Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Critique of Pure Reason

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Part of a series on |

| Immanuel Kant |

|---|

|

|

Category • |

The Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to decide on "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics".

Kant builds on the work of empiricist philosophers such as John Locke and David Hume, as well as rationalist philosophers such as René Descartes, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff. He expounds new ideas on the nature of space and time, and tries to provide solutions to the skepticism of Hume regarding knowledge of the relation of cause and effect and that of René Descartes regarding knowledge of the external world. This is argued through the transcendental idealism of objects (as appearance) and their form of appearance. Kant regards the former "as mere representations and not as things in themselves", and the latter as "only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves". This grants the possibility of a priori knowledge, since objects as appearance "must conform to our cognition...which is to establish something about objects before they are given to us." Knowledge independent of experience Kant calls "a priori" knowledge, while knowledge obtained through experience is termed "a posteriori".[3] According to Kant, a proposition is a priori if it is necessary and universal. A proposition is necessary if it is not false in any case and so cannot be rejected; rejection is contradiction. A proposition is universal if it is true in all cases, and so does not admit of any exceptions. Knowledge gained a posteriori through the senses, Kant argues, never imparts absolute necessity and universality, because it is possible that we might encounter an exception.[4]

Kant further elaborates on the distinction between "analytic" and "synthetic" judgments.[5] A proposition is analytic if the content of the predicate-concept of the proposition is already contained within the subject-concept of that proposition.[6] For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are extended" analytic, since the predicate-concept ('extended') is already contained within—or "thought in"—the subject-concept of the sentence ('body'). The distinctive character of analytic judgments was therefore that they can be known to be true simply by an analysis of the concepts contained in them; they are true by definition. In synthetic propositions, on the other hand, the predicate-concept is not already contained within the subject-concept. For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are heavy" synthetic, since the concept 'body' does not already contain within it the concept 'weight'.[7] Synthetic judgments therefore add something to a concept, whereas analytic judgments only explain what is already contained in the concept.

Before Kant, philosophers held that all a priori knowledge must be analytic. Kant, however, argues that our knowledge of mathematics, of the first principles of natural science, and of metaphysics, is both a priori and synthetic. The peculiar nature of this knowledge cries out for explanation. The central problem of the Critique is therefore to answer the question: "How are synthetic a priori judgments possible?"[8] It is a "matter of life and death" to metaphysics and to human reason, Kant argues, that the grounds of this kind of knowledge be explained.[8]

Though it received little attention when it was first published, the Critique later attracted attacks from both empiricist and rationalist critics, and became a source of controversy. It has exerted an enduring influence on Western philosophy, and helped bring about the development of German idealism. The book is considered a culmination of several centuries of early modern philosophy and an inauguration of late modern philosophy.

Background

[edit]Early rationalism

[edit]Before Kant, it was generally held that truths of reason must be analytic, meaning that what is stated in the predicate must already be present in the subject (e.g., "An intelligent man is intelligent" or "An intelligent man is a man").[9] In either case, the judgment is analytic because it is ascertained by analyzing the subject. It was thought that all truths of reason, or necessary truths, are of this kind: that in all of them there is a predicate that is only part of the subject of which it is asserted.[9] If this were so, attempting to deny anything that could be known a priori (e.g., "An intelligent man is not intelligent" or "An intelligent man is not a man") would involve a contradiction. It was therefore thought that the law of contradiction is sufficient to establish all a priori knowledge.[10]

David Hume at first accepted the general view of rationalism about a priori knowledge. However, upon closer examination of the subject, Hume discovered that some judgments thought to be analytic, especially those related to cause and effect, were actually synthetic (i.e., no analysis of the subject will reveal the predicate). They thus depend exclusively upon experience and are therefore a posteriori.

Kant's rejection of Hume's empiricism

[edit]Before Hume, rationalists had held that effect could be deduced from cause; Hume argued that it could not and from this inferred that nothing at all could be known a priori in relation to cause and effect. Kant, who was brought up under the auspices of rationalism, was deeply impressed by Hume's skepticism. "I freely admit that it was the remembrance of David Hume which, many years ago, first interrupted my dogmatic slumber and gave my investigations in the field of speculative philosophy a completely different direction."[11]

Kant decided to find an answer and spent at least twelve years thinking about the subject.[12] Although the Critique of Pure Reason was set down in written form in just four to five months, while Kant was also lecturing and teaching, the work is a summation of the development of Kant's philosophy throughout those twelve years.[13]

Kant's work was stimulated by his decision to take seriously Hume's skeptical conclusions about such basic principles as cause and effect, which had implications for Kant's grounding in rationalism. In Kant's view, Hume's skepticism rested on the premise that all ideas are presentations of sensory experience. The problem that Hume identified was that basic principles such as causality cannot be derived from sense experience only: experience shows only that one event regularly succeeds another, not that it is caused by it.

In section VI ("The General Problem of Pure Reason") of the introduction to the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant explains that Hume stopped short of considering that a synthetic judgment could be made 'a priori'. Kant's goal was to find some way to derive cause and effect without relying on empirical knowledge. Kant rejects analytical methods for this, arguing that analytic reasoning cannot tell us anything that is not already self-evident, so his goal was to find a way to demonstrate how the synthetic a priori is possible.

To accomplish this goal, Kant argued that it would be necessary to use synthetic reasoning. However, this posed a new problem: how is it possible to have synthetic knowledge that is not based on empirical observation; that is, how are synthetic a priori truths possible? This question is exceedingly important, Kant maintains, because he contends that all important metaphysical knowledge is of synthetic a priori propositions. If it is impossible to determine which synthetic a priori propositions are true, he argues, then metaphysics as a discipline is impossible.

Synthetic a priori judgments

[edit]

Kant argues that there are synthetic judgments such as the connection of cause and effect (e.g., "... Every effect has a cause.") where no analysis of the subject will produce the predicate. Kant reasons that statements such as those found in geometry and Newtonian physics are synthetic judgments. Kant uses the classical example of 7 + 5 = 12. No amount of analysis will find 12 in either 7 or 5 and vice versa, since an infinite number of two numbers exist that will give the sum 12. Thus Kant concludes that all pure mathematics is synthetic though a priori; the number 7 is seven and the number 5 is five and the number 12 is twelve and the same principle applies to other numerals; in other words, they are universal and necessary. For Kant then, mathematics is synthetic judgment a priori. Conventional reasoning would have regarded such an equation to be analytic a priori by considering both 7 and 5 to be part of one subject being analyzed, however Kant looked upon 7 and 5 as two separate values, with the value of five being applied to that of 7 and synthetically arriving at the logical conclusion that they equal 12. This conclusion led Kant into a new problem as he wanted to establish how this could be possible: How is pure mathematics possible?[12] This also led him to inquire whether it could be possible to ground synthetic a priori knowledge for a study of metaphysics, because most of the principles of metaphysics from Plato through to Kant's immediate predecessors made assertions about the world or about God or about the soul that were not self-evident but which could not be derived from empirical observation (B18-24). For Kant, all post-Cartesian metaphysics is mistaken from its very beginning: the empiricists are mistaken because they assert that it is not possible to go beyond experience and the dogmatists are mistaken because they assert that it is possible to go beyond experience through theoretical reason.

