uncertainty or scholastic traditions. Having established in prior parts the existence of the self as a thinking substance and a non-deceiving God, Descartes proceeds to demonstrate the real distinction between the mind (res cogitans) and body (res extensa), arguing that this separation provides grounds for the soul's incorruptibility. He then applies the same method to corporeal nature, treating matter as pure extension and deriving universal laws from divine immutability, thereby constructing a mechanistic account of the universe.[19][5] The order begins with metaphysical proofs to secure the foundations: Descartes claims to possess demonstrations that the soul differs from the body and can subsist without it, rendering the soul naturally incorruptible by virtue of lacking extension or parts subject to decay. This distinction rests on the clear and distinct perception of the mind as a substance "whose whole essence or nature consists only in thinking" and the body as divisible extended matter, with God's existence ensuring that such perceptions correspond to reality.[24] Without this priority of metaphysics, physical inquiries risk error, as sensory data alone cannot yield certainty; instead, Descartes deduces the attributes of matter—figure, magnitude, and motion—from the concept of extension, independent of empirical induction.[19] Transitioning to physics, Descartes identifies three primitive laws of nature, inferred from God's perfection and immutability as the primary cause. The first law states that each portion of matter remains in its state of rest or uniform motion unless altered by external causes, reflecting divine conservation of motion at every instant of creation. The second posits that when bodies move, they tend toward straight lines, deviating only by collision. The third concerns impacts, specifying how motion transfers proportionally to masses and velocities, akin to elastic collisions, enabling explanations of planetary vortices, elemental formation, and terrestrial phenomena without invoking occult qualities or final causes.[19][5] He illustrates this by deriving the structure of the heavens, stars, and earth from these principles, positing a plenum devoid of vacuum where matter circulates in fluid eddies. Descartes applies this framework to the human body, portraying it as an intricate machine fabricated by God, with vital functions like digestion, nutrition, respiration, and circulation arising mechanically from material dispositions rather than immaterial influences. He describes the heart as a source of innate heat that rarifies blood, propelling it through vessels to sustain life, a process observable in animals and independent of thought. To distinguish human cognition, he invokes the criterion of articulate speech and reasoned response, which automata or beasts—lacking reason and acting solely by organ configuration—cannot replicate, even if engineered to mimic external behaviors. Thus, the rational soul, residing as the principle of thought, elevates humans above mere mechanisms.[24][5] This mechanistic physiology reinforces the soul's immortality: as an unextended, indivisible thinking substance, the soul lacks the corruptible parts inherent to bodies and admits no observable cause of destruction, unlike material forms subject to dissolution. Descartes withheld full publication of his physical treatise Le Monde following Galileo's 1633 condemnation by the Inquisition for heliocentrism, opting instead to summarize its contents hypothetically as truths for a divinely created world. He alludes to appended essays on Dioptrics, Meteors, and Geometry as exemplars of applying the method to optics, cosmology, and mathematics, respectively, while prioritizing further metaphysical refinement.[19][24]Part VI: Imperatives for Scientific Progress

In Part VI, Descartes elaborates on the transformative potential of his method for scientific advancement, asserting that its application to medicine could yield remedies surpassing empirical trial-and-error approaches, while in mechanics it promises inventions enabling humanity to harness natural forces for sustenance and health preservation. He envisions philosophy not as abstract speculation but as a systematic edifice—rooted in the metaphysical certainties of Parts I–IV—yielding practical mastery over nature, where knowledge progresses deductively from first principles, confirmed by controlled experiments rather than probabilistic conjectures or authoritative dogmas. This framework prioritizes utility: sciences should target human flourishing, such as eradicating diseases through mechanistic explanations of bodily functions, over idle controversies.[25][19] A pivotal imperative emerges from Descartes' circumspection regarding publication: scientific claims must rest on self-evident truths accessible via reason, eschewing unverified hypotheses vulnerable to empirical refutation or institutional censure. He describes suppressing his treatise The World—a detailed cosmogony positing a vortex-based solar system with a non-geocentric Earth—upon learning of the Inquisition's 1633 proceedings against Galileo, whose Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (1632) precipitated condemnation for heliocentric advocacy without conclusive proof against scriptural geocentrism. Descartes resolves to advance only indemonstrable-by-reason propositions, insisting that genuine physics, derived from God's immutability and clear ideas, harmonizes with theology; scripture addresses salvation, not natural mechanisms, and apparent conflicts arise from misinterpretation or incomplete knowledge. This demands provisional restraint in disseminating unproven theories, favoring incremental disclosure of method and select proofs to foster progress without provoking doctrinal strife.[19][17] Progress further requires integrating deduction with empirical rigor, as pure reasoning alone suffices for simple truths but complex phenomena—such as atmospheric or physiological processes—demand collaborative experimentation to amass data beyond solitary means. Descartes proposes that affluent patrons or learned societies fund systematic trials to validate hypotheses, yet underscores individual responsibility: judgments must stem from personal discernment of clear and distinct ideas, not deference to majority opinion or precedent, lest error propagate as in scholasticism. He likens scientific enrichment to commerce, where initial modest gains compound through methodical reinvestment, urging dissemination of reliable foundations to accelerate collective discovery while guarding against hasty generalizations. These directives—firm epistemic groundwork, hypothesis-testing via experiment, prioritization of beneficial applications, and judicious navigation of authority—constitute Descartes' blueprint for supplanting stagnant traditions with a dynamic, evidence-aligned pursuit of truth.[25][19]Core Concepts