Therefore, Kant proposes a new basis for a science of metaphysics, posing the question: how is a science of metaphysics possible, if at all? According to Kant, only practical reason, the faculty of moral consciousness, the moral law of which everyone is immediately aware, makes it possible to know things as they are.[14] This led to his most influential contribution to metaphysics: the abandonment of the quest to try to know the world as it is "in itself" independent of sense experience. He demonstrated this with a thought experiment, showing that it is not possible to meaningfully conceive of an object that exists outside of time and has no spatial components and is not structured following the categories of the understanding (Verstand), such as substance and causality. Although such an object cannot be conceived, Kant argues, there is no way of showing that such an object does not exist. Therefore, Kant says, the science of metaphysics must not attempt to reach beyond the limits of possible experience but must discuss only those limits, thus furthering the understanding of ourselves as thinking beings. The human mind is incapable of going beyond experience so as to obtain a knowledge of ultimate reality, because no direct advance can be made from pure ideas to objective existence.[15]

Kant writes: "Since, then, the receptivity of the subject, its capacity to be affected by objects, must necessarily precede all intuitions of these objects, it can readily be understood how the form of all appearances can be given prior to all actual perceptions, and so exist in the mind a priori" (A26/B42). Appearance is then, via the faculty of transcendental imagination (Einbildungskraft), grounded systematically in accordance with the categories of the understanding. Kant's metaphysical system, which focuses on the operations of cognitive faculties (Erkenntnisvermögen), places substantial limits on knowledge not found in the forms of sensibility (Sinnlichkeit). Thus it sees the error of metaphysical systems prior to the Critique as failing to first take into consideration the limitations of the human capacity for knowledge. Transcendental imagination is described in the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason but Kant omits it from the second edition of 1787.[16]

It is because he takes into account the role of people's cognitive faculties in structuring the known and knowable world that in the second preface to the Critique of Pure Reason Kant compares his critical philosophy to Copernicus' revolution in astronomy. Kant (Bxvi) writes:

Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects. But all attempts to extend our knowledge of objects by establishing something in regard to them a priori, by means of concepts, have, on this assumption, ended in failure. We must therefore make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge.

Kant's view is that in explaining the movement of celestial bodies, Copernicus rejected the idea that the movement is only in the stars in order to allow that such movement is also due to the motion of ourselves as spectators. Thus, the Copernican revolution in astronomy shifted our understanding of the universe from one that is geocentric, without reference to the motion of ourselves as spectators, to one that is heliocentric with reference to the motion of ourselves as spectators. Likewise, Kant aims to shift metaphysics from one that requires our understanding to conform to the nature of objects to one that requires the objects of experience to conform to the necessary conditions of our knowledge. Consequently, knowledge does not depend solely on the object of knowledge but also on the capacity of the knower.[17]

Transcendental idealism

[edit]Kant's transcendental idealism should be distinguished from idealistic systems such as that of George Berkeley which deny all claims of extramental existence and consequently turn phenomenal objects into things-in-themselves. While Kant claimed that phenomena depend upon the conditions of sensibility, space and time, and on the synthesizing activity of the mind manifested in the rule-based structuring of perceptions into a world of objects, this thesis is not equivalent to mind-dependence in the sense of Berkeley's idealism. Kant defines transcendental idealism:

I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrine that they are all together to be regarded as mere representations and not things in themselves, and accordingly that time and space are only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves. To this idealism is opposed transcendental realism, which regards space and time as something given in themselves (independent of our sensibility).

— Critique of Pure Reason, A369

Kant's approach

[edit]In Kant's view, a priori intuitions and concepts provide some a priori knowledge, which also provides the framework for a posteriori knowledge. Kant also believed that causality is a conceptual organizing principle imposed upon nature, albeit nature understood as the sum of appearances that can be synthesized according to a priori concepts.

In other words, space and time are a form of perceiving and causality is a form of knowing. Both space and time and conceptual principles and processes pre-structure experience.

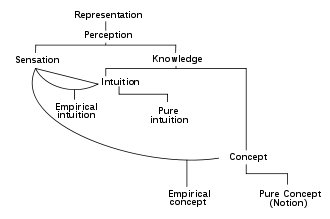

Things as they are "in themselves"—the thing in itself, or das Ding an sich—are unknowable. For something to become an object of knowledge, it must be experienced, and experience is structured by the mind—both space and time being the forms of intuition (Anschauung; for Kant, intuition is the process of sensing or the act of having a sensation)[18] or perception, and the unifying, structuring activity of concepts. These aspects of mind turn things-in-themselves into the world of experience. There is never passive observation or knowledge.

According to Kant, the transcendental ego—the "Transcendental Unity of Apperception"—is similarly unknowable. Kant contrasts the transcendental ego to the empirical ego, the active individual self subject to immediate introspection. One is aware that there is an "I," a subject or self that accompanies one's experience and consciousness. Since one experiences it as it manifests itself in time, which Kant proposes is a subjective form of perception, one can know it only indirectly: as object, rather than subject. It is the empirical ego that distinguishes one person from another providing each with a definite character.[19]

Contents

[edit]The Critique of Pure Reason is arranged around several basic distinctions. After the two Prefaces (the A edition Preface of 1781 and the B edition Preface of 1787) and the Introduction, the book is divided into the Doctrine of Elements and the Doctrine of Method.

Doctrine of Elements and of Method

[edit]The Doctrine of Elements sets out the a priori products of the mind, and the correct and incorrect use of these presentations. Kant further divides the Doctrine of Elements into the Transcendental Aesthetic and the Transcendental Logic, reflecting his basic distinction between sensibility and the understanding. In the "Transcendental Aesthetic" he argues that space and time are pure forms of intuition inherent in our faculty of sense. The "Transcendental Logic" is separated into the Transcendental Analytic and the Transcendental Dialectic:

- The Transcendental Analytic sets forth the appropriate uses of a priori concepts, called the categories, and other principles of the understanding, as conditions of the possibility of a science of metaphysics. The section titled the "Metaphysical Deduction" considers the origin of the categories. In the "Transcendental Deduction", Kant then shows the application of the categories to experience. Next, the "Analytic of Principles" sets out arguments for the relation of the categories to metaphysical principles. This section begins with the "Schematism", which describes how the imagination can apply pure concepts to the object given in sense perception. Next are arguments relating the a priori principles with the schematized categories.

- The Transcendental Dialectic describes the transcendental illusion behind the misuse of these principles in attempts to apply them to realms beyond sense experience. Kant’s most significant arguments are the "Paralogisms of Pure Reason", the "Antinomy of Pure Reason", and the "Ideal of Pure Reason", aimed against, respectively, traditional theories of the soul, the universe as a whole, and the existence of God. In the Appendix to the "Critique of Speculative Theology" Kant describes the role of the transcendental ideas of reason.

The Doctrine of Method contains four sections. The first section, "Discipline of Pure Reason", compares mathematical and logical methods of proof, and the second section, "Canon of Pure Reason", distinguishes theoretical from practical reason.

The divisions of the Critique of Pure Reason

[edit]Dedication

- 1. First and second Prefaces

- 2. Introduction

- 3. Transcendental Doctrine of Elements

- A. Transcendental Aesthetic

- (1) On space

- (2) On time

- B. Transcendental Logic

- (1) Transcendental Analytic

- a. Analytic of Concepts

- i. Metaphysical Deduction

- ii. Transcendental Deduction

- b. Analytic of Principles

- i. Schematism (bridging chapter)

- ii. System of Principles of Pure Understanding

- a. Axioms of Intuition

- b. Anticipations of Perception

- c. Analogies of Experience

- d. Postulates of Empirical Thought (Refutation of Idealism)

- iii. Ground of Distinction of Objects into Phenomena and Noumena

- iv. Appendix on the Amphiboly of the Concepts of Reflection

- a. Analytic of Concepts

- (2) Transcendental Dialectic: Transcendental Illusion

- a. Paralogisms of Pure Reason

- b. Antinomy of Pure Reason

- c. Ideal of Pure Reason

- d. Appendix to Critique of Speculative Theology

- (1) Transcendental Analytic

- A. Transcendental Aesthetic

- 4. Transcendental Doctrine of Method

- A. Discipline of Pure Reason

- B. Canon of Pure Reason

- C. Architectonic of Pure Reason

- D. History of Pure Reason

Table of contents

[edit]| Critique of Pure Reason[20] | |||||||||||||||

| Transcendental Doctrine of Elements | Transcendental Doctrine of Method | ||||||||||||||

| First Part: Transcendental Aesthetic | Second Part: Transcendental Logic | Discipline of Pure Reason | Canon of Pure Reason | Architectonic of Pure Reason | History of Pure Reason | ||||||||||

| Space | Time | First Division: Transcendental Analytic | Second Division: Transcendental Dialectic | ||||||||||||

| Book I: Analytic of Concepts | Book II: Analytic of Principles | Transcendental Illusion | Pure Reason as the Seat of Transcendental Illusion | ||||||||||||

| Clue to the discovery of all pure concepts of the understanding | Deductions of the pure concepts of the understanding | Schematism | System of all principles | Phenomena and Noumena | Book I: Concept of Pure Reason | Book II: Dialectical Inferences of Pure Reason | |||||||||

| Paralogisms (Psychology) | Antinomies (Cosmology) | The Ideal (Theology) | |||||||||||||

I. Transcendental Doctrine of Elements

[edit]Transcendental Aesthetic

[edit]The Transcendental Aesthetic, as the Critique notes, deals with "all principles of a priori sensibility."[21] As a further delimitation, it "constitutes the first part of the transcendental doctrine of elements, in contrast to that which contains the principles of pure thinking, and is named transcendental logic".[21] In it, what is aimed at is "pure intuition and the mere form of appearances, which is the only thing that sensibility can make available a priori."[22] It is thus an analytic of the a priori constitution of sensibility; through which "Objects are therefore given to us..., and it alone affords us intuitions."[23] This in itself is an explication of the "pure form of sensible intuitions in general [that] is to be encountered in the mind a priori."[24] Thus, pure form or intuition is the a priori "wherein all of the manifold of appearances is intuited in certain relations."[24] from this, "a science of all principles of a priori sensibility [is called] the transcendental aesthetic."[21] The above stems from the fact that "there are two stems of human cognition...namely sensibility and understanding."[25]

This division, as the critique notes, comes "closer to the language and the sense of the ancients, among whom the division of cognition into αισθητα και νοητα is very well known."[26] An exposition on a priori intuitions is an analysis of the intentional constitution of sensibility. Since this lies a priori in the mind prior to actual object relation; "The transcendental doctrine of the senses will have to belong to the first part of the science of elements, since the conditions under which alone the objects of human cognition are given precede those under which those objects are thought".[27]

Kant distinguishes between the matter and the form of appearances. The matter is "that in the appearance that corresponds to sensation" (A20/B34). The form is "that which so determines the manifold of appearance that it allows of being ordered in certain relations" (A20/B34). Kant's revolutionary claim is that the form of appearances—which he later identifies as space and time—is a contribution made by the faculty of sensation to cognition, rather than something that exists independently of the mind. This is the thrust of Kant's doctrine of the transcendental ideality of space and time.

Kant's arguments for this conclusion are widely debated among Kant scholars. Some see the argument as based on Kant's conclusions that our representation (Vorstellung) of space and time is an a priori intuition. From here Kant is thought to argue that our representation of space and time as a priori intuitions entails that space and time are transcendentally ideal. It is undeniable from Kant's point of view that in Transcendental Philosophy, the difference of things as they appear and things as they are is a major philosophical discovery.[28] Others see the argument as based upon the question of whether synthetic a priori judgments are possible. Kant is taken to argue that the only way synthetic a priori judgments, such as those made in geometry, are possible is if space is transcendentally ideal.

In Section I (Of Space) of Transcendental Aesthetic in the Critique of Pure Reason Kant poses the following questions: What then are time and space? Are they real existences? Or, are they merely relations or determinations of things, such, however, as would equally belong to these things in themselves, though they should never become objects of intuition; or, are they such as belong only to the form of intuition, and consequently to the subjective constitution of the mind, without which these predicates of time and space could not be attached to any object?[29] The answer that space and time are real existences belongs to Newton. The answer that space and time are relations or determinations of things even when they are not being sensed belongs to Leibniz. Both answers maintain that space and time exist independently of the subject's awareness. This is exactly what Kant denies in his answer that space and time belong to the subjective constitution of the mind.[30]: 87–88

Space and time

[edit]Kant gives two expositions of space and time: metaphysical and transcendental. The metaphysical expositions of space and time are concerned with clarifying how those intuitions are known independently of experience. The transcendental expositions purport to show how the metaphysical conclusions give insight into the possibility of already obtained a priori scientific knowledge (A25/B40).

In the transcendental exposition, Kant refers back to his metaphysical exposition in order to show that the sciences would be impossible if space and time were not kinds of pure a priori intuitions. He asks the reader to take the proposition, "two straight lines can neither contain any space nor, consequently, form a figure," and then to try to derive this proposition from the concepts of a straight line and the number two. He concludes that it is simply impossible (A47-48/B65). Thus, since this information cannot be obtained from analytic reasoning, it must be obtained through synthetic reasoning, i.e., a synthesis of concepts (in this case two and straightness) with the pure (a priori) intuition of space.

In this case, however, it was not experience that furnished the third term; otherwise, the necessary and universal character of geometry would be lost. Only space, which is a pure a priori form of intuition, can make this synthetic judgment, thus it must then be a priori. If geometry does not serve this pure a priori intuition, it is empirical, and would be an experimental science, but geometry does not proceed by measurements—it proceeds by demonstrations.

The other part of the Transcendental Aesthetic argues that time is a pure a priori intuition that renders mathematics possible. Time is not a concept, since otherwise it would merely conform to formal logical analysis (and therefore, to the principle of non-contradiction). However, time makes it possible to deviate from the principle of non-contradiction: indeed, it is possible to say that A and non-A are in the same spatial location if one considers them in different times, and a sufficient alteration between states were to occur (A32/B48). Time and space cannot thus be regarded as existing in themselves. They are a priori forms of sensible intuition.

The current interpretation of Kant states that the subject possesses the capacity to perceive spatial and temporal presentations a priori. The Kantian thesis claims that in order for the subject to have any experience at all, then it must be bounded by these forms of presentations (Vorstellung). Some scholars have offered this position as an example of psychological nativism, as a rebuke to some aspects of classical empiricism.[citation needed]

Kant's thesis concerning the transcendental ideality of space and time limits appearances to the forms of sensibility—indeed, they form the limits within which these appearances can count as sensible; and it necessarily implies that the thing-in-itself is neither limited by them nor can it take the form of an appearance within us apart from the bounds of sensibility (A48-49/B66). Yet the thing-in-itself is held by Kant to be the cause of that which appears, and this is where an apparent paradox of Kantian critique resides: while we are prohibited from knowledge of the thing-in-itself, we can attribute it as being something beyond ourselves as a causally responsible source of representations within us. Kant's view of space and time rejects both the space and time of Aristotelian physics and the space and time of Newtonian physics.