Methodical Doubt and Hyperbolic Skepticism

Methodical doubt, as Descartes delineates it in Part IV of the Discourse on the Method, entails a deliberate and systematic rejection of all beliefs admitting even the remotest possibility of falsity, with the aim of excavating secure epistemic foundations from which certain knowledge may be erected. He declares his intent to regard as "absolutely false all opinions in regard to which I could suppose the least ground for doubt," thereby employing doubt not as an end but as a provisional tool to dismantle provisional credences.[19] This procedure presupposes no prior commitment to skepticism's ultimate validity but leverages it to isolate indubitable residues amid potential deceptions.[26] The initial target of this scrutiny comprises sensory evidence, which Descartes impugns due to documented instances of perceptual error, such as mirages or misjudged distances. He reasons that "it is sometimes proved to me that these senses are deceptive, and it is wiser not to trust entirely to any thing by which we have once been deceived," extending this caution universally to preclude reliance on empirical inputs without corroboration.[19] Building upon this, Descartes invokes the dream hypothesis to erode distinctions between veridical and illusory states: "How often has it happened to me that in the night I dreamt that I found myself in this particular place, that I was dressed and seated near the fire, whilst in reality I was lying undressed in bed!" Such reflections imply that present sensations, lacking intrinsic markers of authenticity, might equally constitute fabrications, thereby casting wholesale doubt on the external world's independent existence.[19] Hyperbolic skepticism amplifies this process through the supposition of a supremely potent and deceitful entity—termed a "malicious demon"—who deploys exhaustive wiles to ensnare judgment, compelling reconsideration of even axiomatic truths like arithmetic or geometry. Under this scenario, Descartes entertains that "the heavens, the earth, colors, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgment," rendering no proposition immune save those impervious to such maximal subversion.[19] This exaggerated maneuver, while concededly extravagant, exhaustively probes epistemic vulnerabilities to affirm only what withstands universal undermining.[26] Unlike indiscriminate skepticism, Descartes' variant remains methodical and provisional, oriented toward reconstruction rather than perpetual suspension, as evidenced by its integration within a broader architectonic of inquiry that progresses from doubt to affirmation upon discovering self-evident anchors.[26]Cogito Ergo Sum and Self-Evident Truths

In Part IV of the Discourse on the Method (1637), René Descartes concludes his methodical doubt by identifying the foundational certainty: "I am thinking, therefore I exist" (je pense, donc je suis in the original French). [26] This proposition emerges as indubitable because the act of doubting—whether of sensory perceptions, mathematical truths, or the possibility of deception by an evil genius—requires an active thinking entity. [15] Descartes reasons that even if all external reality were illusory, the immediate awareness of one's own thought process affirms the existence of a thinking substance, or res cogitans. [26] This cogito serves as the Archimedean point for rebuilding knowledge, distinct from scholastic reliance on authority or senses. [17] Descartes emphasizes that the certainty derives not from logical deduction but from intuitive self-evidence: the proposition is grasped directly upon reflection, resisting hyperbolic skepticism. [27] He extends this to other self-evident truths perceived with equal clarity and distinctness, such as simple mathematical ideas (e.g., that a triangle's internal angles sum to two right angles) or the innate concept of a perfect being. [17] These are "simple natures" known per se, without need for further proof, forming the building blocks of demonstrative reasoning. [17] Building on the cogito, Descartes argues for the existence of God as another self-evident truth, inferred from the clear and distinct idea of a non-deceiving supreme being implanted in the mind. [15] This guarantees the reliability of clear and distinct perceptions generally, as a truthful God would not permit systematic error in such intuitions. [26] Unlike contingent empirical claims, these truths hold independently of sensory verification, privileging intellectual intuition over probabilistic assent. [27] Critics later noted potential circularity in invoking God to validate clarity, but Descartes maintains the cogito and basic intuitions as immediately certain, prior to theological proofs. [26]