Transcendental Logic

[edit]

In the Transcendental Logic, there is a section (titled The Refutation of Idealism) that is intended to free Kant's doctrine from any vestiges of subjective idealism, which would either doubt or deny the existence of external objects (B274-79).[31] Kant's distinction between the appearance and the thing-in-itself is not intended to imply that nothing knowable exists apart from consciousness, as with subjective idealism. Rather, it declares that knowledge is limited to phenomena as objects of a sensible intuition. In the Fourth Paralogism ("... A Paralogism is a logical fallacy"),[32] Kant further certifies his philosophy as separate from that of subjective idealism by defining his position as a transcendental idealism in accord with empirical realism (A366–80), a form of direct realism.[33][a] "The Paralogisms of Pure Reason" is the only chapter of the Dialectic that Kant rewrote for the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason. In the first edition, the Fourth Paralogism offers a defence of transcendental idealism, which Kant reconsidered and relocated in the second edition.[36]

Whereas the Transcendental Aesthetic was concerned with the role of the sensibility, the Transcendental Logic is concerned with the role of the understanding, which Kant defines as the faculty of the mind that deals with concepts.[37] Knowledge, Kant argued, contains two components: intuitions, through which an object is given to us in sensibility, and concepts, through which an object is thought in understanding. In the Transcendental Aesthetic, he attempted to show that the a priori forms of intuition were space and time, and that these forms were the conditions of all possible intuition. It should therefore be expected that we should find similar a priori concepts in the understanding, and that these pure concepts should be the conditions of all possible thought. The Logic is divided into two parts: the Transcendental Analytic and the Transcendental Dialectic. The Analytic Kant calls a "logic of truth";[38] in it he aims to discover these pure concepts which are the conditions of all thought, and are thus what makes knowledge possible. The Transcendental Dialectic Kant calls a "logic of illusion";[39] in it he aims to expose the illusions that we create when we attempt to apply reason beyond the limits of experience.

The idea of a transcendental logic is that of a logic that gives an account of the origins of our knowledge as well as its relationship to objects. Kant contrasts this with the idea of a general logic, which abstracts from the conditions under which our knowledge is acquired, and from any relation that knowledge has to objects. According to Helge Svare, "It is important to keep in mind what Kant says here about logic in general, and transcendental logic in particular, being the product of abstraction, so that we are not misled when a few pages later he emphasizes the pure, non-empirical character of the transcendental concepts or the categories."[40]

Kant's investigations in the Transcendental Logic lead him to conclude that understanding and reason can only legitimately be applied to things as they appear phenomenally to us in experience. What things are in themselves as being noumenal, independent of our cognition, remains limited by what is known through phenomenal experience.

First Division: Transcendental Analytic

[edit]The Transcendental Analytic is divided into an Analytic of Concepts and an Analytic of Principles, as well as a third section concerned with the distinction between phenomena and noumena. In Chapter III (Of the ground of the division of all objects into phenomena and noumena) of the Transcendental Analytic, Kant generalizes the implications of the Analytic in regard to transcendent objects preparing the way for the explanation in the Transcendental Dialectic about thoughts of transcendent objects, Kant's detailed theory of the content (Inhalt) and origin of our thoughts about specific transcendent objects.[30]: 198–199 The main sections of the Analytic of Concepts are The Metaphysical Deduction and The Transcendental Deduction of the Categories. The main sections of the Analytic of Principles are the Schematism, Axioms of Intuition, Anticipations of Perception, Analogies of Experience, Postulates and follow the same recurring tabular form:

| 1. Quantity | ||

| 2. Quality |

3. Relation | |

| 4. Modality |

In the 2nd edition, these sections are followed by a section titled the Refutation of Idealism.

The metaphysical deduction

[edit]In the Metaphysical Deduction, Kant aims to derive twelve pure concepts of the understanding (which he calls "categories") from the logical forms of judgment. In the following section, he will go on to argue that these categories are conditions of all thought in general. Kant arranges the forms of judgment in a table of judgments, which he uses to guide the derivation of the table of categories.[41]

The role of the understanding is to make judgments. In judgment, the understanding employs concepts which apply to the intuitions given to us in sensibility. Judgments can take different logical forms, with each form combining concepts in different ways. Kant claims that if we can identify all of the possible logical forms of judgment, this will serve as a "clue" to the discovery of the most basic and general concepts that are employed in making such judgments, and thus that are employed in all thought.[41]

Logicians prior to Kant had concerned themselves to classify the various possible logical forms of judgment. Kant, with only minor modifications, accepts and adopts their work as correct and complete, and lays out all the logical forms of judgment in a table, reduced under four heads:

| 1. Quantity of Judgments | ||

| 2. Quality |

3. Relation | |

| 4. Modality |

Under each head, there corresponds three logical forms of judgment:[42]

1. Quantity of Judgments

|

||

2. Quality

|

3. Relation

| |

4. Modality

|

This Aristotelian method for classifying judgments is the basis for his own twelve corresponding concepts of the understanding. In deriving these concepts, he reasons roughly as follows. If we are to possess pure concepts of the understanding, they must relate to the logical forms of judgment. However, if these pure concepts are to be applied to intuition, they must have content. But the logical forms of judgment are by themselves abstract and contentless. Therefore, to determine the pure concepts of the understanding we must identify concepts which both correspond to the logical forms of judgment, and are able to play a role in organising intuition. Kant therefore attempts to extract from each of the logical forms of judgment a concept which relates to intuition. For example, corresponding to the logical form of hypothetical judgment ('If p, then q'), there corresponds the category of causality ('If one event, then another'). Kant calls these pure concepts 'categories', echoing the Aristotelian notion of a category as a concept which is not derived from any more general concept. He follows a similar method for the other eleven categories, then represents them in the following table:[43]

1. Categories of Quantity

|

||

2. Categories of Quality

|

3. Categories of Relation

| |

4. Categories of Modality

|

These categories, then, are the fundamental, primary, or native concepts of the understanding. These flow from, or constitute the mechanism of understanding and its nature, and are inseparable from its activity. Therefore, for human thought, they are universal and necessary, or a priori. As categories they are not contingent states or images of sensuous consciousness, and hence not to be thence derived. Similarly, they are not known to us independently of such consciousness or of sensible experience. On the one hand, they are exclusively involved in, and hence come to our knowledge exclusively through, the spontaneous activity of the understanding. This understanding is never active, however, until sensible data are furnished as material for it to act upon, and so it may truly be said that they become known to us "only on the occasion of sensible experience". For Kant, in opposition to Christian Wolff and Thomas Hobbes, the categories exist only in the mind.[44]

These categories are "pure" conceptions of the understanding, in as much as they are independent of all that is contingent in sense. They are not derived from what is called the matter of sense, or from particular, variable sensations. However, they are not independent of the universal and necessary form of sense. Again, Kant, in the "Transcendental Logic", is professedly engaged with the search for an answer to the second main question of the Critique: How is pure physical science, or sensible knowledge, possible? Kant, now, has said, and, with reference to the kind of knowledge mentioned in the foregoing question, has said truly, that thoughts, without the content which perception supplies, are empty. This is not less true of pure thoughts, than of any others. The content which the pure conceptions, as categories of pure physical science or sensible knowledge, cannot derive from the matter of sense, they must and do derive from its pure form. And in this relation between the pure conceptions of the understanding and their pure content there is involved, as we shall see, the most intimate community of nature and origin between sense, on its formal side (space and time), and the understanding itself. For Kant, space and time are a priori intuitions. Out of a total of six arguments in favor of space as a priori intuition, Kant presents four of them in the Metaphysical Exposition of space: two argue for space a priori and two for space as intuition.[30]: 75

The transcendental deduction

[edit]In the Transcendental Deduction, Kant aims to show that the categories derived in the Metaphysical Deduction are conditions of all possible experience. He achieves this proof roughly by the following line of thought: all representations must have some common ground if they are to be the source of possible knowledge (because extracting knowledge from experience requires the ability to compare and contrast representations that may occur at different times or in different places). This ground of all experience is the self-consciousness of the experiencing subject, and the constitution of the subject is such that all thought is rule-governed in accordance with the categories. It follows that the categories feature as necessary components in any possible experience.[45]

| 1.Axioms of intuition | ||

| 2.Anticipations of perception |

3.Analogies of experience | |

| 4.Postulates of empirical thought in general |

The schematism

[edit]In order for any concept to have meaning, it must be related to sense perception. The 12 categories, or a priori concepts, are related to phenomenal appearances through schemata. Each category has a schema. It is a connection through time between the category, which is an a priori concept of the understanding, and a phenomenal a posteriori appearance. These schemata are needed to link the pure category to sensed phenomenal appearances because the categories are, as Kant says, heterogeneous with sense intuition. Categories and sensed phenomena, however, do share one characteristic: time. Succession is the form of sense impressions and also of the Category of causality. Therefore, time can be said to be the schema of Categories or pure concepts of the understanding.[46]

The refutation of idealism

[edit]In order to answer criticisms of the Critique of Pure Reason that Transcendental Idealism denied the reality of external objects, Kant added a section to the second edition (1787) titled "The Refutation of Idealism" which turns the "game" of idealism against itself by arguing that self-consciousness presupposes external objects. Defining self-consciousness as a determination of the self in time, Kant argues that all determinations of time presuppose something permanent in perception and that this permanence cannot be in the self, since it is only through the permanence that one's existence in time can itself be determined. This argument inverted the supposed priority of inner over outer experience that had dominated philosophies of mind and knowledge since René Descartes. In Book II, chapter II, section III of the Transcendental Analytic, right under "The Postulates of Empirical Thought", Kant adds a "Refutation of Idealism (Widerlegung des Idealismus)", where he refutes both Descartes' problematic idealism and Berkeley's dogmatic idealism. According to Kant, in problematic idealism the existence of objects is doubtful or impossible to prove, while in dogmatic idealism the existence of space and therefore of spatial objects is impossible. In contradistinction, Kant holds that external objects may be directly perceived and that such experience is a necessary presupposition of self-consciousness.[47]

Appendix: "Amphiboly of Concepts of Reflection"

[edit]As an Appendix to the First Division of Transcendental Logic, Kant intends the "Amphiboly of the Conceptions of Reflection" to be a critique of Leibniz's metaphysics and a prelude to Transcendental Dialectic, the Second Division of Transcendental Logic. Kant introduces a whole set of new ideas called "concepts of reflection": identity/difference, agreement/opposition, inner/outer and matter/form. According to Kant, the categories do have but these concepts have no synthetic function in experience. These special concepts just help to make comparisons between concepts judging them either different or the same, compatible or incompatible. It is this particular action of making a judgment that Kant calls "logical reflection."[30]: 206 As Kant states: "Through observation and analysis of appearances we penetrate to nature's inner recesses, and no one can say how far this knowledge may in time extend. But with all this knowledge, and even if the whole of nature were revealed to us, we should still never be able to answer those transcendental questions which go beyond nature. The reason of this is that it is not given to us to observe our own mind with any other intuition than that of inner sense; and that it is yet precisely in the mind that the secret of the source of our sensibility is located. The relation of sensibility to an object and what the transcendental ground of this [objective] unity may be, are matters undoubtedly so deeply concealed that we, who after all know even ourselves only through inner sense and therefore as appearance, can never be justified in treating sensibility as being a suitable instrument of investigation for discovering anything save always still other appearances – eager as we yet are to explore their non-sensible cause." (A278/B334)

Second Division: Transcendental Dialectic

[edit]Following the systematic treatment of a priori knowledge given in the transcendental analytic, the transcendental dialectic seeks to dissect dialectical illusions. Its task is effectively to expose the fraudulence of the non-empirical employment of the understanding. The Transcendental Dialectic shows how pure reason should not be used. According to Kant, the rational faculty is plagued with dialectic illusions as man attempts to know what can never be known.[48]

This longer but less dense section of the Critique is composed of five essential elements, including an Appendix, as follows: (a) Introduction (to Reason and the Transcendental Ideas), (b) Rational Psychology (the nature of the soul), (c) Rational Cosmology (the nature of the world), (d) Rational Theology (God), and (e) Appendix (on the constitutive and regulative uses of reason).

In the introduction, Kant introduces a new faculty, human reason, positing that it is a unifying faculty that unifies the manifold of knowledge gained by the understanding. Another way of thinking of reason is to say that it searches for the 'unconditioned'; Kant had shown in the Second Analogy that every empirical event has a cause, and thus each event is conditioned by something antecedent to it, which itself has its own condition, and so forth. Reason seeks to find an intellectual resting place that may bring the series of empirical conditions to a close, to obtain knowledge of an 'absolute totality' of conditions, thus becoming unconditioned. All in all, Kant ascribes to reason the faculty to understand and at the same time criticize the illusions it is subject to.[49][verification needed]

The paralogisms of pure reason

[edit]One of the ways that pure reason erroneously tries to operate beyond the limits of possible experience is when it thinks that there is an immortal Soul in every person. Its proofs, however, are paralogisms, or the results of false reasoning.

The soul is substance

[edit]Every one of my thoughts and judgments is based on the presupposition "I think". "I" is the subject and thinking is the predicate. Yet the ever-present logical subject of every thought should not be confused with a permanent, immortal, real substance (soul). The logical subject is a mere idea, not a real substance. Unlike Descartes, who believes that the soul may be known directly through reason, Kant asserts that no such thing is possible. Descartes declares cogito ergo sum, but Kant denies that any knowledge of "I" may be possible. "I" is only the background of the field of apperception and as such lacks the experience of direct intuition that would make self-knowledge possible. This implies that the self in itself could never be known. Like Hume, Kant rejects knowledge of the "I" as substance. For Kant, the "I" that is taken to be the soul is purely logical and involves no intuitions. The "I" is the result of the a priori consciousness continuum, not of direct intuition a posteriori. It is apperception as the principle of unity in the consciousness continuum that dictates the presence of "I" as a singular logical subject of all the representations of a single consciousness. Although "I" seems to refer to the same "I" all the time, it is not really a permanent feature but only the logical characteristic of a unified consciousness.[50]

The soul is simple

[edit]The only use or advantage of asserting that the soul is simple is to differentiate it from matter and therefore prove that it is immortal, but the substratum of matter may also be simple. Since we know nothing of this substratum, both matter and soul may be fundamentally simple and therefore not different from each other. Then the soul may decay, as does matter. It makes no difference to say that the soul is simple and therefore immortal. Such a simple nature can never be known through experience. It has no objective validity. According to Descartes, the soul is indivisible. This paralogism mistakes the unity of apperception for the unity of an indivisible substance called the soul. It is a mistake that is the result of the first paralogism. It is impossible that thinking (Denken) could be composite for if the thought by a single consciousness were to be distributed piecemeal among different consciousnesses, the thought would be lost. According to Kant, the most important part of this proposition is that a multi-faceted presentation requires a single subject. This paralogism misinterprets the metaphysical oneness of the subject by interpreting the unity of apperception as being indivisible and the soul simple as a result. According to Kant, the simplicity of the soul as Descartes believed cannot be inferred from the "I think" as it is assumed to be there in the first place. Therefore, it is a tautology.[51]

The soul is a person

[edit]In order to have coherent thoughts, I must have an "I" that is not changing and that thinks the changing thoughts. Yet we cannot prove that there is a permanent soul or an undying "I" that constitutes my person. I only know that I am one person during the time that I am conscious. As a subject who observes my own experiences, I attribute a certain identity to myself, but, to another observing subject, I am an object of his experience. He may attribute a different persisting identity to me. In the third paralogism, the "I" is a self-conscious person in a time continuum, which is the same as saying that personal identity is the result of an immaterial soul. The third paralogism mistakes the "I", as unit of apperception being the same all the time, with the everlasting soul. According to Kant, the thought of "I" accompanies every personal thought and it is this that gives the illusion of a permanent I. However, the permanence of "I" in the unity of apperception is not the permanence of substance. For Kant, permanence is a schema, the conceptual means of bringing intuitions under a category. The paralogism confuses the permanence of an object seen from without with the permanence of the "I" in a unity of apperception seen from within. From the oneness of the apperceptive "I" nothing may be deduced. The "I" itself shall always remain unknown. The only ground for knowledge is the intuition, the basis of sense experience.[52]

The soul is separated from the experienced world

[edit]The soul is not separate from the world. They exist for us only in relation to each other. Whatever we know about the external world is only a direct, immediate, internal experience. The world appears, in the way that it appears, as a mental phenomenon. We cannot know the world as a thing-in-itself, that is, other than as an appearance within us. To think about the world as being totally separate from the soul is to think that a mere phenomenal appearance has independent existence outside of us. If we try to know an object as being other than an appearance, it can only be known as a phenomenal appearance, never otherwise. We cannot know a separate, thinking, non-material soul or a separate, non-thinking, material world because we cannot know things, as to what they may be by themselves, beyond being objects of our senses. The fourth paralogism is passed over lightly or not treated at all by commentators. In the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, the fourth paralogism is addressed to refuting the thesis that there is no certainty of the existence of the external world. In the second edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, the task at hand becomes the Refutation of Idealism. Sometimes, the fourth paralogism is taken as one of the most awkward of Kant's invented tetrads. Nevertheless, in the fourth paralogism, there is a great deal of philosophizing about the self that goes beyond the mere refutation of idealism. In both editions, Kant is trying to refute the same argument for the non-identity of mind and body.[53] In the first edition, Kant refutes the Cartesian doctrine that there is direct knowledge of inner states only and that knowledge of the external world is exclusively by inference. Kant claims mysticism is one of the characteristics of Platonism, the main source of dogmatic idealism. Kant explains skeptical idealism by developing a syllogism called "The Fourth Paralogism of the Ideality of Outer Relation:"

- That whose existence can be inferred only as a cause of given perceptions has only a doubtful existence.

- And the existence of outer appearances cannot be immediately perceived but can be inferred only as the cause of given perceptions.

- Then, the existence of all objects of outer sense is doubtful.[54]

Kant may have had in mind an argument by Descartes:

- My own existence is not doubtful

- But the existence of physical things is doubtful

- Therefore, I am not a physical thing.

It is questionable that the fourth paralogism should appear in a chapter on the soul. What Kant implies about Descartes' argument in favor of the immaterial soul is that the argument rests upon a mistake on the nature of objective judgment not on any misconceptions about the soul. The attack is mislocated.[55]

These Paralogisms cannot be proven for speculative reason and therefore can give no certain knowledge about the Soul. However, they can be retained as a guide to human behavior. In this way, they are necessary and sufficient for practical purposes. In order for humans to behave properly, they can suppose that the soul is an imperishable substance, it is indestructibly simple, it stays the same forever, and it is separate from the decaying material world. On the other hand, anti-rationalist critics of Kant's ethics consider it too abstract, alienating, altruistic or detached from human concern to actually be able to guide human behavior. It is then that the Critique of Pure Reason offers the best defense, demonstrating that in human concern and behavior, the influence of rationality is preponderant.[56]

The antinomy of pure reason

[edit]Kant presents the four antinomies of reason in the Critique of Pure Reason as going beyond the rational intention of reaching a conclusion. For Kant, an antinomy is a pair of faultless arguments in favor of opposite conclusions. Historically, Leibniz and Samuel Clarke (Newton's spokesman) had just recently engaged in a titanic debate of unprecedented repercussions. Kant's formulation of the arguments was affected accordingly.[57]

The Ideas of Rational Cosmology are dialectical. They result in four kinds of opposing assertions, each of which is logically valid. The antinomy, with its resolution, is as follows:

- Thesis: The world has, as to time and space, a beginning (limit).

- Antithesis: The world is, as to time and space, infinite.

- Both are false. The world is an object of experience. Neither statement is based on experience.

- Thesis: Everything in the world consists of elements that are simple.

- Antithesis: There is no simple thing, but everything is composite.

- Both are false. Things are objects of experience. Neither statement is based on experience.

- Thesis: There are in the world causes through freedom.

- Antithesis: There is no freedom, but all is nature.

- Both may be true. The thesis may be true of things-in-themselves (other than as they appear). The antithesis may be true of things as they appear.

- Thesis: In the series of the world-causes there is some necessary being.

- Antithesis: There is nothing necessary in the world, but in this series all is contingent.

- Both may be true. The thesis may be true of things-in-themselves (other than as they appear). The antithesis may be true of things as they appear.

According to Kant, rationalism came to fruition by defending the thesis of each antinomy while empiricism evolved into new developments by working to better the arguments in favor of each antithesis.[58]

The ideal of pure reason

[edit]Pure reason mistakenly goes beyond its relation to possible experience when it concludes that there is a Being who is the most real thing (ens realissimum) conceivable. This ens realissimum is the philosophical origin of the idea of God. This personified object is postulated by Reason as the subject of all predicates, the sum total of all reality. Kant called this Supreme Being, or God, the Ideal of Pure Reason because it exists as the highest and most complete condition of the possibility of all objects, their original cause and their continual support.[59]

Refutation of the ontological proof of God's existence of Anselm of Canterbury

[edit]The ontological proof can be traced back to Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109). Anselm presented the proof in chapter II of a short treatise titled "Discourse on the existence of God." It was not Kant but the monk Gaunilo and later the Scholastic Thomas Aquinas who first challenged the success of the proof. Aquinas went on to provide his own proofs for the existence of God in what are known as the Five Ways.[60]

The ontological proof considers the concept of the most real Being (ens realissimum) and concludes that it is necessary. The ontological argument states that God exists because he is perfect. If he did not exist, he would be less than perfect. Existence is assumed to be a predicate or attribute of the subject, God, but Kant asserted that existence is not a predicate. Existence or Being is merely the infinitive of the copula or linking, connecting verb "is" in a declarative sentence. It connects the subject to a predicate. "Existence is evidently not a real predicate ... The small word is, is not an additional predicate, but only serves to put the predicate in relation to the subject." (A599) Also, we cannot accept a mere concept or mental idea as being a real, external thing or object. The Ontological Argument starts with a mere mental concept of a perfect God and tries to end with a real, existing God.

The argument is essentially deductive in nature. Given a certain fact, it proceeds to infer another from it. The method pursued, then, is that of deducing the fact of God's being from the a priori idea of him. If man finds that the idea of God is necessarily involved in his self-consciousness, it is legitimate for him to proceed from this notion to the actual existence of the divine being. In other words, the idea of God necessarily includes existence. It may include it in several ways. One may argue, for instance, according to the method of Descartes, and say that the conception of God could have originated only with the divine being himself, therefore the idea possessed by us is based on the prior existence of God himself. Or we may allege that we have the idea that God is the most necessary of all beings—that is to say, he belongs to the class of realities; consequently it cannot but be a fact that he exists. This is held to be proof per saltum. A leap takes place from the premise to the conclusion, and all intermediate steps are omitted.

The implication is that premise and conclusion stand over against one another without any obvious, much less necessary, connection. A jump is made from thought to reality. Kant here objects that being or existence is not a mere attribute that may be added onto a subject, thereby increasing its qualitative content. The predicate, being, adds something to the subject that no mere quality can give. It informs us that the idea is not a mere conception, but is also an actually existing reality. Being, as Kant thinks, actually increases the concept itself in such a way as to transform it. You may attach as many attributes as you please to a concept; you do not thereby lift it out of the subjective sphere and render it actual. So you may pile attribute upon attribute on the conception of God, but at the end of the day you are not necessarily one step nearer his actual existence. So that when we say God exists, we do not simply attach a new attribute to our conception; we do far more than this implies. We pass our bare concept from the sphere of inner subjectivity to that of actuality. This is the great vice of the Ontological argument. The idea of ten dollars is different from the fact only in reality. In the same way the conception of God is different from the fact of his existence only in reality. When, accordingly, the Ontological proof declares that the latter is involved in the former, it puts forward nothing more than a mere statement. No proof is forthcoming precisely where proof is most required. We are not in a position to say that the idea of God includes existence, because it is of the very nature of ideas not to include existence.

Kant explains that, being, not being a predicate, could not characterize a thing. Logically, it is the copula of a judgment. In the proposition, "God is almighty", the copula "is" does not add a new predicate; it only unites a predicate to a subject. To take God with all its predicates and say that "God is" is equivalent to "God exists" or that "There is a God" is to jump to a conclusion as no new predicate is being attached to God. The content of both subject and predicate is one and the same. According to Kant then, existence is not really a predicate. Therefore, there is really no connection between the idea of God and God's appearance or disappearance. No statement about God whatsoever may establish God's existence. Kant makes a distinction between "in intellectus" (in mind) and "in re" (in reality or in fact) so that questions of being are a priori and questions of existence are resolved a posteriori.[61]

Refutation of the cosmological ("prime mover") proof of God's existence

[edit]The cosmological proof considers the concept of an absolutely necessary Being and concludes that it has the most reality. In this way, the cosmological proof is merely the converse of the ontological proof. Yet the cosmological proof purports to start from sense experience. It says, "If anything exists in the cosmos, then there must be an absolutely necessary Being. " It then claims, on Kant's interpretation, that there is only one concept of an absolutely necessary object. That is the concept of a Supreme Being who has maximum reality. Only such a supremely real being would be necessary and independently existent, but, according to Kant, this is the Ontological Proof again, which was asserted a priori without sense experience.

Summarizing the cosmological argument further, it may be stated as follows: "Contingent things exist—at least I exist; and as they are not self-caused, nor capable of explanation as an infinite series, it is requisite to infer that a necessary being, on whom they depend, exists." Seeing that this being exists, he belongs to the realm of reality. Seeing that all things issue from him, he is the most necessary of beings, for only a being who is self-dependent, who possesses all the conditions of reality within himself, could be the origin of contingent things. And such a being is God.

Kant argues that this proof is invalid for three chief reasons. First, it makes use of a category, namely, Cause. And, as has been already pointed out, it is not possible to apply this, or any other, category except to the matter given by sense under the general conditions of space and time. If, then, we employ it in relation to Deity, we try to force its application in a sphere where it is useless, and incapable of affording any information. Once more, we are in the now familiar difficulty of the paralogism of Rational Psychology or of the Antinomies. The category has meaning only when applied to phenomena. Yet God is a noumenon. Second, it mistakes an idea of absolute necessity—an idea that is nothing more than an ideal—for a synthesis of elements in the phenomenal world or world of experience. This necessity is not an object of knowledge, derived from sensation and set in shape by the operation of categories. It cannot be regarded as more than an inference. Yet the cosmological argument treats it as if it were an object of knowledge exactly on the same level as perception of any thing or object in the course of experience. Thirdly, according to Kant, it presupposes the Ontological argument, already proved false. It does this, because it proceeds from the conception of the necessity of a certain being to the fact of his existence. Yet it is possible to take this course only if idea and fact are convertible with one another, and it has just been proved that they are not so convertible.[62]

Physico-theological ("watch maker") proof of God's existence

[edit]The physico-theological proof of God's existence is supposed to be based on a posteriori sensed experience of nature and not on mere a priori abstract concepts. It observes that the objects in the world have been intentionally arranged with great wisdom. The fitness of this arrangement could never have occurred randomly, without purpose. The world must have been caused by an intelligent power. The unity of the relation between all of the parts of the world leads us to infer that there is only one cause of everything. That one cause is a perfect, mighty, wise, and self-sufficient Being. This physico-theology does not, however, prove with certainty the existence of God. For this, we need something absolutely necessary that consequently has all-embracing reality, but this is the Cosmological Proof, which concludes that an all-encompassing real Being has absolutely necessary existence. All three proofs can be reduced to the Ontological Proof, which tried to make an objective reality out of a subjective concept.

In abandoning any attempt to prove the existence of God, Kant declares the three proofs of rational theology known as the ontological, the cosmological and the physico-theological as quite untenable.[63] However, it is important to realize that while Kant intended to refute various purported proofs of the existence of God, he also intended to demonstrate the impossibility of proving the non-existence of God. Far from advocating for a rejection of religious belief, Kant rather hoped to demonstrate the impossibility of attaining the sort of substantive metaphysical knowledge (either proof or disproof) about God, free will, or the soul that many previous philosophers had pursued.

II. Transcendental Doctrine of Method

[edit]The second book in the Critique, and by far the shorter of the two, attempts to lay out the formal conditions of the complete system of pure reason.

In the Transcendental Dialectic, Kant showed how pure reason is improperly used when it is not related to experience. In the Method of Transcendentalism, he explained the proper use of pure reason.

The discipline of pure reason

[edit]In section I, the discipline of pure reason in the sphere of dogmatism, of chapter I, the discipline of pure reason, of Part II, transcendental discipline of method, of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant enters into the most extensive discussion of the relationship between mathematical theory and philosophy.[64]

Discipline is the restraint, through caution and self-examination, that prevents philosophical pure reason from applying itself beyond the limits of possible sensual experience. Philosophy cannot possess dogmatic certainty. Philosophy, unlike mathematics, cannot have definitions, axioms or demonstrations. All philosophical concepts must be ultimately based on a posteriori, experienced intuition. This is different from algebra and geometry, which use concepts that are derived from a priori intuitions, such as symbolic equations and spatial figures. Kant's basic intention in this section of the text is to describe why reason should not go beyond its already well-established limits. In section I, the discipline of pure reason in the sphere of dogmatism, Kant clearly explains why philosophy cannot do what mathematics can do in spite of their similarities. Kant also explains that when reason goes beyond its own limits, it becomes dogmatic. For Kant, the limits of reason lie in the field of experience as, after all, all knowledge depends on experience. According to Kant, a dogmatic statement would be a statement that reason accepts as true even though it goes beyond the bounds of experience.[65]

Restraint should be exercised in the polemical use of pure reason. Kant defined this polemical use as the defense against dogmatic negations. For example, if it is dogmatically affirmed that God exists or that the soul is immortal, a dogmatic negation could be made that God does not exist or that the soul is not immortal. Such dogmatic assertions cannot be proved. The statements are not based on possible experience. In section II, the discipline of pure reason in polemics, Kant argues strongly against the polemical use of pure reason. The dogmatic use of reason would be the acceptance as true of a statement that goes beyond the bounds of reason while the polemic use of reason would be the defense of such statement against any attack that could be raised against it. For Kant, then, there cannot possibly be any polemic use of pure reason. Kant argues against the polemic use of pure reason and considers it improper on the grounds that opponents cannot engage in a rational dispute based on a question that goes beyond the bounds of experience.[65]

Kant claimed that adversaries should be freely allowed to speak reason. In return, they should be opposed through reason. Dialectical strife leads to an increase of reason's knowledge. Yet there should be no dogmatic polemical use of reason. The critique of pure reason is the tribunal for all of reason's disputes. It determines the rights of reason in general. We should be able to openly express our thoughts and doubts. This leads to improved insight. We should eliminate polemic in the form of opposed dogmatic assertions that cannot be related to possible experience.

According to Kant, the censorship of reason is the examination and possible rebuke of reason. Such censorship leads to doubt and skepticism. After dogmatism produces opposing assertions, skepticism usually occurs. The doubts of skepticism awaken reason from its dogmatism and bring about an examination of reason's rights and limits. It is necessary to take the next step after dogmatism and skepticism. This is the step to criticism. By criticism, the limits of our knowledge are proved from principles, not from mere personal experience.

If criticism of reason teaches us that we cannot know anything unrelated to experience, can we have hypotheses, guesses, or opinions about such matters? We can only imagine a thing that would be a possible object of experience. The hypotheses of God or a soul cannot be dogmatically affirmed or denied, but we have a practical interest in their existence. It is therefore up to an opponent to prove that they do not exist. Such hypotheses can be used to expose the pretensions of dogmatism. Kant explicitly praises Hume on his critique of religion for being beyond the field of natural science. However, Kant goes so far and not further in praising Hume basically because of Hume's skepticism. If only Hume would be critical rather than skeptical, Kant would be all-praises. In concluding that there is no polemical use of pure reason, Kant also concludes there is no skeptical use of pure reason. In section II, the discipline of pure reason in polemics, in a special section, skepticism not a permanent state for human reason, Kant mentions Hume but denies the possibility that skepticism could possibly be the final end of reason or could possibly serve its best interests.[66]

Proofs of transcendental propositions about pure reason (God, soul, free will, causality, simplicity) must first prove whether the concept is valid. Reason should be moderated and not asked to perform beyond its power. The three rules of the proofs of pure reason are: (1) consider the legitimacy of your principles, (2) each proposition can have only one proof because it is based on one concept and its general object, and (3) only direct proofs can be used, never indirect proofs (e.g., a proposition is true because its opposite is false). By attempting to directly prove transcendental assertions, it will become clear that pure reason can gain no speculative knowledge and must restrict itself to practical, moral principles. The dogmatic use of reason is called into question by the skeptical use of reason but skepticism does not present a permanent state for human reason. Kant proposes instead a critique of pure reason by means of which the limitations of reason are clearly established and the field of knowledge is circumscribed by experience. According to the rationalists and skeptics, there are analytic judgments a priori and synthetic judgments a posteriori. Analytic judgments a posteriori do not really exist. Added to all these rational judgments is Kant's great discovery of the synthetic judgment a priori.[67]

The canon of pure reason

[edit]The canon of pure reason is a discipline for the limitation of pure reason. The analytic part of logic in general is a canon for the understanding and reason in general. However, the Transcendental Analytic is a canon of the pure understanding for only the pure understanding is able to judge synthetically a priori.[68]

The speculative propositions of God, immortal soul, and free will have no cognitive use but are valuable to our moral interest. In pure philosophy, reason is morally (practically) concerned with what ought to be done if the will is free, if there is a God, and if there is a future world. Yet, in its actual practical employment and use, reason is only concerned with the existence of God and a future life. Basically, the canon of pure reason deals with two questions: Is there a God? Is there a future life? These questions are translated by the canon of pure reason into two criteria: What ought I to do? and What may I hope for? yielding the postulates of God's own existence and a future life, or life in the future.[69]

The greatest advantage of the philosophy of pure reason is negative, the prevention of error. Yet moral reason can provide positive knowledge. There cannot be a canon, or system of a priori principles, for the correct use of speculative reason. However, there can be a canon for the practical (moral) use of reason.

Reason has three main questions and answers:

- What can I know? We cannot know, through reason, anything that cannot be a possible sense experience; ("that all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt")

- What should I do? Do that which will make you deserve happiness;

- What may I hope? We can hope to be happy as far as we have made ourselves deserving of it through our conduct.

Reason tells us that there is a God, the supreme good, who arranges a future life in a moral world. If not, moral laws would be idle fantasies. Our happiness in that intelligible world will exactly depend on how we have made ourselves worthy of being happy. The union of speculative and practical reason occurs when we see God's reason and purpose in nature's unity of design or general system of ends. The speculative extension of reason is severely limited in the transcendental dialectics of the Critique of Pure Reason, which Kant would later fully explore in the Critique of Practical Reason.[70]

In the transcendental use of reason, there can be neither opinion nor knowledge. Reason results in a strong belief in the unity of design and purpose in nature. This unity requires a wise God who provides a future life for the human soul. Such a strong belief rests on moral certainty, not logical certainty. Even if a person has no moral beliefs, the fear of God and a future life acts as a deterrent to evil acts, because no one can prove the non-existence of God and an afterlife. Does all of this philosophy merely lead to two articles of faith, namely, God and the immortal soul? With regard to these essential interests of human nature, the highest philosophy can achieve no more than the guidance, which belongs to the pure understanding. Some would even go so far as to interpret the Transcendental Analytic of the Critique of Pure Reason as a return to the Cartesian epistemological tradition and a search for truth through certainty.[71]

The architectonic of pure reason

[edit]All knowledge from pure reason is architectonic in that it is a systematic unity. The entire system of metaphysic consists of: (1.) Ontology—objects in general; (2.) Rational Physiology—given objects; (3.) Rational cosmology—the whole world; (4.) Rational Theology—God. Metaphysic supports religion and curbs the extravagant use of reason beyond possible experience. The components of metaphysic are criticism, metaphysic of nature, and metaphysic of morals. These constitute philosophy in the genuine sense of the word. It uses science to gain wisdom. Metaphysic investigates reason, which is the foundation of science. Its censorship of reason promotes order and harmony in science and maintains metaphysic's main purpose, which is general happiness. In chapter III, the architectonic of pure reason, Kant defines metaphysics as the critique of pure reason in relation to pure a priori knowledge. Morals, analytics and dialectics for Kant constitute metaphysics, which is philosophy and the highest achievement of human reason.[72]

The history of pure reason

[edit]Kant writes that metaphysics began with the study of the belief in God and the nature of a future world, beyond this immediate world as we know it, in our common sense. It was concluded early that good conduct would result in happiness in another world as arranged by God. The object of rational knowledge was investigated by sensualists (Epicurus), and intellectualists (Plato). Sensualists claimed that only the objects of the senses are real. Intellectualists asserted that true objects are known only by the understanding mind. Aristotle and Locke thought that the pure concepts of reason are derived only from experience. Plato and Leibniz contended that they come from reason, not sense experience, which is illusory. Epicurus never speculated beyond the limits of experience. Locke, however, said that the existence of God and the immortality of the soul could be proven. Those who follow the naturalistic method of studying the problems of pure reason use their common, sound, or healthy reason, not scientific speculation. Others, who use the scientific method, are either dogmatists (Wolff) or skeptics (Hume). In Kant's view, all of the above methods are faulty. The method of criticism remains as the path toward the completely satisfying answers to the metaphysical questions about God and the future life in another world.

Terms and phrases